Abstract

Anastomotic stricture is a typical complication of esophageal atresia surgery. Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) has demonstrated multiorgan benefits, however, its efficacy in the esophagus remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate whether applying RIC after esophageal resection and anastomosis in rats could attenuate esophageal stricture and improve inflammation. Sixty-five male Sprague–Dawley rats were categorized into the following groups: controls with no surgery, resection and anastomosis only, resection and anastomosis with RIC once, and resection and anastomosis with RIC twice. RIC included three cycles of hind-limb ischemia followed by reperfusion. Inflammatory markers associated with the interleukin 6/Janus kinase/ signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (IL-6/JAK/STAT3) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha/nuclear factor-κB (TNF-α/NF-kB) signaling pathways were evaluated with RNA and protein works. The RIC groups showed significantly lower stricture rates, lower inflammatory markers levels than the resection and anastomosis-only group. The RIC groups had significantly lower IL-6 and TNFa levels than the resection and anastomosis-only group, confirming the inhibitory role of remote ischemic conditioning in the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 and TNF-α/NF-kB signaling pathways. RIC after esophageal resection and anastomosis can reduce the inflammatory response, improving strictures at the esophageal anastomosis site, to be a novel noninvasive intervention for reducing esophageal anastomotic strictures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anastomotic stricture, with an incidence of 20–50%, is the most typical complication after the surgical treatment for esophageal atresia1,2,3,4. These strictures lead to issues such as growth and developmental limitations due to dietary restrictions, which can be resolved using various nonsurgical treatments such as balloon dilatation, bougienation, and steroid injection5,6,7. However, stricture resection and repeat anastomosis are performed when these methods are ineffective8,9.

Notably, various causes of postoperative esophageal anastomotic strictures have been reported, including inflammation and focal ischemia due to insufficient blood supply to the esophagus10,11. The healing process of esophageal anastomoses is similar to that observed in other tissues and encompasses three phases: inflammation (days 0–4), proliferation (days 5–10), and remodeling (days 10 and onward)12. Similar to the wound healing process, if the inflammatory phase of acute wound healing persists due to pressure-induced tissue trauma, bacterial overgrowth, or ischemic reperfusion injury, progression to chronic wound healing and associated complications may become unavoidable13,14. However, definitive evidence of inflammation in esophageal anastomotic strictures is unavailable.

Cytokines are critical in several intracellular signaling pathways. For example, interleukins (ILs), a cytokine, interact with many cell types, leading to cancer15. Cancers often accompany inflammation and chronic inflammation triggered by decreased tolerance of the target tissue; therefore, ILs could also influence surgical treatment16. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in the progression of the immune system17,18,19 and tumors20,21,22,23. It binds to receptors and induces tyrosine kinases such as the Janus kinase (JAK). The phosphorylation of JAK activates docking sites for recruiting the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) proteins, thereby activating STAT3 signaling24,25. Therefore, IL-6 contributes to the systemic inflammatory response and tumorigenesis by activating the JAK/STAT3 pathway26. Notably, IL-6 and activated STAT3 levels are increased in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC)27,28, showing that intrinsic inflammation may contribute to bile acid (BA) carcinogenesis through IL-6 and STAT329.

Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]) are associated with complex signaling pathways in several diseases. In particular, TNF is a critical factor in various disease states, including chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, and tumorigenesis30,31. The TNF superfamily significantly mediates cell survival, differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis, and necrosis by modulating multiple pathways through nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), JUN N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)32. NF-κB activation induces phosphorylation of nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor alpha (IκBα) from the IκBα kinase (IKK) complex, after which phosphorylated IκBα is ubiquitinated and degraded by releasing NF-κB dimers that translocate to the target gene’s nucleus. Notably, the dysregulation of NF-κB signaling is associated with inflammation and cancer33,34,35. In addition, TNF-α is highly expressed in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, and NF-κB overexpression is upregulated in patients with BA and EAC36,37,38. Therefore, understanding the effect of the TNF-α-activated NF-κB signal pathway on esophageal disease is crucial for devising therapeutic strategies.

Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC), which reportedly provides multiorgan benefits39, involves repetitive cycles of temporary ischemia and reperfusion in peripheral areas to increase systemic blood supply. Angiogenesis is the main factor responsible for these benefits40,41,42; however, some studies have reported reduced intestinal inflammation and increased intestinal regeneration, especially in the small intestine and colon, when using RIC39,43,44,45. Notably, several studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of RIC in acute inflammation, such as in a necrotizing enterocolitis mouse model46 or a case with middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion, highlighting the anti-inflammatory effects associated with the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 (Nrf2/HO-1) signaling pathway47. Another recent study showed the efficacy of RIC in patients with contact dermatitis by suppressing CD8 + T lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration and reducing IL-17 secretion48.

However, to our knowledge, the benefits achieved through RIC in the esophagus are yet to be reported. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate whether applying RIC after esophageal resection and anastomosis in rats improves esophageal strictures and its related pathways by focusing on the inflammatory processes.

Methods

Animals

This study procured 65 male Sprague–Dawley rats (aged 11 weeks and weighing 320–400 g) from the laboratory animal supply facility (KOATECH, Pyeongtaek, Korea). Notably, all rats were provided unrestricted food and water pre and postoperatively. The experiments were approved by the Seoul National University Hospital Animal Ethics Committee (IACUC No. 22-0029-S1A3(1)), and all methods followed their guidelines and regulations. This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

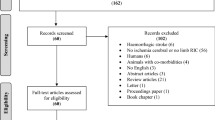

Experimental design and RIC procedure

The rats were categorized into the following four groups: (a) a control group with no surgery (n = 5), (b) resection and anastomosis only (R&A only, n = 20), (c) resection and anastomosis with RIC immediately after closing the neck incision (RIC1, n = 20), and (d) resection and anastomosis with RIC immediately after closing the incision and on postoperative day 2 (RIC2, n = 20). The surgical procedure involved exposing the cervical esophagus, which was identified posterolaterally to the trachea, through a median neck incision. Subsequently, esophageal resection (1 mm) and anastomosis using 8–0 Prolene sutures were performed under a microscope (Fig. 1A). RIC included three cycles of 5 min left hind-limb ischemia and 5 min of reperfusion (Fig. 1B). The rats were sacrificed on postoperative day 7, and the entire esophagus was collected.

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) and analysis (LASCA)

Laser speckle contrast imaging was used to assess blood flow in anesthetized rats, which were maintained at a body temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C. Recordings were conducted before and after inducing hind limb ischemia (Fig. 2). Blood flow decreased during ischemia and reperfusion was observed after 5 min of ischemia in the right hind limb (Fig. 2A). Successful hind limb ischemia was defined when the blood flow ratio reduced to approximately 50% of the baseline (Fig. 2B). Blood flow increased in the cervical esophagus during ischemia and was maintained throughout the ischemia–reperfusion session (Fig. 2C–E). Blood flow images were acquired using a PeriCam high-resolution LSCI system (PSI system, Perimed, Sweden) with a 2448 × 2048-pixel charge-coupled device (CCD) camera positioned 5 cm above the esophagus. The acquired images were analyzed using PIMSoft software (Perimed, Sweden).

Measurement of blood flow using a laser speckle contrast imaging. (A) Representative images of blood flow in the right hind limb 5 min after one cycle of ischemia (middle image) and 5 min after reperfusion (right image) using laser speckle. (B) Representative recordings of blood flow: baseline, 5 min after one cycle of ischemia, and 5 min after reperfusion in the right hind limb. (C) Representative images of blood flow in the cervical esophagus immediately after closing the neck incision, 5 min after one cycle of ischemia (middle image), and 5 min after reperfusion (right image) using laser speckle. (D) Representative recordings of blood flow: baseline, 5 min after one cycle of ischemia, and 5 min after reperfusion in the cervical esophagus. (E) Quantification of the relative ROI (n = 10). (ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001).

Body weight measurement and esophageal stricture evaluation

The rats were weighed daily pre and postoperatively until euthanasia, after which the collected esophagus was filled with contrast material, and radiographs were taken to assess the degree of stricture. The extent of the anastomotic stricture was assessed using the stricture index employed by Said et al.49, denoted as SI = (A-a)/A, where “A” represents the diameter of the lower esophageal pouch and “a” signifies the stricture diameter.

Histological examination

The esophageal tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and dehydrated using a descending series of ethanol at room temperature. Notably, all tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm-thick sections. Using a standard protocol, each tissue section was subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The histological slides were then analyzed using an Olympus BX43 microscope and imaged using the MT iSolution Lite software. All histological samples were scored anonymously and counted in 10 random fields. These H&E-stained slides were generated to assess the anastomosis site, with scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 indicating the absence of findings, mild manifestations, moderate conditions, and marked alterations, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed on esophageal tissues using the Envision + system (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The esophageal tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a descending series of ethanol solutions at room temperature. The endogenous peroxidase complex activity was quenched using a methanol/3% hydrogen peroxide solution. The samples were then incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: anti-pSTAT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 1:50 dilution), anti-STAT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:50 dilution), and anti-p65 NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA; 1:400 dilution). The samples were stained with primary antibodies and incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody and streptavidin-peroxidase complex for 1 h. The final product was developed using a 3,3’-diaminobenzidine liquid substrate system tetrahydrochloride (DAKO; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Two independent observers performed all histological assessments and obtained tissue images using an Olympus BX43 microscope. They measured and quantified the samples using the Image J software (Version 1.54j, https://imagej.net/ij).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

We extracted total RNA from the esophageal tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Rockford, IL, USA). Total RNA (2 μg) was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using the Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and applied using the QuantStudio™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer pairs used for PCR included IL-6 (F: CCAATTTCCAATGCTCTCCT; R: ACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA), TNFα (F: GACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGA; R: ACTGATGAGAGGGAGGCCAT), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (F: AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG; R: GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT). We normalized the messenger RNA (mRNA) levels to the internal reference gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and the results are represented as folds of the baseline levels in the control group. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and relative expression levels were calculated using the delta-delta Ct method.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from homogenized esophageal tissues using Tissue Extraction Reagent I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (100:1 ratio). All protein concentrations were measured with the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal quantities of protein (40 μg) were used for electrophoresis on a 10–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. The separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Merck Millipore, Burlington, VT, USA) and blocked with 5% skim milk in Tween® 20 Detergent (TBS-T) buffer at room temperature. Membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated overnight at 4 °C with corresponding primary antibodies: anti-phosphorylated JAK (Cell signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), anti-JAK2 (Cell signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), anti-phosphorylated STAT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:500 dilution), anti-STAT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000 dilution), anti-IL6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000 dilution), anti-phosphorylation-p65 NF-κB (Cell signaling Technology, 1:500 dilution), anti-p65 NF-κB (Cell signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), anti-IKKα/β (Cell signaling Technology, 1:500 dilution), anti-phosphorylation IκBα (Cell signaling Technology, 1:500 dilution), anti-IκBα (Cell signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), and anti-GAPDH (Assaygenie, 1:5000 dilution). After corresponding primary antibody incubation, proteins were further incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies (each 1:10,000 dilution). Membranes were washed thrice with TBS-T buffer, and proteins were detected using SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate ECL kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein images were visualized using the enhanced ImageQuant™ LAS 4000mini (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and differences between the groups were assessed using Student’s t-test when comparing between two groups. Comparisons between categorical variables of three groups were performed with the Kruskal–Wallis due to the non-parametric nature of the data followed by the post hoc Bonferroni Correction. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Body weight and esophageal stricture

The rats’ weights decreased immediately postoperatively until postoperative day 2 and then increased from day 3 onwards (Fig. 3A). The extent of weight loss was lowest in the RIC2 group and highest in the group that did not undergo RIC. Furthermore, weight gain was highest in the RIC2 group and lowest in the group that did not undergo RIC. In all experimental groups, the weight recovered to approximately 90% of the preoperative weight by postoperative day 7. Notably, the anastomotic site stricture rates were 0.49, 0.37, and 0.29 for the R&A-only, RIC1, and RIC2 groups, respectively, with statistically significant differences (Fig. 3B). Moreover, we observed a significant increase in body weight following esophageal resection and anastomosis and a notable reduction in anastomotic strictures in rats that underwent RIC.

Histologic evaluation

The R&A-only, RIC1, and RIC2 groups had inflammation scores of 2.6, 2.0, and 2.1, respectively. However, the scores of the two groups that underwent RIC were lower than those of the R&A-only group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Notably, IHC staining performed according to the inflammatory pathway revealed that p-STAT3 expression was lower in RIC1 and RIC2 slides than in R&A-only slides, and this pattern was similarly observed in NF-kB staining (Fig. 4).

Esophageal tissue sections from the control, R&A-only, RIC1, and RIC2 groups. (A–D) Histological analysis of the rat esophageal tissue from each group using hematoxylin and eosin staining. (E–P) Immunohistochemical analysis of phosphorylated STAT3, STAT3, and nuclear factor-κB expression in the rat esophageal tissue from each group. Images were obtained for each rat (n = 5), and representative images are shown (scale bar = 200 µm). Abbreviations: R&A, resection and anastomosis; RIC1, remote ischemic conditioning performed once postoperatively; RIC2, remote ischemic conditioning performed twice postoperatively.

Effect of RIC on the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway after esophageal resection surgery

Upon mRNA level evaluation, our results showed that IL-6 increased in the R&A group and significantly decreased in the RIC1 and RIC2 groups (Fig. 5A). To evaluate the factors associated with the STAT3 signaling pathway, we used western blotting to analyze the levels of phosphorylation of JAK and STAT3, as well as the levels of JAK and IL-6 (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 1). We found that the level of STAT3 and JAK phosphorylation was significantly lower in the RIC1 and RIC2 groups than in the R&A group. In addition, the IL-6 levels were significantly reduced in RIC2 groups than in the R&A group (Fig. 5C,D). These data suggest that the IL-6/STAT3 pathway is crucial in esophageal resection and anastomosis, and RIC can inhibit IL-6/STAT3 signaling.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis of factors associated with IL-6. (A) Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of IL-6 in the rat esophageal tissue from the control, R&A-only, RIC1, and RIC2 groups (n = 10). The results are normalized to values obtained for the control group (value = 1). (B) Western blot analysis of p-JAK, JAK, p-STAT3, STAT3, and IL-6 in esophageal tissue samples from each group (n = 10). The relative band intensity is presented. (C, D) Quantification of western blot data from (B) using quantification software (Image J, Version 1.54j, https://imagej.net/ij), represented as the relative values of p-JAK compared with JAK and p-STAT3 compared with STAT3. All Data are means ± SEM p‐value was calculated by two‐way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests and also presented compared with the R&A-only group (n = 10) (ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001). Abbreviations: R&A resection and anastomosis; RIC1 remote ischemic conditioning performed once postoperatively; RIC2 remote ischemic conditioning performed twice postoperatively; SEM standard error of the mean; JAK Janus kinase; p-JAK phosphorylated JAK; p-STAT3 phosphorylated STAT3; IL-6 interleukin-6.

Effect of RIC on the TNF/NF-kB signaling pathway after esophageal resection surgery

We found that the mRNA level of TNFα was higher in the R&A-only group than in the control group; however, it was lower in the RIC1 and RIC2 groups than in the R&A-only group (Fig. 6A). To further analyze this interaction, we used western blotting to investigate the levels of NF-kB/p65, IkBα, IKKα/β, and their levels of phosphorylation (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Fig. 1). Our data showed that the R&A-only group had higher levels of phosphorylated NF-kB/p65, IkBα, and IKKα/β than all RIC groups (Fig. 6C,D,E), suggesting that RIC inhibited the production of inflammatory cytokines constituting the TNF/NF-kB signaling pathway after esophageal resection surgery.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis of factors associated with TNFα. (A) Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of TNFα in the rat esophageal tissue from the control, R&A-only, RIC1, and RIC2 groups (n = 10). The results are normalized to values obtained for the control group (value = 1). (B) Western blot analysis of p-p65/NF-kB, NF-kB, p-IkBa, IkBa, p-IKKa/b, and IKKa in esophageal tissue from each group (n = 10). The relative band intensity is presented. (C–E) Quantification of western blot data from (B) using quantification software (Image J, Version 1.54j, https://imagej.net/ij), represented as the relative values of p-p65/NF-kB compared with NF-kB, p-IkBa compared with IkBa, and p-IKKa/b compared with IKKa. All Data are means ± SEM p‐value was calculated by two‐way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests and also presented compared with the R&A-only group (n = 10) (ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001). Abbreviations: R&A, resection and anastomosis, RIC1, remote ischemic conditioning performed once postoperatively, RIC2, remote ischemic conditioning performed twice postoperatively, SEM standard error of the mean; p-p65 phosphorylated p65, p-IkBa phosphorylated IkBa, p-IKKa/b phosphorylated IKKa, NF-kB nuclear factor-κB, TNFα tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Discussion

Experimental results

In this study, rats subjected to esophageal resection and anastomosis exhibited anastomotic stricture 1 week postoperatively and showed improvement with the RIC procedure. We investigated factors associated with known inflammatory pathways to identify those contributing to ameliorating anastomotic strictures. We discovered increased multiple factors linked with the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 and TNF/NF-kB signaling pathways of inflammation at the anastomosis site and its vicinity following esophageal resection and anastomosis alone. However, these factors exhibited a subsequent decrease when RIC was implemented. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate RIC’s potential in facilitating recovery from esophageal anastomotic strictures.

Stricture formation and its mechanisms in esophageal anastomosis

The occurrence of strictures after esophageal anastomosis is a widely recognized multifactorial phenomenon, with local disruption of the blood supply being a contributing factor10,11. Anastomotic healing typically progresses through three phases: an inflammatory phase characterized by hemostasis and debridement during the initial 1–4 days after suturing, a proliferative phase involving angiogenesis and collagen synthesis (spanning up to 2 weeks), and a remodeling phase50. The formation of the anastomotic line is significantly influenced by the inflammatory phase, characterized by the infiltration of inflammatory cells and the production of tissue growth factors within the anastomotic site51. Following esophageal anastomosis formation, this inflammatory response and the potential inflammation caused by sutures may contribute to excessive fibrosis and granulation. This could lead to the subsequent formation of anastomotic strictures during the remodeling process, possibly causing anastomotic strictures in the esophagus.

Previous studies have reported the diverse effects exerted by RIC on various factors. For example, in a mouse model replicating midgut volvulus, a previous study reported reduced levels of intestinal inflammation-related cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) in an experimental group subjected to RIC52. This is consistent with our study’s results, suggesting that RIC ameliorates inflammation and improves esophageal anastomotic strictures associated with inflammation. These findings confirm that RIC may prevent the development of anastomotic strictures following esophageal resection and anastomosis, representing a novel outcome of our study.

Anti-inflammatory effects of RIC

Our results confirm the anti-inflammatory effects of RIC reported by previous animal studies investigating ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) scenarios. Notably, a previous study showed that compared with a control group, the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α exhibited increased myocardial infarction (MI) model utilizing SD rats; however, when RIC was applied, a significant reduction in the serum levels of these cytokines was observed45. Similarly, another study examining an MI rat model revealed that RIC was associated with decreased proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 in serum and infarcted myocardium, whereas IL-10 was higher in the RIC group than in the control group44.

RIC attenuated the release of proinflammatory cytokines in various research models, including models of cerebral infarction and renal, pulmonary, and hepatic reperfusion injuries43. For example, in a cohort of aged rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion, RIC significantly reduced IL-1, IL-6, and IFN-γ levels in plasma and cerebral tissues53. In addition, in a murine model of hepatic I/R injury, RIC significantly decreased the levels of intrinsic liver enzymes, IL-6, and TNF-α54. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory effect of RIC was mediated by the high mobility group box 1/Toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB pathway, a well-established mechanism governing cytokine release54.

NF-κB is associated with various inflammatory activities and possesses numerous anti-apoptotic actions, presenting challenges regarding upstream inhibition in inflammatory diseases35,55. In a mouse model of acute lung injury, RIC resulted in reduced NF-κB activation by acting on Iκβα proteins; in turn, this resulted in decreased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-656, which is consistent with our study results. However, previous research has shown the anti-inflammatory effects of RIC, but no existing studies have confirmed the effects of RIC on esophageal anastomosis or other esophageal diseases. Our study shows that RIC reduces the inflammatory response during the immediate post-anastomotic inflammatory phase. Therefore, this suggests that the severity of subsequent fibrosis and the consequent formation of strictures may not worsen if RIC is applied after esophageal resection and anastomosis.

Factors explaining other potential effects of RIC

Previous studies have reported that RIC improves circulation, thereby protecting organs at risk of ischemia39. RIC enhances collateral circulation in a murine model of focal cerebral ischemia, increases cerebral blood flow during stroke recovery in a rat model of ischemic brain injury, and improves coronary collateral circulation in a rabbit model of myocardial ischemia40,41,42. The results of the present study have confirmed the anti-inflammatory role of RIC; however, future studies investigating the potential effects of RIC on enhanced blood flow around the anastomosis site, including angiogenesis, are required.

Conclusion

We demonstrated the role of RIC in improving anastomosis strictures in a rat model of esophageal resection and anastomosis. The effects of RIC were likely attributable to the observed reduction in cytokines, indicating a decreased inflammatory response at the anastomosis site. However, RIC’s complete mechanism of action is not fully understood and may involve regulating inflammation. Therefore, it is essential to investigate further whether the known effects of RIC, such as angiogenesis, contribute to improved strictures at the anastomosis site. Our findings imply that RIC can be a potential therapeutic option for enhancing recovery from strictures following esophageal anastomosis. However, further investigations are required to fully assess the various aspects of RIC and its impact on esophageal stricture improvement.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baird, R., Laberge, J. M. & Levesque, D. Anastomotic stricture after esophageal atresia repair: A critical review of recent literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 23, 204–213 (2013).

Konkin, D. E., O’Hali, W. A., Webber, E. M. & Blair, G. K. Outcomes in esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 38, 1726–1729 (2003).

Lilja, H. E. & Wester, T. Outcome in neonates with esophageal atresia treated over the last 20 years. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 24, 531–536 (2008).

Touloukian, R. J. & Seashore, J. H. Thirty-five-year institutional experience with end-to-side repair for esophageal atresia. Arch. Surg. 139, 371–374 (2004) (discussion 374).

Ko, H. K. et al. Balloon dilation of anastomotic strictures secondary to surgical repair of esophageal atresia in a pediatric population: Long-term results. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 17, 1327–1333 (2006).

Lang, T., Hümmer, H. P. & Behrens, R. Balloon dilation is preferable to bougienage in children with esophageal atresia. Endoscopy. 33, 329–335 (2001).

Ngo, P. D. et al. Intralesional steroid injection therapy for esophageal anastomotic stricture following esophageal atresia repair. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 70, 462–467 (2020).

Koivusalo, A. I., Pakarinen, M. P., Lindahl, H. G. & Rintala, R. J. Revisional surgery for recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula and anastomotic complications after repair of esophageal atresia in 258 infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 250–254 (2015).

Zhu, H., Shen, C., Xiao, X., Dong, K. & Zheng, S. Reoperation for anastomotic complications of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 2012–2015 (2015).

Bombeck, C. T., Boyd, D. R. & Nyhus, L. M. Esophageal trauma. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 52, 219–230 (1972).

Storey, C. F. & Boyer, J. L. Lye stricture of the esophagus–esophageal replacement using the right and transverse colon. Am. J. Surg. 100, 71–84 (1960).

Bonavina, L. Progress in the esophagogastric anastomosis and the challenges of minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery. Ann. Transl. Med. 9, 907 (2021).

Diegelmann, R. F. Excessive neutrophils characterize chronic pressure ulcers. Wound Repair. Regen. 11, 490–495 (2003).

Menke, N. B., Ward, K. R., Witten, T. M., Bonchev, D. G. & Diegelmann, R. F. Impaired wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 25, 19–25 (2007).

Li, J., Huang, L., Zhao, H., Yan, Y. & Lu, J. The role of interleukins in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 2323–2339 (2020).

Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int. Immunol. 33, 127–148 (2021).

Chou, D. B. et al. Stromal-derived IL-6 alters the balance of myeloerythroid progenitors during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 123–131 (2012).

Hunter, C. A. & Jones, S. A. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 16, 448–457 (2015).

Liu, F., Poursine-Laurent, J., Wu, H. Y. & Link, D. C. Interleukin-6 and the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor are major independent regulators of granulopoiesis in vivo but are not required for lineage commitment or terminal differentiation. Blood. 90, 2583–2590 (1997).

Abana, C. O. et al. IL-6 variant is associated with metastasis in breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE 12, e0181725 (2017).

Ge, J. et al. Long non-coding RNA promotes ovarian cancer cells progression via IL-6/STAT3 pathway. J. Ovarian Res. 13, 72 (2020).

Jinushi, M. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages regulate tumorigenicity and anticancer drug responses of cancer stem/initiating cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 12425–12430 (2011).

Su, K. et al. A novel positive feedback regulation between long noncoding RNA UICC and IL-6/STAT3 signaling promotes cervical cancer progression. Am. J. Cancer Res. 8, 1176–1189 (2018).

Kim, B. H., Yi, E. H. & Ye, S. K. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 as a therapeutic target for cancer and the tumor microenvironment. Arch. Pharm. Res. 39, 1085–1099 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Tyrphostin B42 attenuates trichostatin A-mediated resistance in pancreatic cancer cells by antagonizing IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Oncol. Rep. 39, 1892–1900 (2018).

Zimmers, T. A., Fishel, M. L. & Bonetto, A. STAT3 in the systemic inflammation of cancer cachexia. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 54, 28–41 (2016).

Dvorak, K. et al. Activation of the interleukin-6/STAT 3 antiapoptotic pathway in esophageal cells by bile acids and low pH: Relevance to Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5305–5313 (2007).

Zhang, H. Y. et al. Cancer-related inflammation and Barrett’s carcinogenesis: interleukin-6 and STAT3 mediate apoptotic resistance in transformed Barrett’s cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastr. L. 300, G454–G460 (2011).

Huang, B., Lang, X. & Li, X. The role of IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Front Oncol. 12, 1023177 (2022).

Holbrook, J., Lara-Reyna, S., Jarosz-Griffiths, H. & McDermott, M. Tumour necrosis factor signalling in health and disease. F1000Res. 8, F1000 (2019).

Schröfelbauer, B. & Hoffmann, A. How do pleiotropic kinase hubs mediate specific signaling by TNFR superfamily members?. Immunol. Rev. 244, 29–43 (2011).

Aggarwal, B. B. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: A double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 745–756 (2003).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 140, 883–899 (2010).

Lee, H. R., Choi, J., Lee, S. H., Cho, M. L. & Jue, D. M. Intracelluar delivery of A20 protein inhibits TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. Protein Expres Purif. 143, 14–19 (2018).

Yamamoto, Y. & Gaynor, R. B. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 135–142 (2001).

Blanchard, C. et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: Transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 120, 1292–1300 (2007).

Goyal, A. & Cheng, E. Recent discoveries and emerging therapeutics in eosinophilic esophagitis. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 7, 21–32 (2016).

Straumann, A., Bauer, M., Fischer, B., Blaser, K. & Simon, H. U. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T2-type allergic inflammatory response. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 108, 954–961 (2001).

Koike, Y. et al. Remote ischemic conditioning counteracts the intestinal damage of necrotizing enterocolitis by improving intestinal microcirculation. Nat. Commun. 11, 4950 (2020).

Kitagawa, K., Saitoh, M., Ishizuka, K. & Shimizu, S. Remote limb ischemic conditioning during cerebral ischemia reduces infarct size through enhanced collateral circulation in murine focal cerebral ischemia. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. 27, 831–838 (2018).

Ren, C. H. et al. Limb ischemic conditioning improved cognitive deficits via eNOS-dependent augmentation of angiogenesis after chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. Aging Dis. 9, 869–879 (2018).

Zheng, Y., Lu, X., Li, J. N., Zhang, Q. S. & Reinhardt, J. D. Impact of remote physiological ischemic training on vascular endothelial growth factor, endothelial progenitor cells and coronary angiogenesis after myocardial ischemia. Int. J. Cardiol. 177, 894–901 (2014).

Pearce, L., Davidson, S. M. & Yellon, D. M. Does remote ischaemic conditioning reduce inflammation? A focus on innate immunity and cytokine response. Basic Res. Cardiol. 116, 12 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Combined vagal stimulation and limb remote ischemic perconditioning enhances cardioprotection via an anti-inflammatory pathway. Inflammation. 38, 1748–1760 (2015).

Zhang, J. R. et al. Remote ischaemic preconditioning and sevoflurane postcondition.ing synergistically protect rats from myocardial injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion partly via inhibition TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 41, 22–32 (2017).

Alganabi, M. et al. Remote ischemic conditioning causes CD4 T cells shift towards reduced cell-mediated inflammation. Pediatr Surg. Int. 38, 657–664 (2022).

Sun, Y. Y. et al. Remote ischemic conditioning attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in MCAO mice. Redox Biol. 66, 102852 (2023).

Gunduz, O. et al. Anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects of remote ischaemic postconditioning in a mouse model of experimental allergic contact dermatitis. Medicina-Lithuania. 59, 1816 (2023).

Said, M. et al. Balloon dilatation of anastomotic strictures secondary to surgical repair of oesophageal atresia. Br. J. Radiol. 76, 26–31 (2003).

Morgan, R. B. & Shogan, B. D. The science of anastomotic healing. Semin. Colon Rectal. Surg. 33, 100879 (2022).

Adam, A. B., Ozdamar, M. Y., Esen, H. H. & Gunel, E. Local effects of epidermal growth factor on the wound healing in esophageal anastomosis: An experimental study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 99, 8–12 (2017).

Zhu, H. et al. Remote ischemic conditioning avoids the development of intestinal damage after ischemia reperfusion by reducing intestinal inflammation and increasing intestinal regeneration. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 37, 333–337 (2021).

Du, X. N. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and 2α have beneficial effects in remote ischemic preconditioning against stroke by modulating inflammatory responses in aged rats. Front Aging Neurosci. 12, 54 (2020).

Zendedel, A. et al. Activation and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome by intrathecal application of SDF-1a in a spinal cord injury model. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 3063–3075 (2016).

Toldo, S. & Abbate, A. The NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial infarction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 203–214 (2018).

Kim, Y. H. et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning ameliorates indirect acute lung injury by modulating phosphorylation of IκBα in mice. J. Int. Med. Res. 47, 936–950 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JKY and HK had full access to all of the data in the study and were responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: JKY, HL, DK, HK Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: JKY, HL Drafting of the manuscript: JKY, HK Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: JKY, HL, HK Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Hyun-Young Kim.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Youn, J.K., Lee, HR., Ko, D. et al. Attenuation of esophageal anastomotic stricture through remote ischemic conditioning in a rat model. Sci Rep 14, 18481 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69386-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69386-4