Abstract

Visceral adiposity index (VAI) is a reliable indicator of visceral adiposity. However, no stu-dies have evaluated the association between VAI and DKD in US adults with diabetes. Theref-ore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between them and whether VAI is a good pr-edictor of DKD in US adults with diabetes. Our cross-sectional study included 2508 participan-ts with diabetes who were eligible for the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2007 to 2018. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to an-alyze the association between VAI level and DKD. Three models were used to control for pot-ential confounding factors, and subgroup analysis was performed for further verification. A tot-al of 2508 diabetic patients were enrolled, of whom 945 (37.68%) were diagnosed with DKD. Overall, the VAI was 3.36 ± 0.18 in the DKD group and 2.76 ± 0.11 in the control group. VAI was positively correlated with DKD (OR = 1.050, 95% CI 1.049, 1.050) after fully adjusting for co-nfounding factors. Compared with participants in the lowest tertile of VAI, participants in the highest tertile of VAI had a significantly increased risk of DKD by 35.9% (OR = 1.359, 95% CI 1.355, 1.362). Through subgroup analysis, we found that VAI was positively correlated with the occurrence of DKD in all age subgroups, male(OR = 1.043, 95% CI 1.010, 1.080), participants wit-hout cardiovascular disease(OR = 1.038, 95% CI 1.011, 1.069), hypertension (OR = 1.054, 95% CI 1.021, 1.090), unmarried participants (OR = 1.153, 95% CI 1.036, 1.294), PIR < 1.30(OR = 1.049, 95% CI 1.010, 1.094), PIR ≧ 3 (OR = 1.085, 95% CI 1.021, 1.160), BMI ≧ 30 kg/m2 (OR = 1.050, 95% CI 1.016, 1.091), former smokers (OR = 1.060, 95% CI 1.011, 1.117), never exercised (OR = 1.033, 95% CI 1.004, 1.067), non-Hispanic white population (OR = 1.055, 95% CI 1.010, 1.106) and non-Hipanic black population (OR = 1.129, 95% CI 1.033, 1.258). Our results suggest that elevated VAI levels are closely associated with the development of DKD in diabetic patients. VAI may be a simpl-e and cost-effective index to predict the occurrence of DKD. This needs to be verified in furt-her prospective investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes (DM) is one of the most important global health threats. According to the International Diabetes Federation, there were 537 million people with diabetes in 2021, which is expected to increase to 784 million by 20451. Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a serious complication of diabetes, with an incidence of more than 25% in diabetic patients. It is estimated that 40% of diabetic patients will develop DKD in their lifetime2. Studies have shown that DKD accounts for 44.5% of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in developed countries. DKD requires dialysis or kidney transplantation in the end-stage and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)3, although the current treatment regimens for DKD have made great progress in delaying the development of the disease, the prevalence of DKD is still increasing, and the related mortality has not decreased4. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of the risk factors related to the progression of DKD is helpful to establish effective prevention and treatment measures to prevent the occurrence and progression of DKD in clinical practice.

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial, recurrent, and difficult-to-treat chronic disease. The global prevalence of obesity has been increasing for decades, which has become an increasingly serious public health problem5, and it has been shown that obesity is an important risk factor for diabetes and kidney disease6,7,8,9,10. Body mass index (BMI) is a widely used index to measure obesity in the general population, but previous studies have shown that BMI is not a good predictor of chronic kidney disease (CKD)10,11, and BMI is not an accurate indicator of body fat because it is affected by gender, age, race, and muscle mass12. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are accurate and reliable for measuring fat, these machine-based measurements are too costly to be widely adopted in clinical practice. Because of this, the new obesity index, calculated based on BMI and waist circumference (WC), as well as laboratory parameters such as triacylglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), the visceral adiposity index (VAI) was proposed by Amato et al.13. It has been proven that VAI is a reliable indicator of visceral fat accumulation and dysfunction in adipose tissue14,15 and is significantly related to the occurrence of cardiovascular disease13,16,17,18, metabolic syndrome (MS)19,20,21 and some tumors22,23. Meanwhile, many studies have confirmed that VAI has a positive predictive value for diabetes24,25,26. Although some studies have investigated the association between VAI and CKD27,28,29,30,31, there are also individual studies showing that VAI is associated with the risk of composite renal disease outcomes in diabetic patients in the Chinese population32,33. However, to our knowledge, no study has evaluated the association between VAI and the incidence of DKD in the entire adult population with diabetes in the United States, and the strength of the association is unknown. Therefore, by analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), we investigated the strength of the association between the incidence of DKD and VAI in American adults with diabetes to provide a reference for the prevention of DKD in the diabetic population.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

Data were obtained from the NHANES survey published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which was designed and conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The survey sampled the US population using a cross-sectional, stratified, multistage probability method and provided nationally representative health and nutrition statistics on the US non-institutionalized civilian population. For more detailed information about the NHANES, can visit https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.The NHANES study has been approved by the US NCHS Ethics Review Board, and all participants in the study provided informed consent. In addition, we confirm that all methods employed in this study have been conducted strictly with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

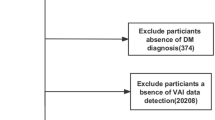

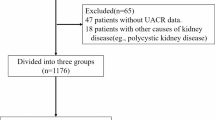

Eligible patients with diabetes who were 18 years of age or older and had complete measurements needed to calculate VAI and to determine the presence or absence of DKD were eligible for inclusion in this study, which included data from six NHANES cycles from 2007 to 2018. In the end, excluding those who were pregnant and those who lacked the necessary measurements, a total of 2508 participants were enrolled in the study. The flow chart of participant selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Definition of the VAI、diabetes and DKD

According to gender, the formula of VAI is different. For males VAI = [WC/(39.68 + (1.88 × BMI))] × (TG/1.03) × (1.31/HDL-C); for females VAI = [WC/(36.58 + (1.89 × BMI))] × (TG/0.81) × (1.52/ HDL-C)13.BMI and WC were measured at physical examination, TG and HDL-C values wer-e available in the laboratory data section, and TG and HDL-C were measured in mmol/L and WC in cm.

According to American Diabetes Association criteria and previous studies, diabetes was diagnosed by (1) previously reported diagnosis by medical professionals, or (2) fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or (3) glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5 mmol/L, or (4) current treatment for diabetes34. The ACR was calculated from the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation35. ACR ≥ 30 mg/g and/or eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 was used to diagnose DKD in diabetic patients36.

Covariates

Based on previous research, the following potential covariates were considered: Age, gender, race, education level, marital status, poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), BMI, presence of hypertension, presence of cardiovascular disease, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, serum uric acid (SUA) level, and blood total cholesterol (TC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

Among these covariates, race was categorized into the following five groups: Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other races (including multiracial). Education level was categorized as below high school, high school graduate /GED or equivalent, and college or above. Marital status was categorized as married/living with a partner, unmarried, and separated from a partner (including widowed/divorced/separated). The PIR classification method divides household income by the federal poverty line for the survey year and adjusts household size to be < 1.30 (low income), 1.30–2.99 (middle income), and ≥ 3.00 (high income)37. BMI is calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height (m2), and according to the World Health Organization criteria, participants were classified into BMI < 25 kg/m2, 25–29.9 kg/m2, and ≥ 30 kg/m2, corresponding to normal weight, overweight, and obesity38. Hypertension was defined as mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg after repeated examination by a physician39, or self-reported current use of antihypertensive medications. The presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and so on, was obtained from participants' self-reports in the medical status questionnaire. Based on smoking status, individuals were classified as never smokers (lifetime smokers < 100 cigarettes, current nonsmokers), former smokers (lifetime smokers ≧ 100 cigarettes, current nonsmokers), and current smokers. Based on alcohol consumption, anyone who had consumed at least 12 drinks in the previous 12 months was considered a drinker40. The physical activity level was divided into three groups according to the World Health Organization guidelines for physical activity status: vigorous/moderate intensity, light intensity, and never exercise41,42.

Statistical analysis

In order to obtain nationally representative results, this study performed weighted analyses according to the guidelines of NHANES. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The differences in baseline characteristics between the non-DKD group and the DKD group of diabetic patients were compared using weighted t-tests (continuous variables) or weighted chi-square tests (categorical variables). When VAI was considered as a categorical variable, it was divided into three groups, P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The weighted univariate logistic regression model (model 1) and multivariate logistic regression model (models 2 and 3) were used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the association between VAI level and DKD. Covariates were not adjusted in Model 1 and adjustments were made for age, sex, and race in Model 2. In Model 3, age, gender, race, education level, marital status, PIR, BMI, ALT, AST, TC, BUN, SUA, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, presence of hypertension, and cardiovascular disease were adjusted. To further identify potential effect moderators and explore the association between VAI levels and DKD, subgroup analyses were performed according to age, gender, race, marital status, PIR, BMI, smoking status, physical activity level, presence of cardiovascular disease and hypertension. To examine the heterogeneity of associations across subgroups, an interaction analysis was also included. Missing values for these variables were grouped using the patterns for categorical variables or filled in with the medians for continuous variables. Data analysis was performed using spss27.0, StataMP16, and R statistical software.

Ethical approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The baseline characteristics of DKD and non-DKD subjects are shown in Table 1. A total of 2508 diabetic patients were involved in this study, with an average age of 58.76 years, of which 53.25% were male and 46.75% were female. In our study, 945 (37.68%) diabetic patients were classified as having DKD. There were significant differences in age, gender, race, marital status, education level, poverty-to-income ratio, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, VAI, TC, ALT, AST, BUN, and SUA levels between the DKD and non-DKD groups (all p < 0.001). Compared with non-DKD participants, DKD participants tended to be older, had a high school education or less, were more likely to be never physically active, and generally had hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and higher levels of VAI, BUN, and SUA. Although males accounted for a higher proportion of DKD patients in this study, male participants had more non-DKD patients than DKD patients, which was contrary to the trend of female participants. Among the three VAI levels, the highest tertile array Q3 (> 2.65) had the highest incidence of DKD, and as with the middle tertile Q2 (1.45–2.65), the proportion of patients with DKD was higher than that of non-DKD, which was opposite to the lowest tertile Q1 (< 1.45). In terms of race, the total proportion of non-Hispanic white participants was the highest, followed by non-Hispanic black participants, but the proportion of DKD patients was higher in non-Hispanic white participants than non-DKD patients, while the opposite was true for non-Hispanic black participants. In terms of marital status, the proportion of married/living with a partner was the highest, and the proportion of non-DKD participants was higher than that of DKD patients, while the proportion of DKD patients who were separated from their partners was significantly higher than that of non-DKD participants. Although the non-DKD group had slightly higher PIR and BMI levels than the DKD group, the proportion of patients with DKD was higher in those with PIR < 3, BMI < 25.0 kg/m2, and BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2. In the smoking group, the proportion of never-smokers was the highest, and the proportion of non-DKD patients was higher than that of DKD patients, which was contrary to the former smoking group. In the alcohol group, low drinkers had a higher proportion of DKD patients than non-DKD patients. In addition, TC, ALT, and AST levels were higher in the non-DKD group than in the DKD group.

VAI is associated with an increased incidence of DKD

We transformed VAI into a three-category variable and created a number of models to assess the independent effect between VAI and the incidence of DKD in diabetic patients. Table 2 shows that, after controlling for many confounding variables, increased VAI levels were associated with increased risk of DKD, a relationship that was significant in both our base model and the least adjusted model. In model 1, subjects in the highest tertile of VAI had a 39.0% increased risk of DKD compared with those in the lowest tertile (OR = 1.390, 95% CI 1.388, 1.393). In model 2, the risk was significantly increased by 66.1% (OR = 1.661, 95% CI 1.658, 1.665), and the positive correlation between VAI and DKD incidence remained stable in fully adjusted model 3 (OR = 1.359, 95% CI 1.355, 1.362). According to univariate logistic analysis, VAI was a risk factor for DKD (OR = 1.050, 95% CI 1.049, 1.050, p < 0.001, Table 3), and age, gender, race, marital status, education level, PIR, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, TC, ALT, AST, BUN, and SUA were also significantly associated with the incidence of DKD in the weighted univariate analysis (p < 0.001, Table 3).

Female participants were 12.1% more likely than male participants to have DKD (p < 0.001). Compared with Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, non-Hispanic white person, and non-Hispanic black person were 38.0%, 34.1%, and 32.3% less likely to have DKD respectively (all p < 0.001). Compared with married/living with a partner, unmarried participants were 6.2% less likely to have DKD, whereas those separated from a partner were 27.3% more likely (both p < 0.001). Participants with a high school education were 9.0% more likely to have DKD than those who did not complete high school, whereas those with a college degree or higher were 5.8% less likely (both p < 0.001). Compared with diabetic patients who never smoked, the likelihood of DKD was respectively increased by 13.6% and 32.3% in former and current smokers (both p < 0.001). In the exercise group, those who exercised lightly were 9.1% less likely to have DKD (p < 0.001), and 0.3% higher in moderate/vigorous exercise participants (p < 0.001). Compared with participants without hypertension or cardiovascular disease, the odds of DKD in patients with hypertension or cardiovascular disease were respectively 1.416 and 1.213 times higher (both p < 0.001). For each unit increase in age, BMI, TC, BUN, and SUA, the odds of DKD increased respectively by 2.2%, 0.4%, 0.2%, 10.4%, and 15.8% (all p < 0.001). For each unit increase in PIR, ALT, and AST, the odds of DKD decreased by 13.9% and 0.1% respectively (all p < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

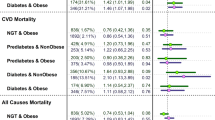

The results of our subgroup analyses showed inconsistent associations between VAI levels and DKD (Fig. 2). For the subgroups stratified by age, VAI was significantly associated wit-h the incidence of DKD in each subgroup (all p < 0.05), while others were only found in males(OR = 1.043, 95% CI 1.010, 1.080), participants without cardiovascular disease(OR = 1.038, 95% CI 1.011, 1.069), patients with hypertension(OR = 1.054, 95% CI 1.021, 1.090), unmarried participants(OR = 1.153, 95% CI 1.036, 1.294), PIR < 1.30(OR = 1.049, 95% CI 1.010, 1.094), participants with P-IR ≧ 3 (OR = 1.085, 95% CI 1.021, 1.160), BMI ≧ 30 kg/m2 (OR = 1.050, 95% CI 1.016, 1.091), former smokers (OR = 1.060, 95% CI 1.011, 1.117), never exercised (OR = 1.033, 95% CI 1.004, 1.067), non-Hispanic white people(OR = 1.055, 95% CI 1.010, 1.106) and non-Hispanic black people(OR = 1.129, 95% CI 1.033, 1.258). The interaction test showed that only race had a significant effect on the relationship (P = 0.039), indicating that age, sex, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, marital st-atus, PIR, BMI, smoking status, and physical activity level had no significant dependence on the positive correlation except for race (all interactions p > 0.05, Fig. 2).

Discussion

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 2508 diabetic patients from the NHANES database and found that VAI levels were higher in these diabetic patients with DKD than in non-DKD participants. Most importantly, our findings highlighted VAI as a risk factor for the development of DKD by constructing a multivariate logistic model. This association persisted even after adjustment for all confounding factors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show a relationship between VAI and DKD in diabetic patients in a US population.

Previous studies have shown that obesity is an important risk factor for renal function decline, and BMI, widely used to measure obesity in the general population, has been shown to be a poor predictor of kidney disease43. Our study showed that the probability of DKD increased respectively by 5% and 0.4% for each unit increase in VAI and BMI(Table 3), which also proved the higher sensitivity of VAI in predicting the occurrence of DKD compared with BMI, which was consistent with previous cross-sectional studies conducted in China44, therefore, we recommend that health care providers use VAI instead of traditional obesity index when screening the risk of DKD in diabetic patients.

In our subgroup analysis, when grouped by gender, the significant relationship between VAI and DKD incidence was only significant in men, which was similar in other studies from different regions. A study of 6693 non-diabetic participants conducted in Iran observed that VAI appeared to be an independent predictor of reduced renal function only in men45; A cross-sectional study in Korea showed that VAI was positively correlated with the incidence of CKD only in Korean men, but not in women46. However, some studies also provided inconsistent evidence, one study in rural northeast China showed that VAI had good predictive value in the incidence of CKD in women47; A study of 400 individuals aged 50–90 years, also conducted in China, also reported a strong association between VAI and the occurrence of CKD in middle-aged and elderly women in Taiwan, China48; In addition, a longitudinal study conducted in Japan showed that VAI can predict CKD in both men and women29. Our study in a U.S. diabetic population, like the above studies, highlighted the negative effect of VAI on the decline of renal function, but we believe that factors such as region, race, sample size, and study design may account for the different results reported in these studies with respect to sex. Differences in sex hormones and fat distribution between men and women may also be part of the reason31, and the mechanism behind the gender difference needs to be further studied. In addition, subgroup analyses by race showed that VAI was significantly associated with DKD only among non-Hispanic white people and non-Hispanic black people, and interaction tests showed that race had a significant effect on this relationship. As compared with Mexican Americans, black person have a 1.8% higher risk of DKD than white person(Table 3), and the risk of DKD per unit increase in VAI is more than twice as high in black person as in white person (Fig. 2). Therefore, we boldly assume that DKD is more common in black people with diabetes than in white people, and black race may have a reinforcing effect on the positive correlation between VAI and DKD, but no study has yet proven this idea, so further studies are needed to confirm this. A more promising result of this study is that in the subgroup analysis by age, for each unit increase in VAI, the probability of DKD in diabetic patients younger than 65 years old was 1.8% higher than that in those 65 years and older. Increasing VAI has been shown to increase cardiometabolic risk13, stroke risk49, etc. But younger age is known to be a protective factor for these diseases. Therefore, the predictive effect of VAI on DKD may have higher sensitivity and specificity in young individuals, and strict control of VAI in young diabetic patients can effectively prevent the occurrence of DKD. Currently, only one study mentioned that VAI may be better in predicting the occurrence of kidney stones in young individuals50. Wherefore, further large-scale prospective studies are needed to confirm the causality of this conclusion.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses also confirmed that some confounding factors were predisposing factors for the occurrence of DKD in diabetic patients. In our study, age, separation from partner, lower education, obesity, smoking, lack of exercise, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease may all contribute to the increased risk of DKD in diabetic patients, and these risk factors are generally consistent with those described in previous studies51,52. In univariate logistic regression analysis, we found that diabetic patients with high SUA levels were at increased risk of developing DKD, suggesting that increased SUA concentrations are a risk factor for the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy, which is consistent with the results of previous prospective studies53,54. The underlying mechanism may be that elevated SUA levels promote endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress at the cellular and tissue levels, triggering renal inflammation and fibrosis, and then promoting renal injury in diabetic patients55,56,57. Furthermore, elevated SUA concentrations have been shown to induce tubulointerstitial injury, and SUA levels have a potential role in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)-mediated tubular injury. Although tubular injury appears to resolve after 3 months, recurrent episodes of DKA may lead to irreversible tubular lesions that could accelerate the progression of DKD58. Therefore, reducing SUA levels in diabetic patients may be another potential way to prevent the occurrence and progression of DKD. As for the sex difference in the incidence of DKD in this study (Table 3), it may be related to gene expression and changes in diabetes-induced hormone levels, making kidney damage more severe in women than in men59,60. In the future, more research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of sensitivity to kidney injury in women with diabetes. This may help us to develop sex-specific treatment strategies for DKD. Notably, our results showed that among the three BMI groups, only in the second category (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) of diabetes was the proportion of patients with DKD lower than those without DKD (Table 1), this conclusion was also demonstrated in a previous cohort study43, suggesting that controlling BMI at an appropriate level in diabetic patients may effectively prevent the occurrence of DKD.

The mechanism of the association between VAI and DKD may be related to inflammation and hemodynamic changes, and so on61.In the state of central obesity, adipocytes produce excessive proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), and reduce the production of anti-inflammatory adipokines. At the same time, adipose tissue macrophages infiltrate and produce excessive TNF-α, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation and subsequent kidney injury62,63. In addition, this accumulation of obesity may also activate the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), cause hypertension and increase insulin resistance, resulting in kidney damage64. Visceral obesity may also cause changes in renal hemodynamics, increase the glomerular filtration rate relative to the effective renal plasma flow, which increases the filtration fraction, and ultimately lead to podocyte loss and glomerular sclerosing injury, thereby substantially reducing renal function65. Excessive accumulation of perirenal fat in the renal sinus can also block renal parenchyma and blood vessels, promote sodium absorption, and increase blood pressure, at the same time, excessive perirenal fat encases the kidney and increases renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure, causing renin secretion and glomerular filtration changes, which eventually lead to the occurrence of kidney disease66. The study of these mechanisms also makes VAI a positive potential for therapeutic use in DKD. However, it is important to note that the pathophysiologic mechanisms of the association between obesity and DKD may be bidirectional. Not only can obesity lead to the occurrence of DKD through the above mechanisms, but DKD can also cause obesity by altering metabolic pathways in the body and causing changes in adipose tissue. For example, insulin resistance in patients with DKD can inhibit the catabolism of Branched-chain amino acids by reducing the enzymatic activity of the branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, which is a plausible cause of obesity67. Another study showed that patients with DKD underwent significant changes in lipid metabolism, such as a significant increase in the expression of cholesterol uptake genes and a significant decrease in genes regulating cholesterol efflux, which also contributes to the development of obesity68. More studies are needed to confirm this bidirectional association between obesity and DKD in the future.

This study has the following strengths. First, the study participants of NHANES are representative of American adults, and the sample selection and sample size are representative and adequate; Second, we adjusted for confounding variables to reduce bias and performed subgroup analyses, which makes our findings more robust and generalizable to a wider range of individuals. However, the limitations of our study should also be noted. Our study was a cross-sectional study, so we could not assess the causal relationship between VAI and DKD, which requires a prospective study with a larger sample size to address this question; Second, although we controlled for some potential covariates, we could not completely rule out the influence of other confounding variables, such as the use of other drugs on the test results; In addition, some of our data were obtained from patient self-reports, which cannot avoid the influence of recall bias. But despite these limitations, the standardized and rigorous data collection procedures in the NHANES also ensured the reliability of this study.

Conclusion

In our study, we demonstrate that elevated VAI levels are strongly associated with the development of DKD in a representative cohort of US adults with diabetes and that VAI may be a superior indicator for predicting the development of DKD. This is of great significance in preventing the occurrence and progression of DKD in diabetic patients and even guiding the treatment of DKD in clinical practice. However, the association between VAI and DKD may show differences in different populations, where the effects of gender, race, and age need to be thoroughly considered. Further confirmation by large-scale prospective studies is still needed to validate our findings.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm

References

de Boer, I. H. et al. Diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: a consensus report by the american diabetes association (ADA) and kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care 45(12), 3075–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.08.012 (2022).

Afkarian, M. et al. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. Jama 316(6), 602–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10924 (2016).

Collins, A. J. et al. US renal data system 2010 annual data report. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 57(1), A8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.007 (2011).

Thomas, Merlin C et al. “Diabetic kidney disease.” Nature reviews. Disease primers vol. 1 15018. 30 Jul. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.18

Lavie, C. J., McAuley, P. A., Church, T. S., Milani, R. V. & Blair, S. N. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J. Am. College Cardiol. 63(14), 1345–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022 (2014).

Boles, A., Kandimalla, R. & Reddy, P. H. Dynamics of diabetes and obesity: Epidemiological perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863(5), 1026–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.01.016 (2017).

Verma, S. & Hussain, M. E. Obesity and diabetes: An update. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 11(1), 73–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2016.06.017 (2017).

Fox, C. S. et al. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. JAMA 291(7), 844–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.7.84 (2004).

Câmara, N. O., Iseki, K., Kramer, H., Liu, Z. H. & Sharma, K. Kidney disease and obesity: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13(3), 181–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2016.191 (2017).

Hall, J. E., do Carmo, J. M., da Silva, A. A., Wang, Z. & Hall, M. E. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: Mechanistic links. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15(6), 367–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0145-4 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. A novel visceral adiposity index for prediction of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in Chinese adults: A 5-year prospective study. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 13784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14251-w (2017).

Agarwal, R., Bills, J. E. & Light, R. P. Diagnosing obesity by body mass index in chronic kidney disease: An explanation for the “obesity paradox?”. Hypertension 56(5), 893–900. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160747 (2010).

Amato, M. C. et al. Visceral adiposity index: A reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes care 33(4), 920–2. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1825 (2010).

Li, R. et al. Visceral adiposity index, lipid accumulation product and intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 7951. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07811-7 (2017).

Roriz, A. K. et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of anthropometric clinical indicators of visceral fat in adults and elderly. PloS one. 9(7), e103499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103499 (2014).

Qiao, T. et al. Association between abdominal obesity indices and risk of cardiovascular events in Chinese populations with type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21(1), 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01670-x (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Visceral adiposity index and the risk of heart failure, late-life cardiac structure, and function in ARIC study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 30(12), 1182–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwad099 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Visceral adiposity index is associated with arterial stiffness in hypertensive adults with normal-weight: The china H-type hypertension registry study. Nutr. Metab. 18, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-021-00617-5 (2021).

Vizzuso, S. et al. Visceral adiposity index (VAI) in children and adolescents with obesity: No association with daily energy intake but promising tool to identify metabolic syndrome (MetS). Nutrients 13(2), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020413 (2021).

López-González, A. A. et al. The CUN-BAE, Deurenberg fat mass, and visceral adiposity index as confident anthropometric indices for early detection of metabolic syndrome components in adults. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15486. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19343-w (2022).

Vega-Cárdenas, M., Teran-Garcia, M., Vargas-Morales, J. M., Padrón-Salas, A. & Aradillas-García, C. Visceral adiposity index is a better predictor to discriminate metabolic syndrome than other classical adiposity indices among young adults. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 35(2), e23818. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23818 (2023).

Cardoso-Peña, E. et al. Visceral adiposity index in breast cancer survivors: A case-control study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020(1), 8874916 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Associations between Chinese visceral adiposity index and risks of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A population-based cohort study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26(4), 1264–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15424 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. The visceral adiposity index and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: A national cohort analysis. Diabetes/metab. Res. Rev. 38(3), e3507. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3507 (2022).

Tsou, M. T. et al. Visceral adiposity index outperforms conventional anthropometric assessments as predictor of diabetes mellitus in elderly Chinese: A population-based study. Nutr. Metab. 18, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-021-00608-6 (2021).

Koloverou, E. et al. Visceral adiposity index outperforms common anthropometric indices in predicting 10-year diabetes risk: Results from the ATTICA study. Diabetes/metab. Res. Rev. 35(6), e3161. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3161 (2019).

Lei, L. et al. The association between visceral adiposity index and worsening renal function in the elderly. Front. Nutr. 9, 861801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.861801 (2022).

Kim, B., Kim, G. M. & Oh, S. Use of the visceral adiposity index as an indicator of chronic kidney disease in older adults: Comparison with body mass index. J. Clin. Med. 11(21), 6297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216297 (2022).

Bamba, R. et al. The visceral adiposity index is a predictor of incident chronic kidney disease: A population-based longitudinal study. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 45(3), 407–18. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506461 (2020).

Jin, J. et al. Novel Asian-specific visceral adiposity indices are associated with chronic kidney disease in Korean adults. Diabetes Metab. J. 47(3), 426–36. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0099 (2023).

Peng, W., Han, M. & Xu, G. The association between visceral adiposity index and chronic kidney disease in the elderly: A cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 2011–2018. Prev. Med. Rep. 35, 102306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102306 (2023).

Zhou, C. et al. Associations between visceral adiposity index and incident nephropathy outcomes in diabetic patients: Insights from the ACCORD trial. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 39(3), e3602. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3602 (2023).

Sun, Z. et al. Correlation between the variability of different obesity indices and diabetic kidney disease: A retrospective cohort study based on populations in Taiwan. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 16, 2791–802. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S425198 (2023).

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes care 44(1), S15-33. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-S002 (2021).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Int. Med. 150(9), 604–12. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

de Boer, I. H. et al. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. Jama 305(24), 2532–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.861 (2011).

O’Hearn, M., Lauren, B. N., Wong, J. B., Kim, D. D. & Mozaffarian, D. Trends and disparities in cardiometabolic health among US adults, 1999–2018. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80(2), 138–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.046 (2022).

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 363(9403), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 (2004).

Unger, T. et al. 2020 International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension 75(6), 1334–57. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. The associations of plant protein intake with all-cause mortality in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 67(3), 423–30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.10.018 (2016).

Burtscher, J., Millet, G. P. & Burtscher, M. Pushing the limits of strength training. Am. J. Prev. Med. 64(1), 145–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2023).

Pratt, M. What’s new in the 2020 World Health Organization guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior?. J. Sport Health Sci. 10(3), 288–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.02.004 (2021).

Lu, J. L. et al. Age and association of body mass index with loss of kidney function and mortality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3(9), 704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00128-X (2015).

Wan, H. et al. Associations between abdominal obesity indices and diabetic complications: Chinese visceral adiposity index and neck circumference. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-020-01095-4 (2020).

Mousapour, P. et al. Predictive performance of lipid accumulation product and visceral adiposity index for renal function decline in non-diabetic adults an year follow-up. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 24(3), 225–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01813-7 (2020).

Seong, J. M. et al. Gender difference in the association of chronic kidney disease with visceral adiposity index and lipid accumulation product index in Korean adults: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 53, 1417–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02735-0 (2021).

Dai, D. et al. Visceral adiposity index and lipid accumulation product index: two alternate body indices to identify chronic kidney disease among the rural population in Northeast China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13(12), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13121231 (2016).

Chen, I. J. et al. Gender differences in the association between obesity indices and chronic kidney disease among middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese population: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol. 12, 737586. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.737586 (2021).

Chen, Q., Zhang, Z., Luo, N. & Qi, Y. Elevated visceral adiposity index is associated with increased stroke prevalence and earlier age at first stroke onset: Based on a national cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1086936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1086936 (2023).

Hou, B. et al. Is the visceral adiposity index a potential indicator for the risk of kidney stones?. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1065520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1065520 (2022).

Qin, Z., Chen, X., Sun, J. & Jiang, L. The association between visceral adiposity index and decreased renal function: A population-based study. Front. Nutr. 10, 1076301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1076301 (2023).

Bonner, R., Albajrami, O., Hudspeth, J. & Upadhyay, A. Diabetic kidney disease. Prim. Care Clin. Office Pract. 47(4), 645–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2020.08.004 (2020).

Ficociello, L. H. et al. High-normal serum uric acid increases risk of early progressive renal function loss in type 1 diabetes: Results of a 6-year follow-up. Diabetes care 33(6), 1337–43. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0227 (2010).

Zoppini, G. et al. Serum uric acid levels and incident chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and preserved kidney function. Diabetes care 35(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1346 (2012).

Kang, D. H. et al. A role for uric acid in the progression of renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13(12), 2888–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.asn.0000034910.58454.fd (2002).

Komers, R., Xu, B., Schneider, J. & Oyama, T. T. Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibition with febuxostat on the development of nephropathy in experimental type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173(17), 2573–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13527 (2016).

Hu, Q. H., Zhang, X., Pan, Y., Li, Y. C. & Kong, L. D. Allopurinol, quercetin and rutin ameliorate renal NLRP3 inflammasome activation and lipid accumulation in fructose-fed rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84(1), 113–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.005 (2012).

Piani, F. et al. Tubular injury in diabetic ketoacidosis: Results from the diabetic kidney alarm study. Pediatric diabetes 22(7), 1031–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13259 (2021).

Giandalia, A. et al. Gender differences in diabetic kidney disease: Focus on hormonal, genetic and clinical factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(11), 5808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115808 (2021).

Lane, P. H. Diabetic kidney disease: Impact of puberty. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283(4), F589-600. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00368.2001 (2002).

Chen, S. et al. Central obesity, C-reactive protein and chronic kidney disease: A community-based cross-sectional study in southern China. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 37(4–5), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355718 (2013).

Wahba, I. M. & Mak, R. H. Obesity and obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome: Mechanistic links to chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2(3), 550–62. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.04071206 (2007).

Zhang, X. L., Topley, N., Ito, T. & Phillips, A. Interleukin-6 regulation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor compartmentalization and turnover enhances TGF-β1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 280(13), 12239–45. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M413284200 (2005).

Rüster, C. & Wolf, G. The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in obesity-related renal diseases. Semin. Nephrol. 33(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.12.002 (2013).

Chagnac, A., Zingerman, B., Rozen-Zvi, B. & Herman-Edelstein, M. Consequences of glomerular hyperfiltration: The role of physical forces in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease in diabetes and obesity. Nephron 143(1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499486 (2019).

Huang, N. et al. Novel insight into perirenal adipose tissue: A neglected adipose depot linking cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease. World J. Diabetes 11(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v11.i4.115 (2020).

Melena, I. et al. Aminoaciduria and metabolic dysregulation during diabetic ketoacidosis: Results from the diabetic kidney alarm (DKA) study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 36(6), 108203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2022.108203 (2022).

Ducasa, G. M., Mitrofanova, A. & Fornoni, A. Crosstalk between lipids and mitochondria in diabetic kidney disease. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 19, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1263-x (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.: software, data analysis, and writing—original draft. G.W.: writing—original draft, formal analysis, and methodology. J.Z., W.J., S.W., W.W., S.P., and C.P.: data analysis. W.S.: conceptualization, and writing—reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Wang, G., Zhang, J. et al. Association between visceral adiposity index and incidence of diabetic kidney disease in adults with diabetes in the United States. Sci Rep 14, 17957 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69034-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69034-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Visceral fat area loss reduces 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in Chinese population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Development and validation of a novel glucolipid metabolism-related nomogram to enhance the predictive performance for osteoporosis complications in prediabetic and diabetic patients

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Visceral adiposity index, premature mortality, and life expectancy in US adults

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)