Abstract

This study aims to analyse the volumetric changes in brain MRI after cochlear implantation (CI), focusing on the speech perception in postlingually deaf adults. We conducted a prospective cohort study with 16 patients who had bilateral hearing loss and received unilateral CI. Based on the surgical side, patients were categorized into left and right CI groups. Volumetric T1-weighted brain MRI were obtained before and one year after the surgery. To overcome the artifact caused by the internal device in post-CI scan, image reconstruction method was newly devised and applied using the contralateral hemisphere of the pre-CI MRI data, to run FreeSurfer. We conducted within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis, based on the linear mixed effect models. When analyzing the contralateral cerebral hemisphere before and after CI, a substantial increase in superior frontal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus (STG) volumes was observed in the left CI group. A positive correlation was observed in the STG and post-CI word recognition score in both groups. As far as we know, this is the first study attempting longitudinal brain volumetry based on post-CI MRI scans. We demonstrate that better auditory performance after CI is associated with structural restoration in central auditory structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most recent Global Burden of Disease report (2019) estimated that 1.57 billion individuals, or one-fifth of the world population, are affected by hearing loss, with 62% over the age of 50 years1. The economic burden of hearing loss can be substantial, varying according to the severity and age of onset2. In addition to direct medical expenses, there are associated costs encompassing education, vocational factors, and decreased productivity3. Recent studies on age-related hearing loss have highlighted its association with enhanced risk of cognitive decline, depression, and social isolation4,5,6.

With the development of cochlear implant (CI) technology, many deaf patients who do not benefit from hearing aids can regain much of their hearing ability. However, there is a large variation in the level of hearing recovery. Many factors contribute to this variability, including the cause of deafness, age of deafness onset, duration of hearing deprivation, residual hearing, the integrity and shape of the cochlear nerve, duration of hearing aid use, whether the better or poorer hearing ear receives the implant, and the CI technology7,8,9,10,11. Another possible mechanism limiting post-CI speech performance after a period of auditory deprivation is cortical changes caused by hearing loss12,13. Limited hearing ability induces profound cortical changes in the brain; however, few studies have investigated these changes in post-lingually deaf adults. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are needed to track the dynamics of cortical changes that occur before and after implantation13.

Hearing loss has been also identified as the largest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia6. Thus, understanding the cortical changes involved would provide valuable insights into hearing loss-induced changes in the brain, and provide evidence for the mechanisms that underpin the association between hearing loss and dementia. Deafness and its rehabilitation through CI offer a unique model of cortical changes during hearing deprivation and recovery. MRI techniques now allow for the quantitative analysis of cortical changes as a function of the times of deafness. Recipients of CI can now undergo MRI up to 3T through the development of a new type of removable internal magnet with diametric polarization that rotates freely and aligns itself to the magnetic field.

The optimal method for evaluating changes in brain volume among patients with CI involves the longitudinal use of MRI, with a specific focus on quantifying the volume of distinct brain regions. However, acquiring accurate brain volume images post-CI is challenging due to distortions in T1-weighted images caused by paramagnetic artifacts. Nevertheless, previous studies have verified that these artifacts largely do not impact the cerebral cortex of the contralateral hemisphere, except for adjacent and posterior areas14.

We directly monitored changes in central auditory system, given the focus of our study was solely on assessing alterations in the opposite hemisphere. Various studies have reported the central auditory pathway to be dominant in the contralateral hemisphere during monoaural stimulation15,16,17. When auditory signals are restored through CI, significant structural changes are therefore expected to occur in the contralateral hemisphere. However, to reveal the volumetric changes in the brain cortices after CI necessitates overcoming several hurdles. For example, automatic parcellation software such as FreeSurfer, which delivers unbiased evaluations, segments brain areas during the initial reconstruction steps18. However, performing automatic parcellation (MRI volumetry) with FreeSurfer without intervention was challenging due to post-CI artifacts.

In this study, we introduce a novel pipeline specifically designed for the unbiased evaluation of cortical volume in the contralateral hemisphere following CI. We aimed to maximize the utility of FreeSurfer's recon-all step with minimal intervention. Moreover, our objective was to impartially determine the brain regions that correlate with the volume of the contralateral cortical area obtained through this process and its association with hearing.

Results

Among the 16 included patients, 11 were male (68.8%) and 5 were female (31.2%), with a mean age of 59.2 ± 16.9 (27–78) years. They were categorized into two groups based on the side in which CI was performed: the left CI group (n = 9) and the right CI group (n = 7). The specific details of the duration of deafness, CI usage period, and word recognition score (WRS) before and after surgery for each patient are described in Table 1. All patients used hearing aids prior to CI and had worn them for an average of 9.4 years. Before surgery, the unaided WRS for the non-CI ear averaged about 7.8% increasing to 20.5% in the aided state. For the CI ear, the unaided WRS was about 6.3%, showing a limited increase to 13.8% in the aided state (supplementary Table S1). There were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the groups. Pure tone audiometric thresholds were measured at frequencies of 500, 1K, 2K, and 4K Hz for both ears pre- and post-CI in each group (supplementary Fig. S1). In both groups, statistically significant improvements were observed across all four frequencies after CI (p < 0.001).

Volume alterations from pre-to-post CI

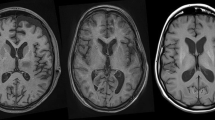

We performed validation within the two groups to analyze the change in voxel-based morphometry (VBM) by the CIs. We compared pre- and post-CI changes in cortical volume within the respective contralateral hemispheres to identify regions demonstrating statistically significant alterations (Fig. 1). During analysis of cortical volume changes across both groups, increases were noted in the superior frontal gyrus (SFG) and superior temporal gyrus (STG) in left CI group (Fig. 1 and supplementary Table S2). Only the region validated through vertex-wise clustering is marked with a red dashed line circle, and it was in the STG of right hemisphere. Lateral occipital regions were excluded from analysis due to potential artifact interference.

Statistical significance maps of pre- and post-CI cerebral cortex volumes in the contralateral hemisphere among the two groups. Statistical significance is represented through a color map: p < 0.05 = red and p < 0.01 = yellow. Vertex-wise clustering of volume alterations in the cerebral cortex of the contralateral hemisphere from pre- to post-CI in each group. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In the left CI group, a significant increase in volume was observed in the superior temporal gyrus of the right hemisphere. This change passed the vertex-wise cluster analysis (indicated by red dashed lines).

Correlation between volumetric alterations and post-CI WRS

We explored variations in post-CI WRS and identified correlations with rates of cortical change from pre-to-post-CI. We plotted significance maps for post-CI WRS against contralateral hemisphere cortical volume change for each group (Fig. 2 and supplementary Fig. S2). Correlation significance maps for volume change versus post-CI WRS near the STG revealed commonality across both hemispheres. These changes in the STG were confirmed through vertex-wise clustering validation.

Correlation between brain region volumetric alterations and post-cochlear implantation word recognition score (post-CI WRS). (a) Statistical maps illustrating regions of significant correlation between post-CI WRS and volumetric changes in the cerebral cortex of the contralateral hemisphere from pre- to post-CI. (b) Vertex-wise clustering analysis validates the association between the superior temporal gyrus (indicated by red dashed lines) with post-CI WRS in both the left and right hemispheres. Statistical significance is visually represented through a color map. p < 0.05 = red and p < 0.01 = yellow. The statistical significance of clustering was set at p < 0.05.

Correlation between volumetric alterations and post-CI WRS: simulated hemisphere model

While further participant recruitment is necessary to validate this correlation analysis definitively, we constructed a simulated hemisphere model by mirroring right-hemisphere data under the assumption of bilateral symmetry (Fig. 3). Regions demonstrating positive correlations included precentral gyri, postcentral gyri, STG, SFG, and paracentral lobules (supplementary Fig. S3); notably significant differences were observed specifically at the level of STG (Fig. 3 and supplementary Table S3; r = 0.51; P < 0.05). These findings suggest a meaningful association between post-CI WRS performance and volumetric changes induced by CI specifically at the level of STG.

Brain regions associated with volumetric alterations and post-cochlear implantation word recognition scores (post-CI WRS) in the simulated hemisphere. (a) The simulated hemisphere is constructed by reflecting the data from the right hemisphere, premised on the assumption of bilateral symmetry. (b and c) The high level of correlation significance noted in the superior temporal gyrus (STG, c) was similarly observed in the vertex-wise cluster analysis (p < 0.05). (d) A statistically significant correlation (r = 0.51, p < 0.05) was observed between the volumetric changes from pre- to post-operative stages and the post-CI WRS across the entire STG region.

Discussion

In an aging society with a high prevalence of age-related hearing loss that often develops during adulthood, postlingual deafness is now the major indication for CI. Unfortunately, studies regarding cortical volumetric changes by hearing loss in postlingually deaf CI adults are lacking compared with prelingually deaf patients. In this study, we found that the volume of contralateral STG increased significantly after CI, showing a positive correlation with post-CI speech perception ability.

Many studies have reported that the volume of STG, including the primary auditory cortex, decreases in patients with hearing loss. Peelle et al. conducted a VBM study that demonstrated a significant linear relationship between hearing ability and gray matter volume in the primary auditory cortex19. A recent study using VBM conducted in a cohort of 94 postlingually deaf adults showed significant GM decreases in the superior, middle, and inferior temporal cortices in postlingually deaf adults compared with the control group12. Glucose metabolism in deaf patients has also been reported to be significantly lower than that of control patients in the superior temporal cortices (BA41, BA42), indicating neuroplasticity in the adult auditory cortex in postlingual deafness20. This study did not compare the cortical volumes of the patients to those of the control group. However, the increase in the cortical volumes in the STG after CI suggests that hearing rehabilitation is associated with the reactivation of the hearing pathways, leading to the reversal of the volumetric decrease of the STG, including the primary auditory cortex.

In recent studies targeting hearing-impaired adults, a longitudinal study revealed accelerated volume reduction in the STG of the right hemisphere, while another study, utilizing vertex-wise partial correlation analyses, reported similar findings21,22. During the comparison of pre- and post-CI MRI, we observed significant changes only in the left CI group in the STG of the contralateral hemisphere. This suggests that this region undergoes the most sensitive changes in peripheral auditory conditions, in the context of adult hearing loss and recovered auditory stimulation after CI. In the left CI group, an increase in SFG, an area connected to Broca's area via corticocortical network fibers, was also observed23. Additionally, the decline in speech-in-noise reception ability in the elderly has been associated with the decrease in SFG22,24. Despite limited interpretation of the results owing to the small sample size, the potential for recovery of language function, including volume restoration in this area, through CI is notable.

A prior study demonstrated that the improvement in speech perception was accompanied by an increase in neural responses in the auditory cortex, which significantly enhanced amplitude and decreased latency of N1 auditory event-related potentials25. Additionally, auditory cortex activation increased and became focused in the primary auditory cortex with CI use for speech in a PET study26. These findings of recovered auditory electrophysiological evidence and glucose metabolism after CI indicate that the STG, including the primary auditory cortex, remains capable of processing acoustic input from the CI and leads to volumetric recovery after CI. This relatively quick recovery (within 1 year) observed in our patients occurs even in individuals with a long period of hearing deprivation. Several studies have reported a positive association between an increase in activation in the primary auditory cortex and the behavioral measures of speech perception using functional near-infrared spectroscopy and PET, resulting in a pattern similar to normal cortical activation in better-performing CI users27,28,29. Our study demonstrates the recovery of the auditory cortex concerning the processing of auditory stimuli correlates with the GM increase in the STG, including the primary auditory cortex, after CI with better speech perception ability. Improvement in speech perception ability therefore is associated with the recovery of responsiveness to auditory stimuli in the primary auditory cortex and volume after the period of hearing loss.

It has been demonstrated previously that declines in domain-specific cognition, including memory, verbal fluency, visuospatial ability, attentional test, and executive function test, were indicated to be associated with greater GM volume loss in the temporal regions30. The reduced hearing input from the ear leads to reduced neural activation, cortical re-organization, and atrophy across the brain areas involved in speech perception, suggesting that temporal atrophy may be an underlying mechanism in the association between hearing loss and cognitive declines31. We found the potential for the restoration of structural cortical change, particularly in the superior temporal region, through CI. Considering the speculated correlation of temporal area with cognitive functions, further investigation is required to determine whether inducing volume increases in this region is significantly related to cognitive functions. This exploration not only aims to elucidate the mechanisms behind hearing loss and cognitive function impairment but also seeks to ascertain whether auditory rehabilitation via CI has an impact on cognitive function recovery.

This study has several limitations. First, factors such as the duration of deafness, severity of hearing loss, and use of hearing aids before surgery, including specific details such as the direction and duration of use, as well as daily usage time, which might have influenced cortical changes, could not be controlled in the study group. Second, we did not include a control group to evaluate the cortical changes caused by hearing loss; however, this will be studied in the future. A third limitation relates to the absence of well-established anatomical limits of functional regions, which can differ from one brain atlas to another. Interindividual variability in brain anatomy can also complicate the comparisons. Lastly, heterogeneity in participant age, duration of hearing loss, and small sample sizes can lead to ambiguity in the interpretation of the results.

Additionally, limitations in image processing techniques also exist. Using SynthSR, we improved MRI data resolution for FreeSurfer compatibility, allowing robust brain region segmentation. However, resolution enhancement can introduce errors in volume estimation. Future research should consider higher-resolution MRI scans (1 mm slice thickness), enhancing FreeSurfer precision and improving post-CI brain volume change assessment.

In this study, we utilized a novel script that integrates artifact-free pre-CI MRI with post-CI MRI reconstructed manuals. This script facilitated longitudinal brain volume analysis using FreeSurfer, enabling the tracking of brain volume changes before and after surgery; however, it could not measure alterations in areas adjacent to the site of surgical intervention. Further refinements in methodology may be necessary to investigate brain changes in this area.

Conclusion

This is the first longitudinal study to track the cortical changes that occur after CI and their correlation with CI performance. Our study shows that the volume of contralateral STG increased significantly after CI, with a positive correlation with post-CI speech perception ability. These findings suggest that hearing rehabilitation could improve the structural recovery of the STG, which showed a positive relationship with speech perception ability, suggesting that CI can reverse structural and functional changes.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study that included adult patients aged 18 years of age and over with acquired bilateral severe-to-profound hearing loss who underwent unilateral CI at Asan Medical Center from May 2020 to May 2022. All included patients had bilateral hearing loss after language acquisition and were right-handed. Patients who were unable to undergo MRI or had other neurological conditions were excluded. In total, 16 patients were included in the analysis, all of whom underwent T1 MRI scans before and 1 year after CI. All patients underwent CI with full electrode insertion in one ear, with internal devices that were compatible with 3.0T MRI, so no preparatory steps were required for MRI scanning. Pre- and post-operative hearing evaluations, including speech audiometry, were conducted. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2020-0296). The entirety of the research was conducted under the supervision of the IRB in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Word recognition test as an outcome of CI

The outcome was assessed by open-set monosyllabic word recognition tests conducted in a quiet setting, as in conventional speech audiometry. We used 50 monosyllabic words spoken by a tester in an audio-only condition, with approximately 70 dB sound pressure level. The distance between the tester and the patient was 1 m. Patients were instructed to verbally reproduce the auditory stimuli, with the resulting scores for accurately identified keywords expressed as a percentage (%). The test was performed only with the CI, without the contralateral hearing aid. The results of the WRS conducted at the 1-year postoperative follow-up were used for analysis.

MRI acquisition

Presurgical MR images were obtained using a 3T MRI scanner (Ingenia, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) with an eight-channel coil. T1-weighted imaging was performed with the following parameters: TR/TE = 6.5–6.8/2.9–3.2 ms; FA = 9.0; FOV = 270; matrix = 512 × 512; thickness = 1–3 mm.

Post-CI MR was conducted 1-year after surgery, without removing the magnet of the internal device using a 3T MRI scanner (Skyra, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). T1-weighted 3D gradient echo images were acquired, in the axial, sagittal, and coronal plane: TR/TE = 1810/3 ms; FA = 9.0; FOV = 256 × 256; matrix = 512 × 512; thickness = 1–3 mm.

Image pre-processing (Fig. 4)

Procedure for MRI data pre-processing. (a) Postoperative axial image of three-dimensional T1-weighted imaging (3D-T1) data with signal loss attributable to the internal device of CI observed in the ipsilateral side (left hemisphere). (b) If the voxel size is greater than 1.5 mm, data reconstructed using synthetic super-resolution (SynthSR). (c) The surgical hemisphere with artifact is selectively excised and substituted by obtaining the corresponding hemisphere image from the preoperative T1 data of the same patient. The area delineated by red dashed lines indicates the incorporated ipsilateral hemisphere of the brain. (d) Final data include combined reconstructed data from the preoperative ipsilateral brain hemisphere.

Our preliminary step in image processing involved the application of synthetic super-resolution (SynthSR) to patient data following CI32,33. This procedure aimed to correct signal dropout in the cortical area and data surpassing a 1.5 mm iso-voxel due to artifacts. We employed the FreeSurfer image analysis suite, version 7.4.1 to perform the procedure (Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts; http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/).

Next, we implemented an unbiased script to replace the ipsilateral region from artifact-free MRI data acquired pre-CI with SynthSR reconstructed data gathered post-CI. Execution of the script proceeded in the following order:

-

1.

N4 bias field correction: performed on pre-and post-CI MRI data to correct MRI intensity inhomogeneity34.

-

2.

Brain Extraction (BET): conducted on pre- and post-CI MRI data35.

-

3.

Co-Registration (FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool, FLIRT): performed on pre- and post-CI MRI data using a six-degree rigid-body transformation35,36.

-

4.

Non-linear Registration (3dQwarp): executed to align pre-CI MRI data with the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard brain template (MNI152NLin2009cAsym)37.

-

5.

Transformation (3dNwarpApply and FLIRT): involved in preparing a modified ipsilateral part of the MNI standard brain mask into post-CI MRI space using inverse transform matrices35,36,37.

-

6.

Brain Replacement and Signal Intensity Optimization (FLIRT and 3dcalc): Carried out on the ipsilateral brain utilizing a binary brain mask35,36,38,39.

We used the MNI152nlin2009cAsym template, with voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3. The volume dimensions are 197 (x) × 233 (y) × 189 (z) voxels, with orientation in the left-posterior-inferior coordinate system. The coordinate origin is located near the anterior commissure.

All these processes were performed using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs; step 1. N4 bias field correction), FMRIB’s Software Library software (FSL; step2. BET, and steps 3, 5, and 6. FLIRT) and Analysis of Functional NeuroImages software package (AFNI; step 4. 3dQwarp, step 5. 3dNwarpApply, and step 6. 3dcalc). The permuted dataset obtained through this procedure was subsequently utilized in FreeSurfer's recon-all process.

Validation of the image pre-processing

To create artifact-free images suitable for brain volumetry analysis, we proposed a method of swapping the surgical hemisphere with the preoperative MRI of the same patient. To evaluate the reliability of this method, we conducted a rigorous validation experiment using pre-scan datasets. Specifically, we utilized artifact-free pre-scan data comprising 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 isovoxel 3D-T1 images. This process included the following steps:

-

1.

We selected pre-scan data from 13 subjects, ensuring the use of high-resolution 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 isovoxel 3D-T1 images.

-

2.

The entire process was automated using the pipeline described in our manuscript, without any manual intervention.

-

3.

For validation, we employed FreeSurfer’s SynthSeg to compare volumetric changes between the swapped/mirrored hemispheres and the native hemispheres.

-

4.

Instead of using the volume and thickness information of the swapped hemispheres directly from the FreeSurfer pipeline, we assessed the volumetric changes of the contralateral hemispheres for comparison.

-

5.

Our findings demonstrated that the volumetric changes across various regions were less than 1%, supporting the robustness and reliability of our methodology.

This thorough validation process confirms that our approach for handling hemisphere maintains data integrity and reliability.

Longitudinal analysis of the cortical surface

Initially, we visually inspected the pre-processed T1-weighted images to identify registration failures or additional artifacts. We then created cortical surface models for each participant using their post-CI T1 scans with the FreeSurfer. The models were generated at the boundaries formed by segmenting the gray and white matter of each anatomical volume through FreeSurfer's automated segmentation function40,41.

We then checked each model for segmentation inaccuracies and calculated sulcus labeling and anatomical landmark extraction from the cortical surface models of each participant. We applied FreeSurfer’s longitudinal processing function (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/LongitudinalProcessing) to create precise and unbiased cortical models from two independent scans for each participant42.

The steps involved in this longitudinal processing pipeline are as follows:

-

1.

Processing both T1-weighted images independently for each participant using the standard FreeSurfer procedure.

-

2.

Creating an intra-subject template space and image from these two independent images using robust, inverse consistent registration.

-

3.

After creating this base template, reprocessing of these independent cross-sectional images is performed.

-

4.

During reprocessing, several steps such as skull removal, Talairach transformation, atlas registration, spherical surface mapping, and segmentation are initialized with common information extracted from within-subject templates.

These steps significantly enhance reliability and statistical power while improving the robustness and sensitivity of the overall longitudinal analysis42. Following these reconstruction processes, we only used information related to the contralateral hemisphere relative to the CI surgical site43,44.

Vertex-wise clustering

Neuroimaging data typically involves analysing a large number of vertices simultaneously causing multiple comparison problem which can lead to a high rate of false positives. Vertex-wise clustering was conducted to address this problem and identify significant clusters in surface-based brain imaging data. Adjacent significant vertices are grouped into clusters. Cluster-based thresholding helps control the family-wise error rate or false discovery rate by focusing on clusters of significant vertices rather than individual vertices. Compute cluster statistics, such as the size of the cluster or the sum of statistical values within the cluster. Randomly reassign labels in the original data and perform multiple permutations. Repeat the clustering process for each permutation. Use the distribution of cluster statistics from the permutations to assess the significance of the clusters observed in the original data. Based on the results of VBM longitudinal analysis and vertex-wise clustering, we considered only the overlapping regions showing significant changes.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Haile, L. M. et al. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 397, 996–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00516-x (2021).

Mohr, P. E. et al. The societal costs of severe to profound hearing loss in the United States. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 16, 1120–1135. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462300103162 (2000).

Keren, R., Helfand, M., Homer, C., McPhillips, H. & Lieu, T. A. Projected cost-effectiveness of statewide universal newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics 110, 855–864. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.110.5.855 (2002).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868 (2013).

Manrique-Huarte, R., Calavia, D., Huarte Irujo, A., Giron, L. & Manrique-Rodriguez, M. Treatment for hearing loss among the elderly: Auditory outcomes and impact on quality of life. Audiol. Neurootol. 21(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000448352 (2016).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390, 2673–2734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6 (2017).

Friedland, D. R., Venick, H. S. & Niparko, J. K. Choice of ear for cochlear implantation: the effect of history and residual hearing on predicted postoperative performance. Otol. Neurotol. 24, 582–589 (2003).

Lazard, D. S. et al. Pre-, per- and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: A new conceptual model over time. PLoS One 7, e48739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048739 (2012).

Leung, J. et al. Predictive models for cochlear implantation in elderly candidates. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 131, 1049–1054. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.131.12.1049 (2005).

Kim, Y. et al. High-frequency cochlear nerve deficit region: relationship with deaf duration and cochlear implantation performance in postlingual deaf adults. Otol. Neurotol. 42, 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003092 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. Cochlear implantation in postlingually deaf adults is time-sensitive towards positive outcome: Prediction using advanced machine learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 8, 18004. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36404-1 (2018).

Sun, Z. et al. Cortical reorganization following auditory deprivation predicts cochlear implant performance in postlingually deaf adults. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25219 (2021).

Stropahl, M., Chen, L. C. & Debener, S. Cortical reorganization in postlingually deaf cochlear implant users: Intra-modal and cross-modal considerations. Hear Res. 343, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.07.005 (2017).

Sharon, J. D., Northcutt, B. G., Aygun, N. & Francis, H. W. Magnetic resonance imaging at 15 tesla with a cochlear implant magnet in place: Image quality and usability. Otol. Neurotol. 37, 1284–1290. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001176 (2016).

Langers, D. R., van Dijk, P. & Backes, W. H. Lateralization, connectivity and plasticity in the human central auditory system. Neuroimage 28, 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.024 (2005).

Schönwiesner, M., Krumbholz, K., Rübsamen, R., Fink, G. R. & von Cramon, D. Y. Hemispheric asymmetry for auditory processing in the human auditory brain stem, thalamus, and cortex. Cereb. Cortex 17, 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhj165 (2007).

Woldorff, M. G. et al. Lateralized auditory spatial perception and the contralaterality of cortical processing as studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging and magnetoencephalography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 7, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:1%3c49::AID-HBM5%3e3.0.CO;2-J (1999).

Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021 (2012).

Peelle, J. E., Troiani, V., Grossman, M. & Wingfield, A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. J. Neurosci. 31, 12638–12643. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2559-11.2011 (2011).

Lee, J. S. et al. PET evidence of neuroplasticity in adult auditory cortex of postlingual deafness. J. Nucl. Med. 44, 1435–1439 (2003).

Lin, F. R. et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage 90, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.059 (2014).

Neuschwander, P. et al. Different neuroanatomical correlates for temporal and spectral supra-threshold auditory tasks and speech in noise recognition in older adults with hearing impairment. Eur. J. Neurosci. 57, 981–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15922 (2023).

Ookawa, S. et al. Frontal fibers connecting the superior frontal gyrus to Broca area: A corticocortical evoked potential study. World Neurosurg. 107, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.166 (2017).

Giroud, N., Keller, M. & Meyer, M. Interacting effects of frontal lobe neuroanatomy and working memory capacity to older listeners’ speech recognition in noise. Neuropsychologia 158, 107892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107892 (2021).

Sandmann, P. et al. Rapid bilateral improvement in auditory cortex activity in postlingually deafened adults following cochlear implantation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126, 594–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.06.029 (2015).

Giraud, A. L., Truy, E. & Frackowiak, R. Imaging plasticity in cochlear implant patients. Audiol. Neurootol. 6, 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1159/000046847 (2001).

Olds, C. et al. Cortical activation patterns correlate with speech understanding after cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 37, e160-172. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000258 (2016).

Green, K. M., Julyan, P. J., Hastings, D. L. & Ramsden, R. T. Auditory cortical activation and speech perception in cochlear implant users: Effects of implant experience and duration of deafness. Hear Res. 205, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.016 (2005).

Naito, Y. et al. Increased cortical activation during hearing of speech in cochlear implant users. Hear Res. 143, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00035-6 (2000).

Armstrong, N. M. et al. Associations between cognitive and brain volume changes in cognitively normal older adults. Neuroimage 223, 117289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117289 (2020).

Slade, K. et al. The impact of age-related hearing loss on structural neuroanatomy: A meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 13, 950997. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.950997 (2022).

Iglesias, J. E. et al. Joint super-resolution and synthesis of 1 mm isotropic MP-RAGE volumes from clinical MRI exams with scans of different orientation, resolution and contrast. Neuroimage 237, 118206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118206 (2021).

Iglesias, J. E. et al. SynthSR: A public AI tool to turn heterogeneous clinical brain scans into high-resolution T1-weighted images for 3D morphometry. Sci. Adv. 9, 3607. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.add3607 (2023).

Avants, B. B. et al. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage 54, 2033–2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025 (2011).

Smith, S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.10062 (2002).

Greve, D. N. & Fischl, B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage 48, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.060 (2009).

Saad, Z. S. et al. A new method for improving functional-to-structural MRI alignment using local Pearson correlation. Neuroimage 44, 839–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.037 (2009).

Cox, R. W. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput. Biomed. Res. 29, 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014 (1996).

Cox, R. W. & Hyde, J. S. Software tools for analysis and visualization of fMRI data. NMR Biomed. 10, 171–178 (1997).

Dale, A. M., Fischl, B. & Sereno, M. I. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 9, 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 (1999).

Fischl, B. & Dale, A. M. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 97, 11050–11055. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.200033797 (2000).

Reuter, M., Schmansky, N. J., Rosas, H. D. & Fischl, B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage 61, 1402–1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084 (2012).

Woo, C.-W., Krishnan, A. & Wager, T. D. Cluster-extent based thresholding in fMRI analyses: pitfalls and recommendations. Neuroimage 91, 412–419 (2014).

Greve, D. N. & Fischl, B. False positive rates in surface-based anatomical analysis. Neuroimage 171, 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.072 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design were contributed by H.H., W.H.S., and H.J.P. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data was performed by Y.J.L., H.A.J., and Y.C. Drafting of the manuscript was primarily conducted by Y.J.L., H.H., and H.J.P. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content was carried out by H.H., W.H.S., and H.J.P. Statistical analysis was conducted by Y.J.L. and H.H. Administrative, technical, or material support was provided by H.H. and W.H.S. Supervision was overseen by W.H.S. and H.J.P. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y.J., Heo, H., Joo, H.A. et al. Cortical volumetric changes after cochlear implantation in postlingually deaf adults: correlation with speech perception abilities. Sci Rep 14, 17524 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68002-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68002-9