Abstract

Due to the multiple influences of unique physicochemical properties of helium, petrographic characteristics and temperature and pressure conditions, little is known about the helium adsorption behaviors in minerals and rocks at geological conditions. Based on the grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations, this study revealed the adsorption characteristics of pure helium and the competitive adsorption of binary mixtures with different proportions of methane and helium under geological temperature and pressure conditions in quartz slit model. Molecular simulation of pure helium shows that physical adsorption of helium exists in mineral surfaces, which indicates a preservation mechanism of helium in helium source rocks. Binary mixtures simulations indicate that the adsorption capacity of methane in quartz is stronger than that of helium, and the competitive adsorption of methane increases with decreasing burial depth. This means that during the upwards migration processes of natural gas, the adsorbed helium that distributed in the migration pathway will be gradually displaced by methane, then concentrate in the hydrocarbon gases and subsequently accumulate together in favorable traps to form helium-rich natural gas reservoirs. Our results provide a molecular-scale insight into the preservation and accumulation of helium in helium source rocks and are significant for assessing the helium resource potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helium (He) as an exhaustible and irreplaceable noble gas, has been widely used in many significant fields such as aviation, medical, cryogenic superconductor, military and nuclear industry, but it has been in short supply1,2. Actually, helium as an associated resource has been discovered serendipitously in the process of oil and gas exploration3,4. Helium-4 (4He) is the main industrial helium, which is a decay product primarily from uranium and thorium (U and Th) in various rocks5,6. Therefore, considering the abundance and the half-life of radioactive elements, the ancient granite rich in U and Th elements is an important helium source rock type7. Previous studies have further shown that the helium in many gas fields around the world, such as the Hugoton-Panhandle gas field in the USA8,9, the Hassi R'Mel gas fields in Algeria10, the Weiyuan gas field in China11,12 and the Dongping gas field in China13, originate at least in part from granitic basement. In addition to the strong ability to generate helium of granitic basement, the widely developed microfractures in granitic basement play a vital role in the helium accumulation process, providing favorable conditions for the release, migration and preservation of helium13,14. Whole-rock heating experiments have shown that more than 60% of the helium content generated by granite can be retained in the exposed granite under low temperature and pressure environments, depending on the low diffusion coefficient of helium in the granite under the surface condition15. However, several studies proposed that helium can also be effectively preserved in the deep buried, high-temperature and high-pressure helium source rocks7,16,17,18,19. In detail, Ballentine et al. (1991) calculated that the helium content in the gas fields in the Pannonian Basin is higher than the amount of radiogenic helium generated by the entire crust beneath the basin since the basin formation. This therefore reveals that before the basin formation, a large amount of helium had been generated and stored in the basement helium source rock, some of which had been preserved until the hydrocarbon accumulation stage and then transported to the shallow reservoirs16. Lowenstern et al. (2014) also proposed that a certain amount of crustal-derived helium can be accumulated and stored in deep basement for many hundreds of million years based on the fact that the helium emission rate in Yellowstone exceed any conceivable rate of generation in the crust17. In the granitic bedrock reservoirs with a burial depth of 3182 m in Dongping gas field, China, it has been detected that the preserved helium concentration can reach up to 0.48%18, and the stepwise heating experiments also confirmed that some helium can be effectively preserved in the deep buried granite7.

In the sedimentary sequences, helium typically dissolves and accumulates in groundwater20,21, whereas in the basement rocks, the deep burial granitic basement usually has low porosity and moisture content, helium can be preserved not only in dissolved state in the pore water, but also in other occurrence states for preservation, such as the adsorbed state. Due to the existence of van der Waals forces exists among all kinds of atoms and molecules, physical adsorption (van der Waals adsorption) that caused by the van der Waals force between the adsorbate and the adsorbent can occur on any solid surface22. However, the adsorption behaviors of helium in the mineral surface have not been clearly researched, which restrict the process of helium resource exploration.

Molecular simulation can directly display intermolecular interaction and chemical reaction processes on molecular or even atomic level by computer modelling technology23, which has been widely used in unconventional petroleum exploration24,25,26. Therefore, this study mainly relies on molecular simulation technology to reveal the adsorption behaviors of pure helium and binary mixtures of methane and helium in the quartz slit model under geological temperature and pressure conditions. In order to better understand the helium preservation and accumulation mechanism at geological conditions, this study simulated competitive adsorption experiments of six groups of helium-containing hydrocarbon gas at high-pressure and high-temperature conditions.

Computational details

Molecular model

Granite can act as both helium source rock and reservoir simultaneously in the helium accumulation process13,14, quartz as the most common essential mineral in granite generally accounts for 20–40% of the granite mass and some samples can reach 60%13, the adsorption of helium in quartz is important and quartz was chosen to be the adsorbent in this study.

As the most stable structure of α-quartz27, the (001) face in the unit cell was chosen to construct a 7 × 7 × 3 supercell structure with periodicity in a, b and c directions. As shown in Fig. 1, the parameters of the 7 × 7 × 3 supercell structure along a, b and c directions are 3.44 nm, 3.44 nm and 1.62 nm, respectively. Similar models of quartz slit have been adopted to study the correction of shale gas adsorption capacity by performing the grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) method28. Meanwhile, the α-quartz slit is regarded as a rigid model.

The top view (a) and side view (b) of the α-quartz slit with width of 2.00 nm. The figure was generated in the BIOVIA Materials Studio 2017 (URL Link: https://www.3ds.com/products/biovia/materials-studio).

GCMC simulation

To simulate the adsorption mechanisms of helium-rich natural gases, the GCMC simulations were performed by using Sorption code29. The Condensed-phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies (COMPASS) force field30 was taken into account in the whole simulation processes. In our simulations, non-bond energies were determined by using both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. The Ewald summation method was applied to calculate the long-range Coulomb interaction with an accuracy of 10–5 kcal/mol. The Atom-based summation method was adopted to determine the short-range Van der Waals interaction with a cutoff length of 18.5 Ǻ and a bond width of 1.0 Ǻ. Both adsorption isotherm and fixed-pressure simulations comprised a total of 7 × 107 Monte Carlo steps, of which 5 × 107 were system equilibrium steps and 2 × 107 were statistical average steps. The adsorption capacity (Γ, m3/t) was defined as follows:

where N is the number of adsorbed molecules, M is the relative molecular mass of the adsorbent, and Vm is the molar volume (Vm = 22.414 L/mol under standard conditions).

The adsorption isotherms were evaluated by the Langmuir model25,

where \(\Gamma_{Max}\) (m3/t) is the largest gas adsorption capacity, p (MPa) is pressure and \(\kappa\) (MPa−1) is the Langmuir coefficient.

To evaluate the competitive adsorption and adsorption priority of mixed gas, adsorption selectivity (\(S_{{CH_{4} /He}}\)) is defined as:

where \(x_{{CH_{4} }}\) and \(x_{He}\) are the mole fractions of CH4 and He in the adsorbed phase, respectively; \(y_{{CH_{4} }}\) and \(y_{He}\) are the mole fractions of CH4 and He in the bulk phase, respectively.

Geological settings

Gas components

The adsorption behaviors of pure helium in quartz slit were conducted to acquire the adsorption capacity of pure helium in quartz. Statistical analysis shows that the helium concentration in the natural gas reservoirs is typically lower than 10% (mole fraction)31 and is higher than 0.1% in helium-rich natural gas reservoir8. Because the hydrocarbon gas reservoir is the most important type of helium-rich natural gas reservoir31,32, we selected the CH4-He binary mixtures for competitive adsorption simulation in quartz slit model. According to the Dalton’s law of partial pressures, the total pressure of mixed gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of each constituent gas. The mole fraction of a constituent gas is equal to its partial pressure divided by the total pressure of mixed gas. Therefore, the mole fraction of helium in the GCMC simulation is realized by setting the partial pressure of helium and the total pressure of mixed gas. In this study, the helium mole fractions of 50%, 10%, 5.0%, 1.0%, 0.5% and 0.1% were set in the CH4-He binary mixtures, which roughly represents the variation of helium concentration in helium generation, migration and accumulation processes.

Simulated temperature and pressure settings

In this study, the simulation experiments were set at high-temperature and high-pressure conditions which are closer to the geological background. Four simulated temperatures at 318, 368, 418, and 493 K were set in the isotherm adsorption experiments and the simulated pressure ranging from 0 to 200 MPa for each simulated temperature condition. Moreover, the commonly-assumed normal gradient of 25 °C/km for continents is valid for the range (1.5–12.5 km) of sedimentary cover-thickness33, so the geothermal gradient in the study is set at 25 °C/km with the surface temperature of 20 °C, the four selected simulated temperatures correspond to the temperatures at depths of 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, and 8.0 km.

Result

Pure gas adsorption

Pure helium adsorptions in quartz slit were simulated at temperatures of 318, 368, 418 and 493 K by GCMC simulations. Adsorption isotherms of pure helium under pressure of 0 to 200 MPa were plotted in Fig. 2. The isotherms are fitted by the Langmuir model, and the Langmuir model has good fitting accuracy for helium adsorption isotherms (R2 > 0.99, R2 is the coefficient of determination, Table S1). The adsorption capacity of helium increases with the increase of pressure, and decrease with the increase of temperature. Besides, the helium adsorption isotherms do not reach adsorption equilibrium even at 200 MPa.

Mixed gases adsorption

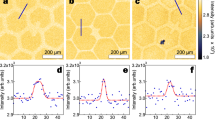

The adsorption behaviors of six groups of CH4-He binary mixtures with helium mole fraction of 50%, 10%, 5%, 1%, 0.5% and 0.1% in quartz slit were simulated in this study. The adsorption isotherms for the mixed gases, He and CH4 at 318, 368, 418 and 493 K are illustrated in Figs. 3, 4 and 5, respectively. The Langmuir model also have good fitting accuracy for mixed gases, He and CH4 adsorption isotherms (R2 > 0.99, Table S2-13). The tendency of mixed gases adsorption isotherms is that the adsorption capacity increases gradually during the whole processes of pressure increase from 0 to 200 MPa. In Fig. 3, it can be observed that for the mole fractions of helium less than 10%, the adsorption isotherms of mixed gases with different proportions exhibit a nearly overlapping pattern. Additionally, the variation characteristics of adsorption isotherm of each mixed gas displays a remarkable similarity to the CH4 adsorption isotherm at the same temperature (Fig. 5), but are completely different from those of helium (Fig. 4). The adsorption capacity of mixed gases increases significantly when the helium mole fraction reaches 50% under high-pressure conditions (> 100 MPa). In contrast, under low-pressure conditions (< 100 MPa), the opposite trend is observed, where the adsorption capacity is higher for mixed gases with lower helium mole fractions (0.1–10%) compared to those with a helium mole fraction of 50%. The simulation results provide important insights into the adsorption behavior of helium-rich natural gases and highlight the unique behavior of helium as compared to other gases.

As the helium mole fraction increases from 0.1 to 50% in the mixed gases, the adsorption capacity of helium significantly increases (Fig. 4), whereas the adsorption capacity of CH4 gradually decreases (Fig. 5). Generally, the adsorption capacity of natural gas gradually decreases with the simulated temperature increases, which also observed in our study as expected from the CH4 adsorption capacity (Fig. 5). For example, the equilibrium or maximum CH4 adsorption capacity with the helium mole fraction of 50% decreases from 88 m3/t at 318 K to 54 m3/t at 493 K (Fig. 5, Table S10 and 13). However, an interesting observation is that regardless of helium mole fraction, the adsorption capacity of helium does not show a significant decrease with increasing temperature, but rather slightly increases (Fig. 4). This may be resulted from the release of adsorption sites through thermal desorption of CH4 and these adsorption sites then are occupied by helium, which result in a slight increase of the adsorption capacity of helium in quartz. In addition, under the same temperature and pressure conditions, the adsorption capacity of CH4 is always higher than He in the binary mixtures in quartz slit, which indicates that the order of competitive adsorption is CH4 > He.

Selective adsorption of CH4 and He

The adsorption process of mixed gases is a competitive adsorption behavior that focuses on comparison between binary mixtures, which is easily understood by using a definition of adsorption selectivity. The CH4/He adsorption selectivity for CH4-He binary mixtures with different helium mole fraction of 0.1%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 5.0%, 10%, 50% at temperatures of 318, 368, 418 and 493 K in quartz slit is illustrated in Fig. 6. Under the given simulation conditions, the CH4/He adsorption selectivity value is always higher than 1.0, which means that the adsorption capacity of CH4 in quartz is stronger than that of helium. The CH4/He adsorption selectivity values of binary mixtures with different helium mole fractions have similar variation characteristics, that is, as pressure increases, the value rapidly increase to a maximum value and then gradually decreases. The maximum CH4/He adsorption selectivity values for the mixed gases containing the same helium mole fraction gradually decrease with the increase of temperature. Under the same temperature and pressure conditions, the CH4/He adsorption selectivity values vary within a relative narrow range when the helium mole fraction is in the range of 0.1%‒10%. However, the CH4/He adsorption selectivity value markedly decreases under relative low pressure as the helium mole fraction increases from 10 to 50%, while the CH4/He adsorption selectivity value only fluctuates slightly under relative high-pressure conditions.

Discussion

Helium preservation mechanism in helium source rock

Generally, granitic basement is an effective helium source rock with plentiful of U and Th, tremendous volume and prolonged geological age8,31,34. The main helium generating minerals in granitic basement are accessory minerals rich in U and Th, which include uraninite, thorite, monazite, apatite and zircon6,7,15,35, and are often distributed within essential magmatic minerals, such as quartz, plagioclase and biotite (Fig. 7)5,7. Moreover, a large number of nanopores and microfractures were observed in granite (Fig. 7) 14,36,37, which provides good conditions for the adsorption and preservation of helium. Usually, granitic basement with deep burial depth has low porosity and moisture content, thus, except for dissolve in the pore water as dissolved state, helium probably has other occurrence state. In this study, the adsorption isotherms reveal that physical adsorption of helium occurred in quartz slit (Fig. 2b). Because the physical adsorption that caused by the van der Waals force between the adsorbate and the adsorbent can occur on any solid surface22, the adsorption of helium probably exists on any mineral surfaces, such as quartz, feldspar and mica. Therefore, after releasing from the helium generating minerals in granitic basement, helium can be adsorbed in different mineral surfaces and the widespread nanopores as adsorbed phase. Helium adsorbed in these spaces can also be well preserved in granitic basement and released in late episodic tectonic events38,39,40. Generally, the helium mole fraction in discovered helium-rich gas reservoirs is less than 10% 31,41, but we cannot deny that the helium mole fraction in the nanoscale space of the helium source rock may be extremely high. The simulation results show that even if the helium mole fraction is only 50% or lower, the helium adsorption amount in its source rock is still valuable (Fig. 8). The helium adsorption behaviors reveal a potential helium preservation mechanism in helium source rock, that is, when helium is released from its generating minerals, it will be effectively adsorbed in nanoscale spaces in the helium source rocks.

Figure 8 shows that the adsorption capacity of pure helium increases with increasing burial depth (equivalent to the simultaneous increase of temperature and pressure), but decreases with increasing temperature (Fig. 2), which indicates that the decreased adsorption amount of helium caused by the increasing of temperature is much smaller than the increased adsorption amount of helium caused by the increasing of pressure. Hence, the geological pressure is the primary factor determining the adsorption amount of helium in helium source rocks, because high pressure would strengthen the interactions between the adsorbent and gas molecules. Moreover, as the coefficient of formation pressure (CP) increases from 1.0 to 2.0 (corresponding pressure gradient is 10 MPa/km and 20 MPa/km), also refers to the doubling of formation pressure, the adsorption amount of helium increases significantly. For example, at the burial depth of 3.0 km, the adsorption amount of pure helium in over pressured formation with CP = 2.0 (corresponding pressure of 60 MPa) is about 70.0 m3/t, which is markedly higher than that in normal pressured formation (CP = 1.0 and corresponding pressure of 30 MPa) with the adsorption amount of pure helium of about 40.0 m3/t. This indicates that the overpressure helium source rock can adsorb and preserve more helium than the normal-pressure helium source rock (Fig. 8). Previous study has proved that when the burial temperature of the granitic basement exceeds 250 °C, helium will be completely released from its generating minerals, then resulting in the dissipation of helium that generated in the early stage7. For the deeply buried granitic basement, although the high temperature will promote the helium release from its generating minerals7, the high pressure can facilitate the helium adsorption in microfractures (Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 8, the deep burial condition with high temperature and pressure is conducive to the helium adsorption, which further confirms that helium will not completely dissipate after being released from its generating minerals, but will be adsorbed in the granitic basement.

Previous studies have also recognized that the ancient granitic basements can generate and preserve large amounts of helium16,17,18, but the helium preservation mechanism has not yet been clearly defined. For example, the emission rate of crustal-derived helium at Yellowstone exceeds any conceivable helium generation rate in the crust, which indicate that 4He has been preserved for billions of years in the Archean cratonic rocks beneath Yellowstone18. In addition to being partially dissolved and stored in formation water17, helium can also be partially adsorbed in the microfractures and unconnected pores in the basement of Yellowstone, which was then preserved in situ for a long time due to the stable tectonic condition. Moreover, the adsorption capacity of helium may be large enough on a geologic time-scale to achieve such a large helium emission amount at Yellowstone. Over the past two million years, mass of the adsorbed helium probably desorbed and dissolved in the mantle fluids with a temperature up to 340 °C caused by the intense crustal metamorphism at Yellowstone17. This indicates that late tectonic activities can effectively promote the desorption and release of helium that preserved in the basement. For example, the helium in the Rukwa Basin in Tanzania42, Weiyuan gas field43, Hetianhe gas field44 and Dongping gas field45 in China were released from the basement and accumulated in favorable reservoirs due to the late intense tectonic activities, such as active faults and basement uplift32.

From Fig. 8, it can be seen that the adsorption amount of helium decreases with the decrease of the burial depth, indicating that the uplift of granitic basement will lead to the desorption of helium. Therefore, the late uplift of the basement is beneficial for the formation of helium-rich natural gas reservoirs, as the later the uplift, the smaller the helium loss of the gas reservoirs caused by diffusion. For example, helium in the Precambrian and Cambrian reservoirs in the Weiyuan gas fields in China has an average concentration of 2785.7 ppm and was mainly generated from the granitic basement11. Helium may be well preserved in the granitic basement before the intense basement uplift, and amounts of helium released from the granitic basement and then accumulated in the reservoirs during the intense uplift stage in the Himalayan orogeny period11,32. The rapid uplift of strata (~ 2000 m) during the Neogene in the Weiyuan area41 resulted in a significant desorption of adsorbed helium in the granitic basemen, which is attributed to the decrease of temperature and pressure of the granitic basement (Fig. 8). Therefore, the desorbed helium would dissolve in pore fluid, which ultimately promoted the helium concentration in natural gas reservoirs in the Weiyuan gas fields. In conclusion, the stable tectonic environment is essential for helium preservation in the ancient granitic basements (i.e., helium source rock) and late tectonic activities is a key factor for helium accumulation in reservoirs.

Effect of competitive adsorption on helium enrichment

The pure helium reservoir is undiscovered, because of the slow generation rate and scatter distribution of helium in the crust41. Generally, helium in the reservoir is accumulated with other gases8,31,46, these gases act as carrier gas for the migration and accumulation of helium47 and will extract helium from the pore water and rock in the migration pathway34. At present, industrial helium is extracted from the natural gas reservoirs, and mainly from the helium-rich CH4 reservoirs (CH4 ≥ 50%, He ≥ 0.1%), such as the Hugoton-Panhandle gas field8, Hassi R’Mel gas field48 and Weiyuan gas field11. It is well known that methane is generated from organic matters in a specific thermal evolution period, which is completely different from helium, however, they coexist in the same gas reservoir. From the molecular scale, the competitive adsorption of helium and methane occurs when these gases coexist in the pore or fracture. The CH4/He adsorption selectivity is always higher than 1.0 in quartz slit at temperature of 318, 368, 418 and 493 K under the pressure range of 0.1‒200 MPa (Fig. 6), which means the adsorption capacity of methane in quartz is stronger than helium. Hence, the adsorbed helium in the migration pathways of hydrocarbon gas will be displaced by methane, and then concentrated in the hydrocarbon gas (carrier gas) as free phase. Interestingly, methane plays a bidirectional role in helium accumulation process. On the one hand, methane can tremendously dilute helium, which lead to the low concentration of helium in the natural gas reservoir. But on the other hand, it can also displace the adsorbed helium for helium enrichment, and this concentration mechanism is of great significance for the further helium accumulation in the reservoirs.

Previous statistical results of helium concentration and the depth of 8331 natural gas samples show that the peak of helium concentration occurs at 0.5 km, the helium concentrations decrease with the increasing depth, and the helium-rich gases (He > 0.1%) were mainly distributed in the reservoirs with depth below 3.0 km34. Liu et al. (2023) also analyzed the burial depth of 35 proven helium-rich natural gas reservoirs worldwide and noted that 33 were distributed in the formations with depth shallower than 3.0 km and none were found in formations below 5.0 km46. However, the reason for the high helium concentrations in shallow natural gas reservoirs has not been clearly defined. It is known that underground gas will persistently migrate upwards into the shallow crust before accumulate in favorable traps. In the upwards migration process, the CH4/He adsorption selectivity continuously increase as the gradual drop of the pressure and temperature (Fig. 9a), which indicates that methane has stronger displacement capacity on adsorbed helium in the relative shallow formations. Moreover, the percentage of helium adsorption amounts in total adsorption amounts of mixed gases also decrease as the decrease of burial depth (Fig. 9b), which indicates that more adsorbed helium will be displaced by methane in the shallower formations. By contrast, the helium concentration in free natural gas will gradually increase as methane continuously displaces adsorbed helium in the migration pathway and the helium concentration will become higher as the migration distance increase. Hence, on the basis of the competitive adsorption simulation results, relative high helium concentration will be discovered in relative shallow natural gas reservoirs.

Helium accumulation mechanism in granitic bedrock reservoir

Natural gas with main component of methane from the granitic bedrock reservoirs in the Dongping gas field of Qaidam Basin in China contains industrial helium, and the helium concentration is in the range of 0.02–0.81%19,45. Previous studies concluded that helium in the Dongping gas field is mainly crustal-derived helium and generated from the granitic bedrocks19,49 since from 410 Ma50 (Fig. 10). Before the Paleogene, the granitic bedrocks had undergone intensive weathering, leaching and erosion, which significantly improved the quality of the bedrock reservoir. Helium that generated in this process was partially lost due to the widespread cleavage fractures, tectonic fractures and dissolved pores that developed in the fracture zone on the top of the granitic bedrocks and partially adsorbed and trapped in the unweathered granitic bedrocks. Since the Paleogene, a set of top filling caprocks were formed by the filling of gypsum and calcite in the top of bedrocks, and provided good sealing conditions for the helium-rich natural gas reservoir13 (Fig. 11a). Previous study shows that quartz is a main mineral component in the bedrocks in the Dongping area and has a highest average content of 40%13. Based on the adsorption behaviors of helium in quartz slit, helium that generated after the formation of caprocks can be adsorbed and preserved in the pores and fractures in situ in the granitic basement (Fig. 11b). Hydrocarbon gas in the Dongping area was generated from the Jurassic coal-bearing source rock that entered into the major gas generation period in the Miocene, and was gradually charged into the granitic bedrock reservoirs from the late Miocene to present45 (Figs. 10 and 11c). In the process of hydrocarbon gas migrated along the faults and unconformity, the helium that adsorbed in the migration passways would be displaced by hydrocarbon gas (e. g. CH4) due to the stronger adsorption capacities of methane than helium (Figs. 9 and 11d). The competitive adsorption behaviors of CH4-He with different helium mole fractions of 50%, 10%, 5%, 1%, 0.5% and 0.1% display that the competitive adsorption capacity of methane increases as more methane charges into the granitic bedrock reservoirs (Fig. 9a), meanwhile the helium adsorption amount decrease distinctly with the rise of methane mole fraction in the mixed gas (Figs. 4 and 9b). Moreover, because of the basement uplift and tectonic activities that happened in the late Neogene and Quaternary51, partial adsorbed helium desorbed as the temperature and pressure of the granitic bedrocks dropped (Fig. 8). Therefore, the free helium that displaced by methane and desorbed would dissolve in the hydrocarbon gas and accumulate in situ in the granitic bedrock reservoirs, and the displacement and desorption of helium both raises the content of helium in the natural gas reservoirs in the Dongping gas field.

Helium concentrations of the natural gases from the granitic bedrock reservoirs in wells Dongping 1 (Dp 1) and Dongping 3 (Dp 3) are 0.24% and 0.48%, respectively19,49, which may be caused by multiple factors, such as the differences of total amount of natural gas in the reservoirs and the helium generation capacity of the bedrocks. From the molecular scale, because the burial depth and pressure of granitic bedrock reservoir in well Dp 1 are larger than those in well Dp 3, the competitive adsorption capacity of methane in well Dp 3 is stronger than that in well Dp 1, which indicates that more helium was displaced by methane in situ in the granitic bedrock reservoir of well Dp 3 than that of well Dp 1. Furthermore, in the process of hydrocarbon gases migrated from well Dp 1 to Dp 3 along the unconformity (Fig. 11c), the adsorbed helium in the migration pathway would be displaced and concentrated into the hydrocarbon gases and subsequently charged into the granitic bedrock reservoir in well Dp 3. Moreover, the distance of basement uplift in well Dp3 is larger than in well Dp 1 after the late Neogene51 (Fig. 11c), resulting in a higher desorption amount of helium in the granitic bedrock of well Dp3 than that of well Dp 1. In summary, the different degree of competitive adsorption capacity of methane and the various desorption amount of helium are effective factors to induce the distinct helium concentrations between the granitic bedrock reservoirs of well Dp 3 and well Dp 1.

Conclusions

Physical adsorption of helium exists in quartz slit based on the molecular simulation of pure helium. Because the physical adsorption that caused by the van der Waals force can occur on any solid surface, the adsorption of helium probably exists on any mineral surfaces, such as quartz, feldspar and mica. The adsorption simulation of pure helium indicates that the adsorption of helium is a probable mechanism of helium preservation in helium source rock, and deep burial depth can promote the adsorption of helium.

Competitive adsorption simulation results of CH4-He binary mixtures in quartz slit indicate that the adsorbed helium will be displaced by methane, this process is vital for the helium concentration in free hydrocarbon gases. The competitive adsorption capacity of methane gets stronger as the decrease of burial depth, which would lead to the high helium concentration present in relative shallow natural gas reservoirs.

Before the late Miocene, helium can be adsorbed and preserved in the granitic basement in the Dongping gas field in China. After the late Miocene, the desorption of helium in the basement uplift stage and displacement by methane in the hydrocarbon gas charging period may improve the helium concentration in granitic bedrock reservoirs. In addition, the different helium concentration between the granitic bedrock reservoirs of well Dp1 and Dp3 may arise from the different competitive adsorption capacity of methane and different desorption amount of helium.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article and supplementary information file.

References

Nuttall, W. J. et al. Resources: Stop squandering helium. Nature 485, 573–575 (2012).

Anderson, S. T. Economics, helium, and the U.S. Federal helium reserve: Summary and outlook. Nat. Resour. Res. 27, 455–477 (2018).

Gluyas, J. G. The emergence of the helium industry. The history of helium exploration, Part 1. In AAPG Explorer 16–17 (2019a).

Gluyas, J. G. Helium shortages and emerging helium provinces. The history of helium exploration, Part 2. In AAPG Explorer 18–19 (2019b).

Bottomley, D. J. et al. Helium and neon isotope geochemistry of some ground waters from the Canadian Precambrian Shield. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 4, 1973–1985 (1984).

Ballentine, C. J. & Burnard, P. G. Production, release and transport of noble gases in the continental crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 481–538 (2002).

Zhang, W. et al. Granite is an effective helium source rock: Insights from the helium generation and release characteristics in granites from the North Qinling Orogen, China. Acta Geol. Sin Engl. 94, 114–125 (2020).

Ballentine, C. J. & Lollar Sherwood, B. Regional groundwater focusing of nitrogen and noble gases into the Hugoton-Panhandle giant gas field, USA. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 2483–2497 (2002).

Sorenson, R. P. A dynamic model for the Permian Panhandle and Hugoton fields, western Anadarko basin. AAPG Bull. 89, 921–938 (2005).

Sabaou, N. Chemostratigraphy, tectonic setting and provenance of the Cambro–Ordovician clastic deposits of the subsurface Algerian Sahara. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 55, 158–174 (2009).

Wang, X. et al. Radiogenic helium concentration and isotope variations in crustal gas pools from Sichuan Basin, China. Appl. Geochem. 117, 104586 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Feasibility of high-helium natural gas exploration in the Presinian strata, the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2, 88–94 (2015).

Ma, F. et al. Bedrock gas reservoirs in Dongping area of Qaidam Basin, NW China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 42, 293–300 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Dual contribution of granites in helium accumulation: source and reservoir. Northwest. Geol. 55, 95–102 (2022) ((in Chinese)).

Martel, D. J. et al. The role of element distribution in production and release of radiogenic helium: the Carnmenellis Granite, southwest England. Chem. Geol. 88, 207–221 (1990).

Ballentine, C. J. et al. Rare gas constraints on hydrocarbon accumulation, crustal degassing and groundwater flow in the Pannonian Basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 105, 229–246 (1991).

Chiodini, G. et al. Insights from fumarole gas geochemistry on the origin of hydrothermal fluids on the Yellowstone Plateau. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 89, 265–278 (2012).

Lowenstern, J. B. et al. Prodigious degassing of a billion years of accumulated radiogenic helium at Yellowstone. Nature 506, 355–358 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. Quantifying the helium and hydrocarbon accumulation processes using noble gases in the North Qaidam Basin. China. Chem. Geol. 525, 368–379 (2019).

Torgersen, T. & Clarke, W. Helium accumulation in groundwater, I: An evaluation of sources and the continental flux of crustal 4He in the Great Artesian Basin, Australia. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 49, 1211–1218 (1985).

Aggarwal, P. K. et al. Continental degassing of 4He by surficial discharge of deep groundwater. Nat. Geosci. 8, 35–39 (2015).

Pourhakkak, P. et al. Fundamentals of adsorption technology. In Chapter 1 in Adsorption: Fundamental Processes and Applications, Vol. 33 1–70 (Interface Science and Technology, 2021)

Li, M. et al. Progress of molecular simulation application research in petroleum geochemistry. Oil Gas Geol. 42, 919–930 (2021) ((in Chinese)).

Huang, L. et al. Molecular simulation of adsorption behaviors of methane, carbon dioxide and their mixtures on kerogen: Effect of kerogen maturity and moisture content. Fuel 211, 159–172 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Molecular simulation of CH4, CO2, H2O and N2 molecules adsorption on heterogeneous surface models of coal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 389, 894–905 (2016).

Liu, N. et al. Mechanistic insight into the optimal recovery efficiency of CBM in subbituminous coal through molecular simulation. Fuel 266, 117137 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Finding stable α-quartz (0001) surface structures via simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 181911 (2008).

Yang, X. et al. Correction of gas adsorption capacity in quartz nanoslit and its application in recovering shale gas resources by CO2 injection: A molecular simulation. Energy 240, 122789 (2022).

Reinier, L. C. A., Neil, A. S. & Struan, H. R. Monte Carlo methods in materials studio. Mol. Simul. 39, 1153–1164 (2013).

Sun, H. et al. The COMPASS force field: parameterization and validation for phosphazenes. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 8, 229–246 (1998).

Broadhead, R. F. Helium in New Mexico-geologic distribution, resource demand and exploration possibilities. New Mexico Geol. 27, 93–101 (2005).

You, B. et al. Accumulation models and key conditions of crustal-derived helium-rich gas reservoirs. Nat. Gas Geosci. 34, 672–683 (2023) (in Chinese).

Kolawole, F. & Evenick, J. C. Global distribution of geothermal gradients in sedimentary basins. Geosci. Front. 14, 101685 (2023).

Brown. A. Formation of high helium gases: A guide for explorationists. In AAPG Annual Convention on Unmasking the Potential of Exploration & Production, 11–14 (2010).

Cherniak, D. J. et al. Diffusion of helium in zircon and apatite. Chem. Geol. 268, 155–166 (2009).

Gao, M. et al. An analysis of relationship between the microfracture features and mineral morphology of granite. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 4765731 (2021).

Song, F. et al. Granite microcracks: Structure and connectivity at different depths. J. Asian Earth Sci. 124, 156–168 (2016).

Ballentine, C. J. et al. Tracing fluid origin, transport and interaction in the crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 539–614 (2002).

O’Nions, R. K. & Oxburgh, E. R. Heat and helium in the earth. Nature 306, 429–431 (1983).

Oxburgh, E. R. & O’Nions, R. K. Helium loss, tectonics, and the terrestrial heat budget. Science 237, 1583–1588 (1987).

Chen, J. et al. Research status of helium resources in natural gas and prospects of helium resources in China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 32, 1436–1449 (2021) ((in Chinese)).

Mulaya, E. et al. Structural geometry and evolution of the Rukwa Rift Basin, Tanzania: Implications for helium potential. Basin Res. 34, 938–960 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Differential accumulation and distribution of natural gas and its main controlling factors in the Sinian Dengying Fm, Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2, 24–36 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Characteristics, genesis and accumulation history of natural gas in Hetianhe gasfield, Tarim Basin, China. Sci. China 51, 84–95 (2008).

Zhou, F. et al. Geochemical characteristics and origin of natural gas in the DongpingeNiudong areas, Qaidam Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 1, 489–499 (2016).

Liu, K. et al. Distribution characteristics and controlling factors of helium-rich gas reservoirs. Gas Sci. Eng. 110, 204885 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Henry’s law and accumulation of weak source for crust-derived helium: A case study of Weihe Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 5–6, 333–339 (2017) ((in Chinese)).

Yakutseni, V. P. World helium resources and the perspectives of helium industry development. Pet. Geol. Theor. Appl. Stud. 9, 1–22 (2014).

Han, W. et al. Characteristics of rare gas isotopes and main controlling factors of helium enrichment in the northern margin of the Qaidam Basin. China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 5, 299–306 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Finding of the Dongping economic Helium gas field in the Qaidam Basin, and Helium source and exploration prospect. Nat. Gas Geosci. 31, 1585–1592 (2020) ((in Chinese)).

Cao, Z. et al. The gas accumulation conditions of Dongping Niudong Slope area in front of Aerjin Mountain of Qaidam Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 24, 1125–1131 (2014) ((in Chinese)).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFA0719000), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (No. 2022NSFSC0182) and the Sichuan Provincial innovation and entrepreneurship training project for undergraduate (S202110622057). Thanks for the guidance and help of professor Ying Xue from Sichuan University. The Analytical & Testing Center Sichuan University and Sichuan University of Science & Engineering High Performance Computing Center are acknowledged for providing computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. Y., X. L. and J. C.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, and validation. X. L. and M. L.: methodology and validation. P. T.: software and data curation. J. C., B. Y. and H. X.: supervision, writing—review and editing, and project administration. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, B., Chen, J., Liu, X. et al. Adsorption behavior of helium in quartz slit by molecular simulation. Sci Rep 14, 18529 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69298-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69298-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Laboratory Investigation of Signature Gas Transport and Fractionation Behavior in Granite for Underground Nuclear Explosion Detection

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025)