Abstract

This study investigates the potential of platinum (Pt) decorated single-layer WSe2 (Pt-WSe2) monolayers as high-performance gas sensors for NO2, CO2, SO2, and H2 using first-principles calculations. We quantify the impact of Pt placement (basal plane vs. vertical edge) on WSe2’s electronic properties, focusing on changes in bandgap (ΔEg). Pt decoration significantly alters the bandgap, with vertical edge sites (TV-WSe2) exhibiting a drastic reduction (0.062 eV) compared to pristine WSe2 and basal plane decorated structures (TBH: 0.720 eV, TBM: 1.237 eV). This substantial ΔEg reduction in TV-WSe2 suggests a potential enhancement in sensor response. Furthermore, TV-WSe2 displays the strongest binding capacity for all target gases due to a Pt-induced “spillover effect” that elongates adsorbed molecules. Specifically, TV-WSe2 exhibits adsorption energies of − 0.5243 eV (NO2), − 0.5777 eV (CO2), − 0.8391 eV (SO2), and − 0.1261 eV (H2), indicating its enhanced sensitivity. Notably, H2 adsorption on TV-WSe2 shows the highest conductivity modulation, suggesting exceptional H2 sensing capabilities. These findings demonstrate that Pt decoration, particularly along WSe2 vertical edges, significantly enhances gas sensing performance. This paves the way for Pt-WSe2 monolayers as highly selective and sensitive gas sensors for various applications, including environmental monitoring, leak detection, and breath analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gas sensors play a crucial role across various domains, contributing to air quality, climate change mitigation, industrial safety, and medical diagnostics1,2. The development of sensors for NO23,4, CO25,6, SO27,8, and H29,10 is imperative due to their significant impact on human health, the environment, and industrial processes. NO2, a major air pollutant, contributes to respiratory issues and environmental degradation11. CO2 levels serve as critical indicators of indoor air quality and are linked to climate change12. SO2, an industrial byproduct, is associated with air pollution and respiratory ailments13. H2, widely used in industrial processes, poses safety risks in certain concentrations14. Efficient gas sensors for these compounds are essential for real-time monitoring, early hazard detection, and proactive measures to ensure environmental sustainability and public health.

Highly sensitive and selective sensors are crucial for the swift and accurate detection of hazardous gases to minimize risks. Various sensors have been developed to address these challenges. Conventional gas sensors, relying on metal oxides and polymers, face limitations such as reduced selectivity, high operating temperatures, extended response and recovery times, limited sensitivity to low concentrations, and vulnerability to environmental conditions15,16. Following the success of utilizing graphene as a gas sensor17,18, researchers have shifted their focus to exploring two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) materials19,20. These materials, with exceptional structural configurations, offer large surface-to-volume ratios and the ability to alter their electronic properties21,22. The interest in 2D materials is driven by their potential to enhance gas sensing capabilities, enabling more accurate and selective detection of various gases.

Recent reports highlight tungsten diselenide (WSe2) as a superior gas sensor material among TMDs. WSe2 exhibits enhanced sensitivity, tunable bandgap for specific gas detection, and efficient charge transport, providing swift and precise responses23,24. Its larger surface area and chemical stability contribute to improved adsorption and durability, while low noise levels and selective customization enhance accuracy. WSe2’s compatibility with microfabrication enables compact devices and effective room-temperature operation. Ongoing research, exemplified by Guo et al.25, showcases WSe2 nanosheets with high sensitivity to NO2 at room temperature, high selectivity, and stability for 8 weeks. Similarly, Wu et al.26 demonstrate a WSe2 monolayer-based NO2 gas sensor with detection capabilities across varying concentrations and temperatures, emphasizing rapid recovery, high selectivity, reversibility, and stability over 60 days for NO2 detection.

The use of 2D materials, especially TMDs like WSe2, in gas sensors is gaining attention for their superior performance attributed to a high surface-to-volume ratio27. Monolayers of WSe2, a significant member of dichalcogenides, exhibit remarkable electronic properties and substantial surface area, enhancing the sensitivity and range of gas sensors with specific doping or surface modifications. This is crucial for devices detecting harmful gases (NO2, HCHO, NH3, SF6 decomposed gases) in residential and occupational environments28. Noble metal-decorated WSe2 is recognized as a promising material for gas sensing applications. Pt atoms are a frequent choice for absorbing molecules on TMDs due to several key properties. Pt’s well-known catalytic activity aids in weakening bonds and facilitating desired chemical reactions on the TMD surface. It can also modify the TMD’s work function, influencing the adsorption and release of specific gas molecules for targeted sensing or manipulation. Additionally, Pt offers good thermal and chemical stability, making it practical for applications where the TMD-Pt composite might encounter harsh environments. Compared to generic metal decoration, Pt provides a more targeted approach due to its specific catalytic properties and work function effects. Furthermore, Pt can influence the TMD’s electronic structure at the interface, potentially enhancing its conductivity. The combination of Pt and the TMD can even create synergistic effects, leading to superior performance compared to either material alone. Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations play a crucial role in examining gas sensing and functionalization of single-atom catalysts, revealing improved sensitivity of Pd-functionalized WSe2 systems in detecting harmful gases. Doping WSe2 with noble metals (Pd, Ag, Au, Pt) enhances gas sensing, with Ag-WSe2 showing potential for efficient NO2 sensing29. Noble metal catalysts like Pt/Pd are proposed to boost H2 gas sensor sensitivity at room temperature. Studies indicate that Pd film on TiO2 enhances H2 sensitivity30, while Pt nanoparticles in F-MWCNT/TiO2/Pt hybrid achieve notable sensitivity to H2 molecules at specific concentrations31.

Comprehending the importance of further theoretical and experimental exploration in understanding and optimizing the gas sensing capabilities of single-atom Pt-decorated WSe2 (Pt-WSe2). While significant progress has been made in comprehending the effects of single-atom doping, especially in materials like molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), there remains a notable gap in theoretical inquiries regarding the adsorption phenomena of representative gases (H2, NO2, CO2, and SO2) on monolayers of Pt-WSe2. The research aims to address this gap by investigating the interactions between these target gas molecules and WSe2 layers coated with single-atom Pt, providing valuable insights for gas sensing applications. Consequently, this methodology integrates the distinctive characteristics of WSe2, including its elevated surface-to-volume ratio and semiconducting nature, with the catalytic attributes of Pt, leading to an enhanced gas sensing platform with improved efficiency. Gas sensing has advanced significantly as a result of the combination of these materials and methods.

This study employs DFT to investigate the gas sensing capabilities of a Pt-WSe2-based system toward specific target gases (H2, NO2, CO2, and SO2). Pt-atom is strategically decorated over the basal and vertical edges of the WSe2 monolayer. The analysis encompasses electronic characteristics, including band structure, density of states (DOS), charge density difference (CDD), and population analysis for different gases. The vertical configuration of Pt-WSe2 demonstrates outstanding sensitivity and recovery time for H2, attributed to the spillover effect. The findings propose a promising strategy to enhance the sensing response to hydrogen gas, elucidating the impact of Pt functionalization on the sensing mechanism.

Computational methods

This paper employs the Dmol3 package in Material Studio software for all theoretical and DFT calculations32,33. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE) generalized approximation is utilized to handle electron exchange correlation accurately34,35. The study incorporates Density Functional Theory with dispersion (DFT-D) and van der Waals (vdWs) interactions to enhance accuracy, addressing the traditional DFT’s challenges in capturing weak forces36,37. Tkatchenko and Scheffler’s (TS) method is applied for precise simulation of vdWs interactions38,39. DFT semi-core pseudopotentials (DSPP) replace core electrons of specific atoms, enhancing accuracy in electronic interaction descriptions40. DSPP, combined with Double numerical plus polarization (DNP) basis sets, is used to describe electronic wavefunctions, improving predictions of molecular properties and behaviour. The approach involves two sets of functions for core and valence electrons, including extra functions for electron density changes due to neighbouring atoms (polarization). This comprehensive methodology enhances accuracy in describing electronic interactions and predictions of molecular behaviour. In geometry optimizations, the criteria for energy convergence, maximum force, and maximum displacement were set at 1.0 × 10–5 Ha, 0.002 Ha/Å, and 0.005 Å, respectively. A global orbital cutoff radius of 5.0 Angstroms was used. For calculating DOS, a 7 × 7 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid was employed, while a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid was utilized for other calculations, ensuring an accurate representation of the Brillouin zone41. The WSe2 structure was cleaved along the [1 0 0] direction to expose the vertical edge. Moreover, for the analysis, we have considered a 3 × 3 × 1 WSe2 supercell with a vacuum region of c = 15 Å in order to avoid contact with surrounding WSe2 layers. Furthermore, the study involves calculating adsorption energy (Ead) using Eq. (1), respectively. The CDD for the adsorption configuration (Δρ) is determined using Eq. (2). (Refer to Eqs. (1), (2) in the supporting information). Moreover, in physisorption, the dominant interactions between the adsorbate and adsorbent are typically weak, characterized by van der Waals forces or dipole–dipole interactions. This is reflected in the observation that the sum of covalent radii tends to exceed the adsorption distance. Conversely, chemisorption involves stronger interactions, often leading to the formation of chemical bonds between the adsorbate and adsorbent surface. Here, the adsorption distance closely aligns with the sum of covalent radii, indicating the potential for chemical bond formation. This interpretation is substantiated by previous studies utilizing density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which have consistently demonstrated this correlation42,43.

Results and discussion

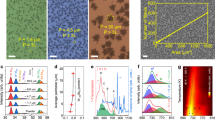

To examine the gas sensing behaviour of WSe2, firstly we examine the physical and electrical properties of individual monolayer structures of WSe2 as shown in Fig. 1a, focusing on its geometric structure. The available chalcogen vacancies play a significant role in the electronic configuration of TMDs44. Subsequently, we investigate the properties of Pt-coated WSe2. In this study, we specifically consider WSe2 with a monolayer structure, where cutting the (001) plane results in the formation of hexagonal lattices with a honeycomb-like arrangement. Following structural optimization, the monolayers of WSe2 displayed a bond length of 2.555 Å between W and Se atoms, and a bond length of 3.380 Å between the Se atoms (Fig. 1b). The calculated outcomes and the reported values of 2.54 Å (W-Se) exhibited a notable concordance, indicating a satisfactory agreement between them45. Moreover, in Fig. 1c we showed the bandgap for the WSe2 monolayer which shows the value of 1.576 eV between the conduction and valence band representing good agreement with previously reported work46. Figure 1d presents the projected density of states (PDOS) for the pristine WSe2 monolayer. The PDOS reveals significant hybridization between the W 4d orbitals and the Se 4s and 4p orbitals, indicating the formation of covalent bonds between the W and Se atoms.

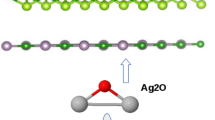

This study employs computational simulations to investigate the impact of Pt decoration on the electronic properties of a WSe2 monolayer. Moreover, we considered three potential sites for decoration and they are labelled as TBH-WSe2 (Pt-atom decorated over the hallow hexagonal site in WSe2 basal plane configuration), TBM-WSe2 (Pt-atom decorated over the W atom in WSe2 basal plane configuration), and TV-WSe2 (Pt-atom decorated at the vertical edge of WSe2) as illustrated in Fig. 2a–c.

Furthermore, the optimized configurations of TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 reveal bandgap and DOS values of 0.720 eV, 1.237 eV, and 0.062 eV, respectively (Figs. S1–S3). We have analyzed the electronic spin for Pt-WSe2 (Fig. S11(a1–a3) in Supplementary Information for details). Pt functionalization on the WSe2 monolayer induces the hybridization of electronic orbitals, creating new states within the bandgap and reducing bandgap values. The Pt placement significantly influences the electronic properties of WSe2, highlighting potential functionality tailoring. Adsorption energy is negative, indicating an exothermic process. Bond lengths vary slightly post-optimization, with bond lengths between Pt-atom and W-atom for TBH-WSe2 and TV-WSe2 at 3.917 Å and 2.802 Å, respectively, and Pt and Se atom bond lengths in TBM-WSe2 at 2.429 Å. Mulliken and Hirshfeld analyses show electron depletion at Pt, indicating positive charges (0.050 e, 0.056 e, 0.062 e) in TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2, respectively (Fig. S4). Previous studies suggest that Pt-atom promotes catalytic oxidation, leading to hole accumulation layers. Rosy and green colours in Fig. S4 represent electron depletion and accumulation, respectively. The thermodynamic stability of TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 combinations was evaluated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations performed at 500 K to examine their thermal stability. Moreover, phonon dispersion simulations were conducted to analyze the vibrational modes of TV-WSe2, as shown in Fig. S5. Additionally, the optimized arrangement of target gases is depicted in Fig. S6.

H2 adsorption

Figure 3 depicts the stable adsorption and CDD of the H2 gas molecule for all three proposed structures namely TBH-WSe2 (Fig. 3a), TBM-WSe2 (Fig. 3b), and TV-WSe2 (Fig. 3c). It can be observed that there is elongation in the H–H bond (~ 0.212 Å) which denotes the dissociation of the H2 molecule and supports the spillover effect47 due to the decoration of Pt. The enhanced H2 detection capabilities of Pt-WSe2 arise primarily from two contributing factors: the presence of Pt-atom and the interfacial contact between Pt and WSe2. Pt-atom acts as a potential candidate for efficient H2 sensing, facilitating the “spillover effect” where captured H2 molecules migrate to the WSe2 surface for subsequent adsorption. Moreover, the contact between Pt and WSe2 promotes the generation of new adsorption sites on the WSe2 monolayer, further enhancing the overall H2 binding capacity. Therefore, both the Pt-atom and the synergistic Pt-WSe2 interface play crucial roles in the superior H2 detection performance of Pt-WSe2. In the Pt-WSe2 system, upon interaction with H2 gas molecules, an initial adhesion occurs between the catalytic Pt-atom and the gas molecules, leading to subsequent dissociation into single hydrogen atoms. This establishes the conditions necessary for a chemical interaction to occur between H atoms and the WSe2 material, hence promoting the process of H atom diffusion into the WSe2 structure. This causes chemisorption among all three proposed configurations. Moreover, a reduction in electrical resistance when H2 comes in contact with the Pt-WSe2 sensor. The observed decrease in resistance implies that H2 tends to transfer electrons to the WSe2 material. In other words, H2 is a reducing nature gas due to which it will donate electrons to the system which is confirmed with the help of Mulliken and Hirshfeld’s analysis and the gap between Pt and H atom shown in Table 1.

Most stable configuration and corresponding charge density distribution (CDD) following H2 adsorption at three different sites where a Pt is decorated: (a) the hollow site in the basal configuration, (b) above the W atom in the basal configuration, and (c) along the vertical edge of WSe2. In the CDD diagram, electron depletion manifests itself in a rosy colour, while electron accumulation is represented by a green colour.

Consequently, it can be observed from Table 1 total charge over the H2 molecule is positive which displays the depletion of electrons. And these electrons are transmitted to the Pt-atom which possesses a negative value which is also illustrated in the CDD diagram. Furthermore, we have provided the electronic structure analysis (i.e., band structure, DOS, and PDOS) after the adsorption of the H2 gas molecule in the supplementary information (Fig. S7). We investigated the electronic spin response upon H2 adsorption (Fig. S11(b1–b3); refer to Supplementary Information for details). In addition, we have calculated the adsorption energies for the TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 configurations towards the H2 gas molecule and obtained the values of − 0.0293 eV, − 0.0788 eV, and − 0.1261 eV, respectively. It could be easily seen that the most favourable case for strong H2 adsorption was exhibited by TV-WSe2.

NO2 adsorption

The Fig. 4 illustrates the stable adsorption and CDD of the NO2 gas molecule on three suggested structures: TBH-WSe2 (Fig. 4a), TBM-WSe2 (Fig. 4b), and TV-WSe2 (Fig. 4c). Notably, there is an elongation observed in the N–O bond, approximately to 0.060 Å, indicating the weak interaction between the Pt-atom and the NO2 molecule. Furthermore, this minor extension in bond is corroborated by the low binding capacity arising from the Pt decoration.

Optimal arrangement and associated charge density distribution after NO2 adsorption at three distinct locations where a Pt is functionalized: (a) the hollow site in the basal configuration, (b) positioned above the W atom in the basal configuration, and (c) situated along the vertical edge of WSe2. Electron depletion and accumulation are visualized through the application of rosy and green colours.

The Pt–N minimum adsorption distance, measuring 2.367 Å, surpasses the sum of relevant covalent radii (2.010 Å for Pt–N48), indicating a physisorption nature. It is evident that physisorption was consistently observed for NO2 in all three suggested arrangements. Additionally, it is essential to note that NO2 gas exhibits an oxidizing nature, causing it to withdraw electrons from the system. This aspect has been confirmed through the comprehensive analysis performed using Mulliken and Hirshfeld’s population analysis method, and the findings are presented in Table 2 with the adsorption length between Pt and O atom.

As a result, Table 2 reveals that the total charge on the NO2 molecule is negative, signifying the accumulation of electrons within the molecule. These electrons are then extracted from the Pt-atom, which, as shown in the CDD diagram, possesses a negative value. Additionally, electronic structure analysis, including band structure, DOS, and PDOS after NO2 gas molecule adsorption, is available in the supplementary information (Fig. S8). To understand the interaction between the material and NO2 on a deeper level, we analyzed the electronic spin after gas adsorption as shown in Fig. S11(c1–c3) (see Supplementary Information for details). Additionally, we have conducted calculations for the adsorption energy of the TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 configurations upon exposure to NO2 gas molecules. The obtained values are − 0.4227 eV, − 0.3879 eV, and − 0.5243 eV, respectively. Notably, the most favourable scenario for moderate adsorption is observed in the case of TV-WSe2, signifying enhanced physisorption. The stronger adsorption energy of the TV-WSe2 system among all the proposed structures confirms more available W sites which enhance the adsorption towards the NO2 gas molecule49. Overall, in this case, the Pt-atom facilitates the weak vdW interaction force for the NO2 gas molecule.

CO2 adsorption

In Fig. 5, we can observe the stable adsorption and dissociation of the CO2 gas molecule on three suggested structures: TBH-WSe2 (Fig. 5a), TBM-WSe2 (Fig. 5b), and TV-WSe2 (Fig. 5c). Significantly, the C–O bond exhibits an alteration of approximately 0.074 Å, indicating a weak vdW interaction between CO2 and Pt. Additionally, noticeable deformations are observed in the CO2 structure when it interacts with TBH-WSe2 and TBM-WSe2. This deformation is a result of an enhanced adsorption energy (~ − 0.50 eV) and less adsorption distance in comparison to the TV-WSe2-based configuration. In TBH-WSe2 and TBM-WSe2, the Pt-atom interacts with the C atom, exhibiting adsorption distances of 2.012 Å and 2.138 Å, respectively. For TBH-WSe2 and TBM-WSe2 the adsorption distance is below and above the sum of relevant covalent radii (2.050 Å for Pt and C48), indicative of chemisorption and physisorption, respectively. Conversely, in TV-WSe2, the Pt-atom interacts with the O atom, with an adsorption distance of 3.416 Å exceeding the sum of relevant covalent radii (2.020 Å for Pt and O48), suggesting a physisorption mechanism. These findings, supported by the CDD diagram (Fig. 5), elucidate distinct adsorption behaviours in the investigated Pt-WSe2 variants. Consequently, based on these observations, it can be concluded that chemisorption takes place in the case of TBH-WSe2, while physisorption occurs in the case of TBM-WSe2 and TV-WSe2 structures. Moreover, it is crucial to highlight that the CO2 gas demonstrates an oxidizing characteristic, thereby extracting electrons from the system. To confirm this aspect, we conducted a comprehensive analysis using Mulliken and Hirshfeld’s population analysis method, and the adsorption length is tabulated in Table 3.

Most stable configuration and corresponding charge density distribution following CO2 adsorption at three different sites where a Pt is decorated: (a) the hollow site in the basal configuration, (b) above the W atom in the basal configuration, and (c) along the vertical edge of WSe2. Electron depletion and electron accumulation are mapped onto rosy and green colour regions, respectively.

Table 3 presents intriguing findings, indicating a negative total charge on the CO2 molecule, suggesting an accumulation of electron density over the CO2 molecule. These electrons appear to be extracted from the Pt-atom, as evidenced by the negative value displayed in the CDD diagram. The impact of CO2 adsorption on the electronic structure (band structure, DOS, and PDOS) and electronic spin is presented in the supplementary information (Figs. S9, S11(d1–d3)). Furthermore, we performed calculations for the adsorption energies of the CO2 gas molecule on TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 configurations, resulting in values of − 0.5577 eV, − 0.5373 eV, and − 0.5777 eV, respectively. As it can be observed that there is slight deformation in the CO2 configuration after the optimization (for TBH-WSe2 and TBM-WSe2), due to the stronger adsorption energy and less adsorption distance.

SO2 adsorption

The adsorption configuration of the SO2 gas molecule is similar to the CO2 and NO2 gas molecules for the TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 as shown in Fig. 6a–c. In addition, there is a variation in S–O bond length (~ 0.036 Å) after adsorption as it can be seen in the CDD diagram. This variation is due to the stronger adsorption energy of these structures as aforementioned. Consequently, it implies that there is weak vdW interaction exhibited between Pt-atom and SO2 molecule. In TBM-WSe2, the Pt-atom interacts with the S atom, with an adsorption distance of 2.608 Å, exceeding the sum of relevant covalent radii (2.410 Å for Pt and S48). Conversely, in TBH-WSe2 and TV-WSe2, the Pt-atom interacts with the O atom, exhibiting adsorption distances of 2.355 Å and 2.320 Å, respectively, surpassing the sum of relevant covalent radii (2.020 Å for Pt and O48). The consistent observation across all three configurations reveals that the adsorption distances are greater than the sum of relevant covalent radii, indicating a physisorption mechanism, as corroborated by the CDD diagram (Fig. 6). Additionally, it is essential to emphasize that SO2 gas exhibits an oxidizing nature, resulting in the withdrawal of electrons from the system. To validate this phenomenon, we conducted an extensive analysis using Mulliken and Hirshfeld’s population analysis method, and the adsorption length data are presented in Table 4.

Optimal arrangement and associated charge density distribution after SO2 adsorption at three distinct locations where a Pt is functionalized: (a) the hollow site in the basal configuration, (b) positioned above the W atom in the basal configuration, and (c) situated along the vertical edge of WSe2. Electron depletion and accumulation are represented by the colour spectrum, with rosy signifying depletion and green signifying accumulation.

The findings from Table 4 revealed a negative total charge on the SO2 molecule, which implies the electron accumulation within the SO2 molecule. These electrons seem to be drawn from the Pt-atom, as evidenced by the negative value shown in the CDD diagram. Further details regarding the electronic structure analysis (including band structure, DOS, and PDOS) and electronic spin upon SO2 gas molecule adsorption can be found in the supplementary information (Figs. S10, S11(e1–e3)). Moreover, we obtained the adsorption energy of SO2 gas molecules to be − 0.6813 eV, − 0.7511 eV, and − 0.8391 eV for TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2, respectively. The most promising results of TV-WSe2, which suggests a potent physisorption action, are particularly remarkable.

Sensing mechanism

To interpret the sensing mechanism of Pt-WSe2 composites, we examined the molecular interaction and charge transfer at the interface. It can be observed that the adsorption energy (as mentioned in Table S1) is improved in TV-WSe2 configuration among all proposed structures indicating strong interaction between the target gas molecule and Pt. A negative adsorption energy value signifies that the adsorption process releases heat, making it exothermic. Moreover, the adsorption energy (Fig. 7a) value is also listed in Table S1. (Refer to Table S1 in the supporting information).

Moreover, to confirm the response of H2 due to higher binding capacity we have calculated the sensitivity. The electrical conductivity (\(\sigma\)) can be defined as50:

Here, e and µ represent carrier charge and mobility (constant because of monolayer), respectively. And n denotes the carrier concentration and it is defined as50:

where Eg represents the bandgap of the system. It can be seen that carrier concentration is dependent on the Eg. The sensitivity (S) is defined as a relative change in resistance51:

Using Eq. (3), the sensitivity can also be represented as:

Equation (4) shows the simplified equation of S where, \({E}_{{g}_{(Sys,Gas)}}\), and \({E}_{{g}_{(Sys,Isolated)}}\) represents the energy band gap of the system with and without gas adsorption, respectively. According to Eq. (4), the sensitivity value for distinct target gas molecules (H2, NO2, CO2, and SO2) adsorbed TBH-WSe2, TBM-WSe2, and TV-WSe2 systems is tabulated in Table 5.

Figure 7b–f represents the schematic of energy band structure and gas sensing mechanisms for TV-WSe2-based configuration towards NO2, CO2, SO2, and H2 gas molecule. As we can see from the energy band diagram when a Pt single atom functionalized over WSe2, there is a difference between the Fermi level of WSe2 and Pt i.e., work function (ϕ) of WSe2 is less than Pt due to which the electrons will transfer from WSe2 to Pt-atom until the Fermi levels of both the constituents (Pt and WSe2) lie at the equilibrium. During the adsorption of NO2, CO2 and SO2 molecules over Pt-WSe2 composite, gases will withdraw electrons due to their oxidizing nature. As it is also verified from the CDD, Mulliken, and Hirshfeld analysis as discussed in the aforementioned subsections. Upon NO2, CO2, and SO2 adsorption, there is a depletion of electrons over Pt due to which it possesses a positive value and accumulation of electrons over target gas molecule (NO2, CO2, and SO2) resulting in a negative value. Consequently, there is a depletion of charge carriers due to which the sensing material resistance gets modified. But, the H2 molecule has a reducing nature due to which it donates electrons to the sensing layer. This is also confirmed by the CDD, Mulliken, and Hirshfeld analysis. Upon H2 adsorption, there is the accumulation of electrons over Pt due to which it possesses a negative value, and depletion of electrons over H2 resulting in a positive value. As it can also be observed that there is elongation in the H–H bond after adsorption over Pt-WSe2 which confirms the spillover effect. As a result of this phenomenon, the H atom undergoes dissociation, leading to interactions with the WSe2 layer, ultimately resulting in an increase in sensitivity to H2 molecules. Furthermore, our computational results as mentioned in Table 5 affirm that the TV-WSe2 configuration exhibits higher sensitivity in the presence of H2 gas molecules. Moreover, we examine the ϕ(s) of pristine and Pt-decorated WSe2 monolayers under gas adsorption to comprehend their electron overflow behaviour. Figure S11 displays all of the systems’ computed ϕ values (see the Supplementary Information for details). Furthermore, to confirm sensing performance we employed the van’t-Hoff–Arrhenius expression shown in Eq. (5)42 and analyzed the recovery time (in s) which is presented in Table S1.

where A, kB, and T represent attempted frequency (~ 10–12 s−1)42, Boltzmann constant, and temperature, respectively. Ea denotes the potential barrier for desorption which is equivalent to adsorption energy. As it can be seen the recovery time for the TV-WSe2-based system to detect SO2 is maximum at low temperatures due to strong adsorption energy. Moreover, due to strong adsorption energy among all configurations, the adsorption and desorption are dependent on activation and deactivation energy, respectively. The deactivation energy depends on temperature hence the recovery time decreases with an increase in temperature. As it can be depicted in Table S1 all three proposed configurations have faster recovery time in the case of H2 gas molecules. In previous studies, it has been shown that the Pt loaded over 2D nanomaterial configuration is highly selective for the H2 gas molecule. And among these systems adsorption energy is comparatively stronger in the case of TV-WSe2-based H2 gas molecule as aforementioned in the result and discussion section. Upon H2 adsorption, there is an addition of energy states in the bandgap due to charge transport characteristics resulting in variation in the bandgap.

Conclusions

In this work, we have decorated Pt over the basal and vertical edge of WSe2 and performed the DFT study for the gas sensing towards distinct target gases (H2, NO2, CO2, and SO2) using the Dmol3 package in Material Studio software. We have analyzed the electronic characteristics (bandstructure, DOS, CDD, and population analysis) of Pt decorated over the WSe2 system with and without adsorption of target gases. We have analyzed recovery times for distinct combinations in which the H2 adsorbed system shows quicker recovery in contrast to others. The rates of adsorption and desorption are directly influenced by the respective activation and deactivation energies, which exhibit a strong dependence on temperature. Moreover, the introduction of Pt onto WSe2 induces a spillover effect, substantiated by the elongation of the target gas molecule. In the TV-WSe2 configuration, there is an increased presence of W edge sites, serving as additional adsorption sites for the gas molecule. Significantly, these W edge sites exhibit higher binding capacity and larger surface area contributing to an enhanced sensitivity in TV-WSe2 towards the target gas molecules. TV-WSe2 shows an excellent sensitivity for the H2 molecule. The adsorption of gas molecules onto the sensing material causes a modulation in electrical conductivity, arising from the interaction between the adsorbed gas molecule and the sensing layer. Our work shows that the decoration of Pt over the vertically oriented WSe2 enhances the sensing performance significantly.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Rab, S., Singh, R. P. & Suman, R. Sensors for daily life: A review. Sens. Int. 2, 100121 (2021).

Adam, T. & Gopinath, S. C. Nanosensors: Recent perspectives on attainments and future promise of downstream applications. Process Biochem. 117, 153–173 (2022).

Kushwaha, A. & Goel, N. Edge enriched MoS2 micro flowered structure for high performance NO2 sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 393, 134190 (2023).

Sowmya, B., John, A. & Panda, P. A review on metal-oxide based pn and nn heterostructured nano-materials for gas sensing applications. Sens. Int. 2, 100085 (2021).

Alaarage, W. K., Abo Nasria, A. H. & Abdulhussein, H. A. Computational analysis of CdS monolayer nanosheets for gas-sensing applications. Eur. Phys. J. B 96, 134 (2023).

Govind, A. et al. Highly sensitive near room temperature operable NO2 gas-sensor for enhanced selectivity via nanoporous CuO@ ZnO heterostructures. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110056 (2023).

Dimitrievska, I., Paunovic, P. & Grozdanov, A. Recent advancements in nano sensors for air and water pollution control. Mater. Sci. Eng. 7, 113–128 (2023).

Wang, L., Gopalan, S. & Naidu, R. Advancements in nanotechnological approaches to VOC detection and separation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 1, 100528 (2023).

Uma, S. & Shobana, M. Metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors in clinical diagnosis and environmental monitoring. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 349, 114044 (2023).

Jana, R., Hajra, S., Rajaitha, P. M., Mistewicz, K. & Kim, H. J. Recent advances in multifunctional materials for gas sensing applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 108543 (2022).

Bălă, G.-P., Râjnoveanu, R.-M., Tudorache, E., Motișan, R. & Oancea, C. Air pollution exposure—The (in) visible risk factor for respiratory diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 19615–19628 (2021).

Piscitelli, P. et al. The role of outdoor and indoor air quality in the spread of SARS-CoV-2: Overview and recommendations by the research group on COVID-19 and particulate matter (RESCOP commission). Environ. Res. 211, 113038 (2022).

Tran, H. M. et al. The impact of air pollution on respiratory diseases in an era of climate change: A review of the current evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 1, 166340 (2023).

Dewangan, S. K., Mohan, M., Kumar, V., Sharma, A. & Ahn, B. A comprehensive review of the prospects for future hydrogen storage in materials-application and outstanding issues. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 16150–16177 (2022).

Goel, N., Kunal, K., Kushwaha, A. & Kumar, M. Metal oxide semiconductors for gas sensing. Eng. Rep. 5, e12604 (2023).

Ou, L.-X., Liu, M.-Y., Zhu, L.-Y., Zhang, D. W. & Lu, H.-L. Recent progress on flexible room-temperature gas sensors based on metal oxide semiconductor. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 206 (2022).

Jappor, H. R. & Khudair, S. A. M. Electronic properties of adsorption of CO, CO2, NH3, NO, NO2 and SO2 on nitrogen doped graphene for gas sensor applications. Sens. Lett. 15, 432–439 (2017).

Jappor, H. R. Electronic and structural properties of gas adsorbed graphene-silicene hybrid as a gas sensor. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 12, 742–747 (2017).

Sanyal, G., Vaidyanathan, A., Rout, C. S. & Chakraborty, B. Recent developments in two-dimensional layered tungsten dichalcogenides based materials for gas sensing applications. Mater. Today Commun. 28, 102717 (2021).

Rohaizad, N., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C., Fojtů, M., Latiff, N. M. & Pumera, M. Two-dimensional materials in biomedical, biosensing and sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 619–657 (2021).

Liang, Q., Zhang, Q., Zhao, X., Liu, M. & Wee, A. T. Defect engineering of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Nano 15, 2165–2181 (2021).

Hayat, A. et al. Recent advances, properties, fabrication and opportunities in two-dimensional materials for their potential sustainable applications. Energy Storage Mater. 59, 102780 (2023).

Sulleiro, M. V., Dominguez-Alfaro, A., Alegret, N., Silvestri, A. & Gómez, I. J. 2D Materials towards sensing technology: From fundamentals to applications. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 38, 100540 (2022).

Jain, S., Trivedi, R., Banshiwal, J. K., Singh, A. & Chakraborty, B. Two-dimensional materials (2DMs): Classification, preparations, functionalization and fabrication of 2DMs-oriented electrochemical sensors. In 2D Materials-Based Electrochemical Sensors (ed. Rout, C. S.) 45–132 (Elsevier, 2023).

Guo, R. et al. Ultrasensitive room temperature NO2 sensors based on liquid-phase exfoliated WSe2 nanosheets. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 300, 127013 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. NO2 gas sensors based on CVD tungsten diselenide monolayer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 529, 147110 (2020).

Kushwaha, A., Kumar, R. & Goel, N. Chemiresistive gas sensors beyond metal oxides: Using ultrathin two-dimensional nanomaterials. FlatChem 1, 100584 (2023).

Saggu, I. S., Singh, S., Singh, S. & Sharma, S. Improved N, N-dimethylformamide vapor sensing using WSe2/MWCNTs composite at room-temperature. Surf. Interfaces 42, 103403 (2023).

Ni, J., Wang, W., Quintana, M., Jia, F. & Song, S. Adsorption of small gas molecules on strained monolayer WSe2 doped with Pd, Ag, Au, and Pt: A computational investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 514, 145911 (2020).

Alenezy, E. K. et al. Low-temperature hydrogen sensor: Enhanced performance enabled through photoactive Pd-decorated TiO2 colloidal crystals. ACS Sens. 5, 3902–3914 (2020).

Dhall, S., Sood, K. & Nathawat, R. Room temperature hydrogen gas sensors of functionalized carbon nanotubes based hybrid nanostructure: Role of Pt sputtered nanoparticles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 8392–8398 (2017).

Mandeep, G. A. et al. DFT study of carbaryl pesticide adsorption on vacancy and nitrogen-doped graphene decorated with platinum clusters. Struct. Chem. 32, 1541–51 (2021).

Xia, S.-Y., Tao, L.-Q., Jiang, T., Sun, H. & Li, J. Rh-doped h-BN monolayer as a high sensitivity SF6 decomposed gases sensor: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 536, 147965 (2021).

Devi, R., Singh, B., Canepa, P. & Sai Gautam, G. Effect of exchange-correlation functionals on the estimation of migration barriers in battery materials. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 160 (2022).

Khan, A. A. et al. Electronic structure, magnetic, and thermoelectric properties of BaMn2As2 compound: A first-principles study. Phys. Scr. 97, 065810 (2022).

Xiao, M. et al. The effects of MS2 (M = Mo or W) substrates on electronic properties under electric fields in germanene-based field-effect transistors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 57, 125101 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Design of Mo2C-MoP heterostructure hydrogen and oxygen evolution bifunctional catalyst based on first principles. Mol. Catal. 552, 113672 (2024).

Chew, K.-H., Kuwahara, R. & Ohno, K. Electronic structure of Li+@ C 60 adsorbed on methyl-ammonium lead iodide perovskite CH3 NH3 PbI3 surfaces. Mater. Adv. 3, 290–299 (2022).

Li, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, D., Xiao, S. & Tang, J. Adsorption behavior of COF2 and CF4 gas on the MoS2 monolayer doped with Ni: A first-principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 443, 274–279 (2018).

Teng, J. et al. Molecular level insights into the dynamic evolution of forward osmosis fouling via thermodynamic modeling and quantum chemistry calculation: Effect of protein/polysaccharide ratios. J. Membr. Sci. 655, 120588 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Dissolved gas analysis in transformer oil using Pt-doped WSe2 monolayer based on first principles method. IEEE Access 7, 72012–72019 (2019).

Cui, H., Zhang, G., Zhang, X. & Tang, J. Rh-doped MoSe2 as a toxic gas scavenger: A first-principles study. Nanoscale Adv. 1, 772–780 (2019).

Kokalj, A. Corrosion inhibitors: Physisorbed or chemisorbed? Corros. Sci. 196, 109939 (2022).

Kumar, J. & Shrivastava, M. Role of chalcogen defect introducing metal-induced gap states and its implications for metal–TMDs’ interface chemistry. ACS Omega 8, 10176–10184 (2023).

Cui, H. et al. DFT study of Cu-modified and Cu-embedded WSe2 monolayers for cohesive adsorption of NO2, SO2, CO2, and H2S. Appl. Surf. Sci. 583, 152522 (2022).

Ren, J. Highly Selective Adsorption on WX2 (X= S, Se, Te) Monolayer and Effect of Strain Engineering: A DFT Study (2021).

Wadhwa, R., Ghosh, A., Kumar, D., Kumar, P. & Kumar, M. Platinum nanoparticle sensitized plasmonic-enhanced broad spectral photodetection in large area vertical-aligned MoS2 flakes. Nanotechnology 33, 255702 (2022).

Pyykkö, P. Additive covalent radii for single-, double-, and triple-bonded molecules and tetrahedrally bonded crystals: A summary. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 2326–2337 (2015).

Alagh, A. et al. Three-dimensional assemblies of edge-enriched WSe2 nanoflowers for selectively detecting ammonia or nitrogen dioxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 54946–54960 (2022).

Zhu, H., Cui, H., He, D., Cui, Z. & Wang, X. Rh-Doped MoTe2 monolayer as a promising candidate for sensing and scavenging SF6 decomposed species: A DFT study. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 1–11 (2020).

Jiang, T. et al. First-principles calculations of adsorption sensitivity of Au-doped MoS2 gas sensor to main characteristic gases in oil. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 13673–13683 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. developed the theory and performed the computations. N.G. verified the analytical methods. A.K. and N.G. contributed to the interpretation of the results and N.G. supervised the project. A.K. wrote the manuscript and N.G. improved the quality of manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kushwaha, A., Goel, N. A DFT study of superior adsorbate–surface bonding at Pt-WSe2 vertically aligned heterostructures upon NO2, SO2, CO2, and H2 interactions. Sci Rep 14, 15708 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65213-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65213-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Adsorption of dibenzothiophene on N-doped TiO₂ system: a DFT and molecular dynamics study

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2026)

-

Effect of strain in beta phosphorus nitride nanosheets on the adsorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a DFT study

Adsorption (2025)

-

Study of SOF2 adsorption properties on α-Al2O3(0 0 0 1) surface based on density functional theory

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)