Abstract

The extended period of coexistence between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in Europe coincided with the emergence of regionally distinctive lithic industries, signalling the onset of the Upper Palaeolithic. The Iberian Peninsula was on the periphery of pioneering Upper Palaeolithic developments, with archaeological remains primarily found in northern territories. We report the discovery of an initial Upper Palaeolithic lithic industry at Cueva Millán in the hinterlands of Iberia. This industry, termed here Arlanzian, not only represents the earliest and southernmost evidence of such industries in Iberia but also lacks a direct counterpart. However, it exhibits chronological and technological parallels with the lithic industries associated with the earliest expansion of Homo sapiens throughout Eurasia. We interpret this as potential evidence of its intrusive nature, but not necessarily associated with a migration event, as more complex scenarios derived from inter-population connectivity must be also considered. The biological identity of the Arlanzian makers remains unknown, but they coexisted with declining Neanderthal groups from neighbouring territories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Significant transformations took place in Western Eurasia during the transition from the Middle Palaeolithic (MP) to the Upper Palaeolithic (UP) (henceforth the Transition). Between ∼50 and ∼40 calibrated thousand years before present (cal kyr BP), Homo sapiens (H. sapiens) of African origin replaced and partially absorbed the indigenous Neanderthal populations1,2,3, with the Early UP (EUP) industries (e.g., Proto and Early Aurignacian) stratigraphically succeeding the MP industries (e.g., Mousterian)4,5. In certain regions, predating the start of the EUP industries, the UP emerges with the so-called “transitional” industries, some referred to as Initial UP industries (IUP)4,5 and others considered “entirely” UP industries6,7. Here, we will collectively refer to both the “transitional” and IUP industries as “initial UP” (see Table 1 and terms of use in Supplementary Text 9).

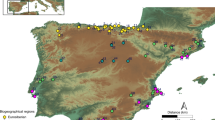

The combination of available genetic, palaeoanthropological and archaeological data suggests two major dispersal events of H. sapiens through Europe during the Transition8. The first is associated with the appearance of the IUP industries at least ∼45 cal kyr BP9,10, and possibly as far back as ∼54 cal kyr BP11 (Figs. 1 and 2, and Table 1), and related industries such as the Lincombian–Ranisian–Jerzmanowician (LRJ)12,13. Alongside this pioneering dispersal, may link to other dispersal events14,15, additional initial UP industries emerged, such as the Châtelperronian or Uluzzian (Fig. 1), with both Neanderthals and/or H. sapiens being their potential makers (Supplementary Text 9). The second dispersal corresponds to the expansion of the EUP industries ≤ 43 cal kyr BP4,5. These dispersal events occurred before the disappearance of the Neanderthals and their material culture (e.g., Mousterian) ∼40 cal kyr BP16. A longer temporal overlap between Neanderthals and H. sapiens in Europe might indicate a higher probability of interaction between both populations17, resulting in local hybridization events2.

© Servicio de Cartografía de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license (http://guiadigital.uam.es:8080/geoserver/Relieve_P_IBERICA/wms?).

Geographic location of Cueva Millán (1) and key sites showing IUP technology in Western Eurasia: 2, Mandrin Cave (Neronian); 3, Bohunice (Bohunician); 4, Bacho Kiro Cave (Bachokirian); 5, Ksâr ‘Akil (Emiran); 6, Boker tachtit (Emiran). The relief map of Iberia was edited from the source Imágenes del relieve

Comparison of the chronology obtained for the three levels of Cueva Millán and the end of the Mousterian, Châtelperronian and Aurignacian in different biogeographic regions of the Iberian Peninsula20 and El Castillo level 18127. Comparison of the Cueva Millán chronological ranges with other techno-complexes from Europe is also shown for the end of the Mousterian16, the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jezmanowician (LRJ)13, Uluzzian16 and the Châtelperronian61. Sites with Initial Upper Palaeolithic technology are also compared (Bacho Kiro I9, Mandrin E11 and Brno-Bohunice10). Horizontal black lines show the age ranges of each culture (95.4% C.I.). The vertical black lines indicate the average age of each cultural phase where the beginning and end of the cultural phase could be constrained for a given site or region. The chronological ranges of the regional techno-complexes are compared with the Greenland ice-core oxygen isotope record (NGRIP)107,108 between 62 and 30 kyr BP, with the interstadials (milder climatic periods) numbered in blue accordingly. The vertical grey bar represents Greenland Interstadial 12 and the vertical blue bar indicates Greenland Stadial 12. For details of individual chronological ranges, see Table 1—Extended Data; and for details of the dated samples for the chronological ranges of the Iberian biogeographic regions, see Table 2—Extended Data.

On the southwestern margin of Eurasia, the Iberian Peninsula emerges as a decisive region for assessing the coexistence and interaction between Neanderthals and H. sapiens18,19,20,21. The Iberian Transition is marked by significant spatio-temporal variability. The Châtelperronian and Protoaurignacian only occur in northern Iberia, while in central and southern Iberia the Mousterian persisted, alongside potential punctuated early Aurignacian incursions (see details in Supplementary Text 9.2 and Supplementary Fig. 29).

Here we present geological, environmental, subsistence and chronological data to contextualize the lithic assemblages found in the sedimentary sequence of Cueva Millán in the Arlanza River valley (northern Central Iberia, Fig. 3). Our main focus is on the discovery of an initial UP lithic assemblage in the upper part of the sequence (Level 1), which represents the earliest and southernmost evidence of such in Iberia, while lacking a direct counterpart.

© Servicio de Cartografía de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. The relief map of Iberia was edited from the source Imágenes del relieve © Servicio de Cartografía de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license (http://guiadigital.uam.es:8080/geoserver/Relieve_P_IBERICA/wms?).

Cueva Millán location. (A) The biogeographic zones (BZ) of the Iberian Peninsula20: Eurosiberian (grey), Supramediterranean (blue), Mesomediterranean (green) and Thermomediterranean (pink); (B) Cueva Millán (representing by a black start) in its geographical context; (C) Cueva Millán Rock Shelter with the Arlanza valley in the background. The relief map of Iberia come from Imágenes del relieve

Results

Cueva Millán is a small limestone rock-shelter located in the western margin of the Cameros-Demanda Massif (Iberian range) limiting the eastern boundary of the Duero basin (Spain). It occupies an intermediate position between the Cantabrian Region and the centre of the Iberian Peninsula, while also being near other major river basins like those of the Tajo and the Ebro (Fig. 3).

This site was discovered in 1975 by M.A. Martín Merino, who noted abundant flint artifacts on the surface. A year later, members of the Colectivo Arqueológico Salense (CAS) visited the site and collected a lithic assemblage from the surface. The first professional excavation was led by E.G.S. over four field seasons in the 1980s (Supplementary Text 1). More than thirty years later, in 2017, P.S.Y. resumed archaeological work at Cueva Millán. The results presented here correspond to the field seasons carried out between 2017 and 2019 (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the techno-typological characterization of the lithic record is supported by a qualitative study of the CAS and E.G.S. lithic assemblages (Supplementary Text 8), as well as by experimental work (Supplementary Text 10).

Cueva Millán excavation and sedimentary sequence. (A) Planimetry of the excavation areas in Cueva Millán; (B) Stratigraphic profiles of Sector 1A, including the chronological range and material culture of each level; (C) 2017–2019 excavation area (Sector 1A, S1A) and part of Sector 1B (S1B) with level 3 partially excavated (this level was not fully excavated in the 1980s excavation); (D) Archaeological excavation of bones (yellow pins) and lithics (green pins) in Level 1 (2018 field-season).

Stratigraphy, sedimentology and micromorphology

The sedimentary deposit of Cueva Millán consists of circa 1.1 m thick accumulation of sub-horizontally oriented, angular, limestone debris in a fine sand to silty matrix (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Text 3). The limestone debris has the same petrographic features as the cave wall and was much likely deposited by roof spall. The deposit is homogeneous, without sharp sedimentary boundaries, but shows vertical differences in the number of coarse debris and organic matter. It is divided into three stratigraphic units (L1 to L3) according to variations in clast proportion and sediment colour changes. L1 and L3 show a higher amount of angular gravel to cobble size carbonate clasts, with L3 representing a clast supported gravel. L2 consists of a sandy silt deposit with a much lower frequency of large carbonate clasts. L1 is divided into two sub-units (L1A and L1B), with the Upper sub-unit (L1A) being darker due to its high organic matter content (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Text 3). Such subdivision does not apply to the archaeological remains, which are treated as one entity, as it results from a pedogenic process affecting the upper part of L1.

Micromorphological analysis (Supplementary Text 4) reveals that L1A has a well-developed biogenic microstructure and experienced partial decalcification. L1B and L2 show bioturbation by burrowing activity of soil-dwelling mesofauna such as earthworms as indicated by dark-coloured, humus-rich parts of the groundmass and few biochannels less than 5 mm in diameter. This part of the sequence shows precipitation of secondary (pedogenic) calcite, increasing with depth down to L2.

Colour changes between L1B and L2 thus may be related with precipitation of secondary calcite. However, the different contents of coarse materials suggest that roof-spall was less during accumulation of L2 sediments. This difference strongly indicates the presence of two separate sedimentary layers, as corroborated by different magnetic susceptibilities and different deposition ages.

The sequence from L1 to L2 displays features typical of a Calcisol formed on stony slope deposits. L3 shows specific micromorphological features including few silt and clay coatings, few silt and clay cappings, and reduced abundance of primary calcite grains in the sand and silt size fractions in comparison to thin sections from L1 to L2. These features of L3 point to partial decalcification and redistribution of fine particles to form coatings and cappings. The more reddish sediment colour of L3 is probably related with a higher presence of hematite as suggested by magnetic analyses. Macroscopic and microscopic features of L3 suggest presence of a Bw soil horizon. Weakly developed silt and clay cappings were also found in the lower part of L2. Such cappings have been observed in soils and sediments affected by freeze–thaw processes22,23,24. In summary, weak translocation of fine particles on a microscale by bioturbation and possibly by freeze–thaw processes can be deduced. The integrity of the sequence is not challenged by these processes and, therefore, post-depositional processes do not play a significant role in shaping the composition of the archaeological assemblages.

Archaeobotanical record

The pollen record from upper L3 shows high proportion of grasses (Poaceae: 36.3%) and xerophytes, but low abundances of Mediterranean forests taxa (Pinus pinaster: 15.1%, evergreen Quercus: 4%), mesophilous elements (e.g., deciduous Quercus, Betula and Alnus) and hygrophytic herbs (Cyperaceae), and a relatively high percentage of junipers (Juniperus: 7.2%). These data are consistent with arid and cold conditions, reinforcing micromorphology observations for L3. By contrast, the pollen data from L1 and L2 reflect forest recovery, a landscape dominated by Mediterranean pine (Pinus pinaster: 47.7–53%) and Holm oak (evergreen Quercus: 11.7–13.9%), and a reduced percentage of Juniperus (3.7–5%). The lower xerophyte and grassland percentages and the increase of hygrophytic herbs (Cyperaceae: 8.6–10.7%) and riparian forests (Alnus: 2.7–5.1%), reflect warmer and more humid (but still dry) climatic conditions (Supplementary Text 5 and Supplementary Fig. 10). The charcoal record is consistent with the pollen data (Supplementary Table 2).

Magnetic properties

Analysis of sedimentary magnetic properties (Supplementary Text 6) reveals progressive and minor variations in magnetic susceptibility throughout the sequence (Supplementary Fig. 12), which aligns with a lack of sedimentary alteration, as confirmed by both sedimentary and micromorphological analyses. The lowest magnetic susceptibility values are at the L2/L3 sedimentary interface due to a higher presence of hematite and a lower concentration of magnetite (Supplementary Fig. 12). These mineralogical differences reflect variations in lithological features and soil formation process and, in turn, environmental conditions25,26. The lower magnetic susceptibility of the L2/L3 sedimentary interface agrees with the arid and cold episode suggested by the pollen record and micromorphological analysis.

Dating

A combination of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon (14C) dating of bone and charcoal, single-grain optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of sedimentary quartz (Supplementary Tables 3–6, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15; Extended data Fig. 1), and Bayesian chronostratigraphic modelling (Extended data Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 7) has been used to constrain the ages of the three stratigraphic units.

Interpretation of the 14C dating results from the Cueva Millán sequence is complicated by discrepancies between replicate bone ages obtained from two independent laboratories (ORAU and Beta), as well as inconsistent ages for charcoal samples from unit L2. These complications necessitate careful consideration of quality assurance criteria for the combined 14C dataset (see Methods). Our examination of chronological hygiene favours the ORAU ultrafiltration bone 14C ages for final dating assessments owing to completeness of the bone collagen suitability indicators, the more conservative results and uncertainties obtained for replicate samples, and the fact that older replicate 14C ages are generally considered to be more accurate than younger 14C ages where discrepancies exist towards the upper dating limit of the 14C technique; assuming that organic contaminants were not properly removed from samples yielding younger ages27.

The two charcoal 14C ages from unit L2 are not considered reliable owing to concerns over sample contamination and stringency of pre-treatment procedures (see Methods). Of the thirteen ORAU ultrafiltration 14C bone ages submitted for analysis, three failed due to low collagen yield and two more samples from L3 provided non-finite conventional 14C ages beyond the dateable 14C range (Supplementary Table 6). The remaining eight 14C ages are grouped between 51,850–43,100 cal BP and 46,350–42,300 cal BP (95.4% C.I. calibrated ranges) for unit L1, and between 49,900–42,850 cal BP and 44,450–41,850 cal BP for unit L2 (Supplementary Table 6). These new ultrafiltration 14C bone ages are systematically older than those obtained previously for units L1 and L2 using standard triple-acid pre-treatment procedures (Supplementary Table 4; 37,600 ± 700 14C yr BP and 37,400 ± 650 14C yr BP; equivalent to 42,750–41,250 cal BP and 42,550–41,200 cal BP at 95.4% C.I.)28.

The single-grain OSL equivalent dose (De) datasets for the L3 and L2 deposits are consistent with those reported for well-bleached and unmixed sediments29 (overdispersion = 15 ± 3% to 23 ± 4%; Extended data Figs. 1 B-D). Overlapping ages of 49.7 ± 3.3 ka and 50.4 ± 3.4 ka (1σ) were obtained for the two replicate OSL samples from the lower L2 deposits, while L3 yielded an OSL age of 56.2 ± 3.4 ka (Table 3—SI.5). The L1 OSL sample exhibits more pronounced De scatter (overdispersion = 39 ± 5%; Extended data Fig. 1A), likely reflecting either its closer proximity to the surface and enhanced potential for bioturbation and pedogenesis, or more significant spatial variations in beta dose rates experienced by individual grains owing to the presence of angular carbonate gravels in L1 (Supplementary Text 3, Supplementary Fig. 3). Insufficient bleaching prior to burial is not thought to have contributed significantly to the heterogeneity of the L1 De dataset as it is not significantly positively skewed30 and the minimum age model is not statistically favoured according to the log likelihood test outlined by Arnold et al.29. A weighted mean OSL age of 43.8 ± 3.5 ka is obtained for L1A/1B interface, which is in stratigraphic agreement with the three OSL ages obtained for L2 and L3 (Supplementary Table 5), as well as the L1 bone 14C ages that pass the sample quality criteria (see Radiocarbon Dating Methods).

The consistency of ages obtained using two different dating methods (14C, OSL) and materials (bone, quartz) permits calculation of combined age ranges for each artefact-bearing level using Bayesian modelling. By integrating the numerical dating results, geoarchaeological and stratigraphic information within an OxCal Bayesian framework31, we determined that L1 spans 44.8–42.9 cal kyr BP, an age range of 46.1–43.3 cal kyr BP is derived for L2, while L3 dates to 62.1–43.9 cal kyr BP (95.4% probability ranges; Extended Data Fig. 2 ; Supplementary Table 7).

Lithic assemblages

L1 at Cueva Millán exhibits a high-artefact density (n = 3161; 94,4%), whereas L2 (n = 154; 4,6%) and L3 (n = 30; 0,8%) display progressive and abrupt decrease in the lithic abundance (Supplementary Table 8). This difference in stone tool density may indicate a shift in human occupation patterns, from low-impact occupations in L3 to high-impact occupations in L1. Differences in the use of raw-materials suggest a shift in the techno-economic strategies through the sequence (Supplementary Table 9). Although raw-material provisioning relies on the same local rocks in all sedimentary units, the lithic assemblages from L1 (n = 2808; 88,8%) and L2 (n = 134; 87%) are mostly composed of flint artefacts, whereas quartzite is the most exploited rock in L3 (n = 17; 56,6%) (Supplementary Table 9).

Significant techno-typological differences exist between sedimentary units (see Supplementary Text 8). The scant lithic evidence from L3 is consistent with a Mousterian industry, but a larger sample is needed to confirm this classification. An unusual combination of MP and UP features is documented in the L1 lithic record and, to a lesser extent, in L2 (Supplementary Table 8). However, a larger sample is also necessary for the techno-cultural attribution of L2.

The MP component (i.e., Mousterian) in L1 is characterised by the production of flakes mainly through the discoid method, but the Levallois recurrent centripetal method is also present, although with a low number of associated items, as well as a large variety of sidescrapers (Supplementary Figs. 21 and 23). The UP component consists of three elements. Firstly, the implementation of the IUP core technology (sensu Kuhn and Zwyns32 and Kuhn33). This technological process initiated from crested blanks or natural ridges if available (Fig. 5), followed by a reduction that falls intermediate between surface and volumetric conceptions (semi-tournant debitage), resulting in hierarchized flat-faced and semi-rotated cores (Fig. 6). Blades and predetermined Levallois-like points, including narrow-based and microlithic points, are then produced sequentially through blade-and-point reduction (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8; Supplementary Fig. 28), employing hard hammer percussion and occasional platform faceting (Supplementary Text 8). Secondly, structured prismatic bladelet production with diverse reduction schemes (Fig. 6), but mostly burin core technology, and a variety of core-maintenance actions (Supplementary Fig. 22). Lastly, a discrete presence of retouched backed tools (some microlithic) and UP tool types such as end-scrapers, burins, borers and truncations (Fig. 8; Supplementary Fig. 23). Such a combination of techno-typological features is unique in the current archaeological record of the Iberian Peninsula (Supplementary Text 9.2).

Upper Palaeolithic-like artefacts: bladelet with lateral marginal retouch (1), truncated blades (2–3), retouched backed tools (4–9), bladelets (10–19), blades (20–27, 35, 36, 38–40, 44, 45), fragmented blades (29–34), blades with lateral marginal retouch (37, 41), blades with Aurignacian-like retouch (42–43). Artefacts come from the current excavation (1–6, 8–32, 36, 38–41, 44, 45) and the 1980s excavation (7, 33–35, 37, 41–43).

The impact of IUP technology on the L1 assemblage is underscored not just by the presence of flat-faced and semi-rotated cores —duplicating the bifacial recurrent centripetal ones (Mousterian-like)— or the Levallois-like points and blades, but also by the abundance of flakes potentially associated with the reduction of these cores (Supplementary Text 8), as we have also experimentally confirmed (Supplementary Text 10; Supplementary Fig. 35). The abundance of flakes in L1 can be attributed to the intense knapping activity performed on-site, reminiscent of workshop setting (Supplementary Table 8; Supplementary Text 1). The relatively high presence of prismatic bladelet cores —duplicating the bifacial recurrent centripetal ones— strengths the relevance of the UP component in the L1 assemblage.

Faunal remains

A total of 514 macrofaunal remains were analysed, most of them from L1, including the 25% of the small and indeterminate remains recovered and grouped in general bags during the excavation. 80% (NR = 368) correspond to un-identifiable specimens. The faunal remains are characterised by high fragmentation, most of them (> 83%) smaller than 3 cm, which makes the anatomic and taxonomic identification challenging. Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) analysis of 99 bones was used to aid identification of previously indeterminate remains and enhance knowledge of the taxonomic composition of the site.

The faunal assemblage is represented almost entirely by ungulates, and no carnivores or carnivore activity were identified at the site, except for a diaphysis with scores and crenulated edges in L2. L3 and L2 are extremely poor in faunal remains, mainly composed of caprids and equids, while L1 is taxonomically more diverse and richer (Supplementary Table 34). The most abundant species in L1 are Equus sp. and Cervus elaphus, followed by Capra pyrenaica and Rupicapra rupicapra. ZooMS analyses additionally identified the presence of Sus scrofa at this level, which was not previously recognized during the archaeozoological study. ZooMS also showed that most of the not identified by traditional morphological approaches belonged to equids, cervids and caprids (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31), confirming the wider archaeozoological results. The identified species are adult individuals, mainly represented by isolated dental remains followed by long bone shafts of the appendicular skeleton through the three sedimentary units. Diaphysis fragments are especially abundant in the whole assemblage. Among the indeterminate remains, ungulates of size 3–4 and 4–5 predominate. No significant changes have been observed in anatomical and taxonomic representation, neither in the size distribution of the remains, among the different levels.

17% (NR = 8) of the total remains from L2 and 13.6% (NR = 63) from L1 showed anthropogenic modifications (including cut marks, percussion marks, thermoalterations and green fractures), predominantly found on the long bones of medium-large ungulates, including red deer, horse, and ibex. On the contrary, the L3 assemblage does not show any evidence for human activity (Supplementary Table 35). Thermoalterations are the predominant anthropogenic modification (NR = 5 in L2 and NR = 31 in L1), mostly presenting a black coloration. Besides, the presence and morphology of cut marks on the diaphysis of an ibex humerus in L1 have been associated with defleshing activity (Supplementary Fig. 32). In this level, ZooMS analysis has also allowed for the taxonomic identification of some isolated bone flakes on horse remains. Most of the documented bone fractures are indeterminate, but fresh fractures associated with marrow extraction were confirmed (one bone in L2 and ca. 9% in L1) in ibex an horse long bones.

Regarding other post-depositional alterations, concretion, root vermiculation, and the presence of manganese (at a low level) are frequent through the whole assemblage. This has affected the legibility of the cortical surface of a significant percentage of the remains, making it difficult to identify cut marks or carnivore marks.

Discussion

Origin of the multicomponent nature of the L1 lithic record

The most distinctive feature of the Cueva Millán sequence is the unique combination of MP and UP techno-typological features in L1, and to a lesser extent in L2. To evaluate its significance, it is essential to determine whether this mixture is of anthropogenic origin or the outcome of post-depositional processes.

Multiple lines of evidence support the integrity of the archaeo-sedimentary sequence. The micromorphology analysis excludes sediment mixing and, in turn, vertical mobility of archaeological items as relevant factors contributing to the composition of the archaeological assemblages. This conclusion is strengthened by further evidence, including the single-grain OSL datasets (low overdispersion, limited De scatter, and normally distributed De datasets), distinct variations in texture and colour among the sedimentary units, a consistent magnetic susceptibility profile, the reassembling of lithic artefacts and bones within the same stratigraphic units (Extended data Figs. 3 and 4), and a collection of direct ages from all layers that show no significant outliers within the sequence, once selected according to quality assurance criteria. Additionally, the absence of taphonomic signals in both lithic and faunal remains—such as rounding and abrasion that would suggest transport by natural processes—along with the abundance of lithic debris and the uniformity in the preservation, skeletal, and taxonomic representation of the faunal remains, also supports the integrity of the sequence.

Therefore, the available evidence suggests that the multicomponent nature of the L1 lithic record is very likely of anthropogenic origin. It might be attributed to either (i) a palimpsest of MP and UP occupations or (ii) a cohesive cultural entity. Based on techno-typological and chronological criteria, we can confidently dismiss a palimpsest between late Mousterian and EUP occupations, or even more advanced UP phases. Firstly, classic EUP diagnostic elements, as well as Châtelperronian points, are both conspicuously absent. Secondly, once critically examined, the OSL and radiocarbon dates, whether analysed individually or modelled (Extended data Tables 1 and 2), predate the earliest UP evidence in Iberia (i.e., Châtelperronian and Protoaurignacian). Therefore, a hypothetical palimpsest would involve late MP and initial UP occupations. However, the diagnostic items of both technologies do not show a distinct vertical distribution or an interstratified structure along the sequence—co-occurring adjacent to each other (Extended Data Fig. 5)—strengthen the hypothesis of a cohesive cultural entity rather than a palimpsest hypothesis. Nonetheless, variations in the vertical distribution of artifacts could potentially be detected in an open area excavation, providing additional data to test the palimpsest hypothesis.

Scenarios for the nature and origin of the Arlanzian

Considering the current evidence, the hypothesis that the L1 assemblage embodies a cohesive cultural entity emerges as the most parsimonious. For ease of communication, we will refer to this entity as the “Arlanzian”. The subsequent scenarios may explain its nature and origin: (i) indigenous populations (i.e., Neanderthal) from inland Iberia independently developed an initial UP technology, with the Arlanzian representing an evolved techno-cultural tradition emerged from the local Mousterian substrate (i.e., evolved Mousterian); (ii) demic diffusion, with the Arlanzian being a result of the migration of groups to Iberia (i.e., Neanderthals or H. sapiens) bearing initial UP technologies; (iii) cultural diffusion, with the Arlanzian being a result of direct or indirect technological transfer between groups bearing Mousterian (i.e., Neanderthals) and initial UP technologies (i.e., Neandertals or H. sapiens).

The time-clustered pattern associated with the start of the initial UP industries in Europe, the majority emerging between 48–44 cal kyr BP9,10,13,16, with the Neronian dating back ∼54 cal kyr BP11 (Table 1), raises questions about independent evolution as the primary mechanism for their emergence. If that was the case, the start of each initial UP industry would have occurred separately from the others, resulting in a more randomly distributed temporal pattern throughout the MP period than is currently observed34. Given that Cueva Millán L1 fits into this temporal pattern and displays technological parallels with some of these industries, the scenario of independent local evolution seems less plausible.

The intricate population landscape during the Transition17 points to a complex interplay of factors that likely influenced the appearance and dissemination of initial UP industries in Europe. Recent ancient DNA analysis have shed light on the significance of population migration as a key mechanism2,13. Moreover, it is worth noting that local hybridization between Neanderthal and H. sapiens ocurred2, albeit probably not consistently3. However, the prolonged coexistence between both populations in some European regions17 could have led to episodes of interbreeding35,36,37and cultural exchange events19,38,39. Under this scenario, inter-population connectivity would have played a pivotal role in the emergence and dissemination of the initial UP industries34, through close and long-distance population displacements (demic diffusion)15 and direct or indirect cultural diffusion within and between populations40. Along with both diffusion vectors, local adaptations and innovations may take place32,33, contributing to the evolution and diversification of the initial UP entities12,40.

Although interaction between Neanderthals and H. sapiens seems to have occurred in Europe17, several questions still need to be addressed. First, it remains unclear why all early European H. sapiens that yield genomic data have recent Neanderthal ancestors in their immediate family histories, but there is currently an absence of evidence for gene flow from early H. sapiens into late Neanderthals41. These observations also need to be reconciled with potential signs of hybridisation noted in some late European Neanderthal fossil remains42,43. Second, further evidence is required to identify the contact territories and the frequency of such interaction. Despite extensive research, there is limited conclusive evidence of contemporaneity or interaction between the two populations at any European location or territory11,17,19.

Summarising, the available evidence suggests that the multicomponent nature of the L1 lithic assemblage at Cueva Millán is of anthropogenic origin and likely represents a cohesive initial UP cultural entity (i.e., Arlanzian). Considering the chronological and technological parallels between the Arlanzian and other initial UP industries, along with the prolonged coexistence of Neanderthals and H. sapiens in Europe that likely resulted in a complex population landscape, inter-population connectivity within and between both human taxa provides a plausible framework to contextualize the origin and nature of the Arlanzian.

Formative phase of the Upper Palaeolithic

During this coexistence period, regionally distinctive cultural entities emerged, including the Arlanzian, marking the onset of the UP. These entities, referred to here as initial UP and encompassing both the so-called “transitional” and the IUP industries (Table 1; Supplementary Text 9.1), often exhibit a complex nature situated at the boundary between the MP and UP. This may explain why they have undergone multiple techno-cultural assignments, highlighting the challenges and complexity involved in their classification (Supplementary Text 9.1).

For instance, the range of industries traditionally designated as IUP (Table 1) demonstrate a significant degree of technological heterogeneity32,33, to the extent that entities or assemblages categorized under this term may reflect distinct archaeological realities depending on the influence of the MP technological substrate44,45,46,47. To mitigate ambiguities, the implementation of the crested blade technique within the IUP technology is considered the primary departure from the Levallois technology, marking the first phase in the gradual transition from a surface exploitation to a volumetric exploitation33,47,48. Thereby, the IUP cores start as UP but often finish as MP49, and some resulting end-products (blades and points) and cores (flat-faced) may resemble artefacts of Levallois manufacture33. However, the emergence of cresting and volumetric exploitation was the result of convergent evolution among human groups with a MP/Levallois technological background interested in elongated blanks as, for instance, suggested by their intermittent presence in MP assemblages between MIS 7 and MIS 5 in Europe50.

Therefore, the pioneer UP cultural entities (i.e., initial UP) are characterized by unique combinations of derived (UP) and basal (MP) techno-typological features. The emergence of these “industries in transition” does not signify a complete departure or rupture from the MP. Rather, it indicates the presence of a formative phase at the onset of the UP, characterized by a techno-typological gradient shaped by diverse regional expressions (i.e., initial UP industries) predating the EUP industries. The appearance of the EUP industries marked the consolidation of the UP technologies (i.e., consolidation phase) (Table 1).

Classification of the Arlanzian

The Arlanzian is characterized by a combination of derived and basal techno-typological features, anticipating the UP lithic technologies (e.g., blades, bladelets, cresting, backing and microlithics), while retaining MP features (flake-based productions and tools). Accordingly, it corresponds to an initial UP characterization (Supplementary Text 9.1).

One of the most distinguished features of the Arlanzian industry is its parallels with the IUP technology32,33, stressing the implementation of the cresting technique and the very specific “schéma croisé” flaking mode11, where a ventral surface of a core-on-flake serves as a production plane, following a blade-and-point reduction. Nonetheless, we avoid subsuming the Arlanzian under the IUP bio-cultural phenomenon. This phenomenon includes a range of cultural entities showing IUP core technology and associated with the expansion of H. sapiens across Eurasia11,38. The cultural phylogenetic relationship between these entities is not clear and distinct techno-typological realities may be grouped under this term33,44,45.

Given the complex population landscape during the Transition, the scarcity of associated fossil remains and DNA data, and the vast geographical scale of the phenomenon articulated in separate clusters, it seems premature to conclude that all assemblages categorized as IUP would share a common origin and could be attributed to a singular hominin population or taxon33,51,52. Accordingly, it is advisable to differentiate between the IUP as a technological category (ie., IUP technology) and as a bio-cultural phenomenon (Supplementary Text 9.1).

Alternatively, given its intermediate techno-typological and chrono-stratigraphic nature between the MP and EUP industries, one could consider classifying the Arlanzian as a “transitional” entity. However, etymologically, the very term “transitional” implies a direct historical or cultural-phylogenetic connection, suggesting derivation from local MP and foreshadowing UP (Supplementary Text 9.1). This would suggest that the Arlanzian represents a transitional entity between the Mousterian and the Protoaurignacian or Châtelperronian in Iberia. It seems preferable the more neutral term “initial” UP over “transitional”, as the latter implies assuming a historical process that must be demonstrated32. However, the available data is insufficient to determine a cultural-phylogenetic relationship (i.e., ancestor–descendant) between the Arlanzian and any other cultural entity, or to confirm its affiliation with a specific human taxon. Therefore, the intermediate nature of the initial UP industries indicated that they are industries in transition rather than transitional industries.

The presence of basal features in the Arlanzian is not a sufficient condition for its characterization as MP, since it clearly diverges from the Iberian MP (Supplementary Text 9.2), portrayed as a period of technological stasis53. Moreover, assemblages rich in points, like the one found in Cueva Millán L1, are exceptional across Europe, with none documented in Iberia. The Main exceptions are MIS-5 sites in Northern France54, few MIS-3 sites in Southeastern France shaping the Neronian entity11,44, and late Mousterian assemblages from Oscurusciuto rock shelter (Southern Italy)55,56. In both the Neronian11,57 and Oscurusciuto56, the production of points and elongated blanks show significant parallels with the IUP technology, also referred as semi-tournant debitage57. Furthermore, a semi-tournant debitage reduction is a key feature of the assemblages assigned to the Mousterian of Acheulean Tradition type B (MTA-B), aimed at producing elongated blanks, some of which are retouched as backed knives58. However, many MTA-B assemblages come from old excavations, have clear recovery biases, and need taphonomic revision59.

Therefore, it seems worthwhile to explore possible connections between assemblages initially classified as late Mousterian and the IUP technology. This investigation should focus on those assemblages in secure stratigraphic and chronological contexts that demonstrate dedicated production of elongated and/or pointed blanks. This is the approach recently adopted for the Neronian11,60, Oscurusciuto56, and here.

Summarising, we classify the Arlanzian as an initial UP cultural entity (i.e., industry in transition), displaying parallels with the IUP technology alongside UP and MP techno-typological features. The parallels with the IUP technology and the absence of a direct counterpart in Iberia (Supplementary Text 9.2) could be interpreted as potential evidence of the intrusive nature of the Arlanzian, not necessarily associated with a migration event, as more complex scenarios resulting from inter-population connectivity must be also considered.

Significance of Cueva Millán in the Iberian transition

The significance of Cueva Millán lies in revealing an unexpected emergence of the UP in Iberia in technological, geographical, and chronological terms. The lithic assemblage discovered in the Upper part of the sequence exhibits a unique combination of basal and derived techno-typological features, lacking a direct counterpart in Iberia; for instance, to date, no assemblage in Iberia shows parallels with the IUP technology (Supplementary Text 9.2).

The Châtelperronian remains the sole initial UP industry identified in Iberia, potentially alongside the archaeological assemblage from El Castillo Unit 18 classified as Transitional Aurignacian (Supplementary Text 9.2). The Châtelperronian is considered intrusive, the first genuine Upper Palaeolithic industry and, accordingly, it shows no links with previous MP technology in the region61. Conversely, the Transitional Aurignacian was seen as an independent local evolution leading to the Aurignacian (i.e., in-situ transition hypothesis)62. However, the researchers currently overseeing the archaeological excavation at El Castillo cave site have abandoned the term Transitional Aurignacian and are conducting a review of this assemblage63. Accordingly, the in-situ transition hypothesis formulated to explain the origin of the EUP in northern Iberia has lost its sole anchor point in the archaeological record.

Cueva Millán stands out as the first site in Iberia to provide evidence of the initial UP south of the Cantabrian Range and the Ebro Basin (Supplementary Text 9.2; Supplementary Fig. 29), given that such occurrences are concentrated in northern territories, mostly in the Eurosiberian biogeographic region (Supplementary Fig. 29A). Additionally, Cueva Millán offers evidence of an earlier emergence of the UP in Iberia. The L1 lithic assemblage most likely predates the Châtelperronian and Protoaurignacian in Iberia, while overlapping with El Castillo Unit 18 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 29B). Simultaneously, it may postdate the end of the Mousterian in the Eurosiberian region and predate its end in central-southern Iberia, including the Supra-Mediterranean zone where Cueva Millán is located (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 29). Consequently, the Arlanzian flourished in the hinterlands of Iberia, chronologically overlapping with declining Neanderthal groups from neighbouring territories responsible for the late Mousterian and El Castillo Unit 1863,64,65.

In sum, the discovery of the Arlanzian adds a new layer of complexity to the Transition in Western Eurasia, highlighting the significance of inter-population connectivity within and between populations in this mosaic-like process. Ongoing excavations and research are being conducted in Cueva Millán not only to determine the precise nature, origin, and authorship of the Arlanzian, but also to refine its chronological framework.

Methods

Excavation

Fieldwork during the 2017, 2018 and 2019 seasons focused on excavating a 2 m2 test trench adjacent to the 1980s excavation area (Fig. 4A). We first removed the reworked sediment covering the old excavation (Supplementary Fig. 1). This area (Sector 1B, S1B) contained numerous lithic and faunal remains without stratigraphic context (Fig. 4C). However, these materials likely come from L1 and the upper part of L2; the profiles from the 1980s excavation indicate erosion in the upper part, and the excavation area was left uncovered —without being filled with sediment. We have also found that L3 had not been fully excavated in S1B down to the bedrock (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. 1A). We then dug out the test trench (Sector 1A), with excavation following standard methods in Palaeolithic archaeology: use of small excavations tools, three-dimensional recording of every archaeological object or signature by Total Station (Leica Flexline TS06), registering the orientation and dip of elongated bones and lithics, and on-site sieving of the sediment removed through nested 3 mm and 1.5 mm mesh sieves (Fig. 4D). We reached the bedrock on the base of the excavations across the whole of Sector 1A.

Micromorphology

For micromorphological investigations, five sediment blocks were obtained from key points of the stratigraphic succession and covering all stratigraphic units. The blocks were extracted from the Sector 1A-East profile after reinforcing the sediment with gypsum bandages to avoid collapse and loss of the original structure (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). In the laboratory, the blocks were dried at 40°C for at least two weeks. Afterwards, the blocks were impregnated with polyester resin under vacuum66 and left for at least six weeks for hardening. The blocks were then subsampled using a rock saw and six uncovered thin sections, 80mm x 60mm large and approximately 25µm thick were prepared by grinding and polishing. All preparations were carried out by Th. Beckmann, Schwülper-Lagesbüttel, Germany. Micromorphological analysis of the thin sections was accomplished at different magnifications, using flatbed scans at a resolution of 1200dpi (< 20x), and a polarising microscope (12.5 × to 500x). Microscopic inspection used plane-polarized light (PPL), crossed polarisers (XPL) and oblique incident light (OIL). The description of thin sections followed the guidelines of Stoops67.

Archaeobotany

A total of 5 palynological samples were collected from the Sector 1A-North profile covering the sequence (Supplementary Fig. 11). The uppermost pollen sample (L1) comes from the middle part of L1. Three samples were collected from L2, focusing on its upper (L2-u), middle (L2-m) and lower parts (L2-l). Finally, the lowermost pollen sample (L3) comes from the upper part of L3. No samples were taken from the lower part of L3 because its sediments correspond to coarse sands and pebbles in which pollen preservation is null68. The laboratory treatment was carried out in the Archaeobiology Laboratory (CSIC, Madrid) using the method by Faegri and Iversen69 with densimetric separation of microfossils70. The pollen morphotypes were established according to Faegri and Iversen69, Moore et al.71 and Reille72,73. A sample was considered valid sample, when the number of pollen grains counted or pollen sum exceeded 200 from terrestrial plants, and when there was a minimum taxonomical diversity of 20 pollen types68. In the calculation of percentages, Asterioideae and Cichorioideae were excluded from the pollen sum due to their anthropogenic character74. The relative value of the excluded palynomorphs was calculated with respect to the pollen sum. The pollen diagram (Supplementary Fig. 10) was constructed with the TILIA and TGView programs 75,76.

A total of 37 samples of charred wood were studied from Sector 1A. All the remains > 2 mm have been identified. A total of 125 fragments have been studied, 3 of them identified as bark pieces (Supplementary Text 5; Supplementary Table 2). The anthracological analysis is based on the anatomical observation of charred wood and its comparison with current wood as well as consulting different wood anatomy atlases77,78,79. The charcoal was fragmented by hand, guiding each fracture towards the three anatomical planes, and examined with a Leica DM 4000M incident light microscope, using magnifications of 50x/100x/200x/500x.

Magnetic properties

14 bulk samples were collected from the Sector 1A-East profile, covering the entire sequence with a sampling resolution of about 7 cm per sample (Supplementary Fig. 12). Low-field magnetic susceptibility (MS) was measured in every sample (average of three measurements) with a KLY-4 Kappabridge (AGICO, noise level ~ 3 × 10−8 S.I.). Additionally, representative samples from each level were selected to study in detail the magnetic properties. With the aid of a Variable Field Translation Balance, the following sequence of experiments was measured in the bulk sample (~ 450 mg): (i) progressive isothermal remanent magnetisation (IRM) acquisition curves; (ii) hysteresis loops (± 1 T); (iii) backfield coercivity curves and (iv) thermomagnetic curves (temperature dependence of magnetisation) in air up to 700 °C. Magnetic analyses were carried out at the paleomagnetism laboratory of Burgos University, Spain.

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating

Four single-grain optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating samples were collected from the three main stratigraphic units to provide estimates of when the lithic-bearing deposits were last exposed to light before to burial (Supplementary Fig. 16). Sample CUMI22-2 was collected close to the Level 1A and 1B interface on the Sector 1A North Profile. Two replicate OSL samples (CUMI-1 and CUMI-2) were collected from similar depths towards the base of Level 2 on the Sector 1A East Profile. A fourth sample (CUMI22-1) was collected from the base of Level 3 on the Sector 1A North Profile. This sample was taken immediately above the contact with the underlying bedrock (Supplementary Fig. 16). OSL samples were taken from cleaned exposure faces using metal tubes or were carefully hand-collected under opaque sheeting with the aid of filtered red LED lighting. Following extraction, the samples were immediately wrapped in opaque bags and sealed using duct tape to prevent light exposure during transportation and storage. Additional bulk sediment was collected from within a 1 cm radius of each sample position for water content and dosimetry evaluations.

Purified coarse grain quartz extracts were processed under safe light conditions (600 or 630 nm LEDs, < 0.15 μW/cm2 power density at sample position) at the Prescott Environmental Luminescence Laboratory, University of Adelaide, using standard preparation procedures80, which included a 48% hydrofluoric acid etch (40 min) to remove the alpha-irradiated outer layers of the quartz extracts. OSL measurements were made using the experimental apparatus, single-aliquot regenerative-dose (SAR) procedures, and quality assurance criteria published previously by Arnold et al.81,82 which are further detailed in Supplementary Text 7. For equivalent dose (De) evaluation, 212–250 μm diameter quartz grains were manually loaded onto aluminium discs drilled with an array of 300 × 300 μm holes to ensure true single-grain resolution83. Between 2700 and 4500 single-grain De measurements were made for each sample using the SAR procedure shown in Supplementary Table 3 which yielded suitable dose recovery test results for sample CUMI-1 (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Environmental dose rates were estimated using a combination of in situ field gamma spectrometry and low-level beta counting, taking into account cosmic ray contributions84, an assumed minor internal alpha dose rate85, beta-dose attenuation86,87 and long-term sediment water contents88,89. Gamma dose rates were calculated from in-situ measurements made at each sample position with a NaI:Tl detector (using the ‘energy windows’ approach90,91, while beta dose rates were calculated on dried and powdered sediment collected from within a 1 cm radius of each sample position using a Risø GM-25–5 low-level beta counter)92. Further details of the OSL dating procedures are provided in Supplementary Text 7.

Radiocarbon ( 14 C) dating

A total of 28 radiocarbon (14C) samples were analysed at three different laboratories (ORAU, Beta and Cologne) to provide a detailed chronology for the complete sequence of the modern excavations undertaken at Cueva Millan. 26 bone samples were selected for AMS 14C dating using ultrafiltration of gelatinised collagen: 13 samples were analysed at ORAU using conventional ultrafiltration pre-treatment procedures93,94, while 13 samples were analysed at BETA using ultrafiltration pre-treatment. Two of the 26 samples were sub-sampled for replicate analysis at both ORAU and BETA. Two additional charcoal samples were selected for 14C dating at CologneAMS using single-acid and triple-acid pre-treatment methods (Acid–Alkali–Acid extraction)95.

Radiocarbon ages are given in Supplementary Table 6 as conventional ages B.P.96 with B.P. representing radiocarbon years before present (1950 CE). To determine equivalent ages on the calendric timescale, the 14C dating results have been calibrated with the IntCal20 curve97 using OxCal v4.431,98. The following suite of analytical indicators was used to assess the quality of the bone collagen extracts and suitability of the resultant 14C ages for final chronological evaluations: % collagen (> 1), %C (30–44%), %N (11–16%), and C:N (2.9–3.6)99,100,101,102. For charcoal samples, it was not possible to apply equivalent sample purity and quality criteria owing to the limited information provided in the laboratory reports.

The available quality assurance (chemical analytical indicator) data for the 14C results obtained at Beta and ORAU are similar, with values falling within ranges considered acceptable according to the criteria outlined above. However, % collagen data is not available for the Beta 14C dataset, making it difficult to evaluate whether this sub-set of samples meets our minimum quality assurance criterion for collagen yield (> 1%). A clear systematic offset can be observed between the 14C ages obtained at the Beta and ORAU laboratories, with the Beta samples providing significantly younger ages compared to the ORAU samples. For this reason, two samples were submitted to both laboratories for replicate analysis. These replicate 14C samples (bone samples CM-2017–319 and CM-2019–456) yielded contrasting results between the two laboratories. A finite age of 27,870 ± 120 14C yr BP was obtained for sample CM-2017–319 at Beta. However, this sample was not considered suitable for dating by ORAU and failed due to a low yield. The second replicate sample (CM-2019–456) was again successfully dated by Beta, yielding a finite 14C age of 33,470 ± 200 14C yr BP. In contrast, this sample was given an OxA- “X” code by ORAU as it produced a very low pre-treatment yield (1.32 mg or 0.22%). Given that the % collagen yield of this sample falls below the ORAU minimum threshold of 5 mg, the resultant age is considered to be of limited reliability and it has been designated as a minimum age estimate by ORAU (> 36,700 ± 1800 14C yr BP). The finite age of 33,470 ± 200 14C yr BP obtained by Beta for this sample is systematically younger than the minimum age estimate of > 36,700 ± 1800 14C yr BP obtained by ORAU. Additionally, the 1σ uncertainty associated with the ORAU 14C age is nine times larger than that associated with the Beta 14C age. A similar trend in the precision data is observed across the full set of 14C ages obtained from the two laboratories; with 1σ values ranging between 1000 and 1800 14C yr BP for the ORAU samples, but only between 120 and 300 14C yr BP for the Beta samples.

Collectively, these results suggest that there is a laboratory-specific methodological reason for the 14C age offsets observed between the Beta and ORAU datasets. The empirical data indicates that the ORAU ages are founded on more conservative uncertainty considerations and seemingly more stringent, or at least more complete, quality assurance criteria (chemical analytical indicators). For these reasons, particularly the absence of full bone collagen suitability indicators with the Beta dataset (%C yield), we focus exclusively on the ORAU bone 14C dataset for final Bayesian modelling evaluations of the site.

The two charcoal 14C samples from unit L2 yield inconsistent ages of 58 ± 36 14C yr BP and 28,749 ± 155 14C yr BP (Supplementary Table 6). One of these ages indicates the presence of modern organic material or contaminants in the lower profile, while both charcoal ages underestimate all available ORAU and Beta 14C bone ages from unit L2. Unfortunately, the absence of %C yield data for these charcoal samples means it is not possible to confirm whether the extracted carbon is truly derived from wood charcoal rather than extraneous materials that may have promoted inclusion of modern contaminants. The presence of the latter is a concern with these charcoal samples as they were dated using triple-acid (AAA) pre-treatment procedures that may not be ideally suited for complete removal of organic contaminants in some Late Pleistocene settings103,104,105. In the case of sample COL7030.1.1, the potential for insufficient contaminant removal is even greater as the standard AAA extraction had to be reduced to a less stringent, acid-only (A) extraction, reflecting the poor quality of original material and limited carbon yields. Further concern about the purity of the charcoal samples is apparent from the available δ13C data (Supplementary Table 6), which vary significantly for the two samples, and, in the case of COL7030.1.1, does not reflect the expected vegetation types for the area during MIS 3106. In light of the low stringency of pre-treatment procedures, absence of wood charcoal identification prior to analysis, and concerns over potential sample contamination, we do not consider the two charcoal 14C ages from Unit L2 reliable for final Bayesian modelling evaluation of the site.

Bayesian modelling

Bayesian modelling has been used to constrain the age of the archaeological sequence at Cueva Millán and to derive combined age estimates for stratigraphic units L1, L2 and L3. For this purpose, we have only incorporated finite radiometric age estimates from this study that are considered methodologically reliable according to the quality assurance criteria detailed above; namely, (i) the four single-grain OSL ages and (ii) the eight finite 14C bone ages from ORAU that are deemed methodologically reliable according to the original laboratory reports and that satisfy the full suite of analytical indicator criteria used in this study to assess quality of bone collagen extract (i.e., % collagen > 1, %C = 30–44%, %N = 11–16%, and C:N = 2.9–3.699,100,101,102) (Supplementary Table 6).

The 14C bone ages obtained by Beta are not included in our Bayesian modelling evaluations as they lack full bone collagen suitability indicators and cannot be evaluated as meeting our minimum quality assurance criterion for collagen yield (> 1%). Moreover, two of the Beta bone samples that yielded purportedly reliable ages subsequently failed minimum yield requirements and other quality assurance thresholds when replicate analyses were performed on the same specimens at ORAU (samples CM-2017–319 and CM-2019–456) (Supplementary Table 6).

Similarly, the two charcoal 14C samples from unit L2 have been excluded from our Bayesian modelling evaluations owing to the absence of %C yield data, which means it is not possible to confirm whether the extracted carbon is truly derived from wood charcoal rather than extraneous materials that may have promoted inclusion of modern contaminants. Furthermore, the presence of soluble or modern contaminants cannot be excluded with these two samples because wood charcoal identification was not performed prior to undertaking the dating analyses and, in the case of sample CM-2019–315, it was necessary to employ a less stringent version of the ABA pre-treatment owing to the poorly preserved nature of the material (Supplementary Table 6).

Bayesian age modelling has been undertaken using OxCal4.4.4 software31. A Sequence model was constructed based on the stratigraphic ordering of individual layers at the site. L1 and L2 have each been represented as a single, grouped event within the modelling framework using the Phase command owing to uncertainties in the exact relative ordering of individual OSL and 14C dating samples collected from different parts of the sediment exposures. A single shared Boundary has been used to delineate the start of unit L1 and the end of unit L2 owing to the gradational nature of the contact between these two deposits. A separate rather than shared Boundary has been used to delineate the start of unit L2 and the end of unit L3 as there is a clearly preserved and continuous contact between these two deposits in both sampling profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3). This approach ensures the model is able to better accommodate any potential depositional hiatuses or erosional discontinuities between units L2 and L3.

The 14C ages have been included in the model with their associated 1σ uncertainties and calibrated against the IntCal20 calibration curve97. The single-grain OSL dating likelihoods have been input into the model as calendar ages before year of sample collection, together with their associated 1σ uncertainty ranges. The OxCal Date command was then used to convert the original OSL ages to years before 1950 CE prior to running the model to ensure the OSL and 14C modelling likelihoods were referenced to the same baseline timescale. The Sequence model has been run with a General t-type Outlier function31, with prior outlier probabilities of 5% equally assigned to all likelihood samples to identify potentially significant statistical outliers that do not agree with the model framework. Likelihood estimates with posterior outlier probabilities > 5% were not excluded from the final model; rather they were proportionally down-weighted in the Monte Carlo iterations98. It is worth noting that when Outlier Analysis is employed the Agreement Index is not a wholly measure of model congruency; accordingly, model Avalues are no longer quoted when the outlier models are used11,16. The OxCal Date function31 has been used to calculate the modelled age of each layer from the posterior probabilities of the associated start and end Boundary.

The model was run using 300,000 iterations and repeated five times to check consistency of results. These replicate runs yielded no significant variation in posterior results, thus confirming acceptable levels of reproducibility. The effectiveness of the Bayesian model Monte Carlo solutions is supported by a median convergence integral of > 99% for all individual posterior distributions (Supplementary Table 7). Individual convergence integrals also exceed 99% for all but the start and end boundaries of L3, with the latter exhibiting lower convergence integrals owing to the availability of only a single likelihood for the basal layer of the sequence. None of the 12 dating likelihoods included in the model are identified as major statistical outliers: all likelihoods exhibit posterior outlier probabilities equal to, less than or slightly higher than the specified prior threshold of 5%, with 14C sample OxA-39352 returning the highest (albeit marginal) posterior outlier probability of 7% (Supplementary Table 7).

The Bayesian modelling results are summarised in the Fig. 2 of the Extended Data, where they are compared with the Greenland ice-core oxygen isotope record (NGRIP)107,108 for correlations of units L1-L3 with different climatic phases.

Lithic analysis

The lithic analysis has followed the technological approach, combining attribute analysis109,110 and reduction sequence analysis111,112,113,114. The former provides quantitative data on discrete and metric attributes related to technical aspects of each artefact category. The latter permits discriminate production stages, schemes and objectives, which is critical for defining production methods. The attributes recorded and the nomenclature chosen follow those commonly used for describing late Mousterian and early Upper Paleolithic industries61,115,116. The cultural classification of the sequence is based on the techno-typological analysis of the lithic record documented during the 2017–2019 fieldwork seasons (Sector 1A) and checked against the 1980s lithic collection of Cueva Millán (Supplementary Text 8).

Archaeozoological analysis

The archaeozoological analysis is based on the bone assemblage unearthed in Sector 1A. Anatomic and taxonomic identification were conducted using the comparative osteological collection located at the EvoAdapta laboratory at the University of Cantabria (Spain) and different osteological atlases117,118,119. All of the non-identified remains were grouped into five mammal-sized classes120. We considered four age classes: fetus/newborn (deciduous teeth and epiphyses unfused), juvenile (worn deciduous teeth and permanent teeth emerging and epiphyses unfused or fusing), adult (permanent teeth and fused epiphyses) and senile (very worn permanent teeth). The elements were quantified using the following measures: NR (Number of Remains), NISP (Number of Identified Specimens), MNE (Minimum Number of Elements) and MNI (Minimum Number of Individuals)121 . For the taphonomic analyses and bone fracture patterns, specialised bibliography and taphonomic atlases were consulted122,123.

ZooMS analysis

99 mammal bones were selected from L1-3 for ZooMS analysis. A representative sample, of different anatomical elements (mostly shafts of mammal sizes), was analysed. All remains had a minimum weight of 0.5 g and were longer than 1 cm. Bones with anthropogenic marks were prioritised as part of this this selection procedure. Burnt and poorly preserved remains were excluded.

ZooMS collagen peptide mass fingerprinting was carried out using the acid-soluble fraction as described by van der Sluis et al.124. Bone fragments were decalcified with 0.6 M hydrochloric acid overnight for approximately 18 h, centrifuged at 12.400 rpm for 1 min, and then the supernatant applied to a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off ultrafilter (Vivaspin, UK). After being centrifuged at 12,400 rpm for 20 min, 0.5 mL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added and, after this step was repeated, 100 µL of the filtrate was collected for tryptic digest (Promega, UK) at 37 °C overnight. Samples were then diluted in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid following Buckley et al.125 and co-crystalised with 10 mg/mL alpha-cyano hydroxycinnamic acid for Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometric analysis analysis. MALDI-ToF Mmass spectrometryic analysis was done carried out using a Bruker Rapiflex MALDI-ToF instrument using to collect up to 20,000 laser acquititions over the m/z range 700–3,700 and comparing the spectra compared with previously published reference spectra for European megafauna126.

Data availability

The data that support this research are available within the paper, its Extended and Data Supplementary Information. The current archaeological assemblages of Cueva Millán are housed in the Department of Prehistoria, Arqueología, Antropología Social y Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas (Prehistory Area) of the University of Valladolid (Spain). Data repositories are accessible for all researchers upon request. The lithic collection of the 1980s excavation and the CAS lithic collection are housed at Museo de Burgos (Spain) and Museo de Dinosaurios de Salas de los Infantes (Spain) respectively.

References

Fu, Q. et al. An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216–219 (2015).

Hajdinjak, M. et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic humans in Europe had recent Neanderthal ancestry. Nature 592, 253–257 (2021).

Prüfer, K. et al. A genome sequence fhrom a modern human skull over 45,000 years old from Zlatý kůň in Czechia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 820–825 (2021).

Hublin, J. J. The modern human colonization of western Eurasia: When and where?. Quat. Sci. Rev. 118, 194–210 (2015).

Picin, A., Moroni, A. & Benazzi, S. The arrival of Homo sapiens in the Near East and Europe. In Updating Neanderthals Understanding Behavioural Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic (eds Romagnoli, F. et al.) 321–347 (Elsevier, 2022).

Roussel, M., Soressi, M. & Le Hublin, J. J. Châtelperronian conundrum: Blade and bladelet lithic technologies from Quinçay. France. J. Hum. Evol. 95, 13–32 (2016).

Moroni, A. et al. Grotta del Cavallo (Apulia—Southern Italy). The Uluzzian in the mirror. J. Anthropol. Sci. 96, 1–3 (2018).

Vallini, L. Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population HubOut of Africa. Genome Biol. Evol. 14(4), evac045 (2022).

Fewlass, H. et al. A 14C chronology for the middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave Bulgaria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 794–801 (2020).

Ritcher, D., Tostevin, G., Škrdla, P. & Davies, W. New radiometric ages for the early Upper Palaeolithic type locality of Brno-Bohunice (Czech Republic): Comparison of OSL, IRSL, TL and 14C dating results. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 708–720 (2009).

Slimak, L. et al. Modern human incursion into Neanderthal territories 54,000 years ago at Mandrin. France. Sci. Adv. 8(6), eabj9496 (2022).

Demidenko, Y. & Škrdla, P. Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician Industry and South Moravian Sites: A Homo sapiens Late Initial Upper Paleolithic with Bohunician Industrial generic roots in Europe. J. Paleolit. Archaeol. 6, 17 (2023).

Mylopotamitaki, D. et al. Homo sapiens reached the higher latitudes of Europe by 45,000 years ago. Nature 626, 341–346 (2024).

Moroni, A., Boscato, P. & Ronchitelli, A. What roots for the Uluzzian? Modern behaviour in Central-Southern Italy and hypotheses on AMH dispersal routes. Quat. Int. 316, 27–44 (2013).

Slimak, L. The three waves: Rethinking the structure of the first Upper Paleolithic in Western Eurasia. Plos One 18(5), e0277444 (2023).

Higham, T. et al. The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance. Nature 512, 306–309 (2014).

Vidal-Cordasco, M. et al. Neanderthal coexistence with Homo sapiens in Europe was affected by herbivore carrying capacity. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi4099 (2023).

Marín-Arroyo, A. B. et al. Chronological reassessment of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition and Early Upper Paleolithic cultures in Cantabria Spain. Plos One 13, e0194708 (2018).

Djakovic, I., Key, A. & Soressi, M. Optimal linear estimation models predict 1400–2900 years of overlap between Homo sapiens and Neandertals prior to their disappearance from France and northern Spain. Sci. Rep. 12, 15000 (2022).

Vidal-Cordasco, M., Ocio, D., Hickler, T. & Marín-Arroyo, A. B. Ecosystem productivity affected the spatiotemporal disappearance of Neanderthals in Iberia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01861-5 (2022).

Zilhão, J. The late persistence of the Middle Palaeolithic and Neandertals in Iberia: A review of the evidence for and against the “Ebro Frontier” model. Quat. Sci. Rev. 270, 107098 (2021).

Mallol, C. Goldberg. P. Cave and Rockshelter Sediments. In Archaeological soil and sediment micromorphology (eds Nicosia, C. & Stoops, G.) 359–381 (Wiley, 2017).

van Vliet-Lanoë, B., Cox, C.A. Frost Action. In: Stoops, G., Marcelino, V., Mees, F. (Eds.), Interpretation of Micromorphological Features of Soils and Regoliths (Second Edition). Elsevier, pp. 575–603 (2018).

Angelucci, D. E. et al. New insights on the Monte Fenera Palaeolithic, Italy: Geoarchaeology of the Ciota Ciara cave. Geoarchaeology 34, 413–429 (2019).

Ellwood, B. B. et al. Identification of the last glacial maximum in the Upper Paleolithic of Portugal using magnetic susceptibility measurements of Caldeirao cave sediments. Geoarchaeology 13, 55–71 (1998).

Evans, M. E. & Heller, F. Environmental Magnetism: Principles and Applications of Environmagnetics (Academic Press, 2003).

Higham, T. European middle and Upper Palaeolithic radiocarbon dates are often older than they look: Problems with previous dates and some remedies. Antiquity 85, 235–249 (2011).

Moure-Romanillo, A. & García-Soto, E. Cueva Millán y La Ermita: dos yacimientos musterienses en el valle medio del Arlanza. Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología 49, 5–30 (1983).

Arnold, L. J. & Roberts, R. G. Stochastic modelling of multi-grain equivalent dose (De) distributions: Implications for OSL dating of sediment mixtures. Quat. Geochronol. 4, 204–230 (2009).

Arnold, L. J., Roberts, R. G., Galbraith, R. F. & DeLong, S. B. A revised burial dose estimation procedure for optical dating of young and modern-age sediments. Quat. Geochronol. 4, 306–325 (2009).

Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Kuhn, S. L. & Zwyns, N. Rethinking the initial Upper Paleolithic. Quat. Int. 347, 29–38 (2014).

Kuhn, S. L. Initial Upper Paleolithic: A (near) global problem and a global opportunity. Archaeol. Res. Asia 17, 2–8 (2019).

Greenbaum, G., Friesem, D. E., Hovers, E., Feldman, M. W. & Kolodny, O. Was inter-population connectivity of Neanderthals and modern humans the driver of the Upper Paleolithic transition rather than its product?. Quat. Sci. Rev. 217, 316–329 (2018).

Villanea, F. A. & Schraiber, J. G. Multiple episodes of interbreeding between Neanderthal and modern humans. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3(1), 39–44 (2019).

Stringer, C. & Crété, L. Mapping interactions of H. neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens from the fossil and genetic records. PaleoAnthropol. 2022(2), 401−412 (2022).

Lasi, L. N. et al. Neandertal ancestry through time: Insights from genomes of ancient and present-day humans. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.13.593955 (2024).

Hublin, J. J. et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave Bulgaria. Nature 581, 299–302 (2020).

Nigst, P. R. The Early Upper Palaeolithic of the Middle Danube Region (Leiden University Press, 2012).

Jöris, O., Neruda, P., Wiśniewski, A. & Welss, M. The late and final middle Palaeolithic of Central Europe and Its contributions to the formation of the regional Upper Palaeolithic: A review and a synthesis. J. Paleolit. Archaeol. 5, 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-022-00126-8 (2022).

Hajdinjak, M. et al. Reconstructing the genetic history of late Neanderthals. Nature 555, 652–656 (2018).

Compton, T. et al. The morphology of the late Pleistocene Hominin remains from the site of La Cotte de St Brelade, Jersey (Channel Islands). J. Hum. Evol. 152, 102939 (2021).

Harvati, K. & Ackermann, R. R. Merging morphological and genetic evidence to assess hybridization in Western Eurasian late Pleistocene Hominins. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1573–1585 (2022).

Ruebens, K. et al. The late middle Palaeolithic occupation of Abri du Maras (Layer 1, Neronian, Southeast France): Integrating lithic analyses, ZooMS and radiocarbon dating to reconstruct Neanderthal hunting behaviour. J. Palaeolithic Archaeol. 5, 4 (2022).

Teyssandier, N. Us and them: How to reconcile archaeological and biological data at the middle-to-Upper Palaeolithic transition in Europe?. J. Palaeolithic Archaeol. 7, 1 (2024).

Tsanova, T. S. Diachronic view of flake production from the Beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic in Eastern Balkans. In Flakes Not Blades: The Role of Flake Production at the Onset of the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe (eds Pastoors, A. & Peresani, M.) (Neanderthal Museum, 2012).

Zwyns, N. The initial Upper Paleolithic in central and East Asia: Blade technology, cultural transmission, and implications for human dispersals. J. Palaeolithic Archaeol 4, 19 (2021).

Goder-Goldberger, M., Barzilai, O. & Boaretto, E. Innovative technological practices and their role in the emergence of initial Upper Paleolithic technologies: A view from Boker Tachtit. J. Paleolit. Archaeol. 6, 11 (2023).

Skrdla, P. Bohunician technology: a refitting approach. Stranska skala. In Stranska Skala (eds Svoboda, J. A. & Bar-Yosef, O.) 119–151 (Moravia, 2003).

Carmignani, L. & Soressi, M. Ahead of the times: Blade and Bladelet production associated with Neandertal remains at the Bau de l’Aubesier (Mediterranean France) Between MIS 7 and MIS 5d. PaleoAnthropology 1, 1–33 (2023).

Kot, M. et al. Is there initial Upper Palaeolithic in Western Tian Shan? Example of an open-air site Katta Sai 2 (Uzbekistan). J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 65, 101391 (2022).

Zabala, E. et al. Pleistocene sediment DNA reveals hominin and faunal turnovers at Denisova Cave. Nature 595, 399–403 (2021).

De la Torre, I. et al. Change and stasis in the Iberian middle Paleolithic. Curr. Anthropol. 54(8), 320–336 (2013).

Goval, E. et al. Levallois points and triangular flakes during the middle Palaeolithic in northwestern Europe: Considerations on the status of these pieces in the Neanderthal hunting toolkit in northern France. Quat. Int. 411, 216–232 (2016).

Vila, P. et al. Stone tools for the hunt: points with impact scars from a middle Paleolithic site in southern Italy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 850–859 (2009).

Carmignani, L., Soressi, M., Ronchitelli, A. M., Boschin, F. Artifacts without a Homeland. Rethinking the Late Middle Paleolithic at Oscurusciuto Rockshelter (Southern Italy). Abstract Book 29TH EAA Annual Meeting, 690. 30Th August – 2nd September (2023).

Moncel, M. H. et al. Late Neanderthal short-term and specialized occupations at the Abri du Maras (South-East France, level 4.1, MIS 3). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 45 (2021).

Soressi M. Le Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne du sud-ouest de la France. Discussion sur la signification du faciès à partir de l’étude comparée de quatre sites: Pech-del’Azé I, Le Moustier, La Rochette et la Grotte XVI. Thèse de l’Université Bordeaux, France (2002).

Gravina, B. & Discamps, E. MTA-B or not to be? Recycled bifaces and shifting hunting strategies Tt Le Moustier and their implication for the late Middle Palaeolithic in southwestern France. J. Hum. Evol. 84, 83–98 (2015).

Slimak, L. For a cultural anthropology of the last Neanderthals. Quat. Sci. Rev. 217, 330–339 (2019).

Ríos-Garaizar, J. et al. The intrusive nature of the Châtelperronian in the Iberian Peninsula. Plos One 17(3), e0265219 (2022).

Cabrera, V., Pike-Tay, A., Lloret, M. & Bernaldo de Quirós, F. Continuity patterns in the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition in Cantabrian Spain. In Neanderthals on the edge (eds Stringer, C. B. et al.) (Oxbow Books, 2002).

Garralda, M. D. et al. >42 ka human teeth from El Castillo Cave (Cantabria, Spain) MidUpper Paleolithic transition. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14, 126 (2022).

Navazo-Ruíz, M. et al. Late Neanderthal subsistence strategies and cultural traditions in the northern Iberia Peninsula: Insights from Prado Vargas, Burgos Spain. Quat. Sci. Rev. 254, 106795 (2021).

López-Onaindia, D., Lozano, M., Gómez-Robles, A., Arrizabalaga, A. & Subirá, E. Neanderthal teeth from Lezetxiki (Arrasate, Iberian Peninsula): New insights and reassessment. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24694 (2023).

Beckmann, Th. Präparation bodenkundlicher Dünnschliffe für mikromorphologische Untersuchungen. Hohenheimer Bodenkundliche Hefte 40, 89–103 (1997).

Stoops, G. “Guidelines for the analysis and description of soil and regolith thin sections.” Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI. 1–184 (2003).

López-Sáez, J. A., López, G. P. & Burjachs, F. Arqueopalinología: Síntesis crítica. Polen 12, 5–35 (2003).

Faegri, K. & Iversen, J. Textbook of Pollen Analysis 4th edn. (Wiley, 1989).

Goeury, C. & de Beaulieu, J. L. À propos de la concentration du pollen à l`aide de la liqueur de Thoulet dans les sédiments minéraux. Pollen Spores 21, 239–251 (1979).

Moore, P. D., Webb, J. A. & Collinson, M. E. Pollen analysis 2nd edn. (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991).

Reille, M. Pollen et Spores d’Europe et d’Afrique du Nord. Laboratoire de Botanique Historique et Palynologie, Boite, Marseille (1992).

Reille, M. Pollen et Spores d’Europe et d’Afrique du Nord. Supplement 1. Laboratoire de Botanique Historique et Palynologie, Boite, Marseille (1995).