Abstract

Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, integral for sustainable energy, face challenges in forecasting due to the unpredictable nature of environmental factors influencing energy output. This study explores five distinct machine learning (ML) models which are built and compared to predict energy production based on four independent weather variables: wind speed, relative humidity, ambient temperature, and solar irradiation. The evaluated models include multiple linear regression (MLR), decision tree regression (DTR), random forest regression (RFR), support vector regression (SVR), and multi-layer perceptron (MLP). These models were hyperparameter tuned using chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA) for a performance appraisal. The models are subsequently validated on the data from a 264 kWp PV system, installed at the Applied Science University (ASU) in Amman, Jordan. Of all 5 models, MLP shows best root mean square error (RMSE), with the corresponding value of 0.503, followed by mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.397 and a coefficient of determination (R2) value of 0.99 in predicting energy from the observed environmental parameters. Finally, the process highlights the fact that fine-tuning of ML models for improved prediction accuracy in energy production domain still involves the use of advanced optimization techniques like ChOA, compared with other widely used optimization algorithms from the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photovoltaic (PV) systems are recognized as one of the ways to a sustainable future, combating the issue of climate change, with the promotion of environment-friendly practices in societies1. The process by which the solar energy content in the sunlight is harnessed and directly converted into electricity from sunlight2 holds great merit into PV systems globally3. Environmental and economic topics cover most of the attention, along with the generation of electricity from the PV technologies4,5. The use of PV technology positively contributes to the ongoing concern of the depletion of finite resources, which not only helps to combat climate change and CO2 emissions6, but also reduces negative health effects on the human health associated with the use of conventional energy generation methods7.

The importance of PV forecasting in the many applications of PVs is practiced for the proper management and maintenance of the PV systems worldwide. Effective utility grid management is realized from this process, given the immense ability to predict the expected output in energy generation8. PV forecasting aids in scheduling maintenance activities, allowing for minimal disruption to energy supply9. Appropriate forecasting at the advanced establishment of renewable sources of energy, such as solar, will become important in ensuring seamless integration of these sources into the grid and is key toward a more sustainable energy future10.

However, this application does not come without its obstacles. One significant challenge is the inherent variability and uncertainty associated with solar energy generation11, caused from factors such as weather patterns12, cloud cover13, or seasonal variability14. These are the main factors responsible for the model errors, mainly when long-term forecasting is involved. There is not always a challenge in techniques but also in information, as the availability of reliable input data is crucial for accurate forecasting15. At its core, methods for dealing with the challenges of PV forecasting are based on physics or data. Physics-based models, reasonably strong theoretically, are far from trivial in implementation, since they deal with a lot of parameters and assumptions about the underlying conditions. On the other hand, data-driven models, using machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), become necessary for solving all the problems of the earlier-mentioned methods.

Data-driven models have notably advanced the accuracy of solar energy production forecasts16,17. Initially, simple models were widely used for such predictions. For instance, traditional regression models or simple time series analysis techniques were common choices18. Nevertheless, such simple models encounter challenges in accurately capturing the complexities of solar energy generation patterns leading to a shift towards ensemble methods like random forest (RF) and Decision trees (DTs). Over time, advancements in ML and DL techniques have contributed to improving these predictions. This is true in19, where the authors analyzed 180 papers in the PV forecasting literature and found that hybrid models achieve best accuracy and could become predominant in the future. Several studies have analyzed the performance of single ensemble models in the context of PV forecasting, for example, the use of a single ensemble model is highlighted in20 where the authors used RF to forecast daily PV power generation and achieved a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 2.83% and 3.89% for clear sky and cloudy sky days, respectively. Asiedu et al.21 compared the performance of 8 single and hybrid ML models for PV energy forecasting over different time horizons. The authors concluded that the selection of models based on the time horizon is necessary, with artificial neural network (ANN) outperforming in day-ahead forecasting with a coefficient of determination (R2) value of 0.8702. Kaffash & Deconinck22 compared ANN and support vector machine (SVM) for hourly day ahead forecasting and found that SVM achieves better results in most time stamps.

While single ML and DL models have demonstrated significant predictive capabilities, researchers have increasingly explored the combination of multiple models to further enhance forecasting accuracy. The majority of such combinations often represent an ensemble of hybrid models that can capture the strengths of individual models but make them work better. Examples from the literature include Khan et al.23 who proposed an improved DL algorithm that combines ANN, long short-term memory (LSTM), and XGBoost for day-ahead forecast across several time horizons. The proposed DSE-XGB method outperforms individual DL algorithms with an improvement in R2 value by 10–12%. Lu24 proposed a hybrid forecasting approach, \(K\)-IAOA-DNN, that combines K-Means+ + for similarity identification and a deep neural network (DNN) with input and output adjusting structures. The model achieved an average root mean square error (RMSE), normalized-RMSE (nRMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) values of 14.43 kW, 0.048, and 9.53 kW, respectively. Asari et al.25 proposed a novel hybrid methodology for day-ahead photovoltaic power forecasting, which can either use a clear sky model or an ANN, depending on the day-ahead weather forecasting. The results of the hybrid approach are more accurate over single models. The nRMSE, RMSE, and mean bias error (MBE) are reported at 0.5041, 1.9041, and − 0.3398, respectively. Kumar et al.26 developed a novel analytical technique for predicting solar PV power output using one and two diode models with 3, 5, and 7 parameters, relying only on manufacturer data. Validated through both indoor and outdoor experiments in India, the 7-parameter model showed the highest accuracy. It achieved an RMSE of 0.02, outperforming the 5 and 3-parameter models. Singhal et al.27 developed a novel time series ANN model to predict PV energy output. This model improves three existing models: nonlinear auto regression (NAR), NAR with external input (NARX), and Nonlinear input–output (NIOP). They evaluated three ANN training algorithms using MSE, RMSE, and nRMSE. The analysis showed that the NARX model with Bayesian regularization training algorithm (BRTA) achieved the highest accuracy. It had the lowest error rate of 15.5% compared to the other models.

This development process in PV forecasting is, therefore, open, whether it be in the use of single models or hybrid ones. However, the inestimable value of setting internal parameters elaborately in model construction requires a series of careful procedures that demand optimal performance. This calls for precise optimization techniques and the algorithms for defining these parameters. Noteworthy methods in this domain are the particle swarm optimization (PSO) and the genetic algorithm (GA), among others. For instance, Gu et al.28 found that the Whale Optimization Algorithm – least square SVM (WOA-LSSVM) model outperformed several other models and optimization techniques including standard LSTM/LSSVM and PSO-LSSVM. Kothona et al.29 introduced a hybrid Adam-unified PSO optimizer for day-ahead PV power forecasting, outperforming traditional methods by up to 22.6%. VanDeventer et al.30 found that a GA-SVM model achieves best results compared to conventional SVM model. Ratshilengo et al.31 compared GA against recurrent neural networks (RNN) and k-nearest neighbors (k-NN). The main findings included the GA model exhibiting the best conditional predictive ability based on RMSE and relative-RMSE metrics, while the RNN model outperformed in terms of MAE and relative-MAE metrics. Nuvvula et al.32 assessed and optimized hybrid renewable energy systems in Visakhapatnam, India, focusing on floating and rooftop solar, wind energy, and battery storage. They identified 105 MW of floating solar, 260 MW of rooftop PV, and 62 MW of wind potential using tools like Bhuvan GIS and Google Earth. Their multi-objective optimization minimized costs, power loss, and emissions, achieving a loss of power supply between 0.285% and 0.3% and a levelized cost of energy (LCOE) ranging from $0.09 to $0.11/kW. In a subsequent study, Nuvvula et al.33 evaluated four renewable energy technologies in Visakhapatnam, India, identifying a potential of 439 MW. The technologies assessed included floating solar, bifacial rooftops, wind energy conversion, and waste-to-energy plants. By applying mutation-enabled Adaptive Local Attractor-based quantum behaved particle swarm optimization (ALA-QPSO) and integrating battery storage solutions and waste-to-energy systems, they optimized PV and wind systems. The optimal configuration achieved a levelized cost of $0.0539, a high reliability with a 0.049% loss of power supply, and required a $40.5 million investment, partially funded through renewable energy services.

From the above-reported research works, boosting the performance of ML and DL techniques via the integration of optimization techniques, integrated to optimally set their hyperparameters, is evident in the literature for predicting solar PV energy production. This work aims to add to the existing body of knowledge a further novel contribution in this field via the investigation of various ML and DL techniques effectively combined with one of the latest optimization techniques (nature-inspired techniques), aiming to boost the prediction accuracy of the solar energy production of solar PV plants. Specifically, five distinct ML models that are multiple linear regression (MLR), decision tree regression (DTR), random forest regression (RFR), support vector regression (SVR), and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) have been examined and the impact of their integration with the chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA) has been discussed. The effectiveness of this contribution is verified regarding data from a real case study of a 264 kWp PV system installed at the Applied Science University (ASU) in Amman, Jordan, while resorting to various performance metrics from the literature including RMSE, MAE, and R2.

Material and methods

This section presents the case study examined in this work (Section “Material”) and outlines the various data-driven techniques investigated for estimating the daily energy production of a solar PV system (Section “Methods”):

Material

Solar PV system

Data in this study are provided from a solar PV system installed at top the engineering building at ASU, in Amman, Jordan, at 32.04N and 35.90E. The system has a DC capacity of 264 kWp and an AC capacity of 231 kW. The panels utilized in the system belong to the YL 245P-29b-PC model, each with a capacity of 245Wp. The installation tilt angle is set at 11° with an azimuth angle of −36° (east). Table 1 provides the standard characteristics of the PV modules. Figure 1 illustrates a map highlighting the ASU campus, showcasing the location of the engineering building, weather station, and Renewable Energy Center. The map was generated using Google Earth Pro, version 7.3 (available at https://www.google.com/earth/about/versions/)34.

ASU campus map, highlighting the engineering building, weather station and renewable energy center. Generated using Google Earth Pro, version 7.3 (available at https://www.google.com/earth/about/versions/)34.

Data collection

The PV data were collected at one-hour resolution (measured in kW) from May 16, 2015, to December 31, 2018. Then, it was aggregated as daily points (measured in kWh), resulting in a total of 1326 numbers of daily data points that used in this study. The PV production data were recorded by SMA SUNNY TRIPOWER 17 kW and 10 kW inverters and subsequently transmitted to a supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system at the Renewable Energy Center on the ASU campus. Other meteorological variables, namely wind speed (\(WS\)), relative humidity (\(RH\)), ambient temperature (\({T}_{amb}\)), and solar irradiation (\(Irr\)), were measured from the weather station inside the campus. Humidity measurements were obtained using a calibrated hygrometer with a range of 0 to 100% and a deviation of ± 2%. The ambient temperature measurements are carried out using a precise thermometer calibrated in a range of − 30 to 70 °C with deviation ± 0.2 °C. The wind speed measurements are recorded using an anemometer with a range of at least 0.3 m/s to 75 m/s and an accuracy of 1% of the measured value. The measurements of radiation are made by using a pyranometer with a sensitivity range of 7–14 µV/W/m2 and a maximum relative uncertainty of 1% and a maximum operational irradiance of 4000 W/m2. It’s worth noting that the weather station is 171m away from the engineering building. The weather station’s proximity to the PV system (171 m) ensures high accuracy of the meteorological data, closely reflecting the actual conditions at the PV system site.

These parameters are used to enhance the predictions by capturing the seasonal variations in the PV system’s performance, ensuring the model adapts to changes throughout the year and improves the accuracy of daily energy production predictions. It is worth noting that the selected parameters are the most commonly used and highly influential factors affecting the prediction of PV output. They have been widely used in the literature, with several studies demonstrating their significant impact on PV performance prediction35,36,37,38.

Climate

The data collection site, ASU, is established in Amman, Jordan, which experiences a Mediterranean climate characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. Figure 2 represents an average of the solar resources and the temperature profile at ASU from 2016 to 2018. Notably, the average all-year temperature is 17.63 °C, and the mean annual global horizontal irradiation stands at 2040.2 kWh/m2.

Methods

In this section, we present the five distinct ML models investigated in this work, along with the ChOA used to enhance their prediction accuracy for the daily solar PV production of the ASU solar PV system. The detailed mechanisms of the five ML models investigated in this work, the ChOA technique, as well as the ML models hyperparameter optimization are presented in Section “ML Approaches”, “Chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA)”, and “ML models hyperparameter optimization”, respectively.

ML approaches

In this study, five different ML approaches are employed, as described in the following subsections, to predict energy production based on the four independent weather variables: \(WS\), \(RH\), \({T}_{amb}\), and \(Irr\). The selection of these five approaches, ranging from linear to highly non-linear approach, provides a balanced and comprehensive framework for assessing and improving solar energy production prediction. Every approach has a different set of benefits that add to a comprehensive comprehension of the modeling challenge and the possibility of increasing forecast accuracy. For instance, MLR is selected to provide a benchmark for comparing the performance of more complex models. DTR for its ease of implementation and ability to handle non-linear relationships, making it effective for understanding feature significance and interactions. RFR is selected for its robustness against noisy data, strong performance, and capability to handle large datasets, also providing insights into feature importance. SVR is included for its effectiveness in high-dimensional spaces and ability to manage non-linearity, which helps in extracting complex patterns from the data. Finally, MLP is selected for its adaptability and ability to learn from extensive data, making it well-suited for identifying intricate relationships and patterns.

A. Multiple linear regression (MLR)

MLR is a statistical approach that utilizes multiple independent variables to estimate the dependent variable. The main target of MLR is to model the correlation between input features and response variable. MLR extends upon the scope of linear regression (LR), which involves a single predictor, to account for multiple independent variables simultaneously39. MLR models are widely used in forecasting due to their simplicity in implementation, interpretable computations, and ability to identify anomalies or outliers within a given set of predictor variables. The mathematical form of MLR is presented in Eq. (1).

where the model’s outcome and input features are denoted by \(Y\) and \(X\), respectively, \({b}_{0}\) is a constant parameter, and \({b}_{i}\) represents a regression coefficient for each \(i\)-th independent variable, \(i=1,\dots ,j\). The model’s error term (residual) is denoted by \(\varepsilon\).

B. Decision tree regression (DTR)

The DT is a ML technique that can be used for both regression and classification tasks. The DT functions similarly to a flowchart, with the feature values moving through a tree-like model, and the branches directing the values towards a decision. Each branch contains criteria similar to an if-else statement. DTs are available in two types: regression and classification. In classification tasks, a decision tree typically takes the properties of an event as input, while for regression, the input data usually comprises continuous values or time series events. By estimating the probability of an outcome based on the influence of features, the DTR models forecast the output. To define the intended output, DTR considers the entropy function and information gain as pertinent metrics for each characteristic. Entropy (\(E\)) is used to assess the homogeneity of a random sample collection, while information gain calculates the amount of an attribute, which helps in class estimation40. The following Eqs. (2) and (3) can be used to express the entropy and information gain, respectively:

where the ratio of data points and total number of classes are denoted by \(R{D}_{i}\) and \({N}_{c}\), respectively. \({S}_{i}\) stands for the sample, and \({X}_{a}\) represents the attribute.

C. Random forest regression (RFR)

RFR is a general supervised ML approach that is used for both classification and regression tasks. RFR is an ensemble learning approach for regression problems, where it trains a very large number of decision trees41. The final prediction in RFR is averaged from individual predictions obtained from each tree in the ensemble. Next, a generalization error threshold is developed in RFR so as to prevent overfitting. The out-of-bag (OOB) error, representing the error for training points excluded from the bootstrap training samples, is used to estimate the generalization error. This OOB estimation process, similar to \(N\)-fold cross-validation, assists RFR in mitigating overfitting. In the end, the final projections are the average of all the trees’ predictions. The mathematical representation of RFR is depicted in Eq. (4):

where \(Y\) represents the model outcome and \({N}_{T}\) denotes the total number of trees.

D. Support vector regression (SVR)

SVR is a supervised ML approach that extends the SVM to address the regression task. The basic components of SVR include a hyperplane supported by minimum and maximum margin lines42, as well as support vectors, as depicted in Eq. (5):

where \(x\) represents the independent variable, \(\omega\) and b are weight vectors, and \(\varphi \left(x\right)\) denotes the mapping function. When dealing with a multidimensional dataset, \(Y\) may have an infinite number of prediction options. Therefore, to address the optimization problem depicted in Eq. (6), a tolerance limit is introduced:

where \(C\) represents a positive regularization parameter that balances the trade-off between prediction error and the flatness of the function, \(\omega\) is the intense loss parameter, and \({\xi }_{i} , {\xi }_{i}^{*}\) are slack variables used to minimize the inaccuracy between the hyperplane’s sensitive zones. The optimization methods for resolving the dual nonlinear issue can be reformulated in Eq. (7), which also expresses the sensitive zones using Lagrange multipliers:

where \({\alpha }_{i}\) and \({\alpha }_{i}^{*}\) denote Lagrange multipliers, and \(k\left({x}_{i} . {x}_{j}\right)\) is kernel function used to solve the nonlinear task. In this model, the radial basis function (RBF), as depicted in Eq. (8), was selected due to its adaptability and capacity to represent complex correlations between the independent and dependent variables:

where \(\gamma\) represents a tuning kernel parameter and \({\left|{x}_{i}-{x}_{j}\right|}^{2}\) denotes the Euclidean distance between \({x}_{i}\) and \({x}_{j}\). Finally, Eq. (9) illustrates the SVR decision function:

E. Multi-layer perceptron (MLP)

MLP is an ANN with several layers of neurons. These neurons typically use nonlinear activation functions, which help the network recognize and comprehend intricate patterns within the data. Generally, a network is organized into layers, starting with the input layer where independent variables are initially added. The subsequent stage involves hidden layers where calculations are performed. Finally, the output layer where predictions are produced43. The mathematical representation of the linear combination of these layers is presented in Eq. (10):

where \({f}_{a}\) represents the activation function of the hidden neuron, that is the leaky Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU). The number of hidden and output neurons is denoted by \(m\) and \(n\), respectively. The weights for the neurons of the output layer and hidden layer are represented by \({w}_{i}\) and \({w}_{j}\), respectively. The input layer bias is denoted as \({b}_{1}\), and the output layer bias is denoted as \({b}_{2}\). A training method known as back-propagation (BP) uses the most recent weight and bias information to retrain each neuron. This procedure aims to minimize the prediction error of the output layer. The updated weight is presented in Eq. (11):

where \({w}^{*}\) and \(w\) represent the new and old weight, respectively. \(\alpha\) is the learning rate, and \(\frac{\partial e}{\partial w}\) is the derivative of the error with respect to the weight. Equation (12) shows the error function:

where \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) and \({y}_{i}\) represent the prediction and actual value, respectively.

Chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA)

The ChOA is a metaheuristic algorithm designed to replicate the cooperative hunting behavior of chimpanzees in the wild44. In optimization tasks, prey hunting is used in the ChOA to identify the optimal solution. The hunting process in ChOA is divided into four main phases: driving, blocking, chasing, and attacking. Initially, ChOA starts by generating a random population of chimps. These chimps are then randomly assigned to four groups: attacker, chaser, barrier, and driver. Equations (13) and (14) have been proposed to model the driving and chasing of prey:

where the position vectors of the chimpanzee and the prey are denoted by \({X}_{c}\) and \({X}_{p}\), respectively. The variable \(t\) represents the current iteration, and \(a\), \(m\), and \(c\) are coefficient vectors computed through Eqs. (15–17):

where \({r}_{1}\) and \({r}_{2}\) are random vectors within the range [0, 1]. The parameter vector \(f\) decreases non-linearly from 2.5 to 0 during the iterations, and m represents a chaotic vector calculated using a distinct chaotic map. This vector signifies the impact of social stimuli on the pursuing chimpanzee.

During the hunting step, the chimpanzees initially detect the prey’s position with the assistance of the driver, blocker, and chaser chimpanzees. Subsequently, the attackers engage in the hunting during the exploitation process. In this phase, the prey’s position is estimated by the attacker, barrier, chaser, and driver chimpanzees, while the remaining chimpanzees update their positions relative to the prey. This process is detailed in Eqs. (18–20):

where the first, second, third, and fourth best agents are denoted by \({X}_{Attacher}\), \({X}_{Barrier}\), \({X}_{Chaser}\), and \({X}_{Driver}\), respectively. \({X}_{t+1}\) represents the updated position of each chimp. Additionally, to establish the exploration process, the parameter “\(a\)”, where values of “\(a\)” greater than 1 or less than − 1 cause the chimps and prey to diverge. Conversely, when “\(a\)” has values between + 1 and − 1, it promotes convergence between the chimps and prey, leading to improved exploitation. Furthermore, the parameter “\(c\)” assists the algorithm in executing the exploration process.

Following the conclusion of the hunt, the four groups of chimps gather, and their ensuing social interactions, such as group support and courtship, lead them to temporarily set aside their hunting duties. This results in chaotic behavior as they compete for access to the meat. This chaotic behavior in the final stage aids the algorithm in addressing issues like local optimization and slow convergence, particularly when solving high-dimensional problems. To model this social behavior, chaotic maps are employed, as described in Eq. (21):

where \(\mu\) is a random value between 0 and 1.

ML models hyperparameter optimization

The performance of ML algorithms is primarily influenced by two types of factors: model parameters and hyperparameters. Model parameters are the variables that the algorithm learns from the training data. For example, in SVM, decision boundaries are defined by these parameters and are adjusted during training to minimize the error between predicted and actual values.

In contrast, hyperparameters are external configurations set before the learning process begins, such as the learning rate in neural networks. Unlike model parameters, hyperparameters do not change during training but govern the learning process and affect the model’s overall behavior. Therefore, optimizing hyperparameters is essential, as they directly influence the training dynamics and can significantly impact the performance of ML models45.

To ensure optimal performance of the model, hyperparameter selection and optimization were performed experimentally, as shown in the following steps:

-

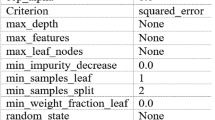

Initial hyperparameter ranges: For each ML model, the important hyperparameters of each ML model that significantly impact model performance and their initial ranges are determined based on previous studies and preliminary experiments, as presented in Table 2.

-

ChOA optimizer: The ChOA was employed for hyperparameter tuning due to its effectiveness in exploring high-dimensional and complex search spaces. In addition, slow convergence rates and being trapped in local optima are issues that ChOA resolves44. The hypereparameter optimization presented in Eq. (22):

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {x^{*} = \arg min_{x \in X} f\left( x \right)} \\ \end{array}$$(22)

where \(f(x)\) represents the objective function (RMSE) that needs to be minimized. x is a hyperparameter value in search space X, and x* is the hyperparameter configuration that yields the optimal value of \(f(x)\).

-

Cross-Validation: To ensure the models’ robustness and generalizability, fivefold cross-validation was employed. The dataset was divided into five subsets, with four subsets used for training and the remaining subset used for validation. This process was repeated five times, with each subset serving as the validation set once. The model’s performance was evaluated by averaging the results across the five folds.

-

Optimal values selection: The optimal hyperparameters value were selected based on the cross-validation results. The set of hyperparameters that produced the lowest average RMSE across the five folds was chosen as the optimal set. This approach ensured that the selected hyperparameters generalized effectively to unseen data and did not overfit the training set.

-

Final model training: After identifying the optimal hyperparameters, the final models were trained using these parameters on the entire training dataset. The models were then evaluated on the test set to verify their robustness and performance.

The pseudocode of hyperparameters optimization process presented below:

Results and discussion

Figure 3 illustrates the flowchart showing the process of the ML models investigated in this work for the prediction task. Specifically, this study employs two distinct datasets for training and testing a predictive model designed to forecast energy production based on environmental variables. The initial training dataset consisted of 961 records, from which 13 were eliminated due to missing data during preprocessing, resulting in a final size of 948 records. This dataset encompasses four crucial environmental inputs: \(WS\), \(RH\), \({T}_{amb}\), and \(Irr\), along with the corresponding energy production output. Similarly, the testing dataset comprised 365 records, with 3 records removed due to missing data, resulting in a final size of 362 records. Both datasets underwent preprocessing steps to ensure the integrity and quality of the input data, including handling missing data, data cleaning (i.e., excluding the missing data from the analysis), and feature scaling or normalization (i.e., using the max–min normalization/scaling preprocessing technique). It is worth mentioning that the missing data were identified through thorough inspection of the complete dataset, and their causes were attributed to failures in measurement devices, network interruptions, and inverter breakdowns in the ASU solar PV system under study. Due to the insignificant amount of missing data (less than 2%) and the availability of sufficient data covering the inherent seasonality of the solar PV system, the overall representativeness of the dataset remained intact, and the exclusion of the missing data will not adversely impact the predictability of the investigated ML models.

The predictive model was trained with the train dataset such that it learns the relationships present between the environmental factors and energy production. The performance of the model was evaluated on the test dataset and its ability to generalize on unseen data was evaluated. It is also important to mention that the experiments were undertaken in a computer under MATLAB R2022a, Windows 11 64-bit, Intel Core i5-1135G7 of the 11th generation processor, 8 GB RAM. Numerous ML models were considered in establishing the above relationship. The ChOA optimization technique was employed to fine-tune the parameters of the models, with the goal of enhancing model performance.

Inputs correlation analysis

The correlation matrix provides a comprehensive view of the relationships between the independent variables (i.e., \(WS\), \(RH\), \({T}_{amb}\), and \(Irr\)) and the dependent variable (energy production). This understanding is essential for assessing the significance and impact of each variable on energy production, which is crucial for the development of precise predictive models. Figure 4 depicts the outcomes of the correlation matrix heatmap, illustrating the correlations between the independent variables and the response variable.

The following points can be deduced from Fig. 4 regarding input variable correlation:

-

Wind speed exhibits a weak positive correlation with all other variables, including energy production (0.31). This indicates that as wind speed increases, there is a slight tendency for energy production to increase. however, the weak correlations with other inputs, such as relative humidity (0.21), ambient temperature (0.19), and solar irradiation (0.32), indicate that wind speed does not have strong linear dependencies with these variables.

-

Relative humidity demonstrates a moderate negative correlation with ambient temperature (− 0.64) and solar irradiation (− 0.52), as well as energy production (− 0.48). These negative correlations indicate that higher humidity levels are associated with lower ambient temperatures, reduced solar irradiation, and consequently, lower energy production. This inverse relationship highlights the importance of incorporating humidity into the predictive model, as it significantly influences the other variables and the overall energy production.

-

Ambient temperature exhibits a strong positive correlation with solar irradiation (0.77) and energy production (0.71). These strong correlations indicate that higher ambient temperatures are closely associated with increased solar irradiation and higher energy production. Due to its substantial influence, ambient temperature is a key predictor for energy production, indicating that variations in temperature significantly impact energy output.

-

Solar irradiation emerges as the most significant predictor of energy production, with a highly robust positive correlation of 0.952. This indicates that enhancements in solar irradiation are almost directly mirrored by increases in energy production, highlighting its pivotal role as a key variable in the predictive model. Additionally, solar irradiation exhibits moderate correlations with wind speed (0.32) and negative correlations with humidity (-0.52), further emphasizing its central role in energy prediction.

Implications for model development

Based on Fig. 4, the correlation matrix reveals that while wind speed has a moderate positive impact on energy production, it is not the most influential predictor. the moderate negative correlations of humidity with energy production, ambient temperature, and solar irradiation suggest that higher humidity levels could result in reduced energy production, necessitating careful modeling to accommodate this inverse relationship. Ambient temperature, with its strong positive correlations with both solar irradiation and energy production, emerges as a significant predictor that will significantly influence the accuracy of predictive models.

Given the highly robust correlation between solar irradiation and energy production, models that can capture non-linear relationships and interactions among variables, such as RFR or MLP, may prove more effective. Additionally, addressing potential multicollinearity, particularly between ambient temperature and solar irradiation, will be crucial for constructing robust models.

Based on the correlation analysis performed, potential multicollinearity issues were identified, primarily between ambient temperature and solar irradiation, due to their strong positive correlation of 0.77. Multicollinearity, which can inflate the variance of coefficient estimates and destabilize the model, was addressed through several strategies.

Firstly, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for each predictor. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to transform the correlated features into a set of linearly uncorrelated components, thereby reducing dimensionality and mitigating multicollinearity. These methods ensured that the models remained robust and provided stable predictions, reducing the adverse effects of multicollinearity. This careful management facilitated the development of more accurate and reliable predictive models, as demonstrated by the improved performance metrics following hyperparameter optimization.

Model evaluation metrics

Three statistical metrics were deliberately selected to provide a thorough assessment of the techniques and address various aspects of error analysis. It is important to note that no single measurement can fully capture all performance characteristics of the ML techniques. Therefore, the inclusion of these three metrics allows for a flexible and comprehensive evaluation of multiple elements of the approaches’ effectiveness. The three statistical tests used in this investigation are as follows:

-

Root mean square error (\(RMSE\)). This metric calculates the square root of the average of the squared differences between the predicted values and the actual values. It represents the standard deviation of errors and can be used to compare models across different datasets.

-

Mean absolute error (\(MAE\)). This metric calculates the average of the absolute differences between the predicted and actual values. It provides a clear indication of the average error magnitude, regardless of their direction or orientation.

-

Coefficient of determination (\({R}^{2}\)). This metric represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables in ML models.

Table 3 displays the evaluation results of various ML models for both training and testing datasets prior to the optimization of ML parameters.

A graphical representation is employed to evaluate the reliability of the various ML models. By plotting the model’s predictions against the actual targets, Fig. 5 emphasizes the accuracy of the forecasts. This illustrates how effectively the ML models fit the data.

Hyperparameters, including gamma, learning rate, epsilon, number of hidden layers, and leaves number, are essential in shaping the behavior of ML algorithms. Optimization or fine-tuning involves the selection of suitable hyperparameters to achieve desirable outcomes and enhance the performance of ML models. The ChOA parameters included 50 as the number of chimps and 300 as the maximum iteration number. Table 4 presents the optimal parameters for the best ML models.

To further evaluate the effectiveness of ChOA, we compared its performance with two other widely used optimization algorithms: PSO and GA. The optimizers parameters presented in Table 5 and 250 as the maximum iteration number.

The performance of each optimizer for hyperparameters ML models tuning was presented in Fig. 6. The hyperparameters and their ranges were identical to those used in the ChOA experiments.

The results indicate that ChOA consistently outperformed PSO, and GA in optimizing hyperparameters for all ML models. ChOA achieved lower RMSE values, reflecting reduced prediction errors. Moreover, ChOA demonstrated greater efficiency, requiring fewer iterations to achieve optimal hyperparameters. This is attributed to the semi-deterministic nature of chaotic maps, which enhances exploitation and convergence speed.

For instance, in DTR, ChOA reached an RMSE of 1.902 in 25 iterations, while PSO and GA needed 47 and 104 iterations, respectively, showing that ChOA was 46.8% faster than PSO and 76.0% faster than GA. Similarly, in MLP, ChOA achieved an RMSE of 0.486 in 35 iterations, compared to PSO’s 0.561 in 45 iterations and GA’s 1.019 in 99 iterations, making ChOA 22.2% faster than PSO and 64.6% faster than GA. In RFR, ChOA reached an RMSE of 1.773 in 57 iterations, while PSO required 66 iterations for an RMSE of 1.805 (about 1.8% lower RMSE and 13.6% fewer iterations), and GA needed 131 iterations for an RMSE of 2.021 (approximately 12.3% lower RMSE and 56.5% fewer iterations). For SVR, ChOA achieved an RMSE of 0.657 in 19 iterations, compared to PSO’s 0.963 in 27 iterations (about 31.7% lower RMSE and 29.6% fewer iterations) and GA’s 1.419 in 88 iterations (approximately 53.7% lower RMSE and 78.4% fewer iterations).

These results highlight ChOA’s superior efficiency and accuracy and the ability to effectively balance exploration and exploitation. Thus, ChOA was adopted in this study to optimize ML models for predicting solar energy production.

Table 6 displays the evaluation results of the ML algorithms after fine-tuning the hyperparameters to enhance the performance of the ML approaches. Additionally, Fig. 7 depicts the performance of the various ML approaches after fine-tuning the hyperparameters, confirming the effectiveness of the optimization process in enhancing the models’ performance.

The hyperparameter optimization significantly enhanced the performance of ML models, as evidenced by improvements in key statistical metrics. For the DTR model, there were notable improvements: RMSE decreased by 22.4%, from 2.542 to 1.972; MAE dropped by 14.6%, from 2.034 to 1.737; and R2 increased by 5.3%, from 0.903 to 0.951. The RFR model also benefited, with RMSE reducing by 10.9%, from 2.061 to 1.837; MAE decreasing by 6.9%, from 1.906 to 1.774; and R2 rising by 1.7%, from 0.947 to 0.963. The SVR model experienced the most dramatic enhancement, with RMSE dropping by 78.6% from 3.827 to 0.818, MAE decreasing by 68.8%, from 2.293 to 0.716; and R2 improving significantly by 11.8%, from 0.874 to 0.977. Similarly, the MLP model exhibited remarkable enhancements, with RMSE falling by 73.6%, from 1.908 to 0.503; MAE reducing by 76.5%, from 1.688 to 0.397; and R2 increasing by 3.8%, from 0.954 to 0.99. These results highlight that hyperparameter optimization led to improved model performance, increased accuracy, and more reliable predictions across all models.

In summary, the assessment of different ML models for forecasting energy production, both prior to and following hyperparameter optimization, is compared and deliberated. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

Initially, MLR demonstrated reasonable predictive accuracy with \({R}^{2}\) values of 0.928 for training and 0.916 for testing. However, its performance is comparatively lower than other models, except for SVR, prior to fine-tuning parameters. This is attributed to the fact that MLR assumes a linear relationship between the input variables and the output, which may not fully capture the complexity of the data.

-

DTR exhibited strong performance with \({R}^{2}\) values of 0.943 for training and 0.903 for testing, indicating its ability to handle non-linear relationships more effectively than MLR. However, the model displayed indications of overfitting, constraining its generalization capability. On the other hand, RFR performed robust performance with (\({R}^{2}\) values of 0.952 for training and 0.947 for testing, as it addresses overfitting by averaging multiple decision trees, thereby improving generalization and prediction accuracy. Initially, SVR exhibited the poorest performance, with \({R}^{2}\) values of 0.887 for training and 0.874 for testing, along with high \(RMSE\) and \(MAE\) values. This was attributed to its sensitivity to parameter settings, which, if not optimized, could result in suboptimal performance. Conversely, the MLP demonstrated the most favorable pre-optimization performance, with \({R}^{2}\) values of 0.955 for training and 0.954 for testing. The MLP’s capacity to comprehend complex, non-linear relationships through multiple layers of neurons rendered it particularly effective even before optimization.

-

Following the hyperparameter optimization of the ML models, all models experienced performance improvements as a result of fine-tuning the hyperparameters using the ChOA. Particularly, DTR exhibited substantial enhancements, with the testing RMSE decreasing to 1.972 and \({R}^{2}\) increasing to 0.951. The optimization aided in reducing overfitting through improved parameter selection, thereby enhancing its capacity to generalize to unseen data.

-

The RFR model showed notable improvements, with \(RMSE\) values decreasing to 1.773 for training and 1.837 for testing, and \({R}^{2}\) values increasing to 0.964 for training and 0.963 for testing. The fine-tuning process enhanced the ensemble model’s robustness and accuracy by optimizing the number of trees and other hyperparameters. The SVR model experienced the most remarkable enhancement, with the testing \(RMSE\) dropping to 0.818 and R2 increasing to 0.977. The optimization fine-tuned crucial parameters such as the kernel, \(C\), and epsilon values, significantly improving its ability to capture complex patterns.

-

Following optimization, the MLP demonstrated outstanding performance, with \(RMSE\) values of 0.486 for training and 0.503 for testing, along with an impressive \({R}^{2}\) value of 0.99 for testing. This exceptional performance can be attributed to the optimization of parameters such as learning rate, number of hidden layers, and neurons per layer, which bolstered the model’s ability to learn from the data and generalize effectively.

Conclusions and future recommendations

This study presented a comparison of five data-driven models, that are the MLR, DTR, RFR, SVR, and MLP, optimized using the ChOA. Pre-optimization benchmarks and post-optimization outcomes are presented using data from a 264 kWp PV installed at ASU using the RMSE, MAE, and R2 metrics. The main findings of this work can be summarized as follows:

-

The correlation matrix highlights solar irradiation as the most influential predictor of energy production, with a very strong positive correlation of 0.952. This indicates that higher solar irradiation directly results in increased energy production, highlighting its crucial role in the predictive model. Ambient temperature also has a significant positive impact on both solar irradiation (0.77) and energy production (0.71), indicating that warmer conditions contribute to better solar energy capture.

-

Wind Speed exhibits a moderate positive influence, while Humidity negatively affects energy production. Understanding these relationships is crucial for the selection and fine-tuning of ML models to enhance prediction accuracy. Additionally, addressing potential multicollinearity issues will be essential for constructing robust models, ensuring that the interdependencies among variables are appropriately considered in the predictive analysis.

-

The optimization of hyperparameters significantly enhanced the performance of all ML models. The ChOA effectively fine-tuned the parameters, resulting in improved model fitting, reduced overfitting, and enhanced generalization compared to two other widely used optimization algorithms from the literature: PSO and GA. Specifically, the ChOA achieved the lowest prediction errors (in terms of RMSE) and demonstrated greater efficiency, requiring fewer iterations to achieve optimal hyperparameters.

-

The MLP, with its inherently complex structure, achieved the highest predictive accuracy, highlighting the significance of optimization in the development of ML models. Specifically, reaching 0.503, 0.397, and 0.99 in RMSE, MAE, and R2, respectively.

Finally, we recommend the following for future perspectives:

-

To investigate the potential of other advanced ML or DL models not included in this study and their impact on PV system power predictions, while also recognizing ChOA as an effective optimization technique. Ensemble approaches of combining several of these models may also be assessed.

-

Real-time predictive capabilities and operational efficiency of solar PV systems can be investigated via the integration of real-time weather data.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request from the corresponding author, Sameer Al-Dahidi.

Abbreviations

- ALA-QPSO:

-

Adaptive local attractor-based quantum behaved particle swarm optimization

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- ASU:

-

Applied Science University

- BP:

-

Back-propagation

- BRTA:

-

Bayesian regularization training algorithm

- ChOA:

-

Chimp optimization algorithm

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- DNN:

-

Deep neural network

- DTR:

-

DT regression

- DTs:

-

Decision trees

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- k-NN:

-

k-Nearest neighbors

- LCOE:

-

Levelized cost of energy

- LR:

-

Linear regression

- LSSVM:

-

Least square SVM

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- MAE :

-

Mean absolute error

- MAPE :

-

Mean absolute percentage error

- MBE :

-

Mean bias error

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- MLP:

-

Multi-layer perceptron

- MLR:

-

Multiple linear regression

- NAR:

-

Nonlinear auto regression

- NARX:

-

NAR with external input

- NIOP:

-

Nonlinear input–output

- nRMSE :

-

Normalized-RMSE

- OOB:

-

Out-of-bag

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PSO:

-

Particle swarm optimization

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- R 2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- RBF:

-

Radial basis function

- ReLU:

-

Rectified Linear Unit

- RF:

-

Random forest

- RFR:

-

RF regression

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- RMSE :

-

Root mean square error

- RNN:

-

Recurrent neural network

- SCADA:

-

Supervisory control and data acquisition

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- SVR:

-

Support vector regression

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WOA:

-

Whale Optimization Algorithm

- WS:

-

Wind speed

- \(a\), \(m\), \(c\) :

-

Coefficient vectors in ChOA

- \(b_{0}\) :

-

MLR model’s constant parameter

- \(b_{1}\), \(b_{2}\) :

-

The input and output layer biases in MLP

- \(b_{i}\) :

-

MLR model’s regression coefficient for each \(i\)-th independent variable, \(i = 1, \ldots ,j\)

- \(c\) :

-

A parameter assists the ChOA in executing the exploration process

- \(c_{1}\) :

-

Cognitive parameter in PSO optimizer

- \(c_{2}\) :

-

Social parameter in PSO optimizer

- \(C\) :

-

A positive regularization parameter in SVR

- \(E\) :

-

The entropy in the DTR model

- \(f\) :

-

Parameter vector in ChOA

- \(f\left( x \right)\) and \(x\) * :

-

Objective function and corresponding optimal hyperparameter configuration

- \(f_{a}\) :

-

The activation function of the hidden neuron in MLP

- \(Irr\) :

-

Solar irradiation

- \(k\left( {x_{i} . x_{j} } \right)\) :

-

Kernel function in SVR

- \(m\) :

-

A chaotic vector in ChOA

- \(m\), \(n\) :

-

The number of hidden and output neurons in MLP

- \(N_{c}\) :

-

The total number of classes in DTR

- \(N_{T}\) :

-

The total number of trees in RFR

- \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) :

-

Random vectors \(\in \left[ {0, \, 1} \right]\) in ChOA

- \(RD_{i}\) :

-

DTR model’s ratio of data points, \(i = 1, \ldots ,N\)

- \(S_{i}\) :

-

\(i\)-th sample in the DTR model, \(i = 1, \ldots ,N\)

- \(t\) :

-

The current iteration in ChOA

- \(T_{amb}\) :

-

Ambient temperature

- \(x\) :

-

The SVR independent variables

- \(X\) :

-

MLR model’s input features

- \(X_{a}\) :

-

The attribute in the DTR model

- \(X_{Attacher}\) :

-

The first best agent in ChOA

- \(X_{Barrier}\) :

-

The second best agent in ChOA

- \(X_{c}\) :

-

The position vectors of the chimpanzee in ChOA

- \(X_{Chaser}\) :

-

The third best agent in ChOA

- \(X_{Driver}\) :

-

The fourth best agent in ChOA

- \(X_{p}\) :

-

The prey in ChOA

- \(X_{t + 1}\) :

-

The updated position of each chimp in ChOA

- \(\left| {x_{i} - x_{j} } \right|^{2}\) :

-

The Euclidean distance between xi and xj in SVR

- \(w_{i}\), \(w_{j}\) :

-

The weights for the neurons of the output and hidden layers

- \(w^{*}\), \(w\) :

-

The new and old weight in MLP

- \(Y\) :

-

ML models’ outcome

- \(\hat{y}_{i}\), \(y_{i}\) :

-

The prediction and actual value in MLP

- \(\alpha\) :

-

The learning rate in MLP

- \(\alpha_{i}\) and \(\alpha_{i}^{*}\) :

-

Lagrange multipliers in SVR

- \(\gamma\) :

-

A tuning kernel parameter in SVR

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

MLR model’s error term (i.e., residual)

- \(\mu\) :

-

Random value \(\in \left[ {0, \, 1} \right]\) in ChOA

- \(\varphi \left( x \right)\) :

-

The SVR’s mapping function

- \(\omega\) :

-

The intense loss parameter in SVR

- \(\omega\) and b :

-

SVR’s weight vectors

- \(\xi_{i} , \xi_{i}^{*}\) :

-

Slack variables in SVR

- \(\frac{\partial e}{{\partial w}}\) :

-

The derivative of the error with respect to the weight in MLP

References

Victoria, M. et al. Solar photovoltaics is ready to power a sustainable future. Joule 5, 1041–1056 (2021).

Bayod-Rújula, A. A. Solar photovoltaics (PV). in Solar Hydrogen Production, Elsevier, 237–295, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814853-2.00008-4.

Heng, S. Y. et al. Artificial neural network model with different backpropagation algorithms and meteorological data for solar radiation prediction. Sci. Rep. 12, 10457 (2022).

Pérez, N. S. & Alonso-Montesinos, J. Economic and environmental solutions for the PV solar energy potential in Spain. J. Clean Prod. 413, 137489 (2023).

Wang, Z. & Fan, W. Economic and environmental impacts of photovoltaic power with the declining subsidy rate in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 87, 106535 (2021).

Kumar, V., Kumar Jethani, J. & Bohra, L. Combating climate change through renewable sources of electricity- A review of rooftop solar projects in India. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 60, 103526 (2023).

Pablo-Romero, M. del P., Román, R., Sánchez-Braza, A. & Yñiguez, R. Renewable energy, emissions, and health. in Renewable Energy - Utilisation and System Integration (InTech, 2016). https://doi.org/10.5772/61717.

Alcañiz, A., Grzebyk, D., Ziar, H. & Isabella, O. Trends and gaps in photovoltaic power forecasting with machine learning. Energy Rep. 9, 447–471 (2023).

Olivencia Polo, F. A., Ferrero Bermejo, J., Gómez Fernández, J. F. & Crespo Márquez, A. Failure mode prediction and energy forecasting of PV plants to assist dynamic maintenance tasks by ANN based models. Renew. Energy 81, 227–238 (2015).

Yang, D., Li, W., Yagli, G. M. & Srinivasan, D. Operational solar forecasting for grid integration: Standards, challenges, and outlook. Solar Energy 224, 930–937 (2021).

Raza, M. Q., Nadarajah, M. & Ekanayake, C. On recent advances in PV output power forecast. Solar Energy 136, 125–144 (2016).

Malvoni, M., De Giorgi, M. G. & Congedo, P. M. Forecasting of PV power generation using weather input data-preprocessing techniques. Energy Procedia 126, 651–658 (2017).

Pierro, M. et al. Progress in regional PV power forecasting: A sensitivity analysis on the Italian case study. Renew. Energy 189, 983–996 (2022).

Jiang, H. et al. Analysis and modeling of seasonal characteristics of renewable energy generation. Renew. Energy 219, 119414 (2023).

Ahmed, R., Sreeram, V., Mishra, Y. & Arif, M. D. A review and evaluation of the state-of-the-art in PV solar power forecasting: Techniques and optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 124, 109792 (2020).

Souabi, S., Chakir, A. & Tabaa, M. Data-driven prediction models of photovoltaic energy for smart grid applications. Energy Rep. 9, 90–105 (2023).

Fentis, A., Rafik, M., Bahatti, L., Bouattane, O. & Mestari, M. Data driven approach to forecast the next day aggregate production of scattered small rooftop solar photovoltaic systems without meteorological parameters. Energy Rep. 8, 3221–3233 (2022).

Ibrahim, S. et al. Linear regression model in estimating solar radiation in perlis. Energy Procedia 18, 1402–1412 (2012).

Nguyen, T. N. & Müsgens, F. What drives the accuracy of PV output forecasts?. Appl. Energy 323, 119603 (2022).

Meng, M. & Song, C. Daily photovoltaic power generation forecasting model based on random forest algorithm for north China in winter. Sustainability 12, 2247 (2020).

Asiedu, S. T., Nyarko, F. K. A., Boahen, S., Effah, F. B. & Asaaga, B. A. Machine learning forecasting of solar PV production using single and hybrid models over different time horizons. Heliyon 10, e28898 (2024).

Kaffash, M. & Deconinck, G. Ensemble machine learning forecaster for day ahead PV system generation. In 2019 IEEE 7th International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE) 92–96 (IEEE, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/SEGE.2019.8859918.

Khan, W., Walker, S. & Zeiler, W. Improved solar photovoltaic energy generation forecast using deep learning-based ensemble stacking approach. Energy 240, 122812 (2022).

Lu, X. Day-ahead photovoltaic power forecasting using hybrid K-Means++ and improved deep neural network. Measurement 220, 113208 (2023).

Asrari, A., Wu, T. X. & Ramos, B. A hybrid algorithm for short-term solar power prediction—sunshine state case study. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 8, 582–591 (2017).

Kumar, M., Malik, P., Chandel, R. & Chandel, S. S. Development of a novel solar PV module model for reliable power prediction under real outdoor conditions. Renew. Energy 217, 119224 (2023).

Singhal, A., Raina, G., Meena, D., Chaudhary, C. K. S. & Sinha, S. A comparative analysis of ANN based time series models for predicting PV output. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES) 1–6 (IEEE, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/PEDES56012.2022.10080149.

Gu, B., Shen, H., Lei, X., Hu, H. & Liu, X. Forecasting and uncertainty analysis of day-ahead photovoltaic power using a novel forecasting method. Appl. Energy 299, 117291 (2021).

Kothona, D., Panapakidis, I. P. & Christoforidis, G. C. Day-ahead photovoltaic power prediction based on a hybrid gradient descent and metaheuristic optimizer. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57, 103309 (2023).

VanDeventer, W. et al. Short-term PV power forecasting using hybrid GASVM technique. Renew. Energy 140, 367–379 (2019).

Ratshilengo, M., Sigauke, C. & Bere, A. Short-term solar power forecasting using genetic algorithms: An application using south african data. Appl. Sci. 11, 4214 (2021).

Nuvvula, R., Devaraj, E. & Srinivasa, K. T. A Comprehensive assessment of large-scale battery integrated hybrid renewable energy system to improve sustainability of a smart city. Energy Sour Part A: Recovery Util Environ Effects 1–22 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2021.1905109.

Nuvvula, R. S. S. et al. Multi-objective mutation-enabled adaptive local attractor quantum behaved particle swarm optimisation based optimal sizing of hybrid renewable energy system for smart cities in India. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 49, 101689 (2022).

Google Earth Pro, version 7.3. https://www.google.com/earth/about/versions/.

Hatamian, M., Panigrahi, B. & Dehury, C. K. Location-aware green energy availability forecasting for multiple time frames in smart buildings: The case of Estonia. Meas. Sens. 25, 100644 (2023).

Ma, M. et al. Multi-features fusion for short-term photovoltaic power prediction. Intell. Converg. Netw. 3, 311–324 (2022).

Jebli, I., Belouadha, F.-Z., Kabbaj, M. I. & Tilioua, A. Prediction of solar energy guided by pearson correlation using machine learning. Energy 224, 120109 (2021).

Luo, X., Zhang, D. & Zhu, X. Deep learning based forecasting of photovoltaic power generation by incorporating domain knowledge. Energy 225, 120240 (2021).

Maulud, D. & Abdulazeez, A. M. A review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 1, 140–147 (2020).

Tangirala, S. Evaluating the impact of GINI index and information gain on classification using decision tree classifier algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 11, 612–619 (2020).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Awad, M. & Khanna, R. Efficient learning machines: Theories, concepts, and applications for engineers and system designers (Springer nature, 2015).

Kruse, R., Mostaghim, S., Borgelt, C., Braune, C. & Steinbrecher, M. (2022) Multi-layer Perceptrons BT - computational intelligence: A methodological introduction. In (Kruse, R., Mostaghim, S., Borgelt, C., Braune, C. & Steinbrecher, M. eds.), Springer International Publishing, 53–124

Khishe, M. & Mosavi, M. R. Chimp optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 149, 113338 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models based on bayesian optimization. J. Electr. Sci. Technol. 17, 26–40 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Renewable Energy Center at the ASU for sharing the solar PV dataset with us for research purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A-D.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. M.A.: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision. H.A.: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. B.R.: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. A.A.: Investigation, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Dahidi, S., Alrbai, M., Alahmer, H. et al. Enhancing solar photovoltaic energy production prediction using diverse machine learning models tuned with the chimp optimization algorithm. Sci Rep 14, 18583 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69544-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69544-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An interpretable statistical approach to photovoltaic power forecasting using factor analysis and ridge regression

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Innovative approaches to solar energy forecasting: unveiling the power of hybrid models and machine learning algorithms for photovoltaic power optimization

The Journal of Supercomputing (2025)

-

Fault analysis and detection on multiple points in transmission line through Mho relay and its data prediction through LSTM technique

Discover Artificial Intelligence (2025)

-

Proactive thermal management of photovoltaic systems using nanofluid cooling and advanced machine learning models

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)