Abstract

Securely dated archaeological sites from key regions and periods are critical for understanding early modern human adaptive responses to past environmental change. Here, we report new radiocarbon dates of > 42,000 cal years BP for an intensive human occupation of Gorgora rockshelter in the Ethiopian Highlands. We also document the development of innovative technologies and symbolic behaviors starting around this time. The evidenced occupation and behavioral patterns coincide with the onset and persistence of a stable wet phase in the geographically proximate high-resolution core record of Lake Tana. Range expansion into montane habitats and the subsequent development of innovative technologies and behaviors are consistent with population dispersal waves within Africa and beyond during wetter phases ~ 60–40 thousand years ago (ka).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The timing, routes, and behavioral contexts of the ultimately successful modern human dispersals out of Africa during the Late Pleistocene remain contentious1,2,3. Fossil and archaeological evidence from well-dated sites in key regions and Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) are sparse for this period, limiting the integration of emergent insights from genetic and paleoclimatic studies into discussions of human eco-geographic range and innovative behaviors4,5. The ‘early’ MIS 3 (60–40 ka) archaeological record in the Horn of Africa provides crucial insights into the ecological and behavioral conditions that drove modern human range expansions within Africa and beyond. The northwestern Ethiopian plateaus, characterized by ambient biodiversity and predictable climate patterns, are emerging as particularly focal for their role in shaping Late Pleistocene demographic structures and dispersals6,7,8. Evaluating the specific ecological contexts and adaptive traits that mediated the pace, directions, and departure points of dispersal events out of this putative subregion9, as well as testing proposed heuristic models on these10, however, remain a challenge. The main reason for this is the paucity of well-dated sites near high-resolution climate archives in regions that straddle the major dispersal routes out of Africa11,12.

Recent research efforts have led to the successful dating of Ethiopian sites with evidence of early MIS 3 human occupation13,14,15. However, their remoteness from the relevant high-resolution paleoclimate archives–namely Lake Tana, and Chew Bahir5,12–obfuscates attempts to link the concomitant modern human responses to local climatic conditions16. Given that most late Middle Stone Age (MSA) sites in the region were excavated over half a century ago17,18,19, revisiting previously excavated sites and collections becomes as important as probing new ones to keep up with relevant theoretical and methodological advances20,21,22,23,24.

The bulk of our current understanding of MIS 3 human adaptive patterns in the Horn of Africa comes from a few cave/rockshelter sites with reliable chronometric control. At Porc-Epic cave along the foothills of the plateaus overlooking the southern Afar Rift, the MSA dating ~ 50–39 ka is characterized by the predominance of points often made on obsidian, faunal and human remains, several thousand worked ochre pieces, and a few hundred perforated shell beads21,24. The pertinent MIS 3 material from Goda Buticha, ~ 30 km SW of Porc-Epic, is dated to 43–34 ka and similarly contains a large number of retouched points, most on obsidian, and engraved ostrich eggshell fragments14,21. At Fincha Habera, high in the southeastern Ethiopian plateaus, the MSA spans ~ 46–31 ka and contains lithic tools predominantly made on obsidian, including numerous points, ochre pieces, and ostrich eggshell beads15. At Mochena Borago, the securely dated MSA is 50–37 ka, with older layers likely extending to the beginning of the MIS 37,13. The older stratigraphic units (~ 50–47 ka) at this site have yielded abundant points mostly made on obsidian while a small number of non-geometric backed pieces also appear precociously13. Points and scrapers decrease in number, while scrapers become the most abundant retouched tools in the overlying units (46–44 ka). The youngest MSA (43–37 ka) was deposited following a reoccupation of the site ~ 43–42 ka, following a hiatus, and broadly mirrors the patterns prior13. Ochre is documented from all units at this site13. A few other sites in Somalia (e.g., Midhishi 2 and Gud-Gud) potentially sample the early- to mid-MIS 3 MSA although their age estimates and site contexts require a revisit17.

These MIS 3 occupations span diverse topographies and ecologies that range from rift margins (1384 m) to plateaus (2214 m) and mountain summits (3469 m). The behavioral flexibility of denizens of these MIS 3 sites is attested by the diverse core reduction and tool production methods employed, including the Levallois, preference for high quality raw material, and the shared tradition of pigment use and beads while the deliberate marking of objects is unique to Goda Buticha. The production of points, often on obsidian, was important in all sites and assemblages although functional analyses on these are lacking for most sites. A comprehensive investigation of the timing and mode of behavioral patterns in the region is limited by the dearth of long sequences with secure chronologies. MIS 3 archaeological occurrences that potentially extend beyond the radiocarbon dating range are extremely rare in the region. Where they are reported13, the restricted applicability of luminescence dating techniques (e.g., OSL) due to the region’s volcanic history means that alternative dating techniques have yet to be explored.

One of only two excavated MSA sites across northwestern Ethiopia and Eritrea9, the age and place of the Gorgora record within the regional archaeology long remained uncertain17,18. Consistent with the patterns summarized above, the Gorgora MSA is characterized by the presence of different tool production methods, the predominance of points, and pigment use while beads are absent. New radiometric dates from Gorgora rockshelter now provide age constraints for the occupation of this shelter in the northwestern Ethiopian highlands during a MIS 3 stable wet phase in the local climate record5,25. We find a marked increase in site occupation intensity and the appearance of innovative technologies and symbolic behaviors during and after the dated interval. We infer that these behavioral and settlement shifts were correlated with the paleoclimate pulses in the high-resolution seismic and core record of Lake Tana, sampled within ~ 5 km of the shelter5,25. Our results are compatible with evidence and predictions for the successful geographic expansion locally of behaviorally innovative modern humans to montane habitats during MIS 310,15,26,27. The results have implications for the suggested early MIS 3 dispersals, in multiple pulses, of modern humans within the region and beyond1,28,29,30.

Results

Site context and chronology

Gorgora rockshelter was discovered and excavated in 1942 by a British WWII officer, and two unnamed Ethiopian soldiers, serving in the Abyssinian Campaign31. A total of 1320 lithic, worked pigment, and pottery remains were recovered and subsequently exported to Kenya where they were only briefly described by LSB Leakey32. Despite the limited study, no chronometric age estimate, and no follow-up visit to the site, the Gorgora archaeological record has frequently been incorporated into discussions of the Horn of African archaeology17,18,33,34. Against this backdrop, Gorgora rockshelter was rediscovered by one of the coauthors (O.M.P) in 2002, although this was not reported anywhere. The results presented here thus follow the site’s independent rediscovery in 2023 by Y.S. and G.A.F., as part of a renewed research interest in past lakeside adaptation stimulated by accumulating local paleoclimate data12,34,35.

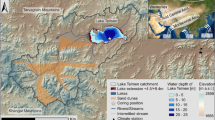

Gorgora rockshelter (~ 1930 m) is located on the Narna trachytic-basaltic inselberg which rises ~ 70 m above the adjoining plains, about 1 km from the northern shores of Lake Tana (Fig. 1). The site affords a strategic view of the surrounding vast plain, which likely provided an advantage to its prehistoric inhabitants. The current dripline is located nearly halfway into the completely excavated ~ 5 × 2.4 m living floor (Fig. 2). The lack of detailed fieldnotes and comprehensive section drawings from the original work led to skepticism around stratigraphic integrity and sampling control17,18. The validity of named industries used in the original description of the material was similarly questioned17,18. Initial failure to relocate the site discouraged recontextualization plans, obscuring the site’s proper place within the broader regional archaeological context.

Site locations and views. Ethiopian early- to mid-MIS 3 archaeological sites (inset map: Mochena Borago, Fincha Habera, Goda Buticha, Porc-Epic), and a satellite image showing the locations of Gorgora rockshelter and the Lake Tana paleoclimate core within the NW Ethiopian highlands (a). The Narna inselberg (view W) with the arrow indicating the shelter’s location and the red box a person for scale (b). View of the adjoining Dembia plain from inside the rockshelter (c).

Site context. Planview and ‘profile’ of the 1942 excavation (a, b). Remnant sediment (arrow), weathering rind, rockfall, and inward wall narrowing of the 1942 excavation (c). Schematic stratigraphic section of what would be the E wall with the artificial horizontality of the 1942 excavation (d); red star indicates charcoal sample positions from within the remnant sediment.

Following rediscovery, we rectified the plan view and ‘section’ of the 1942 excavation31. An unexcavated shallow (~ 13 cm) witness balk of organic-rich soil atop a bedrock incision in the narrow back of the shelter represents the original surface (Fig. 2). This humus layer is different in color and composition from the ashy silt associated with the MSA31. Additional indicators such as the contrast in weathering rinds on the shelter walls, and initial descriptions of the sedimentary succession enabled us to further establish the original surface level. Rockfall at the shelter ‘entrance’ marks the base of the 1942 area C excavation at a ~ 90 cm depth, which further supports our positioning of the original surface level. The progressively narrowing walls at the base of the main excavation area measure ~ 38 cm apart (Fig. 2), confirming our reconstruction of the base of the 1942 excavation31. Finally, this excavation base contains large and hollow calcareous nodules (≥ 50 mm in diameter) unique to the bottom layer of the sequence than the granules and small pebbles (4–20 mm) in the remnant sediment (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). These various references support the conclusion that the excavated sequence was only ~ 1.8 m from surface to base, which is exactly half of what was claimed in the original report31. Because the excavated section was divided into 12 equal levels31, we judge the excavation spits to be 15 cm (½ft) each (Fig. 2).

We identified a patch of sediment wedged in a crevice close to the base of the inclined S wall of the 1942 excavation (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Excavation of this small (23 × 8 × 6 cm; length, breadth, depth) deposit revealed that all finds were recovered in a horizontal position and with no preferred orientation or evidence of disturbance. These were also compatible in adherent matrix and typological composition with the previous MSA collection–particularly L9 and L10–which we subsequently revisited (Supplementary Figs. S1–S2 online). The remnant sediment is a yellowish brown (10YR 5/4 on the Munsell soil-color charts) ashy silt. The volcanic origin31 of the ash can now be rejected as it lacks any glass shards, jagged rock fragments or diagnostic minerals.

Two charcoal fragments were collected from a ~ 5 cm depth difference within the excavated remnant sediment and yielded AMS14C dates of 42,584–42,116 and 42,930–42,375 cal years BP (2σ) (Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S3 online). Charcoal samples analyzed using MICADAS-AMS procedures provide very reliable dates within a ~ 50 ka limit. Although there is a slight overlap between our two dates at 2σ level, the fact that these samples are derived from different depths within an undisturbed context means that they can be confidently considered distinct. The top of the sampled remnant sediment was judged to be just over 1.2 m below the surface (Fig. 2). This places the remnant sediment securely within Level 9 (L9) of the original excavation. L9 and the two underlying levels (L10–L11) have yielded points similar to those from the overlaying MSA layers. The Lake Tana paleoclimate record for the dated and broader period shows an increasingly wetter condition with an overspill at ~ 42 ka and consistently higher lake levels until the excursion of drier conditions after 35 ka. The relatively stable conditions contrast with the earlier part of the MIS 3 (60–50 ka) in the Tana record, which is characterized by a predominantly dry phase with the exception of a brief but pronounced wet excursion ~ 54 ka12,25.

Inferred occupation intensity and duration

A total of 873 lithic artifacts were originally reported from the MSA layers (L4–L12) in the Gorgora sequence, with L5 accounting for ~ 22% of the total count, followed by L9 at ~ 16%32. Over 62% of the debitage component of the original collection has since been lost, although this did not affect our current analysis. The available assemblage (n = 336) comprises all retouched tools and utilized pieces, cores, and a small portion of the debitage. Cryptocrystalline silicate rocks (chert, chalcedony, jasper) dominate the raw material types (at ~ 91%). These rocks occur as pebbles and blocks embedded within exposed rock beds along nearby streams. Silicified tuff and limestone together account for just < 5% while basalt makes up ~ 2.6% of the total available count; obsidian is represented by a single piece.

Artifact density per volume of sediment is several thousand folds higher in the remnant sediment than in any of the 1942 excavation levels. Half of the lithic finds from the remnant sediment are < 20 mm in maximum dimension (Supplementary Fig. S2 online), lending support for previous suspicion that a large volume of small debris was discarded as uncollectible in 194218. For this reason, we included in the L9 assemblage only six out of 133 lithic artifacts (two large blades, two core-preparation flakes, including a débordant, and a unifacially retouched point) from our excavation as these would have certainly been collected by the original excavator. Even when the newly recovered pieces are excluded from the count, there is a > 200% increase in artifact count in L9 as compared to the underlying levels. Artifact count remains high for all overlying layers except L6, which still has a higher count than those below L9.

The density of artifacts at a given site can be used as a proxy for occupation intensity and duration36. Notwithstanding the complexities associated37, these variables can be generally understood as the number of people utilizing a unit area across a given length of time. The number of artifacts per unit volume of sediment excavated, the relative abundance of lithic artifact forms, and raw material types are commonly used for a coarse understanding of settlement patterns. Measuring occupation intensity and duration more powerfully requires data on sediment accumulation rates across specific time spans along a stratigraphic sequence. Well-resolved chronological and stratigraphic data are unfortunately extremely sparse in most eastern African early MIS 3 contexts, particularly those excavated several decades ago11. As a result, assessment of occupation dynamics as proxies for diachronic socio-demographic patterns in the region involve certain estimates36.

Artifact count is lowest in the bottommost stratigraphic level, which has yielded only eight pieces. This increases slowly up the stratigraphic sequence until it shows spikes of 97% from L10 to L9, and > 430% from L12 and L11 combined (Table 1). This dramatic increase suggests greater occupation intensity starting at the dated interval. Artifact count remains similar for the overlying MSA levels with a decrease only in L6 of 44% from the directly underlying level. To further explore the observed pattern, a sedimentation rate of 16.5 cm/kyr was calculated for the patch we excavated. Assuming a similar rate for each excavation level yields a substantial amount of variation in artifact accumulation rate across the sequence (rs = − 0.733, p = 0.038), ranging from 10.58 artifacts m-3/kyr for the lowermost level to 263 artifacts at the top (Table 1). A similarly significant (rs = − 0.817, p = 0.013) result is obtained without the six newly recovered pieces added to the L9 assemblage. These results suggest a marked increase in occupation intensity across the sequence, starting in L9.

Following Tryon and Faith36, we further assessed the relative abundance of retouched tools as a proxy for occupation duration. A higher retouched tool to artifact volumetric density ratio is expected for mobile hunter-gatherers while sites occupied for longer duration would have greater manufacturing debris. While lacking a temporal trend consistent across the stratigraphic sequence, the dated assemblage shows a noticeably lower count of retouched tools relative to artifact volumetric density as compared to the underlying L10 assemblage. This ratio continues to drop up the stratigraphic sequence except in L6, which contains the highest number of retouched points other than L10 (Table 1). Removing the L6 assemblage from the comparison yields a significant positive correlation (rs = 0.738, p = 0.049) in which retouched tool count relative to artifact density decreases up the sequence. Additional measures of occupation intensity36 could not be employed in the current study due to the nearly exclusively local origin of lithic raw materials and the extremely small number of cores (n = 3) in the pooled assemblages.

Innovative technologies and symbolic behaviors

The presence of foliate/subtriangular points with thinned bases dictated Leakey’s32 classification of the Gorgora MSA assemblage as “Stillbay”, a distinct techno-cultural period named after a site in southern South Africa. The morphological similarities between the Gorgora and the Still Bay points–typically the straight or gently curved sides with elliptical or pointed bases–are indeed striking (Fig. 3). However, given the current recognition of the Still Bay as a distinct regional industry that incorporates discrete temporally and geographically constrained logistic, foraging, technological, and behavioral elements, attribution of the Gorgora points to this named industry appears unbefitting. Instead, a context-specific consideration promises better insights38.

A sample of Gorgora points showing the typically foliate/(sub-)triangular shapes, proximal thinning, and diagnostic impact fractures: burin-like (a, b, f), unifacial spin off > 6 mm (d), and bending-initiated, hinge-terminating fracture on the ventral side of the distal end (e). Pieces d-f are from the ≥ 42 ka levels. A selection of the worked ochre pieces from the Gorgora MSA sequence (g).

Retouched points (n = 122) represent the single dominant typological class, making up 53.5% of the non-debitage portion of the pooled MSA material. Scrapers and backed pieces are rare (< 10%), with the latter appearing only after L9 and represented by less than a dozen pieces in any of these levels. The percentage of points is the highest in L10 (~ 27%), dropping to 17% in L9 and to 15–5% in the overlying levels except in L6. (Table 1). Points as a percentage of retouched tools also show a progressive decrease up the stratigraphic sequence. Mean point dimensions do not show a statistically significant temporal pattern (rs = 0.595; p = 0.138) across the sequence; nor does tip cross-section area (TCSA) (Kruskal–Wallis H test: p = 0.628). There is also no significant difference in the dimension of points from the older (L11-L9) versus younger (L8-L4) assemblages (Mann–Whitney U test: p = 0.817 for length; 0.307 for width; 0.325 for thickness; Fig. 4). Given that points are often produced for use as hunting weapon tips and considered a diagnostic feature of the MSA18, the observed similarities support the inclusion of the respective material from all studied levels within the same technocomplex.

Violin-and-box plots of the Gorgora points: TCSA (top), and TCSP (bottom) values compared with ethno-experimental references with known weapon delivery mechanisms. Note the limited TCSA and TCSP ranges within the Gorgora assemblages, suggesting their affiliation with the same tradition. Not also their placement between experimental stabbing spears and mechanically propelled ethnographic projectiles and light-to-mediumweight javelins.

Most Gorgora points are subtriangular, with 44% typically foliate and (parti-) bifacially worked (Fig. 3). The predominance of ‘standardized’ points and the strategic location of the site were central to suggestions about the importance of hunting and the nature of site occupation18. The total lack of fauna in the assemblage, or the report thereof, prevents a further exploration of this hypothesis. Given this limitation, we assessed the suitability and potential use of the Gorgora points for hunting using point tip geometry (i.e., TCSA and TCSP [perimeter]), base modification, and impact damage. TCSA and TCSP do not show a statistically significant difference (Kruskal–Wallis H = 7.09; p = 0.419, H = 7.36; p = 0.392, respectively) across the Gorgora MSA levels. A pairwise comparison with ethnographic and experimental data for various hunting weapon systems (Fig. 4) shows that all Gorgora points fall outside the dart, arrowhead, light- to medium-weight ethnographic javelin, and experimental stabbing spear ranges in TCSA39,40,41,42,43. Point assemblages from L10, L6, and L5 show no statistical difference in TCSA with heavyweight hunting javelins currently used by hunting groups in southern Ethiopia (H = 1.954; p = 0.582; see SI for a pairwise comparison). TCSP values of the L4 points are indistinguishable from dart-tips (U = 50; p = 0.074), although the sample size from this level is small. No significant difference (H = 6.998; p = 537) in TCSP exists between all Gorgora points and the medium-weight, versatile hunting javelins, with the L7 and L9 point additionally indistinguishable with long-blade hunting javelins currently used by traditional hunter groups43.

Approximately 11.5% of the points (n = 14) exhibit tip damage attributable to projectile use, hence diagnostic impact fractures44,45. Of these, most retain transverse tip fractures and fractures with bending initiation and step termination (Fig. 3). Another 15.5% (n = 19) of the points also show evidence of proximal thinning, mostly via several bifacial or dominant dorsal removals, suggesting design for hafting.

We assessed the dimensional and tip geometry standardization in the Gorgora points using the coefficient of variation (CV) equation proposed by Erkens and Bettinger46. A quotient of standard deviation and mean, a CV of 1.7% is considered highly standardized to a degree achievable by humans while a value of 57.7% reflects the lowest degree of standardization, which can be broadly translated to a lack of consistent functional constraints and cultural rules guiding the technological production. The Gorgora points exhibit a high degree of standardization across all three linear size attributes plus TCSA (with a CV as low as 18–19% for length and width, Supplementary Table S2 online). These results may signify the social transmission of complex technical information. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the production of standardized points likely entailed the imposition of strict design principles that start with selecting the right kinds of blanks and envisaging their intended use. Labor-intensive toolkits, such as designed points, can be seen as reflecting a delayed return system47 wherein hunter-gatherers invest time and effort into activities that guarantee future survival, and potentially serve as buffers against unexpected ecological risks. The Gorgora points appear to hold such adaptive value by their design sophistication, implying innovative manufacturing and use.

Leakey32 originally reported the presence of an unknown number of pigments among the Gorgora material. Our revisit of the available material identified sixteen red ochre pieces originating from most MSA levels; three more pieces were recovered by our excavation of the remnant sediment (Table 1). All ochre pieces display distinct signs of anthropogenic alteration, such as edge rounding and macroscopic striations. The pieces also vary in shape and size— from rounded to tabular, and from a few centimeters in diameter to fist-size. (Fig. 3). Given the Narna inselberg does not contain any geological ochre source, the finds must have been transported into the site from different sources. The identified traces on these worked ochre pieces are compatible with an economized extraction of powder. We interpret the use patterns at the site as indicative of symbolic culture24. Powder carefully and repeatedly extracted from the ochre nodules could be used to make pigments applied to body parts for adornment, but also as sunblock and/or insect repellent. The symbolic use of ochre may have conferred early modern human populations adaptive benefits by fostering group identity and intergenerational kinship48. The extraction, transportation, and processing of ochre often involves complex processes, thus rendering it a useful proxy for complex behavior entailing scheduling and trip coordination49. Ochre power was also used as a loading agent in the production of prehistoric compound adhesives needed for hafting stone tools49. The traces of exploitation on the Gorgora ochre pieces attest to the careful production of powder for symbolic and, perhaps also, utilitarian purposes.

Discussion

A comprehensive understanding of early modern human adaptation to diverse environmental conditions requires high-resolution data from natural archives as well as geographically proximate archaeological localities. With contrasting topographies and stable ecotones, the northwestern Ethiopian highlands are emerging as important Late Pleistocene human refugia8,9,10,16. Within these highlands, the largest freshwater body of Lake Tana and its environs likely promoted relatively persistent biomes that sustained humans during fluctuating climatic conditions. High-resolution seismic and core data suggest that this basin likely offered a relatively stable resource base throughout much of the Late Pleistocene8,12,25. However, the absence of dated Pleistocene sites in the region had long obscured its role in the survival of prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations. The first radiometric dates from Gorgora confirm human habitation of the Lake Tana area extending back to at least the earlier part of MIS 3, with an increase in occupation intensity and duration commencing ~ 42 ka, during a stable wet phase reflected in the local core record. The presence of comparable MSA artifacts throughout the Gorgora MSA deposit suggests repeated, if not continuous, occupation of the site. We infer that the variability in site occupation and behavioral patterns across the Gorgora MSA cultural sequence was linked not only to the local climate fluctuation but also to the incipient or pronounced ecological plasticity of the inhabitants8,12,16.

We interpret the cultural record from the shelter as representing relatively short-lived occupations by groups with an MSA technocomplex, and that the site was likely not inhabited long before the dated layer. This view is further supported by the presence in the oldest cultural layers of large nodules of carbonate concretion, which must have formed due to an increase in the wetness of the inselberg. A similarly wet episode with the lake’s overspill took place ~ 54 ka12. However, because the overlying excavation levels do not exhibit carbonate formation comparable to the lowermost levels, and because there is no alteration of sedimentary facies, the shelter’s occupation might not have extended to that age. The dated and sub-42 ka levels at Gorgora, therefore, suggest occupation of the shelter near the onset of the stable wet episode in the local paleoclimate, starting around 42 ka12.

Lake Tana’s paleoclimate record further shows that the MIS 3 stable wet episode continued until 35 ka, after which there was a return to arid conditions12,25. The continued occurrence of archaeological material throughout the Gorgora MSA sequence suggests that the stable biome, a mosaic landscape with topographic gradient, a large freshwater body, wetlands, and dry evergreen montane forest, made the area conducive to persistent hunter-gatherer adaptation.

Gorgora’s strategic location and high proportion of standardized points were considered by Clark18 indicative of its occupation as a ‘specialized hunting camp’. While recognizing the predominance of retouched points, we call attention to several lines of evidence that challenge such categorization. Due to the limited documentation of the initial excavation, an assessment of the spatial patterning of activities as a proxy for the duration and activity type at the site is moot. However, the presence of all stages of knapping activities, the predominance of debitage relative to retouched tools, and the almost exclusive use of local raw materials argues against interpretation of the site as a short-term, specialized hunting camp. As opposed to mixed or residential sites, hunting camps are commonly dominated by finished products, often made on non-local raw materials. Hearths are similarly uncommon in short-term hunting camps. Whereas the presence of charcoal in our excavated sediment cannot prove the presence of hearth, it does support anthropogenic combustion. Importantly, the high density of artifacts–including large debitage and small manufacturing debris – from such a small volume of sediment argues against the suggested short-term occupation and specialized hunting-camp nature of the Gorgora MSA (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). The lakeside location of Gorgora rockshelter would have reduced the need for frequent seasonal mobility as game animals would still be available near such a large body of water during dry seasons, in addition to the alternative freshwater food resources. Moreover, while the design- and use-related aspects of points in some of the layers indicate hunting with the help of javelins, the presence of other retouched tools suggests additional activities such as hideworking, woodworking and cutting/sawing.

Mastery of projectile technology is thought to have promoted early human adaptive plasticity within local ecosystems and range expansion beyond Africa50. Other MSA sites in the Ethiopian Rift basin have yielded point assemblages that similarly suggest use as projectile weapon tips51,52. The bifacial points from the Porc-Epic MSA were specifically shown to be statistically indistinguishable from North American darts51, although this weapon system is not known from an African context53.

The presence of worked ochre in the dated as well as most overlying MSA layers attests to the behavioral complexity of denizens of the rockshelter. The signs of conserved utilization and lack of an ochre quarry in the shelter’s vicinity suggest that it was transported from afar and likely used, among other things, as part of cultural rituals that enhance social bonding24,54. Ochre was also widely used in making adhesives during the MSA49. Establishing the exact function of archaeological ochre requires detailed analyses, including a microscopic examination of pieces that retain adherent hafting traces. Regardless of whether single or multiple purposes were served by the Gorgora ochre pieces, the observed traces of utilization coupled with the common association of ochre with symbolic culture points to complex human behavior. For instance, the use of ochre in the production of compound adhesives requires knowledge of the properties, proportions, or recipes, and the expected final product of this transformative process, all underscoring the cognitive ability of those involved. Additionally, ochre may have been utilized for body painting, serving purposes such as symbolic expression or as sunblock/insect repellent24,48. The Gorgora evidence thus expands the previously known geographical range of innovative early MIS 3 populations and their symbolic behaviors in the region beyond the Rift Valley and its margins55,56.

The northwestern parts of Ethiopia are emerging as critical in evaluating existing models about population structure, behavioral innovations, and ecological conditions that influenced Later Pleistocene hominin migration out of Africa8,9,16. A part of the largest continuous high-altitude landmass on the continent – sometimes dubbed the ‘Roof of Africa’– the northwestern mountains in the Amhara Region contain Ethiopia’s highest peaks at ~ 4550 m. The rugged mountain summits here are punctuated by plateaus, often abruptly. The plains surrounding Lake Tana represent one such plateau within the northwestern mountains (Fig. 1). The complex and heterogenous topographies in such highlands would have created diverse temperature and precipitation gradients offering early humans and other generalist species broad ecological ranges57. Such unique ecotones would have ameliorated extreme paleoclimatic conditions and made the broader region both a viable destination and transit route for early modern human populations traveling from the Rift basin towards the Nile, then further to the Levant, or into the Afar Rift and onward to southern Arabia across the strait of Bab-al-Mandeb. In sum, Lake Tana and its surrounding landscape likely hosted repeated stable human settlements and may have served as a launching pad for dispersals to various directions8. With its relatively continuous cultural sequence and new radiometric dates, the Gorgora archaeological record now provides a rare opportunity to study the technological and other behavioral innovations that fostered human adaptation to a highland setting during the MIS 3 climatic phase, which is a relatively poorly understood period in much of Africa.

The new dates and inferred settlement and behavioral patterns reported here are consistent with the picture from most MIS 3 sites that are either less intensively occupied or completely abandoned starting with the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum as early as 33 ka13,14,15,21,55,56. Most of these sites and the broader ecozones they represent were reoccupied only following improved climate condition of the African Humid Period, often with the Levallois technology continuing into the Holocene14,58. The present results from the Gorgora MSA are compatible with the suggested expansion of early modern humans out of the Rift and into montane habitats during the earlier part of MIS 326,27,28. The results also help integrate into the modern literature a site excavated 80 years ago and will inspire more research in this critical but understudied region of the Horn of Africa.

Methods

Samples

The pooled Gorgora assemblage includes lithic artefacts, potsherds, and worked ochre pieces. More than half of the previously reported debitage portion of the lithic assemblage has since been lost while at the Coryndon or the National Museum of Kenya (NMK), Nairobi. The remaining collection is currently housed in Nairobi, accessioned as material from Gorgora, Lake Tana in Abyssinia—then a popular exonym for Ethiopia. Each individual specimen is labeled R.S.L. Tana (Rock Shelter Lake Tana), sometimes twice—perhaps indicating a relabeling during an unreported revisit. Discussions are currently underway to repatriate the collections to their country of origin.

The total number of artifacts recovered from the 1942 excavation is difficult to ascertain. Leakey’s32 initial study reported a total of 1,310 lithic artefacts, worked ochre fragments, and potsherds. More than 82% of the lithic artefacts were classified as debitage, with three cores and five hammerstones identified in addition. Utilized flakes and formal retouched tools totaled 246, including 148 points, 36 backed pieces and 16 scrapers32 (resummed for correction here). Clark19, on the contrary, noted that there were only 873 artefacts and that “[t]here is no way of knowing how much debitage may have been left at the shelter”. Our analysis of the 1942 Gorgora collection identified a total of only 367 artefacts from the MSA levels, including the pigments, and other possible non-utilitarian items. To this was added a total of 133 pieces recovered from our renewed excavation of a remnant sediment now housed at the National Museum of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. The present research did not include the Later Stone Age and ‘ceramic Neolithic’ sub-assemblages from the substantially younger excavation levels. Some of these include points in larger numbers than previous reported32. However, the lack of any organic remains has made the dating of these impossible while the possibility of stratigraphic mixing also makes the comprehensive analysis of these sub-assemblages difficult17,33.

Our study of the available Gorgora lithic material included the identification of raw material types, and the documentation of formal artefact typology, support form, cortex cover, striking platform type, and edge modification. Hammer- and shaping techniques were inferred from the prominence of the bulb of percussion and retouch scar patterns. A significant inverse relationship is expected between retouched tools and artifact volumetric density at sites occupied for longer durations, since the latter variable increases due to on-site artifact manufacturing activities36; although this may also be confounded by near-site knapping activities and transportation of (semi-) finished products to the site. Furthermore, in a settlement system where a portion of the artifacts was used and discarded away from a residential site, the recovered assemblage (i.e., artifact density) may not accurately capture the occupation span.

Written informed consent was obtained to publish the image of human participants.

Radiometric dating

AMS radiocarbon analysis was conducted on charcoal samples recovered from a remnant sediment in the shelter (Fig. 2). Charcoal samples were carefully recovered and secured in microcentrifuge tubes with snap caps. Samples were analyzed in the Curt-Engelhorn Centre for Archaeometry (Mannheim, Germany), using the MICADAS-AMS housed in the ancillary unit Klaus-Tschira Archaeometry Center. Pretreatment of samples used the ABA-Method (Acid/Base/Acid, HCl/NaOH/HCl). The insoluble fraction was combusted to CO2 in an Elemental Analyzer (EA), which was in turn converted catalytically to graphite. The 14C ages are normalized to δ13C = − 25‰59 and calibrated using the dataset IntCal20 and the Oxcal software. Calibration graphs were generated using the software OxCal v.4.4.260,61. The reported ages were calibrated with the 2-sigma standard deviation (95.4% probability).

Lithic analysis

Previously suggested temporal trends in techno-typological attributes relied mainly on the frequency and attributes of formal tool classes. Accordingly, points and backed pieces were examined more closely given the low frequency of other tool forms (e.g., scrapers). Similarly, because previous work highlighted the importance of the Gorgora shelter as a hunting camp site, a functional analysis of points was employed. Pointed pieces with steep unifacial retouch along the lateral sides, ‘becs’ with bilateral notching, and preforms retaining overly asymmetrical or irregular parts were excluded from categorization as points. On the other hand, unretouched points retaining base thinning and/or tip damage patterns consistent with use in a longitudinal fashion while hafted were included in our quantitative assessment. Points with transversely broken bases were not suitable for the collection of maximum width and thickness, and hence not included in the quantitative analyses.

Measuring prehistoric demographic change admittedly requires more data than artifact frequency and site abundance, the latter affected by visibility and research attention. Following Tryon and Faith36, we infer a) occupation intensity using artifact density per sediment volume; b) occupation duration using retouched tool to artifact density ratio; and c) the dimension of formal tools, namely points and backed pieces. In addition, we measured functionally relevant attributes on points as these would have been optimized51. Because raw material type and distance are substantially similar across the studied sequence, a comparison of local and non-local raw material frequency was considered unnecessary. The extremely small number of cores also precluded other analyses with implications for group mobility.

Tip cross-sectional geometry was assessed for points on which maximum width and thickness could be collected. Tip cross-sectional area and -perimeter (TCSA, TCSP) were calculated using the following formula41,51

Calculated TCSA values were statistically compared to data from North American and African ethnographic39,40,43 and experimental42 point assemblages used as reference samples for the different weapon types and mechanisms of delivery.

Artifact standardization was measured following Eerkens and Bettinger’s46 percentage of coefficient of variation (CV), obtained by dividing the standard deviation score by the mean value of the measured size variable multiplied by 100. Accordingly, a CV range between 1.7 and 57.7 percent reflects the degree of artifact standardization. CV percentage was calculated as standard deviation divided by mean times 100. A CV score of 1.7% represents the maximum standardization achievable in artifact production while a CV score nearing 57.7% reflects a standardization expected from a random production. The closer a value is to the former, the greater the degree of standardization.

Data availability

The source data generated is this study have been deposited in ZivaHub: Open Data UCT, an online data repository powered by Figshare for Institutions and accessible at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25375/uct.25801369. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Bergström, A., Stringer, C., Hajdinjak, M., Scerri, E. M. & Skoglund, P. Origins of modern human ancestry. Nature 590, 229–237 (2021).

Rito, T. et al. The first modern human dispersals across Africa. PLoS One 8(11), e80031 (2013).

Soares, P. et al. The expansion of mtDNA Haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 915–927 (2012).

López, S., Van Dorp, L. & Hellenthal, G. Human dispersal out of Africa: A lasting debate. Evol. Bioinform. 11, EBO-S33489 (2015).

Foerster, V. et al. Pleistocene climate variability in eastern Africa influenced hominin evolution. Nat. Geosci. 15, 805–811 (2022).

Beyin, A. Upper Pleistocene human dispersals out of Africa: a review of the current state of the debate. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 615094 (2011).

Brandt, S. A. et al. Early MIS 3 occupation of Mochena Borago Rockshelter, Southwest Ethiopian Highlands: Implications for late Pleistocene archaeology, paleoenvironments and modern human dispersals. Quat. Int. 274, 38–54 (2012).

Grove, M. et al. Climatic variability, plasticity, and dispersal: A case study from Lake Tana Ethiopia. J. Hum. Evol. 87, 32–47 (2015).

Kappelman, J. et al. Adaptive foraging behaviours in the Horn of Africa during Toba super eruption. Nature 628, 365–372 (2024).

Beyin, A., Hall, J. & Day, C. A. A least cost path model for Hominin dispersal routes out of the East African Rift region (Ethiopia) into the Levant. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 23, 763–772 (2019).

Blome, M. W., Cohen, A. S., Tryon, C. A., Brooks, A. S. & Russell, J. The environmental context for the origins of modern human diversity: A synthesis of regional variability in African climate 150,000–30,000 years ago. J. Hum. Evol. 62, 563–592 (2012).

Lamb, H. F. et al. 150,000-year palaeoclimate record from northern Ethiopia supports early, multiple dispersals of modern humans from Africa. Sci. Rep 8, 1077 (2018).

Brandt, S., Hildebrand, E., Vogelsang, R., Wolfhagen, J. & Wang, H. A new MIS 3 radiocarbon chronology for Mochena Borago Rockshelter, SW Ethiopia: Implications for the interpretation of Late Pleistocene chronostratigraphy and human behavior. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 11, 352–369 (2017).

Tribolo, C. et al. Across the gap: Geochronological and sedimentological analyses from the Late Pleistocene-Holocene sequence of Goda Buticha, southeastern Ethiopia. PLoS One 12, e0169418 (2017).

Ossendorf, G. et al. Middle Stone Age foragers resided in high elevations of the glaciated Bale Mountains Ethiopia. Science 365, 583–587 (2019).

Blinkhorn, J., Timbrell, L., Grove, M. & Scerri, E. M. Evaluating refugia in recent human evolution in Africa. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20200485 (2022).

Brandt, S. A. The upper pleistocene and early holocene prehistory of the Horn of Africa. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 4, 41–82 (1986).

Clark, J. D. The middle stone age of East Africa and the beginnings of regional identity. J. World Prehist. 2, 235–305 (1988).

Sahle, Y. Eastern African Stone Age. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.53 (2020)

Gossa, T., Sahle, Y. & Negash, A. A reassessment of the Middle and Later Stone Age lithic assemblages from Aladi Springs, southern Afar Rift Ethiopia. Azania: Archaeol. Res. Afr. 47(2), 210–222 (2012).

Leplongeon, A. Microliths in the Middle and later stone age of eastern Africa: new data from Porc-Epic and Goda Buticha cave sites Ethiopia. Quat. Int. 343, 100–116 (2014).

Sahle, Y., Morgan, L. E., Braun, D. R., Atnafu, B. & Hutchings, W. K. Chronological and behavioral contexts of the earliest middle stone age in the Gademotta Formation Main Ethiopian Rift. Quat. Int. 331, 6–19 (2014).

Ranhorn, K. & Tryon, C. A. New radiocarbon dates from Nasera Rockshelter (Tanzania): Implications for studying spatial patterns in Late Pleistocene technology. J. Afr. Archaeol. 16, 211–222 (2018).

Rosso, D. E., Regert, M. & d’Errico, F. First identification of an evolving middle stone age ochre culture at Porc-Epic Cave Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 13, 13261 (2023).

Roberts, H. M., Bryant, C. L., Huws, D. G. & Lamb, H. F. Generating long chronologies for lacustrine sediments using luminescence dating: A 250,000 year record from Lake Tana Ethiopia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 202, 66–77 (2018).

Schaebitz, F. et al. Hydroclimate changes in eastern Africa over the past 200,000 years may have influenced early human dispersal. Nat. Commun. Earth Envron. 2, 123 (2021).

Timbrell, L., Grove, M., Manica, A., Rucina, S. & Blinkhorn, J. A spatiotemporally explicit paleoenvironmental framework for the middle stone age of eastern Africa. Sci. Rep. 12, 3689 (2022).

Viehberg, F. A. et al. Environmental change during MIS4 and MIS 3 opened corridors in the Horn of Africa for Homo sapiens expansion. Quat. Sci. Rev. 202, 139–153 (2018).

Tassi, F. et al. Early modern human dispersal from Africa: Genomic evidence for multiple waves of migration. Investig. Genet. 6, 1–16 (2015).

Timmermann, A. & Friedrich, T. Late Pleistocene climate drivers of early human migration. Nature 538, 92–95 (2016).

Moysey, F. Excavation of a rock shelter at Gorgora, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. J. East Afr. Uganda Nat. Hist. Soc. 17, 196–198 (1943).

Leakey, L. S. B. The industries of the Gorgora Rock Shelter, Lake Tana. J. East Afr. Uganda Nat. Hist. Soc. 17, 199–208 (1943).

Barnett, T. F. The Emergence of Food Production in Ethiopia (BAR Publishing, 1999).

Firew, G.A. Archaeological fieldwork around Lake Tana area of northwest Ethiopia and the implication for an understanding of aquatic adaptation. (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bergen, 2014).

Lamb, H. F. et al. Late Pleistocene desiccation of Lake Tana, source of the Blue Nile. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 287–299 (2007).

Tryon, C. A. & Faith, J. T. A demographic perspective on the middle to later stone age transition from Nasera rockshelter Tanzania. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150238 (2016).

Kuhn, S. L. & Clark, A. E. Artifact densities and assemblage formation: Evidence from Tabun Cave. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 38, 8–16 (2015).

Shea, J. J. A generic MSA: What problems will it solve and what problems will it create?. Azania: Archaeol Res. Afr. 59, 160–172 (2024).

Thomas, D. H. Arrowheads and atlatl darts: How the stones got the shaft. Am. Antiq. 43, 461–472 (1978).

Shott, M. J. Stones and shafts redux: The metric discrimination of chipped-stone dart and arrow points. Am. Antiq. 62, 86–101 (1997).

Hughes, S. S. Getting to the point: Evolutionary change in prehistoric weaponry. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 5, 345–408 (1998).

Shea, J. J., Davis, Z. & Brown, K. Experimental tests of middle Paleolithic spear points using a calibrated crossbow. J. Archaeol. Sci. 28, 807–816 (2001).

Sahle, Y., Ahmed, S. & Dira, S. J. Javelin use among Ethiopia’s last indigenous hunters: Variability and further constraints on tip cross-sectional geometry. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 70, 101505 (2023).

Fischer, A., Hansen, P. V. & Rasmussen, P. Macro and micro wear traces on lithic projectile points: Experimental results and prehistoric examples. J. Danish Archaeol. 3, 19–46 (1984).

Sano, K. Hunting evidence from stone artefacts from the Magdalenian cave site Bois Laiterie, Belgium: A fracture analysis. Quarär 56, 67–86 (2009).

Eerkens, J. W. & Bettinger, R. L. Techniques for assessing standardization in artifact assemblages: Can we scale material variability?. Am. Antiq. 66, 493–504 (2001).

Woodburn, J. Egalitarian societies. Man 17, 431–451 (1982).

Hodgskiss, T. Complex Colors: Pleistocene Ochre Use in Africa. In Handbook of Pleistocene Archaeology of Africa: Hominin Behavior, Geography, and Chronology (ed. Hodgskiss, T.) 1907–1916 (Springer, 2023).

Wadley, L., Hodgskiss, T. & Grant, M. Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the middle stone Age, South Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9590–9594 (2009).

Shea J.J. & Sisk M.L. Complex projectile technology and Homo sapiens dispersal into Western Eurasia. Paleoanthropol. 100–122 (2010).

Sisk, M. L. & Shea, J. J. The African origin of complex projectile technology: An analysis using tip cross-sectional area and perimeter. Intl. J. Evol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/968012 (2011).

Sahle, Y. & Brooks, A. S. Assessment of complex projectiles in the early Late Pleistocene at Aduma Ethiopia. PLoS One 14, e0216716 (2019).

Lombard, M. & Shea, J. J. Did Pleistocene Africans use the spearthrower-and-dart?. Evol. Anthropol. 30, 307–315 (2021).

Henshilwood, C. S. et al. A 100,000-year-old ochre-processing workshop at Blombos Cave South Africa. Science 334, 219–222 (2011).

Assefa, Z., Lam, Y. M. & Mienis, H. K. Symbolic Use of terrestrial gastropod opercula during the middle stone age at Porc-Epic Cave Ethiopia. Curr. Anthropol. 49, 746–756 (2008).

Assefa, Z. et al. Engraved ostrich eggshell from the middle stone age contexts of Goda Buticha Ethiopia. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 17, 723–729 (2018).

Bailey, G. N., Reynolds, S. C. & King, G. C. Landscapes of human evolution: Models and methods of tectonic geomorphology and the reconstruction of hominin landscapes. J. Hum. Evol. 60, 257–280 (2011).

Ashkenazy, H. & Sahle, Y. An early Holocene Lithic assemblage from Dibé Rockshelter South-Central Ethiopia. J. Afr. Archaeol. 19, 57–71 (2021).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion reporting of 14 C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Bronk Ramsey, C. OxCal Program v3.5. University of Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (2020). Available at 232 www.rlaha.ox.ac.uk/oxcal/oxcal.html

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ethiopian Heritage Authority, the National Museums of Kenya, and our respective universities for research permits and support. We also thank the Amhara Region Culture & Tourism Bureau and colleagues at Gondar, Chuahit, and Gorgora for their kind facilitation of our field research. This work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number :150524) to YS and DDS. The Gorgora archaeological material were exported out of Ethiopia in the 1940s, without the knowledge and permission of concerned authorities. We hope that our renewed scientific interest in the area encourages a new initiative to repatriate the collections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and G.A.F. conceived the research. Y.S., G.A.F. and O.M.P. conducted fieldwork. Y.S. performed laboratory analysis and collected data. Y.S., G.A.F, O.M.P., D.D.S. and A.B. developed method and analyzed the data. Y.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahle, Y., Firew, G.A., Pearson, O.M. et al. MIS 3 innovative behavior and highland occupation during a stable wet episode in the Lake Tana paleoclimate record, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 17038 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67743-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67743-x