Abstract

Accurately predicting the Modulus of Resilience (MR) of subgrade soils, which exhibit non-linear stress–strain behaviors, is crucial for effective soil assessment. Traditional laboratory techniques for determining MR are often costly and time-consuming. This study explores the efficacy of Genetic Programming (GEP), Multi-Expression Programming (MEP), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) in forecasting MR using 2813 data records while considering six key parameters. Several Statistical assessments were utilized to evaluate model accuracy. The results indicate that the GEP model consistently outperforms MEP and ANN models, demonstrating the lowest error metrics and highest correlation indices (R2). During training, the GEP model achieved an R2 value of 0.996, surpassing the MEP (R2 = 0.97) and ANN (R2 = 0.95) models. Sensitivity and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis were also performed to gain insights into input parameter significance. Sensitivity analysis revealed that confining stress (21.6%) and dry density (26.89%) are the most influential parameters in predicting MR. SHAP analysis corroborated these findings, highlighting the critical impact of these parameters on model predictions. This study underscores the reliability of GEP as a robust tool for precise MR prediction in subgrade soil applications, providing valuable insights into model performance and parameter significance across various machine-learning (ML) approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pavement design is the process of developing plans, materials, and construction techniques to create economical and durable structures capable of withstanding the travelling load for a given period1,2,3. Elements of a flexible pavement system are as follows: surface, base, sub-base and subgrade are the common levels of flexible pavement4,5,6. These layers support the pavement structure and take the static and repeated loads originating from automobiles. Engineers properly choose the materials and provide the correct thickness of the layers of the pavement system to manage and sustain these loads throughout the useful life of the pavement, accommodating functions like traffic loads, types of vehicles, and environmental factors. All pavements have a base that contains a subgrade composed of one or more types of soils. The distribution of loads across various layers leads to deformation, compression, and distortion of subgrade soils 7. During the initial phase of vehicle traffic loading, the subgrade soil structure undergoes a shift in strain, measured in terms of deviator stress (δd). There is a progressive reduction in plastic strain, with the rate of increase in plastic strain declining and almost stagnating with successive stress cycles. Recoverable axial strain represents the resilient modulus (MR), or the elastic modulus under repeated loading processes, which can be determined from the applied deviator stress and recoverable axial strain8,9,10.

The MR is defined as the ratio of the recoverable resilient (elastic) strain (∈ r) to the maximal cyclic stress (σcyc) under repeated dynamic loading:

In pavement engineering, MR is a critical metric for characterizing the elastic characteristics of different types of soil. For structural analysis and pavement design, the resilient modulus of subgrade soils is essential, as it is taken into account by both the AASHTO pavement design technique11 and the Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design Guide (MEPDG)12. Studies have demonstrated that MR significantly affects the design, especially concerning the base course and asphalt layer thickness13. There are two main approaches to determine the MR of subgrade soils: from in situ test equipment and rapid load testing (RLT) and subsequent re-analysis of consolidated- undrained triaxle tests performed on specimens taken from the site. To mimic field conditions, the RLT test imposes varying loads of confining and deviator stresses on either remoulded or undisturbed specimen samples14,15,16. This approach is reliable and provides accurate results in specimen identification, but it is time-consuming and demands the use of skilled and experienced workers and enhanced laboratory instruments. As a result, many state agencies have been reluctant to venture into the use of RLT testing and adopted some other methods17,18,19. In recent decades, in situ test devices have been proposed and have been employed as such as herein below. However, this method calls for accurate relationships between the measurements of field tests and that of laboratory tests initially, and this is still in its infancy13.

Recent advances in machine learning have introduced new methodologies for predicting MR20,21,22,23,24. Machine learning techniques can recognize complex correlations, patterns, and trends in data, offering improved interpretability, more precise predictions, and a deeper understanding of underlying events25,26,27. These capabilities make machine learning a promising method for capturing the complex interactions found in MR. Despite this potential, ML approaches are not widely applied for forecasting MR values in pavement subgrade soils28,29,30. For example, a neuro-fuzzy adaptive interface system (ANFIS) was utilized by Sadrossadat et al.31 in order to accurately estimate MR values in subgrade soils for flexible pavements. Kim et al.32 developed an advanced ANN model to estimate the MR of subgrade soils by incorporating essential physical soil characteristics and stress conditions as input features. Sarkhani Benemaran et al.33 and He et al.34 used ensemble methods for anticipation MR. However, these methods are considered as "black box" design, which can limit its accuracy and transparency35. To overcome these limitations, techniques such as (GEP) and Multi-Expression Programming (MEP) are used36,37,38.

The GEP extension of GP employs fixed-length segments for encoding compact programs39,40,41,42. GEP offers practical usability in addition to precise empirical equations. GEP's use of symbolic concepts to simplify physical processes has earned it the moniker "grey box model"43,44,45,46. Consequently, GEP-based models are believed to perform better than ANN models based on neural networks47. In order to forecast the compressive strength (CS) and tensile strength (TS) of concrete containing silica fume, Nafees et al.48 used MLPNN, GEP, and ANFIS models. CS and TS used databases with 283 and 145 data points, respectively. The outcomes showed that all three models demonstrated a high degree of prediction accuracy. But when it came to generating much higher R2 values than the other approaches, GEP models proved to be superior. GEP has several shortcomings, including complicated and lengthy expressions, high computing needs, laborious hyperparameters tuning, overfitting issues, restricted scalability, and no guarantee of optimality, even if it excels at solving complex, nonlinear problems. However, an innovative approach known as MEP has been created to get around these restrictions. Compared to other evolutionary algorithms, MEP is a more advanced iteration of GP that can produce correct results even in cases when the target's complexity is unknown49. One distinctive characteristic of MEP is its ability to encode several equations (or chromosomes) in a single program. The final representation of the problem is chosen from the best-performing chromosome50. Despite its obvious advantages over other evolutionary algorithms, MEP is still comparatively underutilized in civil engineering. Even in the presence of intricate interactions, MEP exhibits promise in capturing nonlinearities and providing trustworthy forecasts. Alavi et al.51, for example, used MEP to identify the type of soil by considering variables such as soil colour, plastic limit, and liquid limit between sand, fine-grained, and gravel particles. Furthermore, in a number of investigations52, MEP has been used to forecast the elastic modulus of both normal- and high-strength concrete53,54,55,56.

During the evaluation and modelling stages, literature databases are often utilized by both MEP and GEP approaches. In the field of sustainable concrete, where linear GP techniques like MEP and GEP have proven to be more effective in predicting different concrete qualities, their application has grown dramatically57,58,59. The advantages of merging MEP with linear genetic programming (LGP) over alternative neural network-based techniques were emphasized by Grosan and Abraham60. Notably, compared to MEP, the working mechanism of GEP is more complex and advanced. MEP and GEP differ in several key aspects. MEP offers greater flexibility in depicting solutions due to its less dense encoding50. This method allows for code reuse, leading to concise and efficient solution representations. Additionally, MEP allows non-coding sections to be located anywhere on the chromosomes, which enhances the flexibility in encoding genetic information61,62,63. Additionally, by explicitly encoding references to function arguments, MEP improves the transparency and interpretability of models. By utilizing the conventional GEP chromosomal architecture, MEP is able to encode software applications with syntactically sound structures since it has distinct head and tail segments with accurate symbols64. Because of these unique qualities, MEP is a reliable and adaptable approach for precisely modelling and resolving complicated issues in a range of settings. Considering the advantages of both GEP and MEP it is important to compare the outcomes of both techniques and propose the most appropriate one.

Although various applications of GEP exist in geotechnical engineering, GEP and MEP have not been used to predict the MR of subgrade soils. This study aims to utilize GEP and MEP for MR prediction and compare them with ANN. Additionally, various statistical measures were employed to validate the models. Sensitivity and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis were performed to evaluate the effect of inputs on MR. The models' outcomes were also compared with literature to ensure robustness and accuracy. A comparative analysis was performed to provide insight into the effectiveness and accuracy of these techniques, enhancing the understanding and forecasting of MR in pavement subgrade soils. This innovative approach represents a significant advancement in pavement design, offering more accurate and reliable methods for predicting the resilient modulus of subgrade soils.

Data collection

A database containing 2813 data values from twelve compacted subgrade soils (classified as CL, CH, and CL-ML (USCS) or A-4, A-6, and A-7-6 (AASHTO)) was collected for this study. The information was gathered from earlier investigations by scientists, including Rahman et al.65, Ding et al.66, Ren et al.67, Zou et al.68, and Solanki et al.69. Important factors taken into account for MR prediction were moisture content (MC in %), confinement stress (δc in kPa), deviator stress (δd in kPa), number of freeze–thaw cycles (NFT), dry density (γd in kN/m3), and weighted plasticity index (wPI). These factors were selected after a careful analysis of the literature and suggestions from authorities in the field 70,71,72,73.

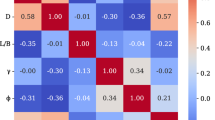

Initially, the links between MR and the previously identified major input variables (γd, wPI, δd, δc, NFT, and MC) are examined in this section. Confinement stress (δc) and deviator stress (δd) affect MR through their influence on soil compaction, shear strength, and deformation behavior. The number of freeze–thaw cycles (NFT) reflects seasonal durability challenges in pavements, impacting soil resilience and potential damage mechanisms. Dry density (γd) governs soil compactness and load-bearing capacity, crucial for pavement stability and deformation resistance. Lastly, the weighted plasticity index (wPI) contributes to soil compressibility and its role in predicting pavement performance. With a correlation coefficient of − 0.35, MC has the highest association with MR of all these variables. The correlation coefficients between MR and the other variables can be seen as: wPI = − 0.025, γd = − 0.27, δd = − 0.114, δc = − 0.033, and NFT = − 0.324 as shown in Table 1.

Tables 2 and 3 provide detailed statistical summaries of the input parameters for training and testing sets, highlighting their distribution characteristics. Skewness and kurtosis measurements were employed to assess the symmetry and distribution patterns relative to a normal distribution. Skewness indicates the degree of asymmetry in the data distribution, while kurtosis measures its tailedness. For robust predictive models, the data distribution's adherence to suggested ranges (skewness close to 0, kurtosis between − 10 and + 10) is crucial, ensuring reliable statistical analysis74. The data points in this study are suitably dispersed throughout the whole range, confirming the robustness of the model, since the input variables for skewness and kurtosis fall within the advised limits. To visualize the relationships between input variables and MR, contour maps (as shown in Fig. 1) and frequency distribution plots (as shown in Fig. 2) were utilized. These tools depict data density and the range of data distribution, confirming the randomness and dispersion of data points across the entire spectrum. Such analyses are essential in machine learning (ML) applications to validate data integrity and model reliability. The thorough examination of these input parameters confirms the reliability and importance of selected parameters in predicting MR.

Methodology

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies employed in GEP and MEP for predicting the MR of compacted subgrade soil. MEP models were developed using the MEPx program, leveraging its specialized capabilities in genetic programming. On the other hand, GEP models were constructed utilizing the Genexpro tool, renowned for its robust features in evolutionary computation (Supplementary information)75. These tools enable precise modeling and prediction of material properties through advanced genetic programming techniques tailored specifically for the challenges posed by subgrade soil analysis75.

Artificial neural networks (ANN)

Most widely used computational techniques called artificial neural networks (ANNs) are modelled after the information processing techniques found in the human brain76,77,78. Instead of using explicit programming, they acquire knowledge by recognizing patterns and correlations in data through experience. An ANN is made up of many processing elements (PE), or artificial neurons, coupled by coefficients (weights). The neural structure is made up of layers of these neurons. A transfer function, a single output, and weighted inputs are present in every processing element (PE). The learning rule, the general design, and the transfer functions of the neurons in the neural network all affect how the network behaves79,80,81. The neural network is a parameterized system because of the weights, the changeable parameters. The activation of the neuron is formed by the weighted sum of its inputs, and its output is obtained by passing it through the transfer function. The network gains non-linearity from the transfer function, which improves its capacity to represent intricate patterns. In order to minimize prediction errors and reach a predetermined accuracy level, a neural network's inter-unit connections are optimized during training. Following testing and training, the network is able to forecast outputs from fresh input data. There are many different kinds of neural networks, and new ones are always being created. The transfer functions of neurons, the learning rule they adhere to, and their connection formulae are characteristics all neural networks share, despite their variations82. ANNs first presented by McCulloch et al.83, are employed to classify and predict non-linear regression problems with high efficiency. Layers of neurons, which are fundamental processing units, make up neural networks. Every neuron in one layer is linked to every other layer's neuron. As seen in Fig. 3a, the computational structure is organized hierarchically and is composed of at least three layers: the input layer (input neurons), one or more computational layers (hidden layers), and the output layer. The variables that are used to train and assess the model are sent out to the input layer. The input and output layers are connected by the computational (hidden) layers, which process the data before delivering it to the output layer, which produces the results of the model84. The literature has extensive documentation of a number of widely used AFs that improve the effectiveness of ANN models85. ANNs often use logistic sigmoid, linear, and hyperbolic tangent sigmoid functions as activation functions86. The linear transfer function (PURELIN) and the BPNN transfer function (TRANSIG) were used in this investigation. During the training phase, these functions improve statistical performance and increase the number of neurons; but, during the testing and validation stages, they impair performance accuracy87. When data propagates from the input neurons into the network, an ANN is trained. To minimize output error, weights are modified according to specified criteria. Using a different dataset set aside for testing, the model is assessed and validated following training.

Genetic expression programming (GEP)

Genetic algorithms (GA) employ strings of fixed length. Koza proposed an alternate approach called genetic programming (GP) in addition to extending GA88,89,90. GP has an effective machine-learning technique thanks to the addition of a spatial parser structure. Nonetheless, only tree crossover is really employed of the three genetic operators found in GP, which results in a massive population of parse trees36. In order to decide which program to end and eliminate underperforming trees, GEP employs a selection mechanism during reproduction91. The GEP algorithm includes a mutation mechanism that is specifically designed to avoid premature convergence and preserve a wide range of genetic variations. The termination criteria in GEP include components such as the terminating set, fitness metrics, outcome identification mechanism, run control parameters, and basic functions. This strategy improves the selection process by eliminating programmes with the lowest fitness during reproduction92 During execution, the trees that are least suitable are removed, and the surviving trees repopulate the population using the selection technique. This evolutionary process ensures the model's initial convergence, guaranteeing continuous progress toward superior solutions92. There are five key components to the GP approach that are necessary for both modelling and research applications. First, fitness evaluation serves as the foundation for evaluating prospective solutions' performance in relation to predetermined standards. By ensuring that only the best ideas advance, this method improves the model's accuracy and efficacy in resolving challenging issues in a variety of fields.

Second, the essential elements that control the modifications and alterations made to the genetic material during the evolutionary process are known as basic domain functions. The diversity and complexity of solutions produced by the GP algorithm are influenced by these functions, which specify how genetic programs change and adapt over the course of multiple generations. These, along with fitness evaluation, constitute the fundamental principles that propel the optimization process and enable GP to successfully address problems in a variety of research contexts, from modelling and classification to optimization and prediction93. Extensive parse trees are produced by a crossover genetic processor, whereas GP builds models automatically. Complex expressions are needed to create non-linear generalized phenotypes 54 to serve the twin roles of genotype and phenotype. This combination makes sure that complicated relationships in the data may be explored and represented by the GP model. The GP algorithm's disregard for neutral genomes is one of its drawbacks. It is difficult to develop widely recognized and simple empirical equations for GP because both the genotype and the phenotype demand a non-linear structure. To address and lessen these inconsistencies, Ferreira developed a new form of GP called the GEP technique52,94,95. The fixed-length linear chromosomes of GA and the parse trees of GP are combined to form GEP. One notable modification to GEP is that, since modifications happen in a simple linear fashion, only the genome is handed on to the following generation, negating the need to reproduce the complete structure. The development of a model with a single chromosome made up of many genes divided into head and tail parts is another noteworthy characteristic96,97,98. In a GEP model, every gene has mathematical operators, a terminating function, and a fixed parametric length. The genetic code operator in GEP has a stable connection between the terminals and the chromosomes. The chromosomes contain the data needed to build the GEP model, and a novel language known as "karva" has been created to understand this information. Phenotypes can be predicted from genetic sequences using the GEP technique, which entails tracing nodes from the root to the deepest layer in order to translate expression trees (ETs) into Karva expressions (K-expression). The various ETs employed in GEP have an impact on this conversion process and may contain duplicated sequences that are not necessary for genome mapping99. This could lead to length disparities between K-expression and GEP genes. In order to assess each person's fitness, fixed-length chromosomes, or ETs, are randomly created at the beginning of the GEP process. The process involves numerous generations of selection and reproduction among potential people in an iterative cycle of reproduction and selection that continues until optimal solutions are reached as shown in Fig. 3b. To hasten the population's evolution, genetic processes including crossover, mutation, and reproduction are used.

Multi expression programming (MEP)

Phenotypes can be predicted from genetic sequences using the GEP technique, which entails tracing nodes from the root to the deepest layer in order to translate expression trees (ETs) into Karva expressions (K-expression). The various ETs employed in GEP have an impact on this conversion process and may contain duplicated sequences that are not necessary for genome mapping99. In order to assess each person's fitness, fixed-length chromosomes, or ETs, are randomly created at the beginning of the GEP process. The process involves numerous generations of selection and reproduction among potential people in an iterative cycle of reproduction and selection that continues until optimal solutions are reached. There are various ways that MEP and GEP vary. Because it is less densely encoded, solutions can be represented with greater flexibility100. Compact and effective solution representations are made possible by MEP's code reuse feature. Non-coding sections in MEP can also exist at any location along the chromosomes, providing further flexibility in the encoding of genetic information. MEP encodes references to function arguments clearly, improving model interpretability and transparency. It follows the traditional GEP chromosomal structure, with unique head and tail segments with accurate symbols that efficiently encode software programs with structures that make sense syntactically. These unique qualities establish MEP as a potent and adaptable technique for precise modelling and resolving difficult problems in a variety of fields. Similar to its GEP counterpart, the MEP model allows for the optimization of its performance by permitting alterations to a number of important factors, providing a high degree of flexibility101. These characteristics, which influence how well MEP performs in various applications, include the function set, crossover probability, subpopulation size, and code length. For example, MEP's capacity to manage computational efficiency and assessment complexity is highly influenced by the size and variety of its subpopulations, particularly when working with big datasets and varied programmed structures. Moreover, the MEP model's performance on a variety of tasks is similarly influenced by the algorithmic code length and the probability of crossover events101. The interpretability and computational demand of the model are directly impacted by the code length, which also has an impact on the length and complexity of the mathematical expressions produced by MEP. The architecture of MEP is shown in Fig. 3c.

Model structures

The key to creating a strong artificial intelligence prediction model is to pick the most important input variables with attention. During this process, every input parameter that was present in the database was thoroughly analyzed. Through early runs and statistical studies, the possible impact of each variable on the MR of subgrade soil was carefully assessed. Consideration was denied to variables that showed little effect on MR and to characteristics that were infrequently covered in pertinent literature. Only the most important variables made it into the final predictive model thanks to this strict selection procedure. This procedure culminates in Eq. (2), which is the revised model for predicting the compressive strength of concrete. Based on the chosen input variables that had strong correlations with MR in the early analysis, this equation was created. The model leverages insights from both theoretical considerations and practical facts to produce reliable MR predictions by concentrating on these critical elements. In the realm of geotechnical engineering, this method not only increases the predicted accuracy of the model but also guarantees its relevance and applicability in actual situations.

Appropriate hyper parameter selection and optimization are crucial to building scalable and reliable GEP, ANN and MEP models. To determine the best combinations, these factors are adjusted iteratively by referring to previous research publications51. The population size is one of these factors that is very important in controlling how the programs in the model evolve. More accurate and complex models are frequently produced with larger populations. But if the population grows, so too could the computing load and time needed to find the optimal answer. Therefore, when estimating the population size, it is crucial to strike a balance between the trade-off between model complexity and available computational resources. Furthermore, overfitting a condition in which the model performs badly on fresh data and becomes extremely specialized to the training set can result from beyond a particular threshold for population size. As a whole, the reliability and scalability of the GEP, ANN and MEP models are strongly influenced by the careful selection of hyper parameters, such as population size. Through careful trial-and-error optimization of these hyper parameters and the application of prior research, a more reliable and efficient modelling framework can be created. This method guarantees that the models are efficient, accurate, and have good data generalization abilities.

GEP model

Genexpro Tools software was used to create the GEP model, which predicts the MR of subgrade soil. Genetic operator selection has a major impact on how well genetic-based modelling works. For instance, the crossover rate plays a significant role in the convergence of GEP and MEP models; larger crossover rates are frequently associated with earlier convergence and lower diversity. On the other hand, mutation rates impact exploration; too high a mutation rate may cause important data to be disrupted. The size and organization of a program are greatly influenced by the transposition operator. Model performance can be improved by extending the head, code length, and linking functions, but doing so may also make the model more complex and less efficient. Furthermore, the accuracy of the GEP and MEP models is strongly affected by modifications to other genetic operators. Previous research102 served as a guide for the initial parameter selection in this work, which aimed to determine the ideal GEP model setup. The number of chromosomes within a population is determined by its size, which is a crucial element impacting the model's performance. In addition, the quantity of genes and the size of the head section are two important factors that characterize the structure of the GEP model. In this model, the head section size is set to 10, which affects the intricacy of each generated expression, and so determines the complexity of the model. The complexity of the GEP model results from summing expression trees, or sub-ETs. For maximum performance, key parameters, including head size, population size, and gene count, need to be carefully regulated. The structure and functioning of the model are improved by four extra genes. Table 4 provides a summary of the carefully chosen hyperparameters that guarantee precision and dependability. Gene numbers and head sizes rose when connections were made using a multiplication function. The process was repeated several times in order to improve the model.

MEP model

In order to construct compact equations utilizing basic mathematical operations such as division, addition, multiplication, and subtraction, the MEP model was first deployed with ten subpopulations. In order to maximize accuracy, different crossover probability configurations between 50 and 90% were evaluated during the model's development103. These modifications were essential for perfecting the MEP models, which were created with the MEPx program, a specialized application made for Multi-Expression Programming (MEP) uses. Starting with a count of 10 and a subpopulation size of 260, the MEP modelling procedure was initiated. The hyperparameters utilized are listed in Table 4. To arrive at a straightforward final equation, basic arithmetic operations (division, subtraction, addition, and multiplication) were used. Setting a limit on the number of generations made it possible to make iterative improvements until the required level of precision. Creating a generation-based termination criterion and making strategic hyperparameter decisions were essential to creating a strong MEP model. More generations resulted in fewer errors and increased accuracy. By varying the crossover chance and mutation rate, the likelihood of children undergoing genetic operations like crossover and mutation was regulated. The ideal set of values was found via rigorous testing with several hyperparameter combinations (explained in Table 5). To ensure the model's accuracy and dependability, the evaluation period for every generation was thoughtfully chosen. In this investigation, a halting criterion was created, even though the model can evolve endlessly with additional variables. To be more precise, the model stops evolving when the fitness function changes by less than 0.1% or after 1000 generations. These standards function as performance indicators, showing at what point further evolution ceases to yield appreciable improvements to the model. They make it possible to effectively control the model's performance, guaranteeing the right level of efficiency and accuracy.

ANN model

ANN models were created by applying the Levenberg–Marquardt technique. Ten hidden neurons were used, and the data were divided up randomly. For the iteration procedure, a feed-forward back-propagation network type was utilized. To find the ideal number of hidden layers for attaining the required performance, the trial-and-error approach was modified in this study. The parameters for the ANN method modelling process in this study are shown in Table 6. Forward propagation is used in this study, in which each previous neuron processes and sends information to the neurons that come after it. Weights (γd, wPI, δd, δc, NFT, and MC) that indicate the importance of the input data in relation to the output have an impact on each input. Every node also adds a threshold value (n) to the total of the weighted signal inputs. After that, the integrated input (Kn) is converted from one unit of measurement to another using a non-linear activation function (AF). In ANNs, the AFs are essential because they add non-linearity, which greatly affects the model's efficacy. Choosing the right AF is, therefore, essential.

Model’s performance evaluation

The coefficient of correlation, denoted as R, is a common metric used to evaluate a model's efficacy and efficiency. However, R has its limitations; it may not accurately reflect a model's performance in handling simple mathematical operations such as scaling outputs by constants, potentially masking underlying issues. To address these limitations, this study incorporates additional error measures into the evaluation system. These measures include mean absolute error (MAE), relative root mean square error (RRMSE), relative square error (RSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). Using these measures alongside R provides a more comprehensive evaluation of the model's accuracy and predictive power. The inclusion of RSE, RMSE, MAE, and RRMSE enables a detailed examination of the model's performance across various scenarios. RSE provides insights into overall prediction accuracy by calculating the relative difference between actual and projected values. RMSE and MAE measure the average size of errors, with RMSE placing more emphasis on larger errors due to its squared form. RRMSE offers a relative measure of prediction accuracy by normalizing RMSE against the mean of observed values, complementing the information provided by RMSE. Collectively, these measures present a clearer picture of the model's fit to real data and its generalizability across different datasets and conditions. To further enhance the evaluation of model performance, additional indices such as the A10-index, variance account for (VAF)104, scatter index (SI)35, and index of agreement (IA)33 are used. These indices offer diverse perspectives on model accuracy and reliability, contributing to a more robust assessment framework. The study also introduces a performance index, represented by ρ105, which combines the RRMSE and R functions. This index provides a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance by integrating the strengths of both R and RRMSE. In order to ensure the model's generalizability, the data was split into training and testing phases, with 70% of the data used for training and 30% for testing. This approach helps validate the model's performance on unseen data, providing a realistic assessment of its predictive capabilities. By employing this multi-faceted evaluation strategy, the model's performance is assessed more accurately, allowing researchers to interpret its results more reliably in practical applications. This comprehensive approach addresses potential shortcomings that traditional metrics might overlook, ensuring a more thorough assessment of the model's predictive skills. The recommended equations for each of the metric are presented in Table 7.

The aforementioned equations use the following notations: "\({m}_{c}\)" stands for the cth experimental output, "\({g}_{c}\)" for the model anticipated output, "\({\overline{m}}_{c}\)" for the average of the experimental/actual outputs, "\({\overline{g}}_{c}\)" for the mean value of the model outputs, and "w" for the total number of samples calculated. Based on their respective average values, these formulas provide a useful tool for evaluating the relative inaccuracy or disagreement between actual and model estimations. For a model to be considered reliable and well-calibrated, it must have a high R value, which denotes a strong correlation between forecast and actual values; low RMSE, RRMSE, and MSE values also indicate that the model is capable of accurately capturing underlying data patterns and guaranteeing close alignment with real experimental data. Researchers should focus on achieving high R values and minimizing error metrics because these indicators together validate the model's accuracy and its fidelity in reflecting real-world data. When a model is over-trained on data in machine learning, it is called overfitting and causes testing mistakes to rise quickly while training errors continue to decline106. Equation (16) denotes the objective function (OBF) that is proposed by Gandomi and Roke107 to address this problem. By acting as the fitness function and directing the choice of the ideal model configuration, this OBF counteracts the overfitting effect. This strategy effectively addresses the overfitting issue by balancing generalizability and complexity, ensuring the model remains reliable and accurate in forecasting new data. The strong correlation between measured and predicted values, commonly shown by an R-value higher than 0.8 (or even 1 for a perfect fit), has been suggested as an indicator of the model's efficacy. Better model performance is indicated by a lower RRMSE number, which falls between 0 and positive infinity. This multi-metric method guarantees a thorough assessment of the correctness and dependability of the model.

The subscripts "f" and "s" in the equation designate training and validation (or testing) data, respectively, while "w" denotes the total number of data points. In order to appropriately evaluate overall model performance, the objective function (OBF) takes into account characteristics such as R and RRMSE in addition to the relative distribution of dataset entries throughout these sets. Reducing the OBF is essential because, as its value gets closer to zero, it indicates a precise and well-calibrated model. By running simulations with over 20 different combinations of the fitting parameters, the study determined which model had the lowest bias factor. This method efficiently chooses the model that performs at its best out of all the parameter combinations that are investigated.

Results and discussion

GEP model formulation

Figure 4 presents expression trees (ETs) generated by GeneXproTool, a software tool used to extract empirical expressions for predicting the resilient modulus (MR) of subgrade soil. These ETs are decoded to derive an empirical expression based on basic arithmetic operations: addition ( +), subtraction (-), multiplication ( ×), and division ( ÷). Equations (17–21) simplify the derived expressions. This straightforward expression facilitates efficient and user-friendly MR prediction for subgrade soil, highlighting its practical utility in modeling and analysis.

MEP model formulation

An empirical equation was developed to estimate the resilient modulus (MR) of subgrade soil using the MEPx software. The MEP analysis considered six important independent variables, which were vital to the investigation. These variables were selected based on their significant impact on the MR, ensuring that the final equation accurately reflects the complex interactions affecting soil resilience. Thus, the derived equation, as seen in Eq. (22), is a reliable mathematical expression designed to predict MR values. This equation, developed through MEP, is straightforward to use in practice and is particularly valuable in geotechnical applications where precise forecasts of soil behaviour are crucial.

Accuracy evaluation of GEP model

The scatter plots of the proposed GEP equation for both the training and validation stages are provided in Fig. 5. The analysis reveals that the GEP model demonstrates impressive performance metrics. As shown in Fig. 5, the model achieved an R-value of 0.996 during the training phase, indicating a very high correlation between predicted and actual values. Similarly, during the testing phase, the model maintained an R-value of 0.99, further demonstrating its strong predictive capability. Figure 6a and b illustrate the relationship between the absolute error of the GEP equation and the corresponding experimental values. The maximum, minimum, and average errors in the GEP model are also identified, as shown in Fig. 11a and b, providing additional insights into its performance characteristics. The maximum error during the GEP training phase was 12.045 MPa, with an average error of 1.715 MPa. During the testing stage, the average error was 2.570 MPa, and the maximum error was 14.445 MPa. The consistency of these error values between the training and testing phases underscores the precision and versatility of the proposed GEP expression. This consistency indicates the model's effectiveness in predicting outcomes for new and unobserved data while minimizing the risk of overfitting.

Accuracy evaluation of MEP model

The scatter plots for the MEP model are presented in Fig. 7. In the figure, it can be observed that the experimental and predicted values are very close, with slope values of 0.94 and 0.96 in the training and testing stages. The MEP model achieved an R value of 0.97, demonstrating a strong correlation between the predicted and experimental values. Furthermore, error analysis was performed, with the overall error in the models shown in scatter and 3D plots in Fig. 8a and b. The additional radar plots are also plotted, as shown in Fig. 11a and b for training and testing sets separately. the maximum, mean, and average error was noted as 18 MPa and 19 MPa, 3 MPa, and 2 MPa, and 5 MPa and 4 MPa, respectively, in both sets. These results indicate that the MEP model has a high degree of accuracy and reliability in predicting outcomes, with errors consistently low and a strong alignment between predicted and actual values. The performance of the MEP model, as illustrated by the low error values and high correlation, underscores its effectiveness in predicting the mechanical characteristics of subgrade soil.

Accuracy evaluation of ANN model

A thorough statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate the ANN model's capability. The scatter plots for the ANN model are presented in Fig. 9. It is suggested that slope values should be close to 1. In the figure, it can be observed that the experimental and predicted values are very close, with slope values of 0.95 and 0.94 in the training and testing stages. In the training phase, the ANN model's R-value was 0.967, while in the testing phase, it was assessed at 0.953. Furthermore, the overall error in the model is shown in scatter and 3D plots in Fig. 10a and b. In addition, the radar plots are also used, as shown in Fig. 11a and b, to visualize the range and average error in both the training and testing stages. The error analysis revealed that, in the training phase, the model's errors ranged from a minimum of 0.002 MPa to a maximum of 26.00 MPa. During the testing phase, the error ranged from a minimum of 0.008 MPa to a maximum of 30.710 MPa. The average error was measured as 4 MPa and 3 MPa, respectively. While the ANN demonstrated the ability to produce highly accurate predictions under certain conditions, it was noted that the ANN was outperformed by both the MEP and GEP models, as their recorded errors were lower than those of the ANN model.

External verification of GEP and MEP and ANN models

The GEP and MEP, and ANN models were also evaluated by external validation in order to assess their performance using standards recommended by earlier studies. Table 8 provides a brief summary of these external verification checks' outcomes. The gradient of the regression lines that pass through the origin is represented by the value indicated by (\({k}{\prime}\) of \(k\)); these values should ideally approach 1. The accuracy of all the proposed equations has proven to be impressive, effectively satisfying the given criteria. Although there is no statistical error and a greater correlation coefficient in the GEP equation, both models have strong predictive powers. Its deployment in practical applications is further facilitated by its compact character. Evaluation of \({{R{\prime}}_{o}}^{2}\) and \({{R}_{o}}^{2}\), which stand for the coefficient of determination between the results of the proposed model and the experimental data and the results of the proposed model and the experimental data, respectively was advised by another study. These numbers should ideally get closer to 1. All of the three proposed models, as indicated in Table 6, satisfy this condition, demonstrating their dependability and precision in predicting the MR of subgrade soil.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is a methodical way to find out how changes in a model or system's input, or independent factors, affect its output or dependent variables. This analysis's primary objective is to evaluate a model or system's sensitivity or responsiveness to changes in its input parameters. These input variables have a major impact on the model's anticipated results. The quantity of input variables and data points utilized to build the model has an impact on the results of sensitivity tests. The machine learning method used is able to evaluate each parameter's contribution separately. It's crucial to remember that changes in the proportions of the components and the addition of additional input variables could cause these evaluations to become inconsistent. The relative importance of each input parameter in predicting the MR of subgrade soil is revealed by Eqs. (23) and (24). In addition to highlighting the significance of each variable, this analysis provides insightful direction for further study and real-world applications in the field of geotechnical engineering.

The previously discussed equations provide the upper and lower boundaries of the projected output, represented as h max (\({p}_{b}\)) and h min (\({p}_{b}\)) respectively, based on the b-th input domain. These findings demonstrate how some parameters, namely, dry density (26.89%), confining stress (21.6%), moisture content (14.6%), weighted plasticity index (14.92%), deviator stress (13.2%), and freeze–thaw cycles (10.3%) have a large, proportionate impact on the outcome projection. The influence of each input component on MR prediction is graphically represented in Fig. 12, which shows how these factors contribute across the spectrum. The other input variables are kept at their average values for the duration of this investigation. The computed sensitivity percentages for each parameter are presented in a clear and concise manner by the sensitivity analysis, which also offers insightful information about the parameters' relative importance inside the model.

SHAP analysis

As sensitivity analysis only provides information regarding the influence of each variable on output, it is also important to examine the positive or negative impact of each variable on the output. For this purpose, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was also performed in this study. SHAP analysis provides a unified measure of feature importance, allowing for the decomposition of individual predictions to understand the impact of each feature on the model’s output, both positively and negatively108. The summary plots for SHAP outputs are shown in Fig. 13. Additionally, feature plots representing the positive and negative influences are also provided, as shown in Fig. 14. It can be seen that moisture content (MC) has both positive and negative influences on the resilient modulus (MR), represented by red and blue dots, respectively. Similarly, dry density and deviator stress have a higher positive influence, while NFT has a negative influence on MR. These findings align well with the literature, demonstrating the reliability of the models used in this study109. The SHAP analysis thus provides a more nuanced understanding of how each variable affects the output, enhancing the interpretability and robustness of the model's predictions.

Comparative study of ANN, MEP, and GEP model outcomes

The outcomes of the comparative study between the ANN, MEP, and GEP models are shown in Fig. 15 and Table 3, which demonstrate the superior performance of the GEP model during both the training and testing phases. The GEP model consistently exhibited lower error values and higher coefficients of regression (R2) compared to the MEP and ANN odels. During the training phase, the GEP model achieved an RMSE of 2.408 MPa and an R2 value of 0.992, outperforming the MEP model (RMSE: 3.821 MPa, R2: 0.980) and the ANN model (RMSE: 4.937 MPa, R2: 0.966). This indicates that the GEP model's predictions were not only more accurate but also more consistent. Similarly, during the testing phase, the GEP model maintained its superiority with an RMSE of 3.636 MPa and an R2 value of 0.981, compared to the MEP model (RMSE: 4.889 MPa, R2: 0.966) and the ANN model (RMSE: 7.384 MPa, R2: 0.946). In terms of MAE, the GEP model demonstrated lower values (1.715 MPa in training and 2.570 MPa in testing) compared to the MEP (2.499 MPa in training and 3.284 MPa in testing) and ANN models (3.102 MPa in training and 5.481 MPa in testing). Additionally, the GEP model showed higher IA, A10-index, and VAF values and lower values of SI and PI, highlighting its better performance in capturing the variability of the observed data. The complete summary of these measures is presented in Table 9. The rank for the proposed was also calculated, as shown in Fig. 16. The highest rank of 10 was assigned to the model with the best performance, and the lowest numerical rank of 1 was given to models with lower performance. The GEP model consistently achieved the highest ranks during both the training and testing phases, with ranks of 9.200 and 8.000, respectively. In contrast, the ANN model had the lowest rank (6.600 in training and 4.500 in testing). When comparing the models based on the percentage improvement in average errors, the GEP model performed approximately 55% better than the ANN model and 20% better than the MEP model. These percentages reflect the GEP model's enhanced predictive capabilities and robustness.

Additionally, Taylor diagrams (shown in Fig. 17) were also used to provide a visual comparison of model performance by displaying the correlation coefficient and standard deviation of model predictions against observed data for both training and testing sets. It can be seen that the GEP model performed superior with higher correlation compared to the MEP and ANN models.

Comparative analysis in the light of literature

Although there are no computational models using GEP and MEP for forecasting the MR, various other machine-learning techniques have been used in the past, as shown in Table 10. It is evident from the table that the existing models demonstrate comparable or higher accuracy in predicting MR. The high level of comparability between the values of R2 and RMSE of the existing models and the models suggested in this study confirms the efficiency of the developed models. Thus, the proposed MEP and GEP models offer a reliable and accurate method for forecasting the MR of subgrade soil.

Conclusion

Understanding the resilient modulus (MR) is essential for comprehending the stress–strain behavior of subgrade materials, especially regarding their non-linear characteristics. Traditional procedures for determining MR through laboratory testing are frequently complex, time-consuming, expensive, and difficult. This study highlights the efficacy of advanced machine learning techniques, including GEP, MEP, and ANN, in accurately forecasting MR in subgrade soil, potentially enhancing our capacity to predict and understand soil behavior. Key findings from this study can be drawn as follows.

-

The GEP model demonstrated superior performance with training phase metrics of R: 0.996, MAE: 1.715 MPa, RMSE: 2.408 MPa, and testing phase metrics of R: 0.990, MAE: 2.570, RMSE: 3.636 MPa.

-

The ANN model showed good performance with training phase metrics of R: 0.983, MAE: 3.102, RMSE: 4.937 MPa, and testing phase metrics of R: 0.973, MAE: 5.481, RMSE: 7.384 MPa.

-

The MEP model also performed well with training phase metrics of R: 0.990, MAE: 2.499, RMSE: 3.821 MPa, and testing phase metrics of R: 0.983, MAE: 3.284, RMSE: 4.889 MPa.

-

The GEP model outperformed the MEP and ANN models with lower statistical errors (RMSE, MAE, SI, and PI) and higher correlation indices (VAF and R2).

-

GEP exhibited approximately 55% better performance than ANN and 20% better than MEP based on average errors.

-

Sensitivity SHAP analysis showed comparative results with the literature and identified dry density (26.89%), confining stress (21.6%), and moisture content (14.6%) as the most influential parameters.

-

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that advanced machine learning models, especially GEP, offer significant potential for accurately predicting the resilient modulus of subgrade soils. These findings underscore the practical value and feasibility of employing machine learning techniques in geotechnical engineering, paving the way for more efficient and cost-effective soil behaviour analysis.

Future research directions

Although the findings from the GEP, ANN, and MEP models are promising, it is crucial to compare their effectiveness against other advanced machine learning methods. Future research could explore the integration of these models with hybrid approaches or deep learning techniques to further enhance prediction accuracy. Additionally, expanding the dataset to include a broader range of soil types and conditions could provide a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance.

Data availability

All data used in this study is available in the manuscript.

References

Hayat, A., Hussain, A. & Afridi, H. F. Determination of in-field temperature variations in fresh HMA and corresponding compaction temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 216, 84–92 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. In-time density monitoring of in-place asphalt layer construction via intelligent compaction technology. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35, 04022386 (2023).

Afridi, H. F. & Khattak, M. J. Self-healing characteristics of polyvinyl alcohol-fiber-reinforced hot mix asphalt for enhanced pavement durability. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981241231969 (2024).

Yoder, E. J. & Witczak, M. W. Principles of pavement design. Princ. Pavement Des https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470172919 (1975).

Thompson, M. R. & Robnett, Q. L. Resilient properties of subgrade soils. ASCE Transp. Eng. J. 105, 71–89 (1979).

Huang, H., Huang, M., Zhang, W., Pospisil, S. & Wu, T. Experimental investigation on rehabilitation of corroded RC columns with BSP and HPFL under combined loadings. J. Struct. Eng. 146, 04020157 (2020).

Huang, H. et al. Numerical investigation on the bearing capacity of RC columns strengthened by HPFL-BSP under combined loadings. J. Build. Eng. 39, 102266 (2021).

Mazari, M., Navarro, E., Abdallah, I. & Nazarian, S. Comparison of numerical and experimental responses of pavement systems using various resilient modulus models. Soils Found. 54(1), 36–44 (2014).

Alkhattabi, L. & Arif, K. Novel base predictive model of resilient modulus of compacted subgrade soils by using interpretable approaches with graphical user interface. Mater. Today Commun. 40, 109764 (2024).

Jalal, F. E., Xu, Y., Iqbal, M., Jamhiri, B. & Javed, M. F. Predicting the compaction characteristics of expansive soils using two genetic programming-based algorithms. Transp. Geotech. 30, 100608 (2021).

AASHTO 93. AASHTO Guide for design of pavement structures. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Preprint at (1993).

Romanoschi, S. A., Momin, S., Bethu, S. & Bendana, L. Development of traffic inputs for new mechanistic-empirical pavement design guide. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.3141/2256-17 (2011).

Nazzal, M. D. & Mohammad, L. N. Estimation of resilient modulus of subgrade soils for design of pavement structures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 22, 726–734 (2010).

AASHTO. AASHTO: T307–99 Standard Method of Test for Determining the Resilient Modulus of Soils and Aggregate Materials. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Washington D.C., USA 99, (2003).

Huang, H., Yuan, Y., Zhang, W. & Li, M. Seismic behavior of a replaceable artificial controllable plastic hinge for precast concrete beam-column joint. Eng. Struct. 245, 112848 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Zhang, C. Using viscoelastic materials to mitigate earthquake-induced pounding between adjacent frames with unequal height considering soil-structure interactions. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 172, 107988 (2023).

Zhou, X. et al. A 3D non-orthogonal plastic damage model for concrete. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 360, 112716 (2020).

Zhang, W., Zheng, D., Huang, Y. & Kang, S. Experimental and simulative analysis of flexural performance in UHPC-RC hybrid beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 436, 136889 (2024).

Huang, H., Huang, M., Zhang, W. & Yang, S. Experimental study of predamaged columns strengthened by HPFL and BSP under combined load cases. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 17, 1210–1227 (2021).

Riaz, K. & Ahmad, N. Predicting resilient modulus: A data driven approach integrating physical and numerical techniques. Heliyon 10, e25339 (2024).

Esmaeili-Falak, M., Katebi, H., Vadiati, M. & Adamowski, J. Predicting triaxial compressive strength and young’s modulus of frozen sand using artificial intelligence methods. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 33, 04019007 (2019).

Zhang, C., Duan, C. & Sun, L. Inter-storey isolation versus base isolation using friction pendulum systems. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455424500226 (2024).

Hu, D. et al. Surface settlement prediction of rectangular pipe-jacking tunnel based on the machine-learning algorithm. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 15(1), 04023061 (2024).

Qin, C. et al. RCLSTMNet: A Residual-convolutional-LSTM Neural Network for Forecasting Cutterhead Torque in Shield Machine. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 22, 705–721 (2024).

Huang, H., Xue, C., Zhang, W. & Guo, M. Torsion design of CFRP-CFST columns using a data-driven optimization approach. Eng. Struct. 251, 113479 (2022).

Jalal, F. E. et al. ANN-based swarm intelligence for predicting expansive soil swell pressure and compression strength. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65547-7 (2024).

Farooq, F., Ahmed, W., Akbar, A., Aslam, F. & Alyousef, R. Predictive modeling for sustainable high-performance concrete from industrial wastes: A comparison and optimization of models using ensemble learners. J. Clean Prod. 292, 126032 (2021).

Kardani, N. et al. Prediction of the resilient modulus of compacted subgrade soils using ensemble machine learning methods. Transp. Geotech. 36, 100827 (2022).

Chen, C., Han, D. & Chang, C. C. MPCCT: Multimodal vision-language learning paradigm with context-based compact Transformer. Pattern Recognit. 147, 110084 (2024).

Chen, C., Han, D. & Shen, X. CLVIN: Complete language-vision interaction network for visual question answering. Knowl. Based Syst. 275, 110706 (2023).

Mohammadzadeh: Prediction of compression index of... - Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Prediction of compression index of fine-grained soils using a gene expression programming model&publication_year=2019&author=S. Mohammadzadeh&author=S.-F. Kazemi&author=A. Mosavi&author=E. Nasseralshariati&author=J.H. Tah.

Shishegaran, A., Boushehri, A. N. & Ismail, A. F. Gene expression programming for process parameter optimization during ultrafiltration of surfactant wastewater using hydrophilic polyethersulfone membrane. J. Environ. Manag. 264, 110444 (2020).

SarkhaniBenemaran, R., Esmaeili-Falak, M. & Javadi, A. Predicting resilient modulus of flexible pavement foundation using extreme gradient boosting based optimised models. Int. J. Pavement Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/10298436.2022.2095385 (2023).

He, B. et al. A case study of resilient modulus prediction leveraging an explainable metaheuristic-based XGBoost. Transp. Geotechn. 45, 101216 (2024).

Bian, J., Huo, R., Zhong, Y. & Guo, Z. XGB-northern goshawk optimization: predicting the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 28, 1423–1439 (2024).

Chu, H. H. et al. Sustainable use of fly-ash: Use of gene-expression programming (GEP) and multi-expression programming (MEP) for forecasting the compressive strength geopolymer concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12, 3603–3617 (2021).

Shi, S., Han, D. & Cui, M. A multimodal hybrid parallel network intrusion detection model. Conn. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2023.2227780 (2023).

Wang, H., Han, D., Cui, M. & Chen, C. NAS-YOLOX: A SAR ship detection using neural architecture search and multi-scale attention. Conn. Sci. 35, 1–32 (2023).

Alaskar, A. et al. Comparative study of genetic programming-based algorithms for predicting the compressive strength of concrete at elevated temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e02199 (2023).

Alyami, M. et al. Predictive modeling for compressive strength of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using machine learning algorithms. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e02728 (2024).

Su, Y. et al. End-to-end deep learning model for underground utilities localization using GPR. Autom. Constr. 149, 104776 (2023).

Han, D. et al. LMCA: a lightweight anomaly network traffic detection model integrating adjusted mobilenet and coordinate attention mechanism for IoT. Telecommun. Syst. 84, 549–564 (2023).

Asif, U., Memon, S. A., Javed, M. F., Kim, J. & LuísaVelosa, A. Predictive modeling and experimental validation for assessing the mechanical properties of cementitious composites made with silica fume and ground granulated blast furnace slag. Buildings 14, 1091 (2024).

Dou, J. et al. surface activity, wetting, and aggregation of a perfluoropolyether quaternary ammonium salt surfactant with a hydroxyethyl group. Molecules 28(20), 7151 (2023).

Fei, R., Guo, Y., Li, J., Hu, B. & Yang, L. An improved BPNN method based on probability density for indoor location. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. E 106, 773–785 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Intelligent control of multilegged robot smooth motion: A review. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3304992 (2023).

Iqbal, M. F. et al. Sustainable utilization of foundry waste: Forecasting mechanical properties of foundry sand based concrete using multi-expression programming. Sci. Total Environ. 780, 146524 (2021).

Nafees, A. et al. Predictive modeling of mechanical properties of silica fume-based green concrete using artificial intelligence approaches: MLPNN, ANFIS, and GEP. Materials 14, 7531 (2021).

Asif, U., Javed, M. F., Alyami, M. & Hammad, A. W. Performance evaluation of concrete made with plastic waste using multi-expression programming. Mater. Today Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MTCOMM.2024.108789 (2024).

Ahmed, H. U. et al. Innovative modeling techniques including MEP, ANN and FQ to forecast the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete modified with nanoparticles. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 1–27 (2023).

Alavi, A. H., Gandomi, A. H., Sahab, M. G. & Gandomi, M. Multi expression programming: A new approach to formulation of soil classification. Eng. Comput. 26, 111–118 (2010).

Zhao, Y. et al. Release pattern of light aromatic hydrocarbons during the biomass roasting process. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29061188 (2024).

Khan, M., Cao, M., Chaopeng, X. & Ali, M. Experimental and analytical study of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete prepared with basalt fiber under high temperature. Fire Mater. 46, 205–226 (2022).

Alabduljabbar, H. et al. Predicting ultra-high-performance concrete compressive strength using gene expression programming method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e02074 (2023).

Chen, D. L., Zhao, J. W. & Qin, S. R. SVM strategy and analysis of a three-phase quasi-Z-source inverter with high voltage transmission ratio. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 66, 2996–3010 (2023).

Meng, S., Meng, F., Chi, H., Chen, H. & Pang, A. A robust observer based on the nonlinear descriptor systems application to estimate the state of charge of lithium-ion batteries. J. Franklin Inst. 360, 11397–11413 (2023).

Iqbal, M. F. et al. Prediction of mechanical properties of green concrete incorporating waste foundry sand based on gene expression programming. J. Hazard Mater. 384, 121322 (2020).

Lu, D. et al. A dynamic elastoplastic model of concrete based on a modeling method with environmental factors as constitutive variables. J. Eng. Mech. 149, 04023102 (2023).

Su, F. Q. et al. Estimation of the cavity volume in the gasification zone for underground coal gasification under different oxygen flow conditions. Energy 285, 129309 (2023).

Grosan, C. & Abraham, A. Stock market modeling using genetic programming ensembles. In Genetic systems programming: Theory and experiences 131–146 (Heidelberg, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, 2006).

Li, J., Tang, H., Li, X., Dou, H. & Li, R. LEF-YOLO: A lightweight method for intelligent detection of four extreme wildfires based on the YOLO framework. Int. J. Wildland Fire https://doi.org/10.1071/WF23044 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Study on optimization and combination strategy of multiple daily runoff prediction models coupled with physical mechanism and LSTM. J. Hydrol. (Amst) 624, 129969 (2023).

Xie, X. et al. Fluid inverse volumetric modeling and applications from surface motion. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Gr. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2024.3370551 (2024).

IftikharFaraz, M. et al. A comprehensive GEP and MEP analysis of a cement-based concrete containing metakaolin. Structures 53, 937–948 (2023).

Rahman, T. Evaluation of moisture, suction effects and durability performance of lime stabilized clayey subgrade soils. (2014).

Ding, L. Q., Han, Z., Zou, W. L. & Wang, X. Q. Characterizing hydro-mechanical behaviours of compacted subgrade soils considering effects of freeze-thaw cycles. Transp. Geotech. 24, 100392 (2020).

Ren, Y., Zhang, L. & Suganthan, P. N. Ensemble classification and regression-recent developments, applications and future directions. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 11(1), 41–53 (2016).

Zou, W. L., Han, Z., Ding, L. Q. & Wang, X. Q. Predicting resilient modulus of compacted subgrade soils under influences of freeze–thaw cycles and moisture using gene expression programming and artificial neural network approaches. Transp. Geotech. 28, 100520 (2021).

Solanki, P., Zaman, M. & Khalife, R. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on performance of stabilized subgrade. 566–580 (2013) https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784412770.038.

Ghorbani, B., Arulrajah, A., Narsilio, G., Horpibulsuk, S. & Bo, M. W. Development of genetic-based models for predicting the resilient modulus of cohesive pavement subgrade soils. Soils Found. 60, 398–412 (2020).

Zhang, W. et al. Application of deep learning algorithms in geotechnical engineering: a short critical review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54, 5633–5673 (2021).

Zhu, C., Li, X., Wang, C., Zhang, B. & Li, B. Deep learning-based coseismic deformation estimation from InSAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–10 (2024).

Xin, J., Xu, W., Cao, B., Wang, T. & Zhang, S. A deep-learning-based MAC for integrating channel access, rate adaptation and channel switch. (2024).

Javed, M. F. et al. Evaluation of machine learning models for predicting TiO2 photocatalytic degradation of air contaminants. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–25 (2024).

Khawaja, L. et al. Indirect estimation of resilient modulus (Mr) of subgrade soil: Gene expression programming vs multi expression programming. Structures 66, 106837 (2024).

Ahmed, H. U. et al. Innovative modeling techniques including MEP, ANN and FQ to forecast the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete modified with nanoparticles. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 12453–12479 (2023).

Chang, X. et al. Single-objective and multi-objective flood interval forecasting considering interval fitting coefficients. Water Resour. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-024-03848-2 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Electric-field-driven printed 3D highly ordered microstructure with cell feature size promotes the maturation of engineered cardiac tissues. Adv. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202206264 (2023).

Hong, J., Gui, L. & Cao, J. Analysis and experimental verification of the tangential force effect on electromagnetic vibration of PM motor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 38, 1893–1902 (2023).

Liao, L. et al. Color image recovery using generalized matrix completion over higher-order finite dimensional algebra. Axioms 12, 954 (2023).

He, X. et al. Excellent microwave absorption performance of LaFeO3/Fe3O4/C perovskite composites with optimized structure and impedance matching. Carbon N Y 213, 118200 (2023).

Agatonovic-Kustrin, S. & Beresford, R. Basic concepts of artificial neural network (ANN) modeling and its application in pharmaceutical research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0731-7085(99)00272-1 (2000).

Pitts, W. & McCulloch, W. S. How we know universals the perception of auditory and visual forms. Bull Math. Biophys. 9, 127 (1947).

Kourgialas, N. N., Dokou, Z. & Karatzas, G. P. Statistical analysis and ANN modeling for predicting hydrological extremes under climate change scenarios: The example of a small Mediterranean agro-watershed. J. Environ. Manage. 154, 86 (2015).

Naresh Babu, K. V. & Edla, D. R. New algebraic activation function for multi-layered feed forward neural networks. IETE J. Res. 63, 71 (2017).

Das, S. K. Artificial neural networks in geotechnical engineering: modeling and application issues. Metaheuristics Water Geotech. Transp. Eng. 45, 231–267 (2013).

Tahani, M., Vakili, M. & Khosrojerdi, S. Experimental evaluation and ANN modeling of thermal conductivity of graphene oxide nanoplatelets/deionized water nanofluid. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 76, 358–365 (2016).

Koza: Genetic Programming: On the Programming of... - Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Genetic Programming%3A on the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection&publication_year=1992&author=J.R. Koza&author=J.R. Koza.

Chen, D., Zhao, T. & Xu, S. Single-stage multi-input buck type high-frequency link’s inverters with multiwinding and time-sharing power supply. IEEE Trans. Power Electron 37, 12763–12773 (2022).

Wang, T., Zhang, S., Yang, Q. & Liew, S. C. Account service network: A unified decentralized web 3.0 portal with credible anonymity. IEEE Netw. 37, 101–108 (2023).

Saridemir, M. Genetic programming approach for prediction of compressive strength of concretes containing rice husk ash. Constr. Build Mater. 24, 1911–1919 (2010).

Nazari, A. & Torgal, F. P. Modeling the compressive strength of geopolymeric binders by gene expression programming-GEP. Expert Syst. Appl. 40(14), 5427–5438 (2013).

Farooq, F., Ahmed, W., Akbar, A., Aslam, F. & Alyousef, R. Predictive modeling for sustainable high-performance concrete from industrial wastes: A comparison and optimization of models using ensemble learners. J Clean Prod 292, 126032 (2021).

Ferreira, C. Gene Expression Programming: Mathematical Modeling by an Artificial Intelligence (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Springer, 2006).

Tang, H. et al. Rational design of high-performance epoxy/expandable microsphere foam with outstanding mechanical, thermal, and dielectric properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.55502 (2024).

Khan, M. A. et al. Compressive strength of fly-ash-based geopolymer concrete by gene expression programming and random forest. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021(1), 6618407 (2021).

Jiang, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, D. & Shi, L. Online Pareto optimal control of mean-field stochastic multi-player systems using policy iteration. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 67(4), 140202 (2024).

Liu, Z., Xu, Z., Zheng, X., Zhao, Y. & Wang, J. 3D path planning in threat environment based on fuzzy logic. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46, 7021–7034 (2024).

Gandomi, A. H., Babanajad, S. K., Alavi, A. H. & Farnam, Y. Novel approach to strength modeling of concrete under triaxial compression. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 24(9), 1132–1143 (2012).

Kardani, N. et al. A novel improved Harris Hawks optimization algorithm coupled with ELM for predicting permeability of tight carbonates. Eng. Comput. 38, 4323–4346 (2022).

Shi, X. L. et al. A novel fiber-supported superbase catalyst in the spinning basket reactor for cleaner chemical fixation of CO2 with 2-aminobenzonitriles in water. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133204 (2022).

Alavi, A. H., Gandomi, A. H., Nejad, H. C., Mollahasani, A. & Rashed, A. Design equations for prediction of pressuremeter soil deformation moduli utilizing expression programming systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 23, 1771–1786 (2013).

Gandomi, A. H., Faramarzifar, A., Rezaee, P. G., Asghari, A. & Talatahari, S. New design equations for elastic modulus of concrete using multi expression programming. Taylor & Francis 21, 761–774 (2015).

Esmaeili-Falak, M. & SarkhaniBenemaran, R. Application of optimization-based regression analysis for evaluation of frost durability of recycled aggregate concrete. Struct. Concr. 25, 716–737 (2024).

Dawei, Y. et al. Structural engineering and mechanics. Struct. Eng. Mech. 86, 673 (2023).

Gordan, B., JahedArmaghani, D., Hajihassani, M. & Monjezi, M. Prediction of seismic slope stability through combination of particle swarm optimization and neural network. Eng. Comput. 32, 85–97 (2016).

Fei, R., Guo, Y., Li, J., Hu, B. & Yang, L. An improved BPNN method based on probability density for indoor location. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 106(5), 773–785 (2023).

Karim, R., Islam, Md. H., Datta, S. D. & Kashem, A. Synergistic effects of supplementary cementitious materials and compressive strength prediction of concrete using machine learning algorithms with SHAP and PDP analyses. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e02828 (2024).

Liu, X., Zhang, X., Wang, H. & Jiang, B. Laboratory testing and analysis of dynamic and static resilient modulus of subgrade soil under various influencing factors. Constr. Build. Mater. 195, 178–186 (2019).

Indraratna, B., Armaghani, D. J., Gomes Correia, A., Hunt, H. & Ngo, T. Prediction of resilient modulus of ballast under cyclic loading using machine learning techniques. Transp. Geotech. 38, 100895 (2023).

Pahno, S., Yang, J. J. & Kim, S. S. Use of machine learning algorithms to predict subgrade resilient modulus. Infrastructures 6, 78 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/72/44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Machine learning, Data Curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization, M.F.J.Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, L.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Machine learning, Data Curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing—Original Draft, Kennedy Onyelowe: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, H.A.: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, A.F. A.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, D.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khawaja, L., Asif, U., Onyelowe, K. et al. Development of machine learning models for forecasting the strength of resilient modulus of subgrade soil: genetic and artificial neural network approaches. Sci Rep 14, 18244 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69316-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interpretable XGBoost-based predictions of shear wave velocity from CPTu data

Marine Geophysical Research (2026)

-

Predicting the strength of microsilica lime stabilized sulfate sand using hybrid machine learning models optimized with sparrow search algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Back analysis of mechanical parameters based on GPSO-BP neural network and its application

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Identification of soil texture and color using machine learning algorithms and satellite imagery

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Prediction of swelling pressure of expansive soil using machine learning methods

Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (2025)