Abstract

Systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) has been proven to be associated with the prognosis of coronary artery disease and many other diseases. However, the relationship between SIRI and acute traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) has rarely been evaluated. The study aims to assess the prognostic value of SIRI for clinical outcomes in individuals with acute tSCI. A total of 190 patients admitted within eight hours after tSCI between January 2021 and April 2023 were enrolled in our study. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the association between SIRI and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grade at admission and discharge, as well as neurological improvement in tSCI patients, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the discriminative ability of SIRI in predicting AIS grade at discharge. After adjusting for confounding factors, SIRI positively correlated with the AIS grade (A to C) at admission and discharge, and negatively correlated with neurological improvement. The area under the curve values in ROC analysis was 0.725 (95% CI 0.647, 0.803). The study suggests that SIRI is significantly associated with an increased risk of poor clinical outcome at discharge in tSCI patients and has a certain discriminative value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) is increasingly recognized as a major cause of death and disability, causing serious psychological and economic burdens on patients. The prevalence of spinal cord injury (SCI) has increased rapidly from 236 to 1298 cases per million in the last three decades, and the annual global incidence is estimated to be as high as 2500–5000 individuals1. The estimated cumulative medical costs for patients with SCI range from $50,000 to $2 million2. Aside from the treatment of SCI itself, secondary costs including various complications (e.g., pressure ulcers, neuropathic pain, and deep vein thrombosis) and emergency admission are needed, which place an enormous burden on health systems and economies3.

Obtaining reliable indicators to predict the prognosis of patients with tSCI is widely acknowledged as crucial. Several recent studies have revealed that variety of indicators, such as blood cell counts and coagulation status, correlate with SCI’s clinical outcomes4,5. However, the prognostic value of these indicators in SCI remains limited. Thus, exploring other novel indicators related to the clinical outcome of SCI is justified. The pathophysiology of tSCI mainly includes two phases: primary injury is induced by instantaneous mechanical damage, while secondary injury refers to inflammation, which plays a crucial role in SCI6. Inflammation response is now considered to be a fundamental mechanism during the secondary phase of tSCI, which can induce metabolic and cellular dysfunction of neurons, significantly aggravating neurological dysfunction. Furthermore, sustained inflammation in the following weeks can precipitate additional cell death and exacerbate injury, thereby affecting functional recovery6. Therefore, inflammation-related biomarkers may provide enhanced predictive value for outcomes of tSCI patients7.

As previously mentioned, inflammatory response occurs within minutes after tSCI and involves astrocytes, T cells, microglia, and multiple other cell populations8. Studies have indicated that circulating neutrophils accumulate at the injury site within one hour of injury and are considered an important indicator of acute inflammation9,10. In addition, in the field of immunological investigation, the discriminative capacity of the systemic immune-inflammatory index (SII), alongside ratios such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), has been uncovered. These ratios are linked to peripheral blood counts and have shown relevance in gauging inflammatory reactions, cardiovascular conditions, malignancies, and respiratory ailments11,12.

Systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), another novel inflammatory indicator, is calculated in accordance with neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts. First reported by Qi et al.13 in 2016, SIRI has shown an ability to predict survival in adenocarcinomas patients. Moreover, SIRI has been shown to be associated with other conditions such as coronary artery disease (CAD) and adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction14,15. One study has also demonstrated SIRI’ utility in predicting complications before or after acute appendicitis surgery, suggesting it can serve as a predictive indicator for their occurrence16. Furthermore, several studies have validated that SIRI correlates with the severity of acute ischemic stroke and can function as a prognostic predictor17,18. However, the correlation between SIRI and tSCI has rarely been studied. Therefore, this study aims to assess the association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and the clinical outcomes of tSCI.

Methods

Study population

In this study, 310 participants admitted within eight hours after acute tSCI at the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University between January 2021 and April 2023 were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included: (1) participants aged < 18 years old; (2) initial Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) < 13; (3) individuals who had sustained traumatic injuries to anatomical areas aside from the spinal cord, characterized by an Abbreviated Injury Severity score of ≥ 3; (4) participants with admission AIS grade E; (5) participants with incomplete or missing data. Finally, 190 patients were included in this retrospective observational study to evaluate the effect size of SIRI-indicated inflammation on the clinical outcomes of tSCI (Fig. 1).

This study was conducted in accordance with the postulates of Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics boards of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (22SC-2023-191). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics boards of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University determined that informed consent was not necessary, and patient information was anonymized and de-identified prior to the analysis.

Anthropometric and laboratory data

In the observational study, clinical and demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and mechanism of injury) were obtained from medical history collection. Blood pressure (mmHg) was measured using mercury sphygmomanometers or electronic sphygmomanometers at admission. Blood sample was collected from each patient and analyzed within eight hours after tSCI. In addition, white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), lymphocyte count (LY), and monocyte count (MONO) were measured using the electrical impedance method. Hematological variables such as hemoglobin (HGB) levels were measured using the sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) hemoglobin method. In addition, the measurement of total protein (TP), total cholesterol (TC), serum creatinine (Scr) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were obtained professionally. For the etiology of SCI, “high fall” was defined as a fall from more than 1 meter19, while “stumble” was defined as W01 (i.e., fall on same level from slipping, tripping) and W18 (i.e., other slipping, tripping and falls) according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM)20. The SIRI index was calculated using the following formula: SIRI = neutrophil count × (monocyte count)/lymphocyte count21, whereas the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was calculated using the following formula: NLR = neutrophil count/lymphocyte count22.

Diagnostic criteria and outcome assessments

The diagnosis of tSCI was confirmed based on injury history, clinical manifestations, and radiological studies22. In the survey, we used the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) to evaluate the degree of impairment at their initial hospital admission (within the first three days) and discharge, and neurological improvement was defined as an improvement of at least one grade in AIS from discharge to admission. Additionally, we divided the outcome into poor (grade A to C) and good outcome (grade D to E) based on the AIS grade at discharge23.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) and compared with Student’s t-tests or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians along with their interquartile ranges and Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted for the statistical comparison. While categorical variables were expressed as a percentage of cases and were compared with χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. In this observational study, we used logistic models to assess the association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and the AIS grade at admission and discharge, as well as neurological improvement. Additionally, we performed a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate the predictive value of SIRI for the AIS grade at discharge.

Sensitivity analysis

In order to validate the robustness of association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and the AIS grade, two sensitivity analyses were performed. Sensitivity analysis one evaluated the association between the NLR, an inflammatory marker, and the AIS grade at admission and discharge, as well as neurological improvement after tSCI. Sensitivity analysis two further adjusted the HGB based on other confounders including age, sex, mean arterial pressure (MAP), spinal surgery, mechanism of injury, level of cord injury, and initial AIS grade.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants enrolled in the observational study

A total of 190 adult patients with tSCI were included in this study, 133 (70.00%) of whom were male. The mean age was 53 ± 13 years, and the median SIRI was 2.58 (interquartile range [IQR], 1.39–4.10), while the median NLR was 7.57 (IQR, 4.33–13.70). Among the participants included in the study, “stumble” was the leading cause of tSCI (41.58% of all included patients). “Blow to spine” was another major cause and accounted for 24.21% in tSCI patients. In addition, “high fall” accounted for 17.37%, “motor vehicle accident” accounted for 12.63%, and others 4.21%. For the level of cord injury, the cervical spinal cord had the largest proportion (77.89%), followed by lumbar (9.47%) and thoracic (7.89%), while “others”, defined as tSCI combining more than one site, occupied 4.74%. Of the 190 patients, 105 (55.26%) patients were classified as AIS grade A–C, and 85 (44.74%) as AIS grade D at admission.

In this observational study, 111 (58.42%) patients had good outcomes (AIS D to E), while 79 (41.58%) had poor outcomes (AIS A to C) at discharge. Males accounted for 78.48% of participants with poor outcomes and 63.96% with good outcomes. The mean age of the poor outcome group was 55 ± 13 years, and that of the good outcome group was 52 ± 13 years. In addition, the median ANC, NLR, and SIRI of patients in poor outcome group were 8.72 (IQR, 6.76–10.22) × 109/L, 11.80 (IQR, 6.30–17.94), and 3.87 (IQR, 2.24–6.93), respectively, which were higher than 6.96 (IQR, 5.14–9.04) × 109/L, 5.65 (IQR, 3.71–10.88), and 1.99 (IQR, 1.16–3.13) in patients with good outcomes at discharge. However, the mean MAP of poor outcome group was 88 ± 15 mmHg and lower than 97 ± 13 mmHg in the good outcome group. Additionally, the median LY level in poor outcome group was 0.76 (IQR, 0.52–1.09) × 109/L, which was lower than 1.23 (IQR, 0.78–1.60) × 109/L of the good outcome group, while the difference in monocyte levels between the two groups was not statistically significant.

Among the patients with poor prognosis at discharge, 67 (84.81%) patients received spinal surgery intervention. Additionally, tSCI occurred in the cervical in 58 (73.42%), thoracic in 11 (13.92%), lumbar in 5 (6.33%), and “others” in 5 (6.33%). In the good outcome group, 83 (74.77%) patients underwent spinal surgery. TSCI occurred in the cervical in 90 (81.08%), thoracic in 4 (3.60%), lumbar in 13 (11.71%), and “others” in 4 (3.60%) in participants with good outcomes. Above results were shown in Table 1.

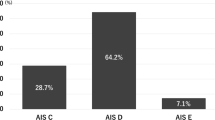

AIS grade conversion from hospital admission to final assessment

In the present study, the AIS grade was used to assess the degree of impairment in patients with tSCI. At admission, 40 patients were classified as AIS grade A (motor and sensory complete SCI), 24 as AIS grade B, 41 as AIS grade C and 85 as AIS grade D. At discharge, 29, 14, 36, 88, and 23 patients were classified as AIS grades A, B, C, D, and E, respectively.

Among the patients evaluated as having AIS grade A at admission, 5 patients improved to grade B, 3 patients improved to grade C, and 3 patients improved to grade D. Among the patients admitted with AIS grade B, 10 patients improved to grade C, 4 patients improved to grade D, 1 patient improved to grade E. In 41 patients diagnosed with AIS grade C at admission, 18 patients improved to grade D. In addition, 22 patients with an initial AIS grade D improved to grade E. Finally, 66 patients showed neurological improvement from hospital admission to the final assessment. The results about AIS classification conversion were shown in Table 2.

Association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and AIS grade at admission and discharge, as well as neurological improvement in the participants with tSCI

To explore the associations between SIRI and AIS grade at admission and discharge, as well as neurological improvement, logistic regression analyses were performed. In the logistic regression analyses without adjustment for confounders, when SIRI increased by 1 unit, the risk of AIS grade (A to C) at admission and discharge increased by 42.6% (odds ratio [OR] 1.426, 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.214, 1.673, P < 0.0001) and 50.1% (OR: 1.501, 95% CI: 1.283, 1.755, P < 0.0001), respectively, while the OR of SIRI on neurological improvement was 0.907 (95% CI: 0.813, 1.012, P = 0.080) (Model 1). In Model 2, after adjusting for age and sex, the associations between SIRI and the AIS grade (A to C) at admission and discharge remained statistically significant with the ORs of 1.403 (95% CI: 1.192, 1.650, P < 0.0001) and 1.492 (95% CI: 1.273, 1.749, P < 0.0001), indicating that for each unit increase in the SIRI, the risk of grade (A to C) at admission and discharge increased 40.3% and 49.2%. In Model 3, after further adjusting for MAP, spinal surgery, mechanism of injury, level of cord injury, and initial AIS grade (spinal surgery and initial AIS grade only were adjusted in AIS grade at discharge and neurological improvement analyses) based on Model 2, if SIRI increased by 1, the risk of AIS grade (A to C) at admission and discharge increased by 41.8% (OR: 1.418, 95% CI: 1.190, 1.689, P < 0.0001) and 35.2% (OR: 1.352, 95% CI: 1.070, 1.709, P = 0.012), while the odds of neurological improvement decrease by 16.7% (OR: 0.833, 95% CI: 0.728, 0.952, P = 0.007). The results were seen in Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity test 1, we investigated the association between NLR-indicated inflammation and AIS grade at admission and discharge in patients with acute tSCI. Similar to SIRI, after adjusting for age, sex, MAP, spinal surgery, mechanism of injury, level of cord injury, initial AIS grade (spinal surgery and initial AIS grade only were adjusted in AIS grade at discharge and neurological improvement analyses), for each unit increased in NLR, the risk of AIS grade A–C at admission and discharge increased by 19.1% (OR: 1.191, 95% CI: 1.105, 1.283, P < 0.0001) and 12.9% (OR: 1.129, 95% CI: 1.011, 1.261, P = 0.032), respectively, in Model 3. In addition, the sensitivity analyses showed a similar trend between NLR and neurological improvement with an OR of 0.897 (95% CI: 0.837, 0.962, P = 0.002), indicating that for every 1 unit increased in NLR, the odds of neurological improvement decreased by 10.3%. Above results were presented in Table 4. In the sensitivity test 2, we further adjusted for HGB based on the adjusted confounders in Model 3, when SIRI level increased by 1 unit, the risk of AIS grade A–C at admission and discharge increased by 41.4% (OR: 1.414, 95% CI: 1.182, 1.691, P < 0.0001) and 37.1% (OR: 1.371%, 95% CI: 1.077, 1.745, P = 0.01), while the odds of neurological improvement decreased by 16.4% (OR: 0.836, 95% CI: 0.730, 0.957, P = 0.01) (see Supplementary Table S1 online).

Receiver operating characteristic analysis

In this study, we performed the ROC analysis to evaluate the discriminatory power of SIRI for the outcomes at discharge of patients with tSCI (Fig. 2A–C). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.725 (95% CI: 0.647, 0.803) for SIRI, and a value of 3.247 predicted the poor clinical outcomes at discharge in tSCI patients well, with a sensitivity of 60.8% and a specificity of 78.4% (positive predictive value [PPV]: 66.7% and negative predictive value [NPV]: 73.7%). Additionally, the AUC of SIRI with the adjustment of age, sex (Model 2) was 0.762 (95% CI: 0.690, 0.834) with a sensitivity of 65.8% and a specificity of 71.2% (PPV: 61.9% and NPV: 74.5%), while after adjusting for all confounding factor (Model 3), the AUC was 0.966 (95% CI: 0.943, 0.990) with a sensitivity of 98.7% and a specificity of 84.7% (PPV: 82.1% and NPV: 98.9%). The results were seen in Table 5.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis. (A) The graph indicates the discriminatory value of SIRI for poor outcomes (grade A to C) at discharge in tSCI patients (Model 1). (B) The ROC of SIRI with adjustment for age and sex (Model 2). (C) The ROC of SIRI with adjustment for all confounding factor (Model 3). (ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive rate).

Furthermore, we assessed the discriminatory ability of NLR and each individual variable within the SIRI score for the outcomes at discharge of with tSCI patients. The results showed that the AUCs of NLR, ANC, MONO and LY were 0.730 (95% CI 0.658, 0.801), 0.640 (95% CI 0.561, 0.719), 0.519 (95% CI 0.434, 0.604) and 0.711 (95% CI 0.637, 0.784), respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online).

Discussion

This is the first observational study to provide evidence showing the association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and an increased risk of poor clinical outcome at discharge in patients with tSCI. In the observational study of 190 participants, we observed that the SIRI-indicated inflammation was significantly associated with an increased risk of AIS grade (A to C) at admission and discharge, and was inversely correlated with neurological improvement, independent of conventional confounding factors. In addition, the area under the curve (> 0.7) of the ROC analysis showed that SIRI-indicated inflammation had a good discriminative value for outcome at discharge in patients with tSCI. This study suggests that SIRI contributes to an increased risk of poor outcome and is a promising predictor of clinical prognosis in patients with acute tSCI.

SCI represents a main cause of death and disability, and its incidence and prevalence remain high24. Research has shown that the main causes of SCI are traffic accidents, falls, work accidents, gunshot wounds, violent crime, and sports accidents25. Depending on the anatomical level and severity of the injured spinal cord, patients with SCI may present with neurological impairment, sensory loss, intestinal and bladder dysfunction, and even death. Inflammation, the fundamental pathogenesis in the second stage, plays an important role in the mechanism of SCI. Several studies have revealed that SCI can directly lead to necrosis and apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells, resulting in the destruction of the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB), leakage of vascular substances, and accumulation of various inflammatory cytokines that cause inflammation26,27. In addition, one study shows that inflammatory reactions occur within minutes after injury and can last from days to years28. Currently, several inflammatory markers such as NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII have been used to assess the correlation between inflammation and prognosis in central nervous system (CNS) diseases, hepatocellular carcinoma, acute myocardial infarction, and tumors29,30. Additionally, a study conducted by Zhou et al.22 revealed that NLR, PLR, and SII could be used as suitable verification indices of inflammation for assessing the severity and prognosis in patients with tSCI, and NLR had a higher diagnostic performance than PLR and SII. However, the predictive value of these inflammatory markers for SCI remains limited even many predictive models have been built, and it is necessary to explore new inflammatory markers for prognostic evaluation.

SIRI, an economical indicator of inflammation, has been confirmed to be associated with various diseases and has a certain predictive value. A study conducted by Chao et al.21 confirmed that although SIRI, NLR, PLR, and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio (MLR) were correlated with cervical cancer prognosis, only SIRI was an independent prognostic factor for the disease, showing a higher predictive value. A recent study conducted in China suggested that SIRI exhibited a significant correlation with an escalated mortality risk among patients with stroke after adjusting for conventional confounding factors, and had a higher diagnostic value with a significantly greater area under the curve than PLR, NLR, LMR ratio and red blood cell distribution width (RDW)18. In addition, several studies have demonstrated that SIRI can be used to evaluate the activity of rheumatoid arthritis, development of stroke-associated pneumonia, and recurrence after radiofrequency ablation in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma31,32,33.

Consistent with the above results, the present study concludes that SIRI-indicated inflammation is significantly associated with an increased risk of poor clinical outcome at discharge in patients with tSCI after adjusting for conventional confounding factors. The formula for SIRI calculation shows that the change in SIRI depends on the changes in neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts. Hsu et al.34 found that neutrophils migrated to injured areas after tSCI, resulting in the release of chemokines and aseptic inflammation when the BSCB was disrupted. Indeed, neutrophils make up 50–70% of the total white blood cells and are the first cells to gather towards the damaged area; they can accumulate within a few hours and peak within 6–12 h35. Additionally, activated neutrophils can aggravate oxidative stress and further increase damage, leading to CNS dysfunction36. Different from the trend of neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes may decrease first and then increase in the acute phase after SCI. A study conducted by Riegger et al.2 showed that the numbers of CD14 monocytes, CD3 T-lymphocytes, CD19 B-lymphocytes, and molecular histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II cells rapidly decreased within 24 h after tSCI. In addition, monocyte and lymphocyte-derived cytokines are released in the late stages of neutrophil inflammation and peak seven days after injury37. At the beginning of acute SCI, neutrophil counts increase more rapidly than other WBC counts, but an increase in lymphocyte counts is usually seen in chronic inflammation or viral infection, indicating that the lymphocyte count does not increase significantly after tSCI38. Therefore, SIRI increases significantly during the early stages of acute SCI. Our study observed significantly higher absolute neutrophil counts and lower lymphocyte counts in patients with poor prognoses. Nevertheless, the monocyte count in patients with poor SCI prognosis of spinal cord injury was lower, but the difference was not statistically significant. Ultimately, patients with a higher SIRI at admission had an increased risk of AIS grade A to C, which showed that the higher the SIRI at admission, the more severe the SCI.

In addition, our study demonstrated that SIRI positively correlated with poor outcome at discharge and inversely correlated with neurological improvement. The potential mechanism may be that spinal cord injury can induce damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP), then DAMP initially triggers an inflammatory response which worsens inflammation-related SCI39. Moreover, after tSCI, neutrophils and leukocytes rapidly accumulate in the injured spinal cord, resulting in the destruction and injury of surviving nerve tissue cells40. Additionally, the research conducted by Feng et al.41 suggested that infiltrated neutrophils promoted neuroinflammation and disrupted the BSCB by producing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which subsequently leaded to the aggravation of spinal cord edema and neuronal apoptosis. Finally, the higher the degree of inflammation indicated by SIRI, the worse the prognosis at discharge. Several studies have reported similar trends, showing that secondary inflammation increases the risk of poor prognosis in patients with CNS injuries6,42.

Of note, one recent study conducted to explore the predictive value of SII and SIRI for tSCI demonstrated a similar negative trend for the SIRI effect on AIS grade conversion, defined as an improved AIS grade (≥ 1 AIS grade improvement) at discharge. However, the association was non-significant with an OR of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.01, P = 0.125) after adjusting for confounding factors43. The inconsistency of SIRI effect on AIS grade conversion in patients with tSCI may involve several factors. First, the heterogeneity (e.g., age, sex, etiology, AIS grade at admission, and level of cord injury) of the two populations included may contribute to the difference in SIRI's effect. Second, the difference in peripheral blood samples drawing time (8 h vs 24 h after admission) between the two studies may be one of the important reasons for the difference in SIRI's effect. As mentioned earlier, neutrophils rise rapidly within hours after tSCI and peak within 6–12 h35, while peripheral blood extraction within 24 h after admission may result in lower levels of neutrophils because they have already passed their peak. In addition, the difference in blood drawing time will also lead to inconsistent changes in monocytes and lymphocytes, which may eventually result in the heterogeneity of SIRI’s effect. Finally, the inconsistency in instruments and techniques used to measure neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes may also lead to differences in the above cell values, ultimately affecting the effect of SIRI.

In summary, the findings reveal that SIRI is highly related to injury severity and neurological prognosis and can be used as a reliable indicator of inflammation, and increasing SIRI increases the risk of poor outcome in patients with tSCI. Additionally, the ROC analysis performed in the study shows that the area under the curve is > 0.7. These findings suggest that SIRI has a certain prognostic value for poor outcome at discharge in patients with tSCI.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study is observational and enrolls a small sample size, which may led to a selection bias. Second, some information, such as smoking history and drinking status, is lacking, but they may be important for the outcome. Third, although we had adjusted for MAP levels at admission when exploring the relationship between SIRI and outcomes, this study lacks details of blood pressure management, particularly during spinal surgery, which may affect SIRI's effect. Additionally, the information on whether complications such as infection or deep vein thrombosis occurred is lacking in our study. Fourth, we only analyzed the relationship between SIRI and AIS grade at discharge in patients with tSCI, further studies were warranted to explore the relationship between SIRI and long-term follow-up. Finally, the peripheral blood samples drawing time affects SIRI’s value, which in turn may affect SIRI’s effect in predicting the outcome in tSCI patients. Therefore, to predict tSCI outcome by SIRI, the blood sample should be drawn at an early time after admission. Despite these limitations, the present study analyzes the association between SIRI-indicated inflammation and outcomes at discharge in tSCI patients and provides evidence to better elucidate the complicated relationship between inflammation and motor recovery in individuals with tSCI.

Conclusions

In summary, SIRI-indicated inflammation is significantly associated with an increased risk of poor clinical outcomes at discharge in patients with tSCI. Measuring SIRI at admission helps assess the clinical outcomes of patients with tSCI, and early anti-inflammatory treatment to reduce SIRI may significantly improve prognosis.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chay, W. & Kirshblum, S. Predicting outcomes after spinal cord injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 31, 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2020.03.003 (2020).

Riegger, T. et al. Immune depression syndrome following human spinal cord injury (SCI): A pilot study. Neuroscience 158, 1194–1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.021 (2009).

Ding, L. et al. Expression of long non-coding RNAs in complete transection spinal cord injury: A transcriptomic analysis. Neural Regen. Res. 15, 1560–1567. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.274348 (2020).

Qiu, Z. et al. Clinical predictors of neurological outcome within 72 h after traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 6, 38909. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38909 (2016).

Yuan, F. et al. Predicting outcomes after traumatic brain injury: The development and validation of prognostic models based on admission characteristics. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 73, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31824b00ac (2012).

Faden, A. I., Wu, J., Stoica, B. A. & Loane, D. J. Progressive inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration after traumatic brain or spinal cord injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 681–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13179 (2016).

Orr, M. B. & Gensel, J. C. Spinal cord injury scarring and inflammation: Therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics 15, 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0631-6 (2018).

Donnelly, D. J. & Popovich, P. G. Inflammation and its role in neuroprotection, axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 209, 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.009 (2008).

Neirinckx, V. et al. Neutrophil contribution to spinal cord injury and repair. J. Neuroinflam. 11, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-014-0150-2 (2014).

Freyermuth-Trujillo, X., Segura-Uribe, J. J., Salgado-Ceballos, H., Orozco-Barrios, C. E. & Coyoy-Salgado, A. Inflammation: A target for treatment in spinal cord injury. Cells 11, 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11172692 (2022).

Nost, T. H. et al. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36, 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00752-6 (2021).

Larmann, J. et al. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio are associated with major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in coronary heart disease patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01500-6 (2020).

Qi, Q. et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer 122, 2158–2167. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30057 (2016).

Dziedzic, E. A. et al. Investigation of the associations of novel inflammatory biomarkers-systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI)-with the severity of coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome occurrence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23179553 (2022).

Chen, Y., Jin, M., Shao, Y. & Xu, G. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: A propensity score-matched analysis. Dis. Mark. 2019, 4659048. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4659048 (2019).

Cakcak, I. E., Turkyilmaz, Z. & Demirel, T. Relationship between SIRI, SII values, and Alvarado score with complications of acute appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ulus Travma Acil. Cerrah. Derg. 28, 751–755. https://doi.org/10.14744/tjtes.2021.94580 (2022).

Ma, F. et al. The relationship between systemic inflammation index, systemic immune-inflammatory index, and inflammatory prognostic index and 90-day outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. J. Neuroinflam. 20, 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02890-y (2023).

Zhang, Y., Xing, Z., Zhou, K. & Jiang, S. The predictive role of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in the prognosis of stroke patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 16, 1997–2007. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S339221 (2021).

Zhang, Z. R., Wu, Y., Wang, F. Y. & Wang, W. J. Traumatic spinal cord injury caused by low falls and high falls: A comparative study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16, 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02379-5 (2021).

Chen, Y., Tang, Y., Allen, V. & DeVivo, M. J. Fall-induced spinal cord injury: External causes and implications for prevention. J. Spinal Cord Med. 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772315Y.0000000007 (2016).

Chao, B., Ju, X., Zhang, L., Xu, X. & Zhao, Y. A novel prognostic marker systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for operable cervical cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 10, 766. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00766 (2020).

Zhou, W. et al. Diagnostic and predictive value of novel inflammatory markers of the severity of acute traumatic spinal cord injury: A retrospective study. World Neurosurg. 171, e349–e354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.12.015 (2023).

Geisler, F. H., Coleman, W. P., Grieco, G., Poonian, D. & Sygen Study, G. The Sygen multicenter acute spinal cord injury study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, S87-98. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200112151-00015 (2001).

Ding, W. et al. Spinal cord injury: The global incidence, prevalence, and disability from the global burden of disease study 2019. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 47, 1532–1540. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000004417 (2022).

Quadri, S. A. et al. Recent update on basic mechanisms of spinal cord injury. Neurosurg. Rev. 43, 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-1008-3 (2020).

Aube, B. et al. Neutrophils mediate blood-spinal cord barrier disruption in demyelinating neuroinflammatory diseases. J. Immunol. 193, 2438–2454. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1400401 (2014).

Xun, C. et al. Tocotrienol alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress in a rat model of spinal cord injury via suppression of transforming growth factor-beta. Exp. Ther. Med. 14, 431–438. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.4505 (2017).

Bloom, O., Herman, P. E. & Spungen, A. M. Systemic inflammation in traumatic spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 325, 113143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113143 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. The correlation between PLR-NLR and prognosis in acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Transl. Res. 13, 4892–4899 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Association of dietary inflammatory potential with blood inflammation: The prospective markers on mild cognitive impairment. Nutrients 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122417 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) as a novel biomarker in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A multi-center retrospective study. Clin. Rheumatol. 41, 1989–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06122-1 (2022).

Wang, R. H. et al. The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Immunol. 14, 1115031. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1115031 (2023).

Xin, Y. et al. A systemic inflammation response index (SIRI)-based nomogram for predicting the recurrence of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 45, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-021-02965-4 (2022).

Hsu, L. C. et al. IL-1beta-driven neutrophilia preserves antibacterial defense in the absence of the kinase IKKbeta. Nat. Immunol. 12, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.1976 (2011).

Han, Y., Zhao, R. & Xu, F. Neutrophil-based delivery systems for nanotherapeutics. Small 14, e1801674. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201801674 (2018).

Tei, R., Kaido, T., Nakase, H. & Sakaki, T. Protective effect of C1 esterase inhibitor on acute traumatic spinal cord injury in the rat. Neurol. Res. 30, 761–767. https://doi.org/10.1179/174313208X284241 (2008).

Beck, K. D. et al. Quantitative analysis of cellular inflammation after traumatic spinal cord injury: Evidence for a multiphasic inflammatory response in the acute to chronic environment. Brain 133, 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp322 (2010).

Zhao, J. L. et al. Circulating neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio at admission predicts the long-term outcome in acute traumatic cervical spinal cord injury patients. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21, 548. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03556-z (2020).

Helmy, A., De Simoni, M. G., Guilfoyle, M. R., Carpenter, K. L. & Hutchinson, P. J. Cytokines and innate inflammation in the pathogenesis of human traumatic brain injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.09.003 (2011).

Shlosberg, D., Benifla, M., Kaufer, D. & Friedman, A. Blood-brain barrier breakdown as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2010.74 (2010).

Feng, Z. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps exacerbate secondary injury via promoting neuroinflammation and blood-spinal cord barrier disruption in spinal cord injury. Front. Immunol. 12, 698249. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.698249 (2021).

Kinoshita, K. Traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology for neurocritical care. J. Intensive Care 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-016-0138-3 (2016).

Wang, C. et al. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. Eur. Spine J. 33, 1245–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-08114-4 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (GJJ2201442). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.Y. designed this project, edited the manuscript, and supervised the 31 study. M.Z. extracted and compiled the data, and wrote the manuscript. Z.H.D., L.Y. conducted data analyses and assisted the data interpretation. Z.F.M. and M.L.Z. assisted the data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, M., Deng, Z., Yuan, L. et al. Association of systemic inflammatory response index and clinical outcome in acute traumatic spinal cord injury patients. Sci Rep 14, 19085 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69699-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69699-4