Abstract

Gut fungal imbalances, particularly increased Candida spp., are linked to obesity. This study explored the potential of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum cell-free extracts (postbiotics) to modulate the growth of Candida albicans and Candida kefyr, key members of the gut mycobiota. A minimal synthetic gut model was employed to evaluate the effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum postbiotics on fungal growth in mono- and mixed cultures. Microreactors were employed for culturing, fungal growth was quantified using CFU counting, and regression analysis was used to evaluate the effects of postbiotics on fungal growth. Postbiotics at a concentration of 12.5% significantly reduced the growth of both Candida species. At 24 h, both C. albicans and C. kefyr in monocultures exhibited a decrease in growth of 0.11 log CFU/mL. In contrast, mixed cultures showed a more pronounced antifungal effect, with C. albicans and C. kefyr reductions of 0.62 log CFU/mL and 0.64 log CFU/mL, respectively. Regression analysis using the Gompertz model supported the antifungal activity of postbiotics and revealed species-specific differences in growth parameters. These findings suggest that L. plantarum postbiotics have the potential to modulate the gut mycobiota by reducing Candida growth, potentially offering a therapeutic approach for combating fungal overgrowth associated with obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gut microbiota is a complex ecosystem of microorganisms residing in the human gastrointestinal tract. This ecosystem significantly impacts the physiological health and overall wellness of the host. While bacteria have long dominated microbiome research due to their abundance and well-established roles in digestion, metabolism, immunity, and brain function1, fungi are emerging as crucial players in this delicate ecosystem, with potential implications for health and disease. The gut mycobiota, encompassing diverse fungal species like Candida and Saccharomyces, has garnered increasing attention for its impact on various physiological processes2. Within this complex community, microbial interactions shape the growth dynamics and functionality of the gut ecosystem. These interactions are influenced by various factors like diet, age, genetics, and disease states3. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, a prominent bacterial resident, plays a significant role in shaping the intestinal community by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetic, propionic, and butyric acids4. In a recent study assessing the fungal species within the intestinal mycobiota of subjects with obesity, a higher abundance of Candida albicans and Candida kefyr was detected among individuals with obesity compared to those with a healthy weight; additionally, these fungal species exhibited a positive correlation with weight gain parameters, such as body mass index and percentage of fat mass, indicating an association with increased adiposity2. Other studies have correlated the elevated abundance of Candida spp. with intestinal dysbiosis5,6. The presence of postbiotics, bioactive molecules secreted by probiotic bacteria, frequently governs microbial interactions within the human gut microbiota. It has also been reported that these postbiotics have antimicrobial effects against pathogenic species in the human intestinal microbiota7. SCFAs, amongst these postbiotics, play a critical role in mediating communication between the host and the gut microbiota, influencing the gut ecosystem by driving the selective enrichment of specific bacterial populations or the decline in the growth of other gut microbes1. Consequently, studying the interplay between probiotic-mediated metabolite exchange, like SCFAs, and microbial interactions, including those involving intestinal yeasts, is crucial for maintaining a stable and functional gut ecosystem1,8.

In vitro models are valuable for studying microbial growth dynamics within the human gut microbiota. These models offer several advantages, including rapid evaluation of diverse substrates, experimental reproducibility, reduced costs, and ethical considerations9. Recently, synthetic communities (SynComs) have been designed to mimic and model the specific compositions and responses of a portion of the gut microbiome10; these SynComs are laboratory-designed communities that facilitate controlled studies of specific species and their influence on the ecosystem function11. SynComs encompass a varying number and proportions of species, with a minimum of two required for studying growth dynamics10,12. Integrating these models with mathematical tools like regression analysis deepens our understanding of these dynamics in a quantitative manner, particularly those involving antimicrobial effects13,14. This combined approach provides a comprehensive picture of the gut’s complex microorganism-spanning processes. This knowledge is crucial to harnessing the metabolic potential of the gut microbiota and mycobiota and identifying key taxa. It empowers us to modulate gut microbiota composition and function across diverse scenarios15.

The widespread use of antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents can significantly disrupt the balance of the human gut mycobiota, leading to dysbiosis and associated health consequences. Understanding the antimicrobial properties of microbial metabolites, including postbiotics, holds immense potential for developing alternative strategies to combat pathogenic infections, modulate the gut microbiota and mycobiota, and promote overall health16. This study aims to investigate the potential antimicrobial effects of L. plantarum postbiotics within a minimal synthetic model of the human gut mycobiota, providing insights into their potential role in maintaining a healthy microbial balance and fostering gut health.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms’ selection and culture conditions

Candida albicans ATCC 10231 and Candida kefyr ATCC 2512 were used as fungal microorganisms to represent a SynCom mimicking the intestinal mycobiota associated with obesity2. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp-115 was the probiotic bacterium used for postbiotic extraction. C. albicans and C. kefyr were cultured in YPD medium (Yeast extract-peptone-dextrose), while L. plantarum was cultured in Difco™ MRS medium (De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe). SynCom cultures were incubated under aerobic conditions at 37 °C with continuous shaking at 100 rpm.

Growth kinetics of Candida spp.

A flask containing 100 mL of fresh YPD medium was inoculated with 2 mL of a 16-h culture from each yeast, reaching an initial optical density of 0.2 at 595 nm. Subsequently, each culture was aseptically distributed into 63 microbioreactors (2 mL capacity Eppendorf-type plastic vials), each receiving 1 mL of the culture. These 63 microbioreactors served as data points for the study of the 24-h growth kinetics. The microbioreactor vials were then incubated at 37 °C and 100 rpm. The growth kinetics of the microbial cultures were evaluated by measuring the microbial concentration in colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) and the optical density of the samples. Samples were collected every hour for the first 16 h, followed by collections every 2 h until the experiment ended at 24 h. Each vial containing spent medium was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C (1580R, Gyrozen). The sediment was resuspended in 1 mL of sterile peptone water (BD) to measure the optical density at 595 nm. After measuring the optical density, plate culturing was performed using the drop plate method, as described by Naghili et al. Serial dilutions were performed in peptone water using the resuspended sample, with each sample being subjected to 1:10 serial dilutions. Subsequently, 10 µL of the final dilution of each sample was aseptically spread on Petri dishes previously prepared with YPD agar for microbial growth. The Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h17.

L. plantarum culture and extraction of postbiotics

L. plantarum postbiotics were obtained following the methodology described by García-Gamboa et al. (2022)18. L. plantarum was incubated in MRS broth at 37 °C and 100 rpm for 16 h. After incubation, the culture medium was centrifuged at 2800×g for 10 min at 4 °C to isolate the postbiotics. The supernatant was filtered through a sterile 0.45 μm pore size filter (Corning®, NY, USA) and stored at 4 °C.

Determining the dose and impact of postbiotics on Candida spp. growth

The minimum effective concentration (MEC) of L. plantarum postbiotics against Candida spp. was determined to select the appropriate dose for the subsequent yeast growth kinetics assay in mono and mixed cultures. C. albicans and C. kefyr were cultivated in YPD broth at 37 °C for 24 h. Cultures were then standardized to an optical density of 0.2 at 595 nm, corresponding to 1 × 105 CFU/mL. Two milliliters of each culture were added to separate flasks containing 50 mL of fresh YPD broth. Then, 1 mL aliquots were transferred to microbioreactors. Postbiotics were added to the Candida cultures (C. albicans and C. kefyr separately) to achieve concentrations of 12.5%, 25%, and 50%. A separate culture of each Candida species without postbiotics was used as a control. Cultures were incubated in triplicate at 37 °C and 100 rpm for 8 h. Growth inhibition of Candida spp. was monitored by measuring the optical density at 595 nm every hour18.

Evaluation of postbiotic antimicrobial effects on Candida spp. monocultures and mixed cultures

This study investigated the impact of postbiotics on the growth of Candida albicans and Candida kefyr, both in mono and mixed cultures. A fixed concentration of 12.5% L. plantarum postbiotics was employed for monoculture and mixed culture experiments. For monoculture experiments, growth kinetics was assessed following the methodology described in the ‘Growth kinetics of Candida spp.’ section, adding 12.5% postbiotics to the growth medium for the respective Candida species. For mixed culture experiments, a new flask containing 100 mL fresh YPD medium was inoculated with 2 mL (OD 0.2 at 595 nm) of each 16-h culture from C. albicans and C. kefyr. The inoculated culture was aseptically distributed into 63 microbioreactors that represent the triplicates of the 24-h cultures. Microbioreactors from monoculture and mixed cultures were incubated at 37 °C and 100 rpm. Samples were collected hourly until hour 16, then every 2 h thereafter until the end of the experiment at 24 h. Microbial concentration was determined by CFU/mL using the drop plate method. Samples from monocultures were plated on YPD agar and samples obtained from mixed cultures were plated on BD ChromaAgar, a selective medium that differentiates Candida species by color. Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Additionally, the pH of the postbiotics and Candida cultures (mono and mixed) was measured using a pH meter HI 2210 (Hanna Instruments).

Modeling the growth kinetics of Candida spp.

To assess the antimicrobial effect of postbiotics, we analyzed the experimental data comprising the mean growth [CFU/mL] of Candida spp. across the eight distinct trials. The regression analysis of the data was subjected to fitting with a sigmoidal growth model, the four-parameter Gompertz model represented by Eq. (1). Gompertz model has proved an appropriate response to represent growth in batch culture processes19, it was implemented for numerical calculation using the Curve Fitting App available in MATLAB 2023b (Math-Works):

This model, renowned for its utility in microbial growth analysis20, offers a comprehensive framework: a signifies the maximum fungal concentration, b correlates with the maximum growth rate, c denotes the termination of the lag phase, and d represents the initial concentration. We performed the regression analysis in each dataset, allowing for a comparative assessment of the set of parameters and values and the coefficients of determination R-squared. To accurately model the growth kinetics of each culture, data points for regression analysis were limited to the stationary phase, representing the sigmoidal growth pattern, determining the end of the stationary phase by calculating the second derivative to identify the inflection point of the concentration rate of change. Additionally, we derive the confidence interval (95%) for the models based on the identified parameters.

Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate, with analytical data expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data were statistically analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test using GraphPad Prism version 8.

Results

Evaluation of the impact of postbiotics on yeast growth at different doses

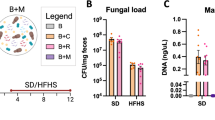

Postbiotics were obtained from the L. plantarum culture cultivated in an MRS medium until the stationary phase (16 h) was concluded to encompass the entire spectrum of metabolites secreted by the probiotic throughout its growth cycle. Afterward, the culture underwent centrifugation and filtration to ensure that the postbiotics were devoid of cells. The initial (6.50 ± 0.01) and final (3.96 ± 0.01) pH of the postbiotics are shown in Table 1. Before assessing the antimicrobial efficacy of postbiotics in monoculture and mixed cultures, we determined the minimum effective concentration (MEC) of three concentrations of L. plantarum postbiotics (12.5%, 25%, and 50%). All three concentrations exhibited significant reductions in the growth of both C. albicans and C. kefyr compared to the untreated control (p < 0.05), as determined by optical density measurements (Fig. 1). The 12.5% dose demonstrated antifungal activity against C. albicans and C. kefyr, respectively (p < 0.001). Absorbance data at 8 h showed a significant decrease in the growth of C. albicans treated with the 12.5% dose (OD = 0.74 ± 0.10) in contrast to the control (OD = 1.04 ± 0.01; p < 0.05). This corresponds to a reduction of 0.15 log CFU/mL (Table S1) based on a pre-established calibration curve relating absorbance to cell density. C. kefyr treated with the 12.5% postbiotic dose exhibited a significant decrease in absorbance (OD = 1.53 ± 0.04) compared to the control group (OD = 1.88 ± 0.04; p < 0.05). This corresponds to a reduction of 0.10 log CFU/mL. Consequently, the postbiotic concentration of 12.5% was chosen for subsequent experiments exploring its effects on monoculture and mixed cultures of Candida spp. in the minimal synthetic model of the intestinal mycobiota.

Effects of postbiotics on Candida spp. growth and pH in mono- and mixed cultures

The growth kinetics of C. albicans and C. kefyr in monocultures and mixed cultures, with and without postbiotics, are presented in Supplementary Material (Tables S2 and S3, respectively). Initial inoculum concentrations ranged from 5.51 to 5.69 log CFU/mL for both fungal species, with no significant differences (p < 0.05) between the control and postbiotic groups. In monocultures, C. albicans reached a maximum growth stationary phase at hour 14 (6.95 ± 0.01 log CFU/mL) without postbiotics, whereas its growth with postbiotics peaked at hour 20 (6.82 ± 0.01 log CFU/mL). C. kefyr achieved a maximum growth at hour 14 (7.66 ± 0.02 log CFU/mL) without postbiotics, while cultures with postbiotics exhibited a maximum growth at the same 14 h (7.54 ± 0.03 log CFU/mL). The growth patterns of Candida spp. in mixed cultures differed from those observed in monocultures. C. albicans in mixed cultures without postbiotics exhibited maximum growth at hour 11 (6.65 ± 0.01 log CFU/mL). The mixed culture with postbiotics showed a higher C. albicans growth (6.40 ± 0.02 log CFU/mL) at hour 13 (p < 0.05). Similarly, C. kefyr showed a maximum growth at hour 15 (7.20 ± 0.05 log CFU/mL and 7.16 ± 0.03 log CFU/mL, respectively, for cultures without and with postbiotics compared to control (p < 0.05). Both yeasts exhibited decreased growth in mixed cultures compared to the experiment in single cultures. C. albicans counts were 0.32 and 0.62 log CFU/mL lower in mixed culture after 24 h with and without postbiotics, respectively, while C. kefyr counts were 0.49 and 0.64 log CFU/mL lower with and without postbiotics. Both mono- and mixed cultures of Candida spp. exhibited a lower initial pH at zero hours (around 5.53–5.58) in the presence of postbiotics compared to cultures without postbiotics (around 6.30–6.32) (Table 1). Despite these initial differences, all cultures showed a similar decrease in pH by hour 24. Cultures without postbiotics exhibited a 0.69–0.73 pH reduction, while cultures with postbiotics showed a 0.67–0.69 pH reduction.

Mathematical modeling of the growth kinetics of Candida spp.

The identified parameters for each regression are presented in Table 2, along with their respective R-squared value. Based on these values, we can determine that this model was a good fit for the data as it was greater than 0.99 in most cases. The graphical representation of these regression models can be observed in Fig. 2., divided by type of culture and species. This analysis confirms what was observed with the fungal cell count, that postbiotics have an inhibitory effect in the growth of both species, regardless of the culture type, as observed when comparing the value of the maximum population (parameter a). In mixed cultures, both without and with postbiotics, significant differences were observed in the maximum population for both C. albicans and C. kefyr (4.5E + 06 and 2.5E + 06 CFU/mL, respectively, for Candida albicans; 1.6E + 07 and 1.45E + 07 CFU/mL, respectively, for C. kefyr) (p < 0.05). The impact on the maximum growth rate, denoted by (parameter b), differed within the C. albicans cultures. During monoculture with postbiotics, this parameter exhibited a decrease (0.21 CFU/mL/h). In contrast, in mixed culture without postbiotics, it showed an increase (0.48 CFU/mL/h), indicating a significant statistical difference compared to the control (0.34 CFU/mL/h) (p < 0.05). Notably, it is important to remark that the culture without postbiotics alongside C. kefyr was beneficial in this parameter for C. albicans. Conversely, C. kefyr in monoculture showed no significant change with or without postbiotics. However, in the mixed culture with postbiotics, it decreased the maximum growth rate (0.33 CFU/mL/h, compared to the control’s 0.39 CFU/mL/h, p < 0.05).

Postbiotics affected the lag phase duration (parameter c) of Candida spp. In mixed cultures, C. albicans experienced a shortened lag phase (reduced by 1.03 and 0.23 h in the cultures without and with postbiotics, respectively, although not statistically significant). Conversely, lag phase duration was prolonged for C. kefyr in both mono- and mixed cultures with postbiotics (p < 0.05). Specifically, the increase in lag phase for C. kefyr was 1.29 h in monoculture with postbiotics and 1.95 and 1.85 h in mixed cultures without and with postbiotics, respectively. Further analyzing the results from the regressions, specifically the 95% confidence interval for prediction of the parameters, for the case of C. albicans, it can be determined that for the monoculture, the growth kinetics can be modeled differentially up to 6.8 experimental hours. For previous time points, the models overlap (Fig. 3a); however, during mixed culture, this time came earlier at 4 h (Fig. 3b). This allows us to infer that the ecological interactions during mixed culture accelerate the antimicrobial effect of postbiotics compared to monocultures for this species. In the case of C. kefyr, clear differences are evident during monoculture, beginning as early as experimental hour 2.2. However, the model overlaps during the experiment duration for the mixed culture (Figures S1a and S1b). This indicates that ecological interactions play a major role in the effect that postbiotics will exert on this species.

Discussion

This study explored the potential application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum postbiotics as antifungal agents against Candida albicans and Candida kefyr, key members of the human gut mycobiota. We employed a minimal gut model with these two yeasts relevant to obesity. Changes in the composition of the gut mycobiota, particularly an increase in Candida spp., have been linked to various pathologies and intestinal dysbiosis21. Recent studies have shown alterations in the gut mycobiota of obese individuals, with a rise in C. albicans and C. kefyr species potentially contributing to obesity development2,22. The potential pathogenic role of Candida spp. in obesity has also been explored, with their high prevalence and association with fungal dysbiosis being implicated23. The diverse Candida species in the intestinal microbiota possess a variety of enzymes that act as potent virulence factors, enabling them to survive and thrive. These enzymes, including phospholipase, esterase, proteinase, caseinolytic protease, hemolysin, and coagulase, facilitate host cell damage, nutrient acquisition, and immune system evasion24.

Furthermore, administering specific probiotics like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium or their postbiotics may help restore intestinal microbiota balance and control Candida spp. overgrowth25,26. L. plantarum, for instance, has effectively inhibited the growth of various prokaryotic intestinal pathogens, including Helicobacter pylori, Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Clostridium difficile27. The findings of this study, where L. plantarum postbiotics inhibited C. albicans and C. kefyr, align with previous research indicating their ability to suppress the growth of yeast-like intestinal pathogens such as Candida spp28. The production of lactic acid, short-chain fatty acids such as acetic, propionic, and butyric acids (expected at concentrations of approximately 13.43, 1.75, 0.23, and 1.85 mM, respectively)29, and bacteriocins like plantaricins by L. plantarum, has been linked to this inhibitory effect against Candida spp. and other intestinal pathogens30.

Susceptibility to antifungals varies among Candida species. In this study, the observed difference in susceptibility between C. albicans and C. kefyr to L. plantarum postbiotics may be related to possible species-specific mechanisms of action and interactions between the species when co-cultured. Our findings demonstrate promising antifungal activity of postbiotics against Candida spp., particularly in co-culture, suggesting their potential role in modulating the intestinal fungal community. The observed decrease in growth of both Candida species in mixed cultures compared to monocultures could be attributed to competition for nutrients, production of specific antimicrobial compounds by the microorganisms, or other mechanisms related to the phenomenon of ‘resistance to colonization’23. Furthermore, some Candida species exhibit a reduced capacity to develop biofilms when co-cultured, which may contribute to their greater susceptibility to antimicrobials31,32,33, along with competition and potential antimicrobial production. It is essential to highlight these aspects, as in the intestinal microbiota, microbe-microbe and microbe-host interactions develop, meaning interactions depend not only on the growth of a single microorganism but also on interaction with the entire intestinal environment. Hence, using minimal synthetic intestinal models is crucial for evaluating the antimicrobial effect of L. plantarum postbiotics against gut pathogens. These models allow monitoring of microbial growth while considering the interactions of a minimal set of assembled species representing a human gut ecological niche34.

The regression analysis revealed high R-squared values observed across most conditions, indicating a robust fit of the Gompertz model to the experimental data concerning the growth dynamics of Candida spp.35. This aligns with the previous work of Guo et al.36, where the Gompertz model effectively described microbial growth in the gut microbiota. Postbiotics consistently demonstrated inhibitory effects on both fungal species, as reflected by lower values of the maximum population, irrespective of the culture type, thereby emphasizing the potential antifungal properties of postbiotics against Candida spp.37. Postbiotics significantly modulated microbial growth, extending the lag phase in C. kefyr monocultures and mixed cultures. This delayed onset of growth could be due to physiological adaptations required to cope with suboptimal conditions or the need to adapt to a new environment38. These lag phase adaptations are likely linked to the development of tolerance mechanisms in response to the antimicrobial stress imposed by postbiotics39. The observed lag phase differences between C. kefyr and C. albicans suggest differential interactions between postbiotics and Candida species, possibly influenced by culture conditions40. Postbiotics exhibited species-specific effects on maximum growth rate35. In C. albicans monoculture, they caused a decrease, while for C. kefyr, the decrease was observed only in mixed culture, suggesting differential response mechanisms among Candida species41. Interestingly, in mixed cultures without postbiotics, the presence of C. kefyr positively influenced C. albicans growth rate, suggesting potential interactions between these fungal species42.

Recognizing the limitations of this study, we used a simplified in vitro minimal synthetic model with only two fungal species from the human gut microbiota. Future research should utilize more intricate synthetic models to strengthen our antifungal observations and explore a broader spectrum of inhibitory properties, such as biofilm inhibition against Candida species. These models should incorporate a wider diversity of gut microbiota, including relevant bacterial species, and mimic the gut’s anaerobic environment. Additionally, elucidating the specific mechanisms by which postbiotics exert their activity remains a crucial area for further investigation. One approach to explore these interactions further is by incorporating models like Lotka-Volterra to analyze the specific types of ecological interspecies interactions (e.g., competition, commensalism) developing between C. albicans and C. kefyr.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study explored the potential of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum postbiotics to inhibit the growth of Candida albicans and Candida kefyr, fungal members of the gut microbiota associated with obesity. Using a minimal gut model, we found that postbiotics reduced the growth of both yeasts. In monocultures, the reduction was 0.11 log CFU/mL for both C. albicans and C. kefyr. The postbiotics exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect on the yeasts in mixed cultures, reducing their growth by 0.62 log CFU/mL and 0.64 log CFU/mL for C. albicans and C. kefyr respectively. These findings suggest that postbiotics could be beneficial in modulating the gut fungal community and combating fungal overgrowth associated with obesity. The Gompertz model effectively captured the growth dynamics of Candida spp., with postbiotics consistently demonstrating inhibitory effects.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SCFA:

-

Short-chain fatty acids

- SynComs:

-

Synthetic communities

- CFU:

-

Colony forming units

- OD:

-

Optical density

- YPD:

-

Yeast extract-peptone-dextrose

- MRS:

-

De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe

- MEC:

-

Minimum effective concentration

References

Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 1–28 (2022).

García-Gamboa, R. et al. The intestinal mycobiota and its relationship with overweight, obesity and nutritional aspects. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 34, 645–655 (2021).

Salazar, J. et al. Exploring the relationship between the gut microbiota and ageing: A possible age modulator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 5845 (2023).

Magryś, A. & Pawlik, M. Postbiotic fractions of probiotics Lactobacillus plantarum 299v and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG show immune-modulating effects. Cells 12, 2538 (2023).

Kreulen, I. A. M., de Jonge, W. J., van den Wijngaard, R. M. & van Thiel, I. A. M. Candida spp. in human intestinal health and disease: More than a gut feeling. Mycopathologia 188, 845–862 (2023).

Bertolini, M. et al. Candida albicans induces mucosal bacterial dysbiosis that promotes invasive infection. PLoS Pathogens 15, e1007717 (2019).

Mayorgas, A., Dotti, I. & Salas, A. Microbial metabolites, postbiotics, and intestinal epithelial function. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 65, 2000188 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between intestinal microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 5, 311–322 (2022).

González, A., Conceição, E., Teixeira, J. A. & Nobre, C. In vitro models as a tool to study the role of gut microbiota in obesity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2023.2232022 (2023).

van Leeuwen, P. T., Brul, S., Zhang, J. & Wortel, M. T. Synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) of the human gut: Design, assembly, and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 47, fuad012 (2023).

Vrancken, G., Gregory, A. C., Huys, G. R. B., Faust, K. & Raes, J. Synthetic ecology of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 754–763 (2019).

Venturelli, O. S. et al. Deciphering microbial interactions in synthetic human gut microbiome communities. Mol. Syst. Biol. 14, e8157 (2018).

Remien, C. H., Eckwright, M. J. & Ridenhour, B. J. Parameter identifiability of the generalized lotka-volterra model for microbiome studies. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/463372 (2018).

Gutierrez-Vilchis, A., Perfecto-Avalos, Y. & Garcia-Gonzalez, A. Modeling bacteria pairwise interactions in human microbiota by Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy)*. in 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 1–4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC40787.2023.10341078.

Mabwi, H. A. et al. Synthetic gut microbiome: Advances and challenges. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 363–371 (2021).

Duan, H. et al. Antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis and barrier disruption and the potential protective strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 1427–1452 (2022).

Naghili, H. et al. Validation of drop plate technique for bacterial enumeration by parametric and nonparametric tests. Vet. Res. Forum. 4, 179–183 (2013).

García-Gamboa, R. et al. Anticandidal and antibiofilm effect of synbiotics including probiotics and inulin-type fructans. Antibiotics 11, 1135 (2022).

Korkmaz, M. A study over with four-parameter Logistic and Gompertz growth models. Numer. Methods Part. Differ. Equ. 37, 2023–2030 (2021).

Tjørve, K. M. C. & Tjørve, E. The use of Gompertz models in growth analyses, and new Gompertz-model approach: An addition to the unified-richards family. PLoS ONE 12, e0178691 (2017).

Matijašić, M. et al. Gut microbiota beyond bacteria—Mycobiome, Virome, Archaeome, and eukaryotic parasites in IBD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2668 (2020).

Peroumal, D., Sahu, S. R., Kumari, P., Utkalaja, B. G. & Acharya, N. Commensal fungus Candida albicans maintains a long-term mutualistic relationship with the host to modulate gut microbiota and metabolism. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e02462 (2022).

Shoukat, M. et al. Profiling of potential pathogenic candida species in obesity. Microb. Pathogen. 174, 105894 (2023).

Pandey, N., Gupta, M. K. & Tilak, R. Extracellular hydrolytic enzyme activities of the different Candida spp. isolated from the blood of the Intensive Care Unit-admitted patients. J. Lab. Physicians 10(04), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.4103/JLP.JLP_81_18 (2018).

Kunyeit, L., Anu-Appaiah, K. A. & Rao, R. P. Application of probiotic yeasts on candida species associated infection. J. Fungi 6(4), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6040189 (2020).

Rawal, S. & Ali, S. A. Probiotics and postbiotics play a role in maintaining dermal health. Food Funct. 14, 3966–3981 (2023).

Potočnjak, M. et al. Three new Lactobacillus plantarum strains in the probiotic toolbox against gut pathogen Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 55, 48–54 (2017).

Vazquez-Munoz, R. & Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A. Anticandidal activities by Lactobacillus species: An update on mechanisms of action. Front. Oral Health 2, 689382 (2021).

García-Gamboa, R. et al. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effect of inulin-type fructans, used in synbiotic combination with Lactobacillus spp. against Candida albicans. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 77, 212–219 (2022).

Abdulhussain Kareem, R. & Razavi, S. H. Plantaricin bacteriocins: As safe alternative antimicrobial peptides in food preservation—A review. J. Food Saf. 40, e12735 (2020).

Holcombe, L. J. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted factors impair biofilm development in Candida albicans. Microbiology 156, 1476–1486 (2010).

Nagy, F. et al. In vitro antifungal susceptibility patterns of planktonic and sessile Candida kefyr clinical isolates. Med. Mycol. 56, 493–500 (2018).

Ahmad, S. et al. Candida kefyr in Kuwait: Prevalence, antifungal drug susceptibility and genotypic heterogeneity. PLoS ONE 15, e0240426 (2020).

Berkhout, M., Zoetendal, E., Plugge, C. & Belzer, C. Use of synthetic communities to study microbial ecology of the gut. Microbiome Res. Rep. 1, 4 (2022).

Akın, E., Pelen, N. N., Tiryaki, I. U. & Yalcin, F. Parameter identification for gompertz and logistic dynamic equations. PLoS ONE 15, e0230582 (2020).

Guo, C. Y. et al. Dynamic change of the gastrointestinal bacterial ecology in cows from birth to adulthood. MicrobiologyOpen 9, e1119 (2020).

Rossoni, R. D. et al. The postbiotic activity of Lactobacillus paracasei 28.4 against Candida auris. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 397 (2020).

Păcularu-Burada, B., Georgescu, L. A., Vasile, M. A., Rocha, J. M. & Bahrim, G.-E. Selection of wild lactic acid bacteria strains as promoters of postbiotics in gluten-free sourdoughs. Microorganisms 8, 643 (2020).

Li, B., Qiu, Y., Shi, H. & Yin, H. The importance of lag time extension in determining bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Analyst 141, 3059–3067 (2016).

Spaggiari, L. et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, and L. reuteri cell-free supernatants inhibit candida parapsilosis pathogenic potential upon infection of vaginal epithelial cells monolayer and in a transwell coculture system in vitro. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e02696 (2022).

Divyashree, S., Shruthi, B., Vanitha, P. R. & Sreenivasa, M. Y. Probiotics and their postbiotics for the control of opportunistic fungal pathogens: A review. Biotechnol. Rep. 38, e00800 (2023).

Wambaugh, M. A. et al. Synergistic and antagonistic drug interactions in the treatment of systemic fungal infections. eLife 9, e54160 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Biosciences, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tecnológico de Monterrey Campus Guadalajara, for the academic support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: R.G.G. and A.G.G. were responsible for conceptualization, investigation, analysis, and writing. J.G.G. and M.J.A.C. were responsible for experimental procedures and methodology. Y.P.A. was involved in conceptualization, supervision, and critical review. A.G.V. performed the mathematical analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the articles Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the articles Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Gamboa, R., Perfecto-Avalos, Y., Gonzalez-Garcia, J. et al. In vitro analysis of postbiotic antimicrobial activity against Candida Species in a minimal synthetic model simulating the gut mycobiota in obesity. Sci Rep 14, 16760 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66806-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66806-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A Single Key for Many Doors? Unlocking the Bio-chemical Potential of Lactobacillus bulgaricus Metabolic Postbiotic

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins (2025)

-

Synthetic microbial communities as novel models to study gut microbiome–host interactions in metabolic diseases

Discover Endocrinology and Metabolism (2025)