Abstract

Although auditory stimuli benefit patients with disorders of consciousness (DOC), the optimal stimulus remains unclear. We explored the most effective electroencephalography (EEG)-tracking method for eliciting brain responses to auditory stimuli and assessed its potential as a neural marker to improve DOC diagnosis. We collected 58 EEG recordings from patients with DOC to evaluate the classification model’s performance and optimal auditory stimulus. Using non-linear dynamic analysis (approximate entropy [ApEn]), we assessed EEG responses to various auditory stimuli (resting state, preferred music, subject’s own name [SON], and familiar music) in 40 patients. The diagnostic performance of the optimal stimulus-induced EEG classification for vegetative state (VS)/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS) and minimally conscious state (MCS) was compared with the Coma Recovery Scale-Revision in 18 patients using the machine learning cascade forward backpropagation neural network model. Regardless of patient status, preferred music significantly activated the cerebral cortex. Patients in MCS showed increased activity in the prefrontal pole and central, occipital, and temporal cortices, whereas those in VS/UWS showed activity in the prefrontal and anterior temporal lobes. Patients in VS/UWS exhibited the lowest preferred music-induced ApEn differences in the central, middle, and posterior temporal lobes compared with those in MCS. The resting state ApEn value of the prefrontal pole (0.77) distinguished VS/UWS from MCS with 61.11% accuracy. The cascade forward backpropagation neural network tested for ApEn values in the resting state and preferred music-induced ApEn differences achieved an average of 83.33% accuracy in distinguishing VS/UWS from MCS (based on K-fold cross-validation). EEG non-linear analysis quantifies cortical responses in patients with DOC, with preferred music inducing more intense EEG responses than SON and familiar music. Machine learning algorithms combined with auditory stimuli showed strong potential for improving DOC diagnosis. Future studies should explore the optimal multimodal sensory stimuli tailored for individual patients.

Trial registration: The study is registered in the Chinese Registry of Clinical Trials (Approval no: KYLL-2023-414, Registration code: ChiCTR2300079310).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acquired brain injury can result from cerebral hemorrhage, traumatic incidents, post-anoxic events, or other brain damage, leading to coma lasting for at least 24 h1. Following the coma period, these patients may transition to a prolonged state of disorder of consciousness (DOC), comprising two primary diagnostic categories: vegetative state (VS)/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS) and minimally conscious state (MCS). Patients in the VS/UWS category only regain their arousal systems, as evidenced by eye-opening, although they remain unresponsive to external stimuli and lack awareness of self and surroundings2. Those displaying limited but distinct self-awareness and environmental perceptions are classified as being in MCS3. Patients with DOC experience significant fluctuations in their arousal levels and associated consciousness, particularly those in VS/UWS or MCS4.

Sensory deprivation due to prolonged hospitalization, immobility, and social isolation is a major challenge for patients with DOC5. Various sensory stimuli, such as visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, taste, gustatory, and equilibrium inputs, serve as experimental awakening approaches to counteract sensory deprivation. This approach is based on the concept that sensory stimuli may potentially facilitate dendritic growth and improve synaptic connectivity6,7. Among these stimuli, auditory stimuli have garnered particular attention due to their persistence as the last sensory system to fade8. Auditory stimuli characterized by personal preferences and emotional valence are more likely to induce neural activity and behavior changes9. Current research has predominantly focused on the efficacy of auditory stimuli for DOC, including familiar music10, preferred music11, and the subject’s own name (SON)12, which have been shown to elicit arousal and attention more effectively than disliked music and white noise. Auditory stimuli, considered a potential tool in clinical practice, can provide supplementary information on the response ability of patients with DOC to external stimuli2. Research indicates that the auditory network can be reliably observed, aiding the differentiation between MCS and VS/UWS13. However, limited research has determined whether these auditory stimuli are uniformly effective in increasing arousal among patients. Ordinary auditory stimuli may not significantly increase cortical responses in patients with DOC, which may reduce the wakefulness effect and accuracy of distinguishing between VS/UWS and MCS. Hence, this study sought to compare cortical responses to three auditory stimuli in patients with DOC.

The Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing DOC and evaluating intervention effects14 but can be unreliable due to patient sensorimotor and executive deficits15. The misdiagnosis rate of patients with DOC based on clinical scales ranges from 37 to 43%15,16. Some patients with DOC have exhibited ‘covert awareness’ or ‘cognitive motor dissociation,’ where a lack of responsiveness does not necessarily indicate a lack of awareness17. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) studies18,19 have reported that 15–20% of patients with DOC who exhibit no obvious behavioral responses may still show signs of covert awareness through brain activity. Therefore, accurate and objective assessment tools relying on brain activity are essential for patients with DOC.

Recently, neurophysiological techniques have complemented behavioral assessments in detecting consciousness. EEG provides rich temporal information on cognitive operations with high sensitivity, being non-invasive, simple, and easy to administer20. The non-linear dynamics of EEG are important for investigating neural systems, surpassing linear approaches to spectrum analysis21. It quantifies spontaneous EEG fluctuations, revealing non-linear dynamics characterized by sudden, disproportional, and unpredictable changes22,23. Approximate entropy (ApEn)—currently applied in clinical practice for monitoring sensory stimuli on cerebral cortical activity and predicting prognosis in patients with DOC23—was used for complexity/irregularity quantification of the time series in this study.

Moreover, robust statistical methodologies, such as machine learning (ML), have been integrated into EEG studies to enhance diagnosis and prognosis at the single-participant level in patients with DOC24. Typically, a classifier is trained to optimally differentiate clinical labels based on brain data25. Subsequently, performance is assessed by comparing the classifier predictions with the actual diagnosis (e.g., CRS-R) when utilizing unseen data25. The novelty and advantage of our study lie in the integration of optimal auditory stimuli with deep learning for diagnosing patients with DOC.

This study aimed to determine the auditory stimuli eliciting higher ApEn values in specific brain regions compared with that in the resting state. This finding provides a basis for healthcare decision-making on the stimulus modality to facilitate auditory stimuli to awaken better and diagnose patients with DOC.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional, observational study was approved by the Human Subject Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Shandong University and registered in the Chinese Registry of Clinical Trials under the approval and registration codes KYLL-2023-414 and ChiCTR2300079310, respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family members or legal guardians. All research procedures were performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All associated patient data remained confidential.

Between October 2023 and February 2024, 58 patients with DOC admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation of the Second Hospital of Shandong University were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of VS/UWS or MCS based on the CRS-R, (2) age 18–85 years, and (3) no history of previous brain injury. The exclusion criteria were: (1) pre-existing known hearing loss, (2) uncontrolled active cerebral hemorrhage or intracranial hypertension, (3) severe cerebral atrophy and hydrocephalus, (4) diagnosis of locked-in syndrome, (5) severe spasticity causing electromyography (EMG) artifacts, and (7) absence of a record of skull fracture.

Data on demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, age, and days post-injury, were collected from eligible participants. The CRS-R26 was used to assess the consciousness state of patients across six subscales: arousal level, motor function, visual perception ability, auditory and language comprehension ability, expressive speech ability, and communication ability, totaling 23 items. The lowest-scoring item on each subscale represents reflexive behavior, while the highest-scoring item reflects cognitively mediated activity. Before the commencement of auditory stimuli, CRS-R scores were evaluated thrice by a professional rehabilitation physician to achieve an accurate clinical diagnosis. Subsequently, the average CRS-R scores were recorded.

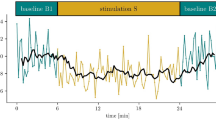

Experimental paradigm

According to Megha et al.6, short sessions (20 min) of multimodal stimuli are more beneficial for comatose patients. In this study, considering the patients’ tolerance, the auditory stimuli were of 15-min duration, and the total duration was maintained within 30 min. A 5-min resting-state EEG preceded three different 5-min auditory stimuli, each separated by 2 min of washout silence to prevent the cumulative effect of one stimulus on the next. EEG signals were recorded for three different auditory stimuli. The first audio file involved researchers conversing with the patient's family to identify the patient's preferred music. The second audio file was an audio recording of the patient's family calling SON. The third audio file played a selection of well-known and familiar music, specifically ‘Unforgettable Tonight.’ The three audio files were played in random order and were all played through headphones with a volume of 60–70 dB.

EEG recording

The procedures were performed in a noise-free ward (⁓26 °C) with no other electronic equipment. The procedure was conducted between 8:00 and 12:00 or 14:00 and 17:00 to minimize circadian influences on performance. Before the onset of auditory stimulation, patients in the supine position were assessed using a standard arousal facilitation protocol (i.e., deep pressure stimulation from the facial musculature to the toes) to maintain the wakefulness cycle.

EEG recordings were made using a wireless 16-channel digital EEG system (ZN16E, Chengdu, China) while the patients were awake and lying quietly and comfortably in the ward. The recording method was consistent with that used by Liu et al.20. EEG data from 19 scalp sites (channels FP1, FP2, F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2, F7, F8, T3, T4, T5, T6, Fz, Cz, and Pz) were recorded based on the international 10–20 system. All electrodes served as a reference to the linked earlobe lines. The prefrontal pole comprises FP1 and FP2; frontal cortex, F3 and F4; central cortex, C3 and C4; parietal cortex, P3 and P4; occipital cortex, O1 and O2; anterior temporal cortex, F7 and F8; middle temporal cortex, T3 and T4; and posterior cortex, T5 and T6.

The signals were digitised at a sample rate of 500 Hz, a bandwidth of 0.3–100 Hz, and a 12-bit AD conversion resolution. During the EEG recording, the patients were asked to relax, wake up, and close their eyes. First, the EEG signals were recorded in the patient’s resting state for 5 min. Second, three different auditory stimuli were presented via earphones. EEG signals were monitored online for signs of sleepiness and the onset of sleep (increased theta rhythms, K-complex waves, and sleep spindles) to maintain a steady level of vigilance. At any indication of behavioral sleepiness, EEG sleepiness, or both, the participant was awakened.

Artifact-free epoch selection was performed offline by an experienced physician through visual inspection of the recordings. Wireless digital EEG amplifiers and no power supply rooms were utilized to reduce electrical artifacts. The physician excluded EEG signals mixed with visible EMG signals and ocular artifacts. The stable EEG portion was recorded (i.e., the noisy portion at the beginning of the recording was discarded). Subsequently, this work referenced the EEG non-linear analysis method used in Wu et al.’s23 study, four EEG signal segments (resting state, preferred music, SON, and familiar music), each capturing approximately 32,768 consecutive data points (65.536 s) were selected for further analysis. Specifically, 50-Hz notch, 0.53-Hz low-frequency, and 70-Hz high-frequency filters in MATLAB (version R2021a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) were used to remove noise during data processing. Samples with severe EMG and ocular artifacts were excluded from the analysis.

Non-linear dynamics analysis

ApEn evaluates temporal irregularities in time-sequence data, is robust to low-frequency noise27,28, with the following Eq. (1–3):

Two input parameters, mode length m and tolerance factor r27, were specified for the computation. Typically, r is selected based on the standard deviation (SD) of the signal. Referring to Ferenets29 et al., r = 0.2 SD and m = 2 were set for this study. Increased ApEn values represent high complexity or irregularity, that is, enhanced non-linear cell dynamics or cortical network interactions23. Therefore, ApEn values can quantify EEG-derived information.

Classification

Referring to previous studies, the CFBNN model was introduced for classifying consciousness states30. In this study, the CFBNN classified the VS/UWS and MCS using ApEn values in the resting state and auditory stimulus-induced ApEn differences. The network comprises three parts: input, hidden, and output layers. For the input layer, four neurons corresponding to the four features of the ApEn values were used. Based on the ApEn values in the resting state and the optimal auditory stimulus-induced ApEn differences, univariate analysis was used to extract four input layer features with statistical differences between patients in VS/UWS and those in MCS.

Furthermore, the CFBNN with two hidden layers, which had 14 neurons, was constructed using the neural network toolbox tool in MATLAB. Finally, the output was the classification of the conscious state based on the current behavioral gold standard, the CRS-R. The training function was Levenberg–Marquardt, and the adaptation learning function was gradient descent with momentum. The mean squared error measured the difference between the output and the objective. The structure of the CFBNN model is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic of the CFBNN models. Feature 1: ApEn values of the prefrontal pole in the resting state. Feature 2: ApEn differences induced by preferred music in the central region. Feature 3: ApEn differences induced by preferred music in the middle temporal region. Feature 4: ApEn differences induced by preferred music in the posterior temporal region. CFBNN, cascade forward backpropagation neural network; ApEn, approximate entropy.

First, the DOC patients were screened using a training set consisting of 70% of the patients (n = 40) to identify the musical stimuli that most provoked the electrodes in the brain regions to become active, and the neural network was constructed using a single trial from the patients in the training set. Subsequently, all datasets (n = 58) were divided into training and test sets in a 2:1 ratio according to a computer-generated list of random numbers. In this work, the K-fold cross-validation method was used, which allows for internal validation and performance evaluation to be completed. When the dataset is small, overfitting and underfitting can be effectively avoided. In this work, the K-fold cross-validation method divides the training set into three folds: learning the classifiers using two folds and calculating the error values by testing the classifiers in the remaining fold.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed the distribution normality for age, days post-injury, and CRS-R total score. Summary statistics are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normal data and interquartile range for non-normal data. The independent-samples t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were performed to compare normal data and non-normal data, respectively. Categorical variables are presented as percentages.

Greenhouse Geisser corrections were used to prevent possible violations of the sphericity assumption in the repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Repeated-measures ANOVA identified the most effective stimulus among the three (preferred music, SON, and familiar music) for patients with DOC (VS/UWS and MCS), considering auditory stimuli as within-subject factors. Significant effects were examined using post hoc multiple comparison tests with Bonferroni correction.

ApEn values for patient groups were compared for auditory stimuli significantly affecting different regions of the cortex using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, which controls for the probability of Type I errors in multiple testing by adjusting the significance level α' = α /k (where k is the number of tests, and α refers to the original test); we obtained a Bonferroni correction of 0.05/6 = 0.0083 for each group. Moreover, effect sizes from the ANOVA models were calculated using the partial eta squared (ηp2) coefficient. Thresholds for partial η2 values are: small ≥ 0.01, medium ≥ 0.06, large ≥ 0.1431. Effect sizes were calculated to account for recent concerns in the physiological/biomedical literature about reporting only p-values, especially when making inferences based on binary thresholds32. Therefore, in this study, all inferences were based on the combination of p-value and effect size.

The area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve identified a cut-off value for the resting state prefrontal pole ApEn value, discriminating conscious and unconscious patients. The performance of the CFBNN model based on the ApEn values was evaluated using area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, accuracy, and specificity, respectively.

Figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.01 (San Diego, CA, USA). P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Shandong University (NO. KYLL-2023-414). All research procedures were conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the family members of the patients with DOC or their legal guardians.

Results

Comparison of general data in patients in MCS and those in VS/UWS

A total of 60 patients with DOC were initially screened, of whom 2 were excluded due to muscular artifacts. Ultimately, 58 patients were included, of whom 40 were included in the training set and used to select the optimal auditory stimuli, and 18 were used to evaluate the performance of the CFBNN classifier.

The baseline characteristics of the 58 patients are presented in Table 1. In the training set, patients in VS/UWS and MCS, respectively, were 75% (n = 20) and 80% (n = 20) male and had a median age of 57.5 and 65.5 years, duration post-injury of 77 and 45 days, and CRS-R score of 4 and 9 (P > 0.05). The patient flowchart is shown in Fig. 2.

Effects of auditory stimuli on ApEn values

The mean ApEn values for different stimuli are listed in Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 3. Regardless of the patients’ state, cortical activity increased with preferred music compared with that in the resting state, as measured by ApEn values. For patients in VS/UWS, activation was observed only in the prefrontal pole lobe (P = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.091) (Fig. 3a). Conversely, for patients in MCS, preferred music activated more regions of the cerebral cortex in the central (P = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.164), anterior temporal (P = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.225), middle temporal (P = 0.005, partial η2 = 0. 209) and posterior temporal electrodes (P = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.204) (Fig. 3b). However, ApEn values were comparable between SON and familiar music and those in the resting state (P > 0.0083).

Mean ApEn values and group comparability of ApEn values. Mean ApEn values for patients in VS/UWS (a) and those in MCS (b) during different stimuli. Group comparability of ApEn values at resting state (c) and preferred music-induced ApEn differences in patients with VS/UWS and MCS (d). ApEn, approximate entropy; MCS, minimally conscious state; SON, subject’s own name; VS/UWS, vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome.

Group comparability of ApEn values

Comparisons of ApEn values between patients in VS/UWS and those in MCS in the resting state and with preferred music are detailed in Table 3 and Fig. 3. The resting state ApEn values of patients in MCS in the prefrontal pole were significantly greater than those of patients in VS/UWS (P < 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 3c). Patients in MCS exhibited greater preferred music-induced ApEn differences than those in VS/UWS, particularly in the central, middle, and posterior temporal lobes (P < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 3c).

Subsequently, the resting state ApEn values of the prefrontal pole and preferred music-induced ApEn differences in the central, middle temporal, and posterior temporal electrodes were incorporated in the CFBNN classifier.

Classification performance

The confusion matrices and ROC curves are shown in Fig. 4. The prefrontal pole ApEn values of patients in the VS/UWS and MCS showed significant differences only in the resting state (P < 0.05), and the prefrontal pole of both groups was activated in response to their preferred music. The optimal cut-off value for ApEn values of the prefrontal pole in the resting state was determined as 0.77 with 61.11% (35.75%, 82.70%) accuracy and was used to distinguish between patients in VS/UWS and those in MCS using the training set. Further verification of the test set revealed an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.625 (0.370, 0.837), 58.33% (27.67%, 84.84%), and 66.67% (22.28%, 95.67%), respectively. In the CFBNN model, K-fold (k = 3) cross-validation was used to complete the internal validation and performance evaluation. The three machine learning models constructed had similar classification accuracies for VS/UWS and MCS states, with AUCs ranging from 0.766 to 0.909, accuracies ranging from 77.78% to 88.89%, sensitivities ranging from 81.82% to 87.50%, and specificities ranging from 71.43% to 100.00%. These results indicate that the classifier using the CFBNN algorithm can better recognize the state of consciousness of DOC patients.

Confusion matrix and ROC curves. (a): ApEn values of resting anterior frontal pole to differentiate ROC curves, CFBNN fold 1 ROC curves, CFBNN fold 2 ROC curves, CFBNN fold 3 ROC curves for VS/UWS and MCS. (b): Confusion matrix distinguishing between VS/UWS and MCS for the four mentioned above. ApEn, approximate entropy; AUC, area under the curve; CFBNN, cascade forward backpropagation neural network; MCS, minimally conscious state; SON, subject’s own name; VS/UWS, vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the subcortical electrode responses induced by different auditory stimuli in patients with DOC and explored whether these responses could improve the diagnosis of DOC. The study reveals four main findings. First, preferred music elicited more brain cortex activity than SON and familiar music in patients in VS/UWS and MCS. Second, patients in VS/UWS showed significantly decreased ApEn values in the central and medio-posterior temporal lobes compared with those in MCS in response to preferred music. Third, a resting state ApEn cut-off value of 0.77 in the prefrontal pole, based on training set data, could differentiate between VS/UWS and MCS, albeit with an accuracy rate of 61.11%. Lastly, the CFBNN model effectively extracted single-trial information from preferred music, achieving an average positive accuracy of 83.33%. This approach provides additional clinical insights for patients in a grey zone, whose consciousness state is indefinite based on behavioral evaluation.

Clinically, our study revealed that preferred music, relative to SON and familiar music, is the most effective auditory stimuli for patients with DOC. Music perception, although involving intricate processing, can potentially activate the cerebral cortex, modify cortical activity, and enhance cerebral connectivity in patients with DOC via event-related potentials33 and fMRI34. Preferred music provides familiar and personally-significant stimuli. The ‘mood and arousal hypothesis’35 and ‘autobiographical priming’ concepts have been proposed to explain music’s beneficial effects33. In the musical condition, cortical structures associated with musical perception, autobiographical memory, and consciousness showed enhanced functional connectivity in patients with DOC36. Additionally, since SON is a self-referential stimulus37 and familiar music contains memory traces38, both have been identified as effective stimuli for the arousal of patients with DOC, hence their inclusion in the current study. However, we found no significant difference between SON and familiar music stimuli when compared to the resting state. In contrast, Wu et al.39 showed that SON elicited more cortical responses than folk music; they utilized a specific music track called MOLIHUA, which lacks self-reference. Currently, significant variability exists in EEG responses to auditory stimulation in patients with DOC, influenced by cultural background, music preferences, external environment, sedation, muscle relaxants, and hearing impairment24. Therefore, in clinical practice, preferred music can be considered the optimal choice of auditory stimulation; however, it should be combined with factors such as the patient’s personal experience and cultural background.

Patients in MCS exhibited responses to preferred music in more brain area electrodes than those in VS/UWS. These findings are consistent with the notion that patients in MCS have stronger musical processing skills than those in VS/UWS. The differences in ApEn induced by preferred music were notably significant in the central, occipital, and medio-posterior temporal electrodes for patients in MCS compared with those for patients in VS/UWS; the neuroanatomical basis of consciousness may explain these observations. Conscious perception is regulated by a dynamically coordinated state of the cortical network rather than the activation of specific brain regions40,41. The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) is an important cortical network responsible for consciousness that connects the brainstem reticular structure to the cerebral cortex42. Preferred music stimulates auditory pathways through the ARAS, maintaining cortical excitability. Patients in MCS having a relatively intact neural network exhibit more pronounced cortical activity responses to preferred music43,44. VS/UWS is identified as a disconnection syndrome characterized by extensive damage in the ARAS. This condition is associated with low-level activation in primary auditory cortices without top-down feedback45.

In our cases, electrodes in the MCS patients were activated not only in the temporal lobe (auditory center) by the preferred music but also in the central electrodes. Conversely, patients in VS/UWS only exhibited activation in the prefrontal electrodes. This study speculates on the response of music to the cerebral cortex by means of subcranial electrode responses. Notably, there is no specific ‘center’ for music in the brain. Music perception relies on complex and widespread networks of cortical and subcortical regions corresponding to the basic building components of music and are distributed in both hemispheres46. Auditory signals’ journey involves travel along the ascending auditory nerve to the brainstem, especially the inferior colliculus. Subsequently, auditory information from the brainstem is transferred to the thalamus, primarily to the primary auditory cortex in the superior temporal gyrus, and directly to the limbic areas, such as the medial orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala47. Beyond the temporal cortex, the auditory network further encompasses regions in the occipital cortex, precentral and postcentral areas, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex48,49.

This study revealed the resting state ApEn value of the prefrontal pole for patients in MCS was higher than that for those in VS/UWS, and patients in both VS/UWS and MCS elicited prefrontal responses to preferred music stimuli. The lateral prefrontal cortex is associated with autobiographical memory and implicated in rhythm perception50. Thus, the resting state ApEn value of the prefrontal pole was used to distinguish between the VS/UWS and MCS. Our results revealed that the classification of VS/UWS and MCS, using a cut-off value of 0.77, achieved an accuracy of 61.11%. Sarà et al.22 conducted a 6-month follow-up evaluation using the resting state ApEn values of patients with DOC and found they exceeded 0.8. Moreover, no patients were in VS/UWS and those in MCS accounted for 22.3%; however, an ApEn value of < 0.7 was mostly observed in patients in VS/UWS. Their study does not specify an ApEn value that can distinguish VS/UWS from MCS. Consistent with our findings, the higher the ApEn value, the better the consciousness state of patient. Resting-state ApEn values could be affected by multiple factors, such as injury site and comorbidities, and the resting state does not reflect the patient’s ability to respond to external stimuli2. Hence, we speculated that relying solely on statistical calculations for the resting-state ApEn value of the prefrontal pole is an unreliable method for classifying the state of consciousness.

The neural network output is not a simple binary variable but uses a continuum of confidence values, which are then directly linked and strongly correlated to the interpretable features of EEG responses21. Therefore, EEG features, combined with ML methods, have been trained to assist in the classification of VS/UWS and MCS51. In our study, a small sample size of patients with DOC was used for the preliminary experiment, aiming to supplement the auditory stimulus-induced EEG ApEn values in an attempt to improve DOC diagnosis using the CFBNN model. As expected, this classifier showed high diagnostic performance, achieving an average accuracy of 83.33%. Porcaro et al. demonstrated that ML achieved an accuracy of 88.6% in differentiating between patients in VS, those in MCS, and healthy controls using a non-linear method called Higuchi’s fractal dimension52. The few existing studies using neural networks to classify VS/UWS and MCS are based on EEG recordings in the absence of external stimuli. These methods demonstrated remarkable performance with a high accuracy of 90.3%53. Therefore, we provide novel evidence supporting the use of preferred music-induced ApEn differences for clinical applications, especially as supplementary information to reduce misdiagnosis for patients with DOC who do not exhibit a clear behavioral characteristic.

Our study has certain limitations. First, the relatively small sample size limited the reliability of assessing the auditory stimuli’s effects. Second, the CRS-R scale was evaluated thrice on the day of EEG assessment, and clinical misdiagnosis cannot be entirely ruled out in a small number of patients in VS/UWS because of the subjectivity of the CRS-R scale. Additionally, healthy controls and atresia syndrome were not included in this study to probe the ability of the CFBNN model to discriminate between patients with MCS and healthy controls and patients with atresia syndrome, which is an important direction for future research. Finally, auditory stimuli are widely used in the study of awakening for patients with DOC because of their clinical simplicity and convenience, providing supplementary information on the patient's ability to respond to the external stimuli in the resting state. However, in cases of severe brain injury, afferent auditory impulses generated by peripheral stimuli may not reach the cerebral cortex, rendering some participants insensitive to music and consequently leading to non-reactive EEG. Therefore, a single auditory stimulus may not completely induce brain activity in patients with DOC. Future studies should incorporate a broader range of sensory stimuli and optimal multimodal sensory stimuli, tailored specifically for each patient. This approach has the potential to enhance the differentiation between VS/UWS and MCS and facilitate the arousal of patients with DOC.

Conclusions

This study provides an objective method to quantify the response of the cerebral cortex to auditory stimuli, and the simple and easily performed preferred music stimulus could be considered an arousal method for patients in VS/UWS and MCS in clinical practice. We showed, for the first time, that the resting-state ApEn values of the prefrontal pole and the preferred music-induced ApEn differences, when integrated into a CFBNN model, could enhance the diagnosis of patients with DOC. We advocate for a more systematic integration of targeted auditory stimuli into routine clinical practice. Coupled with ML algorithms, this approach holds potential for assisting arousal and improving the diagnosis of patients with DOC. Larger-scale studies are required to strengthen our conclusions and explore the application of ApEn values to diverse sensory stimuli for enhanced arousal and diagnosis of patients with DOC.

Data availability

Data supporting the results of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. This data will not be made public due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- ApEn:

-

Approximate entropy

- CFBNN:

-

Cascade forward backpropagation neural network

- CRS-R:

-

Coma recovery scale-revision

- DOC:

-

Disorder of consciousness

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- MCS:

-

Minimally conscious state

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- SON:

-

Subject’s own name

- UWS:

-

Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome

- VS:

-

Vegetative state

References

Angelakis, E. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation effects in disorders of consciousness. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 283–289 (2014).

Jain, R. & Ramakrishnan, A. G. Electrophysiological and neuroimaging studies—during resting state and sensory stimulation in disorders of consciousness: A review. Front. Neurosci. 14, 555093 (2020).

Thibaut, A., Schiff, N., Giacino, J., Laureys, S. & Gosseries, O. Therapeutic interventions in patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. Lancet Neurol. 18, 600–614 (2019).

Mertel, I. et al. Sleep in disorders of consciousness: Behavioral and polysomnographic recording. BMC Med. 18, 350 (2020).

Oh, H. & Seo, W. Sensory stimulation programme to improve recovery in comatose patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 12, 394–404 (2003).

Megha, M., Harpreet, S. & Nayeem, Z. Effect of frequency of multimodal coma stimulation on the consciousness levels of traumatic brain injury comatose patients. Brain Inj. 27, 570–577 (2013).

Särkämö, T. et al. Music listening enhances cognitive recovery and mood after middle cerebral artery stroke. Brain 131, 866–876 (2008).

Çevik, K. & Namik, E. Effect of auditory stimulation on the level of consciousness in comatose patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 50, 375–380 (2018).

Di Stefano, C., Cortesi, A., Masotti, S., Simoncini, L. & Piperno, R. Increased behavioural responsiveness with complex stimulation in VS and MCS: Preliminary results. Brain Inj. 26, 1250–1256 (2012).

Hu, Y., Yu, F., Wang, C., Yan, X. & Wang, K. Can music influence patients with disorders of consciousness? An event-related potential study. Front. Neurosci. 15, 596636 (2021).

Luauté, J. et al. Electrodermal reactivity to emotional stimuli in healthy subjects and patients with disorders of consciousness. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 61, 401–406 (2018).

Wang, F. et al. Cerebral response to subject’s own name showed high prognostic value in traumatic vegetative state. BMC Med. 13, 83 (2015).

Demertzi, A. et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity differentiates minimally conscious from unresponsive patients. Brain 138, 2619–2631 (2015).

Kondziella, D. et al. European academy of neurology guideline on the diagnosis of coma and other disorders of consciousness. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 741–756 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. The misdiagnosis of prolonged disorders of consciousness by a clinical consensus compared with repeated coma-recovery scale-revised assessment. BMC Neurol. 20, 343 (2020).

Schnakers, C. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: Clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurol. 9, 35 (2009).

Schiff, N. D. Cognitive motor dissociation following severe brain injuries. JAMA Neurol. 72, 1413–1415 (2015).

Naci, L., Sinai, L. & Owen, A. M. Detecting and interpreting conscious experiences in behaviorally non-responsive patients. NeuroImage 145, 304–313 (2017).

Claassen, J. et al. Detection of brain activation in unresponsive patients with acute brain injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2497–2505 (2019).

Liu, B. et al. Outcome prediction in unresponsive wakefulness syndrome and minimally conscious state by non-linear dynamic analysis of the EEG. Front. Neurol. 12, 510424 (2021).

Liang, Z. et al. Constructing a consciousness meter based on the combination of non-linear measurements and genetic algorithm-based support vector machine. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28, 399–408 (2020).

Sarà, M. et al. Functional isolation within the cerebral cortex in the vegetative state: A nonlinear method to predict clinical outcomes. Neurorehab. Neural Repair 25, 35–42 (2011).

Wu, D. Y. et al. Application of nonlinear dynamics analysis in assessing unconsciousness: A preliminary study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 122, 490–498 (2011).

Ling, Y. et al. Cortical responses to auditory stimulation predict the prognosis of patients with disorders of consciousness. Clin. Neurophysiol. 153, 11–20 (2023).

Engemann, D. A. et al. Robust EEG-based cross-site and cross-protocol classification of states of consciousness. Brain 141, 3179–3192 (2018).

Giacino, J. T. et al. Behavioral assessment in patients with disorders of consciousness: Gold standard or fool’s gold?. Prog. Brain Res. 177, 33–48 (2009).

Pincus, S. M. Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 2297–2301 (1991).

Bruhn, J., Röpcke, H., Rehberg, B., Bouillon, T. & Hoeft, A. Electroencephalogram approximate entropy correctly classifies the occurrence of burst suppression pattern as increasing anesthetic drug effect. Anesthesiology 93, 981–985 (2000).

Ferenets, R. et al. Comparison of entropy and complexity measures for the assessment of depth of sedation. IEEE Trans. Bio Med. Eng. 53, 1067–1077 (2006).

Jiao, S., Zhao, X. & Yao, S. Prediction of dose deposition matrix using voxel features driven machine learning approach. Br. J. Radiol. 96, 20220373 (2023).

Seo, M. W. et al. Effects of 16 weeks of resistance training on muscle quality and muscle growth factors in older adult women with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6762 (2021).

Amrhein, V., Greenland, S. & McShane, B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature 567, 305–307 (2019).

Castro, M. et al. Boosting cognition with music in patients with disorders of consciousness. Neurorehab. Neural Repair 29, 734–742 (2015).

Carrière, M. et al. An echo of consciousness: Brain function during preferred music. Brain Connect. 10, 385–395 (2020).

Nakamura, S. et al. Analysis of music-brain interaction with simultaneous measurement of regional cerebral blood flow and electroencephalogram beta rhythm in human subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 275, 222–226 (1999).

Heine, L. et al. Exploration of functional connectivity during preferred music stimulation in patients with disorders of consciousness. Front. Psychol. 6, 1704 (2015).

Cheng, L. et al. Assessment of localisation to auditory stimulation in post-comatose states: Use the patient’s own name. BMC Neurol. 13, 27 (2013).

Jagiello, R., Pomper, U., Yoneya, M., Zhao, S. & Chait, M. Rapid brain responses to familiar vs. unfamiliar music—an EEG and Pupillometry study. Sci. Rep. 9, 15570 (2019).

Wu, M. et al. Effect of acoustic stimuli in patients with disorders of consciousness: A quantitative electroencephalography study. Neural Regen. Res. 13, 1900–1906 (2018).

Melloni, L. et al. Synchronization of neural activity across cortical areas correlates with conscious perception. J. Neurosci. 27, 2858–2865 (2007).

Lamme, V. A. Towards a true neural stance on consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 494–501 (2006).

Jang, S. H., Kim, S. H. & Lee, H. D. Difference in the ascending reticular activating system injury between mild traumatic brain injury and cerebral concussion. Transl. Neurosci. 10, 99–103 (2019).

Jang, S. H. & Seo, Y. S. Ascending reticular activating system in a patient with persistent vegetative state. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, e46–e47 (2016).

Laureys, S. The neural correlate of (un)awareness: Lessons from the vegetative state. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 556–559 (2005).

Boly, M. et al. Preserved feedforward but impaired top-down processes in the vegetative state. Science 332, 858–862 (2011).

Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M. & Huotilainen, M. Music perception and cognition: development, neural basis, and rehabilitative use of music. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 4, 441–451 (2013).

Baeck, E. The neural networks of music. Eur. J. Neurol. 9, 449–456 (2002).

Maudoux, A. et al. Auditory resting-state network connectivity in tinnitus: a functional MRI study. PLOS One 7, e36222 (2012).

Demertzi, A. et al. Multiple fMRI system-level baseline connectivity is disrupted in patients with consciousness alterations. Cortex 52, 35–46 (2014).

Svoboda, E., McKinnon, M. C. & Levine, B. The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia 44, 2189–2208 (2006).

Höller, Y. et al. Comparison of EEG-features and classification methods for motor imagery in patients with disorders of consciousness. PLOS One 8, e80479 (2013).

Porcaro, C. et al. Fractal dimension feature as a signature of severity in disorders of consciousness: An EEG study. Int. J. Neural Syst. 32, 2250031 (2022).

Altıntop, Ç. G., Latifoğlu, F., Akın, A. K., Bayram, A. & Çiftçi, M. Classification of depth of coma using complexity measures and nonlinear features of electroencephalogram signals. Int. J. Neural Syst. 32, 2250018 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study thank all the staff who supported this research from rehabilitation department of Second Hospital of Shandong University. We thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions helped improve this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D program Projects of China (2020YFC2006100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Fanshuo Zeng, Sheng Qu, Xinchun Wu. Data curation: Sheng Qu, Yaxiu Tang, Qi Zhang. Funding acquisition: Fanshuo Zeng. Methodology: Sheng Qu, Xinchun Wu, Shengxiu Jiao, Qiangsan Sun. Writing – original draft: Sheng Qu, Laigang Huang, Xinchun Wu. Writing – review & editing: Fanshuo Zeng, Baojuan Cui, Qiangsan Sun. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, S., Wu, X., Tang, Y. et al. Analyzing brain-activation responses to auditory stimuli improves the diagnosis of a disorder of consciousness by non-linear dynamic analysis of the EEG. Sci Rep 14, 17446 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67825-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67825-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Functional connectivity in whole-brain and network analysis differentiates minimally conscious from unresponsive patients: a resting-state fNIRS study

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)