Abstract

Although the independent effects of ambient CO, temperature or humidity on stroke have been confirmed, it is still unclear where there is an interaction between these factors and who is sensitive populations for these. The stroke hospitalization and ambient CO, temperature, humidity data were collected in 22 Counties and districts of Ningxia, China in 2014–2019. The lagged effect of ambient CO, temperature or humidity were analyze by the generalized additive model; the interaction were evaluated by the bivariate response surface model and stratified analysis with relative excessive risk (RERI). High temperature and CO levels had synergistic effects on hemorrhagic stroke (RERI = 0.05, 95% CI 0.033–0.086) and ischemic stroke (RERI = 0.035, 95% CI 0.006–0.08). Low relative humidity and CO were synergistic in hemorrhagic stroke (RERI = 0.192, 95% CI 0.184–0.205) and only in ischemic stroke in the elderly group (RERI = 0.056, 95% CI 0.025–0.085). High relative humidity and CO exhibited antagonistic effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in both male and female groups (RERI = − 0.088, 95% CI − 0.151to − 0.031; RERI = − 0.144, 95% CI − 0.216 to − 0.197). Exposure to CO increases the risk of hospitalization related to hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes. CO and temperature or humidity interact with risk of stroke hospitalization with sex and age differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Experimental and clinical studies suggest that low concentrations of exogenous carbon monoxide (CO) may have beneficial neuroprotective effects in some cases1,2,3,4,5. However, population-based epidemiological studies of environmental CO exposure yielded mixed results. In a meta-analysis that involved 6.2 million events in 28 countries hospital admissions and deaths from stroke were associated with increased CO concentrations6. However, other multi-center studies showed that stroke admissions are either not or inversely correlated with ambient CO, after adjusting the concentrations for other air pollutants like SO2 and nitrogen dioxide7,8,9,10,11. This suggests that the health effects of environmental CO on stroke are still unclear, and the effect values vary based on other pollutants present.

The independent effects of atmospheric pollutants and meteorological factors on stroke have been supported by much evidence12,13. However, the risk factors for stroke are unlikely to occur alone but in clusters. Some scholars pointed out that air pollution will accelerate climate change14, which will, in turn, also change the emission and diffusion of pollutants. Therefore, the health risks caused by the combined action of air pollutants and meteorological factors may be greater than the single role of atmospheric pollutants or meteorological factors.

CO is one of the six major air pollutants and is generally produced by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels such as motor vehicles15,16,17. Environmental factors, including temperature and humidity, can exert an impact on a car’s CO emissions. For example, in low-temperature, humid environments, the combustion efficiency of cars decreases, while the carbon monoxide emissions increase. In addition, when the car is driving at low speed in congested road conditions, the fuel combustion efficiency reduces, resulting in increased carbon monoxide emissions18,19. However, there is no clear evidence on whether temperature and humidity have a synergistic effect with environmental CO to increase the risk of stroke hospitalization in people.

In this study, we used time series analysis to examine the relationship between short-term exposure to environmental CO and the risk of stroke hospitalization. Considering that transportation is one of the major sources of carbon monoxide, we adjusted other transport-related pollutants such as PM2.5 or nitrogen dioxide. More importantly, we analyzed the effects of the interactions between temperature, humidity, and carbon monoxide on stroke hospitalizations in residents. We also performed subgroup analyses based on sex, age, and stroke subtypes to determine the subsets that are more susceptible to the effects of CO.

Materials and methods

The ethics committee of People’s Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region approved this study (Approval number: 2020-ZDYF-001). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants and/or their legal guardians have informed consent. The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study area

This study was implemented in the Ningxia, which located in northwest China and has jurisdiction over five prefecture-level cities 22 Counties and districts with a total area of 66,400 km2 and a permanent resident population of 7.25 million. The average temperature in Ningxia between 5.6 and 10.1 °C, and the annual precipitation between 167.2 and 674.3 mm.

Hospitalization data

The records of stroke were collected from the homepage of the discharge medical records of 56 hospitals in 22 Counties and districts of Ningxia. The daily hospitalization data of stroke, including admission date, age, gender, current address, and discharge diagnosis were screened from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019. Based on the incidence characteristics of stroke, the hospitalized cases of stroke were classified into either hemorrhagic (ICD-10: I60–I61) or ischemic stroke (ICD-10: I62–I63).The study excluded individuals under 18 years of age and non-local residences of residence for less than 6 months. Considering the differences in sensitivity to pollutants and meteorological factors among people of different ages and genders, the study divided hospitalized stroke cases into two subgroups, which are, adult (18–64 years old) and the elderly (≥ 65 years old), as well as two subgroups of males and females.

The ethics committee of People’s Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region approved this study (Approval number: 2020-ZDYF-001). The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.All participants and/or their legal guardians have informed consent.

Air pollution and meteorological data

Atmospheric pollution data were obtained from the National Urban Air Quality Real-Time Dissemination Platform (https://air.cnemc. cn:18007/), which is operated by the National Environmental Monitoring Center of China, in accordance with China’s Ambient Air Quality Standards (GB3095-2012). The simultaneous meteorological data were obtained from the China Meteorological Data Service Center (http://data.cma.cn/). Data on air pollutants in the Ningxia region were obtained by summarizing the data from five municipalities, as well as the arithmetic averages: the 24-h average concentration of CO (mg/m3), daily average temperature (°C), and the daily average relative humidity (%) over the patient’s region.

Generalized additive model (GAM)

A time-series approach was used to evaluate the short-term effects of CO on the risk of stroke-related hospitalization. Considering that the number of daily hospitalization cases related to stroke is a small probability event relative to the resident population in Ningxia, and the distribution type is similar to Poisson, the study used a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) with Poisson-like regression to incorporate CO into a single-pollutant model. In light of the lagged nature of the effects of CO on health, the study analyzed the one-day lagged effects on the same day of CO exposure and from days 1 to 7 (Lag1–Lag7) after exposure were analyzed. The cumulative lagged effects were also analyzed by using the moving average of the concentrations from days 1 to 7 after CO exposure (Lag01–Lag07). The study used generalized cross-validation (GCV) to control confounding factors such as time trends, temperature, and relative humidity. Day-of-the-week and vacation effects were adjusted by dummy variables in the model. The degrees of freedom of the model were estimated based on the GCV and were set to seven per year for the time trend and three for temperature and relative humidity.

The GAM formula is as follows:

In the above equation: \(Y_{t}\)—number of stroke hospitalizations on day t; \(\mu_{t}\)—expected number of stroke hospitalizations at day t; \({\upbeta }_{0}\)—intercept; \({\upbeta }_{1} {\text{X}}_{{\text{t}}} {-\!\!-}{\upbeta }_{1}\) is the regression coefficient of the effect of air pollutants on stroke hospitalization, and is the value of air pollutant concentration on day t; \({\text{ns}}\)—natural cubic spline functions controlling for confounding factors such as time trends, temperature, relative humidity, etc.; the \({\text{time}}\)—time-variant, \({\text{time}} = 1,{ }2,{ }3 \ldots 1826\); df—degree of freedom; \({\text{Z}}_{{\text{t}}}\)—meteorological factor variables on day t, including air temperature, relative humidity; \({\text{DOW}}_{{\text{t}}}\)—a dichotomous variable for the weekend effect, with weekdays as “0” and weekends as “1”;\(holiday_{t}\)—a dichotomous variable for the vacation effect, with “0” for weekdays and “1” for vacations.

Based on the regression coefficients of CO and its standard error (SE) estimated by the model, the percentage changes in the risk of stroke-related hospitalization for each unit increase in CO concentration (per increase in CO) was calculated as the excess risk (excessive risk, ER): ER = 0 indicated that the risk of morbidity was the same in both the exposed and control groups; ER < 0, which indicated that the risk of morbidity in the exposed group was lower than that in the control group; ER > 0 means that the risk of morbidity in the exposed group is higher than that in the control group.

Sensitivity analysis

Dual-pollutant model

After using the single-pollutant model for estimating the health effects of CO, a two-pollutant model was further constructed by introducing the other air pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2 and O3) separately and in a linear form. The number of lagged days that were meaningful, with the largest effect values in the one-factor analysis, were considered. Observing the change in effect values can be used to verify the stability of the model, in addition to testing whether the health-related effects of one pollutant are affected by other co-existing pollutants. The dual-pollutant model equation is as follows:

\({\upbeta }_{2} {\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}}0}}\)—\({\upbeta }_{2}\) are regression coefficients for the effect on hospitalization for hemorrhagic stroke after adjusting for air pollutants. \({\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}}0}}\) is the concentration value of another air pollutant on day t. Other variables are the same as Eq. (2).

Freedom to change

The stability of the main model that was constructed in this study was verified by changing the degrees of freedom of the time trend and other confounding factors in the single-pollutant model. The changes in the effect values were then observed after the alterations in the parameters.

Exposure-response curves

Finally, the exposure-response relationship curves between environmental CO and the risk of hospitalization in the population were plotted, based on the GAM.

Bivariate response surface model

Due to the varying nature and units of CO as well as temperature and humidity, the study used the tensor product smoothing function (Te) to build a bivariate response surface model of these parameters. The response planes of CO-temperature and humidity-health outcomes were plotted to qualitatively determine possible interaction between the two.

Tensor product smoothing function for the interaction of Te–CO with air temperature and humidity, \({\text{Pol}}_{{\text{t}}}\) is the concentration of the pollutant on day t, \({\text{Met}}_{{\text{t}}}\) denotes the value of the meteorological factor on day t.

Interaction analysis

The study used the median ambient CO concentration (P50) as the cut-off point to classify CO into low and high levels. The P5 and P95 of air temperature and humidity were used as cut-off points to categorize these parameters into low, medium, and high levels. A two-by-two combination of ambient CO concentration levels and temperature and humidity levels were performed to analyze the effects of the interaction between temperature, humidity, and ambient CO on the risk of stroke-related hospitalization. The combination of the medium levels of temperature and humidity- and the low concentration of CO was used as a reference to this effect. The direction and magnitude of the interaction were assessed using the relative excessive risk due to interaction (RERI):

R11 is the RR value when exposed to both low and high levels of temperature and humidity, as well as high levels of CO pollution. R10 and R01 are the RR values when exposed to low or high levels of temperature and humidity, as well as low levels of CO pollution. Alternatively, these might be RR values when exposed to medium levels of temperature and humidity as well as high levels of CO pollution. R00 is the RR value when exposed to medium levels of temperature and humidity as well as low levels of CO pollution, which is set to be 1. When the RERI > 0 and the 95% CI does not contain 0, a synergistic interaction exists between the two factors. When RERI < 0 and the 95% CI does not contain 0, an antagonistic interaction exists between the two factors. When RERI = 0, no interaction exists.

Statistical analysis

Excel 2019 was used to clean and organize the raw data while descriptive analysis was done using SPSS25.0. The main statistical analysis was carried out using R4.1.2 software. The “splines” package was used to call the natural cubic spline function. Both the generalized summation model and the generalized additive model were constructed using the “mgcv” package. The test level was α = 0.05, and a two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

The ethics review committee of The People’s Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region approved this study (Approval number: 2020-KY-053). The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Results

Basic information

A total of 138,851 stroke cases were included in the study, of which 121,946 (87.83%) were ischemic strokes and 16,905 (12.17%) were hemorrhagic strokes. In the age subgroup, the results were as follows: 84,528 (69.3%) ischemic strokes in young people and 17,418 (30.7%) in the elderly; 8752 (51.8%) hemorrhagic strokes in young people and 8153 (48.2%) in the elderly. In the gender subgroup, the findings for ischemic stroke showed that there were 63,698 (52.2%) and 58,248 (47.8%) in males and females, respectively. In the gender subgroup, there were 10,244 (60.6%) male and 6661 (39.4%) female cases of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke.

During the study period, the average daily concentration of CO in Ningxia was 0.87 mg/m3, which was lower than the limit of the secondary standard in the Ambient Air Quality Standard (GB 3095-2012). The average temperature in spring is 12.42 °C, the average temperature in summer is 22.91 °C, the average temperature in autumn is 10.52 °C, and the average temperature in winter is − 3.68 °C. The average relative humidity in spring was 38.33%, 54.16% in summer, 58.47% in autumn and 45.37% in winter. As shown in the time series plot (Fig. 1), the CO concentration was relatively higher in winter and spring, and it reduced in summer and fall. Apparently, the average daily temperatures and relative humidity showed a cyclical trend, with the former being higher in summer than in winter and the latter being higher in summer and fall, compared to the winter and spring.

Lagged effect of CO on the risk of stroke hospitalization

The lagged effect of CO on the risk of hospitalization for hemorrhagic stroke is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The single-day lagged and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization for the total population of hemorrhagic stroke were found at Lag0 (ER = 1.394, 95% CI 0.573–2.221), and Lag05 (ER = 1.945, 95% CI 0.432–3.480), respectively. The largest effect value was observed. In the age subgroups, the single-day lagged effect of CO on hospitalization in the young and middle-aged group with hemorrhagic stroke was at Lag0 (ER = 1.197, 95% CI 0.136–2.268) on the day of exposure. The single-day lagged and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the elderly group with hemorrhagic stroke were at Lag0 (ER = 1.625, 95% CI 0.436–2.829) and Lag05 (ER = 2.646, 95% CI 0.448–4.893), respectively, with the largest effect values being noted. For the gender subgroups, the one-day lagged effect of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the male participants with hemorrhagic stroke was found at Lag0 (ER = 1.987, 95% CI 0.954–3.030), while the cumulative lagged effect was at Lag04 (ER = 2.220, 95% CI 0.453–4.019), with the largest effect values being noted. The effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the female group of participants with hemorrhagic stroke were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

The results for the lagged effect of CO on the risk of hospitalization for ischemic stroke are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The single-day and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization for the whole ischemic stroke population were at Lag1 (ER = 0.837, 95% CI 0.116–1.563) and Lag04 (ER = 1.889, 95% CI 0.712–3.081), respectively, with the effect values being the largest. In the age subgroups, the largest effect values for the single-day and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the young and middle-aged group of participants with ischemic stroke were found at Lag3 (ER = 0.809, 95% CI 0.085–1.538) and Lag03 (ER = 1.841, 95% CI 0.7001–2.994), respectively. The single-day lagged and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the old and middle-aged groups of ischemic stroke were the largest at Lag3 (ER = 0.891, 95% CI 0.7001–2.994). Apparently, the single-day and cumulative lagged effects were largest at Lag1 (ER = 0.982, 95% CI 0.145–1.826) and Lag04 (ER = 2.083, 95% CI 0.713–3.471), respectively. In the gender subgroup, no statistical significance (P > 0.05) was noted for the single-day lagged effect of CO on the risk of hospitalization in the male participants with ischemic stroke. However, the cumulative lagged effect had the largest effect value at Lag04 (ER = 1.68, 95% CI 0.436–2.939). In the female group of ischemic stroke, the one-day and cumulative lagged effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization were statistically significant at Lag0 (ER = 1.011, 95% CI 0.244–1.784) and Lag03 (ER = 2.166, 95% CI 0.96–3.387), where the effect values were the largest.

Sensitivity analysis

Based on the number of lag days with the strongest pollutant effects, sensitivity analyses were done by both constructing a two-pollutant model and changing the degrees of freedom in a bid to judge the stability of the model. In the two-pollutant model, the other pollutants were analyzed separately by including them in the GAM in a linear form (Table 2). The results of the two-pollutant model remained essentially stable, except for a statistically insignificant number of days of lag between CO and the risk of stroke hospitalization, after adjusting for NO2 and PM2.5.

Compared with the results of the main model, changing the degrees of freedom of 6, 7, 9, and 10 for the time trend in the model, as well as 4 and 5 for temperature, relative humidity, and barometric pressure, respectively, did not affect the effect values.

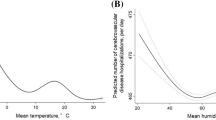

The exposure-response relationship curves between ambient CO and residential stroke hospitalization risk (Fig. 3) show that there is a curvilinear positive trend between the two parameters when other pollutants are being controlled. The results indicate that the association between ambient CO and residential hospitalization risk obtained from the main model is stable and robust.

Exposure–response curves for the relationship between environmental CO and the risk of hospitalization for stroke in the population. (Figure labels A is the exposure-response relationship curve between CO and the number of hospitalizations for hemorrhagic stroke. Figure labels B is the exposure-response relationship curve between CO and the number of hospitalizations for ischemic stroke.)

Interaction of CO and temperature on risk of stroke hospitalization

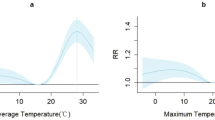

As shown in Fig. 4A and Table 3, high temperature and ambient CO had synergistic effects on the risk of hospitalization in the total population for hemorrhagic stroke (RERI = 0.05, 95% CI 0.033–0.086). Based on subgroup analyses, high temperature and CO had significant effects on the risk of hospitalization in the male group (RERI = 0.038, 95% CI 0.02–0.087), female group (RERI = 0.067, 95% CI 0.045–0.134), young and middle-aged group (RERI = 0.042, 95% CI 0.023–0.095), and elderly group (RERI = 0.058, 95% CI 0.038–0.117). Apparently, hypothermia and CO had no interaction with hemorrhagic stroke.

The results of the bivariate response surface model (Fig. 4B) showed that the effects of ambient CO on ischemic stroke hospitalization increased with rising temperatures. Notably, the number of ischemic stroke hospitalizations peaked when both temperatures and CO levels were high. Synergistic effects of high temperature and CO on the risk of hospitalization in the total ischemic stroke population (RERI = 0.035, 95% CI 0.006–0.08) were noted. Subgroup analyses revealed synergistic effects of high temperature and CO on the risk of hospitalization in the young and middle-aged group (RERI = 0.059, 95% CI 0.027–0.111), and the male group (RERI = 0.076, 95% CI 0.042–0.128). Additionally, hypothermia and CO had antagonistic effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in the elderly group (RERI = − 0.143, 95% CI − 0.25 to − 0.051) and in the male group (RERI = − 0.1, 95% CI − 0.192 to − 0.017). It’s important to note that high temperature, hypothermia, and CO had no interaction effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in the female group.

Interaction of CO and relative humidity on the risk of stroke hospitalization

As shown in Fig. 5A and Table 3, low relative humidity and ambient CO had synergistic effects on the risk of hospitalization for the total population with hemorrhagic stroke (RERI = 0.192, 95% CI 0.184–0.205). Results from the subgroup analyses showed that low relative humidity and CO had synergistic effects on the risk of hospitalization for the male group (RERI = 0.175, the 95% CI 0.163–0.194), female group (RERI = 0.22, 95% CI 0.216–0.234), young and middle-aged group (RERI = 0.196, 95% CI 0.185–0.214), and elderly group (RERI = 0.1877, 95% CI 0.178–0.205). There was no interaction between high relative humidity and CO as far as the risk of hemorrhagic stroke hospitalization in any of the different subgroups was concerned.

As shown in Fig. 5B and Table 3, Low relative humidity did not interact with CO to affect the risk of hospitalization in the total population of ischemic stroke. On the other hand, high relative humidity and CO had antagonistic effects on the risk of hospitalization in the total population of ischemic stroke (RERI = − 0.115, 95% CI − 0.176 to − 0.058). In the age subgroup, low relative humidity and CO had synergistic effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in the elderly group (RERI = 0.056, 95% CI 0.025–0.085) while high relative humidity and CO had antagonistic effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in the young group (RERI = − 0.147, 95% CI − 0.214 to − 0.084). In the sex subgroup, high relative humidity and CO exhibited antagonistic effects on the risk of ischemic stroke hospitalization in both male and female groups (RERI = − 0.088, 95% CI − 0.151 to − 0.031; RERI = − 0.144, 95% CI − 0.216 to − 0.197. Low relative humidity did not have any notable interactions.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that there is a positive association between environmental CO and the risk of stroke hospitalization in the studied population. It was also noted that for hemorrhagic stroke, men and residents who were older than 65 years of age may be more sensitive to environmental CO, while there were no significant differences by age group with regard to ischemic stroke. In the gender group, women were more sensitive to environmental CO. Studies at home and abroad have shown that there is a positive association between stroke hospitalization and CO20,21, which is consistent with the results of this paper. A possible mechanism is that exposure to carbon monoxide impairs mitochondrial function in organisms, thereby generating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, as well as releasing pro-inflammatory mediators and pro-apoptotic mediators. CO also modulates signaling pathways, thereby affecting key biological processes, including autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, programmed cell death (apoptosis), cell proliferation, as well as inflammation and innate immune response22. This, in turn, induces a number of cardiovascular diseases that lead to stroke.

Previous studies23 have shown that temperature is a major factor affecting the concentration of air pollutants.CO and high temperatures have synergistic effects on the risk of hospitalization for stroke. Previous systematic reviews and time-series studies have yielded similar results24,25. This may be due to the fact that sustained high temperatures promote photochemical reactions in the atmosphere, leading to an increase in the production of atmospheric pollutants such as CO. In addition, there is a common biological mechanism for the effects of temperature and atmospheric pollutants on population health, whereby extreme temperatures exacerbate inflammatory responses and trigger damage to the endothelium of the blood vessels, resulting in increased cholesterol levels and blood viscosity, as well as altered coagulation function. This ultimately leads to a range of human health effects26,27.

Changes in temperature are often accompanied by changes in humidity, and studies have shown that high and low relative humidity may be associated with the risk of stroke hospitalization28, this study found that high humidity has an antagonistic effect with CO, low humidity has a synergistic effect with CO, and higher humidity may help reduce pollutants in the air, including CO, because water vapor may promote the sedimentation of some pollutants. In addition, a high humidity environment may help maintain the body’s water balance and reduce the risk of dehydration, which may have a protective effect on the cardiovascular system. In a high humidity environment, the increased effect of CO on stroke risk may be offset or diminished by the potential benefits of humidity itself. Low relative humidity may mean less moisture in the air, which may exacerbate the dryness of the respiratory tract, which affects the respiratory system’s defense mechanisms. At the same time, carbon monoxide, as a colorless and odorless toxic gas, can spread and accumulate in the air more easily in low humidity environments, increasing the risk of human inhalation. In addition, Ningxia is located in the northwest of the province with a dry climate, and when the summer is hot, it will be accompanied by low relative humidity, so there is a synergistic effect between high temperature and low humidity and CO on the risk of stroke hospitalization.

The results from the subgroup analyses indicated that the effects of CO on the risk of hospitalization for stroke in the population were more sensitive among male than female, as it was among the elderly than the young and middle-aged, which is consistent with the findings of Liu et al.21. In addition, a recent study on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in China reported that male adults were associated with a relatively high prevalence of smoking, alcohol consumption, hypertension, and diabetes, which may make them more susceptible to the effects of air pollution. The stronger association of older adults with air pollution may be related to a gradual decrease in physiologic processes20,29,30,31,32, reduced clearance of air pollutants from the airways, and a higher prevalence of preexisting cardiovascular and respiratory diseases33. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the elderly due to their higher risk of exposure to air pollution.

This study had some limitations. First, we used the average of meteorological and air pollution data from five urban areas as an indicator of residential exposure, not taking into account the differences in CO concentrations, temperatures, and relative humidity in different areas. This could lead to misclassification of exposures and a potential bias in the study results. Second, the limited availability of data made it difficult to control more detailed meteorological variables (e.g. wind speed and barometric pressure), demographic information (e.g. education level and socioeconomic status), and other relevant behavioral risk factors (e.g. smoking status, physical activity, and dietary habits). In addition, we obtained the dates of hospitalization for stroke rather than the onset dates, which in some stroke patients may have been a few days prior to admission. Furthermore, we did not consider cases where death occurred prior to admission, and such uncertainties may have led to information bias in the exposure assessment. However, stroke is an acute disease with severe symptoms, and in China, most stroke patients are likely to visit the nearest hospital within six hours after the onset of symptoms34, so misclassification bias may be limited. Finally, the data were collected in one province in northwest China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings from this study. Therefore, further large-scale studies in developing countries are encouraged to validate the findings from the current study in different populations.

Conclusion

Short-term exposure to CO increases the risk of hospitalization for both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in the population. The interactions between CO and meteorological factors had effects on the risk of hospitalization for stroke. The effects tend to vary with age and gender differences. Therefore, care should be taken to protect susceptible populations under specific climatic conditions to reduce their risk of being affected by hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yabluchanskiy, A. et al. CORM-3, a carbon monoxide-releasing molecule, alters the inflammatory response and reduces brain damage in a rat model of hemorrhagic stroke. Crit. Care Med. 40, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822f0d64 (2012).

Bauer, M., Witte, O. W. & Heinemann, S. H. Carbon monoxide and outcome of stroke—A dream CORM true?. Crit. Care Med. 40, 687–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232d31a (2012).

Motterlini, R. & Otterbein, L. E. The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 728–743. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3228 (2010).

Hanafy, K. A., Oh, J. & Otterbein, L. E. Carbon Monoxide and the brain: Time to rethink the dogma. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 2771–2775. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612811319150013 (2013).

Wang, B., Cao, W., Biswal, S. & Doré, S. Carbon monoxide-activated Nrf2 pathway leads to protection against permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 42, 2605–2610. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.607101 (2011).

Shah, A. S. et al. Short term exposure to air pollution and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 350, h1295. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1295 (2015).

Lim, S. S. et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2224–2260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8 (2012).

Milojevic, A. et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on a range of cardiovascular events in England and Wales: Case-crossover analysis of the MINAP database, hospital admissions and mortality. Heart 100, 1093–1098. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304963 (2014).

Liu, C. et al. Ambient carbon monoxide and cardiovascular mortality: A nationwide time-series analysis in 272 cities in China. Lancet Planet Health 2, e12–e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(17)30181-x (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Association between ambient air pollution and hospitalization for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in China: A multicity case-crossover study. Environ. Pollut. 230, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.057 (2017).

Tian, L. et al. Carbon monoxide and stroke: A time series study of ambient air pollution and emergency hospitalizations. Int. J. Cardiol. 201, 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.099 (2015).

Verhoeven, J. I., Allach, Y., Vaartjes, I. C. H., Klijn, C. J. M. & de Leeuw, F. E. Ambient air pollution and the risk of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Lancet Planet Health 5, e542–e552. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00145-5 (2021).

Fisher, J. A. et al. Case-crossover analysis of short-term particulate matter exposures and stroke in the health professionals follow-up study. Environ. Int. 124, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.044 (2019).

Zanobetti, A. & Peters, A. Disentangling interactions between atmospheric pollution and weather. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 69, 613–615. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-203939 (2015).

Chen, R. et al. Ambient carbon monoxide and daily mortality in three Chinese cities: The China air pollution and health effects study (CAPES). Sci. Total Environ. 409, 4923–4928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.029 (2011).

Duci, A., Chaloulakou, A. & Spyrellis, N. Exposure to carbon monoxide in the Athens urban area during commuting. Sci. Total. Environ. 309, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-9697(03)00045-7 (2003).

Cox, B. D. & Whichelow, M. J. Carbon monoxide levels in the breath of smokers and nonsmokers: Effect of domestic heating systems. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 39, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.39.1.75 (1985).

Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A. & Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: A review. Front. Public Health 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014 (2020).

Han, X. & Naeher, L. P. A review of traffic-related air pollution exposure assessment studies in the developing world. Environ. Int. 32, 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2005.05.020 (2006).

Tian, Y. et al. Association between ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for ischemic stroke: A nationwide time-series analysis. PLoS Med. 15, e1002668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002668 (2018).

Liu, T. et al. Joint associations of short-term exposure to ambient air pollutants with hospital admission of ischemic stroke. Epidemiology 34, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000001581 (2023).

Ryter, S. W., Ma, K. C. & Choi, A. M. K. Carbon monoxide in lung cell physiology and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 314, C211-c227. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00022.2017 (2018).

Huang, J. & Yang, Z. Correlation between air temperature, air pollutants, and the incidence of coronary heart disease in Liaoning Province, China: A retrospective, observational analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10, 12412–12419. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-3212 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Interactions between ambient air pollutants and temperature on emergency department visits: Analysis of varying-coefficient model in Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ. 668, 825–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.049 (2019).

Lin, C. M. & Liao, C. M. Temperature-dependent association between mortality rate and carbon monoxide level in a subtropical city: Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 19, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603120802460384 (2009).

Schneider, A. et al. Air temperature and inflammatory responses in myocardial infarction survivors. Epidemiology 19, 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a4325 (2008).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: A multicountry observational study. Lancet 386, 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62114-0 (2015).

Guo, Y., Luo, C., Cao, F., Liu, J. & Yan, J. Short-term environmental triggers of hemorrhagic stroke. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 265, 115508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115508 (2023).

Ekström, I. A., Rizzuto, D., Grande, G., Bellander, T. & Laukka, E. J. Environmental air pollution and olfactory decline in aging. Environ. Health Perspect. 130, 27005. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp9563 (2022).

de Bont, J. et al. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular diseases: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Intern. Med. 291, 779–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13467 (2022).

Gao, X., Huang, N., Guo, X. & Huang, T. Role of sleep quality in the acceleration of biological aging and its potential for preventive interaction on air pollution insults: Findings from the UK Biobank cohort. Aging Cell 21, e13610. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13610 (2022).

Danesh Yazdi, M. et al. The effect of long-term exposure to air pollution and seasonal temperature on hospital admissions with cardiovascular and respiratory disease in the United States: A difference-in-differences analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 156855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156855 (2022).

Sacks, J. D. et al. Particulate matter-induced health effects: Who is susceptible?. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002255 (2011).

Fang, J., Yan, W., Jiang, G. X., Li, W. & Cheng, Q. Time interval between stroke onset and hospital arrival in acute ischemic stroke patients in Shanghai, China. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 113, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.09.004 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (https://www.editsprings.cn) for the expert linguistic services provided.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key R&D Project of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (Grant Number 2021BEG03099) and the Ningxia Natural Science Foundation (Grant Number 2023AAC03445).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PL had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and responsible for concept and design. ZL and HM drafted the manuscript. PL critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. ZL carried out the statistical analysis and HM supervised the research. All authors were involved in data acquisition, cleaning, analysis, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version. These authors contributed equally: Zhuo Liu and Hua Meng.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Meng, H., Wang, X. et al. Interaction between ambient CO and temperature or relative humidity on the risk of stroke hospitalization. Sci Rep 14, 16740 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67568-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67568-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Short-term exposure to PM2.5 constituents and daily ischemic stroke hospitalization in the arid, semi-arid and semi-humid regions of northwest China

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2025)