Abstract

We report time resolved observations of the crystallization from liquid hydrogen, supercooled to temperatures below the melting point, using 11.2 keV X-ray diffraction from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). Changes to the metastable solid and liquid structure factors have been dynamically measured. This allows for a direct determination of the lowest energy crystal polymorphs, the stacking probabilities, as well as the liquid and solid densities and temperatures. Such measurements provide experimental evidence of an Arrhenius-like growth kinetics along the stacking direction during supercooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The free energy pathway of supercooled liquids, leading to nucleation and growth of metastable structures, is a vastly underexplored phenomenon in condensed matter physics where the theoretical framework relies almost exclusively on computational methods that incorporate elements of classical nucleation theory (CNT)1,2,3,4,5. While CNT provides a useful model for understanding nucleation and growth at the microscopic level, a comprehensive understanding of crystal growth is far from complete. Many theories are untested because of the Ångström length scales involved, which are exceptionally challenging to dynamically probe3. Phenomena such as the kinetic pathways describing the initial and final structures of polymorphs6,7, the crystal growth rates and anisotropies4,5,8,9, as well as the local order across the liquid-to-solid transition10 remain a focus of debate with no conclusive experiment or theory. Accessing in situ details of the crystallization process at the atomic level becomes paramount towards understanding the minimum energy structures of the system. Ultrafast X-ray diffraction with high peak brightness11 is an effective method to resolve correlations on Ångström length scales12. This results in access to the structure factors of hydrogen at the temperatures of both the solid and liquid phases. In addition, crystal stacking and crystal growth rates can be resolved during supercooling.

Anisotropic lattice growth velocities as a result of supercooling have been well documented by both simulations and experiments13,14. Supercooled Lennard-Jones (LJ) liquids have been shown to crystalize into the face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice from initial polymorphs of random hexagonal close-packed (rhcp) structures9,15. Early molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggest growth kinetics of the cubic (111) face resemble a Wilson-Frenkel (WF) like behavior where the step responsible for activation is not the simple diffusion, but rather the coordinated motion of atoms at the interface selecting either all fcc or all hcp lattice sites before a new layer can grow5. Such a process requires significant time to reach the local potential energy minimum resulting in a slower growth rate. The cubic (100) face, on the other hand, has no such restrictions and will follow a barrier-less collisional growth that is orders of magnitude faster resulting in a clear growth rate anisotropy between the two lattice faces. However, recently measured crystallization rates in supercooled argon and krypton binary mixtures coupled with MD simulations suggest a modified collisional model is responsible for the slower (111) growth relative to the (100), both of which resemble barrier-less collisional growth9.

Supercooled molecular hydrogen, in contrast to other LJ systems, has demonstrated a clear preference for hexagonal close-packed (hcp) nucleation as opposed to fcc nucleation from an initial polymorph of rhcp structures16,17,18,19. The single stacking direction in hcp crystals excludes a stacking in another direction, consequently, a non-integral step on a closed-packed surface is not possible. Therefore the hexagonal symmetry of the hcp lattice only allows a single stacking direction along the (111) cubic axis and is primarily orthogonal to the liquid-to-solid diffusion direction. Such degeneracy allows for a unique platform to study the diffusion of crystal growth along the (111) plane in a supercooled LJ-like system. To date, such measurements have primarily relied on MD simulations to evaluate both the crystal growth rates and the stacking direction. Our data directly show, without the need for MD simulations, that the growth kinetics for the cubic (111) face (i.e. the hexagonal c-axis (0001)) in hydrogen are best described using the WF like diffusion model proposed by Burke et al5.

Here, we report a comprehensive analysis of stacking fault dynamics and crystal growth rates from supercooled liquid hydrogen with \(\mu \)s time resolution. We observe that the crystal nucleation kinetically favors the lower energy ordered hcp lattice during solidification from an initial polymorph consisting of rhcp with regions of fcc-like microstructures. Our experimental data show that the probability of finding an hcp stacking sequence increases continuously during solidification. This result indicates that structural ordering occurs with a kinetic pathway towards the hcp structure as functions of crystal growth time and temperature where the crystal growth, along the stacking direction, follows an Arrhenius-like dependence on temperature.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction

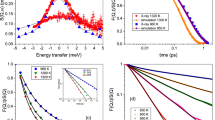

(a) Scattering measurements normalized to the Compton background (black) with fit to the data (red-blue). The color of each fit corresponds to the measured solid fraction of the microject where red is liquid and blue is solid. Shaded regions correspond to the stacked hcp-like, \(\beta _{22}\), (blue) and fcc-like, \(\beta _{44}\), (orange) structures. (Inset)—Measured solid structure factor with fit (blue) at t=19.83 \(\mu \)s with the q-dependent background removed and rescaled to show low intensity diffraction signals. (b) Wavenumber dependent intensity deconvolution of all identified \(H_{2}\) scattering contributions at a fixed time of \(t=\)3.5 \(\mu \)s from the nozzle. (c) Temperature as a function of the density20,21,22 calculated for supercooled metastable liquid hydrogen. Solid line (red) is the least squares fit to the reported values and used to extract the liquid temperatures.

Figure 1a shows at early times from the initial \(H_{2}\) liquid injection, the diffraction profiles exhibit a broad diffuse peak characteristic of the liquid state. With increasing time, a reduction in the liquid scattering accompanied by the rise in intensity of twelve identified peaks from hcp and fcc solid structures become the dominant scattering contributions. Figure 1a inset shows the measured low intensity azimuthally integrated powder pattern of the solid structure factor at complete solidification. Stacking disorder in single crystals leads to rod-like features in reciprocal space that are aligned along the disorder axis and are observed as lines, or streaks, in the measured diffraction pattern for a single scattering event. The orientationally averaged diffraction pattern, from multiple scattering events, thus emerges as a broadened diffraction peak centered around the hcp \(\{10l\}\) indices. The identified hcp peaks associated with stacking disorder continuously narrow and increase in intensity as a function of time characteristic of a lattice with increasing proportion of narrowly spaced intrinsic stacking faults. The deconvolution of all identified \(H_{2}\) scattering contributions at a fixed time of t=3.5 \(\mu \)s from the nozzle are observed in Fig. 1b. These contributions include the Compton scatter modeled using impulse approximation23,24, the thermal diffuse scatter (TDS) directly calculated using the wavenumber dependency of the Bragg peak intensity25, the liquid structure factor, and the solid structure factor fitted using a modified stacking disorder algorithm in combination with the DIFFaX26 open source software. Here, TDS is calculated from the wavenumber dependent Bragg peak intensity with the analytical form \(S(k)=f(k)(1-e^{-k^{2}\langle x^{2}\rangle })\).

The liquid structure factor was inferred from the best fit using previously reported quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations of metastable liquid hydrogen20. We directly measured the density of the liquid by the position of the first correlation peak, and calculated the densities of the solid formations using the best-fit to the diffraction peak positions modeled with DIFFaX. Increasing the density of the liquid, the main peak position moves higher in q corresponding to shorter interparticle distances. Using the relationship observed in Osychenko et al.20 we can infer the same density correlation by accurately measuring the peak position of the liquid static structure factor, \(S_{ii}\). Additionally, we can directly calculate the density of the solid by observing and modeling the shift of the twelve identified solid diffraction peak positions. The relationship between \(q_{max}\) and the liquid density is observed in Fig. 2. As a consequence of using a low bandwidth X-ray Free Electron Laser source, the exact q positions of the liquid and solid structure factors can be precisely measured. Moreover, by modeling twelve solid diffraction peaks the solid density can accurately be measured to within ±1x\(10^{-3}\) \(g/cm^{3}\). The direct relationship between density and temperature (Fig. 1c) was utilized to calculate the total energy exchange of the system. The temperature loss via evaporative cooling was approximately \(\Delta T \sim \) 4.5 K, starting from an initial liquid cryostat temperature of \(T \sim \) 17 K (\(\rho = 0.0226\) Å\(^{-3}\)). A final temperature of \(T \sim \) 12.5 K (\(\rho = 0.0236\) Å\(^{-3}\)) was achieved near a temperature below the freezing temperature (T = 13.9 K), where the liquid phase should be unstable, but above the estimated superfluid transition temperature.

Microstructures

Schematic showing the evolution of the stacking sequences and the subsequent microstructures that are modeled in this study. Here a stacking fault (SF) following pathway 1, will result in either a \(\beta _{22}\) hcp-like microstructure that will grow over time, or a single isolated intrinsic stacking fault (ISF); A stacking sequence following pathway 2, will likewise result in an isolated extrinsic stacking fault (ESF), or a microtwin that can grow, \(\beta _{44}\). Each structure is dictated by its probability \(\alpha _{ij}\) and the previous stacking sequence. The dashed lines represent the planer or interplaner location of the stacking fault. \(^{*}\) Isolated ISF or ESF embedded in the regular fcc stacking sequence. Purple regions show the growth of the two possible microstructures tested in this analysis.

Due to the small energy difference between the fcc and hcp structure \((1-E_{fcc}/E_{hcp})\) \(\sim \)1x\(10^{-5}\), crystal layers in hydrogen have a strong tendency towards random stacking and interplaner disorder16,17,18. Here we show that supercooled liquid hydrogen will initially crystallize into an rhcp structure from which hcp stacking statistically dominates the crystal growth at later times. The rhcp structure is best described as a sequence of hexagonal planes with equal probabilities to adopt either an fcc or an hcp structure via interplaner shifts between a series of atomic layers. This shift implies that each atomic plane occupies one of three distinct lateral positions (A, B, or C). For example, the structures illustrated in Fig. 3 consist of layers along the hexagonal c-axis, which are stacked with a lateral shift of one-third of the lattice parameter in the periodic ABA (hcp) or ABC (fcc) sequences. The stacking disorder is described by the probability, \(\alpha \), of finding an hcp stacking sequence among three randomly chosen layers. Consequently, 1-\(\alpha \) is the probability of observing an fcc stacking sequence. Thus, a perfect fcc crystal (\(\alpha \)=0) has a sequence ABCABC of hexagonal planes along the (111) direction and a perfect hcp crystal (\(\alpha \)=1) has a sequence ABABAB of atomic planes along the hexagonal c-axis. The statistical averaging over a pure rhcp crystal leads to the observation of both fcc and hcp structures with equal probability (\(\alpha \)=0.5). Microstructures, reported in Table 1, can be responsible for deviations in the regular fcc stacking sequence27,28. Each structure, and formation pathway, is illustrated in Fig. 3. Specifically \(\beta _{44}\) indicates the growth extant of twins caused by stacking faults (SF) located between two consecutive (111) planes, and \(\beta _{22}\) is the growth extant of narrowly spaced intrinsic stacking faults (ISF) that are arranged next to each other on every second (111) lattice plane (i.e. both \(\alpha _{12}\) and \(\alpha _{22}\) are nonzero). Likewise, isolated extrinsic stacking faults (ESF) are a limit of very thin twins (\(\alpha _{44}=0\)). Each pathway will result in a unique set of stacking sequences that affect the observed diffraction profile, shown in 4.

Figure 4 shows the differences such sequences have on the generated diffraction signal. A faulted fcc crystal composed of one in ten stacking sequences with an ISF will decrease and asymmetrically broaden the (111) peak to higher wavenumbers as well as decrease and shift the (200) to lower wavenumbers with respect to a perfect fcc lattice. A faulted crystal with one in ten sequences with an ESF will conversely decrease and asymmetrically broaden the (111) peak to lower wavenumbers as well as shift the (200) to higher wavenumbers with respect to a perfect fcc lattice. A faulted fcc lattice composed of one in twenty twins on the other hand will result in a lower average diffraction intensity, an increase in the profile width, and no observed shifts in the (111) or (200) diffraction peaks. Our data show that pathway 1, identified in Fig. 3, will result a diffraction pattern that is consistent with our measurements.

Influence of microstructures on the observed powder diffraction profile simulated with DIFFaX. (left) X-ray diffraction pattern generated with, (black) an un-faulted fcc lattice, (red) 0.10 intrinsic stacking faults, (blue) 0.10 extrinsic stacking faults, (dashed purple) 0.05 twinned structures28. (right) Diffraction profiles generated with increasing portion of narrowly spaced stacking faults given by the probabilities \(\alpha _{22}\) = 0.00, 0.10, 0.33, 0.66, and 0.90 with a constant \(\alpha _{12}\) = 0.05 probability of isolated ISFs.

Figure 5b shows exact finite probability values of \(\alpha \) cannot be used to model the observed diffraction data. Therefore, the measured diffraction signals are likely explained by some unique combination of stacking probabilities. We denote the cumulative set of stacking probabilities (each representative of a single continuous probability density function) as a probability distribution function (PDF). The measured diffraction patterns in this study can be fitted and determined using DIFFaX where the stacking PDFs are determined using a biased random walk and constrained with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling method. In our analysis we can assign a single stacking parameter distribution to a probability density function where the parameter \(\bar{\alpha }\) is the mean expectation value of the distribution, while the parameter \(\sigma \) is the standard deviation. Here a single distribution describes all possible outcomes of a random process (i.e. the integral over the distribution is equal to 1).

To fit the data shown in Fig. 5c from a very basic model of interplanar lattice shifts using DIFFaX, we use a MCMC sampling method to determine the most probable posterior PDF from which we can then compare to a biased random walk. Here MCMC is used as a method that repeatedly generates random values of \(\alpha \) for the parameters of a distribution based on the current values of \(\alpha \). If the random values are in agreement with the data, the values are assigned to the parameters and become the current solution. The generated values are rejected or accepted on the basis of fit error minimization. We can use the average of these values as the most likely initial and final distributions from which to construct a PDF made up of individual discrete Gaussian distributions. For example, Fig. 5a shows the most likely initial and final discrete distributions (binned) generated randomly from sampling \(\alpha \) from which it is possible to then compare to a bias random walk in a 2D \(\bar{\alpha }\) and \(\sigma \) phase space. The continuous profiles (dashed lines) plotted in Fig. 5a show the actual distributions determined by the biased random walk. The solid lines correspond to the individual continuous probability density functions that represent the final PDF when summed.

(a) MCMC distribution generated from random sampling \(\alpha \) values fit to solid diffraction data for \(t=2.8\) \(\mu \)s (dark blue) and \(t=19.8\) \(\mu \)s (light blue). Full continuous distribution (lines) of hcp growth generated with the MCMC + random walk simulation for \(t=2.0\) \(\mu \)s (orange), and \(t=19.8\) \(\mu \)s (magenta). (b) Background subtracted solid diffraction data for \(t=2.0\) \(\mu \)s (dark blue) and \(t=19.8\) \(\mu \)s (light blue) plotted together with generated diffraction profiles corresponding to finite stacking parameter probabilities with no variance. The color of each line corresponds to the specific mean stacking parameter probability represented by the squares in (a) of the same color. (c) Background subtracted solid diffraction data for \(t=2.0\) \(\mu \)s (dark blue) and \(t=19.8\) \(\mu \)s (light blue) plotted together with the PDFs shown in (a).

Crystal growth rate

The stacking parameter PDFs plotted in Fig. 6 demonstrate gradual structural changes of the rhcp crystals towards the lower entropy and slightly more energetically favorable hcp lattice from the initial rhcp polymorph as a function of time, thus leading to a continuous spectrum of the stacking probability, \(\alpha \), produced from each new layer that forms. The measured diffraction data at each specified time are not indicative of a new crystal that grows instantaneously, but rather the statistical average of crystal growth starting from \(t=0\). At times below 3.5 \(\mu s\), where the coldest parts of the microjet solidify rapidly and layers are easily trapped in a metastable state, the relative ratio of new hcp layers to fcc layers and subsequently the hcp stacking probability is almost entirely random (\(\alpha \) \(\sim \)0.45) . Beyond t=3.5 \(\mu s\) the probability of ISFs, \(\alpha _{12}\), remains constant where the growth of the sub-structure is proportional to the layered hcp growth, \(\alpha _{22}\).

(Top)—The total stacking parameter distribution (dashed lines) plotted for t=\(0 - 3.5\) \(\mu \)s, t=\(0 - 12\) \(\mu \)s, and t=\(0 - 25\) \(\mu \)s, summed over individual discrete gaussian distributions (solid lines) with a specific mean (\(\bar{\alpha }\)) and variance (\(\sigma \)) modeled with N=4, N=19, and N=25 crystal layers respectively. As time increases the discrete probability density function mean (\(\bar{\alpha }\)) shifts towards an hcp stacking sequence and the variance (\(\sigma \)) decreases . (Bottom)—Total stacking probability distribution function (PDF) fitted to the scattered data as a function of time.

Applying our analysis to the measured diffraction data, we can model each consecutive layer that forms during crystal growth where the rhcp lattice statistically favors the lower energy hcp crystal until full solidification is achieved at a mean stacking probability approaching \(\alpha \) \(\sim \)0.80. Over this time duration, the crystal experiences a transformation to the more stable hcp structure continuously. Yet, because there is a small energy barrier separating the two lattice types, the selection of stacking can be probabilistic and modeled using a biased random walk. The results from Fig. 6 show that every layer that grows during crystallization as a function of time has an increased mean stacking probability, as well as a reduced probability distribution that form in the lattice along the hexagonal c-axis (or fcc (111) plane). The error bars plotted in Fig. 6 incorporate the effect of texture on the inferred mean stacking probability, due to the preferred orientation of crystal formation along the hexagonal c-axis (initiated via the crystal-liquid thermal gradient) resulting in changes to the relative ratio of diffraction intensities in the measured azimuthal direction.

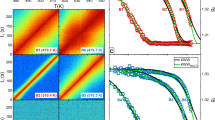

The time evolution of the liquid/solid fraction in the scattering volume is deconvolved and extracted from the measured diffraction data (Fig. 1). Moreover, as the microjet cools, the density of both the liquid and solid structures increases resulting in a measurable change of the lattice constants and the corresponding temperatures of the systems (Fig. 7). At \(t=0\), when the liquid hydrogen is injected into the vacuum, the outside surface experiences the largest temperature gradient resulting in a faster transfer of heat than the interior. Hence, a temperature gradient across the microjet radius is established as soon as its surface is exposed to vacuum. The outer layer begins to crystallize as soon as the temperature reaches the freezing point. Due to the rapid loss of heat from the initial cooling, the liquid interior continues to cool to temperatures below the melting point while crystallization growth from the crystal-liquid interface persists (Fig. 7). The rate of cooling agrees well with numerical calculations based on Knudsen’s model of evaporative cooling. Here, the calculated results are comparable to the mean cooling observed in Kuhnel et al.18 using a 5 \(\mu m\) diameter microjet. The inner region of the microjet is the largest contributer to the solid diffraction, and is also the region where the crystal-liquid interface is observable. Our results show evidence that the crystal layers formed can grow by having atoms at the interface move onto sites consistent with their respective sub-lattice, possibly as a result of the latent heat transfer. For a layer to grow, it must completely anneal itself to either all fcc sites or all hcp sites during crystallization thus requiring some form of activation energy5. Such annealing would slow growth for the (111) relative to the (100). We show there is no predictive assurance that a site will select one stacking preference over another as it can be nearly random. However, our analysis shows a preference towards the hcp lattice for each new layer that forms.

(left)—Inferred average temperature of the microjet solid (red circles) and liquid (green circles) as a function of time. The solid fraction (blue circles) is overlaid in the plot, and fitted (blue line) using an Avrami rate equation2 of the form C(t)=\(1-e^{-k(t-\tau )^{n}}\), where k=0.33 \(s^{-1}\) and n=1.9. The lines overlaid show numerical calculations based on Knudsen’s model of evaporative cooling for the central (green), inner (orange), and outer (purple) region of a 10 \(\mu m\) diameter microject. The orange dashed line represents the average inner temperature calculated with a 5 \(\mu m\) diameter microjet as a comparison to Kuhnel et al.18 (right)—Semi-log of the crystal growth velocities applying \(D_{WF}(T)\) (red shaded region), and \(D_{CL}(T)\) (blue shaded region) diffusion models to Eq. 1 compared to the experimental data (white circles). Each curve plotted represents the best fit to the data varying the the geometric factor \(f_{0}\) where \(f_{0}=2/3\), \(f_{0}=1/3\), and \(f_{0}=1/6\) (dotted, solid, and dashed lines). The two models are extrapolated from the free energy difference between the liquid and solid16,29 and previously reported values of the self-diffusion coefficient30,31.

It is known from similar microjet studies that nucleation events are distributed homogeneously and only on the surface (lowest vapor pressure), so that the liquid-solid-interface propagates towards the core isotropically along the radial direction18,32. This model is supported by fitting the solid fraction curve with the Avrami equation (Fig. 7), which yields an exponent n=1.9, indicative of nucleation embryos with n=2 growth dimension. In our study the finite size of the crystal can be modeled using DiFFaX and fitted to the solid diffraction profile. Simulating a crystal growth along the (111) plane we can approximate the velocity growth of each stacking layer per time per temperature as long as the full crystal can be sub-divided into the unique basis layers shown in Fig. 6. In our analysis, N represents the number of sequential layers modeled for a unique series of stacking arrangements. Any finite thickness, as long as it possesses the same sequence of N layers will result in the same diffraction pattern. The modeled growth velocity per measured temperature is plotted in Fig. 7. The growth direction is only along the (111) plane and in the direction of the thermal gradient, as previously discussed. Here our measurements are constrained to 2-D slices of the microjet because the mean crystal growth velocity is much smaller than the mean microjet velocity (\(\bar{u}\)=100 m/s), effectively removing one direction in view of crystal growth, consistent with Avrami n=1.9 exponent. Using the solidification time calculated from Fig. 7 for a known microjet diameter, along with the measured relative change in the number of N stacking layers observed in Fig. 6, it is possible to directly infer the crystal growth rates of the system along the (111) lattice plane.

The steady-state crystal growth rate is typically expressed by2:

where \(k_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant, \(\Delta S_{m}\) is the entropy difference and \(\Delta G(T)\) is the Gibbs free energy difference between the liquid and the crystal, \(f_{0}\) represents the fraction of collisions with the crystal surface resulting in crystallization, and a(T) is the lattice parameter describing the intermolecular spacing. The atomic diffusivity, D(T), can either be characterized by a collisional model given by \(D_{CL}(T)\) or expressed by an Arrhenius model governed by \(D_{WF}(T)\). In the collisional model \(D_{CL}(T)\)=\((1/\Lambda (T))\sqrt{3kT/m}\), where m is the particle mass and \(\Lambda (T)\)=ca(T) is the atomic displacement with c being a dimensionless parameter. Here the crystallization is proportional to the particle thermal velocity where a Boltzmann distribution governs collisions at the liquid-crystal interface4 and the step responsible for activation is barrier-less. Alternatively the atomic diffusivity can be understood by a thermally activated crystal growth first proposed by Wilson-Frenkel (WF)8 where the diffusion follows an Arrhenius-like dependence on temperature given by \(D_{WF}(T)\)=\((D_{0}/\Lambda (T)^{2})e^{-E_{D}/T}\), where \(D_{0}\) is the liquid self-diffusion coefficient, and \(E_{D}\)=E/k is the activation energy.

Two different mechanisms for crystal growth are modeled using either collisional (\(D_{CL}(T)\)) or Arrhenius-like (\(D_{WF}(T)\)) diffusion. The data plotted in Fig. 7 is described using a crystal growth rate that is proportional to the atomic diffusivity where the best results is achieved with an activation energy of \(E_{D}\)=45 K and a geometric factor between \(f_0=0.166\) and \(f_0=0.666\). This growth has been directly inferred without the use of MD simulations, and demonstrates the utility of dynamically measuring such environments using X-ray pulses. Since the microjet flow velocity is constant (with some measurement error), the observed stacking parameter distribution variance cannot be fully explained as a measurement error but rather a result of growth rate reduction. Fast crystal growth rates result in a broader distribution of layer growth and individual stacking probabilities for a given measurement. As the growth slows, the distribution reduces to a finite value that corresponds to the intrinsic measurement error of the microjet flow velocity. Such an observation is consistent with an Arrhenius-like growth behavior where the rate is high at earlier times during crystallization and lower as the liquid approaches full solidification (i.e. later times, lower temperatures).

Conclusions

In summary, we have observed the crystallization dynamics of supercooled liquid hydrogen, where both hcp and fcc solid phases have been identified and attributed to the presence of stacking faults. The high-resolution X-ray diffraction data show that the crystals have a continuous spectrum of stacking probabilities with an initial random stacking probability of \(\alpha \)=\(0.45 \pm 0.05\) in rhcp crystals whereby layers that grow during crystallization favor an hcp lattice. Such layers are modeled statistically where the transition from the metastable rhcp to a more stable hcp-like structure during solidification occurs continuously. Moreover, we have reported the dynamic behavior of both liquid and solid structure factors of supercooled hydrogen as well as the ability to infer both the temperature and density of the metastable liquids and solids, where the crystal growth rate is proportional to an Arrhenius-like diffusion along the stacking direction.

Methods

Experimental setup

Schematic of the experimental setup showing 11.2 keV LCLS X-ray beam scattering from a supercooled \(H_{2}\) microjet. The scattered photons are captured on a detector to angularly resolve the solid and liquid structure factors as a function of distance from the nozzle. A photodiode is placed in the backscatter geometry to measure the incoherent Compton background, and a fiber-delayed dual pulse optical laser, with a fixed 500 ns delay, is used to measure the microjet velocity, per scattering event, by the superposition of crystallites imaged on an OPAL camera. (Top) A visualization of the stacking sequence measured via the changes to the diffraction peaks as a function of time from the nozzle. (Bottom) Raw scattering data as a function of position from the nozzle, in counts, accumulated for \(\sim \)10 minute increments collected at 120 Hz pulse repetition rate. Single exposure inset shows diffraction from stacking faults (lines), and crystals (spots). The liquid to solid scattering ratio is large at a distance of 300 \(\mu \)m and decreases farther away from the nozzle.

The experimental configuration is shown in Fig. 8. Here, supercooled liquid hydrogen was produced by injecting pressurized normal-\(H_{2}\) liquid, initially cooled to a temperature of \(\sim \)17 K, through a 10 \(\mu \)m diameter capillary orifice into a high-vacuum chamber. The liquid emerges as a continuously flowing cylindrical filament that rapidly cools by surface evaporation as a function of distance from the nozzle18,32,33,34.

To measure the structure of the solid/liquid hydrogen microjet, we used 11.2 keV X-ray pulses from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) focused to a 10 \(\mu \)m spot using beryllium compound refractive lenses resulting in a photon flux of \(\sim 10^{11}\) photons per pulse incident on the \(H_{2}\) microjet. It is worth noting that hydrogen is transparent to 11.2 keV X-rays (\(I/I_{0}=0.9999\)), therefore absorption heating has no effect on the temperature measurements. The diffracted signals were recorded with Cornell SLAC Pixel Array Detectors (CSPAD)35 placed at scattering angles between \(2\theta \)=2.5\(^{\circ }\) and \(2\theta \)=50\(^{\circ }\) in order to fully resolve the structure factors of rapidly cooling hydrogen.

Increasing the distance between the cryostat nozzle and the X-ray focus, along the microjet axis, (Fig. 8), allows for the measurement of the crystallization kinetics. The velocity of the microjet was monitored using two 800 nm optical laser pulses fiber delayed by 500 ns that were temporally synchronized to the X-ray laser pulses and imaged with an OPAL detector33. Such a dual pulse image setup can directly capture unique micro-structural features that periodically occur near, or inside, the microject. A jet velocity can be determined by measuring the distance such features move in 500 ns for every shot when a defect occurs, as shown in Fig. 8. Thus, for a fixed distance \(\Delta \)z away from the nozzle, an absolute time measurement corresponding to each scattering event could be calculated. Composite diffraction patterns constructed from approximately 60,000 events for each z-position were used to analyze the liquid and solid structures. Additionally an X-ray photodiode placed in the backscatter geometry was used to monitor the Compton background generated from each X-ray pulse interaction with the hydrogen microjet in order to normalize the collected scattered X-ray intensity and properly account for X-ray beam and microjet overlap.

Evaporative cooling model

The evaporation rate of the hydrogen micro-jet is calculated using Knudsen’s theory of evaporation, and based on the thermodynamic properties of the liquid. The temperature change rate of a volume of liquid subject to evaporative cooling is proportional to the evaporation rate given by:

and proportional to the temperature change caused by a single evaporation event. Thus the temperature change rate of the volume is given by

where T(t) is the temperature dependent time of evaporation, \(P_{\text {sat}}(T)\) is the saturation vapor pressure, m is the mass of the evaporating molecules, \(k_{B}\) is Boltzmann’s constant, \(A(R)=2 \pi R_{max}\) is the 2D surface area of the evaporating volume where \(R_{max}=\)10 \(\mu m\), \(\rho (T)\) is the time dependent density, \(\Delta L_{\text {evap}}(T)\) is the latent heat of vaporization per molecule, \(\Delta V(t)\) is the volume from which evaporation takes place, and \(C_{P}(T)\) is the isobaric specific heat capacity. For each time step in the numerical calculation, the heat flux within the micro-jet is computed. The filament geometry is modeled as a cylinder divided into \(n_{max}\) layers of uniform thickness \(\Delta r\), indexed n, where n decreases with decreasing cylinder radii \(r_{n}\). Using equation 3, \(\Delta V(t)\) and T(t) represent the volume and temperature of the outermost layer. The heat flow dQ/dt through the surface between the \(n_{th}\) and \((n+1)_{th}\) layer inside the filament is calculated using Fourier’s law of thermal conduction:

where \(\lambda (T)\) is the thermal conductivity, \(r_{n}\) is the radius of the filament dividing the integer layers/rings, and \(T_{n+1}-T_{n}\) is the temperature difference between layers. An energy balance is set up for each layer and the temperature change \(\Delta T_{n}\) for the \(n_{th}\) layer is then calculated as:

Here \(\Delta Q_{n}\) is the net heat exchange between layers. The temperature of the surface layer \(T_{n}\) is numerically approximated using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method. Subsequently, the temperature exchange \(\Delta T_{n}\) is calculated and added/subtracted to/from the two participating layers in a consecutive manner towards the center of the filament. All values are summarized in Table 2. The specific heat capacity, the thermal conductivity, and the saturated vapor pressure are extrapolated values with empirical equations to match the available reported values above and below the melting temperature36,37,38,39,40,41.

Biased random walk

In order to quantitatively infer the crystal structure and growth as a result of stacking disorder during the solidification of hydrogen, we use the open source DIFFaX computer program for calculating the powder diffraction patterns of crystals containing specified stacking sequences. DIFFaX uses a general recursion algorithm along with information about the structure of the layers, the symmetry relationships between the stacked layers, and the stacking probabilities \(\alpha \) to construct a diffraction pattern26. The calculated diffraction pattern is convolved with a profile function in order to account for finite crystallite size and instrument broadening effects.

Measured background subtracted x-ray diffraction of \(H_{2}\) at the start of crystallization (top) and full solidification (bottom). Generated x-ray profiles using DIFFaX are plotted with the data for each cumulative stacking probability distribution function (PDF) constructed from individual probability density functions corresponding to \(\bar{\alpha }\), \(\sigma \), and the relative number of crystallites. (right)—A biased random walk simulation is used to model each layer of crystal growth using a Normal distribution with mean drift bias of \(\Gamma =0.00\) (unbiased), \(\Gamma =0.5\) (quasi-biased), and \(\Gamma =5.0\) (strong bias) of crystal growth layers towards increased hcp stacking parameter from an initial single gaussian distribution. Contours overlaid (lower right figure) indicate the time history of earlier \(\bar{\alpha }\), \(\sigma \) values. Gray bands (upper left figure) indicate diffraction signals that are attributed to the microjet nozzle observed at measurements for t < 3.5 \(\mu \)s).

The bias walk starts with a single stacking parameter distribution randomly generated within the most probable range of values 0.23 < \(\sigma \) < 0.28, and 0.40 < \(\bar{\alpha }\) < 0.50. This range is empirically pre-determined using the MCMC algorithm to obtain the most likely phase space from which a distribution adequately approximates the earliest measured PDF. The distributions are subsequently modified by taking N number of randomly generated step sizes (\(\sigma \) and \(\bar{\alpha }\)) for some biased drift towards the most probable“late time”PDF within a range of values corresponding to 0.70 < \(\bar{\alpha }\) < 0.80 for a \(\sigma \) approaching .01, again pre-determined via the MCMC method. This process is repeated with at least 100 iterations, and the solid structure is plotted as a sum of all the steps and iterations. There exists only two independent fitting parameters to achieve the best fit to the data, the number of steps (N) and the random walk drift bias (\(\Gamma \)), where \(\Gamma \) is biasing steps for both \(\sigma \) and \(\bar{\alpha }\).

The drift bias range and number of steps for each diffraction data time series was determined by least squares fitting. To determine the conditions from the measured diffraction, we apply an error reduction analysis using \(\chi ^{2}\) minimization over a wide range of N steps and drift bias (\(\Gamma \)) for a fixed number of random walk simulations (\(N_{S}\)=100). The best fit is defined by minimizing the mean square deviation between data and model, \(\chi ^{2}\), whereas the quality and robustness of the fit is estimated by the values of \(\chi ^{2}\) that deviate beyond a 2\(\sigma \) variance over the entire diffraction data. The generated solid structure factor fit to the measured diffraction data is shown in Fig. 9 for time measurements of t=2.8 \(\mu \)s and 19.8 \(\mu \)s. Here the solid polymorph is plotted for the best fit N steps (layers) for a bias of \(\Gamma =0.00\), \(\Gamma =0.5\), and \(\Gamma =5.0\), as well as N+/-1 layers for a bias of \(\Gamma =5.0\). The 2D \(\bar{\alpha }\) and \(\sigma \) phase plots on the right hand side correspond to the cumulative number of unique crystals modeled using the specified individual probability density functions with values of (\(\bar{\alpha }\) and \(\sigma \)). Each individual gaussian distribution of \(\bar{\alpha }\) and \(\sigma \) is representative of one pixel (\(\sigma (.01)\) x \(\bar{\alpha }(.01)\)) on Fig. 9. The best fit to the data as a result of \(\chi ^{2}\) minimization correspond to a bias of \(\Gamma =5.0\) and a crystal growth that correlates with probing time. The data consistently show crystal growth as a function of probing time where each measured diffraction spectra can be fully interpreted as a crystal polymorph with a higher probability of new hcp layer(s) forming per growth layer per probing time. This is highlighted by the contours, for each subsequent time measurement, plotted in Fig. 9.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kelton, K. F. & Greer, A. L. Nucleation in Condensed Matter (Elsevier, 2010).

Jackson, K. A. Kinetic Processes (Wiley, 2004).

Sosso, G. C. et al. Crystal nucleation in liquids: Open questions and future challenges in molecular dynamics simulations. Chem. Rev. 116, 7078–7116. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00744 (2016).

Broughton, J. Q., Gilmer, G. H. & Jackson, K. A. Crystallization rates of a lennard-jones liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1496–1500. https://doi.org/10.1103/49.1496 (1982).

Burke, E., Broughton, J. Q. & Gilmer, G. H. Crystallization of fcc (111) and (100) crystal-melt interfaces: A comparison by molecular dynamics for the lennard-jones system. J. Chem. Phys. 89, 1030–1041. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.455254 (1988).

Peng, T., Xu, N. & Xu, L. Visualizing kinetic pathways of homogeneous nucleation in colloidal crystallization. Nat. Phys. 10, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2817 (2013).

Oxtoby, D. W. New perspectives on freezing and melting. Nature 347, 725–730. https://doi.org/10.1038/347725a0 (1990).

Frenkel, Y. The Kinetic Theory of Liquids. (Oxford University Press, 1946).

Schottelius, A. et al. Crystal growth rates in supercooled atomic liquid mixtures. Nat. Mater. 19, 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0613-z (2020).

Sun, G., Xu, J. & Harrowell, P. The mechanism of the ultrafast crystal growth of pure metals from their melts. Nat. Mater. 17, 881–886. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-018-0174-6 (2018).

Emma, P. et al. First lasing and operation of an ångstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photonics 4, 641–647. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.176 (2010).

Fletcher, L. B. et al. Ultrabright x-ray laser scattering for dynamic warm dense matter physics. Nat. Photonics 9, 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2015.41 (2015).

Uyeda, R. The morphology of fine metal crystallites. J. Cryst. Growth 24–25, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(74)90282-6 (1974).

Oxtoby, D. W. & Harrowell, P. R. The effect of density change on crystal growth rates from the melt. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 3834–3843. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.462864 (1992).

van de Waal, B. W. Can the lennard-jones solid be expected to be fcc?. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 3263–3266. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.3263 (1991).

Silvera, I. F. The solid molecular hydrogens in the condensed phase: Fundamentals and static properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 393–452. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.52.393 (1980).

Schuch, A. F., Mills, R. L. & Depatie, D. A. Crystal-structure changes in hydrogen and deuterium. Phys. Rev. 165, 1032–1040. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.165.1032 (1968).

Kühnel, M. et al. Time-resolved study of crystallization in deeply cooled liquid parahydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.245301 (2011).

Kozioziemski, B. J., Chernov, A. A., Mapoles, E. R. & Sater, J. D. Metastable polymorphs of hydrogen isotopes solidified near the triple point. Phys. Rev. Bhttps://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.82.012104 (2010).

Osychenko, O. N., Rota, R. & Boronat, J. Superfluidity of metastable glassy bulk \(<\) i \(>\) para \(<\) /i \(>\) -hydrogen at low temperature. Phys. Rev. Bhttps://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.85.224513 (2012).

Hu, J. & Boninsegni, M. Microscopic pair potentials and the physical properties of the condensed phases of parahydrogen. Appl. Sci.https://doi.org/10.3390/app1010000 (2020).

Schnepp, O. One-phonon excited states of solid h2 and d2 in the ordered phase. Phys. Rev. A 2, 2574–2574. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.2.2574 (1970).

Schumacher, M., Smend, F. & Borchert, I. Incoherent scattering of gamma rays by inner-shell electrons. J. Phys. B Atom. Mol. Phys. 8, 1428–1439. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3700/8/9/010 (1975).

Fletcher, L. B. et al. High resolution x-ray Thomson scattering measurements from cryogenic hydrogen jets using the linac coherent light source. Rev. Sci. Instum. 87, 11E524. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4959792 (2016).

Warren, B. E. Temperature diffuse scattering for cubic powder patterns. Acta Crystallogr. 6, 803–803. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x53002271 (1953).

Treacy, M. M. J., Newsam, J. M. & Deem, M. W. A general recursion method for calculating diffracted intensities from crystals containing planar faults. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 433, 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1991.0062 (1991).

Warren, B. X-ray Diffraction (Dover Publications, New York, 1990), dover edn.

Martin, S., Ullrich, C., Šimek, D., Martin, U. & Rafaja, D. Stacking fault model of \(\epsilon \)-martensite and its diffax implementation. J. App. Cryst. 44, 779–787. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889811019558 (2011).

Ahlers, G. Lattice heat capacity of solid hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 41, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1725656 (1964).

Gaines, J. R., Fedders, P. A., Collins, G. W., Sater, J. D. & Souers, P. C. Diffusion of atoms and molecules in the solid hydrogens. Phys. Rev. B 52, 7243–7251. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.52.7243 (1995).

O’Reilly, D. E. & Peterson, E. M. Self-diffusion of liquid hydrogen and deuterium. J. Chem. Phys. 66, 934–937. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.434001 (1977).

Kühnel, M. Time-resolved crystallization of deeply cooled liquid hydrogen isotopes. Ph.D. thesis, Institut für Kernphysik Frankfurt (2014).

Kim, J. B., Göde, S. & Glenzer, S. H. Development of a cryogenic hydrogen microjet for high-intensity, high-repetition rate experiments. Rev. Sci. Instum. 87, 11E328. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4961089 (2016).

Obst, L. et al. Efficient laser-driven proton acceleration from cylindrical and planar cryogenic hydrogen jets. Sci. Rep.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10589-3 (2017).

Liang, M. et al. The coherent x-ray imaging instrument at the linac coherent light source. J. Sync. Rad. 22, 514–519. https://doi.org/10.1107/s160057751500449x (2015).

White, D., Hu, J.-H. & Johnston, H. L. The heats of vaporization of para-hydrogen and ortho-deuterium from their boiling points to their critical temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. 63, 1181–1183. https://doi.org/10.1021/j150577a038 (1959).

Verkin, B. I. Handbook of Properties of Condensed Phases of Hydrogen and Oxygen (Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1991).

Roder, H. M. & Diller, D. E. Thermal conductivity of gaseous and liquid hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 52, 5928–5949. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1672877 (1970).

Souers, P. C. Hydrogen Properties for Fusion Energy (University of California Press, 1986).

Dean, J. & Lange, N. Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry. No. v. 15 in Lange’s handbook of chemistry (McGraw-Hill, 1999).

Ahlers, G. Lattice heat capacity of solid hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 41, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1725656 (1964).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the DOE Office of Science, Fusion Energy Science under FWP 100866, FWP 100182, and FWP 100237. The work here was carried out at the CXI end-station of the LCLS. Use of the LCLS, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F. wrote the manuscript, L.F., J.H., S.G., A.L. conceived of the experiment, L.F., A.L., E.M., J.K., M.F., M.J., B.O., C.S., P.S., J.H. conducted the experiment, E.A. supported analysis, A.A., T.L., M.L., S.B. supported setup and data collection, L.F., A.L., G.K., J.H. analyzed the results, S.H.G. funded and supervised experiment. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fletcher, L.B., Levitan, A.L., McBride, E.E. et al. X-ray diffraction of metastable structures from supercooled liquid hydrogen. Sci Rep 14, 17283 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67942-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67942-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Observation of a mixed close-packed structure in superionic water

Nature Communications (2025)