Abstract

The three-dimensional heads-up display system (3D HUDS) is increasingly utilized by ophthalmologists and suggested to offer ergonomic benefits compared to conventional operating microscopes. We aimed to quantitatively assess the surgeon’s neck angle and musculoskeletal discomfort during cataract surgery using commercially available 3D HUDS and conventional microscope. In this single-center comparative observational study, the surgeon conducted routine phacoemulsification surgeries using Artevo® 800 and Opmi Lumera® 700 (both from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany). The surgeon’s intraoperative neck angle was measured using the Cervical Range of Motion device. Postoperative musculoskeletal discomfort was assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score after each surgery. A total of 80 cataract surgeries were analyzed, with 40 using Artevo® 800 and 40 using Opmi Lumera® 700. The neck angle was extended when using Artevo® 800 and flexed when using Opmi Lumera® 700 during continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC), phacoemulsification, and intraocular lens (IOL) placement (− 8.18 ± 2.85° vs. 8.27 ± 2.93° in CCC, − 7.83 ± 3.30° vs. 8.87 ± 2.83° in phacoemulsification, − 7.43 ± 3.80° vs. 7.67 ± 3.73° in IOL placement, respectively; all p < 0.001). The VAS score was significantly lower in surgeries performed with Artevo® 800 (1.27 ± 0.55 vs. 1.73 ± 0.64, p < 0.001). The findings suggest that 3D HUDS help reduce neck flexion and lower work-related musculoskeletal discomfort through ergonomic improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the introduction of modern surgical microscopes in the 1940s, these devices have been central to practices in cataract surgery1,2. Recent years have seen significant advancements in the field, including surgical techniques, phacoemulsification machine designs, and intraocular lens technologies3. First introduced in 19994, the three-dimensional heads-up display system (3D HUDS) is one of the burgeoning innovations. It is increasingly used by ophthalmologists in the last two decades and enhances visualization of surgical fields by projecting the view to a 3D monitor5,6.

3D HUDS-based ophthalmic surgery is reported to offer several advantages: better ergonomics for surgeons, enhanced depth perception and visualization of peripheral surgical field, reduced phototoxicity, and improved teaching opportunities7,8,9,10,11,12,13. 3D HUDS offer similar safety and efficiency as the traditional binocular microscope8,14,15. However, reported potential limitations include possible time lags, financial costs, the need for additional operating room space, a slow learning curve, and longer surgical times during early uses6,7,16. Nonetheless, experienced cataract surgeons typically adapt to this tool after 25–50 cases, after which there are no differences in the surgical times or complication rates17.

Whereas the conventional ophthalmic surgical microscopes with its binocular viewing systems require surgeons to adapt their posture to get to the eyepieces, 3D HUDS allow surgeons more unrestricted and natural postures18 (Fig. 1). Therefore, the system enables the surgeon to operate in “heads-up” position; a more neutral body position and move freely without compromising image quality. 3D HUDS users reported improved musculoskeletal symptoms10,13, suggesting adopting this new technology provides opportunities for better ergonomics for ophthalmologists.

Optimizing ergonomics in surgery is crucially important, impacting both the productivity and career longevity of surgeons, which must not be overlooked19. Unfortunately, work-related musculoskeletal disorders are a prevalent issue among ophthalmologists worldwide, with an increased prevalence associated with more time spent in surgery20,21,22,23,24. Eye care providers report a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal pain compared to family medicine physicians due to repetitive tasks and awkward working positions, underlining the need for workplace modifications25. Neck, back, and shoulder pain are frequently reported10,26.

Artevo® 800 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany), a digitally integrated 3D microscope, has demonstrated its efficacy and safety through years of experiences15. It provides a real-time stereoscopic view of the surgical field on a wide-screen 4 K monitor, offering true colors, improved resolution, enhanced depth of focus, and excellent visualization15,17.

Previous studies on the ergonomic differences associated with the use of 3D heads-up display systems (3D HUDS) have primarily relied on survey data, resulting in inherently subjective outcomes9,10,13. To date, few studies have quantitatively assessed the intraoperative body positions of ophthalmologists. This study aimed to quantitatively evaluate the neck positions and musculoskeletal discomfort of surgeon during cataract surgery when using Artevo® 800, in comparison to a conventional binocular microscope.

Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the principles dictated in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB number: P01-202,405-01-027) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. All patient data were treated anonymously following privacy regulations. The requirement for written informed consent was waived because of the study design and utilization of unidentified data.

This is a single-center, comparative observational case-series study conducted at Fatima Eye Clinic, Changwon, Korea, an ophthalmology-dedicated clinic staffed by four full-time ophthalmologists. The study included consecutive patients older than 40 years with uncomplicated cataracts who were scheduled for routine phacoemulsification surgery between August 11, 2023 and November 7, 2023. Exclusion criteria were patients with a history of previous intraocular surgery, coexisting vision-threatening diseases such as wet age-related macular degeneration or corneal diseases that compromise transparency, cataracts with significant subluxation or phacodonesis. Data of patients who underwent cataract surgery on both eyes were analyzed separately.

Data collected from patients included age and sex, preoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and spherical equivalent (SE), postoperative BCVA at the 1-month visit, and the severity of cataracts according to Lens Opacities Classification System (LOCS III). BCVA measurements were taken using the Snellen chart and later converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution(logMAR) scale for analysis. Operation times were recorded, measuring from the start of corneal incision to the removal of the microscope from the surgical field.

Data collected from the surgeon included neck angles and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores. The Cervical Range of Motion (CROM) device (Performance Attainment Associates, Minnesota, USA) is designed to measure cervical range of motion in the three cardinal planes (Fig. 2). The CROM device was worn by the surgeon to measure neck position during active periods of surgical procedures. Neck angle was estimated by reading the scale, to the nearest 1°, on the temporally located inclinometer of the device to assess the degree of neck flexion or extension, during continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC), phacoemulsification, and intraocular lens (IOL) placement. Measurements were taken by a third observer in the operating room when the surgeon’s position was kept stable. Positive angles indicate flexion, while negative angles indicate extension. The device was calibrated at the start of each day. After each surgery, the surgeon immediately recorded VAS score to assess subjective postoperative musculoskeletal discomfort. On this scale, a score of 0 represents no discomfort at all and a score of 10 represents the worst possible discomfort.

Data collection was done by a single surgeon experienced in using both 3D HUDS and conventional binocular microscope. The clinic’s operating room was equipped with two microscopes during the study period: Artevo® 800 and Opmi Lumera® 700 microscope (both from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany). Artevo® 800 provides 3D HUDS, while Opmi Lumera® 700 is a conventional microscope with oculars for viewing. A 55-inch 3D monitor supported on a movable cart was used for display with Artevo® 800 (Fig. 3).

The surgeon was positioned at lateral side of the patient and made a clear corneal incision on the temporal side. Cataract operations were performed under topical anesthesia using the Centurion Vision System (Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas, USA) phacoemulsification machine for all patients. The surgeries were performed using the two types of microscopes in alternating sequence throughout the study period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were reported as frequency (percentage). Group differences were assessed using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test when the normality assumption was not met, or the chi-square test for categorical variables. All tests were two-tailed, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses and generation of graphs were performed using Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft, Los Angeles, California, USA), IBM SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Chicago, Illinois, USA), and GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

A total of 80 cataract surgeries (50 patients) were included in this study, with 40 surgeries performed using Artevo® 800 and another 40 using Opmi Lumera® 700. No intraoperative complications, such as nucleus drop, radial tear, or requirement of anterior vitrectomy, were observed in any of the 80 cases. Although Artevo® 800 is equipped with both 3D HUDS and conventional eyepieces, allowing for intraoperative conversion, no conversions to the binocular viewing system were necessary during the surgeries performed with Artevo® 800.

Baseline patient characteristics associated with each microscope are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in laterality, age, preoperative logMAR BCVA, preoperative SE, or the proportion of dense nuclear cataracts between two groups. A higher proportion of female patients was observed in Artevo® 800 group (65.0% vs. 37.5%, p = 0.014).

Intraoperative and postoperative patient outcomes are detailed in Table 2. Postoperative logMAR BCVA at 1 month was 0.033 ± 0.117 for 3D HUDS and 0.021 ± 0.048 for the conventional microscope, with no significant difference (p = 0.972). Surgical times were 597 ± 90 s for Artevo® 800 and 600 ± 150 s for Opmi Lumera® 700, also with no significant difference (p = 0.430). Postoperative SE was not included due to inconsistent target diopters.

Neck angles measured during surgeries with Artevo® 800 were predominantly negative, indicative of neck extension, whereas measurements taken Opmi Lumera® 700 were generally positive, indicating neck flexion. Significant differences in neck angles were observed during CCC, phacoemulsification, and IOL placement (− 8.18 ± 2.85° vs. 8.27 ± 2.93° in CCC, − 7.83 ± 3.30° vs. 8.87 ± 2.83° in phacoemulsification, − 7.43 ± 3.80° vs. 7.67 ± 3.73° in IOL placement, respectively, with all p < 0.001). The mean absolute neck angle was calculated as the absolute value of the average of these three measurements to represent the magnitude of neck deviation, regardless of direction (flexion or extension). The mean deviation from neutral neck position did not show a significant difference (7.80 ± 2.83 vs. 8.29 ± 2.88, p = 0.362).

Box plots representing neck angles are shown in Fig. 4. For Artevo® 800, the interquartile ranges (IQR) were − 10.00° to − 7.25° for CCC, − 10.00° to − 6.25° for phacoemulsification, and − 10.00° to − 3.25° for IOL placement. These did not overlap with the IQRs for Opmi Lumera® 700, which were 8.00–10.00° for CCC, 8.00–11.00° for phacoemulsification, and 7.00–10.00° for IOL placement.

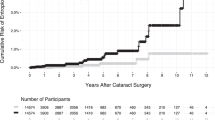

The postoperative VAS scores were significantly lower for surgeries conducted with Artevo® 800 (1.27 ± 0.55 vs. 1.73 ± 0.64, p < 0.001). No cases with VAS score equal to or greater than 4 were reported. The distribution of VAS scores is shown in Fig. 5.

Discussion

The use of slit lamps, indirect ophthalmoscopes, surgical loupes, surgical microscopes, and computers place stress on the shoulders, neck, and back of ophthalmologists. This stress results from poor posture and repetitive movements during ocular examinations and surgeries, which are considered modifiable risk factors27. Several reviews emphasize the necessity for ergonomic adjustments and provide guidelines for addressing these factors in operating rooms, including practical recommendations27,28,29 (Fig. 6).

This study used basic patient data, neck angles measured with the CROM device, and VAS scores to compare intraoperative and postoperative outcomes, surgeon’s postures and musculoskeletal discomfort in cataract operations performed with either 3D HUDS or a conventional microscope. It differs from previous reports in that it is one of the first to investigate the ergonomic differences of 3D HUDS using quantitative measurements taken during individual surgeries.

Surgical times, visual acuity outcomes, and intraoperative complications did not differ between the two groups, aligning with findings from previous studies14,17. According to the assumptions in the same study, the comparable surgical times in the two groups suggest that the surgeon had completed the learning curve for 3D HUDS17.

Neck angles were predominantly flexed, with a mean value of 7.80°, when using conventional microscopes with oculars, and extended, with a mean value of 8.29°, when using 3D HUDS. In both cases, deviation from neutral point was minor, mostly less than 10°. Neck flexion in conventional microscope is due to the design of the microscope, necessitating leaning forward to peer into the oculars. Conversely, 3D HUDS enable surgeons to maintain a more upright posture, as they focus on the 3D monitor positioned in front of them.

Experience with 3D HUDS in terms of image quality, neck strain, and eye strain can be influenced by factors such as viewing tilt angle, monitor distance and height, chair height, and laterality of the eye30. For endoscopic procedures in rhinology, it is recommended that monitors be placed directly in front of the surgeon, between 80 and 120 cm from the surgeon’s eyes, and at or below eye level31,32,33. Although these recommendations may not directly apply to ophthalmic surgeries using 3D HUDS, they highlight the importance of proper monitor placement.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no established consensus on the optimal positioning of the display in 3D HUDS. In one study on cataract surgery using 3D HUDS, the average eye-to-monitor distance was 170 cm, and a closer monitor (distance of 127–140 cm) caused less eye strain30. Optimal distance and height vary with different displays, and the perception of 3D dimensionality differs among observers, suggesting the need for individualized settings for optimal results34. In our study, we measured the eye-to-monitor distance to be between 140 and 150 cm. The floor-to-monitor height (measured from the floor to the central point of the display) was 135 cm. However, these measurement were not consistently taken and likely varied slightly, as the monitor often needed to be moved according to the laterality of the operating eye. Optimizing the eye-to-monitor distance and the monitor height according to the surgeon could help achieve a neutral neck position, potentially eliminating the minor degree of neck extension observed in this study.

The VAS is an appropriate and valid tool for clinical use, exhibiting good inter-test and test–retest reliability35,36. However, its efficacy has primarily been studied for evaluating patient pain, and multiple-question reporting systems have been reported to provide superior assessment37,38. The VAS is a self-reporting tool, and it is unfeasible to conceal the type of microscope used during operations from surgeons. Therefore, the VAS results were susceptible to bias.

The CROM device allows noninvasive measurement of neck angles and is a reliable clinical tool used in many studies to assess neck movements39,40. However, one limitation is that it can only measure at a single moment and cannot record changes over time. Additionally, this study did not include neck rotation or lateral bending into analysis. While the CROM device provides reliable measurements of forward head posture, it requires additional components and steps41, limiting its use during active surgical performance.

This study reported reduced postoperative discomfort with the use of 3D HUDS, compared to conventional microscopes. The load on the cervical spine increases progressively with the degree of flexion; tilting the neck forward by 15 degrees increases the load by 2.5 times relative to a neutral position42. For ophthalmologists who suffer from leaning forward and forward head posture when using conventional microscopes, 3D HUDS is expected to provide a greater benefit. We hypothesized that 3D HUDS promote a neutral body and neck position, potentially decreasing musculoskeletal discomfort for surgeons. However, although neck flexion was eliminated with the use of 3D HUDS, neck extension with a similar absolute degree of deviation from the neutral point was still observed. From these findings, the improvement in postoperative discomfort cannot be fully explained by changes in neck angle alone. It could be attributed to other ergonomic benefits, such as the resolution of hunched back, correction of forward head posture, and enabling free movement without the need to remain fixed to the microscope oculars. Additionally, one study recently demonstrated that conventional microscopes cause more fatigue in the sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius muscles compared to 3D HUDS in vitreoretinal and phacoemulsification surgeries43. A survey of Japanese ophthalmologists showed 72% had a neutral neck posture and 61% had a neutral back position with 3D HUDS, compared to 34% and 33% with conventional microscopes, respectively44.

This study, along with recent studies on ergonomic benefits of 3D HUDS10,43,44, reinforces that 3D HUDS is effective for improving surgeon ergonomics and reducing musculoskeletal discomfort. However, there are a few points to consider before strongly advocating for the use of 3D HUDS for ergonomic purposes. Ergonomic positions could also be achieved, at least partially, by other methods such as use of ocular extenders, moving the oculars 20–25° toward the surgeon, or timely re-adjusting the patient’s head position27,28. Additionally, 3D HUDS faces its own ergonomic challenges, such as extra neck tilting due to the viewing system being positioned above the patient’s head, which impedes an exact straight-line position relative to the surgeon, and awkward head rotation for the assistant positioned perpendicularly to the operating surgeon45,46.

There are several limitations to acknowledge in this study. First, there was no standardized setting for the operating rooms, which may have influenced the surgeon’s positions during surgery with 3D HUDS, such as monitor height or distance. Additionally, the assessment of the surgeon’s position and musculoskeletal discomfort relied on relatively simple methods. Other methods used in ergonomic studies to measure muscular burden or assess movements, if extended to fields other than ophthalmology, include myotonometer, electromyography, inertial measurement unit sensors, and Rapid Entire Body Assessment43,47,48,49,50. Other tools, such as the NASA Task Load Index and the Borg scale, are also reported for assessing the perceived exertion of surgeons30,48. Lastly, the study included only a single surgeon, and positioning with conventional microscopes and 3D HUDS can vary individually44.

In conclusion, we quantitatively measured neck angles and assessed postoperative musculoskeletal discomfort in cataract surgery to compare 3D HUDS and conventional microscopes. Our results suggest that adopting 3D HUDS can resolve neck flexion during surgery and alleviate ophthalmologists’ postoperative musculoskeletal discomfort. Further studies investigating intraoperative ergonomic positions and measuring surgeon fatigue, involving multiple ophthalmologists, are warranted.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Ma, L. & Fei, B. Comprehensive review of surgical microscopes: Technology development and medical applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 26, 010901–010901 (2021).

Uluç, K., Kujoth, G. C. & Başkaya, M. K. Operating microscopes: Past, present, and future. Neurosurg. Focus 27, E4 (2009).

Sachdev, M. Cataract surgery: The journey thus far. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 65, 1273–1274 (2017).

Miyake, K. et al. Application of a newly developed, highly sensitive camera and a 3-dimensional high-definition television system in experimental ophthalmic surgeries. Arch. Ophthalmol. 117, 1623–1629 (1999).

Moura-Coelho, N., Henriques, J., Nascimento, J. & Dutra-Medeiros, M. Three-dimensional display systems in ophthalmic surgery–A review. Eur. Ophthalm. Rev. 117, 1623 (2019).

Muecke, T. P. & Casson, R. J. Three-dimensional heads-up display in cataract surgery: A review. Asia-Pacific J. Ophthalmol. 11, 549–553 (2022).

Razavi, P., Cakir, B., Baldwin, G., D’Amico, D. J. & Miller, J. B. Heads-up three-dimensional viewing systems in vitreoretinal surgery: An updated perspective. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 2539–2552 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Three-dimensional heads-up cataract surgery using femtosecond laser: Efficiency, efficacy, safety, and medical education—a randomized clinical trial. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 10, 4–4 (2021).

Bin Helayel, H., Al-Mazidi, S. & AlAkeely, A. Can the three-dimensional heads-up display improve ergonomics, surgical performance, and ophthalmology training compared to conventional microscopy. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 679–686 (2021).

Weinstock, R. J. et al. Comparative assessment of ergonomic experience with heads-up display and conventional surgical microscope in the operating room. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 347–356 (2021).

Rosenberg, E. D., Nuzbrokh, Y. & Sippel, K. C. Efficacy of 3D digital visualization in minimizing coaxial illumination and phototoxic potential in cataract surgery: Pilot study. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 47, 291–296 (2021).

Cheng, T. C. et al. Evaluation of three-dimensional heads up ophthalmic surgery demonstration from the perspective of surgeons and postgraduate trainees. J. Craniofac. Surg. 32, 2285–2291 (2021).

Tan, N. E., Wortz, B. T., Rosenberg, E. D., Radcliffe, N. M. & Gupta, P. K. Impact of heads-up display use on ophthalmologist productivity, wellness, and musculoskeletal symptoms: A survey study. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 34, 305–311 (2022).

Weinstock, R. J., Diakonis, V. F., Schwartz, A. J. & Weinstock, A. J. Heads-up cataract surgery: Complication rates, surgical duration, and comparison with traditional microscopes. J. Refract. Surg. 35, 318–322 (2019).

Del Turco, C. et al. Heads-up 3D eye surgery: Safety outcomes and technological review after 2 years of day-to-day use. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 1129–1135 (2022).

Kaur, M., Nair, S. & Titiyal, J. S. Commentary: Three-dimensional heads-up display system for cataract surgery. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69, 2309–2310 (2021).

Kelkar, J. A., Kelkar, A. S. & Bolisetty, M. Initial experience with three-dimensional heads-up display system for cataract surgery–A comparative study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69, 2304–2309 (2021).

Srinivasan, S., Tripathi, A. B., & Suryakumar, R. Evolution of operating microscopes and development of 3D visualization systems for intraocular surgery. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. (2022).

Schlussel, A. T. & Maykel, J. A. Ergonomics and musculoskeletal health of the surgeon. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 32, 424–434 (2019).

Hyer, J. N. et al. National survey of back & neck pain amongst consultant ophthalmologists in the United Kingdom. Int. Ophthalmol. 35, 769–775 (2015).

Diaconita, V., Uhlman, K., Mao, A. & Mather, R. Survey of occupational musculoskeletal pain and injury in Canadian ophthalmology. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 54, 314–322 (2019).

Venkatesh, R. & Kumar, S. Back pain in ophthalmology: National survey of Indian ophthalmologists. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 65, 678–682 (2017).

Schechet, S. A., DeVience, E., DeVience, S., Shukla, S. & Kaleem, M. Survey of musculoskeletal disorders among US ophthalmologists. Digit. J. Ophthalmol. DJO 26, 36 (2020).

Al-Marwani Al-Juhani, M., Khandekar, R., Al-Harby, M., Al-Hassan, A. & Edward, D. Neck and upper back pain among eye care professionals. Occup. Med. 65, 753–757 (2015).

Kitzmann, A. S. et al. A survey study of musculoskeletal disorders among eye care physicians compared with family medicine physicians. Ophthalmology 119, 213–220 (2012).

Dhimitri, K. C. et al. Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 139, 179–181 (2005).

Honavar, S. G. Head up, heels down, posture perfect: Ergonomics for an ophthalmologist. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 65(8), 647 (2017).

Betsch, D., Gjerde, H., Lewis, D., Tresidder, R. & Gupta, R. R. Ergonomics in the operating room: It doesn’t hurt to think about it, but it may hurt not to!. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 55, 17–21 (2020).

Alrashed, W. A. Ergonomics and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmic practice. Imam J. Appl. Sci. 1, 48–63 (2016).

Gupta, Y. & Tandon, R. Optimization of surgeon ergonomics with three-dimensional heads-up display for ophthalmic surgeries. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70, 847 (2022).

Ramakrishnan, V. R. & Montero, P. N. Ergonomic considerations in endoscopic sinus surgery: Lessons learned from laparoscopic surgeons. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 27, 245–250 (2013).

Ayad, T., Peloquin, L. & Prince, F. Ergonomics in endoscopic sinus surgery: Systematic review of the literature. J. Otolaryngol. 34, 333–340 (2005).

Kelts, G. I., McMains, K. C., Chen, P. G. & Weitzel, E. K. Monitor height ergonomics: A comparison of operating room video display terminals. Allergy Rhinol. 6, ar.2015 (2015).

Tsuboi, K., Shiraki, Y., Ishida, Y., Shibata, T. & Kamei, M. Optimal display positions for heads-up surgery to minimize crosstalk. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 28–28 (2020).

Alghadir, A. H., Anwer, S., Iqbal, A. & Iqbal, Z. A. Test–retest reliability, validity, and minimum detectable change of visual analog, numerical rating, and verbal rating scales for measurement of osteoarthritic knee pain. J. Pain Res. 11, 851–856 (2018).

Karcioglu, O., Topacoglu, H., Dikme, O. & Dikme, O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use?. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 707–714 (2018).

Rahbek, O. et al. Inferior reliability of VAS scoring compared with International Society of the Knee reporting system for abstract assessment. Dan Med. J. 64, A5346 (2017).

Shukla, R. H., Nemade, S. V. & Shinde, K. J. Comparison of visual analogue scale (VAS) and the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) score in evaluation of post septoplasty patients. World J. otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 6, 53–58 (2020).

Wibault, J., Vaillant, J., Vuillerme, N., Dedering, Å. & Peolsson, A. Using the cervical range of motion (CROM) device to assess head repositioning accuracy in individuals with cervical radiculopathy in comparison to neck-healthy individuals. Manual Therapy 18, 403–409 (2013).

Correia, I. M. T. et al. Association between text neck and neck pain in adults. Spine 46, 571–578 (2021).

Garrett, T. R., Youdas, J. W. & Madson, T. J. Reliability of measuring forward head posture in a clinical setting. J. Orthopaed. Sports Phys. Therapy 17, 155–160 (1993).

Hansraj, K. K. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg. Technol. Int. 25, 277–279 (2014).

Park, S. J., Hwang, J.-M., Park, E. J. J., Shin, J. P. & Park, D. H. Comparison of surgeon muscular properties between standard operating microscope and digitally assisted vitreoretinal surgery systems. Retina 42, 1583–1591 (2022).

Kamei, M. et al. Ergonomic benefit using heads-up display compared to conventional surgical microscope in Japanese ophthalmologists. PLoS ONE 19, e0297461 (2024).

Kaur, M. & Titiyal, J. S. Three-dimensional heads up display in anterior segment surgeries-Expanding frontiers in the COVID-19 era. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 68, 2338–2340 (2020).

Rizzo, S. et al. 3D surgical viewing system in ophthalmology: Perceptions of the surgical team. Retina 38, 857–861 (2018).

Ramakrishnan, V. R. & Milam, B. M. Ergonomic analysis of the surgical position in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 7, 570–575 (2017).

Arrighi-Allisan, A. E. et al. Ergonomic analysis of otologic Surgery: Comparison of endoscope and microscope. Otol. Neurotol. 44, 542–548 (2023).

Joo, H. et al. Intraoperative neck angles in endoscopic and microscopic otologic surgeries. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 168(6), 1494–1501 (2023).

Hilt, L. et al. Bariatric Surgeon ergonomics: A comparison of laparoscopy and robotics. J. Surg. Res. 295, 864–873 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: 1711196706, RS-2023-00253749). The funding organizations had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation and data collection were performed by J.J; B.K. and Y.S. analyzed the data. S.S. prepared visualization of the figures; Y.S. wrote the main manuscript text, tables, and figures; J.J. and T.K. supervised the project and revised the manuscript; All authors discussed the results and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suh, Y., Shin, S., Kim, B.Y. et al. Comparison of neck angle and musculoskeletal discomfort of surgeon in cataract surgery between three-dimensional heads-up display system and conventional microscope. Sci Rep 14, 22681 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68630-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68630-1