Abstract

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) is a salivary gland neoplasm that infrequently appears in the sinonasal region. The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcome and clinicopathological parameters of sinonasal AdCC. A retrospective analysis was conducted on all cases of AdCC affecting the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses between 2000 and 2018 at the University Hospital Zurich. Tumor material was examined for morphological features and analyzed for molecular alterations. A total of 14 patients were included. Mean age at presentation was 57.7 years. Sequencing revealed MYB::NFIB gene fusion in 11/12 analyzable cases. Poor prognostic factors were solid variant (p < 0.001), histopathological high-grade transformation (p < 0.001), and tumor involvement of the sphenoid sinus (p = 0.02). The median recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS were 5.2 years and 11.3 years. The RFS rates at 1-, 5-, and 10-year were 100%, 53.8%, and 23.1%. The OS rates at 1-, 5-, and 10- years were 100%, 91.7%, and 62.9%, respectively. In Conclusion, the solid variant (solid portion > 30%), high-grade transformation, and sphenoid sinus involvement are negative prognostic factors for sinonasal AdCC. A high prevalence of MYB::NFIB gene fusion may help to correctly classify diagnostically challenging (e.g. metatypical) cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) is a rare malignant epithelial neoplasm that arises primarily from the major salivary glands but can also occur in other sites such as the minor salivary glands of the oral cavity and the sinonasal tract (comprising the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses), the skull base as well as the nasopharynx1. It is known for its slow, but aggressive growth, perineural invasion2,3,4, high frequency of recurrence5, and poor long-term prognosis6,7. Sinonasal AdCC, has a worse prognosis due to difficulty in achieving clear margins and proximity to vital structures8. The rate of local invasion is significantly higher in the paranasal sinus than in other anatomic sites, resulting in an advanced tumor stage at diagnosis9,10,11. Symptoms at initial presentation of sinonasal AdCC typically include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, facial pain, or dysesthesia9,12. The standard diagnostic work-up for AdCC is a combination of state-of-the-art cross-sectional imaging studies and hybrid whole-body PET imaging1, followed by tumor exploration and biopsy under general anesthesia including a thorough histopathological analysis13. The first-line therapy for AdCC is typically surgical resection, often followed by radiotherapy14,15.

Predictors affecting survival in sinonasal AdCC include age, comorbidity status, and advanced tumor stage16. Surgical intervention is associated with improved survival, while the role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy requires further investigation16.

Histologically, AdCC is a basaloid tumor composed of epithelial and myoepithelial cells, which typically exhibits a mixed growth pattern of tubular, cribriform, and/or solid structures17,18,19. The solid variant is recognized as a risk factor and is often linked to aggressive behavior and poor outcomes1,20,21. Three grading systems for AdCC are currently proposed, including the Spiro22, Perzin/Szanto23,24, and van Weert system25. The Spiro and Perzin/Szanto gradings are based on the proportion of the solid tumor component (> 50%, > 30%). The van Weert system, scores the mere presence of a solid growth pattern. Other pathological prognostic factors include a high mitotic index and high-grade transformation (defined as comedo-type tumor necrosis, frequent mitoses, marked nuclear atypia and desmoplastic stromal reaction)26,27. In addition to these subtypes, AdCC may also exhibit a metatypical variant, predominantly found in the sinonasal tract. It is characterized by trabecular architecture, macrocystic growth, and squamous, as well as sebaceous differentiation28,29. However, the prognostic value of this new subtype is not fully understood30.

The diagnosis of AdCC is not only challenging due to its morphological diversity, but also due to its similarity to other tumors, such as Human Papillomavirus-Related Multiphenotypic Sinonasal Carcinoma (HMSC), formerly known as Human Papillomavirus-Related Carcinoma with Adenoid Cystic-like Features31,32. Additionally, over the past decade, several new and distinct histopathological entities of sinonasal cancer types have been identified and new subtypes continue to emerge33,34. Considering these challenges, a clinicopathological retrospective study on sinonasal AdCC has been conducted to determine its outcome and prognostic factors, with a particular focus on the histopathological and molecular features.

Materials and methods

Study design

A retrospective analysis was conducted on all cases with clinical diagnosis of AdCC affecting the nasal cavity, the paranasal sinuses, or tumor invasion in these regions that were treated between 2000 and 2018 at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at the University Hospital of Zurich (Switzerland). Clinical data were obtained from the hospital records. This study received approval from the ethical committee of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland (approval number: BASEC 2020-01663). Written informed consent has been obtained from patients included from 2016 onwards. For older samples/data, a informed consent waiver was granted by the ethics committee. No patient with documented refusal to participate was included.

Pathological work-up

All patients’ diagnoses were confirmed by an experienced head and neck pathologist (NJR). In unusual cases, additional p16 staining, and HPV high-risk in situ hybridization or HPV DNA PCR was performed to identify the morphological mimicker HMSC. Tumor material of included cases was tested for molecular alterations using our updated and validated version 2 of the “SalvGlandDx” Next Generation Sequencing panel as described previously35. In brief, the RNA-based panel covers relevant fusion genes, including MYB and MYBL1, and is able to detect the canonical (MYB::NFIB, MYBL1::NFIB), and novel/unusual fusions of these genes. In addition, this updated version of the “SalvGlandDx” panel includes NOTCH1. All specimens were examined for morphology and perineural/lymphovascular invasion. In accordance with the grading system proposed by Szanto, the solid variant was defined as comprising more than 30% of the tumor24. In addition, the mitotic index (> 5 mitoses per 10 high power fields, 1 HPF = 0.25 mm2) was determined.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the baseline characteristics of the included patients. To evaluate the association of various clinicopathological factors with OS and RFS, a univariate analysis was performed. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated to assess the survival outcomes. 95% confidence intervals (= CI) were calculated to account for the precision of the estimated effects. Prognostic factors were analyzed using the log-rank test, allowing for the comparison of survival curves. Statistical significance was assessed using a significance level of p < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant association. Median survival or follow-up time was estimated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier function. The statistical analyses are considered exploratory, no adjustment for multiple testing was done. All analyses were computed using R (version 4.2.2.). This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Ethics approval

We declare that our research was conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines. This study received approval from the ethical committee of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland (approval number: BASEC 2020-01663).

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

All samples analyzed were obtained between 2000 and 2018. A total number of n = 16 cases with clinical diagnosis of AdCC were reevaluated histologically, while two cases were (re)classified and excluded as HMSC, one of which had been published in a previous work36. Thus, our series included n = 14 patients with confirmed histopathological diagnosis of AdCC. For three patients, the date of diagnosis and the initiation of therapy occurred before the year 2000. The study comprised eight women (57.1%) and six men (42.9%). The mean age at diagnosis was 57.7 (± 16.1) years, ranging from 30 to 85 years. Presenting symptoms were reported in n = 13 (92.9%) patients. The tumor epicenter was mostly located in the nasal cavity (n = 6, 43%). In all patients except one (92.9%), multiple anatomic subsites were involved. The most frequently affected subsites were the nasal cavity (n = 9, 64.3%) and the paranasal sinuses (n = 8, 57.1%), whereby the maxillary and sphenoid sinus were most affected, each with five cases (35.7%). Invasion into adjacent structures was observed at the skull base (n = 7, 50%), the pterygopalatine fossa (n = 4, 28.6%), and the orbital cavity (n = 3, 21.4%). Clinical staging information was available for all patients except one (n = 13, 92.9%). 11 out of 13 patients had locally advanced tumor stage (stage IV, 84.6%)37. One patient (7.1%) showed lymph node involvement and one (7.1%) presented with distant metastasis in the lungs and brain at the time of diagnosis. Table 1 provides detailed information on patient and tumor characteristics.

Treatment characteristics

All patients were treated with a curative approach. Half of the patients (n = 7, 50%) were treated with a combination of surgery and adjuvant (n = 6, 42.9%) or neoadjuvant (n = 1, 7.1%) radiotherapy. Six patients (42.9%) underwent monotherapy, with four (28.6%) receiving radiation therapy and two (14.3%) receiving surgery. One patient (7.1%) underwent a multimodal approach consisting of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Among the 10 patients receiving surgery, 70% underwent open surgery (n = 7), and 30% of these cases involved endoscopic resection (n = 3). Data regarding tumor resection margins were limited to four patients, with an equal distribution between positive (n = 2) and negative (n = 2) margins.

Outcome

All patients except one (92.9%) achieved complete remission under first-line therapy. However, of the 13 patients with remission, all developed recurrence (92.3%), except for one patient (7.7%) with a current follow-up of 9.8 years. All relapses were local (91.7%), except for one patient (8.4%) who developed distant metastasis in the lung. Two patients had extraordinarily long recurrence-free survival (RFS) of 15.7 and 16.3 years, while all other patients experienced recurrence within 7.2 years. The median RFS was 5.2 years. Our patients’ 1-, 5-, 10-, and 20-year RFS rates were 100% (95% CI 100%), 53.8% (95% CI 32.6–89.1%), 23.1% (95% CI 8.6–62.3%), and 0% (95% CI 0–100%) respectively (Fig. 1A).

(A,B) Kaplan–Meier curves for recurrence-free survival (A: RFS) and overall survival (B: OS). The x-axis represents the time in years from the end of the initial therapy to the event of recurrence (A) or from the date of diagnosis to mortality (B).The solid line represents the estimated survival function for either RFS or OS, and the dashed lines show the 95% confidence intervals. For OS: Number at risk at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 years respectively: 14(0), 11(0), 7(2), 2(3), 1(3), and 1(3), with numbers in parentheses indicating censored cases. For RFS: Number at risk at 0, 5, 10, and 15 years respectively: 13(0), 7(0), 2(1), and 2(1), with numbers in parentheses representing censored cases.

The median follow-up time for all patients was 10.3 years. The two patients who had an especially long RFS also experienced a long follow-up time of 26.3 and 46.5 years. All other patients had a maximum follow-up time of 12.6 years. Three patients (21.4%) were lost to follow-up after 1, 2.5, and 8.6 years, all of whom had experienced major tumor progression at their last follow-up. Three patients from our series (21.4%) are still alive, with an average follow-up duration of 8.4 years. All other patients (78.6%) died with stable or progressive disease. The median OS was 11.3 years and the OS rates at 1-, 5-, 10- and 20-years were 100% (95% CI 100%), 91.7% (95% CI 77.3–100%), 62.9% (95% CI 39.5–100%) and 31.4% (95% CI 10.6–93%) respectively (Fig. 1B).

Prognostic factors

Stratifying the patients by all available prognostic factors revealed no evidence that sex was associated with survival (p = 0.3). Neither did we observe any symptoms to be indicative of poor survival. Our analysis found that the only anatomical site associated with poorer OS was the sphenoid sinus (p = 0.02). Additionally, tumors with the epicenter located within the sphenoid sinus showed a stronger association with OS (p < 0.001) compared to those just involving the sphenoid sinus. Treatment modality was not associated with survival outcomes. It should be noted that the small sample size limits the generalizability of these findings.

Molecular and histopathological work-up

At our institute, n = 16 patients were evaluated with the diagnosis of sinonasal AdCC treated between 2000 and 2018. Out of 16 cases, two (12.5%) could be reclassified as HMSC and were excluded from the study. From the remaining n = 14, two cases (14.3%) could not be sequenced due to poor RNA quality, but the morphology was typical for AdCC. Out of all analyzable cases (n = 12), MYB::NFIB gene fusion was detected in 11 cases (91.7%). No MYBL1::NFIB gene fusion or NOTCH1 alteration was detectable.

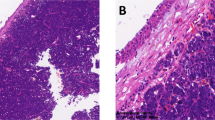

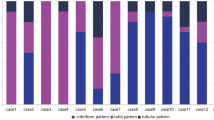

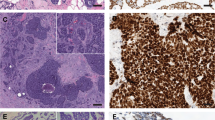

The predominant growth patterns most frequently observed among the study subjects was tubular-cribriform (n = 11, 78.6%), followed by tubular-trabecular (n = 2, 14.3%), and solid growth pattern (n = 1, 7.1%) (solid portion > 30%). Out of all cases four subjects (28.6%) had lesser proportions of solid growth (< 30%) and were therefore not classified as solid variant. Three subjects (21.4%) had areas compatible with so called metatypical AdCC, however, we did not observe squamous differentiation. Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3 provide detailed information on the histological features.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of AdCC with metatypical features: predominant tubular morphology with large cystic spaces (A). Tubular–trabecular growth pattern (B). Tubular–trabecular morphology with necrosis and solid parts < 30% (C). All cases revealed a MYB::NFIB gene fusion. The scale bar is 250 µm.

Analyzing the outcome based on pathological features, we identified that there was evidence that the solid variant (> 30% solid growth, p < 0.001) and a high-grade transformation (p < 0.001) were associated with worse OS, while other factors such as necrosis (p = 0.3), sclerosis (p = 1), cystic spaces (p = 1), or perineural (p = 0.5) /lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.5) or other growth patterns showed no evidence of association. Our investigation of whether solid parts (< 30%), are a risk factor for poor OS, yielded no evidence to suggest an association (p = 0.2). Presence of the MYB::NFIB gene fusion did not reveal evidence of an association with OS (p = 0.8). Furthermore, we revealed no evidence of a link between poor OS and metatypical morphology (p = 0.8). The extent to which some of these findings can be generalized is restricted due to the limited sample size.

Discussion

Our analysis yielded evidence that the solid variant (solid growth pattern > 30%), histopathological high-grade transformation, and tumor involvement of the sphenoid sinus were associated with poor prognosis. There was no evidence that the presence of MYB::NFIB gene fusion, metatypical morphology, perineural invasion, and the therapeutic modality, was associated with a distinct outcome.

Our analysis revealed, as in previous reports, a slight predominance of females and a mean age of around 60 years at the time of initial presentation9,11,16,38. There was a notably higher proportion of advanced local tumor stage (T4) at the time of diagnosis (84.6%), in contrast to previous reports that have indicated an incidence of approximately 45–65%11,16,39,40. Our data also showed a different distribution of tumor epicenter compared to the literature, where the maxillary sinus is reported as the most common epicenter, followed by the nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus, and sphenoid sinus11,12,16,40,41,42,43. In agreement with our results, Unsal et al. found that AdCCs originating in the nasal cavity tend to have a better prognosis, while those originating in the sphenoid have the worst11. Our patients’ prognosis, who frequently presented with advanced tumor stages at diagnosis, did not show an association with any therapeutic modality.

An international study examining the recurrence patterns of sinonasal carcinomas (mean follow-up time of 4.8 years) reported that AdCC exhibited the highest rate of recurrence beyond five years (72.2%) compared to other sinonasal tumors5. Our analysis demonstrated a significantly higher rate of 92.3%, which could potentially be attributed to our prolonged follow-up duration of 10.3 years. According to the largest retrospective study on sinonasal AdCC (n = 793) conducted so far, the 5-year OS rate was found to be 60.7%16. This finding aligns with a meta-analysis on sinonasal AdCC from 2013 that calculated a 5-year OS rate of 62%8. Our study found a 5-year OS rate of 91.7%. Some studies have reported 5-year OS rates for sinonasal AdCC between 80 and 90%44,45,46, but to our knowledge, no study has reported rates over 90%.

The pathognomonic MYB::NFIB gene fusion is a highly specific marker for AdCC and is widely accepted as the gold standard for diagnosis47. Its frequency in AdCC varies between 40 and 70%48. Although MYB::NFIB rearrangement has demonstrated efficacy in diagnosing AdCC, its prognostic value is controversial49. Two meta-analyses found no significant association between the translocation status of MYB and survival rates in AdCC patients50,51. Accordingly, we did not observe an association between the detection of this genetic alteration and poor outcomes. In our analysis, no MYBL1::NFIB gene fusion or NOTCH1 mutation was detected. Further, no recently described EWSR1::MYB or FUS::MYB fusion was detected in this cohort52. Tumors with NOTCH1 mutations define an aggressive subgroup of AdCC with a significantly higher likelihood of exhibiting a solid growth pattern, shorter RFS, and poorer OS53. These genetic alterations were also found to be more frequent in recurrent and metastatic tumors compared to primary tumors54. Given that our series included only one case with a solid growth pattern > 30%, it is not surprising that we did not detect any of these mutations.

While solid-type AdCC is generally considered to have a poor prognosis, the extent of solid regions that predict a poor prognosis is not firmly established. The presence of solid growth pattern < 30% did not correlate with poor outcome in our study but our findings are in line with the current (and upcoming) World Health Organization (WHO) classification for salivary gland tumors, which suggests that AdCC with a solid component comprising more than 30% of the tumor may exhibit a poorer clinical outcome55.

High-grade transformation, which was originally described by Cheuk et al. in 1999 as “dedifferentiation”56, has been associated with aggressive clinical behavior in AdCC, even compared to the solid variant, with a high propensity for metastasis, as well as rapid growth57. Seethala et al. reported a median survival of approximately 36 months for this subtype26. In our study, two patients had a high-grade transformation, with one lost to follow-up after 1 year and found to have metastasis, while the other died after 35 months, consistent with the literature.

Histologically, high-grade transformation in AdCC is characterized by nuclear enlargement and irregularity, higher mitotic counts, and loss of biphasic ductal-myoepithelial differentiation27. We found that the presence of necrosis or a high mitotic index alone had no association with poor outcomes. This implies that the simultaneous occurrence of all components, indicative of high-grade transformation, is required for a significant association.

Perineural invasion is a characteristic feature of AdCC and was observed in 43% of cases in our study, consistent with the literature3,58. The significance of perineural invasion on OS in AdCC has been a matter of debate, with some studies indicating a poor prognosis59,60,61,62, while others have failed to establish a significant link63,64,65. Consistent with the latter findings, our study did not reveal an association. Some authors emphasize the importance of the extent of invasion, including intraneural invasion4 and the distinction between microscopic and macroscopic invasion of major nerves66,67. This may explain the divergent findings in the literature.

To the best of our knowledge, we present the first study to examine the prognostic value of metatypical features of AdCC since its description in 2022 by Mathew et al.29. To ensure homogeneity, an experienced pathologist at our institution reviewed all samples and excluded 12.5% of patients initially misdiagnosed with sinonasal AdCC, while they had HMSC, which has a much more favorable prognosis68. Zupancic et al. reviewed 68 AdCC cases, with eight in the sinonasal and nasopharyngeal region69. One case was reclassified as HMSC after pathological review, representing 12.5% of this subset, which aligns with our findings. Misdiagnosis rates in other studies without pathological review may lead to biased outcomes. This study has another notable strength in terms of follow-up duration, with a median follow-up time of 10.3 years and a span of up to 46.5 years. This extended follow-up is particularly significant given the tendency of this tumor to recur late, making it essential for analyzing long-term outcomes. To ensure this long-term follow-up, patients with an initial diagnosis before 2000 were also included. However, only patients from whom we had available tissue samples, allowing for the confirmation of diagnosis with certainty, were included in the analysis. Our study has further limitations due to its retrospective design and the inclusion of tumors from various anatomical structures (sinonasal tract, nasopharynx, and skull base), and inclusion of cases where tumor staging showed lymph node involvement and distant metastases. Although it would have been optimal to exclude these cases or analyze them separately for participant homogeneity, doing so would have resulted in a smaller sample size. Furthermore, given the limited sample size, we opted to use the log-rank test to investigate the prognostic value of factors rather than more sophisticated statistical techniques, such as Cox-regression. Although the sample size in this study was small, it reflects the rare and challenging nature of sinonasal AdCC.

Our study emphasizes the importance of accurate pathological diagnosis and imaging localization for assessment of prognostic features in sinonasal AdCC. Solid variant (> 30% solid growth pattern), high-grade transformation, and involvement of the sphenoid sinus are negative prognostic factors for the outcome of sinonasal AdCC. A high prevalence of MYB::NFIB gene fusions may help in the correct classification of diagnostically challenging (e.g. metatypical) cases.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Castelnuovo, P. & Turri-Zanoni, M. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. Adv. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 84, 197–209 (2020).

de Morais, E. F. et al. Prognostic factors and survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: A retrospective clinical and histopathological analysis of patients seen at a cancer center. Head Neck Pathol. 15, 416–424 (2021).

Ju, J. et al. The role of perineural invasion on head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 122(6), 691–701 (2016).

Amit, M. et al. International collaborative validation of intraneural invasion as a prognostic marker in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 37(7), 1038–1045 (2015).

Kim, S. A., Chung, Y. S. & Lee, B. J. Recurrence patterns of sinonasal cancers after a 5-year disease-free period. Laryngoscope 129(11), 2451–2457 (2019).

Ellington, C. L. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Incidence and survival trends based on 1973–2007 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. Cancer 118(18), 4444–4451 (2012).

Atallah, S. et al. A prospective multicentre REFCOR study of 470 cases of head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: Epidemiology and prognostic factors. Eur. J. Cancer 130, 241–249 (2020).

Amit, M. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 74(3), 118–125 (2013).

Bjørndal, K. et al. Salivary gland carcinoma in Denmark 1990–2005: A national study of incidence, site and histology. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Oral Oncol. 47(7), 677–82 (2011).

Amit, M. et al. Analysis of failure in patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. An international collaborative study. Head Neck 36(7), 998–1004 (2014).

Unsal, A. A., Chung, S. Y., Zhou, A. H., Baredes, S. & Eloy, J. A. Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: A population-based analysis of 694 cases. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 7(3), 312–320 (2017).

Mays, A. C. et al. Prognostic factors and survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal cavity. Head Neck 40(12), 2596–2605 (2018).

Meerwein, C. M., Pazahr, S., Soyka, M. B., Hüllner, M. W. & Holzmann, D. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging compared to surgical exploration for anterior skull base and medial orbital wall infiltration in advanced sinonasal tumors. Head Neck 42(8), 2002–2012 (2020).

Husain, Q. et al. Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: Systematic review of survival and treatment strategies. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 148(1), 29–39 (2013).

Coca-Pelaz, A. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—An update. Oral Oncol. 51(7), 652–661 (2015).

Trope, M. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal tract: A review of the national cancer database. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 9(4), 427–434 (2019).

Porcheri, C., Meisel, C. T. & Mitsiadis, T. A. Molecular and cellular modelling of salivary gland tumors open new landscapes in diagnosis and treatment. Cancers 12(11), 3107 (2020).

Thompson, L. D. R., Lewis, J. S., Skálová, A. & Bishop, J. A. Don’t stop the champions of research now: A brief history of head and neck pathology developments. Hum. Pathol. 95, 1–23 (2020).

Moskaluk, C. A. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: Clinical and molecular features. Head Neck Pathol. 7(1), 17–22 (2013).

Du, F., Zhou, C.-X. & Gao, Y. Myoepithelial differentiation in cribriform, tubular and solid pattern of adenoid cystic carcinoma: A potential involvement in histological grading and prognosis. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 22, 12–17 (2016).

da Cruz Perez, D. E., de Abreu, A. F., Nobuko Nishimoto, I., de Almeida, O. P. & Kowalski, L. P. Prognostic factors in head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 42(2), 139–146 (2006).

Spiro, R. H., Huvos, A. G. & Strong, E. W. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary origin: A clinicopathologic study of 242 cases. Am. J. Surg. 128(4), 512–520 (1974).

Perzin, K. H., Gullane, P. & Clairmont, A. C. Adenoid cystic carcinomas arising in salivary glands: A correlation of histologic features and clinical course. Cancer 42(1), 265–282 (1978).

Szanto, P. A., Luna, M. A., Tortoledo, M. E. & White, R. A. Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Cancer 54(6), 1062–1069 (1984).

van Weert, S., van der Waal, I., Witte, B. I., Leemans, C. R. & Bloemena, E. Histopathological grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Analysis of currently used grading systems and proposal for a simplified grading scheme. Oral Oncol. 51(1), 71–76 (2015).

Seethala, R. R., Hunt, J. L., Baloch, Z. W., Livolsi, V. A. & Leon, B. E. Adenoid cystic carcinoma with high-grade transformation: A report of 11 cases and a review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 31(11), 1683–1694 (2007).

Hellquist, H. et al. Cervical lymph node metastasis in high-grade transformation of head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: A collective international review. Adv. Ther. 33(3), 357–368 (2016).

Ooms, K. D. W., Chiosea, S., Lamarre, E. & Shah, A. A. Sebaceous differentiation as another feature of metatypical adenoid cystic carcinoma: A case report and letter to the editor. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 47(1), 145–146 (2023).

Mathew, E. P. et al. Metatypical adenoid cystic carcinoma: A variant showing prominent squamous differentiation with a predilection for the sinonasal tract and skull base. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 06, 06 (2021).

Bishop, J. A. Proceedings of the North American Society of Head and Neck Pathology, Los Angeles, CA, March 20, 2022: Emerging entities in salivary gland tumor pathology. Head Neck Pathol. 16(1), 179–189 (2022).

Ward, M. L., Kernig, M. & Willson, T. J. HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Laryngoscope 131(1), 106–110 (2021).

Chen, C. C. & Yang, S. F. Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features of the sinonasal tract (also known as human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma). Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 143(11), 1420–1424 (2019).

Virk, J. S. et al. Sinonasal cancer: An overview of the emerging subtypes. J. Laryngol. Otol. 134(3), 191–196 (2020).

Bishop, J. A. Newly described tumor entities in sinonasal tract pathology. Head Neck Pathol. 10(1), 23–31 (2016).

Freiberger, S. N. et al. SalvGlandDx—A comprehensive salivary gland neoplasm specific next generation sequencing panel to facilitate diagnosis and identify therapeutic targets. Neoplasia 23(5), 473–487 (2021).

Rupp, N. J. et al. HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: Four cases that expand the morpho-molecular spectrum and include occupational data. Head Neck Pathol. 14(3), 623–629 (2020).

Brierley, J. D., Gospodarowicz, M. K. & Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (Wiley, 2017).

Elliot, A. et al. Sinonasal malignancies in Sweden 1960–2010: A nationwide study of the Swedish population. Rhinology 53(1), 75–80 (2015).

Lupinetti, A. D. et al. Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 110(12), 2726–2731 (2007).

Miller, E. D. et al. Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: Treatment outcomes and association with human papillomavirus. Head Neck 39(7), 1405–1411 (2017).

Lee, Y. C. et al. Cavernous sinus involvement is not a risk factor for the primary tumor site treatment outcome of Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 47(1), 12 (2018).

Seong, S. Y. et al. Treatment outcomes of sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: 30 cases from a single institution. J. Cranio-Maxillo-Fac. Surg. 42(5), e171–e175 (2014).

Michel, G. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses: Retrospective series and review of the literature. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 130(5), 257–262 (2013).

Dagan, R. et al. Long-term outcomes from proton therapy for sinonasal cancers. Int. J. Part. Ther. 8(1), 200–212 (2021).

Pantvaidya, G. H., Vaidya, A. D., Metgudmath, R., Kane, S. V. & D’Cruz, A. K. Minor salivary gland tumors of the sinonasal region: Results of a retrospective analysis with review of literature. Head Neck 34(12), 1704–1710 (2012).

Lisan, Q. et al. Management of orbital invasion in sinonasal malignancies. Head Neck 38(11), 1650–1656 (2016).

Persson, M. et al. Rearrangements, expression, and clinical significance of MYB and MYBL1 in adenoid cystic carcinoma: A multi-institutional study. Cancers 14(15), 3691 (2022).

Rooper, L. M., Lombardo, K. A., Oliai, B. R., Ha, P. K. & Bishop, J. A. MYB RNA in situ hybridization facilitates sensitive and specific diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma regardless of translocation status. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 45(4), 488–497 (2021).

Wagner, V. P., Bingle, C. D. & Bingle, L. MYB-NFIB fusion transcript in adenoid cystic carcinoma: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 176, 103745 (2022).

Liu, X., Chen, D., Lao, X. & Liang, Y. The value of MYB as a prognostic marker for adenoid cystic carcinoma: Meta-analysis. Head Neck 41(5), 1517–1524 (2019).

de Almeida-Pinto, Y. D. et al. t(6;9)(MYB-NFIB) in head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 25(5), 1277–1282 (2019).

Weinreb, I. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma with striking tubular hypereosinophilia: A unique pattern associated with nonparotid location and both canonical and novel: EWSR1::MYB: and: FUS::MYB: fusions. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 47(4), 497–503 (2023).

Ferrarotto, R. et al. Activating NOTCH1 mutations define a distinct subgroup of patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma who have poor prognosis, propensity to bone and liver metastasis, and potential responsiveness to Notch1 inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 35(3), 352–360 (2017).

Ho, A. S. et al. Genetic hallmarks of recurrent/metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma. J. Clin. Investig. 129(10), 4276–4289 (2019).

Thompson, L. D. R. & Franchi, A. New tumor entities in the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Virchows Archiv. 472(3), 315–330 (2018).

Cheuk, W., Chan, J. K. & Ngan, R. K. Dedifferentiation in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland: An uncommon complication associated with an accelerated clinical course. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 23(4), 465–472 (1999).

Chia, N. & Petersson, F. Adenoid cystic carcinoma with dedifferentiation/expansion of the luminal cell component and preserved biphasic morphology—Early high-grade transformation. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 50, 151650 (2021).

Dantas, A. N., Morais, E. F., Macedo, R. A., Tinôco, J. M. & Morais, M. D. Clinicopathological characteristics and perineural invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma: A systematic review. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 81(3), 329–335 (2015).

Volpi, L. et al. Endoscopic endonasal resection of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal tract and skull base. Laryngoscope 129(5), 1071–1077 (2019).

Wang, Z. K. et al. Treatment and prognosis analysis of perineural invasion on sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 44(2), 185–191 (2022).

Thompson, L. D. et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 8(1), 88–109 (2014).

Lukšić, I., Suton, P., Macan, D. & Dinjar, K. Intraoral adenoid cystic carcinoma: Is the presence of perineural invasion associated with the size of the primary tumour, local extension, surgical margins, distant metastases, and outcome? I just. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 52(3), 214–218 (2014).

Bianchi, B. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of intraoral minor salivary glands. Oral Oncol. 44(11), 1026–1031 (2008).

Sur, R. K. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands: A review of 10 years. The Laryngoscope 107(9), 1276–1280 (1997).

Shen, C., Xu, T., Huang, C., Hu, C. & He, S. Treatment outcomes and prognostic features in adenoid cystic carcinoma originated from the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 48(5), 445–449 (2012).

Fordice, J., Kershaw, C., El-Naggar, A. & Goepfert, H. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 125(2), 149–152 (1999).

Garden, A. S., Weber, R. S., Morrison, W. H., Ang, K. K. & Peters, L. J. The influence of positive margins and nerve invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck treated with surgery and radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 32(3), 619–626 (1995).

Bishop, J. A. et al. HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: An expanded series of 49 cases of the tumor formerly known as HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic carcinoma-like features. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 41(12), 1690–1701 (2017).

Zupancic, M. & Näsman, A. Human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma—An even broader tumor entity? Viruses 13(9), 1861 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Institute of Pathology, Cantonal Hospital Basel-Landschaft, Liestal, Switzerland (Prof. Kirsten Mertz), and Viollier Basel, Switzerland for submitting pertinent material for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TM was responsible for data extraction, statistical analysis, and writing the study. She had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CMM provided guidance and support throughout the project and assisted with data extraction and preparation of the manuscript. DH contributed to the study design and provided input on the research concept. MBS and SAM offered valuable input during discussions and reviewed the study. UH provided consultation for the statistical analysis, including advice on appropriate methods and interpretation of the results. SNF and NJR completed the pathological work-up, including genetic sequencing, and provided consulting function for all questions related to pathology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mauthe, T., Meerwein, C.M., Holzmann, D. et al. Outcome-oriented clinicopathological reappraisal of sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma with broad morphological spectrum and high MYB::NFIB prevalence. Sci Rep 14, 18655 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69039-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69039-6

This article is cited by

-

Besonderheiten in der Erforschung und Diagnostik seltener Erkrankungen

Die Pathologie (2025)