Abstract

Aedes aegypti is vector of many arboviruses including Zika, dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and Chikungunya. Its control efforts are hampered by widespread insecticide resistance reported in the Americas and Asia, while data from Africa is more limited. Here we use publicly available 729 Ae. aegypti whole-genome sequencing samples from 15 countries, including nine in Africa, to investigate the genetic diversity in four insecticide resistance linked genes: ace-1, GSTe2, rdl and vgsc. Apart from vgsc, the other genes have been less investigated in Ae. aegypti, and almost no genetic diversity information is available. Among the four genes, we identified 1,829 genetic variants including 474 non-synonymous substitutions, some of which have been previously documented, as well as putative copy number variations in GSTe2 and vgsc. Global insecticide resistance phenotypic data demonstrated variable resistance in geographic areas with resistant genotypes. Overall, our work provides the first global catalogue and geographic distribution of known and new amino-acid mutations and duplications that can be used to guide the identification of resistance drivers in Ae. aegypti and thereby support monitoring efforts and strategies for vector control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mosquitoes of the genus Aedes, particularly Aedes (Ae.) aegypti, are responsible for the transmission of many arboviral diseases, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever, West Nile and Chikungunya, resulting in millions of infections globally per year with limited treatment and vaccination options1. The geographical distribution of Ae. aegypti has expanded considerably in recent years, predominantly due to adaptation of this vector to urban environments, climate change and the globalization of human activities, thereby increasing the risk of resurgence and spread of arbovirus infections2,3,4. Compounding the problem is the global emergence of insecticide resistance among Ae. aegypti and other mosquito species, which is threatening to jeopardise the operational effectiveness of vector control campaigns.

Resistance to the four most common classes of insecticides used against adult mosquitoes (carbamates, organochlorines, organophosphates, and pyrethroids) has now been documented worldwide. Resistance in many mosquito species has been associated with target site mutations, metabolic detoxification, cuticular alterations and behavioural avoidance5,6 with a suite of alternative resistance mechanisms being revealed7,8,9,10. Target site resistance is related to mutations in genes that code for insecticide target molecules, such as the voltage-gated sodium channel (vgsc also known as knockdown resistance; kdr), acetylcholinesterase-1 (ace-1 also known as AChE1) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (resistance to dieldrin; rdl). Mutations in glutathione-s-transferase epsilon two (GSTe2), which encodes an insecticide metabolising enzyme, have also been associated with resistance5,11,12,13. The vgsc is a large protein that is an integral part of the insect nervous system. DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) and pyrethroid insecticides interfere with the vgsc by prolonging the pore open state leading to insect paralysis and death14. In the reference insect for this gene, Musca domestica, the most frequent kdr resistance mutations are S989 and L101415. In Ae. aegypti, the 1014 codon requires at least two mutations to change to a M. domestica amino acid known to cause resistance; thus, the substitution L1014F, seen pervasively in Anopheles mosquitoes, has not been observed in this species11. Instead, F1534C/L, V1016I/G, I1011V/M and V410L mutations have been associated with pyrethroid resistance in Ae. aegypti and confirmed experimentally6. Other amino acid substitutions reported previously in Ae. aegypti include G923V, L982W, S989P, T1520I and D1763Y11,16,17,18. Many of these mutations are often found in combination and appear only on specific continents. For example, V1016G and S989P appear limited to Asia, while V1016I has only been identified in the Americas and Africa and 723T only in the Americas19.

The ace-1 gene encodes acetylcholinesterase (AchE1), which is responsible for hydrolysis of acetylcholine terminating the transmission of neural signals. Organophosphates and carbamates bind to the acetylcholinesterase active site which inhibits hydrolysis and consequently neural signal termination, leading to insect death. Unlike mammals and some insects (including Drosophila melanogaster), mosquitoes usually have two copies of the ace-1 gene. In Anopheles mosquitoes, the G119S amino acid substitution in ace-1 is generally associated with resistance (all coordinates are based on Torpedo californica)20,21. As with the vgsc, in Ae. aegypti such an amino acid change requires two mutations and has only been observed in one study in India22. Despite the lack of described mutations in ace-1, resistance to organophosphates in Aedes is widespread in the Americas and Asia, while data from Africa is limited6.

The rdl mutation is found in the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor gene that controls neural signal inhibition through opening and closing of the transmembrane chloride channel on the cells of the mosquito nervous system. Cyclodienes (e.g., dieldrin) prevent interaction of GABA with its receptor, leading to neuron hyperexcitation and eventual insect death23,24,25,26. The most common resistance mutation in this gene is A301S/G (D. melanogaster numbering) and is observed in multiple insects including mosquitoes of the Anopheles and Aedes genera21,27. Despite a ban on the use of cyclodienes in 200128 due to their slow degradation and environmental persistence, rdl mutations have persisted for decades later in vector populations, suggesting that they impart limited fitness costs29,30.

Unlike rdl, ace-1 and vgsc, which are targets of insecticides, the homodimer glutathione S-transferase (GST) is a detoxifying enzyme. Most organisms, including Ae. aegypti, have multiple GST enzymes of which epsilon two (GSTe2) has been associated with resistance to both DDT and pyrethroids6,12,31,32. The GSTe2 gene contributes to insecticide resistance through both enzyme overexpression and point mutations. Increased expression of this gene was linked to DDT resistance in An. gambiae5,25,26,33. The L119F substitution in GSTe2 was observed to enhance resistance to both DDT and pyrethroids in An. funestus, and I114T exacerbated resistance to DDT in An. gambiae5,33,34,35. In Ae. aegypti, L111S and I150V mutations have been linked to temephos resistance in silico36.

Despite observed phenotypic resistance of Ae. aegypti to all main insecticide classes across many countries in Africa, Americas, and Asia6, the distribution of genetic variants in underlying candidate genes is less studied across Aedes populations compared to Anopheles species. Here, we examined a large (n = 729), globally diverse dataset of publicly available Ae. aegypti whole genome sequencing (WGS) data to uncover the genetic diversity present in vgsc, ace-1, rdl and GSTe2. The diversity in insecticide resistance loci was interpreted alongside current global trends in phenotypic insecticide resistance in Ae. aegypti. This data provides a catalogue of genetic variants that could be involved in insecticide resistance and supports further studies on the molecular surveillance of emerging and spreading insecticide resistance mechanisms amongst Ae. aegypti populations.

Material and methods

Aedes aegypti genomic data

We searched the NCBI SRA database for “Aedes aegypti” sample data and restricted results to WGS libraries where the number of bases contained implied at least fivefold coverage when mapped to the reference genome AaegL5 (GCF_002204515.2)32. We obtained a total of 703 WGS Ae. aegypti (non-AaegL5) libraries from 15 countries, across Africa (n = 476, 8 countries), the Americas (n = 191, 3 countries), Oceania (n = 16, 1 country) and Asia (n = 20, 1 country), and 26 colony samples of which 20 had known country of collection. Additionally, we included 7 Ae. mascarensis samples from Madagascar (n = 4) and Mauritius (n = 3) as outgroup37,38,39,40,41 (Table S1).

Insecticide resistance phenotypic data

Insecticide response data was only available for the Bora-Bora susceptible reference strain, which has been maintained in the insectary for 134 generations without any exposure to insecticides42 and the Nakon Sawan reference strain, which is resistant to deltamethrin and temephos41,43, (Table S2). Global insecticide resistance phenotype data was retrieved from the IR Mapper tool44 (sourced on 19/04/2023), which covered 73 countries of which 8 overlap with samples in this study. No data was available for 5 countries (Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, South Africa, and Uganda); an additional literature search in PubMed failed to retrieve additional publicly available phenotypic data for Ae. aegypti in these countries. We included the data where the phenotype was tested with World Health Organization (WHO) tube or bottle bioassay or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) bottle bioassay. Phenotypic data based solely on PCR or RT-PCR methods were excluded. Overall, we analysed 3172 data points for 19 different insecticides across four insecticide classes (Pyrethroids, Organophosphates, Organochlorines and Carbamates) (Table S3). Data points from IR mapper were reported as susceptible, possible resistance or resistant based on mortality as per WHO and CDC guidelines.

Bioinformatic analysis

We aligned the WGS libraries using bowtie2 (v2.4.1) software (with a setting --fast-local)45. We processed the alignment files using samtools (v1.7) software and SNPs were called using the GATK HaplotypeCaller tool (v4.1.9) with default settings46,47. A minimum coverage of 5-fold was used to accept SNPs. We merged the individual VCF files into a multi-sample file using BCFtools (v1.9)48. The impact of SNPs in the multi-sample VCF was predicted using snpEff software (v5.0) with AaegL5 genome annotation (GCF_002204515.2)49. The alignment process was performed against the mRNA sequences of twenty Ae. aegypti genes (Table 1). Four were loci linked to insecticide resistance [vgsc (XM_021852340.1), rdl (XM_021840622.1), ace-1 (XM_021851332.1) and GSTe2 (XM_021846286.1)] and the remaining sixteen genes were used to establish population structure. One of these was mitochondrial cox1 (YP_009389261.1) and the remaining fifteen genes were evenly spread across all three Ae. aegypti chromosomes (Table 1). These 15 genes were determined to have unique genome-wide exon sequences (using NCBI BLASTn v2.9.0 with—word-size 28 and—evalue 0.01) which minimised potential mis-mapping of WGS reads to the Ae. aegypti genome known to contain many duplications50. Read coverage per nucleotide per gene was calculated using the samtools “depth” function and was used to identify possible gene duplications in samples48. We merged the coverage data into a single data matrix and removed all regions except gene exons, because intronic regions contained high numbers of repeats. For each sample, we divided each per base coverage value by that sample’s overall median coverage across all genes, except vgsc and GSTe2, which may have copy number variants. We applied UMAP (v0.5.1) software (with a Euclidean distance metric) on this scaled matrix to identify gene clusters based purely on the coverage51.

Population genetics analysis

To determine population structure, we used UMAP software (with Russell-Rao distance metric) on the multi-sample VCF, followed by application of HDBSCAN (v0.8.28)51,52 to determine sample clustering (see53,54,55 for recent applications). This work was performed in python (v3.7.6), with scripts available from https://github.com/AntonS-bio/resistance-AedesAegypti. Linkage disequilibrium was calculated using vcftools on phased vcf files created with beagle (v 22Jul22.46e) software to provide a R2 value for each combination of non-synonymous mutations by sample country. Plots of these values were visualised using the gaston (v1.5.9) package in R.

Protein structure modelling

Protein structure modelling was performed using AlphaFold Multimer software with full protein databases56,57. When referring to substitutions and their effects on proteins, we have followed the established nomenclature based on reference resistance linked proteins and structures in the protein databank: ACE1 (2C4H; Tetronacre californica), GABA receptor (NP_729462.2; Drosophila melanogaster), GSTe2 (XP_319968.3; An. gambiae) and VGSC (NP_001273814.1; Musca domestica)58,59. Unless otherwise specified, all substitution coordinates are with respect to these reference sequences.

Results

Genetic variation and population structure

Across the 729 Aedes samples from 15 countries, a total of 1829 SNPs (474 non-synonymous (NS)) were detected across the CDS of four insecticide resistance associated genes (vgsc, rdl, ace-1 and GSTe2), and 9673 SNPs were identified across the CDS of 15 non-resistance associated genome-wide gene (Tables 1, 2, Table S4).

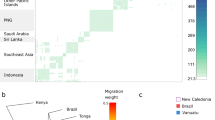

Using the SNPs from the CDS of 15 genes not associated with insecticide resistance, a UMAP clustering analysis revealed five distinct clusters (Fig. 1A), broadly linked to: (i) eastern Kenya and South Africa (n = 112); (ii) west, central Africa and west Kenya (n = 350); (iii) the Americas, Thailand, and other (n = 258); (d) the Bora-Bora mosquito line from French Polynesia (n = 9); (e) Ae. mascarensis from Madagascar and Mauritius (n = 7). Similar results were obtained when analysing only the 1829 SNPs in genes that are associated with resistance (Fig. 1B). These results are broadly consistent with previous reported population structure of Ae. aegypti using SNPs and microsatellite data, where African samples formed one cluster and samples from Asia, America and the Caribbean comprised another cluster60; however, more focused studies provide better understanding of population structure38,60,61,62,63. As we observed a separation of most eastern Kenyan samples (n = 121) from west Kenya (n = 37), we investigated the genotype data in these groups independently. Some eastern Kenyan samples (n = 14/121) from a human- biting colony of domestic Ae. aegypti, originally collected indoors in Rabai60,64, clustered with non-African samples (Americas and Thailand and other cluster), as previously observed. When including only non-African samples, the UMAP clustering analysis revealed modest separation of the samples from Brazil, Mexico, French Polynesia, American Samoa and Thailand. For the samples from Africa, clustering separated east Kenyan samples from the rest (Fig. S1). The same patterns were detected across both resistance and non-resistance genes (Fig. S1). Clustering using mitochondrial cox1 gene was different from the results based on chromosomal loci (Fig. 1C–F). In multiple samples, SNPs had heterozygous cox1 genotypes possibly multiploidy due to the presence of previously described copies of nuclear mitochondrial (NUMT) DNA which could confound clustering65,66.

Genetic variation across insecticide resistance associated genes

Vgsc

In the vgsc gene, a total of 1075 SNPs (202 non-synonymous; NS) were identified, of which 36 NS SNPs were present in > 1 sample, including eight mutations previously linked to insecticide resistance (V410L, G923V, S989P, I1011M, V1016I/G, T1520I and F1534C) (Table 2, Table S4). We did not observe any other pyrethroid resistance associated substitutions such as L982W, detected previously in Vietnam and Cambodia, and D1763Y reported in Taiwan. However, the D1763G mutation was present in a single USA sample11,16,17,18. The most frequent mutations were F1534C (39%), S723T (23%), V410L (22%) and V1016I (22%) (Fig. 2). The most prevalent F1534C mutations occurred in nearly all samples from the Americas (186/191) and Thailand (20/20). The frequency of F1534C was lower in African samples, appearing only in Burkina Faso (n = 20/34), Ghana (n = 33/58), Nigeria (n = 1/19) and East Kenya (n = 8/107). The F1534C mutation was accompanied by V1016I, S723T and V410L substitutions in most samples from USA, Burkina Faso, and Mexico, as well as in a single Nigerian sample. In Thailand, F1534C co-occurred in many samples with V1016G, T1520I and S989P (Table 2).

Several mutations were found to be regionally specific. The V1016G mutation was found only in Asia (Thailand) while V1016I was detected in USA, Mexico, and a few countries in Africa19. The M944V substitution was unique to East Kenya (n = 42/107), L946G was almost exclusive to Brazil (n = 15/16) except for one Nigerian sample. The V1016G, T1520I (n = 10/20), S989P (n = 7/20), and S66F (n = 11/20) were also almost exclusive to Thailand, apart from a single Nigerian and a Brazilian sample (Table 2). Two conservative in-frame insertions occurred in ~ 20% of west and central African samples, which included an addition of amino acid Glycine (Gly) into a sequence of four consecutive Gly (positions 2047–2050), and an addition of Serine-Glycine (positions 2016 and 2017).

Rdl (GABA receptor)

In the rdl gene, we identified a total of 244 SNPs (64 NS), of which only 17 NS SNPs occurred in > 1 sample and the most frequent were G84A, S115T and A301S. The S115T substitution was present in almost all samples (n = 733/736) including all Ae. mascarensis (Fig. 2, Table 2). The T115 is the dominant allele in An. gambiae suggesting that the common ancestor of both An. gambiae and Ae. aegypti had the 115T allele, and a mutation in the Ae. aegypti reference strain changed T to S67.

The previously described A301S substitution, associated with resistance to organochlorines, was frequent in the USA (n = 97/160) and Thailand (n = 11/20), and infrequent in a few countries in Africa (Table 2)21,27. This substitution is located on the a-helix forming the protein pore (Fig. S2). The only other notable mutation was E84D present in 18 samples (Africa n = 13, Thailand n = 5), and located on the outward facing section of the protein but could not be robustly modelled by the AlphaFold software.

Ace-1

A total of 243 SNPs were identified in the ace-1 gene, of which 99 led to amino-acid substitutions, with 30 present in > 1 sample (Table 2). Only 6 amino-acid substitutions (G12S, H35L, D131Q, L687F, S693A, C699S) occurred in > 10 samples (Fig. 2). The most frequent mutation was C699S (n = 42/736), which was present in samples from west and central Africa (n = 29) and the Americas (n = 13). The second most frequent substitution was H35L (5.0%) observed only in west and central African samples. The third most frequent substitution was G12S (4.8%) found mostly in the Americas (n = 26/37) and Thailand (n = 7/37) (Table 2). All three substitutions are defined in Ae. aegypti coordinates because these amino acids are outside the range of the T. californica reference ACE1 (PDB: 2C4H). In fact, only 20 substitutions had a corresponding coordinate in the T. californica protein (Table 2). The only substitution in Ae. mascarensis was T55P (T. californica coordinates) present in all samples of this species. We modelled the ACE1 protein structure in AlphaFold, and in line with results of crystallographic experiments, the residues 1–131 and 660–702 were disordered, likely reflecting their role in anchoring the protein to the cellular membrane and receptor proteins68. The G119S resistance substitution commonly reported in ACE1 in other insect species was not detected in this dataset. This absence is likely because G119S would require two nucleotide substitutions in Ae. aegypti. Further, instead of two ace genes commonly found in insects, the Ae. aegypti reference genome has four ace genes including one analysed here (LOC5578456) and three others (LOC5574466, LOC5575867, LOC5570776). The mRNA encoding the cognate proteins had < 5% pair-wise coverage which rules out recent duplication as the origin of these genes. One of these loci (LOC5570776) had the 119S amino acid. We found that despite the very high prevalence of transposable elements in Ae. aegypti, this gene remains uninterrupted by them suggesting this locus might be functional32.

GSTe2

The GSTe2 gene has a variable copy number in Ae. aegypti, and the reference genome contains four copies of this gene32. The variable copy number was also evident in our analysis. Because we used short read data, we could not robustly assign each mutation to individual GSTe2 loci. A total of 267 SNPs were detected in GSTe2 genes, with 109 leading to amino-acid substitutions, of which 42 were present in >1 sample (Table 2). Seven substitutions were highly frequent: I150V (n = 670), A198E (n = 670), C115F (n = 542), L111S (n = 288), I169S (n = 172), L9I (n = 151) and C115S (n = 108) (Fig. 2). The samples from Thailand had neither synonymous nor missense mutations in GSTe2, which we confirmed by visual examination of the read alignments. The C115F substitution was present in almost all countries (except Thailand and Mauritius). The C115S substitution was most common in Africa (n = 101/353). In addition to C115F/S, we observed two other common substitutions (L111S, L9I) at the DDT binding site69. The L111S substitution (n = 288/736) appears globally distributed, and L9I was found mainly in Africa and USA, but not observed in Ae. mascarensis. The I169S mutation was common in the presence of L9I. Based on a high confidence AlphaFold protein structure model for GSTe2, the I169S mutation is not part of either glutathione or DDT binding site; however, it interacts with both F115 and M111, which are part of the glutathione binding pocket (Fig. S3).

Gene duplications

Gene variable copy numbers were identified based on excess median-scaled read coverage. For the vgsc gene, a group of 26 samples had potential duplications, with a median-scaled coverage of 1.4-fold compared to 1.0-fold for the rest of the samples. The samples in this set came from a disparate group of countries: Senegal (n = 13), American Samoa (n = 4), and USA (n = 3), Mexico (n = 2), Mauritius (n = 2), Kenya (n = 1) and Thailand (n = 1) (Table S1).

For GSTe2, two groups of samples had likely copy number events. First, a group of samples with median 4.2-fold median-scaled coverage consisting of samples from Thailand (n = 27/28) including samples from the Nakh lab strain, USA (n = 38/160), Mexico (n = 5/15), Brazil (n = 1/16) and two from the Vienna F4 colony70. A second group consisted of samples from USA (n = 15/160) and Mexico (n = 9/16) with median-scaled coverage of 9.3-fold compared to 0.9-fold for the rest of the samples (Table S1, Fig. S4). In our search of the literature, we did not identity previous reports of such high duplication rate; this finding requires further validation. However, this result also shows that majority of Ae. aegypti reference sequence have single copy of GSTe2, in contrast to the reference strain which has four32.

Linkage disequilibrium between missense mutations

We examined the geographical distribution of the non-synonymous SNPs across the four resistance genes and observed that many mutations co-occur together in certain populations (Fig. 2). For each locus, per population, we assessed the pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) of non-synonimous SNPs. We found twenty-seven pairwise SNPs that had, without adjusting for multiple testing, an R2 value above 0.5 (GSTe2 n = 15, vgsc n = 9, ace-1 n = 2, and rdl n = 1) (Table S5). The GSTe2 mutations L9I/I169S (Burkina Faso, Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, Uganda) and I150V/A198E (Kenya, French Polynesia, Mauritius) were detected with a R2 > 0.5 in several countries. In the vgsc gene, several SNPs that have been associated with insecticide resistance also had R2 > 0.5, particularly V410L, V1016I, V1016G and F1534C.

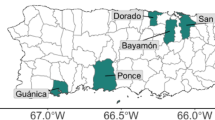

Geographical distribution of insecticide resistance mutations and phenotypes

The IR mapper was used to obtain phenotypic data for 8 of the 15 countries examined in this study. These phenotypes show disparity between the availability of phenotypic and genomic data, for example, Brazil and Thailand have the highest number of bioassay records while only having 16 and 20 genomic sequences available, respectively. However, in some countries there was genomic data available with limited phenotypic data, such as Uganda and Kenya. Phenotypic data available for each country from IR Mapper was mapped to the co-occurrence of nine mutations previously associated with insecticide resistance (A301S (RDL) associated with organochlorine resistance, and F1534C, T1520I, V1016I/G, I1011V/M, S989P, G923V, V410L (VGSC) all associated with pyrethroid resistance). Thailand, Burkina Faso, and the USA had the highest proportion of samples with several known insecticide resistance mutations (Fig. 3). This is supported by the Thailand phenotypic data from IR Mapper, which shows reports of resistance to all four main insecticide classes in this country (Fig. 4), particularly to organochlorines, carbamates and pyrethroids. Elevated levels of resistance have also been reported in southeast Asian regions, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand; however, there are gaps in the genomic data from these countries71,72,73,74. For the USA there is no information on phenotype data on IR Mapper, but resistance to pyrethroids has been reported in several states75,76,77.

Publicly available phenotype data for Ae. aegypti showing the proportion of records that report resistance, possible resistance and susceptibility. Numbers denote total number of records for the insecticide class for that country region44. Only data collected on Aedes aegypti after 2000 were included for countries that were present in the WGS data set.

In Africa, 53% of samples from Burkina Faso had more than two insecticide resistance mutations, all in the vgsc gene. Burkina Faso also had the highest reported resistance to pyrethroids when compared to the other African samples in this data set (Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, and Gabon). Levels of resistance to pyrethroids varied between the 8 countries analysed here. The highest levels of resistance were also observed in Brazil, Mexico, and Thailand, coinciding with samples with the most mutations in the vgsc gene (excluding the USA, where limited phenotypic data is available) (Figs. 3, 4).

The data from IR mapper showed that the largest number of reports of resistance involved insecticides of the organochlorine class. Mutations associated with this resistance include SNPs in the vgsc and rdl genes. However, countries with high resistance to organochlorines, such as Senegal and Nigeria have no or very low frequency of mutations in these loci. As the genomic data presented here do not have matching phenotypic information, it is possible that these samples were from a susceptible background or that there are other mechanism of resistance causing the observed phenotype. The least resistance was reported against organophosphates, although resistance is still high in Mexico, followed by Brazil and Thailand (Table 2). These countries only have 1 mutation, G12S, in the ace gene common across all of them.

Discussion

We explored the genetic diversity present in four genes (vgsc, ace-1, rdl and GSTe2) involved in insecticide response across 729 Ae. aegypti and 7 Ae. mascarensis samples from 15 countries. We identified many known and unreported amino-acid substitutions which may be involved in insecticide resistance. This catalogue of genetic variants is a valuable resource that can be explored to investigate molecular mechanism associated with insecticide resistance together with phenotypic information and used to design diagnostics genetic markers for molecular surveillance.

The populations with greater numbers of amino acid substitutions linked to insecticide resistance were Thailand (RDL: A301S; VGSC: V410L, S989P, V1016G and F1534C) and the USA (RDL A301S; VGSC: V410L, Gly923V, I1011M and F1534C). In Africa, the substitutions most frequently observed were RDL A301S and VGSC V410L and F1534C, but many countries had none of the reported mutations. We have also observed that VGSC V410L and S723T co-occur in all but one sample. None of the Thai samples had any mutations in the GSTe2 gene, despite having adequate read coverage. In other countries, we detected two common mutations in GSTe2 (C115F/S and L111S/F) in the DDT binding site. The C115F and C115S mutations were most frequent in Kenya (n = 142, n = 20), the USA (n = 114, n = 20) and Senegal (n = 82, n = 35). Previous work involving DDT docking with An. gambiae GSTe2 has suggested that one of the DDT’s planar p-chlorophenyl rings can fit into a sub-pocket, but the other ring faces spatial hindrance from M111 and F115 in the side chains69. In An. gambiae, the M111S substitution would require two nucleotide changes in contrast to one required for L111S/F in Ae. aegypti. To our knowledge, there are no reports of An. gambiae M111S or F115C/S; although the latter substitution requires a single amino acid change. These two substitutions were detected in almost all countries in this Aedes dataset.

We found only two mutations on the surface of the ACE1 pocket directly involved in hydrolysis (A81S, n = 5; D85H, n = 2)13. Since we did not have phenotype data, we cannot determine if these mutations are associated with resistance, but their low prevalence would appear at odds with much higher rate and multiple instances of emergence of G119S in An. gambiae20. Nevertheless, further functional work can contribute to elucidating the involvement of these mutations in resistance phenotypes.

We have also explored the possibility of gene duplications, and detected such variants in GSTe2 in USA, Mexico, Brazil, and Thailand, which are of interest due to the high rates of permethrin resistance reported in the Americas and Asia78,79. We found no duplications in west and central Africa or Eastern Kenya and South Africa regions6, but bioassay data in these regions is lacking. The possible duplication of the gene encoding VGSC is more puzzling. Previous research in D. melanogaster found that individuals lacking VGSC are not viable, but in contrast those with a single functioning gene copy are healthy apart from increased temperature sensitivity80. However, DDT and pyrethroids both prolong the open state of VGSC, so the extra gene copy is unlikely to induce resistance through increased number of pores14. Experimental work is required to explain the functional role of the extra copy and determine if it is associated with increased insecticide resistance. Long-read sequencing can help to validate the duplications detected and the differences between the vgsc sequences.

The inferred population structure was broadly consistent with previous research based on chromosomal loci. We even identified the two previously described distinct subpopulations of Ae. aegypti in Rabai District of Kenya60, but we also observed inconsistency between the structure we inferred from 15 non-resistance genes and 4 resistance genes (Fig. 1A,B). This inconsistency is very clear in case of VGSC where the same four mutations were present in 18/34 samples from Burkina Faso, 133/160 from USA and 8/15 from Mexico. While these could have arisen independently, single emergence and introduction elsewhere appears more parsimonious especially since these samples also share synonymous mutations. Such separate introductions of Ae. aegypti have been examined in the past38,62. However, the result may also be artefact of our methodology. The clustering methods we used have two shortcomings. First, they don’t have a measure of confidence; second, the relative distances between clusters and spread of points in cluster are usually not meaningful53. As a consequence, it’s impossible to infer diversity of population within a cluster, nor to determine relatedness between clusters.

An important observation for future research is that the cox1 gene and other mitochondrial loci may be problematic for population studies in Ae. aegypti because of the unknown number of cox1 copies per genome65,66. This is the result of unknown numbers of mitochondria per cell, unknown number of mitochondrial DNA copies on chromosomes, and unknown allelic diversity of all these cox1 sequences.

While we focused on exploring the genetic diversity in four genes associated with target site insecticide resistance, there are many loci that could have an important role, particularly in metabolic resistance. Multiple P450 genes, particularly members of the CYP6 and CYP9 subfamilies, have been associated with resistance by overexpression when comparing insecticide-resistant to susceptible strains81,82,83.

Having both phenotypic and genotypic data is fundamental for the full understanding of the link between phenotypic resistance and genetic mutations, as well as cross resistance mechanisms. Unfortunately, we did not have phenotypic data for all the countries with genotypic data in this study. We strongly advocate that where possible, phenotypic data be generated for samples with genomic sequences.

Further work on exploring genetic diversity in these gene families, particularly using long-read sequencing to support assembly and correct assignment of copy numbers to each individual gene, may reveal important molecular markers that can be involved in insecticide resistance. Genomic studies, like ours, can provide guidance to functional studies and inform the design of genotyping assays for large scale surveillance of insecticide resistance.

Data availability

All data in publicly available. Analysis scripts are available at https://github.com/AntonS-bio/resistance-AedesAegypti.

References

Lwande, O. W. et al. Globe-Trotting Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus: Risk Factors for Arbovirus Pandemics 71–81 (Mary Ann Liebert Inc., 2020).

Kraemer, M. U. G. et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. Albopictus. Elife 1, 1 (2015).

Brown, J. E. et al. Human impacts have shaped historical and recent evolution in Aedes aegypti, the dengue and yellow fever mosquito. Evolution. 68(2), 514–525 (2014).

Rocklöv, J. & Dubrow, R. Climate change: An enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat. Immunol. 21(5), 479–483 (2020).

Liu, N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: Impact. Mech. Res. Direct. 60, 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828 (2015).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 11(7), e0005625 (2017).

Ingham, V. A. et al. A sensory appendage protein protects malaria vectors from pyrethroids. Nature. 577(7790), 376–380 (2020).

Ingham, V. A., Wagstaff, S. & Ranson, H. Transcriptomic meta-signatures identified in Anopheles gambiae populations reveal previously undetected insecticide resistance mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 1 (2018).

Messenger, L. A. et al. A whole transcriptomic approach provides novel insights into the molecular basis of organophosphate and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Ethiopia. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 139, 1 (2021).

Balabanidou, V. et al. Cytochrome P450 associated with insecticide resistance catalyzes cuticular hydrocarbon production in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113(33), 9268–9273 (2016).

Du, Y., Nomura, Y., Zhorov, B. S. & Dong, K. Sodium channel mutations and pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti. Insects. 7(4), 1 (2016).

Pavlidi, N., Vontas, J. & Van Leeuwen, T. The role of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in insecticide resistance in crop pests and disease vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 27, 97–102 (2018).

Cheung, J., Mahmood, A., Kalathur, R., Liu, L. & Carlier, P. R. Structure of the G119S mutant acetylcholinesterase of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae reveals basis of insecticide resistance. Structure. 26(1), 130 (2018).

Field, L. M., Emyr Davies, T. G., O’Reilly, A. O., Williamson, M. S. & Wallace, B. A. Voltage-gated sodium channels as targets for pyrethroid insecticides. Eur. Biophys. J. 46(7), 675 (2017).

Scott, J. G. Life and death at the voltage-sensitive sodium channel: Evolution in response to insecticide use. 64, 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118-112420 (2019).

Kasai, S. et al. Discovery of super–insecticide-resistant dengue mosquitoes in Asia: Threats of concomitant knockdown resistance mutations. Sci. Adv. 8(51), 1 (2022).

Brengues, C. et al. Pyrethroid and DDT cross-resistance in Aedes aegypti is correlated with novel mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene. Med. Vet. Entomol. 17(1), 87–94 (2003).

Chung, H. H. et al. Voltage-gated sodium channel intron polymorphism and four mutations comprise six haplotypes in an Aedes aegypti population in Taiwan. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 13(3), 1 (2019).

Fan, Y. et al. Evidence for both sequential mutations and recombination in the evolution of kdr alleles in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 14(4), 1–22 (2020).

Weill, M. et al. Insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors. Nature 423(6936), 136–137 (2003).

Feyereisen, R., Dermauw, W. & Van Leeuwen, T. Genotype to phenotype, the molecular and physiological dimensions of resistance in arthropods. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 121, 61–77 (2015).

Engdahl, C. et al. Acetylcholinesterases from the disease vectors Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae: Functional characterization and comparisons with vertebrate orthologues. PLOS ONE. 10(10), e0138598 (2015).

Bloomquist, J. R. Toxicology, mode of action and target site-mediated resistance to insecticides acting on chloride channels. Compar. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 106(2), 301–314 (1993).

Ffrench-Constant, R. H., Williamson, M. S., Davies, T. G. E. & Bass, C. Ion channels as insecticide targets. J. Neurogenet. 30(3–4), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167706320161229781 (2016).

Fonseca-González, I., Quiñones, M. L., Lenhart, A. & Brogdon, W. G. Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti (L.) from Colombia. Pest Manag. Sci. 67(4), 430–437 (2011).

Goindin, D. et al. Levels of insecticide resistance to deltamethrin, malathion, and temephos, and associated mechanisms in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes from the Guadeloupe and Saint Martin islands (French West Indies). Infect. Dis. Poverty. 6(1), 1 (2017).

Grau-Bové, X. et al. Evolution of the insecticide target Rdl in African anopheles is driven by interspecific and interkaryotypic introgression. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37(10), 2900–2917 (2020).

Mintz, J. A. Two cheers for global POPs: A summary and assessment of the Stockholm convention on persistent organic pollutants. Georgetown Int. Environ. Law Rev. 14, 1 (2001).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Identification and distribution of a GABA receptor mutation conferring dieldrin resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41(7), 484–491 (2011).

Yang, C., Huang, Z., Li, M., Feng, X. & Qiu, X. RDL mutations predict multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles sinensis in Guangxi, China. Malar. J. 16(1), 1 (2017).

Lumjuan, N. et al. The role of the Aedes aegypti Epsilon glutathione transferases in conferring resistance to DDT and pyrethroid insecticides. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41(3), 203–209 (2011).

Matthews, B. J. et al. Improved reference genome of Aedes aegypti informs arbovirus vector control. Nature. 563(7732), 501–507 (2018).

Ortelli, F., Rossiter, L. C., Vontas, J., Ranson, H. & Hemingway, J. Heterologous expression of four glutathione transferase genes genetically linked to a major insecticide-resistance locus from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Biochem. J. 373(Pt 3), 957–963 (2003).

Riveron, J. M. et al. A single mutation in the GSTe2 gene allows tracking of metabolically based insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector. Genome Biol. 15(2), R27 (2014).

Mitchell, S. N. et al. Metabolic and target-site mechanisms combine to confer strong DDT resistance in Anopheles gambiae. PloS One. 9(3), 1 (2014).

Helvecio, E. et al. Polymorphisms in GSTE2 is associated with temephos resistance in Aedes aegypti. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 165, 1 (2020).

Crava, C. M. et al. Population genomics in the arboviral vector Aedes aegypti reveals the genomic architecture and evolution of endogenous viral elements. Mol. Ecol. 1, 1 (2021).

Rose, N. H. et al. Climate and urbanization drive mosquito preference for humans. Curr. Biol. 1, 1 (2020).

Lee, Y. et al. Genome-wide divergence among invasive populations of Aedes aegypti in California. BMC Genom. 20(1), 1–10 (2019).

Kelly, E. T. et al. Evidence of local extinction and reintroduction of Aedes aegypti in exeter California. Front. Trop. Dis. 2, 703873 (2021).

Faucon, F. et al. Identifying genomic changes associated with insecticide resistance in the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti by deep targeted sequencing. Genome Res. 25(9), 1347–1359 (2015).

Leong, C. S. et al. Enzymatic and molecular characterization of insecticide resistance mechanisms in field populations of Aedes aegypti from Selangor Malaysia. Parasites Vectors. 12(1), 1–17 (2019).

Poupardin, R., Srisukontarat, W., Yunta, C. & Ranson, H. Identification of carboxylesterase genes implicated in temephos resistance in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 8(3), 1 (2014).

Knox, T. B. et al. An online tool for mapping insecticide resistance in major Anopheles vectors of human malaria parasites and review of resistance status for the Afrotropical region. Parasites Vectors. 7(1), 1–14 (2014).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9(4), 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25(16), 2078–2079 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20(9), 1297–1303 (2010).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 10(2), 1 (2021).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 6(2), 80–92 (2012).

Boratyn, G. M. et al. Domain enhanced lookup time accelerated BLAST. Biol. Direct. 1, 1 (2012).

McInnes, L., Healy, J., & Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv (2018).

Campello, R. J. G. B., Moulavi, D. & Sander, J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. Lecture Notes Comput. Sci. 7819(2), 160–172 (2013).

Diaz-Papkovich, A., Anderson-Trocmé, L. & Gravel, S. A review of UMAP in population genetics. J. Hum. Genet. 66(1), 85–91 (2021).

Becht, E. et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(1), 38–47 (2018).

Bellin, N. et al. Unsupervised machine learning and geometric morphometrics as tools for the identification of inter and intraspecific variations in the Anopheles Maculipennis complex. Acta Tropica. 233, 106585 (2022).

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv. 1, 1 (2021).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 596(7873), 583–589 (2021).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 235–242 (2000).

Tatusova, T. et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(14), 6614–6624 (2016).

Gloria-Soria, A. et al. Global genetic diversity of Aedes aegypti. Mol. Ecol. 25(21), 5377–5395 (2016).

Kotsakiozi, P. et al. Population structure of a vector of human diseases: Aedes aegypti in its ancestral range Africa. Ecol. Evol. 8(16), 7835–7848 (2018).

Pless, E. et al. Multiple introductions of the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti, into California. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11(8), e0005718 (2017).

Soghigian, J. et al. Genetic evidence for the origin of Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito, in the southwestern Indian Ocean. Mol. Ecol. 29(19), 3593–3606 (2020).

McBride, C. S. et al. Evolution of mosquito preference for humans linked to an odorant receptor. Nature 515(7526), 222–227 (2014).

Richly, E. & Leister, D. NUMTs in sequenced eukaryotic genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21(6), 1081–1084 (2004).

Black Iv, W. C. & Bernhardt, S. A. Abundant nuclear copies of mitochondrial origin (NUMTs) in the Aedes aegypti genome. Insect Mol. Biol. 18(6), 705–713 (2009).

Clarkson, C. S. et al. Genome variation and population structure among 1142 mosquitoes of the African malaria vector species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Genome Res. 30(10), 1533–1546 (2020).

Colletier, J. P. et al. Structural insights into substrate traffic and inhibition in acetylcholinesterase. EMBO J. 25(12), 2746–2756 (2006).

Wang, Y. et al. Structure of an insect epsilon class glutathione S-transferase from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae provides an explanation for the high DDT-detoxifying activity. J. Struct. Biol. 164(2), 228–235 (2008).

Chen, C. et al. Marker-assisted mapping enables forward genetic analysis in Aedes aegypti, an arboviral vector with vast recombination deserts. Genetics. 222(3), 1 (2022).

Hamid, P. H., Prastowo, J., Widyasari, A., Taubert, A. & Hermosilla, C. Knockdown resistance (kdr) of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Aedes aegypti population in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia. Parasites Vectors. 10(1), 1 (2017).

Rasli, R. et al. Susceptibility status and resistance mechanisms in permethrin-selected, laboratory susceptible and field-collected Aedes aegypti from Malaysia. Insects 9(2), 43 (2018).

Saha, P. et al. Prevalence of kdr mutations and insecticide susceptibility among natural population of Aedes aegypti in West Bengal. PLOS ONE. 14(4), e0215541 (2019).

Mano, C. et al. Protein expression in female salivary glands of pyrethroid-susceptible and resistant strains of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors. 12(1), 1–19 (2019).

Yang, F. et al. Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in California by biochemical assays. J. Med. Entomol. 57(4), 1176 (2020).

Kandel, Y. et al. Widespread insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti L. from New Mexico, USA. PLOS ONE. 14(2), e0212693 (2019).

Hernandez, H. M., Martinez, F. A. & Vitek, C. J. Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti Varies seasonally and geographically in Texas/Mexico border cities. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 38(1), 59–69 (2022).

Chuaycharoensuk, T. et al. Frequency of pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand. J. Vector Ecol. 36(1), 204–212 (2011).

Solis-Santoyo, F. et al. Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti from Tapachula, Mexico: Spatial variation and response to historical insecticide use. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 15(9), 1 (2021).

Ravenscroft, T. A. et al. Drosophila voltage-gated sodium channels are only expressed in active neurons and are localized to distal axonal initial segment-like domains. J. Neurosci. 40(42), 7999–8024 (2020).

Vontas, J., Katsavou, E. & Mavridis, K. Cytochrome P450-based metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles and Aedes mosquito vectors: Muddying the waters. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 170, 104666 (2020).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Cis-regulatory CYP6P9b P450 variants associated with loss of insecticide-treated bed net efficacy against Anopheles funestus. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 1–11 (2019).

Weedall, G. D. et al. A cytochrome P450 allele confers pyrethroid resistance on a major African malaria vector, reducing insecticide-treated bednet efficacy. Sci. Transl. Med. 11(484), 7386 (2019).

Acknowledgements

E.L.C. is funded by an MRC LID PhD studentship TGC and SC are funded by UKRI grants (BBSRC BB/X018156/1; MRC MR/X005895/1; EPSRC EP/Y018842/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, SC and TC designed the study. AS and EC analysed the data under the supervision of TC and SC. All authors interpreted the results. AS and EC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spadar, A., Collins, E., Messenger, L.A. et al. Uncovering the genetic diversity in Aedes aegypti insecticide resistance genes through global comparative genomics. Sci Rep 14, 13447 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64007-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64007-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti: genetic mechanisms worldwide, and recommendations for effective vector control

Parasites & Vectors (2025)

-

Global distribution and impact of knockdown resistance mutations in Aedes aegypti on pyrethroid resistance

Parasites & Vectors (2025)

-

Population genetic diversity and natural Wolbachia infection in Aedes aegypti from Pakistan

Parasites & Vectors (2025)

-

Genome-wide analysis of genetic diversity in Anopheles darlingi from Rondônia State, Brazil

Communications Biology (2025)

-

Mating of unfed, engorged, and partially to fully gravid Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) female mosquitoes in producing viable eggs

Parasites & Vectors (2024)