Abstract

The acoustic black hole (ABH) structure exhibits remarkable energy focalization above a given cut-on frequency, offering potential for broadband vibration suppression in structures. However, its energy focusing properties diminish significantly below this cut-on frequency. Therefore, it is crucial to enhance the vibration attenuation capabilities of ABH structures within the low frequency range. This study presents a numerical investigation into the impact of thin-walled structures with embedded ABHs and distributed dynamic vibration absorbers (DVAs) on low frequency broadband vibration reduction. Initially, the focusing characteristics of the ABH thin-walled structure is analyzed, aiding in the attached position of DVAs. Furthermore, the influence of the design parameters and attached position of DVA on the broadband damping effect of the structure is explored. The findings indicate that DVAs designed for low frequencies can achieve significant vibration attenuation across the entire frequency spectrum, including low frequencies, when installed at specific focusing positions. When compared to the position with the maximum vibration response, while the attenuation of the low frequency common amplitude value is slightly reduced, greater vibration attenuation across the entire frequency band is achieved. This research offers valuable insights into optimizing the integration of DVAs with ABHs in thin-walled structures for enhanced broadband vibration attenuation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In various industrial applications, effective reduction of the unnecessary vibration of mechanical structures such as beams and plates is an essential issue. The classical method of passive vibration reduction typically involves the use of high-mass damping layers and tuned mass dampers1. These methods have been extensively researched and demonstrated to be effective. However, their implementation can lead to significant mass increase, which can be detrimental in various sectors of the transportation industry. As a result, significant interest lies in the development of vibration reduction technologies that limit mass increase.

In recent years, the acoustic black hole (ABH) has gained widespread attention as a novel structure for vibration and noise suppression. The ABH structure is a special type of variable thickness geometric structure, where the propagation speed of the bending wave generated inside the structure decreases as the thickness reduces due to external excitation. As the thickness approaches zero, the bending wave velocity reaches zero, and the cumulative phase of the wave increases infinitely. This leads to a concentration or “focusing” of the bending wave near the tip of the structure, which is referred to as the energy focusing effect2,3,4,5. Leveraging the energy focusing effect of the ABH structure, targeted damping measures can be taken in the focal region to achieve efficient vibration and noise reduction with minimal mass increase.

In the study of targeted damping measures for ABH, researchers commonly utilize damping layers or piezoelectric transducers for energy absorption or recovery. Incorporating a small amount of damping material into the ABH structure enables absorption of incident wave energy, reduction of wave reflection, and enhancement of energy dissipation rate6,7,8,9,10. Nevertheless, the damping effectiveness of a damping layer weakens as the frequency decreases11. It is worth noting that for thin-walled structures, the dimensions of the structure limit the use of ABH, resulting in relatively low vibration damping effectiveness, particularly at low frequencies12,13. Strictly speaking, there is a cut-on frequency below which the effectiveness of ABH decreases significantly, rendering it invalid14. Modifications to ABH characteristic parameters, while reducing the cut-on frequency to some extent, remain necessary within the scope of traditional linear ABH design.

Thus, improving the vibration damping effectiveness of the ABH structure in the low-frequency range has become a research focus in recent years. On the one hand, nonlinear mechanisms can be used to transfer energy from low frequencies (where ABH is ineffective) to high frequencies (where ABH is very efficient). Geometric nonlinearity has been successfully studied as a means to achieve this transfer in the work of Denis et al.15. Further, Li et al. proposed the VI-ABH7,8,16, which transforms a linear mechanism into a strongly nonlinear one and redistributes energy among all frequencies, resulting in reduced resonant amplitude values of low frequencies. On the other hand, the use of ABH in composite structures is often employed to enhance vibration damping performance in the low frequency range. Zhao17 has investigated the combination of ABH with Passive Constrained Layer Damping (PCLD) in the design of a sandwich structure. The sandwich structure involved the ABH viscoelastic structure arranged periodically between two rigid plates of uniform thickness, resulting in a vibration reduction within a relatively low frequency range. Alternatively, Chen et al.18 have proposed a novel approach that couples the ABH beam with a negative stiffness element (NS-ABH beam). The findings reveal that the NS-ABH beam is capable of achieving a notable reduction in vibration levels below the cut-on frequency, while still retaining the ABH effect at higher frequencies. Gao et al.19 have introduced the soft ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) material embedded into the ABH composite beam, and revealed its low-frequency vibration attenuation properties. The mass oscillator20 and smaller ABH unit21 have been proposed and embedded into ABH composite beam respectively, and the similar low-frequency vibration attenuation characteristics have been revealed.

Moreover, taking special localized measures at the end of the ABH structure can further reduce its low frequency response. Deng22,23 introduced a method that a set of periodic local resonators are attached to an ABH plate, which can extend the performance of ABH plates to lower frequencies. Wan et al.24,25 have utilized piezoelectric shunt damper to suppress ABH structure vibrations, implementing shunt damping with blocking circuits on one side of the central region of a two-dimensional ABH structure, and successfully suppressing four resonance peaks within the low-frequency range. Additionally, Raybaud et al.26,27 have applied a localized damping to the termination by means of elastic and damping point supports. This new type of device can generate low reflection coefficient values over wide and low frequency ranges.

However, until now, most of the research has focused on using ABH sandwich structures or additional complex devices to achieve low frequency vibration attenuation. When considering practical engineering applications, its application scope is often greatly limited. In the traditional vibration absorber, the combination of dynamic vibration absorber (DVA) and ABH is of little research. The DVA has a simpler structure and easier adjustment of the working band, so that it can achieve significant vibration attenuation in a specific frequency range (such as the low frequency band that ABH urgently needs to solve). The dynamic properties of acoustic black hole beam with DVA have been investigated in our previous study, and the results show that the application of ABH + DVA on a beam not only extends the single frequency-DVA vibration reduction capabilities to broadband applications but also reduces the low-frequency (below the cut-on frequency) vibration response of acoustic black hole beam, resulting in broadband vibration attenuation28. When two-dimensional ABH is embedded in thin-walled structures, previous research has investigated the vibration characteristics of plate structures with embedded ABHs and distributed DVAs29. However, only narrow-band damping in the low-frequency band has been achieved. To achieve the goal of low-frequency broadband vibration reduction through the integration of DVAs, the attached position of the DVAs is a critical factor. Therefore, the focusing position of two-dimensional ABH in thin-walled structures and its frequency-domain characteristics should be investigated. Based on the focusing characteristics, the influence of the attached position and tuning frequency of DVA on vibration attenuation would be studied, and its underlying mechanisms could be explained, thus showing the novelty of the present work.

This work includes five sections. In “Design and numerical modeling of ABHs + DVAs plate” section describes the model setting and verification for ABH thin plates. In “Results and discussion” section explores the focusing characteristics of the thin-walled structure embedded with four ABH elements through numerical simulations, providing justification for the DVAs attached position. Then the damping effect of the 4ABHs + 4DVAs thin plate structure across wide frequency band was investigated. Finally, “Conclusions” section summarizes the main findings of this study.

Design and numerical modeling of ABHs + DVAs plate

The thin-walled structure embedded with periodically ABHs construction

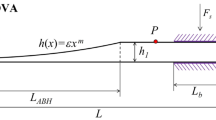

The thin-walled structure is composed of four two-dimensional ABH elements with radius of rABH arranged in two rows and two columns, as shown in Fig. 1a. The thin-walled structure has a side length of 2L and a thickness of h0. To assess the properties of ABH, a local coordinate system is employed, with the center of the ABH indentation serving as the origin. The radial thickness h(r) is examined as a function of the distance r from the center of ABH indentation, and is expressed as h(r) = εrm + hmin, where ε is a constant, m is a rational number greater than 2, and hmin is the minimum thickness, as shown in Fig. 1b. There are two types of attenuation method discussed in subsequent sections: coupled with DVA or coupled with damping layer, as shown in Fig. 1b,c. A DVA contains the mass part with mass of ma, a spring with stiffness of ka and a damping part with damping coefficient of ca. The damping layer with thickness of hd and radius of rd. For purposes of enhanced comprehension, a comprehensive and realistic DVA system is presented in the supplementary information.

Previous research has demonstrated that the acoustic black hole structure with fixed parameters can only exert a focusing effect when the frequency reaches the cut-on frequency16,30. The cut-on frequency can be determined by analyzing the wave dispersion within the acoustic black hole structure. Omar et al.14 considered ABH as a penetrable obstacle and obtained the cut-on frequency expression of 2D circular ABH through its scattering characteristics:

where n is circumferential order of an incoming cylindrical wave to a circular scatterer. When n is set to zero, the model becomes equivalent to the one-dimensional case, the cut-on frequency for the above ABH structure in this study can be simplified obtained as 1103 Hz, that is fcut-on = 1103 Hz.

Numerical modeling

In the subsequent sections, numerical simulations are utilized to initially investigate the focusing characteristics within frequency bands of the plate embedded with 4 ABH elements (depicted in Fig. 1). To facilitate comparison, a plate with uniform thickness of 5.2 mm and equivalent mass to that of ABHs was evaluated, designated as UTP. Subsequently, numerical simulations are utilized to assess the vibration attenuation performance of a thin-walled structure containing both four ABHs and four distributed DVAs (ABHs + DVAs), at the same time, the thin-walled structure containing both four ABHs and damping layer (ABHs + Damping) is also taken into account. Figure 1b provides a schematic diagram of installing a DVA in an ABH element, with one DVA installed in each ABH element and the installation location will be determined after focused analysis. The viscoelastic layers are positioned with the center of each ABH serving as the center of a circle and with a radius of rd, the thickness of these layers is hd, as shown in Fig. 1c. The simulation employed the material properties outlined in Table 1.

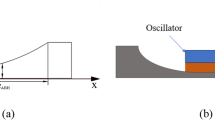

This paper employs the finite element method to delve into two significant aspects of structures. Initially, the simulation aids in the understanding of ABH’s physical phenomenon and it’s focusing characteristics. Secondly, it examines the physical basis of broadband vibration reduction achieved by ABHs + DVAs. To conduct these simulations, HYPERWORKS was utilized for preprocessing models and NASTRAN for dynamic analysis of structures. The Modal Frequency Response Analysis (MFRA) from NASTRAN code was used as the computing method for both focusing properties and vibration performance analysis. Since the simulations are 3D analysis, the tetrahedral elements were employed to establish the thin-walled structures, with an average global mesh size of 2 mm and minimum mesh size of 0.8 mm. For the UTP, shell elements were used with a mesh size of 2 mm. In ABH + DVAs, CBUSH elements were employed to simulate the DVA system’s behavior. The demonstration of the FEM simulation model can be seen in Fig. 2.

In the context of FEM simulations, the boundary conditions are carefully prescribed as follows: the four peripheral edges of the plate, which is embedded four ABHs, are constrained to remain fixed. Moreover, a unit harmonic excitation is imparted precisely at the centroid of the structure to induce dynamic responses within the system.

In addition, the numerical modeling methodology was extensively validated via a corresponding experimental analysis involving a plate with two integrated ABHs, as outlined in our previous research works29. For further elaboration on the experimental procedures and the details of the model validation, readers are encouraged to refer to the supplementary information appended to this manuscript.

Results and discussion

The focus position analysis in broadband for the thin-walled structure embedded with 4 ABH elements

In this section, a square steel plate with length of 408 mm equipped with four embedded ABH elements was utilized as seen in Fig. 1a. The parameters for ABH feature were defined as ε = 2.8 × 10–4, m = 2.2, with hmin = 1.0 mm, h0 = 8.0 mm and rABH = 100 mm. The four ABH elements were symmetrically distributed within the plate, with a 204 mm distance between their centers for each adjacent two ABH elements. All sides were clamped and a unit harmonic excitation was applied at the center of the plate. The material properties can be seen in Table 1.

To investigate the vibration reduction capabilities of thin-walled structures embedded with ABHs + DVAs across a broadband frequency range, it is essential to analyze the focusing behavior of ABHs within different frequency bands. Within the various frequency bands considered, the averaged acceleration contour is derived by calculating the root-mean-square (RMS) value of the acceleration amplitudes at each node for every frequency within the selected frequency band. This approach yields an average acceleration value at each node, which captures the overall vibrational behavior within the specified frequency range. In this study, a comparison has been made with a similar-quality UTP structure. Detailed model parameters are provided in “Design and numerical modeling of ABHs+DVAs plate” section. Under the influence of central point unit harmonic excitation and four-side fixed constraints, Fig. 3 illustrate the average acceleration response contour maps of the UTP and ABHs in different frequency bands: 0–500 Hz, 500 Hz–fcut (1103 Hz), and fcut (1103 Hz)–3k Hz. Notably, within the low frequency range of 0–500 Hz, there is no observable focusing performance in the ABHs, consistent with the behavior of the ABH element. However, in the frequency band of 500 Hz–fcut (1103 Hz), the vibration responses near the center of ABHs exhibit a concentration effect, while the vibration response of UTP is distributed evenly across nine equal areas. This suggests that the ABHs exhibits a significant vibration focusing property to some extent. Within the fcut (1103 Hz)–3000 Hz range, ABHs mostly concentrates the vibration responses into the dent of ABHs; however, the focusing point deviates from the ABHs center.

In summary, the ABHs exhibits exceptional vibration focusing characteristics across the broadband frequency range. This finding lays the foundation for future research on broadband vibration suppression in combination with DVA.

Low frequency broadband attenuation effect of ABHs + DVAs

When utilizing a DVA for vibration reduction, the device’s position has a significant impact on the structure’s vibration response. By positioning the DVA where the vibration response is the greatest, the attenuation amplitude can be maximized. In this research, the integration of ABHs and DVAs is utilized to analyze the effects of low-frequency, broadband vibration reduction. As a result, the design parameters of the DVAs are primarily based on the low-order resonance frequency, and the broadband vibration reduction effect is observed by adjusting the DVA’s location. Drawing from our exploration into the focusing properties of thin-walled structures equipped with ABHs in “The focus position analysis in broadband for the thin-walled structure embedded with 4 ABH elements” section, the frequency range between 0 and 4000 Hz is categorized into three distinct frequency bands: 0–500 Hz, 500–1103 Hz (cut-on frequency of the corresponding 4ABHs plate) and 1103–3000 Hz. The averaged acceleration contour for both UTP and 4ABHs plate are shown in Fig. 3.

-

1.

In the low-frequency band (0–500 Hz), demonstrates virtually no focusing effects for ABHs. The majority of the vibration response is concentrated in a circular region with the excitation point as the center. The point in the ABH’s dent with the maximum response is labeled as “a” and indicated in Fig. 4;

-

2.

As the frequency band progresses to the intermediate range (500 Hz–fcut), the structure embedded with ABHs displays initial signs of a focusing effect, which intensifies as the frequency rises, and the central feature defines the focusing position as “b”;

-

3.

In the high-frequency band (fcut–4000 Hz), the ABH structure’s focusing effect is prominent, and the focusing position is labeled as “c”.

According to multiple DVA parameter optimization methods31, the optimal parameter formula of the dynamic vibration absorber is obtained:

In this study, the parameters ξ, β, f, µ, n, and the locations of DVAs are considered. The damping ratio ξ, non-dimensional frequency band-width β, tuning frequency ratio f, mass ratio µ of the total mass of all DVAs to the mass of the thin-walled structure, and the number of DVAs n, with one DVA placed in each ABH indentation, are the key design parameters. The resonance frequencies in each band are: 402 Hz in the low-frequency band (0–500 Hz), no resonance frequency in the middle-frequency band (500 Hz–fcut), and 2950 Hz in the high-frequency band (fcut–4000 Hz). Four models are developed based on these parameters and DVAs attached positions. Table 2 presents the tuning frequencies and coupling positions of the models in question, while Fig. 4 illustrates the attachment positions of the DVAs. Specifically, for the case with µ = 0.1 and n = 4, the DVA parameters have been designed in accordance with the provided formulas. The detailed resulting data pertaining to these parameters is presented in Supplementary Table S1 of the supplementary information.

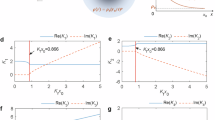

The comparison of acceleration frequency response before and after the installation of DVAs is presented in Fig. 5. When the DVAs parameters remain unchanged but their attached positions vary, Fig. 5a reveals that ABHs + DVAs-1 exhibits the most significant vibration amplitude attenuation effect at the first-order resonance frequency. This is primarily due to the DVAs in ABHs + DVAs-1 being positioned at the site with the maximum resonance response of the first order in ABHs, as anticipated. ABHs + DVAs-2 and ABHs + DVAs-3 produce a similar overall response level, featuring a relatively significant vibration attenuation effect across all frequencies.

When the DVA parameters differ but the attached positions remain unchanged, Fig. 5b demonstrates that ABHs + DVAs-4 exhibits a relatively significant vibration attenuation effect in the high-frequency range, exhibiting the best vibration attenuation near the design frequency (2950 Hz). Conversely, it lacks vibration attenuation in the low-frequency range.

Based on the above analysis, ABHs + DVAs-3 is chosen for comparison with other models, taking into account UTP, and ABHs + Damping (as described in “Numerical modeling” section) with hd = 2 mm and rd = 25 mm. The results of acceleration frequency response of each model are shown in Fig. 6. When compared to UTP, ABH exhibits a lower overall vibration response level. ABHs + Damping exhibits high damping effect at high frequency, except at 402 Hz. ABHs + DVAs-3 exhibits a significant attenuation of 31.4 dB at the formant peak of 402 Hz at low frequency and significant damping effect at high frequency.

To visualize the model’s average vibration response level across distinct frequency ranges, Table 3 and Fig. 7 presents the computed average acceleration amplitude within diverse frequency bands. A thorough analysis of the data summarized in Table 3 and the visual comparison presented in Fig. 7 reveals several significant observations:

-

1.

ABHs exhibit a lower vibration response compared to UTP of identical mass, indicating inherent vibration reduction properties.

-

2.

Within the 0–500 Hz frequency band, ABHs + DVAs-1, ABHs + DVAs-2, and ABHs + DVAs-3 all exhibit noteworthy vibration attenuation, despite having identical DVAs parameters across these three model groups but with distinct attached positions. Among these models, ABHs + DVAs-1 exhibits a vibration response approximately 9 dB lower than the other two models when the DVAs is located in the highest vibration response in this frequency band. However, the design parameters of ABHs + DVAs-4 target higher-order resonance frequencies, resulting in a lack of vibration attenuation within 0–500 Hz.

-

3.

Within the 500 Hz–fcut frequency range, the curves are smooth, indicating the absence of any resonance peaks, leading to minimal vibration attenuation.

-

4.

In the fcut–4000 Hz frequency band, ABHs + DVAs-4 exhibits the most notable vibration attenuation effect. This is primarily attributed to the DVA parameters being specifically tailored for resonance frequencies within this range. Additionally, ABHs + DVAs-2 and ABHs + DVAs-3 also exhibit significant vibration attenuation due to the attached position of DVAs at focusing positions within the 500 Hz–fcut and fcut–4000 Hz frequency bands respectively, with both focusing positions being in proximity to one another, where the damping in DVAs played a critical role in the vibration attenuation.

-

5.

Across the 0–4k Hz frequency range, models with DVAs positioned at focusing positions (including ABHs + DVAs-2, ABHs + DVAs-3, and ABHs + DVAs-4) all exhibit significant vibration attenuation effects. Specifically, the vibration level is reduced by approximately 17 dB when compared to ABHs alone.

-

6.

In the 0–8k Hz frequency band, ABHs + Damping and ABHs + DVAs-4 exhibit superior vibration attenuation levels, followed closely by ABHs + DVAs-3. It is worth noting that the mass of the damping layer accounts for only 0.23% of the thin-walled structure’s mass; however, it exerts a significant vibration attenuation effect in the high frequency range. ABHs + Damping could serve as a much effective lightweight solution for broadband vibration reduction, if low-frequency vibration reduction requirements are not considered.

To summarize, the preceding analysis highlights the critical role of DVA’s attached position and parameter design in vibration reduction across the entire frequency range. By positioning DVAs in the focusing area and specifying parameters with a low resonance frequency, it is possible to not only minimize the structure’s low-frequency vibration response but also enhance the overall vibration attenuation capabilities of DVAs.

Conclusions

This paper introduces and examines a thin-walled structure with embedded ABHs and distributed DVAs, designated as ABHs + DVAs, with the aim of enhancing vibration reduction efficiency across a broadband encompassing low frequencies. The key to achieving comprehensive frequency damping lies in effectively combining the effective damping effects of DVAs in the low frequencies with the focusing capabilities of ABHs in the mid-to-high frequencies.

The study conducts a numerical investigation of the focusing characteristics of ABHs and examines the impact of DVAs’ attached position on vibration reduction effects. The results indicate that the location of DVAs significantly impacts the broadband vibration reduction performance. By positioning DVAs near the focusing positions in the mid-to-high frequencies and optimizing parameters for a low resonance frequency, it is possible to achieve vibration attenuation not only in the low frequency range but also across the mid-to-high frequencies. This outcome relies on both the focusing capabilities of ABHs and the damping effects of DVAs placed in the focal region.

This study introduces a novel concept for achieving low frequency broadband vibration reduction in plate structures and represents a promising avenue for further optimization. However, practical implementation of DVAs remains an issue that requires attention. Future experimental research will aim to design corresponding DVA structures to bridge the theory and practice, paving the way for practical applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Garrido, H., Curadelli, O. & Ambrosini, D. Improvement of tuned mass damper by using rotational inertia through tuned viscous mass damper. Eng. Struct. 56, 2149–2153 (2013).

Krylov, V. V. Acoustic black holes: Recent developments in the theory and applications. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 61, 1296–1306 (2014).

Bowyer, E. P. & Krylov, V. V. Experimental study of sound radiation by plates containing circular indentations of power-law profile. Appl. Acoust. 88, 30–37 (2015).

Chong, B. M. P., Bin Tan, L., Lim, K. M. & Lee, H. P. A review on acoustic black-holes (ABH) and the experimental and numerical study of ABH-featured 3D printed beams. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 9, 1750078 (2017).

Zhao, C. & Prasad, M. G. Acoustic black holes in structural design for vibration and noise control. Acoustics 1, 220–251 (2019).

O’Boy, D. J., Krylov, V. V. & Kralovic, V. Damping of flexural vibrations in rectangular plates using the acoustic black hole effect. J. Sound Vib. 329, 4672–4688 (2010).

Li, H., Sécail-Géraud, M., Pelat, A., Gautier, F. & Touzé, C. Experimental evidence of energy transfer and vibration mitigation in a vibro-impact acoustic black hole. Appl. Acoust. 182, 108168 (2021).

Li, M., Deng, J., Zheng, L. & Xiang, S. Vibration mitigation via integrated acoustic black holes. Appl. Acoust. 198, 109001 (2022).

Kim, S.-Y. & Lee, D. Experimental investigation of a modular helix-acoustic black hole. Appl. Acoust. 214, 109661 (2023).

Du, X. & Fu, Q. Surrogate model-based multi-objective design optimization of vibration suppression effect of acoustic black holes and damping materials on a rectangular plate. Appl. Acoust. 217, 109837 (2024).

Xiaoyan, T., Guobao, F., Xudong, J. & Hetao, Z. Analytical model of high-frequency energy flow response for a beam with free layer damping. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 12(12), 1687814020984596 (2019).

Denis, V., Pelat, A., Gautier, F. & Elie, B. Modal overlap factor of a beam with an acoustic black hole termination. J. Sound Vib. 333, 2475–2488 (2014).

Conlon, S. C., Fahnline, J. B. & Semperlotti, F. Numerical analysis of the vibroacoustic properties of plates with embedded grids of acoustic black holes. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 137, 447 (2015).

Aklouche, O., Pelat, A., Maugeais, S. & Gautier, F. Scattering of flexural waves by a pit of quadratic profile inserted in an infinite thin plate. J. Sound Vib. 375, 38–52 (2016).

Denis, V., Pelat, A., Touze, C. & Gautier, F. Improvement of the acoustic black hole effect by using energy transfer due to geometric nonlinearity. Int. J. Non-linear Mech. 94, 134–145 (2017).

Li, H., Touze, C., Pelat, A., Gautier, F. & Kong, X. A vibro-impact acoustic black hole for passive damping of flexural beam vibrations. J. Sound Vib. 450, 28–46 (2019).

Zhao, L. Low-frequency vibration reduction using a sandwich plate with periodically embedded acoustic black holes. J. Sound Vib. 441, 165–171 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Low-frequency enhancement of acoustic black holes via negative stiffness. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 241, 107921 (2023).

Gao, N., Wei, Z., Zhang, R. & Hou, H. Low-frequency elastic wave attenuation in a composite acoustic black hole beam. Appl. Acoust. 154, 68–76 (2019).

Gao, N., Guo, X., Deng, J., Cheng, B. & Hou, H. Elastic wave modulation of double-leaf ABH beam embedded mass oscillator. Appl. Acoust. 173, 107694 (2021).

Gao, N., Wang, B., Lu, K. & Hou, H. Complex band structure and evanescent Bloch wave propagation of periodic nested acoustic black hole phononic structure. Appl. Acoust. 177, 107906 (2021).

Deng, J., Guasch, O., Maxit, L. & Gao, N. A metamaterial consisting of an acoustic black hole plate with local resonators for broadband vibration reduction. J. Sound Vib. 526, 116803 (2022).

Deng, J., Guasch, O., Maxit, L. & Gao, N. Sound radiation and non-negative intensity of a metaplate consisting of an acoustic black hole plus local resonators. Compos. Struct. 304, 116423 (2023).

Wan, Z., Zhu, X., Li, T. & Nie, R. Low-frequency multimode vibration suppression of an acoustic black hole beam by shunt damping. J. Vib. Acoust. Trans. ASME 144, 021012 (2022).

Wan, Z., Zhu, X., Li, T. & Fu, J. A method for improving wave suppression ability of acoustic black hole plate in low-frequency range. Thin-Walled Struct. 182, 110327 (2023).

Raybaud, G., Pelat, A., Ouisse, M. & Gautier, F. Zero reflections by a 1D acoustic black hole termination using thermally controlled damping. J. Sound Vib. 510, 116282 (2021).

Raybaud, G., Lee, J. Y., Jeon, W., Pelat, A. & Gautier, F. On the control of the absorption of an acoustic black hole by using attached point supports. J. Sound Vib. 548, 117562 (2023).

Yu, Y., Jia, X., Ouyang, H., Du, Y. & Peng, Y. Dynamic properties investigation of an acoustic black hole beam with dynamic vibration absorber based on analytical method. J. Sound Vib. 570, 118053 (2024).

Jia, X., Du, Y., Yu, Y. & Zhao, K. Vibration characteristics of plate structures embedded with acoustic black holes and distributed dynamic vibration absorbers. Int. J. Acoust. Vib. 24, 531 (2019).

Pelat, A., Gautier, F., Conlon, S. C. & Semperlotti, F. The acoustic black hole: A review of theory and applications. J. Sound Vib. 476, 115316 (2020).

Bandivadekar, T. & Jangid, R. Optimization of multiple tuned mass dampers for vibration control of system under external excitation. J. Vib. Control 19, 1854–1871 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52205169); National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4301301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J.: Methodology, software, writing—original draft; Y.Y.: Supervision, writing—review & editing; Y.D.: Conceptualization, validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Xx., Yu, Y. & Du, Y. Embedded periodically ABHs and distributed DVAs for passive low-frequency broadband vibration attenuation in thin-walled structures. Sci Rep 14, 18496 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69634-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69634-7