Abstract

The relationship between tinnitus and body composition in specific regions has not been extensively investigated. This study aimed to identify associations between tinnitus and body composition. Individuals with data on physical and otological examination findings, and bioelectrical impedance analysis were included from the ninth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. They were divided into a tinnitus group and a non-tinnitus group. Participants with tinnitus were further classified into acute or chronic tinnitus group. The tinnitus group showed significantly higher body fat percentages in each region (arms: P = 0.014; legs: P = 0.029; trunk: P = 0.008; whole body: P = 0.010) and waist circumference (P = 0.007) than the non-tinnitus group, and exhibited lower leg muscle percentage (P = 0.038), total body fluid percentage (P = 0.010), and intracellular fluid percentage (P = 0.009) than the non-tinnitus group in men. Furthermore, men with chronic tinnitus showed a significantly higher trunk fat percentage (P = 0.015) and waist circumference (P = 0.043), and lower intracellular fluid percentage (P = 0.042) than their counterparts without tinnitus. No significant differences in body composition were observed among the groups in the female population. In men, body composition may be associated with tinnitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tinnitus is an auditory perception that can be bothersome to patients1. It is categorized into two types: subjective tinnitus, which only the affected individuals can perceive, and objective tinnitus, which can be detected by physicians or others1. While objective tinnitus often stems from mechanical issues of vascular or muscular origins, many subjective tinnitus cases are attributed to hearing loss1. Nevertheless, subjective tinnitus also occurs in individuals with normal hearing. In such cases, research has found correlations between tinnitus and various physical conditions, including pain, infection, and sleep quality, as well as mental health issues like anxiety and depression1,2. Furthermore, subjective tinnitus has a significant relationship with brain metabolism and structure3. Therefore, some diseases that cause changes in the brain network through chronic inflammatory responses or are associated with structural and functional changes in the brain might be connected to subjective tinnitus4,5.

Some authors have also identified an association between tinnitus and obesity2. Özbey-Yücel and Uçar reviewed several articles and suggested that this relationship may be due to an elevated inflammatory response in obese patients2. Michaelides et al. found that pulsatile tinnitus is also linked to obesity and that weight reduction can be an effective treatment for this condition6. Furthermore, McCormack et al. determined that both body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage were significantly associated with tinnitus7. However, they did not evaluate the type of obesity or the distribution of fat in obese patients.

Obesity is categorized into subtypes based on the distribution of body fat, with each subtype associated with distinct health conditions and disease characteristics8,9. The gold standard for evaluating body fat distribution is an imaging workup such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging10. However, due to considerations of time and cost, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry is commonly recommended for evaluating body composition, and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) has also demonstrated high precision in this regard10,11. In this study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between body composition, as assessed by BIA, and tinnitus, as well as the chronicity of tinnitus in individuals with age-normative hearing levels. We specifically excluded individuals with hearing loss, which is known to be associated with tinnitus, from this study1. We also considered other factors that are linked to both tinnitus and obesity in order to identify the specific body composition patterns that are associated with tinnitus.

Materials and methods

Data source

We used data from the ninth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (KNHANES). Data were extracted on age; sex; household income (quintile); weight; height; BMI; waist circumference; the body fat, muscle, and fluid percentage of each region; hypertension; diabetes; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)12; Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)13; history of dizziness; tinnitus; air-conduction hearing thresholds at 0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 8 kHz; and tympanic membrane status evaluated by tympanometry. The three individuals who selected “I don't remember” regarding their history of dizziness were classified as having no such history. Body composition measurements, including body fat, muscle, and fluid percentages, were conducted using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) with the Inbody 970 device (Inbody, Seoul, Korea). We calculated the regional percentages of body fat, muscle, and fluid relative to total body mass by dividing the mass of each component in a given region by the total body weight. For the arms and legs, we determined the percentages of each composition by averaging the values from both the right and left sides. The PHQ-9 is a valid tool for evaluating depressive mood12, while the GAD-7 is a developed survey used for evaluating anxiety13. Air-conduction pure tone audiometry was carried out in a double-walled soundproof booth using an AD629 audiometer (Interacoustics, Assens, Denmark). Tympanometry was performed with a Titan IMP440 screener (Interacoustics, Assens, Denmark). Audiological assessments were conducted only on individuals aged 40 and above in the 9th KNHANES, a decision likely influenced by the increased prevalence of hearing loss in this age group14. All participants in the ninth KNHANES gave informed consent for this survey, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) before the survey was conducted (IRB No. 2018-01-03-4C-A). The 9th KNHANES was conducted according to the examination guidelines provided by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Additionally, this study adhered to the STROBE guidelines.

Data availability

The ninth KNHANES data, which was used in our study, can be accessed through “https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_05.do”.

Definition of normal hearing considering the age-norm hearing level

Since elderly individuals typically have higher hearing thresholds than young adults, with mean hearing thresholds—calculated by averaging frequencies at 0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, and 4 kHz—being approximately 30 dB in their 70 s and around 40 dB in those over 80 years of age15, we used a 40 dB mean hearing threshold as the cutoff for hearing loss in our inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of study subjects

From the participants in the ninth KNHANES, we selected subjects according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Individuals with data on age; sex; household income (quintile); weight; height; BMI; waist circumference; the body fat, muscle, and fluid percentage of each region; hypertension; diabetes; PHQ-9; GAD-7; history of dizziness; tinnitus; air-conduction hearing thresholds at 0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 8 kHz; and tympanic membrane status evaluated by tympanometry

Exclusion criteria

-

Individuals who had mean hearing thresholds more than 40 dB

-

Individuals with type B and C results from tympanometry, which represent abnormal tympanic membranes, such as a tympanic membrane perforation, otitis media, or a retracted tympanic membrane.

Definition of tinnitus and subject classification

In the ninth KNHANES, tinnitus was assessed through a survey and defined as present when a participant reported the symptom lasting for five minutes or more within the past year. Acute tinnitus was further defined as lasting for five minutes or more but less than 6 months, while chronic tinnitus was defined as having a duration of 6 months or more.

The study subjects were classified into two groups—the tinnitus group and the non-tinnitus group—based on the presence or absence of tinnitus. Those with tinnitus were also categorized into chronic and acute subgroups according to the chronicity of the condition.

Definition of obesity and central obesity

Obesity was defined according to the guidelines provided by the World Health Organization, using total body fat percentage with a cutoff of 25% for males and 35% for females16. Central obesity was diagnosed based on the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity guidelines, using waist circumference with a threshold of 90 cm or over for males and 85 cm or over for females17.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance and the chi-square test were conducted to compare the variables among the groups. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to compare the categorical variables among the groups after adjusting other factors. Multivariate analysis of covariance was performed for significant variables identified in the univariable study to control for other covariates and adjusted mean value of body composition in each part of the body. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The symbols *, **, and *** were used for P-values less than 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively, in the figures.

Results

Demographic factors, economic status, underlying diseases, and audiological characteristics of each group

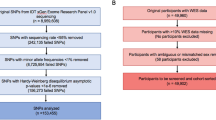

Among the 6265 KNHANES participants who were initially considered, 3377 were screened out due to lack of data. Subsequently, 256 individuals with abnormal tympanic membranes were excluded. To control for the effect of hearing loss, we excluded 375 individuals who had a hearing threshold higher than 40 dB in the better ear. Ultimately, 2257 individuals were included in this study (Fig. 1). Of these, 204 were classified into the tinnitus group, and 2125 were classified into the non-tinnitus group.

Inclusion process of subjects in this study from ninth Korea National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey. KNHANES Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, N number, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 generalized anxiety disorder-7; BIA bioelectrical impedance analysis, AC air-conduction, PTA pure tone audiometry.

The mean age of the tinnitus group (60.22 ± 11.30 years) was older than that of the non-tinnitus group (57.09 ± 10.68 years, P < 0.001). Tinnitus prevalence was higher among men (11.76%) than among women (6.90%, P < 0.001). The mean household income was significantly lower in the tinnitus group (quintile mean = 2.91 ± 1.31) than in the non-tinnitus group (quintile mean = 3.34 ± 1.36, P < 0.001). Hypertension was more prevalent in the tinnitus group (36.68%) than in the non-tinnitus group (29.30%, P = 0.030). However, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of diabetes between the groups (P = 0.215). The tinnitus group showed higher PHQ-9 (3.00 ± 4.42) and GAD-7 scores (2.57 ± 4.02) than the non-tinnitus group (PHQ-9: 2.10 ± 3.28, P < 0.001; GAD-7: 1.92 ± 3.22, P < 0.001). The history of dizziness was higher in the tinnitus group (50.25%) than in the non-tinnitus group (33.33%, P < 0.001). The mean hearing level was worse in the tinnitus group (21.66 ± 9.44 dB) than in the non-tinnitus group (16.81 ± 8.52 dB, P < 0.031) (Table 1).

After controlling for age, there was a significant difference only in mean hearing level (P < 0.001) between the groups in male population (Table 2). Household income (P = 0.108), hypertension (P = 0.080), and diabetes (P = 0.497), PHQ-9 score (P = 0.053), and GAD-7 score (P = 0.083) were not significantly different between the groups in the male population. And, household income (P = 0.002), PHQ-9 score (P = 0.002), GAD-7 score (P < 0.001), history of dizziness (P < 0.001), and mean hearing level (P = 0.004) were significantly different among the groups in the female population, while other variables such as hypertension and diabetes did not show significant differences (Table 2).

Comparison of body fat, muscle, and fluid percentage of each region between the groups.

Since the distribution and amount of fat, muscle, and fluid significantly differ according to sex18, we analyzed their sex-specific associations with tinnitus.

Men

Men with tinnitus exhibited a higher percentage of body fat in each region (P = 0.005 for the total body; P = 0.007 for the arms; P = 0.006 for the trunk; P = 0.011 for the legs), a higher waist circumference (P = 0.011), and less muscle mass in each region (P = 0.024 for the arms, P = 0.010 for the legs). Additionally, they had lower total body and intracellular fluid levels (P = 0.007 for total body fluid; P = 0.002 for total intracellular fluid) (Table 3).

Women

Female participants exhibited a marginal difference in leg muscle percentage between the groups (P = 0.050), but no other differences were observed in terms of fat, muscle, and fluid percentages in various body regions (Table 3).

Multivariable analysis of fat and muscle distribution

We conducted a multivariable analysis using body composition variables that were significantly different in each region according to univariable analysis. Other variables that differed significantly between the groups were included as covariates (Table 2). After adjusting for age and mean hearing level, the tinnitus group exhibited higher total body fat percentage (P = 0.010), arm fat percentage (P = 0.014), leg fat percentage (P = 0.029), and trunk fat percentage (P = 0.008). In addition, the tinnitus group had lower leg muscle percentage (P = 0.038), body fluid percentage (P = 0.010), and intracellular fluid percentage (P = 0.009) compared to the non-tinnitus group in the male population (Fig. 2). Furthermore, waist circumference was significantly greater in the tinnitus group (mean waist circumference = 91.42 ± 0.88 cm; 95% CI 89.69–93.15 cm) than in the non-tinnitus group (mean waist circumference = 88.90 ± 0.32 cm; 95% CI 88.28–89.52 cm, P = 0.007).

Comparison of age- and mean hearing level-adjusted fat and fluid percentages in the whole body (A) and each region (B) between the tinnitus and non-tinnitus groups in the male population. * Statistically significant difference between the tinnitus group and the non-tinnitus group; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The female population did not exhibit any differences in leg muscle percentage after adjusting for other factors (P = 0.552).

Subgroup analysis for chronic tinnitus and acute tinnitus

We categorized the tinnitus cohort into two groups: those with chronic tinnitus and those with acute tinnitus, based on the duration of their symptoms.

Demographic factors

Among the tinnitus group, 152 were classified into the chronic tinnitus group and 47 were classified into the acute tinnitus group. The mean age of the chronic acute group (60.78 ± 11.01 years) was older than that of the other groups, followed by the acute tinnitus group (58.43 ± 12.12 years), and then the non-tinnitus group (57.09 ± 10.68 years, P < 0.001). The gender distribution of each group was different (chronic tinnitus M:F = 86:66; acute tinnitus M:F = 19:28; non-tinnitus M:F = 788:1270, P < 0.001).

Men

The chronic tinnitus, acute tinnitus, and non-tinnitus groups showed statistically significant differences only in hearing thresholds (P < 0.001) and exhibited no differences in household income, diabetes, hypertension, PHQ-9 score, GAD-7 score, and history of dizziness after controlling for age in the male population (Table 4).

The body fat percentage in various regions was compared among the chronic tinnitus group, the acute tinnitus group, and the non-tinnitus group within the male population. Significant differences were observed in the total body fat percentage (P = 0.019), arm fat percentage (P = 0.026), leg fat percentage (P = 0.039) and trunk fat percentage (P = 0.024) among the groups (Table 5). Furthermore, there were significant differences in leg muscle percentage (P = 0.036), total body fluid (P = 0.025), and intracellular fluid percentage (P = 0.007) across the groups (Table 5). Additionally, significant differences were found in the mean waist circumference (P = 0.040) among these groups (Table 5).

After controlling for age and mean hearing level, significant differences were observed among the groups in the male population for total body fat percentage (P = 0.035), arm fat percentage (P = 0.049), trunk fat percentage (P = 0.030), waist circumference (P = 0.028), body fluid percentage (P = 0.036), and intracellular fluid percentage (P = 0.032) (Fig. 3). In the post-hoc analysis, the chronic tinnitus group showed significantly higher trunk fat percentage (mean = 13.86 ± 0.35%; 95% CI 13.17–14.55%) and waist circumference (mean = 91.41 ± 0.97 cm; 95% CI 89.51–93.32 cm), and significantly lower intracellular fluid (mean = 33.64 ± 0.27 cm; 95% CI 33.10–34.18) than the non-tinnitus group (mean trunk fat percentage = 12.96 ± 0.11%; 95% CI 12.73–13.18%, P = 0.015; mean waist circumference = 88.90 ± 0.32 cm; 95% CI 88.28–89.52 cm, P = 0.043; mean intracellular fluid percentage = 34.35 ± 0.09%; 95% CI 34.18–34.53% , P = 0.042) in the male population.

Comparison of age- and mean hearing level -adjusted fat and fluid percentages in the whole body (A) and each region (B) among the chronic tinnitus, acute tinnitus, and non-tinnitus groups in the male population. *Statistically meaningful difference between the chronic tinnitus group and the non-tinnitus group; *P < 0.05.

Women

In the female population, significant differences were observed between the chronic and acute tinnitus groups in terms of household income (P = 0.008), PHQ-9 score (P < 0.001), GAD-7 score (P = 0.004) history of dizziness (P < 0.001), and mean hearing thresholds (P = 0.001) after adjusting for age (Table 4).

Leg muscle percentage (P = 0.043) was the only body composition-related variable that showed a significant difference between the chronic and acute tinnitus groups in the female population (Table 5). However, this relationship was no longer statistically significant after controlling for age, household income, PHQ-9 score, GAD-7 score, history of dizziness, and mean hearing threshold (P = 0.600).

Prevalence and chronicity of tinnitus in obesity or central obesity

Prevalence of tinnitus

Since we demonstrated that body fat percentage and waist circumference were significantly associated with tinnitus, we classified obesity using a cut-off of 25% body fat for males and 35% body fat for females. Central obesity was defined with a cut-off of 90 cm waist circumference for males and 80 cm for females.

Among the subjects, 46.92% and 40.47% were classified as obese in the male and female populations, respectively. The prevalence of tinnitus was much higher in males with obesity (19.03%) than in those without obesity (8.72%, odds ratio (OR) = 2.18, P < 0.001). In females, there were no differences in tinnitus prevalence between obese and non-obese patients (P = 0.280).

Additionally, 46.25% of the male population and 33.50% of the female population had central obesity. Males with central obesity showed a higher prevalence of tinnitus (16.67%) compared to those without central obesity (10.60%, OR 1.57, P = 0.030). In contrast, females did not show different prevalence rates according to their obesity status (P = 0.212).

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed for obesity and central obesity, including age and mean hearing level for males. Tinnitus was significantly associated with both obesity (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.093, 95% CI 1.357–3.227, P = 0.001) and central obesity (aOR 1.707, 95% CI 1.115–2.613, P = 0.014).

Proportion of chronic or acute tinnitus

The same evaluation was performed for chronic and acute tinnitus. The chronic tinnitus, acute tinnitus, and non-tinnitus groups occupied 13.13%, 2.86%, and 84.00%, respectively, in males with obesity, which was different from the proportions in non-obese patients (chronic tinnitus: 6.54%; acute tinnitus: 1.48%; non-tinnitus: 91.98%, P = 0.001). Additionally, males with central obesity also showed significantly different proportions of chronic, acute, and non-tinnitus groups (chronic tinnitus: 12.35%; acute tinnitus: 1.94%; non-tinnitus: 85.71%) compared to those without central obesity (chronic tinnitus: 7.29%; acute tinnitus: 2.29%; non-tinnitus: 90.42%, P = 0.037). In contrast, female individuals with obesity or central obesity did not show a difference in the proportion of chronic tinnitus or acute tinnitus compared to those without obesity (P = 0.280) or central obesity (P = 0.215).

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed including age, mean hearing level, and obesity or central obesity in the male population. The chronic tinnitus group was significantly associated with obesity (aOR 1.927, 95% CI 1.207–3.077, P = 0.006) or central obesity (aOR 2.115, 95% CI 1.318–3.393, P = 0.002).

Discussion

Previous studies have reported an association between obesity and tinnitus. However, the relationships between tinnitus and specific types of obesity or the amount of fat in each body region have not been thoroughly investigated. In our study, we demonstrated that body fat percentage, sarcopenia in the lower limbs, body fluid percentage, and intracellular water percentage are significantly associated with tinnitus, particularly in male individuals. Additionally, chronic tinnitus was found to be significantly associated with trunk fat percentage and waist circumference. It also significantly associated with obesity and central obesity.

Obesity is strongly associated with an increased risk of adult diseases, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and insulin resistance, as well as type 2 diabetes19. It also promotes systemic inflammation, which can lead to various types of systemic damage19. Furthermore, fat accumulated around the trunk is indicative of visceral fat, which is considered the most problematic site of fat accumulation20,21. Vogel et al. showed that abdominal fat is more closely associated with oxygen tension, which correlates with pro-inflammatory gene expression21. This reaction may increase cardiovascular risk in individuals with central obesity8,9. Since tinnitus is significantly related to systemic inflammation5, it is possible that tinnitus could be a side effect of upper body obesity. Moreover, considering the clinical importance of visceral fat, the chronicity of tinnitus may be more influenced by visceral obesity, as assessed by the percentage of trunk fat and waist circumference.

In addition, the metabolism and structure of brain regions associated with tinnitus are affected by obesity22,23. Previous studies have shown that patients with obesity have reduced total brain and gray matter volume, which is attributed to neuroinflammation. Furthermore, the fronto-temporal regions, which are involved in the noise cancellation pathway, are also associated with obesity3,22,23. Since tinnitus is linked to the noise cancellation pathway3, these structural changes in the brain may contribute to the onset and persistence of tinnitus.

A study revealed that obesity-related brain changes differ between sexes, with significant reductions in gray matter volume observed in the thalamus, caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens exclusively in male patients with obesity24. These areas are closely associated with tinnitus and are involved in the noise-cancellation pathway25,26. Therefore, early detection of obesity-related tinnitus can be beneficial in preventing further brain changes that may contribute to the chronicity of tinnitus. Further research is needed to identify the specific brain regions associated with tinnitus in obese individuals and to understand the mechanisms underlying their relationship.

Our results also indicated a significant association between lower leg muscle mass and tinnitus. Additionally, multivariable analysis indicated that intracellular fluid levels tend to decrease as the duration of tinnitus increases. Given that total body fluid and intracellular fluid are indicative of body muscle mass27, the higher levels of these fluids in the non-tinnitus group suggest that sarcopenia may be a risk factor for tinnitus. Furthermore, the lower leg muscle mass might have the most significant impact on tinnitus, considering that skeletal muscle mass is greater in the lower body than in the upper body28. The link between tinnitus and sarcopenia could be attributed to functional changes in the brain. Suo et al. demonstrated that progressive resistance training is significantly associated with the functional connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus, which are key regions of the default mode network (DMN)29,30. The DMN is involved in self-referential mental processes during the resting state3,30,31 and is part of the triple network, which has been shown to be significantly related to tinnitus3,30. Considering the relationship between sarcopenia and the DMN, resistance training aimed at preventing sarcopenia may also be helpful for preventing tinnitus.

Moreover, some studies have demonstrated that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is significantly associated with resistance training in men, but not in women32,33. Based on these findings, sarcopenia is significantly related to lower BDNF levels in men, which may lead to altered functional connectivity in the DMN in the male population, potentially inducing tinnitus. Additionally, compared to male sarcopenia, female sarcopenia can be accompanied by hormonal changes after menopause34. In this study, we could not evaluate menopause due to a lack of information. Although females performed muscle training, their skeletal muscle can decrease after menopause34, probably leading to different sarcopenia-associated features in females. Further research is necessary to elucidate the precise relationship between sarcopenia and tinnitus, as well as the associated brain changes.

In this study, there was no difference in BMI among the groups when considering tinnitus and its duration. This finding diverges from those reported in other previous studies. It is important to note that BMI is associated not only with fat content, particularly visceral fat, but also with muscle mass35. Therefore, an elevated BMI may result from increased levels of either fat or muscle. Given that our results indicate a link between tinnitus and both central obesity and sarcopenia, BMI fails to accurately reflect an individual’s body composition in the presence of these conditions. Therefore, measures that more specifically assess visceral fat, such as trunk fat percentage and waist circumference, should be considered as potential risk factors for tinnitus rather than BMI.

BIA is commonly used to evaluate body composition10. However, it tends to yield different results for various ethnic groups36. Therefore, distinct equations should be applied for different ethnicities. Some recent studies have reported that the body composition of Asians and Koreans can be accurately evaluated using a recently developed equation and device10,37, one of which was applied in this study. Consequently, clinicians should consider these factors before assessing body composition and providing interventions.

This study revealed that tinnitus was associated with age and mean hearing level in both male and female populations, and was related to household income, depressive mood, anxiety, and dizziness only in the female group. Hearing loss is one of the major causes of tinnitus. Age-related degenerative changes in the brain and age-related hearing loss are also major causes of tinnitus1,4. Some previous studies have identified associations between tinnitus and factors such as patient income, physical health, and mental health1,38,39. These findings are consistent with our study, which reveals an association of tinnitus with age, household income, depressive mood, anxiety, and dizziness. Additionally, some previous studies about the association between psychological symptoms and tinnitus in each gender showed that females with tinnitus have more psychological and physical comorbidities and tinnitus in females was significantly associated with depressive mood or anxiety, while in males it was not40,41,42. Based on these previous studies and our results, tinnitus in females is more associated with psychological and physical symptoms, while in males, it is less associated with those symptoms.

The main limitation of our study was its cross-sectional design, which relied on a database from a previously conducted survey. Because the database lacked additional information, such as the characteristics and types of tinnitus, we were unable to determine the specific features of tinnitus. Given that subjective tinnitus is more common than objective tinnitus, there may be a relationship between upper-body obesity and subjective tinnitus. To clarify the characteristics of tinnitus associated with upper-body obesity, further studies with more comprehensive tinnitus information are required.

Another limitation of our study is the inclusion of both the acute tinnitus group and the chronic tinnitus group for evaluating tinnitus-related body composition. Since we could not evaluate the exact duration of tinnitus and whether the tinnitus is ongoing in each patient, and the number of participants in the acute tinnitus group was small, it was difficult to demonstrate the factors associated with tinnitus in the acute stage. Therefore, we conducted the analysis of tinnitus-related body composition by including both the acute and chronic tinnitus groups because about 80% of the acute tinnitus can progress to chronic tinnitus43,44, and some causes and risk factors are shared between both chronic and acute tinnitus1. However, since the neural networks and auditory pathways of patients with acute tinnitus are significantly different from those of patients with chronic tinnitus45, further studies with a larger number of acute tinnitus cases may be helpful in evaluating the factors associated with body composition in the acute tinnitus stage.

This study also had the limitation of including patients with mild hearing loss classified by WHO classification46. Since hearing level was significantly associated with tinnitus, we tried to control the hearing level. However, when using a 25 dB cutoff for defining hearing loss, the number of participants significantly decreased due to a higher proportion of hearing loss in older individuals. Therefore, we used a 40 dB cutoff for defining hearing loss and adjusted the hearing level for the analysis of the association between tinnitus and body composition.

Additionally, we were unable to establish causality between upper limb obesity and tinnitus due to the limitations inherent in cross-sectional studies. A prospective cohort study would be beneficial in clarifying the causality between these conditions.

Conclusion

Body composition was significantly associated with tinnitus in the male population, and central obesity was linked to chronic tinnitus in males. Furthermore, assessing the risk of central obesity in males with chronic tinnitus could be advantageous for early detection of central obesity, thereby mitigating additional cardiovascular risk.

Data availability

The data used in our study can be accessed through “https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_05.do”.

References

Han, B. I., Lee, H. W., Kim, T. Y., Lim, J. S. & Shin, K. S. Tinnitus: Characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. J. Clin. Neurol. 5, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2009.5.1.11 (2009).

Özbey-Yücel, Ü. & Uçar, A. The role of obesity, nutrition, and physical activity on tinnitus: A narrative review. Obes. Med. 40, 100491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obmed.2023.100491 (2023).

Lee, S. J. et al. Triple network activation causes tinnitus in patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A model-based volume-entropy analysis. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1028776. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1028776 (2022).

Adjamian, P., Hall, D. A., Palmer, A. R., Allan, T. W. & Langers, D. R. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in chronic tinnitus in the human brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 45, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.05.013 (2014).

Mennink, L. M., Aalbers, M. W., van Dijk, P. & van Dijk, J. M. C. The role of inflammation in tinnitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11041000 (2022).

Michaelides, E. M., Sismanis, A., Sugerman, H. J. & Felton, W. L. 3rd. Pulsatile tinnitus in patients with morbid obesity: The effectiveness of weight reduction surgery. Am. J. Otol. 21, 682–685 (2000).

McCormack, A. et al. Association of dietary factors with presence and severity of tinnitus in a middle-aged UK population. PLoS One 9, e114711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114711 (2014).

Gowri, S. M. et al. Distinct opposing associations of upper and lower body fat depots with metabolic and cardiovascular disease risk markers. Int. J. Obes. 45, 2490–2498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00923-1 (2021).

Chen, G. C. et al. Association between regional body fat and cardiovascular disease risk among postmenopausal women with normal body mass index. Eur. Heart J. 40, 2849–2855. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz391 (2019).

Yi, Y., Baek, J. Y., Lee, E., Jung, H. W. & Jang, I. Y. A comparative study of high-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for estimating body composition. Life (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/life12070994 (2022).

Branski, L. K. et al. Measurement of body composition in burned children: Is there a gold standard?. JPEN J. Parent. Enter. Nutr. 34, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607109336601 (2010).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Int. Med. 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Wasano, K., Nakagawa, T. & Ogawa, K. Prevalence of hearing impairment by age: 2nd to 10th decades of life. Biomedicines https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10061431 (2022).

Park, Y. H., Shin, S. H., Byun, S. W. & Kim, J. Y. Age- and Gender-related mean hearing threshold in a highly-screened population: The Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2010–2012. PLoS One 11, e0150783. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150783 (2016).

WHO Expert Committee. Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organ Tech. Rep. Ser. 854, 1–452 (1995).

Kim, K. K. et al. Evaluation and treatment of obesity and its comorbidities: 2022 update of clinical practice guidelines for obesity by the korean society for the study of obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes23016 (2023).

Bredella, M. A. Sex differences in body composition. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1043, 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_2 (2017).

Biro, F. M. & Wien, M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1499s–1505s. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B (2010).

Shuster, A., Patlas, M., Pinthus, J. H. & Mourtzakis, M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: A critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 85, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/38447238 (2012).

Vogel, M. A. A. et al. Differences in upper and lower body adipose tissue oxygen tension contribute to the adipose tissue phenotype in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103, 3688–3697. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00547 (2018).

Gómez-Apo, E., Mondragón-Maya, A., Ferrari-Díaz, M. & Silva-Pereyra, J. Structural brain changes associated with overweight and obesity. J. Obes. 2021, 6613385. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6613385 (2021).

van Galen, K. A. et al. Brain responses to nutrients are severely impaired and not reversed by weight loss in humans with obesity: A randomized crossover study. Nat. Metab. 5, 1059–1072. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-023-00816-9 (2023).

Dekkers, I. A., Jansen, P. R. & Lamb, H. J. Obesity, brain volume, and white matter microstructure at MRI: A cross-sectional UK biobank study. Radiology 291, 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019181012 (2019).

Wang, M. L. et al. Role of the caudate-putamen nucleus in sensory gating in induced tinnitus in rats. Neural Regen. Res. 16, 2250–2256. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.310692 (2021).

Lan, L. et al. Topological features of limbic dysfunction in chronicity of tinnitus with intact hearing: New hypothesis for ‘noise-cancellation’ mechanism. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatr. 113, 110459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110459 (2022).

Serra-Prat, M., Lorenzo, I., Palomera, E., Ramírez, S. & Yébenes, J. C. Total body water and intracellular water relationships with muscle strength, frailty and functional performance in an elderly population. J. Nutr. Health Aging 23, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1129-y (2019).

Janssen, I., Heymsfield, S. B., Wang, Z. M. & Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 year. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(89), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81 (2000).

Suo, C. et al. Therapeutically relevant structural and functional mechanisms triggered by physical and cognitive exercise. Mol. Psychiatr. 21, 1633–1642. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.19 (2016).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Is the posterior cingulate cortex an on-off switch for tinnitus?: A comparison between hearing loss subjects with and without tinnitus. Hear. Res. 411, 108356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2021.108356 (2021).

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Schacter, D. L. The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1124, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.011 (2008).

Church, D. D. et al. Comparison of high-intensity versus high-volume resistance training on the BDNF response to exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(121), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00233.2016 (2016).

Forti, L. N. et al. Dose-and gender-specific effects of resistance training on circulating levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in community-dwelling older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 70, 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2015.08.004 (2015).

Messier, V. et al. Menopause and sarcopenia: A potential role for sex hormones. Maturitas 68, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.01.014 (2011).

Kyle, U. G., Schutz, Y., Dupertuis, Y. M. & Pichard, C. Body composition interpretation. Contributions of the fat-free mass index and the body fat mass index. Nutrition 19, 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00061-3 (2003).

Dehghan, M. & Merchant, A. T. Is bioelectrical impedance accurate for use in large epidemiological studies?. Nutr. J. 7, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-7-26 (2008).

Wu, C.-S. et al. Predicting body composition using foot-to-foot bioelectrical impedance analysis in healthy Asian individuals. Nutr. J. 14, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0041-0 (2015).

Langguth, B., Kreuzer, P. M., Kleinjung, T. & De Ridder, D. Tinnitus: Causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 12, 920–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70160-1 (2013).

De Ridder, D. et al. in Progress in Brain Research Vol. 260 (eds Winfried Schlee et al.) 1–25 (Elsevier, 2021).

Cederroth, C. R. & Schlee, W. Editorial: Sex and gender differences in tinnitus. Front. Neurosci. 16, 844267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.844267 (2022).

Niemann, U., Boecking, B., Brueggemann, P., Mazurek, B. & Spiliopoulou, M. Gender-specific differences in patients with chronic tinnitus: Baseline characteristics and treatment effects. Front. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00487 (2020).

Fioretti, A., Natalini, E., Riedl, D., Moschen, R. & Eibenstein, A. Gender comparison of psychological comorbidities in tinnitus patients: Results of a cross-sectional study. Front. Neurosci. 14, 704. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00704 (2020).

Vielsmeier, V., Santiago Stiel, R., Kwok, P., Langguth, B. & Schecklmann, M. From acute to chronic tinnitus: Pilot data on predictors and progression. Front. Neurol. 11, 997. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00997 (2020).

Wallhäusser-Franke, E. et al. Transition from acute to chronic tinnitus: Predictors for the development of chronic distressing tinnitus. Front. Neurol. 8, 605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00605 (2017).

De Ridder, D., Vanneste, S., Song, J. J. & Adhia, D. Tinnitus and the triple network model: A perspective. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 15, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2022.00815 (2022).

Olusanya, B. O., Davis, A. C. & Hoffman, H. J. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull. World Health Organ. 97, 725–728. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.19.230367 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number : HC19C0128).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-Y.H. wrote the manuscript and conducted statistical analysis. S.-Y.L., M.-W.S., and J.H.L. prepared figures and tables. M.K.P. designed the study, supervised it, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, SY., Lee, SY., Suh, MW. et al. Associations between tinnitus and body composition: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 16373 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67574-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67574-w