Abstract

Piezoelectricity in quantum rare-earth metallic boron oxides with the coupling between magnetic, electric and elastic subsystem is studied theoretically. It is proved that the change of piezoelectric modules of the considered crystals are proportional to components of the quadrupole susceptibility, which determines the external magnetic and electric fields, strain and temperature dependences of that change. We show why holmium compounds manifest the strongest renormalization among other rare-earth ions in this family of crystals. The reason is in the structure of the low energy term of the electron configuration, depending on spins and orbital moments of 4f electrons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magneto-electric, piezoelectric and magneto-mechanic effects attract much attention of researchers. The interest to the studies of such effects is stimulated by two reasons. First, these effects are interesting of their own as the manifestation of the interaction between several degrees of freedom in physical systems. Second, maybe more important, these effects are used in a number of practical applications in the modern technique, where it is often necessary to govern some properties of devices by changing various external parameters. Piezoelectricity is one of the most known and developed branches of physics, where electric and elastic degrees of freedom are strongly inter-related. Piezoelectric materials are used in a number of applications, e.g., in the production of piezosensors, transducers, relaxators, piezoelectric cables, filters, actuators, generators, stabilizators, transformators, motors, etc. Last decades piezoelectricity is widely used in microelectronics, in particular in microelectromechanical systems, including biomedical ones. The most popular subjects for the manifestation of magneto-electro-mechanic effects are so-called multiferroics, which reveal both magnetic and ferroelectric properties see, e.g.,1,2,3,4,5. Notice that multiferroics are magnetically and electrically ordered systems. However, it is clear from general grounds that similar effects can exist in magnetic systems without magnetic and electric ordering, i.e., in quantum paramagnets. The effects of interaction of magnetic degrees of freedom and piezoelectricity in quantum systems with localized energy levels can be useful for the modern laser technique and for the regulation of quantum computers.

The goal of the present study is to find the effect of the renormalization of piezoelectric characteristics due to the coupling between the electric, magnetic and elastic subsystem of the quantum paramagnetic compound. Namely, we investigate the rare-earth based trigonal crystals with non-centersymmetric symmetry of the lattice. Such a symmetry permits piezoelectricity in the system. On the other hand, non-magnetic surrounding of magnetic ions determines the crystalline electric field, which acts on the latter, and, together with the spin-orbit interaction, affects the spin subsystem. This way the interaction between the spin, charge and elastic subsystems of the crystal changes piezoelectric characteristics of the quantum paramagnet. Using exact diagonalization of Hamiltonian matrix we calculate how such an interaction can be observed in the temperature, external magnetic and electric fields, and strain dependencies of the piezoelectric modules of the studied system.

Method

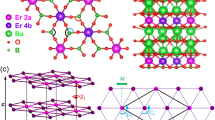

As the main subject we consider rare-earth metallic boron oxides (also known as metal borates). Metallic boron oxides \(\hbox {RMe}_{{3}}\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_{4}\) with R being the rare-earth or yttrium ion, and Me=Al,Ga,Sc,Cr,Fe are non-centersymmetric crystals (with the structure of the natural mineral huntite \(\hbox {CaMg}_{{3}}\)(\(\hbox {CO}_3)_{4}\)6) belonging to the trigonal space group R32 at high temperatures7,8. Some compounds of that family manifest structural phase transition at low temperatures to the monoclinic phase. In our study we concentrate on nonmagnetic Me ions, like aluminium and gallium, to avoid magnetic ordering effects.

The metallic boron oxides belong to the class of piezoelectrics, i.e., the stress \(\sigma _k\), \(k=1,\dots , 6\), causes the electric polarization \(P_j =d_{jk}\sigma _k\) with \(j= 1,2,3\equiv x,y,z\), (the direct piezoelectric effect), where \(d_{jk}\) is the tensor of piezoelectric modules. Here and below we use the Voight notations \(1=xx\), \(2=yy\), \(3=zz\), \(4=xz\), \(5=yz\), and \(6=xy\), symmetric with respect to index commutation. It is possible to reformulate the piezoelectric response as a function of the strain \(u_l\) (\(l=1,\dots ,6\)) as \(P_j = e_{jl}u_l\), where according to the Hooke law \(\sigma _k=C_{kl}u_l\). Here \(C_{kl}\) is the tensor of elastic modules, symmetric with respect to index commutation. This is why the piezoelectric tensor is \(e_{jl} =d_{jk}C_{kl}\). For most of the representatives of the family the local symmetry of R ion surrounding is \(\hbox {D}_3\)9. For such systems the piezoelectric response is determined by only two independent components of the piezoelectric tensor \(d_{jk}\)10, namely \(d_{11}\) and \(d_{14}\). There are six independent elastic modules for the \(\hbox {D}_3\) symmetry class. To remind, for that symmetry one has the connection \(2C_{66} =C_{11} -C_{12}\), \(C_{11}=C_{22}\), \(C_{24}=-C_{14}\), \(C_{55}=C_{44}\), and \(C_{56}=C_{14}\)11. Then the Hamiltonian of the interaction between the external electric field \(E_j\) (\(j=x,y\)) and the strain \(u_l\) is

where \(e_{11} =-e_{26}= -d_{11}C_{66}\), \(e_{14}=-e_{25} = -d_{11}C_{14}\), \(e_{15} =e_{24}=-d_{14}C_{44}\), and \(e_{21}= d_{14}C_{14}\), i.e., there are four independent components of the piezoelectric tensor \(e_{jl}\).

Let us consider rare-earth ions in the \(\hbox {D}_3\)-symmetric situation (to remind, we limit ourselves with the non-magnetic Me ions). Such crystals, for example, \(\hbox {YAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) and \(\hbox {GdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) doped with rare-earth ions and \(\hbox {RAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) systems themselves are used in optical devices (for self-frequency doubling and self-frequency summing lasers12,13,14,15,16,17), for mini- and microchip lasers17,18, and nonlinear optical crystals18,19). For all these quantum optical applications it is very important to use the possibility of governing of characteristics of the paramagnetic crystal by external fields and strains. Large orbital moments and the weak quenching of those moments of 4f electrons of rare-earth ions, the low-symmetric crystalline electric field and the weak interaction between localized 4f electrons (comparing to the interaction between 3d electrons of transition metals) imply the single-ion nature of magneto-electro-elastic effects in these systems, comparing to transition metal compounds, in which inter-ion mechanism dominates. On the other hand, such systems mostly do not order magnetically down to the lowest temperatures (of order of 0.5 K).

The Hamiltonian of the 4f electrons of rare-earth ions in the trigonal crystalline electric field \(B_p^q\) can be written as20

where \(O_p^q\) are the Stevens equivalent operators, \(a_{20} = 1/2\), \(a_{40} = 1/8\), \(a_{43} = \sqrt{35}/2\), \(a_{60} = 1/16\), \(a_{63} = \sqrt{105}/8\), \(a_{66} = \sqrt{231}/16\)21, \(\alpha _J\), \(\beta _J\) and \(\gamma _J\) are the Stevens coefficients, \(g_J\) is the Landée g-factor, \(\mu _B\) is the Bohr magneton, \(J_{x,y,z}\) are the operators of the projections of the total moment of the 4f configuration of electrons of rare-earth \(\hbox {R}^{3+}\) ions, and \(\textbf{H}\) is the external magnetic field. 4f electrons of rare-earth ions can interact with the external electric field and the strain of the crystal lattice. For our purpose we consider the Hamiltonian of such an interaction

where \(a_{21}=\sqrt{6}\), \(a_{22}=\sqrt{6}/2\), and

here \((B_2^{1,2})^0\) (\(({{\tilde{B}}}_2^{1,2})^0\)) are the components of the possible internal crystalline electric field of the monoclinic symmetry, and the parameters \(A_{jl}\) or \({{\tilde{A}}}_{jl}\) (\(j,l=1,2\)), and \(b_k\) (\(k=1,4,5,6\)) are the components of tensors of the magneto-electric and magneto-elastic interactions. The nature of those interactions is following: The crystalline electric field of ligands, caused by lattice strains, and the external electric field act on the orbital moment of 4f electrons, and, due to the spin-orbit coupling, affect the spin degrees of freedom of 4f electrons.

Then we obtain for the effective piezoelectric modules of the rare-earth metallic boron oxides \(e_{jk}^{eff} = e_{jk} +(\alpha _J/2) b_k a_{2q}(\partial Q_{2}^q/\partial E_{j})\), where \(Q_{2}^q = \langle O_{2}^{q} \rangle\) (\(q=1,2\)) is the component of the expectation value of the related Stevens operator. It is clear that \(Q_{2}^q\) have the meaning of the components of the tensor of quadrupole operators. According to the above, \((\partial Q_2^q/\partial E_j) = (\alpha _J/2)a_{2q}A_{jq} \chi _2^q\), where \(\chi _{2}^q = \partial Q_{2}^q/\partial B_{2}^{q}\) is the component of the quadrupole susceptibility. Hence, the relative changes of the piezoelectric modules caused by the interaction with 4f electrons of rare-earth ions are proportional to the components of the quadrupole susceptibility of 4f electrons

For example, the \(e_{11} =-e_{26}\) and \(e_{14}=-e_{25}\) components of the piezoelectric tensor are \(e_{11}^{eff} = e_{11} +(\alpha _J^2a_{22}^2/4)A_{12}b_1\chi _2^2\), and \(e_{14}^{eff} = e_{14} +(\alpha _J^2a_{21}^2/4) A_{11}b_4\chi _2^1\).

The dependencies of the components of the quadrupole susceptibility can be obtained from the free energy of the system with the Hamiltonian \({{H}}_{cf}+{{{H}}}_{int}\). In our numerical calculations we used several sets of values of the crystalline electric fields \(B_p^q\) for rare-earth metallic boron oxides, estimated from optical studies, see, e.g.,22,23,24,25,26,27. To check our calculations we also compared our results, which show good agreement with the known from experiments data for the behavior of the specific heat, magnetic moment, and the electric polarization for rare-earth metallic boron oxides.

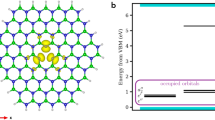

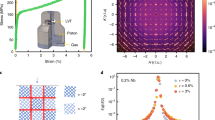

Let us start our consideration with \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), as the most interesting compound, see below. For the 4\(f^{10}\) electrons (\(^5I_8\) term) of \(\hbox {Ho}^{3+}\) ion the values of the Stevens coefficients are \(\alpha _J =-1/(2\cdot 3^2 \cdot 5^2)\), \(\beta _J =-1/(2\cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7 \cdot 11\cdot 13)\), and \(\gamma _J =-5/(3^3 \cdot 7 \cdot 11^2\cdot 13^2)\), the Landée factor is \(g_J=5/4\). The best fitting set of the values of the crystalline electric field is \(B_2^0= 667\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^0= -1610\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^3= -345\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^0= 95\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^3= -405\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), and \(B_6^6= -660\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). With that set of parameters the eigenvalues of \({H}_{cf}\) for \(\textbf{H}=\textbf{E} =u_p=0\) are [\(\hbox {0}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {8.72}^{(d)}\), 24.87, 32.8, 112.6, \(\hbox {156.7}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {258.9}^{(d)}\), 309, \(\hbox {363.69}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {421.91}^{(d)}\), 445.6] \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) (the index (d) defines degenerate dublets, the energies are measured from the lowest level). Using these results we calculate the behavior of the quadrupole susceptibility \(\chi _2^2\), and compare it’s magnetic field dependence with the observed in29 magnetic field behavior of the component of the piezoelectric modulus \(e_{11}\) at \(T=1.7\) K. The best fit is presented in Fig. 1a. To obtain that fit we had to introduce nonzero values of the components of the crystalline electric field \((B_2^1)^0 = -4\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) and \((B_2^2)^0 = 6\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). Those small values (of order of several % of the values of the crystalline electric field of the trigonal set) can be caused by small domains of the monoclinic phase present in the specimens of \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) used in the low temperature experiment29. In our calculations we take into account the hyperfine coupling of the total moment of the \(\hbox {Ho}^{3+}\) ion with the spin of Ho nucleus \(S=7/2\). The energy of the hyperfine coupling was 0.027 \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\)28. The results of the low temperature (\(T=0.1\) K) magnetic field behavior of \(\chi _2^2\) and \(\chi _2^1\) as functions of \(B_2^2\) and \(B_2^1\) (to remind, they also depend on the external electric field components \(E_{x,y}\) and on the strains \(u_{1,2,4,5,6}\)) are shown in Fig. 1c,d. To get the values for the piezoelectric modulus \(e_{11}\) it is necessary to introduce the normalization multiplier \(e_{11}(H=0)/\chi _2^2(H=0) = 1720.3\) K \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\)/\(\hbox {m}^2\). We can see that the external magnetic field can drastically change the value of the piezoelectric effect in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\). Notice that the hyperfine interaction enhance the external fields’ and strains’ effect on the quadrupole susceptibility at low temperatures. The reason for drastic changes at \(H \sim 2\) T is clear from Fig. 1b: at that value of the field the crossover of low-energy levels takes place.

(a) The dependencies of piezoelectric modulus \(e_{11}\) on the magnetic field \(H\parallel x, H\parallel y\). The boxes are the data of the experiment29. Solid line corresponds to the optimal fit, \(T=1.7\) K. (b) Low-energy part of the spectra as a function of the external magnetic field (\(H\parallel x\) and \(H\parallel y\)) of \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\). (c) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^1\) on \(B_2^1\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K. (d) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^2\) on \(B_2^2\) and \(H\parallel y\) in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K.

In Fig. 2 we show the calculated behavior of the component of the quadrupole susceptibility for \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) at \(T=1\) K (panel a), and \(T=4.2\) K (panel b). We see that with the growth of the temperature the external fields and strain dependencies of the quadrupole susceptibility become more smooth. We have also performed calculation of related components of the quadrupole susceptibility for all magnetic ions of the family \(\hbox {RAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), for which the estimations of the crystalline electric field values are known (the results will be published elsewhere). As a typical example, Fig. 3d, shows the low temperature magnetic and crystalline field behavior of \(\chi _2^2\) for \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) (4\(f^3\) electrons, the \(^4I_{9/2}\) term, nuclear spin zero). The used set for the crystalline electric field values for \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) is: \(B_2^0= 452\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^0= -1516\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^3= -945\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^0= 514\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^3= -245\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), and \(B_6^6= -427\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). The Stevens coefficients are \(\alpha _J =-7/(3^2 \cdot 5)\), \(\beta _J =- 2^3\cdot 17/(3^3 \cdot 11^3 \cdot 13)\), and \(\gamma _J =-5\cdot 17\cdot 19/(3^3 \cdot 7 \cdot 11^3\cdot 13^3)\); the Landée g-factor is \(g_J= 8/11\)20. The corresponding calculated energy levels of \({{\mathcal {H}}}_{cf}\) at \(\textbf{H}=\textbf{E}=u_p=0\) are [\(\hbox {0}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {738.8}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {1289.6}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {1825.7}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {2187.2}^{(d)}\)] \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). We see that \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) does not manifest the magnetic and effective electric field dependence (for realistic values of the magnetic and electric fields and strains). From our results similar behavior is seen for other rare-earth ions (except of Tm\(^{3+}\), the 4\(f^{12}\) electrons, \(^3H_6\) term). For \(\hbox {TmAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) the used set of crystalline electric field values was: \(B_2^0= 561\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^0= -938\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_4^3= -475\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^0= 540\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), \(B_6^3= -137\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), and \(B_6^6= 575\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) (we used the data of optical experiments, see, e.g.,30), the Stevens coefficients and the Landée g-factor are \(\alpha _J =1/(3^2 \cdot 11)\), \(\beta _J =2^3/(3 \cdot 5 \cdot 11^2)\), \(\gamma _J =-5/(3^4 \cdot 7 \cdot 11^2\cdot 13)\), and \(g_J = 7/6\)20. The calculated energy levels of \({{{H}}}_{cf}\) at \(\textbf{H}=\textbf{E}=u_p=0\) are [\(\hbox {0, 26.9}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {93.5}^{(d)}\), 148.1, 252.7, 293.0, 301.2, \(\hbox {384.8}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {496.8}^{(d)}\)] \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). Notice, however, that for \(\hbox {TmAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) the calculated changes of the quadrupole susceptibilities caused by the external fields and strains were about 3-4 times smaller than for \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) (see Fig. 3c).

(a) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^1\) on \(B_2^1\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=1\) K. (b) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^1\) on \(B_2^1\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=4.2\) K. (c) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^1\) on \(B_2^1\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {HoGa}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K. (d) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^2\) on \(B_2^2\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {HoGa}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K.

(a) Low-energy part of the spectra as a function of the effective crystalline electric field parameters (\(B_2^1\) and \(B_2^2\)) of \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(H_x=1\) T. (b) Low-energy part of the spectra as a function of the effective crystalline electric field parameters (\(B_2^1\) and \(B_2^2\)) of \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(H_x=1\) T. (c) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^1\) on \(B_2^1\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {TmAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K. (d) The calculated dependence of the quadrupolar susceptibility \(\chi _2^2\) on \(B_2^2\) and \(H\parallel x\) in \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), \(T=0.1\) K.

What is the reason for such a strong dependence of the renormalization of the piezoelectric modules for Ho aluminium boron oxide, and small enough dependence for compounds of that family with other rare-earth ions? To answer that question we plot the low-energy part of \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) energy spectra as function of the external magnetic field \(H_{x,y}\) (Fig. 1b) and \(B_2^{1,2}\) (Fig. 2a), and we plot similar dependence on \(B_2^{1,2}\) for \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) (Fig. 2b); the dependence of \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) energy levels as the function of external magnetic field is almost absent too, so we do not present it. One can see that for \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) the energies of the lowest levels strongly depend on \(H_{x,y}\) and \(B_2^j\), while for \(\hbox {NdAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) the levels are almost insensitive to external fields and strains of realistic for experiments values (we have also checked it for \(H_{z}\) and for other R ions). For \(\hbox {TmAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) the lowest energy levels do manifest the dependence on external fields and strains, however that dependence is weaker than for \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\), see Fig. 2c. We can conclude that the strongest magnetic field dependence of the piezoelectric modules exists for Ho ion. Why is it so? On the one hand, we checked that the values of the trigonal crystalline electric fields in all \(\hbox {RAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) are relatively close to each other and cannot themselves be the reason for such a dramatic difference in the behavior. Notice that the ionic radia of rare-earth ions decrease with the number of electrons in 4f configuration, and from that viewpoint \(\hbox {Ho}^{3+}\) should not be very different from, e.g., \(\hbox {Er}^{3+}\). Also, the total moment of 4f electrons of \(\hbox {Tm}^{3+}\) (\(J=6\)) is the same as the one for \(\hbox {Tb}^{3+}\), however, the calculated fields and strain dependence of the low-energy spectra and, hence, the quadrupole susceptibilities and related piezoelectric modules drastically differ from each other for aluminium boron oxides with those ions. Therefore, we conclude that the difference is caused by the different values of Stevens’ coefficients \(\alpha _J\), \(\beta _J\), and \(\gamma _J\), which relate the components of the crystalline ligand potentials with the equivalent moment operators. Those coefficients depend not only on the values of the total moment of the configuration J, but also on the values of spins and orbital moments of electrons of the electron configuration. For \(\hbox {Ho}^{3+}\) ion the electron configuration is such that there exist low energy levels, which are affected by the external fields and strains. We have also calculated the dependencies of the quadrupole susceptibilities for \(\hbox {HoGa}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) using the data of optical experiments in that compound, see, e.g.,31,32. The calculated energy levels of \({{ {H}}}_{cf}\) at zero external fields and strains for \(\hbox {HoGa}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\) are: [\(\hbox {0}^{(d)}\), 9.9, \(\hbox {12.4}^{(d)}\), 31.1, 96.8, \(\hbox {149.9}^{(d)}\), 202.5, \(\hbox {233.8}^{(d)}\), \(\hbox {274.9}^{(d)}\), 298.3, \(\hbox {311.1}^{(d)}\)] \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). The results are shown in Fig. 2c,d. One can see that for this compound the expected influence of the external magnetic and electric fields and strains on the piezoelectric effect can be even stronger than for \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\).

Conclusion

In summary, we have calculated how the external magnetic and electric fields and strains can affect piezoelectric modules for rare-earth metallic boron oxides. We have shown that the strongest effects are expected for crystals with holmium. We have checked that the main reason for such a distinguished behavior of \(\hbox {Ho}^{3+}\) ion is in the structure of its’ low energy electron configuration. The same reason causes the strongest magneto-electric effect observed in \(\hbox {HoAl}_3\)(\(\hbox {BO}_3)_4\)33, comparing to other representatives of that group of compounds (the results of calculations will be presented elsewhere).

Our research has shown that rare-earth metallic boron oxides are promising compounds for creating various new piezoelectric devices based on quantum principles. For example, due to the interaction between the electric, elastic and magnetic subsystems, these compounds can be considered as material for different electrical gates controlled by stress and the magnetic field34,35. Another area of application is nonlinear optics devices, first of all the devices for frequency doubling of the electromagnetic oscillations—second harmonics generation36,37.

However, the most promising area of application is the creation of new elements for quantum computers. Actually, unlike multiferroics, phase transitions to magnetically ordered phase in considered compounds are absent down to low temperatures region (at least, holmium and a number of other rare-earth ions remain in the paramagnetic phase in the low temperature limit). Consequently, discrete energy spectrum of these rare-earth ions are preserved at least down to ultra-low temperatures. At the same time, in contrast to dilute borates, which also demonstrate paramagnetic low temperatures properties, the considered compounds have the highest possible concentration of magnetically active ions per structural unit and, hence, the magnitudes of the observed effects are maximal. All this allows us to consider rare-earth metallic boron oxides as candidates for creating the qubits of a radically new type. Actually, in quantum computer qubits perform two functions. The first, a qubit stores an information (quantum state) and the second, the interaction of a qubit with an external control device causes manipulation of information (transformation of a quantum state). Storage of the information requires minimization of the qubit interaction with the environment (to minimize the destructive interference), but the manipulation of a qubit state requires interaction with control device (i.e. with the environment). Thus, qubits design requires the simultaneous fulfilment of two mutually exclusive conditions: one needs to minimize the interaction of a qubit with the environment, and it is necessary to preserve such an interaction to be small but finite. In the proposed qubit, due to the presence of the interaction among the electrical, magnetic and elastic subsystems, one can provide mechanical switching “on” and “off’ the interaction between the qubit and the environment using, e.g., the regular piezoelectric effect. There are no additional control elements (capacitive, inductive, etc.) required.

Data availibility

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Fiebig, M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 38, R123–R152 (2005).

Eerenstein, W., Mathur, N. D. & Scott, F. J. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 442, 759–765 (2006).

Tokura, Y. Multiferroics—Toward strong coupling between magnetization and polarization in a solid. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 310, 1145–1150 (2007).

Wang, K., Liu, J.-M. & Ren, Z. Multiferroicity: The coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 58, 321–448 (2009).

Spaldin, N.A. & Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 18, 203–212 (2019).

Dollase, W. A. & Reeder, R. J. Crystal structure refinement of huntite, \(\text{ CaMg}_3\)(\(\text{ CO}_3)_4\), with X-ray powder data. Am. Mineral. 71, 163–166 (1986).

Joubert, J. C., White, W. B. & Roy, R. Synthesis and crystallographic data of some earth-iron borates. J. Appl. Cryst. 1, 318–319 (1968).

Campa, J. A. et al. Crystal structure, magnetic order, and vibrational behavior in iron rare-earth borates. Chem. Mater. 9, 237–240 (1997).

Chong, S., Riley, B. J., Nelsona, Z. J. & Perry, S. N. Crystal structures and comparisons of huntite alumnium borates \(\text{ REAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) (RE = Tb, Dy and Ho). Acta Cryst. E76, 339–343 (2020).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Electrodynamics of Continuous Media (Pergamon Press, 1984).

Truell, R., Elbaum, C. & Chick, B. B. Ultrasonic Methods in Solid State Physics (Academic Press, 1969).

Bartschke, J., Knappe, R., Boller, K.-J. & Wallenstain, R. Investigation of efficient self-frequency-doubling Nd:YAB. IEEE J. Quant. Electron. 12, 2295–2300 (1997).

Wang, P., Dawes, J. M., Dekker, P. & Piper, J. A. Highly efficient diode-pumped ytterbium-doped yttrium aluminium borate laser. Opt. Commun. 174, 467–470 (2000).

Jaque, D. Sef-frequency sum-mixing in Nd dopped nonlinear crystals for laser generation in the three fundamental colours: The NYAB case. J. All. Comp. 323–324, 204–209 (2001).

Dekker, P. et al. Widely tunable yellow-green lasers based on the self-frequency-douling material Yb:YAB. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 20, 706–712 (2003).

Brenier, A., Tu, C., Zhu, Z. & Wu, B. Red-green-blue generation from a lone dual-wavelength \(\text{ GdAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\): \(\text{ Nd}^{3+}\) laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 2034–2036 (2004).

Chen X., Luo Z., Jaque D., Romero J.J., Garcia Sole J., Huang Y., Jiang A. & Tu J. Comparison of optical spectra of Nd\(^{3+}\) in \(\text{ NdAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) (NAB), Nd:\(\text{ GdAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) (NGAB) and ND:\(\text{ Gd}_{0.2}\text{ Y}_{0.8}\text{ Al}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) (NGYAB) crystals J. Phys. :Cond. Mat. 13, 1171-1178 (2001).

Huang, Z., Gong, X., Huang, Y. & Luo, Z. Modelling of the fundamental continuous wave Yb\(^{3+}\):\(\text{ YAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) microchip laser. Opt. Commun. 237, 389–397 (2004).

Jiang, H. D. et al. Growth of Yb: \(\text{ YAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) crystals and their optical and self-frequency-doubling properties. J. Crystal Growth 233, 248–252 (2001).

Abragam, A. & Bleaney, B. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Transition Ions (Clarendon Press, 1970).

Aminov, L. K., Malkin, B. Z. & Teplov, M. A. Magnetic properties of nonmetallic lanthanide compounds. in Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths 22, 295–506 (Elsevier1996).

Neogy, D., Chattopadhyay, K. N., Chakrabarti, P. K., Sen, H. & Wanklyn, B. M. Studies of the magnetic behaviour of \(\text{ ErAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) and the effects of the crystal field. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 59, 783–787 (1998).

Cascales, C., Zaldo, C., Caldiño, U., Garcýa-Solé, J. & Luo, Z. D. Crystal field analysis of Nd\(^{3+}\) energy levels inmonoclinic \(\text{ NdAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) laser. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 12, 8071–8085 (2001).

Cavalli, E. et al. Optical spectroscopy and crystal-field analysis of \(\text{ YAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) single crystals doped with dysprosium. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 15, 1047–1056 (2003).

Dominiak-Dzik, G., Solarz, P., Ryba-Romanowski, W., Beregi, E. & Kovács, L. Dysprosium-doped \(\text{ YAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) (YAB) crystals: an investigation of radiative and non-radiative processes. J. All. Comp. 359, 51–58 (2003).

Martínez Vázquez R., Osellame R., Marangoni M., Ramponi R., Diéguez E., Ferrari M. & Mattarelli M. Optical properties of \(\text{ Dy}^{3+}\) doped yttrium-aluminium borate. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 16, 465-471 (2004).

Kebaili, I., Dammak, M., Cavalli, E. & Bettinelli, M. Spectra energy levels and symmetry assignments of Sm\(^{3+}\) doped in \(\text{ YAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\) single crystal. J. Luminesc. 132, 2092–2097 (2012).

Baraldi, A. et al. Hyperfine interactions in \(\text{ YAB:Ho}^{3+}\): A high-resolution spectroscopy investigation. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165130 (2007).

Bilych I.V., Kololodyazhnaya M.P., Zhekov K.R., Zvyagina G.A., Fil V.D. & Gudim I.A. Elastic, magnetoelastic, magnetopiezoelectric, and magnetodielectric characteristics of the \(\text{ HoAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\), Fiz. Nizk. Temp. 46, 1092-1101 (2020) [Low Temp. Phys. 46, 923-931 (2020)].

Jia, G. et al. Growth and thermal and spectral properties of a new nonlinear optical crystal \(\text{ TmAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\). Crystal Growth Design 5, 949–952 (2005).

Blasse, G. & Bril, A. Crystal structure and fluorescence of some lanthanide gallium borates. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 29, 266–267 (1967).

Kim, K., Moon, Y. M., Choi, S., Jung, H. K. S. & Nahm, S. Luminescent properties of a novel green-emitting gallium borate phosphor under vacuum ultraviolet excitation. Mater. Lett. 62, 3925–3927 (2008).

Liang, K.-C. et al. Giant magnetoelectric effect in \(\text{ HoAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3\))\(_4\). Phys. Rev. B 83, 180417(R) (2011).

Vopson, M. M., Zemaityte, E., Spreitzer, M. & Namvar, E. Multiferroic composites for magnetic data storage beyond the super-paramagnetic limit. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 113910 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Probing magnetostructural correlations in multiferroic \(\text{ HoAl}_3\)(\(\text{ BO}_3)_4\). Phys. Rev. B 92, 104108 (2015).

Xu, S. et al. Magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroics probed by optical second harmonic generation. Nat. Commun. 14, 2274 (2023).

Wang, H. & Xiaofeng, Q. Giant optical second harmonic generation in two-dimensional multiferroics. Nano Lett. 17, 5027–5034 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank G.A. Zvyagina for helpful discussions and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors have equally contributed to this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zvyagin, A.A., Slavin, V.V. Governing of the piezoelectric effect by external fields and strains. Sci Rep 14, 18335 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69307-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69307-5