Abstract

The TBS is a new method for clinicians to assess the bone quality. It is directly related to the mechanical strength of bone and helps predict fracture risk. The present analysis aimed to investigate the associations between serum PTH levels and TBS by analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). A total of 3516 participants from the NHANES 2005–2006 were included in this cross-sectional study. The independent variable was serum PTH, and the outcome variable was TBS. The associations of serum PTH levels with TBS were examined using multivariable linear regression models. After adjusting for covariates, there was a negative association between serum PTH level and TBS (β = − 0.0034; 95% confidence interval, − 0.0050 to − 0.0017). However, in the subgroup analysis stratified by gender, race, and age, this association became negative only in Non-Hispanic White (β = − 0.0047, 95% CI: − 0.0071 to − 0.0048) and young people (age < 60) (β = − 0.0036, 95% CI: − 0.0057, − 0.0016), regardless of gender. In addition, the association of serum PTH with TBS was an U-shaped curve, with a point of inflection at 6.71 pmol/L. This study showed that serum PTH level was negatively associated with TBS. Maintaining PTH levels in a lower reasonable clinical range may be beneficial to bone health, especially for young non-Hispanic white.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis, the most common skeletal disorder of all, is a combination of bone mineral density (BMD) (i.e., quantity) and altered bone quality (i.e., quality), resulting in decreased bone strength with an increased risk of fractures at various sites like hip, wrist, and vertebrae1,2,3. In the United States, an estimated 10.2 million people aged 50 years and above have osteoporosis, and an additional 43.3 million have low bone mass4. In addition, there are more than 2 million fractures related to osteoporosis annually, which generates a cost of nearly USD 13.7–20.3 billion5. The incidence of fragility fractures is increasing rapidly due to the increasing population of older adults. Among fragility fractures, hip fractures are associated with the greatest disability and mortality6. Thus, osteoporosis as a systemic skeletal disease has a significant impact on the associated morbidity, mortality, health-care expenses, and burden of disease.

The BMD measured by dual X-ray bone densitometer (DXA) is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in the absence of definite brittle fracture7. Bone mineral density (BMD) is an important indicator of bone strength and fracture risk, but it does not fully reveal the status of bone microstructure. Relevant studies8 have found that about 45% of fractured and non-fractured individuals overlap in their BMD test results, suggesting that relying on BMD alone to predict fracture risk is not ideal. Trabecular bone score (TBS) is a novel gray-texture measurement method, that derived from the lumbar spine DXA imaging9. It uses experimental variograms of 2D projection images, quantifying variation in grey-level texture from 1 pixel to the adjacent pixels, and has been widely used in clinical evaluation of bone quality in recent years10. TBS reflects the bone microstructure index, which is directly related to the mechanical strength of bone11. Higher values of TBS indicate a better microarchitecture, whereas lower values indicate a degraded microarchitecture. In addition, TBS's prediction of fracture risk has been widely reported in cross-sectional, prospective and longitudinal studies, and has been endorsed by medical societies of bone field (IOF, the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, and the ISCD)12,13.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a polypeptide hormone secreted by the chief cells of the parathyroid gland, and it is composed of 84 amino acids14. Its analogues are currently approved as osteoanabolic drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis, such as teriparatide, which is the active fragment of the amino-terminal 1-34 of PTH15. PTH combines with parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor (PrlHlR) in bone tissue to play a role in regulating bone metabolism. However, PTH has a two-way regulatory effect of promoting bone formation in small dose and intermittent, and promoting bone resorption in large dose and continuous16.

PTH has a well-known role in mineral homeostasis and bone metabolism. However, to our knowledge, no study has yet analyzed the relationship between serum PTH levels and TBS in the general population. This analysis aimed to explore the relationship between the two by examining data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Materials and methods

Statement of ethics

NHANES is a cross-sectional study conducted on the American population, aimed at assessing the health and nutritional status of residents in the United States by collecting information on household demographics, health, and nutrition. Detailed data about it can be found on the internet and has been approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Ethics Review Board.

Study population

The health and nutritional status of adults and children in the USA and is administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHANES, a representative survey of the USA national population, utilizes a complex, multi-stage probability sampling design to offer extensive information on the nutrition and health of the USA population17. Its goal is to help improve the current situation and prevent potential future health problems. This nationwide survey is conducted every 2 years.

Our study was based on data from the NHANES between 2005 and 2006.

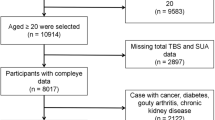

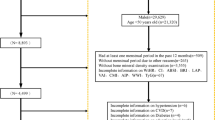

We included 3516 individual (1830 men and 1686 women). We excluded individuals with missing TBS (n = 6691) or serum PTH (n = 141) data. After selection, 3516 individual were included in our final analysis (Fig. 1).

Variables

BMD and TBS were assessed using DXA at the lumbar spine (L1–L4). The DXA scans were performed using a Hologic QDR-4500A fan-beam densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts), and all participant scans were reviewed and analysed by experts at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). For individuals aged 20 and older, the TBS software (Med-Imap SA TBS Calculator version 2.1.0.2) was used to calculate trabecular bone scores for each lumbar vertebra and an overall TBS score for the total lumbar spine. This assessment is based on analyzing the variations in gray levels within the pixels of an anterior–posterior lumbar spine DXA scan. To ensure the accuracy of the data, the entire DXA scanning process follows strict steps and implementation standards, and more detailed information is documented in the Body Composition Measurement Manual on the NHANES website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). The measurement of serum parathyroid hormone was carried out using the Elecsys 1010 fully automatic analyzer, employing the sandwich method as the measurement assay. The normal values for parathyroid hormone vary depending on the testing method used.The reference range for normal values in this study is 11-67 pg/mL (1.16–7.05 pmol/L). We chose these covariates based on their links to the outcomes of interest or a change in the effect estimate exceeding 10%. For covariates, continuous variables included age, Poverty income ratio (PIR), BMI, Total spine BMD, alkaline phosphatase, blood urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, total protein, serum uric acid, calcium, creatinine, phosphorus, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), C-reactive protein (CRP), Vit D. Categorical variables included gender, race, alcohol, coronary heart disease, physical activity, cancer, smoking.

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses by using R (http://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. All estimates were calculated by using sample weights following the analytical guideline edited by National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Three models were executed to adjust for covariates: Model 1 was non-adjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity. Model 3 included all variables from Model 2 and was further adjusted for PIR, BMI, total spine BMD, alkaline phosphatase, blood urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, total protein, serum uric acid, calcium, creatinine, phosphorus, HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Vit D, alcohol, coronary heart disease, physical activity, cancer, smoking. We also compared between-group differences using weighted chi-square tests and regression analyses. In addition, the linear or nonlinear association between PTH and TBS was further explored by introducing a generalised additive model (GAM) and smoothed curve fitting in the complete adjusted model. The presence of a non-linear relationship was determined by the log-likelihood ratio. If a non-linear relationship is confirmed, we will use a segmented linear regression model and determine the turning point through a recursive algorithm.

Ethics statement

According to local regulations and institutional requirements, this study did not necessitate ethical review and approval.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 3516 participants were included in our study, the detailed screening of study participants was presented in Fig. 1. The weighted characteristics of the participants subclassified based on PTH quartiles were demonstrated in Table 1.

Association between serum PTH levels and TBS

The relationship between the serum PTH level and TBS is presented in Table 2. In our analysis, we found a significant negative correlation between serum PTH levels and TBS. Even after adjusting for all covariates, this negative correlation still exists (− 0.0034; 95% CI, − 0.0050, − 0.0017; P < 0.001). To evaluate the robustness of results, PTH was treated as categorical variables (quartiles) for sensitivity analysis. The general trends were consistent in all models from the Q1 to Q4. In four distinct models, taking Q1 as a reference, differences were detected for TBS across PTH quartiles (all P for trend < 0.05) (Table 3).

Sex differences in the relationship between serum PTH levels and TBS

A linear regression of the sex specific association between the serum PTH level and TBS is shown in Table 4. A significant association was observed in men (β = − 0.0107; 95% CI, − 0.0133, − 0.0081) and women (β = − 0.0143; 95% CI, − 0.0169, − 0.0117). Even after adjusting for all covariates, negative associations were still evident in men (β = − 0.0030; 95% CI, − 0.0051, − 0.0008) and women (β = − 0.0038; 95% CI, − 0.0061, − 0.0015; P < 0.05).

Age differences in the relationship between PTH levels and TBS

A linear regression of the age specific association between the PTH level and TBS is shown in Table 4. A significant association was found in young people (age < 60) (β = − 0.0122; 95% CI, − 0.0146, − 0.0098; P < 0.000001). After adjusting for all covariates, negative associations were still noted in young people (β = − 0.0036; 95% CI, − 0.0057, − 0.0016; P < 0.05).

Race differences in the relationship between serum PTH levels and TBS

A linear regression of the race specific association between the serum PTH level and TBS is shown in Table 4. A significant association was found in Non-Hispanic White (β = − 0.0155; 95% CI, − 0.0182, − 0.0128; P < 0.000001). After adjusting for all covariates, negative associations were still noted in Non-Hispanic White (β = − 0.0047; 95% CI, − 0.0071, − 0.0022; P < 0.05).

Weighted generalized additive model and a smooth curve fitting

We used a weighted generalized additive model and a smooth curve fitting to address the non-linear relationship and confirm the results. The association between serum PTH levels and TBS is depicted. Each black point represents a sample. The solid rad line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit. After adjusting for all potential covariates, we found a nonlinear relationship between serum PTH levels and TBS (Fig. 2). The nonlinear relationship showed a U-shape with an inflection point of 6.71 pmol/L (Table 5). For serum PTH levels < 6.71 pmol/L, the effect size of the serum PTH level on TBS was -0.0102 (95% CI, − 0.0130, − 0.0073), and for serum PTH levels > 6.71 pmol/L, the effect size was 0.0022 (95% CI, − 0.0003, 0.0048). In the subgroup analysis stratified by gender, age and race/ethnicity, we found a U-shaped relationship in males, females, adults aged < 60, and non Hispanic white (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). The results of the inflection points are shown in Table 5.

The relationship between the serum PTH and TBS. (A) Each black point represents a sample. (B) Solid rad line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit. Age, Sex, Race, PIR, BMI, Total spine BMD, Alkaline phosphatase, Blood urea nitrogen, Total Cholesterol, Total protein, Serum uric acid, Calcium, Creatinine, Phosphorus, HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Vit D, Alcohol, Coronary heart disease, Physical activity, Cancer, Smoking were adjusted.

The association between serum PTH and TBS, stratified by gender. Age, Race, PIR, BMI, Total spine BMD, Alkaline phosphatase, Blood urea nitrogen, Total Cholesterol, Total protein, Serum uric acid, Calcium, Creatinine, Phosphorus, HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Vit D, Alcohol, Coronary heart disease, Physical activity, Cancer, Smoking were adjusted.

The association between PTH and TBS, stratified by age. Gender, Race, PIR, BMI, Total spine BMD, Alkaline phosphatase, Blood urea nitrogen, Total Cholesterol, Total protein, Serum uric acid, Calcium, Creatinine, Phosphorus, HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Vit D, Alcohol, Coronary heart disease, Physical activity, Cancer, Smoking were adjusted.

The association between serum PTH and TBS, stratified by ethnicity. Age, Sex, PIR, BMI, Total spine BMD, Alkaline phosphatase, Blood urea nitrogen, Total Cholesterol, Total protein, Serum uric acid, Calcium, Creatinine, Phosphorus, HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Vit D, Alcohol, Coronary heart disease, Physical activity, Cancer, Smoking were adjusted.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of American adults, we analyzed the independent effects of serum PTH levels on TBS in 3516 individuals and revealed an independent association between these two variables. We demonstrated a significant negative association between the serum PTH level and TBS in American adults after adjustment for all covariates. Our study suggested that elevated serum PTH levels correlated with decreased TBS, especially in non Hispanic white adults under 60 years old. We also observed a nonlinear U-shaped relationship between serum PTH levels and TBS, with a turning point at 6.71 pmol/L. For a serum PTH < 6.71 pmol/L, every 1 pmol/L increase in serum PTH level was associated with a decrease of 0.0102 in TBS, which was statistically significant. Similarly, this relationship also applies to non-Hispanic white individuals under the age of 60, regardless of gender. Therefore, we can conclude that maintaining PTH levels in a lower reasonable clinical range can help improve TBS indicators and reduce the risk of fractures, thus better preserving bone health.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a hormone produced by the parathyroid glands that regulates calcium and phosphorus metabolism, primarily acting on bones, kidneys, and the intestines18. The release of PTH is mainly controlled by Ca2+ and it also stimulates the kidneys (distal renal units) to reabsorb Ca2+ (along with magnesium) and inhibits the reabsorption of phosphate19. PTH promotes bone formation by encouraging the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells and inhibiting the release of sclerostin20,21. The formation of osteoclasts is regulated by the balance of receptor activator of nuclear factor k-B ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) concentrations22. PTH can regulate the expression of the RANKL and its soluble decoy receptor OPG in osteoblasts and bone cells, thereby affecting the generation of osteoclasts23,24. This effect of bone anabolism is used to treat severe osteoporosis, and is called “anabolic window”. This mechanism of bone formation without absorption stimulation may lead to the increase of newly formed trabecular bone and cortical bone by more than 20%25,26. Prior investigations have delineated that PTH is discharged in an oscillatory fashion, characterized by two distinct temporal phases27. The first phase, referred to as the homeostatic phase, encompasses a consistent frequency and amplitude of PTH secretions per diurnal cycle, primarily responsible for maintaining equilibrium in bone mass and orchestrating bone metabolism. The second phase, known as the dynamic phase, exhibits a fluctuating kinetics of PTH secretion on a minute-to-minute basis, predominantly serving to regulate serum calcium homeostasis.

Previous studies used high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) to investigate the relationship between bone microarchitecture and PTH level28,29. They revealed a association between these two factors. For instance, one study revealed that alterations in PTH secretion patterns were associated with decreased trabecular bone volume and increased cortical porosity in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism30. Although HR-pQCT has a higher resolution that allows for more precise detection of bone microarchitecture abnormalities, its application is not yet widespread. TBS is a novel gray-level texture analysis technique based on DXA images, which has been proven to be closely related to direct measurements of bone microarchitecture and the risk of fractures31. TBS analysis can easily be conducted from lumbar spine DXA images. Several studies have used a TBS threshold (TBS = 1.200) to identify patients at high risk of fractures32,33. Research by Boutroy et al. has shown that women without osteoporosis, but with TBS values below 1.209, have a significantly increased rate of fractures34. Another study indicated that approximately 72% of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) patients (TBS < 1.35) exhibit bone microarchitecture deterioration, whereas only 46% were diagnosed with osteoporosis or osteopenia through T-scores35. Similarly, recent research by Romagnoli et al. found that mild PHPT patients had lower TBS values compared to age-matched healthy controls, despite having similar lumbar spine BMD measured by DXA36. In addition, a cross-sectional study evaluated the relationship between TBS and volumetric BMD, bone microarchitecture, and bone stiffness. The results37 showed that TBS was positively correlated with total bone stiffness and other HRpQCT metrics, except for radial trabecular thickness and trabecular stiffness. It was inferred that TBS could reflect bone microstructure and bone strength to some extent and could be a useful tool to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

PTH plays a important role in the regulation of bone metabolism. Its regulation of bone metabolism is a complex process, capable of both stimulating osteoblasts to promote bone formation and activating osteoclasts to regulate bone resorption38,39. Studies have shown that the impact of PTH on bone metabolism varies depending on the method of administration, demonstrating a dual regulatory effect where small, intermittent doses promote bone formation, while large, continuous doses enhance bone resorption16,40,41. Lindsay et al.42 compared the changes in BMD in patients before and after intermittent administration of PTH and found that BMD increased significantly after treatment. The study by Ogita et al.43 confirmed through both in vivo and in vitro experiments that intermittent application of PTH can effectively promote the differentiation of preosteoblasts into osteoblasts. At the same time, PTH also significantly improves BMD in men with osteoporosis44. Furthermore, there is level I evidence indicating that human PTH significantly increases the BMD of all skeletal sites except the radius and significantly reduces the risk of new vertebral and non-vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women45. However, numerous studies have shown that patients with persistently high levels of serum PTH or hyperparathyroidism have reduced bone density and a corresponding increased risk of fracture46,47.

An increasing body of evidence shows that PTH is closely related to the development of osteoporosis. However, the direct impact of PTH on BMD remains unclear. In certain animal models, PTH has been observed to have a positive effect on BMD48,49. However, an observational study revealed that serum PTH levels are negatively correlated with total hip and femoral BMD50. A cross-sectional study involving British women found a negative correlation between PTH levels and overall BMD51. Similarly, a prospective study in Korea reported a negative correlation between PTH levels and BMD52. Mendelian randomization studies also observed a negative correlation between PTH and BMD, noting that this link strengthens with age53,54. Furthermore, it has been found that even among patients with PHPT who maintain normal BMD in the lumbar spine, the incidence of vertebral fractures significantly increases55. Therefore, serum PTH levels have important clinical significance for the treatment of osteoporosis and the reduction of fracture risk.

Clinically, it has been observed that patients with PHPT exhibit a correlation between high levels of PTH and reduced bone remodeling and BMD, primarily in the cortical bone54,56. Parathyroidectomy (PTX) is beneficial for the skeleton, significantly increasing the percentage of BMD57. However, for most patients with fragile fractures, the T-scores usually fall within the low bone mass or even the normal BMD range, failing to accurately reflect fracture risk. In contrast, the TBS serves as a tool to obtain more comprehensive skeletal data, helping to identify individuals with normal BMD but deteriorated microarchitecture58. Moreover, the ability of TBS to predict fractures is not affected by BMD and most clinical risk factors59,60. The study found that the average TBS values in patients with PHPT were significantly lower than those in the control group36. Among patients with PHPT and vertebral fractures, TBS was significantly lower than in patients without fractures. A prospective cohort study conducted in Italy showed a significant increase in TBS within two years after PTX61. These findings suggest that higher PTH levels may be associated with poorer bone microarchitecture and higher fracture risk. The results are basically consistent with our study, which proves the reliability of the study results.

Our research indicates a significant negative correlation between PTH levels and total TBS, a finding that remains statistically significant both before and after adjusting for covariates. In subgroup analyses, this negative correlation persists, especially pronounced among non-Hispanic whites under the age of 60. We also observed that, compared to patients under 60, older patients generally have lower TBS values. Additionally, we revealed a U-shaped relationship between PTH levels and TBS, which may correspond to the bidirectional regulatory effects of PTH on bone metabolism. This is particularly evident when serum PTH levels are low (PTH < 6.71 pmol/L), showing a significant statistical difference. Therefore, to promote bone health and further prevent fractures, it is advisable to maintain PTH levels within a relatively low and reasonable range in clinical practice. Notably, in patients with hyperparathyroidism, regardless of the presence of symptoms, early intervention to keep PTH at an appropriate level is recommended to reduce the risk of fractures.

A strength of our study is our use of a representative sample from the general population of the United States and the large sample size. However, the present study has some notable limitations. Firstly, the causal correlations of PTH with TBS were not assessed due to its cross-sectional design. A long-term observation study should be considered in future research. Secondly, we evaluate TBS through DXA, and the operator’s technology may affect the measurement. Thirdly, the study focused on the American population, and it is not clear whether this applies to other regions or countries.

Conclusion

Our research indicates that among the American population, elevated levels of PTH are associated with decreased TBS. There is a U-shaped curve relationship between the two, with the inflection point at 6.71 pmol/L. Concurrently, this U-shaped curve is also present in non-Hispanic whites under the age of 60, regardless of gender. This finding suggests that maintaining PTH levels as low as possible within the normal range may be more beneficial for bone health and better in preventing fractures.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx. The availability of this data is not restricted.

References

Méndez-Sánchez, L. et al. Calcium and vitamin D for increasing bone mineral density in premenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD012664. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012664.pub2 (2023).

Oniszczuk, A. et al. Sclerostin as a biomarker of physical exercise in osteoporosis: A narrative review. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 5(13), 954895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.954895 (2022).

Kazemian, E. et al. Effect of supplemental vitamin D3 on bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 81(5), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac068 (2023).

Sarafrazi, N., Wambogo, E. A. & Shepherd, J. A. Osteoporosis or low bone mass in older adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief 405, 1–8 (2021).

Patel, K., Salama, S. & Cottreau, J. Osteoporosis: A review of novel agents. Orthop. Nurs. 41(6), 428–433. https://doi.org/10.1097/NOR.0000000000000899 (2022).

Sun, W., Zhang, X. A. & Wang, Z. The role and regulation mechanism of Chinese traditional fitness exercises on the bone and cartilage tissue in patients with osteoporosis: A narrative review. Front. Physiol. 28(14), 1071005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1071005 (2023).

Blaty, T. et al. DXA evaluation of femoral bone mineral density and cortical width in patients with prior total knee arthroplasty. Osteoporos. Int. 30(2), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4682-7 (2019).

Bliuc, D. et al. The association between multimorbidity and osteoporosis investigation and treatment in high-risk fracture patients in Australia: A prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 20(1), e1004142. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004142 (2023).

Goel, H., Binkley, N., Hans, D. & Leslie, W. D. Bone density and trabecular bone score to predict fractures in adults aged 20–39 years: A registry-based study. Osteoporos. Int. 34(6), 1085–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06722-w (2023).

Ryang, S., Jeon, Y. K., Goh, T. S., Kim, I. J. & Kim, K. Trabecular bone score and central quantitative computed tomography for the prediction of vertebral fragility fractures in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Metab. 30(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2023.30.1.77 (2023).

Hans, D. et al. Long-term effect of denosumab on bone microarchitecture as assessed by tissue thickness-adjusted trabecular bone score in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Results from FREEDOM and its open-label extension. Osteoporos. Int. 34(6), 1075–1084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06708-8 (2023).

Yang, S. W., Lin, Y. J., Cheng, Y. W., Chen, Y. Y. & Chen, W. L. Unraveling the relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and trabecular bone score in American adults. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 132(10), 16311. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16311 (2022).

Palomo, T. et al. Update on trabecular bone score. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 66(5), 694–706. https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000559 (2022).

Heck, A. et al. Endocortical trabecularization in acromegaly: The cause for the paradoxically increased vertebral fracture risk?. JBMR Plus. 7(10), e10787. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10787 (2023).

Rosen, C. J. Insulin-like growth factor-I and parathyroid hormone: potential new therapeutic agents for the treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 6(9), 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1517/13543784.6.9.1193 (1997).

Zhu, Z. et al. Association between age-related macular degeneration and subjective cognitive complaints. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104(9), 1228–1233. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314853 (2020).

Vora, N. M. et al. Effect of exercise on serum calcium and parathyroid hormone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 57(5), 1067–1069. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-57-5-1067 (1983).

Goltzman, D. Physiology of Parathyroid Hormone. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 47(4), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2018.07.003 (2018).

Mariotti, V. et al. Assessing fracture risk in early stage breast cancer patients treated with aromatase-inhibitors: An enhanced screening approach incorporating trabecular bone score. J. Bone Oncol. 7, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2016.10.004 (2016).

Ohishi, M. & Schipani, E. PTH and stem cells. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 34, 552–556. https://doi.org/10.3275/7620 (2011).

Zhang, L. X., Balani, Y. M., Trinh, S., Kronenberg, H. M. & Mu, Y. Differential effects on bone and mesenchymal stem cells caused by intermittent and continuous PTH administration. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 98, 781–787 (2018).

Kearns, A. E., Khosla, S. & Kostenuik, P. J. Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin regulation of bone remodeling in health and disease. Endocr. Rev. 29(2), 155–192. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2007-0014 (2008).

Kanzawa, M., Sugimoto, T., Kanatani, M. & Chihara, K. Involvement of osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor in the stimulation of osteoclast formation by parathyroid hormone in mouse bone cells. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 142, 661–664. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.0.1420661 (2000).

O’Brien, C. A., Nakashima, T. & Takayanagi, H. Osteocyte control of osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 54, 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2012.08.121 (2013).

Iida-Klein, A., Lu, S. S., Cosman, F., Lindsay, R. & Dempster, D. W. Effects of cyclic vs. daily treatment with human parathyroid hormone (1–34) on murine bone structure and cellular activity. Bone. 40(2), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.010 (2007).

Prank, K. et al. Time series prediction of plasma hormone concentration Evidence for differences in predictability of parathyroid hormone secretion between osteoporotic patients and normal controls. J. Clin. Invest. 95(6), 2910–2919. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI117998 (1995).

Pfeilschifter, J. & Mundy, G. R. Modulation of type beta transforming growth factor activity in bone cultures by osteotropic hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84(7), 2024–2028. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.84.7.2024 (1987).

Cusano, N. E. et al. Changes in skeletal microstructure through four continuous years of rhPTH(1–84) therapy in hypoparathyroidism. J. Bone Miner. Res. 35(7), 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4005 (2020).

Walker, M. D. et al. Effect of concomitant vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency on lumbar spine volumetric bone mineral density and trabecular bone score in primary hyperparathyroidism. Osteoporos. Int. 27(10), 3063–3071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3637-0 (2016).

Cipriani, C. et al. Comparative effect of rhPTH(1–84) on bone mineral density and trabecular bone score in hypoparathyroidism and postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 33(12), 2132–2139. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3554 (2018).

Pothuaud, L., Carceller, P. & Hans, D. Correlations between grey-level variations in 2D projection images (TBS) and 3D microarchitecture: applications in the study of human trabecular bone microarchitecture. Bone. 42(4), 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.018 (2008).

Lamy, O. et al. What is the performance in vertebral fracture discrimination by bone mineral density (BMD), micro-architecture estimation (TBS), body mass index (BMI) and FRAX in stand-alone or combined approaches: The OsteoLaus Study [abstract]. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27(suppl 1), S236 (2012).

Vasic, J. et al. Spine micro-architecture estimation (TBS) discriminates major osteoporotic fracture from controls equally well than site matched BMD and independently: The Eastern Europe TBS study [abstract]. Osteoporos. Int. 23(suppl 2), S327 (2012).

Boutroy, S. et al. Trabecular bone score improves fracture risk prediction in non-osteoporotic women: the OFELY study. Osteoporos. Int. 24, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2188-2 (2013).

Hans, D., Goertzen, A. L., Krieg, M. A. & Leslie, W. D. Bone microarchitecture assessed by TBS predicts osteoporotic fractures independent of bone density: The Manitoba study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2762–2769. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.499 (2011).

Romagnoli, E. et al. “Trabecular Bone Score” (TBS): an indirect measure of bone micro-architecture in postmenopausal patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Bone. 53(1), 154–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2012.11.041 (2013).

Hansen, S., Shanbhogue, V., Folkestad, L., Nielsen, M. M. & Brixen, K. Bone microarchitecture and estimated strength in 499 adult Danish women and men: a cross-sectional, population-based high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomographic study on peak bone structure. Calcif. Tissue Int. 94(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-013-9808-5 (2014).

Jilka, R. L. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone 40(6), 1434–1446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017 (2007).

Silva, B. C., Costa, A. G., Cusano, N. E., Kousteni, S. & Bilezikian, J. P. Catabolic and anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on the skeleton. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 34(10), 801–810. https://doi.org/10.3275/7925 (2011).

Qin, L., Raggatt, L. J. & Partridge, N. C. Parathyroid hormone: A double-edged sword for bone metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 15(2), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2004.01.006 (2004).

Frolik, C. A. et al. Anabolic and catabolic bone effects of human parathyroid hormone (1–34) are predicted by duration of hormone exposure. Bone 33(3), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00202-3 (2003).

Lindsay, R. et al. A novel tetracycline labeling schedule for longitudinal evaluation of the short-term effects of anabolic therapy with a single iliac crest bone biopsy: early actions of teriparatide. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21(3), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1359/JBMR.051109 (2006).

Ogita, M., Rached, M. T., Dworakowski, E., Bilezikian, J. P. & Kousteni, S. Differentiation and proliferation of periosteal osteoblast progenitors are differentially regulated by estrogens and intermittent parathyroid hormone administration. Endocrinology 149(11), 5713–5723. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2008-0369 (2008).

Kurland, E. S. et al. PTH as a therapy for idiopathic osteoporosis in men: Effect on bone mineral density and bone marker. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 85(9), 3069–3076 (2000).

Cranney, A. et al. Parathyroid hormone for the treatment of osteoporosis: A systematic review. CMAJ. 175(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050929 (2006).

George, J. A., Micklesfield, L. K., Norris, S. A. & Crowther, N. J. The association between body composition, 25(OH)D, and PTH and bone mineral density in black African and Asian Indian population groups. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99(6), 2146–2154. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3968 (2014).

Stein, E. M. et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with abnormal cortical and trabecular microstructure and reduced bone stiffness in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28(5), 1029–1040. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.1841 (2013).

Znorko, B. et al. RANKL/OPG system regulation by endogenous PTH and PTH1R/ATF4 axis in bone: Implications for bone accrual and strength in growing rats with mild uremia. Cytokine 106, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.03.002 (2018).

Oest, M. E., Mann, K. A., Zimmerman, N. D. & Damron, T. A. Parathyroid hormone (1–34) transiently protects against radiation-induced bone fragility. Calcif. Tissue Int. 98(6), 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-016-0111-0 (2016).

Gao, C. et al. The levels of bone turnover markers 25(OH)D and PTH and their relationship with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women in a suburban district in China. Osteoporos. Int. 28(1), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3692-6 (2017).

Mendes, M. M., Hart, K. H., Lanham-New, S. A. & Botelho, P. B. Association between 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, vitamin D and calcium intake, and bone density in healthy adult women: A cross-sectional analysis from the D-SOL study. Nutrients. 11(6), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061267 (2019).

Choi, S. W. et al. The association between vitamin D and parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density: the Dong-gu Study. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 34(5), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-015-0696-9 (2016) (Epub 2015 Jul 30).

Qu, Z., Yang, F., Hong, J., Wang, W. & Yan, S. Parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105(11), dgaa579. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa579 (2020).

Parisien, M., Silverberg, S. J., Shane, E., Dempster, D. W. & Bilezikian, J. P. Bone disease in primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 19(1), 19–34 (1990).

Vignali, E. et al. Morphometric vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94(7), 2306–2312. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-2006 (2009).

Bandeira, F. & Cassibba, S. Hyperparathyroidism and bone health. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 17(7), 48 (2015).

Arboiro-Pinel, R., Mahillo-Fernández, I. & Díaz-Curiel, M. Primary hyperparathyroidism: Assessment of the effects of parathyroidectomy using dual X-Ray absorptiometry, trabecular bone score, and dual X-Ray absorptiometry-based three-dimensional modeling. Endocr Pract. 30(4), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2024.01.004 (2024).

Harvey, N. C. et al. Trabecular bone score (TBS) as a new complementary approach for osteoporosis evaluation in clinical practice. Bone 78, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2015.05.016 (2015).

Martineau, P. et al. Clinical utility of using lumbar spine trabecular bone score to adjust fracture probability: The manitoba BMD cohort. J. Bone Miner. Res. 32(7), 1568–1574. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3124 (2017).

Hans, D., Goertzen, A. L., Krieg, M. A. & Leslie, W. D. Bone microarchitecture assessed by TBS predicts osteoporotic fractures independent of bone density: The Manitoba study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26(11), 2762–2769. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.499 (2011).

Eller-Vainicher, C. et al. Bone quality, as measured by trabecular bone score, in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 169(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-0305 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the participants of the NHANES study.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Department of Health of Zhejiang Province (2020KY408 to Dr. Jun Zhang, 2022KY548 and 2023KY494 to Dr. Haiyu Shao, and 2022KY608 to Dr. Tingxiao Zhao), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LGD22H060004 to Dr. Jun Zhang), and Hangzhou Medical and Health Technology Project (B20200282 to Dr. Yongguang Wang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z. and J.Z. designed the initial study. T.Z., Y.L., J.Z., J.X., and J.T. managed and retrieved the data, contributed to primary data analysis and explanation, and drafted the initial script. C.X. and Y.K. decided on the methods of data collection and were responsible for the decisions regarding data analysis. T.Z., H.S., Y.W., and J.Z. conceptualized the study, supervised all aspects of the study, critically reviewed and revised the initial script, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, T., Li, Y., Tian, J. et al. Unraveling the relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels and trabecular bone score: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 13065 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63979-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63979-9

This article is cited by

-

Investigation of clinical characteristics of COVID-19 infection in rheumatoid patients on immunosuppressive drugs: a retrospective case–control study

The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine (2025)

-

Bilateral femoral neck fractures in pregnancy suggestive of transient osteoporosis of the hip in a patient with hyperparathyroidism: a case report

Osteoporosis International (2025)