Abstract

Twelve spiro thiazolidinone compounds (A–L) were synthesized via either conventional thermal or ultrasonication techniques using Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The modification of the traditional procedure by using Fe2O3 nanoparticles led to enhancement of the yield of the desired candidates to 78–93% in approximately half reaction time compared with 58–79% without catalyst. The products were fully characterized using different analytical and spectroscopic techniques. The structure of the two derivatives 4-phenyl-1-thia-4-azaspirodecan-3-one (A) and 4-(p-tolyl)-1-thia-4-azaspirodecan-3-one (B) were also determined using single crystal X-ray diffraction and Hirshfeld surface analysis. The two compounds (A and B) were crystallized in the orthorhombic system with Pbca and P212121 space groups, respectively. In addition, the crystal packing of compounds revealed the formation of supramolecular array with a net of intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions. The energy optimized geometries of some selected derivatives were performed by density functional theory (DFT/B3LYP). The reactivity descriptors were also calculated and correlated with their biological properties. All the reported compounds were screened for antimicrobial inhibitions. The two derivatives, F and J, exhibited the highest levels of bacterial inhibition with an inhibition zone of 10–17 mm. Also, the two derivatives, F and J, displayed the most potent fungal inhibition with an inhibition zone of 15–23 mm. Molecular docking investigations of some selected derivatives were performed using a B-DNA (PDB: 1BNA) as a macromolecular target. Structure and activity relationship of the reported compounds were correlated with the data of antimicrobial activities and the computed reactivity parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

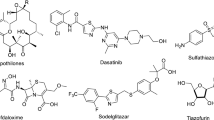

Organic spiro compounds are made up from at least two rings connected by a single atom identified as a spiro-atom. Numerous derivatives that are extracted from diverse natural sources contain these types of molecules1,2,3. This category of compounds exhibits broad spectrum properties of different biological functions4. In addition, owing to the structure–activity relationship of these spiro compounds, many applications are found their way in the medicinal and pharmacological fields for the identification of novel medications5,6,7. It is worth to mention that the special class of spiro heterocyclic compounds containing sulfur and nitrogen atoms are widely employed as essential components in the production of many drugs8,9,10,11. For instance, the spiro-thiazolidinone nucleus yields a range of derivatives with diverse biological functions12,13,14, Fig. 1. The antibacterial, antifungal and antithyroid efficacy of these compounds were linked to their N–C–S linkage13,15. Further, many additional biological functions for the thiazolidinone derivatives such as antitubercular16, antioxidant17, analgesic18, anticonvulsant19, anti-inflammatory20, antihyperglycemic21, diuretic22, antihistaminic23, antidiabetic24,25, cyclooxygenase inhibitors26, and lipoxygenase inhibitors26 were also explored27,28, Fig. 2.

Recently, a green technique using ultrasound and microwave irradiations has employed to efficiently synthesize many heterocycle derivatives that are additive-free, high yields, short reaction period and environmentally safe29,30,31,32. Notably, the multicomponent reactions (MCRs) are also highly effective routs in the synthetic chemistry33,34,35,36,37. In addition, the fields of organic synthesis and drug development extremely require reducing the number of synthetic steps to create the desired molecules from the readily available starting reagents38,39,40.

Nowadays, nanoparticles (NPs) are frequently employed in many chemical reactions, such as synthesis of heterocyclic compounds, as heterogeneous catalysts. This is because of their high surface-to-volume ratio, which aids in the catalytic process41. Magnetite (Fe3O4) has been identified as the ideal and most widely used heterogeneous catalyst because of its low cost, ease of preparation, handling and recovery with an external magnetic field as well as the high catalytic activities and reactivity in various organic transformations42,43,44,45,46. However, other types of NPs iron oxide, like hematite (α-Fe2O3), spinel ferrites (MFe2O4), and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), are also used because of their ferrimagnetism and environmental stability. Fe2O3 nanoparticles are generally considered safe and biocompatible, making them suitable for use in organic synthesis, especially in the context of pharmaceutical and fine chemical production. The use of Fe2O3 nanoparticles aligns with the principles of green chemistry, as they can be used to develop environmentally friendly and sustainable synthetic protocols47.

The syntheses of novel thiazole derivatives using either conventional or sonication methods were investigated due to their different potential biological activities. Notably, the use of ultrasonic technique has commonly used in the synthesis of those derivatives48,49. Herein, we report the nano catalytic synthesis of novel thiazolidinones by both conventional and sonication methods (Scheme 1). The reported derivatives were characterized by the several spectroscopic and analytical tools along with theoretical DFT and molecular docking calculations. The structures of the precursors A and B were also solved using single crystal X-ray diffraction and Hirshfeld surface studies. Antimicrobial activities of the synthesized compounds also demonstrated strong inhibition efficacy towards the screened microorganisms. Structure–activity relationship (SAR) of the reported thiazolidinone derivatives were correlated with their biological activities along with the theoretical findings as well.

Discussion

Synthesis and characterization

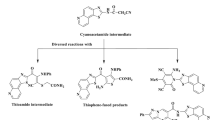

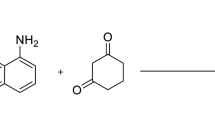

One-pot multicomponent synthesis (MCS) is a powerful synthetic strategy that involves the simultaneous reaction of multiple reactants to yield a product in a single reaction vessel48. Fe2O3 nanoparticles, on the other hand, have significant importance in organic syntheses, especially those of one-pot MCS, due to their unique properties and catalytic capabilities. The unique properties and catalytic performance of the Fe2O3 NPs make them valuable catalysts for the development of sustainable and efficient synthetic routes. Therefore, this work intended to synthesize a new series of spiro thiazolidine-4-one derivatives, which were prepared via the reaction of cyclohexanone, thioglycolic acid, and different aromatic amines using a one-pot multicomponent technique. Thermal conventional and sonication methods in the presence or absence of Fe2O3 NPs catalyst were employed to compare the % yield and reaction, Table 1. In the absence of the nanocatalyst, the reactions took about 8 h to give the desired products with a yield ranging from 58 to 75%. Furthermore, in the presence of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst, the reaction occurred in ~ 4 h with higher yields up to 93%. On the other hand, when the reactions were carried out at 60 °C by using sonication method and in the absence of Fe2O3 NPs, the products were gotten in about 2 h. In presence of the nano catalyst, the reactions took only one hour with yields of more than 90%, Table 1. Therefore, it was concluded that Fe2O3 nano catalyst facilitated the reactions and cause to obtain higher product yields in a shorter time. In addition, the heterogeneous nature of the catalyst allowed easy separation and recovery that simplified the purification process. Fe2O3 NPs were either magnetically separated or filtered, which enabled their reuse as well as reduced production of waste. This is because of their high surface-to-volume ratio, Fe2O3 NPS absorbs the reactant on its surface which facilitates the reaction to take place as shown in the plausible mechanism50,51 (Scheme 2). The chemical and structural formulae of the reported compounds were characterized by different analytical and spectroscopic tools such as IR, NMR, and Mass spectrometry. The IR spectra of the thiazolidinone derivatives (A–L) showed the appearance of stretching frequency bands for the C=O group at the range of 1665–1693 cm−1. On the other hand, the 1H-NMR spectra for the compounds exhibited singlet signals at 3.62–3.93 ppm range due to the CH2 of thiazolidinone along with multiplet signals at 1.04–2.22 ppm attributed to the aliphatic protons of the cyclohexane. Further, the aromatic protons of the different derivatives occurred in the 1H-NMR spectra in the aromatic region at 6.29–8.03 ppm. In addition, the aliphatic protons (C–CH3) of compounds C, H and I appeared as singlet signals ranging from 2.12 to 2.27 ppm. On the other side, the protons of the N–CH3 of the compound I were shown as a singlet at 3.14 ppm. This low field shift was due to deshielding effect of the attached electronegative nitrogen atom. The mass spectra for all the derivatives illustrated molecular ion (M+) peaks corresponding to the parent compounds.

X-ray crystallographic studies of A and B

Colorless block crystals suitable for X-ray analysis of the two compounds A and B were obtained via slow evaporation of alcoholic solutions. The structural studies indicated that the two compounds A and B crystallized in the orthorhombic system as Pbca and P212121 space groups, respectively. Crystal data and structure refinement parameters are presented in Table 2 and the asymmetric part of the two structures was found to contain one molecule (Fig. 3). Table 3 tabulates the bond length and bond angle values for the two compounds A and B along with the corresponding values obtained from the DFT calculations. As can be seen from Table 3, the bond angles and bond lengths are in the normal ranges shown for similar organic compounds52,53.

The valence geometry of the reported structures is similar and typical for these types of compounds. However, the structures of the two compounds have slightly different conformations, as shown in Fig. 4 (structures have been superimposed with 5-membered rings). The external 6-membered rings in these structures are different twisted relative to the plane of the 5-membered ring. In A, the dihedral angles between the plane of the 5-membered ring, and aromatic ring and cyclic ring are 80.26° and 81.49°, respectively. Whereas, in B, the values of the analogous dihedral angles are equal to 87.32 and 79.92°.

The crystal packing of the compounds revealed that the molecules are forming supramolecular array with a net of intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions (Figs. 5 and 6). Analysis of the crystal packing of A and B showed the presence of intermolecular C–H⋯S and C–H⋯O interactions (Table 4). In A, C–H⋯π interactions were also detected, where there were C16–H16A⋯πC12–C17 [3/2−x, 1/2 + y, z] interactions with distance of 2.829(12) Å (Fig. 5II).

Symmetry codes: (i) –x + 1, − y + 1, − z + 1; (ii) –x + 1/2, y − 1/2, z; (iii) − x + 1/2, y + 1/2, z; (iv) x + 1, y, z; (v) x − 1/2, − y + 3/2, − z + 1.

Analysis of Hirshfeld surfaces

Hirshfeld surface analysis of the unit cell packing of a crystal gives useful information evidencing the presence of intermolecular interactions of individual atoms within the crystal surface and gives plots for a three-dimensional Hirshfeld surface and a two-dimensional fingerprint. The study uses the electron distribution within molecule owing to geometry and nature and directions of other species that form close contacts54. Hirshfeld surface representations of compounds A and B were shown as a normalized contact distance (dnorm), shape index and curvedness graphs created by using the free downloaded Crystal Explorer 21.5 software55 and the crystallographic information file (CIF) of the two compounds (Fig. 7). The electrostatic potential surface in the dnorm plot is presented as red, blue, and white color schemes. The dnorm value depends on three parameters: de, di and vdw, where de = range between point to nearest nucleus external to the surface; di = space from nearest internal nucleus to surface; and vdw = van der Waals radii. The red spots are characteristic for the short interactions that occur in the molecule and have negative dnorm values, while blue zones are due to longer contacts with positive dnorm values. On the other hand, white zones mean that the distance between contacts equal to van der Waal intervals, i.e., dnorm = zero. The dnorm mapping analysis exhibited the relative locations of adjoining atoms belonging to molecules that interact with each other. The shape index and curvedness mapped on Hirshfeld surface analyses provide information about the other weak interactions present in the two compounds. In the shape index plot, the C–H⋯π and C=O⋯π interactions are indicated as red regions around contributing atoms. The π–π interactions in the molecule are indicated by flat regions on the curvedness surface (Fig. 7). The quantitative measurements of the Hirshfeld surface for compound A were: total volume, 308.16 Å3; area, 270.79 Å2; globularity, 0.815 and asphericity (0.060), while for compound B were: total volume, 329.52 Å3; area, 288.17 Å2; globularity, 0.801 and asphericity (0.110). The values of globularity for the two compounds were less than 1.0, which indicated that the molecular surface is more structured. The dnorm surface of A was charted over the range of − 0.2377 to 1.2399 a.u with a mean of 0.4923 a.u, while the dnorm surface of B occurred over the range of − 0.2118 to 1.3406 a.u with a mean of 0.5003 a.u. The dnorm graph of A and B displayed bright red spots around oxygen atoms and concluded strong intermolecular interactions (Fig. 7).

Quantitative analysis of the percentage participation of every interatomic contact in the crystal unit can be executed by plotting the two-dimensional (2D) fingerprint representations. Selected 2D fingerprint plots for X-ray crystals of A and B are given in the ranges of 0.6–2.4 Ǻ for contacts with the de and di coordinate scales displayed on the plot axes (Fig. 8). Hirshfeld surface mapped with the shape-index property demonstrating the inter-atomic contacts interactions H⋯H, H⋯C and H⋯O in the X-ray crystal of the two compounds A and B are illustrated in Fig. 8. The most significant contributions were from the H⋯H interatomic contacts, where displayed the highest contribution in the crystal units of A and B with 63.9% and 68.7%, respectively, which may be due to the predominance of hydrogen atoms in the crystals. The sparkle green zone on the fingerprint graph of the H⋯H interatomic interactions might be due to stacks formation through π⋯π interactions. On the other side, the Hirshfeld surfaces exhibited small percentage contributions from the H⋯C, H⋯O and H⋯S interatomic contacts (Fig. 9).

The pairwise interaction energies for compound B within a crystal were calculated using Crystal Explorer 21.5 software. The total interaction energy (− 131.6 kj/mol) is composed of four ingredients: electrostatic (− 46.2 kj/mol), polarization (− 20.6 kj/mol), dispersion (− 150.90 kj/mol), and repulsion energy (80.20 kj/mol). The individual ingredients of energy and total energy for the specific molecular pairs are tabulated in Table 5. The dispersion energy was predominant. The energy frameworks that visualize strength of interaction energy are illustrated in Fig. 10 for Coulombic (red), dispersion (green), and total energy (blue). The radii of cylinders connecting the centroid of the molecules represent the relative interaction energy strengths56.

Stereochemistry and global reactivity descriptors computations

The energetically optimized structure geometries, energies and global reactivity parameters for some selected compounds (A, B, D, E, F, G, I, and J) were computed using the hybrid density function theory implemented in Gaussian 09w software57. These derivatives were selected because of their higher antimicrobial activities (vide infra). The highest occupied and lowest unoccupied (HOMO and LUMO) molecular orbitals are commonly used to extract valuable information about the optical and electric properties of compounds. In addition, these frontier molecular orbitals are used to characterize the different models of charge transfer (CT) within the molecule58,59. The lowest energies of minimized stable orientations of the compounds were estimated by focusing on the arrangement of the important function groups in the molecules and their influence on each other. Figures 11 and 12 display the geometrically optimized structures of the compounds. The orientation of the basic unit (thia-4-azaspirodecan-3-one) in the investigated compounds, which was consisted of the two parts thiazolidin-4-one and cyclohexane, was almost the same. The cyclohexane moiety opted for the stable chair form and nearly perpendicular to the thiazolidin-4-one five-membered ring. The unique structural features of each compound were inherited from the specific substituent for each compound. The energy minimized structures of the two compounds A and B (Fig. 11) were almost identical to those obtained from the X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the bond distances and bond angles obtained from the DFT calculations are very close to those extracted from the X-ray analysis (Table 3). In case of the compounds D and E. either the nitro or F group and phenyl moieties of the nitrobenzene and fluorobenzene substituents were in one plane. The dihedral angles for C12–C13–N18–O19 (D) = 179.3° and for C13–C14–C15–F18 (E) = 179.7°. In addition, the plane of the nitrobenzene or fluorobenzene substituent was nearly perpendicular to that of the thiazolidin-4-one five-membered ring and acquired a dihedral angle = 84.7° (C3–N7–C17–C12) and 85.6° (C3–N7–C16–C17), respectively, like those observed for the two compounds A and B.

The other four compounds (F, G, I and J, Fig. 12) also exhibited similar trends. In case of compound I, the substituent phenyl-dimethyl-pyrazolone was not planar. The plane of the phenyl ring exerted dihedral angles with the plane containing the dimethyl-pyrazolone moiety equal to 25.4° (N2–N3–C24–C23) and 47.8° (C4–N3–C24–C25). In contrast, the phenyl-pyrazolone substituent in compound J was planar (the dihedral angle of N2–N3–C20–C21 = 173.9°). This contradiction could arise from the presence of the two methyl groups in compound I. All the other bond lengths and bond angles of the investigated compound were in normal values as those observed before50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61.

The global chemical reactivities of the investigated compounds (A, B, D, E, F, G, I, and J) have been calculated49 such as frontier HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals, energy gap (ΔE), chemical potential (V), ionization potential (I), electronegativity (Χ), electron affinity (A), chemical softness (S) and chemical hardness (η), electrophilicity index (ω) along with the total energy and dipole moment (DM) values were calculated using the hybrid DFT method (Table 6). The energies of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals define the donation and withdrawal ability of the electrons within the molecule. The difference between the energies of these two orbitals (ΔE) points to the molecular stability and electrical transport properties. Obviously, the small values of ΔE declare the facile charge transfer (CT) and polarization in the electrostatic potentials that show partial transfer of the electron from the highest occupied to the lowest unoccupied levels. Compound D illustrated the lowest ΔE (3.48 eV), while compound B had the highest value (5.73 eV). This was also consistent with the opposite values for the electronegativity and electrophilicity index of the two compounds (Χ = 4.82 and 3.34 eV, and ω = 6.68 and 1.95 eV for D and B, respectively). Furthermore, the small values of the chemical hardness and chemical softness for the derivatives pointed out to the ability of charge transfer within these molecules (Table 6). Again, compound D had the highest value, while compound B had the lowest one.

The antimicrobial activities

Two Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis), two Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and two fungi (Candida albicans and Aspergillus flavus) were checked for the antimicrobial activities of the reported (A–L) compounds. Ampicillin and Clotrimazole were performed as standards for the antibacterial and antifungal measurements, respectively. The findings of antimicrobial activities of the screened compounds showed that they have diverse activities towards the screened strains with respect to the selected standards (Figs. 13 and 14). The tested derivatives exhibited, with different ranges, capabilities to inhibit the metabolic development of the screened microorganism and pointed out that they have wide-spectrum properties. Obviously, the different structures and substituents of the reported compounds functioned as important roles and considered the key pillar for the biological activities (vide infra). The activity of these products might be attributed to the presence of C=O and C=N, F, Cl and NO2 functional moieties. The formation of hydrogen-bonding interactions between those groups and the active zones of cell constituents along with interference with normal cell were thought to be the principal mode of action of the inhibitors62,63. The cell membrane of bacteria consists of permeable lipid layers that allow the passage of soluble lipid reagents. Thus, the lipophilicity properties play a vital role that affects the inhibition of bacteria. Therefore, increasing the lipophilicity might increase the inhibition ability of investigated compound. Figure 12 displays that most of the tested derivatives have higher inhibition function towards the Gram-positive bacteria than the Gram-negative ones. In addition, the two derivatives F and J exhibited the highest bacterial inhibition. It is worth to mention that compounds K and L showed no inhibition activities against the two types of bacteria. On the other hand, the investigated compounds showed moderate inhibition towards the screened fungi (Fig. 14). Again, the two derivatives F and J displayed the most fungal inhibition.

Structure–activity relationship (SAR)

The results of this study confirmed the presence of relations between the antimicrobial effects of the investigated compounds and the different types of the substituents attached to the thia-4-azaspirodecan-3-one precursor. It is clearly noted that the involved various substituents and the structure variety of the examined derivatives played a distinguished role in their biological activities. To understand the structure–activity relationship between the different compounds, we considered the findings obtained from the reactivity descriptors (Table 6) along with the antibacterial activity data (Table 7 and Figs. 13 and 14). It is well known that the structure framework of a compound would reflect its activity, which means that similar compounds could have comparable activities. This condition is treated as the central backbone proposition of structure–activity relationship (SAR). The SAR concept based on the assumption that structural characteristics of a chemical molecule, like the geometry and electronic property, has countenances responsible for the chemical, physical, and biological properties64. Therefore, this concept is commonly used in the drug design and drug discovery studies to lead the development and improvement of desired new drugs. From the correlation between the antimicrobial activities and the structures of compounds A–L (Table 7), it can be noticed the effect of different substituents on the biological behavior. For instance, compound A showed moderate microbial inhibitions towards the tested microorganism. However, inhibition of the Gram-positive bacteria was more effective than the Gram-negative bacteria. On substituting the phenyl group of compound A by a tolyl group to have compound B, the antimicrobial activities were significantly reduced; it showed no activity towards the Gram-negative bacteria. Compound C with the o-xylene substituent also showed depressed antimicrobial activity although it was better than B. The lesser antimicrobial activities of B and C could be returned to the presence of branched methyl groups. On the other hand, the three substituents nitrobenzene, fluorobenzene and chlorobenzene related to the compounds D, E and F showed much better enhancement in antimicrobial activities than even compound A (Table 7). The three compounds D, E and F had comparable inhibition power (Table 7 and Figs. 13 and 14). The antibacterial abilities of these compounds against the Gram-positive bacteria were higher than the inhibition of Gram-negative bacteria. Interestingly, the two compounds E and F showed identical chemical reactivity descriptors (Table 6). Further, compound D illustrated the highest dipole moment and electrophilicity index value, and the lowest energy gap, chemical hardness, and chemical softness values probably due to the presence of NO2 group. From the other side, the compound G with p-dichlorobenzene substituent exhibited diminished antimicrobial activity due to the low dipole moment (Table 6) caused from the presence of the two chloro atoms in position para to each other. Compound H with the dimethylpyrimidine moiety also showed weaker antimicrobial activity towards the tested bacteria and fungi. However, its inhibition power was better than compound G, Figs. 13 and 14. On comparing the inhbition cabability of the two derivatives I and J with the mioeties dimethyl-phenyl-pyrazolone and phenyl-pyrazolone, respectively, the data showed that the compound J displayed better inhibition. In fact, compound J had the best antimicrobial activity towards the screened microorganism (Table 7). It also had the highest electrophilicity index and the lowest energy gap, chemical hardness, and chemical softness after the compound D (Table 6). In all derivatives, it is noted that the presence of the methyl groups caused depression of the antimicrobial activities. The two compounds K and L having the thiazole and benzothiazole substituents, respectively, exhibited non-antimicrobial activity; the presence of those two substituents caused quenching of their inhibition. From the antibacterial findings, it can be noted that the activity inhibition of the reported derivative was much better with the Gram-positive bacteria than versus the Gram-negative bacteria. Mechanisms of interactions between inhibitors like synthetic compounds with bacteria could be through either inhibition of cell wall synthesis, diffusion or cell permeability. The wall thickness of the bacteria cell can thus play a critical function against the screened inhibitor. The cell wall of the Gram-positive bacteria is mainly thicker (20–30 nm) with rigid membrane structure than the thickness of cell wall of the Gram-negative bacteria (8–12 nm)65. Therefore, according to the results of the antibacterial properties, it can be concluded that the mechanism of action of the reported derivative with the screened bacteria was presumably inhibition of the cell wall synthesis.

Molecular docking investigations

Molecular docking analysis is an eminent method to evaluate the molecular interactions between tiny, synthesized molecules with selected macromolecular biological receptor66. The findings of the molecular docking data are commonly concerned by deducing the conformation poses that contributed with the binding zones of the macromolecular targets in order to host a hydrophobic inhibitor. These findings would also estimate the way to how a docked inhibitor is fundamentally settled down inside the minor grooves of the receptor. In the current investigation, molecular docking estimations of some selected compounds (A, B, D, E, F, G, I and J) were executed by using a B-DNA (PDB ID:1BNA) to declare the interaction types and to distinguish between the plausible binding poses and energy values. The binding score, hydrophobic interaction, and the different types of hydrogen bonding were the main parameters that used to detect the best molecular conformation between receptor and inhibitor. Figures 15 and 16 illustrate the two- and three-dimension representations of the interacted compounds with a nucleic acid. The molecular docking results (score functions, rmsd values, types and energies of interactions) are given in Table 8. As can be noted from the figures, the hydrophobic ligand exposure was the most interaction type of the compounds with the tested target. Obviously, the polar parts of the compounds that contained O, N, S, Cl and F atoms had the highest hydrophobic retardation67,68. Many residues from the four nucleotide bases consisting of the DNA, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T), were involved in the interactions, such as DA 17B, DA 18B, DA 5A, DA6A, DC 11A, DC 9A, DC 15B, DG 16B, DG 12A, DG 10A and DT 19B. The compound D showed also a greasy hydrogen-bond sidechain acceptor through the residual DG 10A with the oxygen of the nitro group, while the compound E exhibited a greasy hydrogen-bond sidechain donor and hydrogen-bond sidechain acceptor via the residue DA 17B with the sulfur of the thiazolidinone moiety (Fig. 15). Interestingly, the sulfur atom of the thiazolidinone part of compound G underwent three types of hydrogen bonds with two residues of the adenine base (two greasy hydrogen-bonds sidechain donors with DA 17B and a hydrogen-bond backbone acceptor with DA 18B), Table 8. The compound I, on the other hand, showed two types of H-bond interactions. It displayed two greasy hydrogen-bond sidechain acceptors with the guanine residues DG 4A and DG 22B. In addition, the compound exhibited a π-H type of interaction between the DC 23B residue and the five-membered ring of the dimethyl-pyrazolone moiety (Table 8). The investigated compounds showed large negative values for the score function S (Table 8). These high negative values implied that the docked compounds had a high binding affinity towards the screened receptor. The binding affinities of the reported compounds towards the DNA receptor were found to possess the order: J > A > B > D > F > I > G > E.

Experimental

Reagents and instruments

Chemicals, reagents, solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, and they were used as received. The two compounds A and B were synthesized according to a previous reported procedures69. Melting points of the different derivatives were measured using Gallen Kamp melting point equipment (Sanyo Gallen Kamp, UK). Digital Ultrasonic Cleaner CD-4830 (35 kHz, 310 W) was used to carry out the ultrasound-aided reactions. The IR spectra (KBr pellets, cm−1) were captured using a Pye-Unicam SP-3-300 FT-IR spectrophotometer. Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer was used for the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra in DMSO-d6. Mass spectra were performed on a Shimadzu GCMS-QP-1000EX mass spectrometer. Microanalytical analyses (CHN) were executed on a Perkin-Elmer analyzer (CHN-2400). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) sheets covered with Merck 60 F254 plates’ UV fluorescent silica gel were used to monitor the reactions, and they were visualized using a UV lamp and various solvents as mobile phases. All reagents and solvents were purified and dried by standard techniques.

Synthesis

Method a

A mixture of cyclohexanone (0.01 mol), thioglycolic acid (0.01 mol), and some selected aromatic amines (0.01 mol) in 20 mL dry toluene was heated to reflux for 8 h. The reaction mixture was cooled, and the formed precipitate was filtered off, dried, and then recrystallized from DMF to give the desired compound (A–L).

Method b

A mixture of cyclohexanone (0.01 mol), thioglycolic acid (0.01 mol), the selected aromatic amines (0.01 mol) and a catalytic amount of iron oxide nanoparticles in 20 mL dry toluene was placed in Erlenmyer flask (50 mL). The reaction mixture was then subjected to ultrasound waves at room temperature for 60 min. The formed precipitate was filtered, dried, and recrystallized from DMF to afford the desired compound (A–L).

4-(3,4-dimethylphenyl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (C)

White crystals; m.p.185–186 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3014 (CH aromatic), 2920 (CH aliphatic), 1668 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.49–1.82 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 2.20 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.22 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.74 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 6.86 (d, 1H, Ar–H), 7.04 (d, 1H, Ar–H), 7.23 (s, 1H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 171.3 (C=O), 139.2 (Ar–C–NThiazolone), 136.6 (Ar–C), 133.9 (Ar–C), 131.3 (Ar–C), 129.3 (Ar–C), 125.7 (Ar–C), 66.3 (Spiro-C), 35.29 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.0 (CH2 Thiazolone), 26.9 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 24.5 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 18.1 (CH3), 17.3 (CH3); MS (m/z) (%): 275 (M+, 17), 130 (100); Anal. Calcd for: C16H21NOS (275.41): C, 69.78; H, 7.69; N, 5.09; Found: C, 69.67; H, 7.55; N, 4.96%.

4-(3-nitrophenyl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (D)

Off white crystals; m.p.111–113 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3010 (CH aromatic), 1684 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.26–1.95 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.89 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.49–7.83 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 8.03 (s, 1H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 172.1 (C=O), 149.9 (Ar–C-NO2), 141.8 (Ar–C–NThiazolone), 133.9 (Ar–C), 130.4 (Ar–C), 124.7 (Ar–C), 119.8 (Ar–C), 66.8 (Spiro-C), 34.4 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.2 ( CH2 Thiazolone), 26.9 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 23.1 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane); Anal. Calcd for: C14H16N2O3S (292.35): C, 57.52; H, 5.52; N, 9.58; Found: C, 57.45; H, 5.39; N, 9.51%.

4-(2-fluorophenyl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (E)

White crystals; m.p.125–127 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3073 (CH aromatic), 1667 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.35–1.90 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.79 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.12–7.91 (m, 4H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4 (C=O), 162.2 (Ar–C–F), 131.3 (Ar–C–NThiazolone), 128.9 (Ar–C), 125.7 (Ar–C), 123.5 (Ar–C), 119.8 (Ar–C), 66.3 (Spiro-C), 37.6 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.9 (CH2 Thiazolone), 26.3 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 24.5 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane); MS (m/z) (%): 265 (M+, 36), 91 (100); Anal. Calcd for: C14H16FNOS (265.35): C, 63.37; H, 6.08; N, 5.28; Found: C, 63.21; H, 5.92; N, 5.09%.

4-(2-chlorophenyl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (F)

White crystals; m.p.105–107 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3062 (CH aromatic), 1670 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.33–2.08 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.79 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.13–7.92 (m, 4H, Ar–H); Anal. Calcd for: C14H16ClNOS (281.06): C, 59.67; H, 5.72; N, 4.97; Found: C, 59.49; H, 5.55; N, 4.78%.

4-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (G)

White crystals; m.p.105–107°C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3061 (CH aromatic), 1680 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.46–2.26 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.83 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.22 (d, 1H, Ar–H), 7.49 (d, 1H, Ar–H), 7.93 (s, 1H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 170.9 (C=O), 142.4 (Ar–C), 138.7 (Ar–C), 133.1 (Ar–C), 129.9 (Ar–C), 124.8 (Ar–C), 119.9 (Ar–C), 65.38 (Spiro-C), 35.3 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.6 (CH2 Thiazolone), 26.0 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 23.4 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane); Anal. Calcd for: C14H15Cl2NOS (316.24): C, 53.17; H, 4.78; N, 4.43; Found: C, 53.04; H, 4.68; N, 4.36%.

4-(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (H)

White crystals; m.p.182–183°C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3012 (CH aromatic), 1921 (CH aliphatic), 1693 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.22–1.87 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 2.12 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 3.62 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 6.29 (s, 1H, Ar–H); MS (m/z) (%): 277 (M+, 38), 111 (100); Anal. Calcd for: C14H19N3OS (277.39): C, 60.62; H, 6.90; N, 15.15; Found: C, 60.55; H, 6.82; N, 15.07%.

4-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (I)

White crystals; m.p.166–167 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3022 (CH aromatic), 1916 (CH aliphatic),1713 (C=O), 1665 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.14–2.17 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 2.27 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.14 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.64 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.11–7.49 (m, 5H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 168.1 (C=O), 161.9 (C=O), 134.2 (C Pyrazolone), 133.9 (Ar–C), 130.7 (2) (Ar–C), 126.3 (2) (Ar–C), 103.6 (C Pyrazolone), 64.7 (Spiro-C), 37.6 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 33.4 (N–CH3), 30.1 (CH2 Thiazolone), 26.7 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 22.8 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 14.6 (CH3); Anal. Calcd for: C19H23N3O2S (357.14): C, 63.84; H, 6.49; N, 11.76; Found: C, 63.77; H, 6.41; N, 11.68%.

4-(5-oxo-1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (J)

White crystals; m.p.156–158°C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3082 (CH aromatic), 1673 (C=O), 1706 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.01–2.22 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.15 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.65 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.32–7.49 (m, 5H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.5 (C=O), 173.0 (C=O), 156.4 (N–C=N Pyrazolone), 139.7 (Ar–C–N), 130.1 (2) (Ar–C), 127.8 (Ar–C), 124.0 (2) (Ar–C), 65.7 (CH2 Pyrazolone), 64.3 (Spiro-C), 35.6 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.0 ( CH2 Thiazolone), 25.7 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 23.4 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane); Anal. Calcd for: C17H19N3O2S (329.42): C, 61.98; H, 5.81; N, 12.76; Found: C, 61.88; H, 5.73; N, 12.69%.

4-(thiazol-2-yl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (K)

White crystals; m.p.172–173 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3084 (CH aromatic), 1684 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.45–1.82 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.88 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.40 (d, 2H, Ar–H), 7.59 (d, 2H, Ar–H); MS (m/z) (%): 254 (M+, 11), 150 (100); Anal. Calcd for: C11H14N2OS2 (254.37): C, 51.94; H, 5.55; N, 11.01; Found: C, 51.82; H, 5.42; N, 10.91%.

4-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-3-one (L)

White crystals; m.p.143–144°C; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3015 (CH aromatic), 1673 (C=O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.52–1.89 (m, 10H, Cyclohexane), 3.93 (s, 2H, CH2 Thiazolone), 7.34 (dd, 1H, Ar–H), 7.44 (dd, 1H, Ar–H), 7.83 (d, 2H, Ar–H), 7.99 (d, 2H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4 (C=O), 163.4 (N–C=N Pyrazolone), 149.7 (Ar–C), 130.1 (Ar–C), 127.2 (Ar–C), 124.4 (Ar–C), 121.4 (Ar–C), 119.9 (Ar–C), 67.8 (Spiro-C), 35.0 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane), 31.1 (CH2 Thiazolone), 26.7 (CH2 Cyclohexane), 24.8 (2 CH2 Cyclohexane); Anal. Calcd for: C15H16N2OS2 (304.43): C, 59.18; H, 5.30; N, 9.20; Found: C, 59.03; H, 5.24; N, 9.13%.

X-ray structure analysis of A and B

The X-ray data for colorless block crystals of A and B with size of 0.17 × 0.03 × 0.03 and 0.20 × 0.14 × 0.02 mm were collected at 100(2) K with Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S (Rigaku-Oxford Diffraction) four circle diffractometer with a mirror monochromator and a microfocus CuKα radiation source (λ = 1.54184 Å). The obtained data set was processed with CrysAlisPro software70. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined with full-matrix least-squares method on F2 with the use of SHELX2018 program packages5. Details of the data processing and refinements were given before71,72. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, while hydrogen atoms were refined isotropically, and were positioned geometrically and constrained to ride on their parent atoms with CH = 0.95–0.99 Å. A summary of the crystal data and refinement details are given in Table 2. The structural data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC No. 2295434 and 2,295,435 for A and B, respectively).

Hirshfeld surface study

Hirshfeld surface analyses were performed to assess the inter- and intra-molecular interactions of the molecular crystal of A and B using the Crystal Explorer 21.5 software73. Calculations were done by using the crystallographic information (cif) files of both A and B compounds.

Stereochemistry and reactivity descriptors calculations

The energetically optimized structures, energies and the global reactivity parameters for some selected compounds were performed using Gaussian 09w software55. The DFT (B3LYP) method with the basis set 6-31G (d,p) and double zeta plus polarization for hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur and chloride was adopted.

Antimicrobial analysis

The antimicrobial activities of the synthesized compounds were screened against two Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis), two Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and two fungi (Candida albicans and Aspergillus flavus). Details of the experimental procedures were previously reported59,74. Ampicillin was used as an antibiotic standard and Clotrimazole was performed as standard for the antifungal estimations. The percentage activity index for the compounds was calculated using the formula:

Molecular docking studies

The molecular docking studies were performed by Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software package version 2014.0901. The X-ray crystal structure of a B-DNA with the PDB code 1BNA was downloaded from Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) database55.

Conclusion

Conventional thermal or green ultrasonication synthesis of some molecularly designed spiro thiazolidinone compounds were performed. The structure features of the derivatives were explored from their spectroscopic characteristics. The X-ray diffraction and Hirshfeld surface studies of the single crystals of two compounds indicated the formation of supramolecular array with a net of intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions. The energetical optimized geometries of some selected derivatives as well as the calculated reactivity descriptors distinguished their interesting structural arrangements and reactivity. The antimicrobial screening of the compounds versus strains from G+ bacteria, G– bacteria and fungi revealed their potency as potential biologically active reagents. In addition, molecular docking studies of some thiazolidinones interpreted their high binding affinity towards a B-DNA macromolecular receptors (Supplementary information). Structure–activity relationships of the reported thiazolidinone derivatives were also correlated with the antimicrobial results.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Supporting information files containing complete crystallographic data (CIF files) for the two compounds A and B have been submitted to the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with reference CCDC deposition no. 2295434 and 2,295,435, respectively.

References

Sathish, M., Sakla, A. P., Nachtigall, F. M., Santos, L. S. & Shankaraiah, N. TCCA-mediated oxidative rearrangement of tetrahydro-β-carbolines: facile access to spirooxindoles and the total synthesis of (±)-coerulescine and (±)-horsfiline. RSC Adv. 11, 16537–16546 (2021).

Xi, Y. K. et al. Total synthesis of spirotryprostatins through organomediated intramolecular umpolung cyclization. Chem. A Eur. J. 25, 3005–3009 (2019).

Song, H. et al. A concise synthesis of (-)-dihydrospirotryprostatin B via tandem Michael addition. Tetrahedron Lett. 85, 153486 (2021).

Zheng, Y., Tice, C. M. & Singh, S. B. The use of spirocyclic scaffolds in drug discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3673–3682 (2014).

Hui, Y. et al. Facile synthesis of spiro thiazolidinone via cyclic ketones, amines and thioglycolic acid by MCM-41-Schiff base-CuSO4·5H2O. Res. Chem. Intermed. 47, 521–532 (2021).

Al-Romaizan, A. N. Synthesis, Characteristic and Antimicrobial Activity of Some New Spiro [indol-thiazolidon-2, 4-diones] and Bis (5-fluorospiro [indoline-3, 2’-thiazolidine]-2, 4’-dione) Probes. Int. J. Org. Chem. 10, 77–87 (2020).

Salama, M., El-Shahat, M., Elhefny, E. & El-Sayed, A. A novel fused pyridopyrimidine derivatives: Synthesis and characterization. Int. J. Pharm 5, 53–58 (2015).

Bodryakov, A., Aliev, A. Y. & Rustamova, S. Biological activity of new sulfur-containing derivatives of nitrogen heterocycles, containing carbodithiotate group and quaternized nitrogen atom. Hayчнo-пpaктичecкий жypнaл 4, 25 (2020).

Sharma, P. K., Amin, A. & Kumar, M. A review: Medicinally important nitrogen sulphur containing heterocycles. Open Med. Chem. J. 14, 49–64 (2020).

Flefel, E. M., El-Sofany, W. I., El-Shahat, M., Naqvi, A. & Assirey, E. Synthesis, molecular docking and in vitro screening of some newly synthesized triazolopyridine, pyridotriazine and pyridine–pyrazole hybrid derivatives. Molecules 23, 2548 (2018).

El-Shahat, M., Salama, M., El-Farargy, A. F., Ali, M. M. & Ahmed, D. M. Effective pharmacophore for CDC25 phosphatases enzyme inhibitors: Newly synthesized bromothiazolopyrimidine derivatives. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 21, 118–131 (2021).

Singh, R., Ahmad Ganaie, S., Singh, A. & Chaudhary, A. Carbon-SO3H catalyzed expedient synthesis of new spiro-[indeno [1, 2-b] quinoxaline-[11, 2′]-thiazolidine]-4′-ones as biologically important scaffold. Synth. Commun. 49, 80–93 (2019).

Hamzehloueian, M. et al. Synthesis, antibacterial and anticancer activities evaluation of new 4-thiazolidinone-indolin-2-one analogs. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 12, 8094–8104 (2022).

Flefel, E. M., El-Sofany, W. I., Awad, H. M. & El-Shahat, M. First synthesis for bis-spirothiazolidine derivatives as a novel heterocyclic framework and their biological activity. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 20, 152–160 (2020).

Bawazir, W. A. B. Synthesis of some new thioethers and 4-thiazolidinones bearing 3-(pyridine-4′-yl)-1, 2, 4-triazino [5, 6-b] indole moiety as antifungal agents. Int. J. Org. Chem.stry 9, 37–46 (2019).

Deshmukh, A. R. et al. Dicationic liquid mediated synthesis of tetrazoloquinolinyl methoxy phenyl 4-thiazolidinones and their antibacterial and antitubercular evaluation. Synth. Commun. 49, 587–601 (2019).

Shetty Chaithra, R. et al. Conventional and microwave synthesis and antioxidant evaluation of benzothiazole substituted 4-thiazolidinones. Indian Drugs 57(10), 17–22 (2020).

Valluri, K. K., Allaka, T. R., Viswanath, I. & Nagaraju, P. Design, molecular docking studies of oxaprozin linked to 4-thiazolidinone derivatives as a potent anticancer, analgesic and antiinflammatory agents. Asian J. Res. Chem. 11, 617–627 (2018).

Mishchenko, M., Shtrygol, S., Kaminskyy, D. & Lesyk, R. Thiazole-bearing 4-thiazolidinones as new anticonvulsant agents. Sci. Pharm. 88, 16 (2020).

Singh, J., Chawla, P. A., Bhatia, R. & Singh, S. 2, 5-disubstituted-4-thiazolidinones: Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, free radical scavenging potentials and structural insights through molecular docking. Lett. Org. Chem. 18, 957–968 (2021).

Deshmukh, A. R. et al. New tetrazoloquinolinyl methoxyphenyl-4-thiazolidinones: Synthesis and antihyperglycemic evaluation. Res. Chem. Intermed. 43, 1107–1120 (2017).

Srivastava, S. K., Srivastava, S. & Srivastava, S. D. Synthesis of 5‐arylidene‐2‐aryl‐3‐(1,2,4‐triazoloacetamidyl)‐1,3‐thiadiazol‐4‐ones as antibacterial, antifungal, analgesic and diuretic agents. ChemInform https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.200302109 (2003).

Diurno, M. V. et al. Synthesis and antihistaminic activity of some thiazolidin-4-ones. J. Med. Chem. 35, 2910–2912 (1992).

Shingalapur, R. V., Hosamani, K. M., Keri, R. S. & Hugar, M. H. Derivatives of benzimidazole pharmacophore: Synthesis, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic and DNA cleavage studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 1753–1759 (2010).

Flefel, E. M., El-Sofany, W. I., Al-Harbi, R. A. & El-Shahat, M. Development of a novel series of anticancer and antidiabetic: Spirothiazolidines analogs. Molecules 24, 2511 (2019).

Eleftheriou, P. et al. Fragment-based design, docking, synthesis, biological evaluation and structure–activity relationships of 2-benzo/benzisothiazolimino-5-aryliden-4-thiazolidinones as cycloxygenase/lipoxygenase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 47, 111–124 (2012).

Lesyk, R. B. et al. Thiazolidinone motif in anticancer drug discovery. Experience of DH LNMU medicinal chemistry scientific group. Biopolymers and Cell (2011).

Nirwan, S., Chahal, V. & Kakkar, R. Thiazolidinones: Synthesis, reactivity, and their biological applications. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 56, 1239–1253 (2019).

Azizi, N. & Haghayegh, M. S. Greener and additive-free reactions in deep eutectic solvent: One-pot, three-component synthesis of highly substituted pyridines. ChemistrySelect 2, 8870–8873 (2017).

Edrisi, M. & Azizi, N. Sulfonic acid-functionalized graphitic carbon nitride composite: a novel and reusable catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of polysubstituted pyridine in water under sonication. J. Iranian Chem. Soc. 17, 901–910 (2020).

Du, L. et al. Cascade 8π electrocyclization/benzannulation to access highly substituted phenylpyridines. Org. Lett. 23, 7966–7971 (2021).

Emam, H. E., El-Shahat, M., Hasanin, M. S. & Ahmed, H. B. Potential military cotton textiles composed of carbon quantum dots clustered from 4–(2, 4–dichlorophenyl)–6–oxo–2–thioxohexahydropyrimidine–5–carbonitrile. Cellulose 28, 9991–10011 (2021).

Allochio Filho, J. F., Lemos, B. C., de Souza, A. S., Pinheiro, S. & Greco, S. J. Multicomponent Mannich reactions: General aspects, methodologies and applications. Tetrahedron 73, 6977–7004 (2017).

Maddila, S., Jonnalagadda, S. B., Gangu, K. K. & Maddila, S. N. Recent advances in the synthesis of pyrazole derivatives using multicomponent reactions. Curr. Org. Synth. 14, 634–653 (2017).

Wan, J.-P., Gan, L. & Liu, Y. Transition metal-catalyzed C-H bond functionalization in multicomponent reactions: A tool toward molecular diversity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15, 9031–9043 (2017).

Ibarra, I. A., Islas-Jácome, A. & González-Zamora, E. Synthesis of polyheterocycles via multicomponent reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 1402–1418 (2018).

Patil, P. et al. Library-to-library synthesis of highly substituted α-aminomethyl tetrazoles via Ugi reaction. ACS Comb. Sci. 20, 70–74 (2018).

Pathoor, R. & Bahulayan, D. MCR-click synthesis, molecular docking and cytotoxicity evaluation of a new series of indole–triazole–coumarin hybrid peptidomimetics. New J. Chem. 42, 6810–6816 (2018).

Ezzatzadeh, E. & Hossaini, Z. Green synthesis and antioxidant activity of novel series of benzofurans from euparin extracted of Petasites hybridus. Nat. Prod. Res. 33, 1617–1623 (2019).

Sathiyachandran, P., Manogaran, P., Nesterov, V. N., Padma, V. V. & Prasad, K. J. R. Design and synthesis of novel pyrrolo [2, 3-a] carbazoles: 7-Chloro-2-oxo-3a-(2′-oxo-2′, 3′-dihydro-1′ H-indol-3′-yl)-2, 3, 3a, 4, 5, 10-hexahydro-pyrrolo [3, 2-a] carbazole-1-carbonitrile as an efficient anticancer agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 150, 851–863 (2018).

Sonawane, H. R., Deore, J. V. & Chavan, P. N. Reusable nano catalysed synthesis of heterocycles: An overview. ChemistrySelect 7, e202103900 (2022).

Gawande, M. B., Branco, P. S. & Varma, R. S. Nano-magnetite (Fe3O4) as a support for recyclable catalysts in the development of sustainable methodologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 3371–3393 (2013).

Roy, S. & Pericas, M. A. Functionalized nanoparticles as catalysts for enantioselective processes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 2669–2677 (2009).

Firouzabadi, H., Iranpoor, N., Gholinejad, M. & Hoseini, J. Magnetite (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles-catalyzed Sonogashira-Hagihara reactions in ethylene glycol under ligand-free conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 353, 125–132 (2011).

Martinez, R., Ramon, D. J. & Yus, M. Unmodified nano-powder magnetite catalyzes a four-component aza-sakurai reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350, 1235–1240 (2008).

Shirini, F. & Abedini, M. Application of nanocatalysts in multi-component reactions. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 4838–4860 (2013).

Wang, D. & Astruc, D. Fast-growing field of magnetically recyclable nanocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 114, 6949–6985 (2014).

Abbass, E. M. et al. Rational design and eco-friendly one-pot multicomponent synthesis of novel ethylidenehydrazineylthiazol-4 (5H)-ones as potential apoptotic inducers targeting wild and mutant EGFR-TK in triple negative breast cancer. Bioorg. Chem. 142, 106936 (2024).

Abbass, E. M., Ali, A. K., El-Farargy, A. F., Abdel-Haleem, D. R. & Shaban, S. S. Synthesis, toxicological and in silico evaluation of novel spiro pyrimidines against Culex pipiens L. referring to chitinase enzyme. Sci. Rep. 14, 1516 (2024).

Dixit, V., Kumar, G., Kumar, P., Soni, A. & Nemiwal, M. Emerging strategies for synthesis of heterocyclic compounds enabled by titanium oxide nanoparticles as heterogeneous catalyst. Tetrahedron 160, 134039 (2024).

Veisi, H. et al. Recent advances in the application of magnetic nanocatalysts in multicomponent reactions. RSC Adv. 13, 20530–20556 (2023).

Allen, F. H. & Bruno, I. J. Bond lengths in organic and metal-organic compounds revisited: X—H bond lengths from neutron diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 66, 380–386 (2010).

Allen, F., Watson, D., Brammer, L., Orpen, A. & Taylor, R. Typical interatomic distances: Organic compounds. Int. Tables Crystallogr. 100, 790–811 (2006).

Shruthi, C. et al. Molecular structure, Hirshfeld surface and density functional theoretical analysis of a NLO active chalcone derivative single crystal—a quantum chemical approach. J. Mol. Struct. 1228, 129739 (2021).

Spackman, P. R. et al. CrystalExplorer: A program for Hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 54, 1006–1011 (2021).

Chandini, K., Khadri, M. N., Amoghavarsha, N., Sridhar, M. & Khanum, S. A. Synthesis, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, energy frameworks and computational studies of Schiff base derivative. Heliyon 8, e10047 (2022).

Barnes, E. C., Petersson, G. A., Montgomery, J. A. Jr., Frisch, M. J. & Martin, J. M. Unrestricted coupled cluster and Brueckner doubles variations of W1 theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2687–2693 (2009).

Ramadan, R. et al. Spectroscopic, DFT, non-linear optical properties and in vitro biological studies of Co (II), Ni (II) and Cu (II) complexes of hydrazide Schiff base derivatives. Appl. Organometal. Chem., e6246 (2021).

Elantabli, F. M., El-Medani, S. M., Kozakiewicz-Piekarz, A. & Ramadan, R. M. New transition metal complexes of 1-phenyl-2-((quinolin-2-ylmethylene) amino) ethan-1-ol Schiff base: Spectroscopic, X-ray, DFT, Hirshfeld surface analysis, biological, and molecular docking studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 36, e6779 (2022).

El-Medani, S. M. et al. Spectroscopic, crystal structural, theoretical and biological studies of phenylacetohydrazide Schiff base derivatives and their copper complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 1208, 127860 (2020).

Hassen, S., Chebbi, H., Zid, M. & Arfaoui, Y. Assembly and weak interactions in the crystal structure of 2-amino-4-(3-bromophenyl)-1, 3, 5-triazinobenzimidazolium chloride studied by X-ray diffraction, vibrational spectroscopy, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DFT calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 1179, 678–684 (2019).

Ramadan, R. M., Noureldeen, A. F., Abo-Aly, M. M. & El-Medani, S. M. Spectroscopic, DFT analysis, antimicrobial and cytotoxicity studies of three gold(III) complexes. Inorgan. Nano-Met. Chem. 52, 213–225 (2022).

Ghani, N. T. A. & Mansour, A. M. Structural and in vitro cytotoxicity studies on 1H-benzimidazol-2-ylmethyl-N-phenyl amine and its Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 81, 529–543 (2011).

Guha, R. On exploring structure–activity relationships. In In Silico Models for Drug Discovery (ed. Kortagere, S.) 81–94 (Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-62703-342-8_6.

Brock, T. D., Madigan, M. T., Martinko, J. M. & Parker, J. Brock Biology of Microorganisms (Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River (NJ), 2003).

Ramadan, R. M. & Noureldeen, A. F. H. Molecular docking and drug design of Schiff base metal complexes. In Structural and Biological Applications of Schiff Base Metal Complexes (eds Jain, P. & Singh, P.) (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2023).

Abbass, E. M., Khalil, A. K., Abdel-Mottaleb, Y. & Abdel-Mottaleb, M. S. Exploiting modeling studies for evaluating the potential antiviral activities of some clinically approved drugs and herbal materials against SARS-CoV-2: Theoretical studies toward hindering the virus and blocking the human cellular receptor. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 44, 1209–1220 (2024).

Anwer, K. E., Hamza, Z. K. & Ramadan, R. M. Synthesis, spectroscopic, DFT calculations, biological activity, SAR, and molecular docking studies of novel bioactive pyridine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13, 15598 (2023).

Anwer, K. E., Sayed, G. H. & Ramadan, R. M. Synthesis, spectroscopic, DFT calculations, biological activities and molecular docking studies of new isoxazolone, pyrazolone, triazine, triazole and amide derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 1256, 132513 (2022).

CrysAlisPro, (Oxford Diffraction/Agilent Technologies UK Ltd, Yarnton, England)

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. Sect. A Found. Adv. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Cottrell, S. J. et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr 53, 226–235 (2020).

Anwer, K. E., Sayed, G. H., Kozakiewicz-Piekarz, A. & Ramadan, R. M. Novel annulated thiophene derivatives: Synthesis, spectroscopic, X-ray, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT, biological, cytotoxic and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1276, 134798 (2023).

Elantabli, F. M. et al. Structural investigations of new tridentate-phenylacetohydrazide Schiff base metal chelates: X-ray diffraction, Hirshfeld surface analyses, DFT, antibacterial and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1299, 137230 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2024-2985-08”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M.A. Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Writing original draft. and A.E. Investigation, Revised original draft. and A.K. A. Data curation, Revising original and final draft. and A.F.E Methodology, Data curation. and A.K. Methodology, Data curation, Software. and R.M.R. Validation, Software, Writing, review and editing final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbass, E.M., El-Rayyes, A., Khalil Ali, A. et al. Catalyzed syntheses of novel series of spiro thiazolidinone derivatives with nano Fe2O3: spectroscopic, X-ray, Hirshfeld surface, DFT, biological and docking evaluations. Sci Rep 14, 18773 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65282-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65282-z