Abstract

Axial displacement of prosthetic components is a major concern in implant dentistry, particularly during screw tightening. However, implant manufacturers provide different recommended torques for tightening implant prosthetic components, which can lead to errors in prosthesis fit before and after impression making. Implant–abutment connection angle or abutment geometries can affect axial displacement. This study aimed to compare the axial displacement between conventional and digital components based on the tightening torque and differences in the implant–abutment connection angles and geometries. The results showed that scan bodies with different implant-abutment connection geometries exhibited smaller axial displacement with increasing tightening torque than other prosthetic components. Except for the scan bodies, there was no difference in the axial displacement of prosthetic components when tightened with the same torque. However, regardless of the use of digital or conventional method of impression making, the axial displacement between the impression making component and the abutment when tightened to the recommended torques were significantly different. In addition, axial displacement was affected by the internal connection angle. The results of this study indicate that the tightening torque and geometry of prosthetic components should be considered to prevent possible misfits which can occur before and after impression making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prosthetic components of internal tapered conical connection (internal connection) implants undergo axial displacement when subject to compressive forces generated by screw tightening or occlusion1,2. Most of the axial displacement occurs during screw-tightening, and internal connection implants undergo more axial displacement than external connection ones3. There are three causes of axial displacement in internal connection implants: machining tolerance, the settling effect, and the wedging effect. Machining tolerance refers to the mechanical errors that occur during manufacturing of implant components, resulting in deviations from the intended dimensions4. The settling effect is evident between two surfaces with different roughness because of the rough surfaces becoming flatter and getting closer owing to repetitive friction5. Finally, the wedging effect is unique to internal connection implants and occurs when the abutment acts as a wedge, causing it to move in the direction of insertion as the tightening torque increases. The degree of wedging increases as the tightening torque increases, because of which axial displacement is greater in internal connection implants than in external connection implants6.

Axial displacement occurs not only in abutments but also in impression copings and scan bodies, which are used to record and transfer the position of the implant fixture in the gypsum model or scan file7. Implant impressions are recorded using two methods: conventional and digital. The conventional method involves connecting a pick-up or transfer impression coping to the implant8. When tightened at a torque of 30 Ncm, the axial displacement of two impression coping types was approximately 26.7 and 24.5 µm, respectively.2 Likewise, the digital method involves connecting a scan body to the implant9. When tightened at a torque of 5, 10 Ncm or hand tightening torque, the axial displacement of scan bodies can range from 20 µm to a maximum of 120 µm10. However, according to manufacturer's recommendations, impression copings and scan bodies are hand-tightened, whereas abutments are tightened at a torque of approximately 30 Ncm, resulting in a discrepancy and eventually a misfit of the implant prosthesis11.

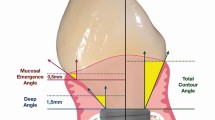

In addition, even the same prosthesis type can have different axial displacements depending on the structure of the implant-abutment connection. In addition to the external/internal connection, the structure of the implant-abutment connection can also differ in the geometry of the abutment and internal connection angle. While axial displacement due to the wedging effect is unique to internal conical connection (ICC) implants6, Kim et al. showed that even in ICC implants, the geometry of certain structures in scan bodies can prevent their vertical settling, similar to that in external connection implants, reducing the axial displacement10. Additionally, in internal conical connection implants, axial displacement is greater with smaller internal connection angles. Kim et al. reported that the smaller the internal connection angle, the greater the axial displacement3.

Many previous studies have compared the axial displacement of conventional prosthetic components based on the type of implant-abutment connection, tightening torque, and internal connection angle1,2. However, few studies have compared the axial displacement of digital components, including scan bodies, with those of conventional components or focused on the geometry of the implant-abutment connection. Comparing the axial displacement of the impression making components and the abutments as a function of the tightening torque can be a way to account for and prevent vertical errors that can occur during the impression making process. In addition, the inclusion of a digital component in the comparison allows us to see how the factors that affect axial displacement are different for digital and conventional methods. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to compare the axial displacement between conventional and digital prosthetic components based on the recommended torque and differences in the implant-abutment connection angles and geometries. The first null hypothesis is that there is no difference in axial displacement between the impression making components and the abutments caused by tightening torque. The second null hypothesis is that the axial displacements of the implant prosthetic components are not affected by the internal connection angle or the geometry of the abutments.

Methods

Implant fixtures

Two implant fixtures with different internal connection angles of 7° (IT implants, ø4.3 × 8.5, 7° internal octagonal connection, Warantec) and 11° (IU implants, ø4.5 × 8.5, 11° internal hexagonal connection, Warantec) were used (Fig. 1).

Implant prosthetic assemblies

Four types of implant prosthetic assemblies were used: impression copings and SB abutments for the conventional method and scan bodies and titanium base abutments (Ti-base abutments) for the digital method (Fig. 2). According to manufacturer's recommendations, impression copings and scan bodies should be tightened at a torque of 10 Ncm, whereas SB and Ti-base abutments should be tightened at a torque of 30 Ncm. Furthermore, no vertical stop is included in the pick-up impression coping, SB abutment, or Ti-base abutment, whereas it is present in the scan body, indicating a difference in the implant-abutment connection (Fig. 3).

Fabrication of experimental models

The implant fixtures were embedded in Type IV dental stone (GC Fujirock EP; GC Europe, Leuven, Belgium) to ensure that they could withstand the applied torque. The size of the experimental models was standardized at 10 mm × 10 mm × 8.5 mm to minimize errors during length measurements. Surveyors were used to position the implant fixtures perpendicular to the horizontal surface in the dental stone model. The completed experimental models were fixed to a grid to provide resistance to rotational forces by the applied torque (Fig. 4a, b, and c).

Measurement of axial displacement. (a) Surveyor used to ensure that the implant is perpendicular to the horizontal surface. (b) Implant embedded in a cubic gypsum model. (c) Distance from the bottom to the implant platform set at 8.5 mm. (d) Implant suprastructure connected by hand tightening. (e) Implant superstructures tightened using an auto torque driver. (f) Total length from the bottom to the top of the suprastructure measured using an electronic micrometer.

Measurement of axial displacement

After preparing the experimental models, the prosthetic components were tightened at a torque of 10 Ncm to simulate the hand torque, and the length was measured (L10) (Fig. 4d). Then, the tightening torque was increased to 25 Ncm, 30 Ncm, and 35 Ncm, respectively, and the length was measured for each torque level (Ltorque) (Fig. 4e). This was done to include the recommended torques for abutments from different implant manufacturers.

Length measurements were performed using an electronic micrometer to measure the distance from the bottom of the experimental model to the top of the prosthetic components (impression copings, scan bodies, or abutments). The axial displacement (Dtorque) was calculated by subtracting the measured length after torque application from the measured length at 10 Ncm torque (Ltorque–L10) and recorded in micrometers (Fig. 4f). The process of tightening and increasing the torque on the prosthetic components was performed by a single operator.

The difference in axial displacement (ΔD) within each group was calculated as follows:

For the conventional method, the axial displacements of the impression copings and SB abutments were compared.

For the digital method, the axial displacements of the scan bodies and Tibase abutments were compared.

For both the digital and conventional methods, when calculating the ΔDtorque at the recommended torque level, the impression coping and scan body are tightened as hand torque (or 10 Ncm), resulting in zero axial displacement. Therefore, the axial displacement of the SB abutment or Ti-base abutment directly corresponds to the ΔDtorque.

The axial displacement of two implant fixtures with different internal connection angles was compared at a all torque levels with identical prosthetic component.

Statistics

Statistical software program (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis. First, a paired t-test was used to analyze the statistical significance of axial displacement (Dtorque). Next, an independent t-test was used to compare the axial displacement (ΔDtorque) among different prosthetic assemblies for the same implant fixture. Lastly, an independent t-test was used to compare the axial displacement (ΔDtorque) based on the implant-abutment connection angles for the same prosthetic assembly. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Axial displacement based on tightening torque

The prosthetic assemblies were categorized into two groups, digital and conventional, and the results comparing axial displacement among the groups are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 5.

The axial displacement of the scan body was approximately 20–30 µm smaller than that of the impression coping, SB abutment, and Ti-base abutment. Specifically, not only was the axial displacement of the scan body small in absolute magnitude but also was the additive axial displacement small with increasing torque.

In the conventional group, the axial displacements of the impression coping and the SB abutment showed no or small differences when tightened at the same torque. In the 7° internal connection implant, the axial displacements of the impression coping and the SB abutment at a torque of 25 and 30 Ncm were significantly different (P < 0.05), but not at a torque of 35 Ncm (P < 0.05). For the 11° internal connection implant, the axial displacement did not differ significantly at any torque level (P > 0.05). However, when tightened at the recommended torque, the SB abutment showed more axial displacement than the impression coping.

However, in the digital group, a significantly greater difference in axial displacement between the scan body and Ti-base abutment was observed when tightened at the same torque, with Ti-base showing greater axial displacement (P < 0.001). Similarly, when tightened at the recommended torque, the Ti-base abutment showed greater axial displacement than the scan body.

Axial displacement based on the internal connection angle

A comparison of axial displacement based on the implant-abutment connection angle is shown in Table 2 and Fig. 6. At all torque levels, axial displacement was significantly greater in 7° internal connection implants than in 11° internal connection implants (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, significant differences were observed in the axial displacement between the impression making components and the abutments when tightened with the recommended torque; therefore, the first null hypothesis was rejected. Additionally, scan bodies with a vertical stop exhibited less axial displacement compared to other prosthetic components, and the axial displacement was significantly greater in 7° internal connection implants than in 11° internal connection implants; hence, the second null hypothesis was also rejected.

Previous research has shown that when implant prosthetic assemblies without a vertical stop are tightened at a torque of approximately 30 Ncm, they exhibit an average axial displacement of approximately 25 µm2. In this study, impression copings, SB abutments, and Ti-base abutments also showed axial displacements that corresponded with the reported values. However, scan bodies showed a displacement of 2 to 7 µm, approximately 20 µm less than that of other components, when tightened at 30 Ncm torque. As shown in the previous study, the axial displacement of scan bodies can vary according to the structure of the implant-abutment connection. Scan bodies can be categorized according to the presence or absence of a vertical stop. Kim et al. showed that scan bodies without a vertical stop showed significantly greater axial displacement10.

Ko et al. showed that when an abutment with a vertical stop is used with an internal connection implant, the axial displacement was similar to that with an external connection implant. This is because when an abutment with a vertical stop is screwed in, the vertical stop engages the implant fixture and prevents the abutment from moving in the apical direction12. Such abutments are also known as "the frictionless type," because of the absence of friction from the slope between the abutment and the fixture. Considering that not all scan bodies have a vertical stop, scan bodies without a vertical stop will have a similar tendency to other prosthetic assemblies.

According to manufacturer's recommendations, impression making components such as impression copings or scan bodies should be hand-tightened, but abutments such as SB or Ti-base abutments should be tightened at 30 Ncm torque. The reason for screwing the abutments at a greater torque (30 Ncm) than impression making components is to preload the screw, which increases the stability of the abutment-implant connection and prevents screw loosening13. Based on these facts, the notable aspect of this experiment is that the impression making component was tightened to 25, 30, and 35 Ncm rather than the recommended hand torque (or 10 Ncm). The first reason for this approach is that the implant-abutment connection structure of the impression making component differs from that of the abutment, so we wanted to observe the trend when tightened to the recommended torque levels for abutments. The second reason is that many previous studies have measured axial displacement at various torque levels within the 25–35 Ncm range2,14, and in clinical practice, when tightening prosthetic components with a torque wrench, it is applied as a range rather than an exact value; Therefore, we used an electronic device in the experiment to apply precise torque15,16.

A potential problem with tightening to the recommended torque is that it causes a difference in the axial displacement of the impression making component and the abutment, which can eventually lead to a misfit of the final prosthesis. The results of this study also show that tightening to the recommended torque can result in a misfit of 22–38 µm with the conventional method and 23–42 µm with the digital method. Considering that the thickness of the articulation paper and shim stock was 12–40 µm and 8 µm, respectively, the difference can be clinically significant17. More than just the need for occlusal adjustment, especially in cases with multiple implants, this misfit can negatively affect the passive fit of the prosthesis. A passive fit implies the absence of any no tension in the retaining screws when the prosthesis is connected to two or more implants18. A lack of passive fit of the definitive prosthesis may cause mechanical (screw loosening, screw fracture, or prosthesis fracture) or biological (mucositis or peri-implantitis) complications19. Therefore, if the fit obtained in the verification test is unsatisfactory, new impressions or corrections in the implant positions in the digital scan must be made20. Therefore, we cannot overlook the difference in axial displacement occurring before and after impression making.

With the conventional method, if impression copings are tightened at the same torque as SB abutments, the difference in axial displacement was within 8 µm, which is not statistically significant and might not be clinically significant. These results indicate that regardless of whether the component is an impression making component or an abutment, there is no difference in axial displacement with increasing tightening torque if there is no vertical stop in the implant-abutment connection. This finding is consistent with several studies that have investigated the subsidence associated with varying tightening torques of impression copings and abutments in internal connection implants2,21. Therefore, when making impressions using the conventional method, matching the tightening torque of the impression making component to that of the abutment may reduce misfits caused by differences in axial displacement. The reason this method can be useful is that, typically, to reduce misfit when taking impressions for implant prosthetics, the direct abutment-level impression method, similar to the impression technique used for natural teeth, is employed to prevent any axial displacement. However, this method can make it difficult to accurately capture the abutment margin and may require additional components22.

In contrast, with the digital method, the Ti-base abutment showed axial displacement approximately 20–30 µm greater than the scan body with a vertical stop, even when both components were tightened at the same torque. This difference was clinically and statistically significant. Reducing these errors is crucial for achieving a passive fit in single- or multiple-implant restorations23. With the conventional method, errors can occur at various stages, including the connection of the impression coping, laboratory analog connection, deformation of the impression material, and volumetric changes in the gypsum model24. However, with the digital method, the effect of axial displacement resulting from tightening of the scan body becomes more pronounced as several stages are omitted. Kim et al. showed that when implant prostheses are fabricated using the digital method, the accuracy is directly affected by the digital impression obtained through the intraoral scan, uneven application of powder, improper positioning of the intraoral scanner, and inadequate scan data, which can be the biggest sources of error25. However, to date, attempts to compensate for the errors introduced by axial displacement have been limited. Therefore, with the digital method, even if an accurate digital impression is obtained, the vertical error caused by the torque should be corrected by calculating the expected errors and applying corrections in the software.

Regarding the implant-abutment connection angle, prosthetic components with the 7° internal connection implant showed a larger axial displacement than those with the 11° internal connection implant. An ICC implant has a tapered interference fit, also known as a Morse taper, which results in axial displacement when axial loads, such as a tightening torque or occlusal forces, are applied. The taper angle, contact length, inner and outer diameters of the contacting members, insertion depth, material properties, and coefficient of friction can affect the extent of axial displacement. Bozkaya et al. showed that as the internal taper angle of the implant increases, the resistance to axial loading at the contact surface increases, which may explain the relatively smaller axial displacement26.

In this study, only scan bodies with vertical stops from a single company were used. Therefore, including scan bodies from various companies and those without a vertical stop would provide more analytical results regarding the axial displacement of scan bodies according to the tightening torque. Additionally, because only the tightening torque was considered a factor affecting axial displacement, it was necessary to consider cyclic loading while exploring solutions for axial displacement.

On the clinical side, difference in axial displacement between prosthetic components that occur during impression making can lead to prosthetic mis-fit and require additional modifications. Studies have shown that equalizing the tightening torque of the impression making components and abutments can reduce the difference in axial displacement. However, if the impression making component, such as the scan body, has a vertical stop, equalizing the tightening torque would be useless and require additional modifications in other ways.

Conclusion

This study evaluated axial displacement of implant prosthetic assemblies at the recommended torque and according to implant-abutment connection angles and geometries.

Within the limitations of this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

The axial displacement of scan bodies with a vertical stop, when tightened to 30 Ncm, was approximately 2 to 7 µm, which is about 20 µm smaller compared to other prosthetic components without a vertical stop.

-

2.

Regardless of the use of digital or conventional method, if the prosthetic component is tightened to the recommended torque, the axial displacement is approximately 22 to 42 µm greater in impression making components tightened by hand torque (or 10 Ncm) compared to abutments tightened to 25 to 35 Ncm.

-

3.

When tightened to the same torque, the axial displacement of all prosthetic components was greater in 7° internal connection implants than in 11° internal connection implants.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Seol, H. W. et al. Axial displacement of external and internal implant-abutment connection evaluated by linear mixed model analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 30(6), 1387–1399 (2015).

Lee, J. H. et al. Axial displacements in external and internal implant-abutment connection. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 25(2), e83–e89 (2014).

Kim, K. S. & Lim, Y. J. Axial displacements and removal torque changes of five different implant-abutment connections under static vertical loading. Materials (Basel) 13(3), 699 (2020).

Ma, T., Nicholls, J. I. & Rubenstein, J. E. Tolerance measurements of various implant components. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 12(3), 371–375 (1997).

Winkler, S. et al. Implant screw mechanics and the settling effect: Overview. J. Oral Implantol. 29(5), 242–245 (2003).

Merz, B. R., Hunenbart, S. & Belser, U. C. Mechanics of the implant-abutment connection: An 8-degree taper compared to a butt joint connection. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 15(4), 519–526 (2000).

Dellinges, M. A. & Tebrock, O. C. A measurement of torque values obtained with hand-held drivers in a simulated clinical setting. J. Prosthodont. 2(4), 212–214 (1993).

Chee, W. & Jivraj, S. Impression techniques for implant dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 201(7), 429–432 (2006).

Marques, S. et al. Digital impressions in implant dentistry: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(3), 1020 (2021).

Kim, J., Son, K. & Lee, K. B. Displacement of scan body during screw tightening: A comparative in vitro study. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 12(5), 307–315 (2020).

Dailey, B. et al. Axial displacement of abutments into implants and implant replicas, with the tapered cone-screw internal connection, as a function of tightening torque. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 24(2), 251–256 (2009).

Ko, K. H. et al. Axial displacement in cement-retained prostheses with different implant-abutment connections. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 34(5), 1098–1104 (2019).

Byrne, D. et al. Preloads generated with repeated tightening in three types of screws used in dental implant assemblies. J. Prosthodont. 15(3), 164–171 (2006).

Dincer Kose, O. et al. In vitro evaluation of manual torque values applied to implant-abutment complex by different clinicians and abutment screw loosening. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 7376261 (2017).

Jaarda, M. J., Razzoog, M. E. & Gratton, D. G. Providing optimum torque to implant prostheses: A pilot study. Implant Dent. 2(1), 50–52 (1993).

Sameera, Y. & Rai, R. Tightening torque of implant abutment using hand drivers against torque wrench and its effect on the internal surface of implant. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 20(2), 180–185 (2020).

Harper, K. A. & Setchell, D. J. The use of shimstock to assess occlusal contacts: A laboratory study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 15(4), 347–352 (2002).

Al-Meraikhi, H. et al. In vitro fit of CAD-CAM complete arch screw-retained titanium and zirconia implant prostheses fabricated on 4 implants. J. Prosthet. Dent. 119(3), 409–416 (2018).

Buzayan, M. M. & Yunus, N. B. Passive fit in screw retained multi-unit implant prosthesis understanding and achieving: A review of the literature. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 14(1), 16–23 (2014).

Gómez-Polo, M. et al. Guided implant scanning: A procedure for improving the accuracy of implant-supported complete-arch fixed dental prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 124(2), 135–139 (2020).

Gehrke, S. A. et al. Effects of different torque levels on the implant-abutment interface in a conical internal connection. Braz. Oral Res. 30, 1–9 (2016).

Kutkut, A., Abu-Hammad, O. & Frazer, R. A simplified technique for implant-abutment level impression after soft tissue adaptation around provisional restoration. Dent. J. (Basel) 4(2), 14 (2016).

Michalakis, K. X., Hirayama, H. & Garefis, P. D. Cement-retained versus screw-retained implant restorations: A critical review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 18(5), 719–728 (2003).

Taylor, T. D., Agar, J. R. & Vogiatzi, T. Implant prosthodontics: current perspective and future directions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 15(1), 66–75 (2000).

Kim, J. H. et al. Quantitative evaluation of common errors in digital impression obtained by using an LED blue light in-office CAD/CAM system. Quintessence Int. 46(5), 401–407 (2015).

Bozkaya, D. & Müftü, S. Mechanics of the tapered interference fit in dental implants. J. Biomech. 36(11), 1649–1658 (2003).

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021R1I1A1A01052695). This study was supported by a faculty research grant from Yonsei University College of Dentistry (6-2015-0101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. planned experiment, carried out experiment, data analysis, took photographs, drafted the original manuscript. S.K. helped coordinate the study and provided feedback on the results. J.P. and S.P. conceived the concept and did critical revision on the manuscript. J.C. coordinated the study, planned experiment, supervised the project and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have provided consent for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Back, S., Kim, S., Park, J. et al. Comparative study of axial displacement in digital and conventional implant prosthetic components. Sci Rep 14, 19185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69300-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69300-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical effects of taper angles in implant–abutment connection: a finite element study

International Journal of Implant Dentistry (2026)