Abstract

This study aimed to find a safe and effective cumulative cisplatin dose (CCD) for concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) beneficiaries among elderly nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients. A total of 765 elderly (≥ 60 years old) NPC patients treated with cisplatin-based CCRT and IMRT-alone from 2007 to 2018 were included in this study. RPA-generated risk stratification was used to identify CCRT beneficiaries. CCDs were divided into CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 and their OS and nephrotoxicity compared. Pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA and clinical stage were incorporated into the RPA model to perform risk stratification. All patients were classified into either a high-risk group (n = 158, Stage IV), an intermediate-risk group (n = 193, EBV DNA > 2000 copy/mL & Stage I, II, III) or a low-risk group (n = 414, EBV DNA ≤ 2000 copy/mL & Stage I, II, III). The 5 year OS of CCRT vs. IMRT alone in the high-, intermediate- and low-risk groups after balancing covariate bias were 60.1 vs 46.6% (p = 0.02), 77.8 vs 64.6% (p = 0.03) and 86.2 vs 85.0% (p = 0.81), respectively. The 5 year OS of patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 after balancing covariate bias in the high-risk group were 45.2, 48.9, 73.4 and 58.3% (p = 0.029), in the intermediate-risk group they were 64.6, 65.2, 76.8 and 83.6% (p = 0.038), and in the low-risk group they were 85.0, 68.1, 84.8 and 94.0% (p = 0.029), respectively. In the low-risk group, the 5 year OS of Stage III patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 were 83.5, 76.9, 85.5 and 95.5% (p = 0.044), respectively. No Grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity occurred. Therefore, in our study, Stage I, II, & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml and Stage III, IV elderly NPC patients may be CCRT beneficiaries. 80 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 is recommended for the high-risk (Stage IV) group, and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 for the intermediate-risk (Stage I, II, III & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml) and low-risk (Stage III & EBV DNA ≤ 2000 copy/ml) groups. No grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity occurred in any of the CCD groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a head and neck cancer prevalent in southern China1. Several phase III clinical trials and meta-analyses have confirmed that concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) could improve the overall survival (OS) of locally advanced NPC patients2,3,4,5. At present, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend CCRT for Stage II–IVA NPC6. However, Liu H et al. found that CCRT in elderly NPC patients did not significantly improve the 5 year OS (43.6 vs. 27.3%, p = 0.893) or disease-specific survival (DSS) (43.6 vs. 34.1%, p = 0.971) compared with RT alone7. Furthermore, a recent retrospective trial including 247 elderly NPC patients also showed no significantly different locoregional relapse-free survival (LRRFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), DSS or OS benefits between CCRT and IMRT alone (all p > 0.05)8. This raises the question as to whether all elderly NPC patients may benefit from current CCRT strategies9. And given the general increase in life expectancy, elderly NPC patients warrant more attention7,10.

Previous studies have shown that > 5 weekly cycles of 40 mg/m2 or a CCD of 200 mg/m2 might be a prognostic factor for elderly NPC patients11,12,. However, toxicity is an issue when administering a high dose of cisplatin, which is drug specific and has dose-limiting adverse effects13,14. As such, compliance with the regimen in the NPC-0099 trial was only about 60–70%3. Relatedly, Ngamphaiboon N et al. reported that 26.4% of locally advanced NPC patients who received CCRT experienced cisplatin-related nephrotoxicity and had a significantly shorter OS11. Adjunct to that, elderly patients with comorbidities, poorer performance status, less social support and reduced organ function may be unable to tolerate CCRT15. For example, population-based studies have shown that impaired kidney function is common among the elderly, with a 15% prevalence in those 70 years and older16. Therefore, the prognosis of CCRT in elderly NPC patients is inconsistent and requires further platinum dose studies and nephrotoxicity analyses in order to weigh up the risks and benefits. To overcome this problem, we explored the prognosis of elderly NPC patients receiving CCRT with different CCDs and assessed nephrotoxicity in order to find a safe and effective dose.

Materials and methods

Patient population

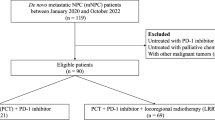

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (SL-B2022-372-01) of Sun Yat-sen University cancer center (SYSUCC) and the requirement for informed consent was waived. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We reviewed the NPC-specific dataset using a well-established big-data platform (Yi-du Cloud Technology Ltd., Beijing, China)17. The inclusion criteria were: initially diagnosed with non-distant metastasis NPC; ≥ 60 years old; received single-agent cisplatin-based CCRT and IMRT alone; a detailed medical history; and complete basic laboratory tests. The exclusion criteria were: concurrent presence of a second primary tumor; receipt of induction chemotherapy or targeted therapy; incomplete medical records or loss to follow-up. A total of 765 patients between June 2007 and January 2018 were included.

Diagnosis and treatment

All patients underwent pre-treatment evaluation, including chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT), nasopharynx and neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy, hematological and biochemical tests, and a physical examination. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) and CT (PET-CT) or whole-body bone scanning (ECT) was used to determine the TNM Stage. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain-reaction (PCR) assay was used to test the pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA titer for each patient.

All patients were restaged according to the 8th edition of the American joint committee on cancer/union for international cancer control (AJCC/UICC) manual. The target volume delineation details and IMRT plans were in line with previous studies conducted at SYSUCC18,19, and are summarized in the Supplementary Material. For patients who received CCRT, cisplatin was given weekly (40 mg/m2), or in weeks 1, 4, and 7 (80 or 100 mg/m2) during IMRT.

Assessment 27

Assessment 27 (ACE-27)20 is a comorbidity and health severity scoring system that includes 27 different organs and systems of the body. ACE-27 scores were calculated from patients’ medical records and classified as none (score 0), mild (score 1), moderate (score 2), or severe (score 3–4).

Nephrotoxicity

Nephrotoxicity was defined using creatinine (Cr) values via routine biochemical tests after each course of chemotherapy according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), Version 5 (CTCAE Files (nih.gov), and classified as: Grade 1, 1.0 to 1.5 times the upper limit of the normal value (ULN); Grade 2, 1.5 to 3.0 times the ULN; Grade 3, 3.0 to 6.0 times the ULN; or Grade 4, 6.0 times the ULN or greater.

Follow-up and endpoint

Patients were reviewed every 3 months during the first two years and every 6 months during the next three years, and then annually thereafter. Complete clinical examinations, fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy and plasma EBV DNA were routinely performed during the visit. MRI, abdominal ultrasound, contrast imaging, ECT/PET-CT, and cytological biopsy were recommended for patients with clinically suspected metastases. The primary endpoint was OS, which was defined as the time from the initial treatment until the date of death from any cause, or the last follow-up date.

Statistical analysis

All analysis were performed using R (http://www.r-project.org/). Continuous variables were converted into categorical variables according to established clinical cut-off points (albumin [ALB] and C-reactive protein [CRP]). Hemoglobin (HGB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were classified as normal or abnormal according to established clinical cut-off points. Pre-treatment EBV DNA was converted into a categorical variable according to the optimal cut-off value (2000 copy/ml), as confirmed by prior studies21,22. X-tile software was used to calculate the optimal grouping cut-off points for people who received single-agent cisplatin-based CCRT: 75 and 180 mg/m2 were the two cut-off points (Supplementary Figure S1). According to the clinical medication, the patient’s doses were divided into: CCD = 0 (IMRT alone), 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160, and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression was used to estimate the effect of the variables on OS. Statistically significant predictors for 5 year OS in the multivariate Cox regression were included in the RPA analysis using R to stratify patients into risk groups with significantly different prognoses. Excessive branches of the RPA-generated risk stratification were removed using the prune function for realistic clinical application. The survival of the patients treated with CCRT or IMRT alone in each risk group was compared to investigate the chemotherapy beneficiaries. The probability of nephrotoxicity in all populations was compared using trend chi square. To account for selection bias, observed differences in baseline characteristics between patients who received different CCDs were controlled for using a weighted propensity score analysis. The propensity of four different dose intervals was estimated from a logistic regression model that included all the available covariates. The inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)23 was used to adjust for covariable imbalances. OS was calculated using the IPT-weighted Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the stratified log-rank tests. All p values were two-tailed; and a p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

This retrospective study was approved by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (IRB-approved number, SL-B2021-474-02).

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 119.22 (1.37–151.6) months. The median age was 66 (60–85) years old, and the male to female ratio was 2.75 (561/204). Overall, 354 (46.3%) patients received CCRT and 411 (53.7%) patients received IMRT alone. The median CCD for patients receiving CCRT was 160 (0–300) mg/m2. Of the patients receiving CCRT, 45 (12.7%) received 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 174 (49.2%) received 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 135 (38.1%) 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2. The patient characteristics for the CCD groups are summarized in (Table 1).

In total, 55/765 (7.2%) patients developed locoregional failure, 89/765 (11.6%) patients developed distant metastases and 213/765 (27.8%) patients died (133 patients because of the tumor). The 5 year OS, DSS, DMFS, and LRFS were 76.3, 83.0, 84.1, 88.0, and 92.9%. The 5 year OS rate of patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 were 75.4, 66.3, 79.6 and 78.2% (p = 0.197), respectively (Supplementary Figure S2).

RPA-generated risk stratification and the identification of CCRT beneficiaries

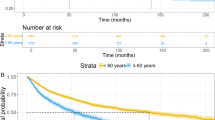

The IMRT alone dataset (n = 411) was used for the explorative construction of RPA models for generating risk stratification. The predictive modeling approach, conditional inference trees24, was used to evaluate all the baseline variables (age, gender, smoking, drinking, ACE-27, WHO category, T stage, N stage, clinical Stage, pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA, HGB, ALB, LDH, and CRP). Pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA and clinical Stage were verified to have significant effects on OS and were incorporated into the RPA model to perform risk stratification. All patients were classified into one of three groups: a high-risk group (n = 158, Stage IV), an intermediate-risk group (n = 193, pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA > 2000 copy/mL & Stage I, II, III) or a low-risk group (n = 414, pre-treatment plasma EBV DNA ≤ 2000 copy/mL & Stage I, II, III) (Fig. 1A). The baseline characteristics of the 765 patients in the different risk groups are summarized in (Supplementary Table 1). The 5 year OS rate of the whole cohort was 86.5, 71.6 and 54.7% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 1B). The OS curves of patients in different risk groups receiving CCRT and IMRT were shown in (Fig. 2A–C). The 5 year OS of the CCRT group vs. the IMRT alone group in the high-, mid- and low-risk groups were 60.1 vs 46.6% (p = 0.02), 77.8 vs 64.6% (p = 0.03) and 86.2 vs 85.0% (p = 0.81), respectively (Fig. 2D–F) after balancing the covariate bias.

Analysis of the prognostic implications of the CCDs among the three risk groups

Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to the different CCD groups in the high-, mid- and low-risk groups are shown in (Fig. 3), and the covariate balance of the adjusted baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in (Supplementary Fig. 3). The 5 year OS of patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 in the high-risk group were 46.4, 50.9, 71.1 and 51.5% (p = 0.097), respectively (Fig. 3A). After adjustment for the covariable imbalance, they were 45.2, 48.9, 73.4 and 58.3% (p = 0.029), respectively (Fig. 3D). In the intermediate-risk group they were 68.5, 61.5, 78.5, and 75.4% (p = 0.3) (Fig. 3B), respectively. After adjustment for the covariable imbalance, they were 64.6, 65.2, 76.8 and 83.6% (p = 0.038), respectively (Fig. 3E). In the low-risk group they were 85.5, 80, 84.8 and 93.8%, respectively (p = 0.22) (Fig. 3C). After adjustment for the covariable imbalance, they were 85.0, 68.1, 84.8 and 94.0% (p = 0.029), respectively (Fig. 3F).

Figure 4 shows a forest plot of the prognostic value of the categorized CCDs for the cohort before (Fig. 4A) and after (Fig. 4B) weighting. In the high-risk group, compared with CCD = 0 mg/m2, the death hazard ratios for 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 after weighting were 1.00 (95% CI 0.39–2.57) (p = 0.996), 0.46 (95% CI 0.26–0.82) (p = 0.008) and 0.48 (95% CI 0.24–0.96) (p = 0.037), respectively. In the intermediate-risk group after weighting, they were 0.96 (95% CI 0.35–2.61) (p = 0.932), 0.65 (95% CI 0.34–1.24) (p = 0.191) and 0.31 (95% CI 0.13–0.75) (p = 0.010), respectively. And in the low-risk group, they were 1.81 (95% CI 0.61–5.34) (p = 0.281), 1.22 (95% CI 0.70–2.14) (p = 0.485) and 0.39 (95% CI 0.16–0.94) (p = 0.037), respectively.

Subgroup analysis of the prognostic implications of the CCDs in the low-risk group

The baseline characteristics of the different CCD groups in the low-risk group are summarized in (Supplementary Table 2). Kaplan–Meier curves of OS for CCRT vs IMRT alone before and after balancing covariate bias in Stage II and III in the low-risk group are shown in (Supplementary Fig. 4). The 5 year OS of the CCRT vs. IMRT alone group in Stage II and Stage III patients after balancing covariate bias were 82.1 vs 86.4% (p = 0.287) and 88.5 vs 83.5% (p = 0.214), respectively.

Figure 5 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to different CCD groups before and after weighting in Stage II and Stage III patients in the low-risk group. The 5 year OS of Stage II patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 after balancing covariate bias were 86.4, 71.8, 78.8 and 88.1% (p = 0.332), respectively, and in Stage III they were 83.5, 76.9, 85.5 and 95.5% (p = 0.044), respectively. Figure 6 shows a forest plot of the prognostic value of the categorized CCDs for Stage II and III patients in the low-risk group before (Fig. 6A) and after (Fig. 6B) weighting. Compared with CCD = 0 mg/m2, the death hazard ratio for 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 in Stage II patients after weighting were 4.81 (95%CI, 0.75–30.92) (p = 0.10), 2.03 (95% CI 0.77–5.35) (p = 0.15) and 0.51 (95% CI 0.09–2.94) (p = 0.45), respectively. In Stage III, they were 1.28 (95% CI 0.34–4.83) (p = 0.72), 0.87 (95% CI 0.43–1.79) (p = 0.71) and 0.30 (95% CI 0.10–0.85) (p = 0.02), respectively (Fig. 6).

Nephrotoxicity

A total of 75/354 (21.2%) patients developed nephrotoxicity during CCRT. The incidence probability of Grade 1 nephrotoxicity in the 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 groups were 15.6% (7/45), 20.1% (35/174) and 20.7% (28/135), respectively. Five cases of grade 2 nephrotoxicity occurred in patients who received 160 (3/5), 200 (1/5) and 300 (1/5) mg/m2, as shown in (Supplementary Fig. 5). No patients developed Grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity. The renal function of these patients was normal before chemotherapy, and all of them returned to normal within 2 weeks. Supplementary Table 3 shows the probability of nephrotoxicity in the different CCD groups for all CCRT patients. Probability comparisons of the three groups was performed and the value of trend chi square = 0.689 (p = 0.407). The 5 year OS rates of paitents with nephrotoxicity was 82.3, and 76.7% without nephrotoxicity (p = 0.533), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore CCDs for CCRT beneficiaries and nephrotoxicity in elderly NPC patients. We found that Stage I, II & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml and Stage III, and IV elderly NPC patients undergoing CCRT could improve the OS rate. 80 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 is recommended for high-risk groups (Stage IV), and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 for intermediate-risk (Stage I, II, III & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml) and low-risk groups (Stage III & EBV DNA ≤ 2000 copy/ml). No grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity occurred in any of the CCD groups.

IMRT in combination with chemotherapy in elderly NPC patients is controversial in regard to improving treatment outcomes, and lacks further stratification and CCD analyses7,8. More precise and effective screening and CCD treatment measures are needed to guide individualized treatment for elderly NPC patients. Currently, the tumor-node-metastases (TNM) staging system is used to guide treatment and predict prognosis, however, it only takes into consideration anatomical factors and is therefore, inadequate in identifying chemotherapy beneficiaries8. That being said, EBV DNA is a valuable marker which has demonstrated high performance in risk stratification and individualized NPC treatment25. In our large-scale study, we created an RPA model using a combination of Stage and pre-treatment EBV DNA for OS that places elderly NPC patients into risk groups (low-high) to help identify those who will benefit from CCRT in order to provide optimal CCD therapy. One previous study showed that pre-treatment EBV DNA > 2010 copy/ml was associated with worse OS, DMFS and LRRFS21. Similarly, in our study, Stage I, II patients & EBV DNA < 2000 copy/ml were considered a low-risk group and the 5 year OS for Stage II patients & EBV DNA < 2000copy/ml receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 after balancing for covariate bias were 86.4, 71.8, 78.8 and 88.1% (p = 0.332), respectively (Fig. 5). Stage I, II patients & EBV DNA ≥ 2000 copy/ml patients were considered an intermediate-risk group and had a significant difference in OS between CCRT and IMRT alone (Fig. 2E). This indicates that elderly NPC patients with a high EBV DNA level may benefit from CCRT.

Considering most elderly NPC patients already have poor physiological function and low compensative capacity, the benefits of CCRT might be counteracted by its substantial impact on their normal functioning thereby resulting in numerous adverse effects26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. In Liu et al.’s7 retrospective study (54.6% in the CCRT group and 39.3% in the RT group), only 31.1% of elderly NPC patients completed 3 cycles of 80 mg/m2 concurrent chemotherapy which was much lower than in published clinical trials (52–71%)3,4,34. Similarly, in our study, there were 342 (49.4%) Stage II–IV patients who received CCD = 0, 42 (6.1%) who received 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 174 (25%) who received 80 < CCD ≤ 160, and 135 (19.5%) who received 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2. (Table 1). Moreover, nearly half of the patients in our study received CCRT, and only 18.5% received 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2. As Peng et al.9,35 found, the risk of death and locoregional relapse increases as the CCD increases from 250 to 300 mg/m2. Relatedly, Guo et al.36 reported that a CCD of 151–250 mg/m2 allowed for minimal overall complications and cisplatin-related toxicities without compromising survival, compared with a CCD of 0–150, or > 250 mg/m2. This suggests an inability to adequately tolerate chemotherapy and or that a lower cisplatin dose is the cause of the relatively poor treatment outcomes.

In order to more accurately screen for CCRT beneficiaries, we divided the CCDs into four groups and other prognostic factors, such as Stage, age, and comorbidities, which were controlled for with a weighted propensity score analysis. Patients in the low-risk group receiving CCRT vs. IMRT alone did not have a better 5 year OS rate (86.2 vs 85.0%, p = 0.81) (Fig. 2F). However, in the subgroup analysis of the CCDs, the 5 year OS of Stage II patients receiving CCD = 0, 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 after balancing the covariate bias were 86.4, 71.8, 78.8 and 88.1% (p = 0.332), respectively, and in Stage III, they were 83.5, 76.9, 85.5 and 95.5% (p = 0.044), respectively. This indicates that 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 might be recommended for Stage III patients in the low-risk group. After balancing the screening bias, a forest plot (Fig. 4B) shows that in the high-risk group, compared with CCD = 0 mg/m2, the death hazard ratios for 0 < CCD ≤ 80, 80 < CCD ≤ 160 and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 were 1.00 (95% CI 0.39–2.57) (p = 0.996), 0.46 (95% CI 0.26–0.82) (p = 0.008) and 0.48 (95% CI 0.24–0.96) (p = 0.037), respectively. In the intermediate-risk group they were 0.96 (95% CI 0.35–2.61) (p = 0.932), 0.65 (95% CI 0.34–1.24) (p = 0.191) and 0.31 (95% CI 0.13–0.75) (p = 0.010), respectively. This indicates that for patients in the high-risk group who received 80 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2, OS might be significantly improved compared with IMRT alone. While in the intermediate-risk group, a higher CCD for 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 is recommended (Fig. 4).

Cisplatin is heavily absorbed by proximal tubular cells and can lead to renal pathophysiological disorders37. Ngamphaiboon et al.11 reported that in a high CD group (> 250 mg/m2) patients had a significantly higher incidence of acute kidney disease (AKD), cisplatin-related hospitalization, all cisplatin-related toxicities, and creatinine clearance (Ccr) decline after CCRT completion. Yet, our study showed no difference in the incidence of nephrotoxicity among all CCDs, and no paitents developed grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity. This may be due to adequate hydration prior to cisplatin administration and the close monitoring of renal function during chemotherapy.

There are several limitations of this study. Owing to its retrospective design, this study only included patients who received a three-week regimen or a weekly regimen of cisplatin, which might lead to possible bias. We did not suggest a cisplatin delivery regimen or an optimal CCD. Further clinical trials are needed before such recommendations can be made. Lastly, it was a single-center study, and further validation in other institutions is needed.

Conclusions

We found that Stage I, II & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml and Stage III, IV elderly NPC patients may be CCRT beneficiaries. 80 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 for high-risk groups is recommended (Stage IV), and 160 < CCD ≤ 300 mg/m2 for intermediate-risk (Stage I, II, III & EBV DNA > 2000copy/ml) and low-risk (Stage III & EBV DNA ≤ 2000 copy/ml) groups. No grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity occurred in any of the CCD groups.

Data availability

The dataset used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NPC:

-

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- IMRT:

-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy

- RPA:

-

Recursive partitioning analysis

- EBV DNA:

-

Epstein barr virus DNA

- CRT:

-

Chemoradiotherapy

- IC:

-

Induction chemotherapy

- CCRT:

-

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- NCCN:

-

National comprehensive cancer network

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- LRRFS:

-

Locoregional relapse-free survival

- DMFS:

-

Distant metastasis-free survival

- DSS:

-

Disease-specific survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- TNM:

-

Tumor-node-metastases

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain-reaction

- AJCC/UICC:

-

American joint committee on cancer/union for international cancer control

- ACE-27:

-

Adult comorbidity evaluation 27

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operating characteristic

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

- ULN:

-

The upper limit of normal value

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain-reaction

- Ccr:

-

Creatinine clearance

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- CTCAE:

-

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- SYSUCC:

-

Sun yat-sen university cancer center

References

Wei, K. R. et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence and mortality in China, 2013. Ch. J. Cancer 36(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40880-017-0257-9 (2017).

Chan, A. T. et al. Concurrent chemotherapy-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Progression-free survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 20(8), 2038–2044. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2002.08.149 (2002).

Al-Sarraf, M. et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: Phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. J. Clin. Oncol. 16(4), 1310–1317. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1998.16.4.1310 (1998).

Lee, A. W. et al. Preliminary results of a randomized study on therapeutic gain by concurrent chemotherapy for regionally-advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: NPC-9901 trial by the hong kong nasopharyngeal cancer study group. J. Clin. Oncol. 23(28), 6966–6975. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.00.7542 (2005).

Chen, L. et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 13(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70320-5 (2012).

Caudell, J. J. et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: Head and neck cancers, version 1.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 20(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2022.0016 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Feasibility and efficacy of chemoradiotherapy for elderly patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Results from a matched cohort analysis. Radiat. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717x-8-70 (2013).

Miao, J. et al. Reprint of Long-term survival and late toxicities of elderly nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients treated by high-total- and fractionated-dose simultaneous modulated accelerated radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Oral Oncol. 90, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.01.005 (2019).

Wen, Y. F. et al. The impact of adult comorbidity evaluation-27 on the clinical outcome of elderly nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy: A matched cohort analysis. J. Cancer 10(23), 5614–5621. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.35311 (2019).

Bray, F. et al. Age-incidence curves of nasopharyngeal carcinoma worldwide: bimodality in low-risk populations and aetiologic implications. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 17(9), 2356–2365. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-08-0461 (2008).

Ngamphaiboon, N. et al. Optimal cumulative dose of cisplatin for concurrent chemoradiotherapy among patients with non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A multicenter analysis in Thailand. BMC Cancer 20(1), 518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07024-8 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Efficacy and safety of nimotuzumab plus radiotherapy with or without cisplatin-based chemotherapy in an elderly patient subgroup (aged 60 and older) with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 11(2), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.013 (2018).

Máthé, C. et al. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity aggravated by cardiovascular disease and diabetes in lung cancer patients. Eur. Respir. J. 37(4), 888–894. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00055110 (2011).

Saleh, S., Ain-Shoka, A. A., El-Demerdash, E. & Khalef, M. M. Protective effects of the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan on cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Chemotherapy 55(6), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1159/000262453 (2009).

VanderWalde, N. A. et al. Effectiveness of chemoradiation for head and neck cancer in an older patient population. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.. 89(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.053 (2014).

Coresh, J., Astor, B. C., Greene, T., Eknoyan, G. & Levey, A. S. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third national health and nutrition examination survey. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 41(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2003.50007 (2003).

Lv, J. W. et al. Hepatitis B virus screening and reactivation and management of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A large-scale, big-data intelligence platform-based analysis from an endemic area. Cancer 123(18), 3540–3549. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30775 (2017).

Zheng, Y. et al. Analysis of late toxicity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiat. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-014-0326-z (2015).

Sun, X. et al. Long-term outcomes of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for 868 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An analysis of survival and treatment toxicities. Radiother. Oncol. 110(3), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.020 (2014).

Piccirillo, J. F. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110(4), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011 (2000).

Peng, H. et al. Prognostic impact of plasma epstein-barr virus DNA in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated using intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Sci. Rep. 6, 22000. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22000 (2016).

Guo, R. et al. Proposed modifications and incorporation of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA improve the TNM staging system for Epstein-Barr virus-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 125(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31741 (2019).

Austin, P. C. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: Reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat. Med. 33(7), 1242–1258. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5984 (2014).

Buri, M., Tanadini, L. G., Hothorn, T. & Curt, A. Unbiased recursive partitioning enables robust and reliable outcome prediction in acute spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 39(3–4), 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7407 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Establishing and applying nomograms based on the 8th edition of the UICC/AJCC staging system to select patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma who benefit from induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 69, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.04.015 (2017).

Huang, W. Y. et al. Survival outcome of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A nationwide analysis of 13 407 patients in Taiwan. Clin. Otolaryngol. 40(4), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12371 (2015).

Hoppe, S. et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 31(31), 3877–3882. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.47.7430 (2013).

Piccirillo, J. F., Tierney, R. M., Costas, I., Grove, L. & Spitznagel, E. L. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA 291(20), 2441–2447. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.20.2441 (2004).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inherently poor survival of elderly patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 37(6), 771–776. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23497 (2015).

Chang, A. M. & Halter, J. B. Aging and insulin secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284(1), E7-12. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2002 (2003).

Staessen, J. A., Wang, J., Bianchi, G. & Birkenhäger, W. H. Essential hypertension. Lancet 361(9369), 1629–1641. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13302-8 (2003).

Yancik, R. Cancer burden in the aged: An epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer 80(7), 1273–1283 (1997).

Lee, A. W. et al. Evolution of treatment for nasopharyngeal cancer—Success and setback in the intensity-modulated radiotherapy era. Radiother. Oncol. 110(3), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2014.02.003 (2014).

Wee, J. et al. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with American joint committee on cancer/international union against cancer stage III and IV nasopharyngeal cancer of the endemic variety. J. Clin. Oncol. 23(27), 6730–6738. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.16.790 (2005).

Peng, L. et al. Optimizing the cumulative cisplatin dose during radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Dose-effect analysis for a large cohort. Oral Oncol. 89, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.12.028 (2019).

Guo, S. S. et al. The impact of the cumulative dose of cisplatin during concurrent chemoradiotherapy on the clinical outcomes of patients with advanced-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma in an era of intensity-modulated radiotherapy. BMC Cancer 15, 977. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1964-8 (2015).

Pan, H. et al. Anaphylatoxin C5a contributes to the pathogenesis of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 296(3), F496-504. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.90443.2008 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yiducloud (Beijing) Technology Ltd. for supporting part of the data extraction and processing.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No.SZXK013) and the Shenzhen High-level Hospital Construction Fund. The funders had no role in this study’s design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ying Huang, Yan-Ling Wu and Jin Jing designed the experiments. Shuiqing He collected data and drafted the manuscript. Yongxiang Gao performed the statistical analysis. Shuiqing He and Danjie He prepared the figures. Yan-Ling Wu and Jin Jing edited the manuscript. All the authors contributed to this article and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, YL., He, S., He, D. et al. Optimizing the cumulative cisplatin dose for concurrent chemoradiotherapy beneficiaries among elderly nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: a real world study. Sci Rep 14, 30652 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69811-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69811-8