Abstract

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) offers a viable solution to reduce the carbon footprint in the petroleum industry, and foam injection presents a promising method to achieve this while simultaneously increasing oil recovery. In this work, we studied the feasibility of CO2 foam for co-optimizing enhanced oil recovery and CO2 storage in a high-salinity carbonate formation. The simulated hydrodynamic model is a depleted formation containing 30% residual oil, with three mechanisms for CO2 storage: solubility, residual, and mineralization trapping mechanisms. The results showed that after 20 years, oil recovery during foam injection was 2.7 times higher than CO2 injection, and the CO2 stored during foam flooding was 38% higher than CO2 injection. Notably, foam injection also increased CO2 storage capacity by 2.6 times, indicating the potential to store around 2 gigatons of CO2 in the simulated model. This was attributed to the ability of foam to significantly reduce gas mobility and thus form isolated bubbles through its Jamin effect. Residual trapping was the dominant trapping mechanism, contributing to over 70% of the total CO2 trapped, attributed to the reduction in the dissolution of CO2 in brine due to the high salinity of the aqueous medium. CO2 mineralization was also studied, showing the least trapping efficiency and the dissolution trend of all the carbonate minerals. This study illustrates a novel CO2 utilization and storage technique in which CO2 is concurrently sequestered while enhancing oil recovery in a depleted oil reservoir by injecting CO2 as foam. The relevance of this study lies in its potential to provide a dual benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and boosting oil production, offering a sustainable approach for the petroleum industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oil and gas industry has been a significant contributor to the increasing levels of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels for energy production1,2, accounting for around 15% of total energy-related emissions globally3, as well as 45% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions4. As the demand for energy continues to rise, finding sustainable solutions to mitigate CO2 emissions becomes imperative. One approach to addressing this challenge is through carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), where CO2 is captured from industrial processes and power plants, then transported and stored underground to prevent its release into the atmosphere3. This approach does not only provide a means of CO2 storage but also improves the economic viability of oil production5,6. However, injecting CO2 into reservoirs comes with its challenges, primarily related to the buoyancy of CO2 compared to the reservoir fluids. CO2, being lighter, has a propensity to escape back into the surface, leading to less effective oil recovery and potential environmental consequences7,8. Overcoming these challenges is crucial to ensuring the success of CO2 injection as a sustainable and efficient technique.

Conventional CO2 injection is quite effective in recovering oil and still stores some quantity of CO2 since some CO2 gas will be trapped and can be dissolved in the reservoir brine, oil, and minerals9,10. However, if we are considering gigaton level of CO2 storage, effective strategies should be implemented. Foaming the injected CO2 poses as a promising solution to address these challenges. By generating foam with CO2 gas in a foaming liquid containing surfactants, the buoyancy issue can be mitigated. This foaming process transforms the gaseous CO2 into a stable foam, which not only improves its mobility in the reservoir but also prevents its escape back into the atmosphere11,12.

Depleted oil reservoirs are considered practical sites for this purpose since they have already been exploited for hydrocarbon production and have reached their economic limit. These reservoirs offer several advantages for storing CO2, such as their large storage capacity, proven sealing integrity, existing infrastructure, and potential for enhanced oil recovery (EOR)13,14,15. According to Hong (2022)16, depleted oil and gas reservoirs have been estimated to have a global storage capacity of between 675 to 900 Gt CO2, which is equivalent to more than 200 years of current global CO2 emissions. These sites are promising as they are well characterized from previous oil and gas operations, and they have large pressure margins for safe storage. Furthermore, the infrastructure required for CO2 injection is already in place, which reduces the cost of implementing CCUS projects. Additionally, depleted oil reservoirs can enable the recovery of residual oil through CO2 injection, which can improve the economic viability and environmental performance of CCUS projects14. Callas et al. (2022)17 reported that CO2-EOR can produce hydrocarbons with a neutral or negative carbon impact, depending on the source and transport of CO2. Therefore, depleted oil reservoirs are an effective and practical CCUS method in the oil and gas industry.

Injecting CO2 as foam rather than gas is better for CO2 storage because foam can reduce the mobility of CO2 and increase the sweep efficiency of the injected fluid12. This can help to improve the storage capacity of the reservoir and reduce the amount of CO2 required for injection. An experimental study was conducted in Foyen et al. (2020)18 where the authors mentioned that injecting CO2 as foam rather than gas can lead to significant improvements in CO2 storage. In the numerical study by Lyu et al. (2021)19, CO2 foam increased oil recovery by 32% compared to pure CO2 injection and 27% compared to Water Alternating Gas (WAG). In addition, CO2 storage capacity increased from 12% during pure CO2 injection up to 40% during Surfactant Alternating Gas (SAG) injections. The results show that foam-assisted CO2 injection can reduce gas mobility effectively by trapping gas bubbles and inhibit CO2 from buoyancy-driven migration upward, thus enhancing storage efficiency.

The mechanisms of foam generation, propagation, and stability in porous media depend on various factors, such as the injection scheme, the surfactant formulation, the reservoir heterogeneity, the presence of oil, and the temperature and pressure conditions7. However, foam can improve \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration by increasing the apparent viscosity of the gas phase, which reduces the mobility ratio between the gas and the liquid phases. This reduces the fingering and channeling of the gas phase and improves the displacement efficiency20,21. Additionally, foam reduces the density difference between the gas and the liquid phases, which reduces the gravity segregation of the gas phase. This increases the vertical sweep efficiency of the foam flood and prevents the gas from accumulating near the top of the reservoir. In the experimental work of Chaturvedi and Sharma (2021)22, foam increased the residual gas saturation in the swept zone, which enhanced the capillary trapping of \(\text {CO}_{2}\). This is a result of the snap-off and blocking mechanisms of foam in the pore throats, which prevented the gas from flowing back when the pressure gradient is reversed.

Mineral trapping is key to \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage as it is the safest mechanism of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage and can help to store \(\text {CO}_{2}\) for longer periods of time23,24. Mineral trapping involves the transformation of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into solid minerals through chemical reactions with minerals present in the reservoir rock. However, these reactions can take an extensive amount of time and are often difficult to replicate accurately in a laboratory setting. To address this challenge, the development and application of numerical simulators have become essential tools in predicting \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage over extended periods. These simulators integrate geologic, hydrodynamic, and geochemical factors to model the behavior of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the reservoir over time accurately. With these simulators, 2D and 3D models can be developed to examine the mechanisms occurring during mineral trapping and how they affect its efficiency23,25,26,27.

Therefore, in this work, we have conducted a numerical simulation of foam injection for combined EOR and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage in a depleted carbonate oil formation characterized by high salinity. The objective is to understand how foam can improve storage capacity. The novelty of this study lies in its focus on depleted oil reservoirs, unlike numerous studies that have previously explored \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration mechanisms in saline aquifers. Additionally, this work analyzes three \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping mechanisms (residual, solubility, and mineralization) for both \(\text {CO}_{2}\) and foam injections in relation to \(\text {CO}_{2}\) utilization and storage. Depleted oil formations present unique challenges and opportunities, particularly for simultaneous EOR and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage. Furthermore, we aim to study how these processes mutually enhance each other. A storage capacity function introduced earlier by Bello et al. (2023)12 has been applied to better understand these dynamics.

Simulation Materials and Methodology

Reservoir model description

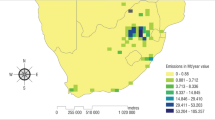

The reservoir model, shown in Fig. 1, is characterized by a grid structure of 38x45x13 dimensions. This model has been used in Bello et al. (2023)23 for sensitivity analysis of parameters affecting mineralization trapping. The porosity of the reservoir varies between 25.5% and 40.2%, averaging at 34.96%, while the mean permeability is 158 mD. The distribution of the porosity and permeability values is presented in Fig. S1 in the supplementary information document to show the degree of heterogeneity in the geological model. A summary of the model parameters can be found in Table 1.

Fluid model

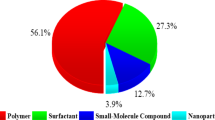

In our study, we consider a depleted oil reservoir with a residual oil saturation of 0.3. The reservoir oil is represented by a 13-component PVT model based on the Peng-Robinson equation of state. The dissolution of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into oil is also modelled based on this PVT model. The relative permeability curves can be seen in Fig. S2 in the supplementary information document. The composition of the oil model is presented in Fig. 2

Assumptions and governing equations

The governing equation for the combined process is based on the principle of mass conservation, which applies to every component present in the fluids. The mass conservation equation describes the changes in fluid saturation over time within the reservoir. For each fluid phase, the equation can be written as28,29:

where \(\phi\) is the porosity of the reservoir rock; \(\rho\) is the density of phase i; \(\hbox {S}_i\) denotes the phase saturation; v is the Darcy velocity, and Q represents any source/sink terms, depending of the phase, i could be o, w or g, representing oil, water and gas, respectively30.

Here, \(\hbox {k}_{ri}\) is the relative permeability of phase, i, \(\mu _{ri}\) is the viscosity of phase i, and \(\hbox {P}_i\) is the pressure gradient of phase, i.

Modelling of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping mechanisms

In our study, we employed a compositional simulator (CMG-GEM) to represent the displacement and sequestration processes. Compositional simulators rely on equations of state (EOS) with theoretical parameters capable of forecasting the fluid behavior of typical hydrocarbons found in oil and gas reservoirs19,31

. Specifically, the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) module within this simulator was employed to simulate \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection and sequestration into a depleted oil formation, as well as oil production, alongside aqueous phase chemical reactions, mineral precipitation, and dissolution processes. Modeling \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage involves solving component transport equations, equations governing thermodynamic equilibrium between gas and aqueous phases, and geochemical equations accounting for reactions between aqueous species and mineral precipitation/dissolution. In this work, the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration mechanisms modeled include solubility, residual, and mineralization trapping mechanisms.

The solubility mechanism was modeled using the equality of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) fugacities in the gas and aqueous phases. This is because the dissolution of gases in a liquid proceeds very fast and the phases are assumed to be in thermodynamic equilibrium which is governed by the equality of fugacity in both phases. Upon injection, \(\text {CO}_{2}\) dissolves in the aqueous phase and can be represented by Eq. 3

where \(\hbox {f}_{CO_2, g}\) is the gas fugacity from PR-EOS and \(\hbox {f}_{CO_2, aq}\) is the fugacity of the aqueous phase obtained from Henry’s law

where \(H_{CO_2, aq}\) is the Henry’s constant for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) solubility in brine and \(y_{CO2, aq}\) is the mole fraction of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in brine.

Residual trapping is another important sequestration mechanism, as it converts \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into an immobile phase in the pores through capillary effect and imbibition because \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is first injected displacing the wetting phase (oil/water), hence the mechanism is considered a drainage process. After the injection has stopped, the water migrates to the pore spaces where the gas was injected (imbibition process) to generate hysteresis32,33. Thus, the residual gas saturation is calculated as the gas trapped when the water has imbibed into the rock from a state of irreducible water saturation to a state of zero capillary pressure. Land’s model34 is commonly used to determine the trapped gas saturation as follows:

In these equations, \(S_{gt}\) is the residual gas saturation corresponding to \(S_{gi}\), and \(S_{gi}\) is the gas saturation value (\(S_{g}\)) when the shift to wetting phase saturation occurs. C is Land’s coefficient, \(S_{g, max}\) and \(S_{gt, max}\) represent maximum gas saturation and maximum residual saturation/maximum trapped gas saturation, respectively.

In our work, residual gas trapping was simulated by using a value for the maximum residual gas saturation. Holtz (2002)35 and Kumar et al. (2005)36 have validated a theory and developed a correlation (Eq. 7) that porosity (\(\phi\)) is the petrophysical property that influences the value of maximum residual gas saturation the most. Thus, an average value, calculated based on this correlation, was included in our model.

When \(\text {CO}_{2}\) mixes with water, \(\hbox {H}^+\), \(\hbox {HCO}_3^-\) and/or \(\hbox {CO}_3^{2-}\) ions are released in the chemical reactions, which serve as the basis to model the intra-aqueous chemical reactions for the geochemical reactions. The chemical equilibrium reactions are governed by the following chemical equilibrium constants37:

\(\hbox {CO}_2\)(aq) + \(\hbox {H}_2\)O \(\longrightarrow\) \(\hbox {H}^{+}\) + \(\hbox {HCO}_{3}^{-}\)

\(\hbox {HCO}_{3}^{-} \longrightarrow\) \(\hbox {H}^{+}\) + \(\hbox {CO}_3^{2-}\)

Dissolved \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is acidic and can cause the dissolution of various resident rock minerals and can in turn cause the formation of complex cations with the bicarbonate ion, which will react with different metal ions present in the formation to precipitate carbonate minerals. Although this is believed to be a very slow process and can take up to hundreds of years to complete, it is still considered a desirable process because of its safety and long-term storage of \(\text {CO}_{2}\).

Geochemical reactions between mineral and aqueous components drive the mineralization trapping mechanism, influencing the sequestration of \(\text {CO}_{2}\). Changes in mineral moles are attributed to dissolution or precipitation and they provide insights into the extent of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration via mineralization trapping. We have previously conducted X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis to determine the mineral composition, and we obtained data on the formation water chemistry for the target formation. These details are outlined in Tables 2 and 3.

Based on these results, the geochemical reactions considered in our simulation model and their reaction kinetic parameters are given in Table 4. Except for the volume fraction, which is based on XRD results, all other parameters are standard values from the compositional simulator. The K-values provided are for \(\hbox {25}^0\)C but are adjusted by the simulator to the reservoir temperature of \(\hbox {41}^0\)C during the calculations.

The mineral dissolution and precipitation reactions are modeled in the compositional simulator following the rate law equation, given by Nghiem and Li (1984)39:

where \(r_{\beta }\) is the reaction rate for a given mineral, \(\beta\), \(R_{mn}\) is the number of mineral reactions, \(A_{\beta }\) is the reactive surface area and the \(k_{\beta }\) is the rate constant of mineral reactions. \(Q_{\beta }\) is the activity product of the mineral reaction.

Foam modelling

The compositional simulator has a foam injection model that uses an empirical approach to interpolate gas relative permeability curves with and without foam. This interpolation is facilitated by a scaling factor, which reduces gas relative permeability when foam is present.

where \(k_{rg}^{f}\) is the foam relative permeability and \(k_{rg}\) is the gas relative permeability and FM is the mobility reduction factor.

The mobility of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is adjusted by the inverse mobility factor, denoted as FM, which also serves as the apparent viscosity of the foam38. The scaling factor, FM, dictates foam behavior and relies on seven parameters. It is expressed by an equation where its values range from 0 to 1, signifying the absence of foam to the generation of strong foam, respectively. Parameters \(F_1\) to \(F_7\) account for various factors: foaming agent concentration (\(F_1\)), oil’s detrimental effect (\(F_2\)), flow velocity concerning shear thinning (\(F_3\)) and generation effects (\(F_4\)), oil composition (\(F_5\)), salinity effect (\(F_6\)), permeability dependence (\(F_7\)). \(F_{dry}\) in Eq. 10 represents the foam dry-out effect and can be computed with Eq. 11.

A detailed description of each dependent F function used in this study and their values are provided in the Supplementary information document.

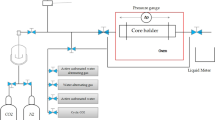

Simulation Methodology

4 injection wells and 2 production wells were placed in the reservoir. The injectors were placed to inject pure \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into the bottom layers, by perforating the last 7 layers. Injection and production were controlled by setting the bottom-hole pressures to 25 MPa and 18 MPa, respectively. This was based on a prior sensitivity analysis to guarantee that some \(\text {CO}_{2}\) remains in the reservoir after the wells are shut in. Following 20 years of injection and production, all wells were shut in, and the remaining \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the reservoir model is monitored over an additional 80 years, analyzing various storage mechanisms. In our previous work40, we used the same oil model as in this study and determined the minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) to be around 10 MPa. Therefore, this study involves miscible \(\text {CO}_{2}\) flooding, as the injection was conducted above the MMP. At the well shut-in time, the oil recovery factor was calculated.

Two scenarios were considered for foam injection. The first involves using the empirical foam model of the simulator, while the second uses Surfactant-Alternating-Gas cycles at a ratio of 1:2, to replicate field conditions. In Bello et al. (2023)12, various methods of foam generation in both laboratory and field conditions were explained. A cycle ratio of 1:2 is selected to mimic the generation of the same foam quality of 75% as in the empirical foam model of the simulator for logical comparison.

Results and Discussion

Enhanced Oil recovery and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage

The results in our work show the efficiency of foams for EOR and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage, as compared to \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection. Fig. 3 below presents ternary diagrams of the simulation model, showing the distribution of the fluids under the injection techniques after 10 and 20 years. The 10-year ternary diagram represents the midpoint of the injection and production period, so we expect to see the dynamics in the fluid phases within the model. The 20-year ternary diagram signifies the end of the injection and production period, and the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) left in the reservoir at this point is an important metric for determining the amount of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) each injection technique can keep in the geological model after oil production.

As it can be seen in Fig. 3a, during gas injection, the gas sweeps a large area but predominantly migrates towards the production zone. By the end of the injection and production period (Fig. 3a, right image), a significant amount of oil remains unproduced with minimal gas available after the shut-in period. This is attributed to the gas primarily channeling through the oil zone and breaking through to the production wells, a phenomenon characterized by the high mobility difference between the gas and oil zones in several studies41,42,43. Foam significantly mitigates this by enhancing the viscosity and density of the propagation front, thereby controlling gas mobility43,44. In the scenarios of foam injection (Figs. 3b and 3c), we can see that a higher volume of gas is present in the reservoir post-production (Fig. 3b, right image and Fig. 3c, right image), indicating increased oil production, since the gas will either mix with the oil/water or fill into the pore spaces that were earlier occupied by the produced oil. Therefore, the enhanced oil production during foam injection is at least 2.3 times higher (Fig. 4). As stated in the43, the foam slug effectively redistributes gas mobility within the reservoir. Therefore, compared to gas injection, the gas-dominant channels under foam injection are less noticeable, resulting in \(\text {CO}_{2}\) spreading over a larger area in the oil reservoir to increase volumetric sweep efficiency.

A clear difference is observed between the two foam techniques used. The SAG injection presents a more favorable outcome with a significant increase in oil production levels. This is because the SAG process involves the cyclic injection of surfactant solution and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) gas, leading to the in-situ generation of foam within the reservoir, which can help mitigate potential issues related to foam instability. By periodically injecting surfactants along with gas, this method ensures a continuous supply of fresh surfactant slugs into the reservoir, aiding in the stabilization of the foam structure over time. This leads to increased oil recovery rates, as opposed to injecting pregenerated foam, where the foam properties may degrade more rapidly over time.

Fig. 4 shows the oil recovery performance from the different injection strategies. The results show the effectiveness of foam in increasing the oil recovery than the gas injection. The disparity in the results of the two foam injection modes could be attributed to foamability and foam stability, earlier explained. Fig. 4 illustrates the comparative oil recovery performance for the injection techniques, highlighting the higher oil recovery factor of foam over gas injection. By using the simulator’s empirical foam model, it is quite difficult to guarantee the continued stability of foam a few meters into the reservoir45. However, generating foam in-situ with surfactant alternating gas ensures a continued presence of foam since both gas and surfactant solutions are consistently introduced, generating foam slugs at regular intervals.

Furthermore, we see in both cases of foam injection that with the surfactant solutions, \(\text {CO}_{2}\) was able to mobilize some capillary trapped oil that does not happen during gas flooding alone (Fig. 4b, red and green curves). During gas injection, oil production plateaued around the 16th year even though the producers were still operational (Fig. 4b, blue curve). This is not seen in the foam injection techniques and this suggests an improvement in the fluid properties, which could be attributed to the influence of the surfactant solution in the foaming system, thereby encouraging foam injection to provide mobility control for oil recovery.

In Fig. 3a, we showed how the injected \(\text {CO}_{2}\) flows rapidly from the injectors to the producers, which suggests that the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage might be affected since most of the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injected flows to the producer. Fig. 5 below further explains that and also shows how the various fluid phases tend to mix with \(\text {CO}_{2}\) under various injection techniques. These figures represent the moles of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the fluid phases in the reservoir throughout the simulation period. As it can be seen, during gas injection, more \(\text {CO}_{2}\) can be seen in all the phases. With foam, this is reduced and allows \(\text {CO}_{2}\) saturation in oil and water.

It can be seen that a higher mole of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is present in the gas phase during the gas injection (Fig. 5a, blue curve). At the end of the injection period, the amount of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the gas phase is 6.7 times more than that of the oil phase and 48.2 more than that of the water phase. Although we see similar figures for the foam injection, as the amount of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the gas phase is 5 times more than the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the oil phase and 40.9 times more than the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the water phase, the quantity of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) retained after production during gas injection is still lower than during foam injection (Fig. 3). This is because less oil was displaced by \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection, and majority of the gas was produced, however, in the case of foam, the gas mobility was effectively controlled.

Moreover, it appears that the reservoir pressure had already fallen below the bubble point pressure of the oil after the 10th year (Fig. 5b). This is likely why \(\text {CO}_{2}\) could not dissolve in the oil as efficiently as possible, leading to a subsequent decline in \(\text {CO}_{2}\) volume in the oil phase. Similar results were obtained in Li et al. (2011)43 where the authors stated that the phase behavior of \(\text {CO}_{2}\)-crude oil mixtures is influenced by \(\text {CO}_{2}\) dissolution, which increases saturation pressure and gas-oil volume ratio; and can lead to a reduction in the volume of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the oil phase, especially when the reservoir pressure falls below the bubble point pressure of the oil.

While these figures provide an overview of the distribution of the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) present in the fluid phases, drawing conclusions about how \(\text {CO}_{2}\) was stored would seem premature since not all of the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) was produced. Thus, in subsequent sections, we will examine in detail the contribution of each trapping mechanism to the total \(\text {CO}_{2}\) stored.

At the producer, \(\text {CO}_{2}\) can be produced in three forms: gas, oil, and water. The total \(\text {CO}_{2}\) produced is therefore calculated by summing the moles of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) component in oil, gas, and water phases at the producer. Subsequently, \(\text {CO}_{2}\) retention post-production is determined using the formula below, with the results shown in Fig. 6:

From Fig. 6, we can see that, at the end of the production period of 20 years, 25.68% of the injected \(\text {CO}_{2}\) during continuous \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection can still be potentially stored. For the foam injection methods, these values are 29.78% and 50.34%, respectively. This indicates a higher quantity of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage in the reservoir with foam injection, suggesting that foam injection allows for more \(\text {CO}_{2}\) to be retained in the reservoir for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping mechanism analysis while maintaining efficient oil production.

As explained in Bello et al. (2023)12, foam mechanisms for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration can be categorized into three main groups: gas trapping, gravitational segregation reduction, and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) leakage pathway blockage. Gas trapping involves the liquid phase within the foam effectively capturing gas through mechanisms such as snap-off, bypassing, and the Jamin effect. The Jamin effect occurs in foams within porous media, where fluid displacement leads to the formation of isolated pockets or bubbles of the displaced fluid46,47. These mechanisms are crucial for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration in depleted oil formations, and can readily occur during foam flow in porous media due to the fact that foams possess properties that make them conducive for gas trapping such as their variously sized gas bubbles that are sparged throughout a continuous liquid phase. Also, the wetting phase fills the small pores, leaving minimal space for gas bubbles in the non-wetting phase, meaning that they can occupy the center of the large pores.

Contribution of each trapping mechanism

To address the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage mechanisms in the reservoir, in our model, we simulated and included functions for residual, solubility, and mineral trapping mechanisms. The \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping efficiencies of the injection mechanisms are presented in Fig. 7.

Generally, we see that the trapping performance of gas injection is much lower than in foam injection. The higher trapping of the foam SAG injection could also be attributed to the ability of foam to reduce gas mobility in the reservoir.

Solubility trapping involves the dissolution of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into the formation water, which is a function of the interaction of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) with the brine. The SAG process enhances this interaction by creating a larger interface between the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) and the brine due to the structure of the foam that is generated. The surfactants in the foam can function as co-solvents, potentially increasing the solubility of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the brine. Additionally, the alternating injection of gas and surfactant solution can induce a mixing effect that promotes the dissolution of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) into the formation water, leading to more effective solubility trapping48. Similar results found in Adebayo (2019)47 and Lyu et al. (2021)19, were attributed to the ability of foam to control gas mobility and improve sweep efficiency.

Residual trapping is controlled by hysteresis. Hysteresis in capillary pressure and relative permeability can significantly affect the trapping of \(\text {CO}_{2}\). During the injection and subsequent imbibition cycles, the trapping characteristics of the reservoir can exhibit hysteresis, meaning that the drainage and imbibition curves do not coincide49,50. This hysteresis can lead to increased residual trapping because the capillary forces that allow \(\text {CO}_{2}\) to enter the pore spaces during injection are not the same as those that release it during imbibition. As a result, some \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is left trapped in the pore spaces after the injection process. During SAG injection, the foam generated can increase this hysteresis effect. In Adebayo (2018)51, the presence of the foam in the pore spaces of carbonate core samples altered the wettability and surface properties of the rock, which changed the capillary pressure relationships and enhanced the hysteresis effect, leading to more \(\text {CO}_{2}\) being residually trapped.

In Fig. 7c, we see that the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) mineralization was mainly due to dissolution of the minerals and not precipitation (negative vales denote dissolution, while positive values denote precipitation). It is interesting to see a significant increase (about 67%) in the mineralization trapping during the foam injection techniques. This further suggests that surfactant solutions can as well contribute to rock mineralization and further laboratory experiments are needed to assess that.

Table 5 below summarizes the potential of foam injection for oil recovery and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping.

The simulation results show the effectiveness of foam to increase the oil recovery factor than the continuous \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection technique in a carbonate reservoir. These findings further show that foam injection can improve oil recovery and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) trapping mechanisms, which promote \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration.

Notably, compared to the high residual trapping values, \(\text {CO}_{2}\) solubility trapping accounted for only 24.06% of the total trapping during SAG injection while during gas injection, solubility trapping was 20.68%. In Bello et al. (2024)23, we have shown how salinity causes a reduction in \(\text {CO}_{2}\) dissolution in brine, due to salting-out effects and an increase in aqueous viscosity. Hence, in such a high salinity reservoir like ours, such reduced \(\text {CO}_{2}\) solubility trapping efficiency is expected. The residual trapping was the most dominant in all cases and this could be attributed to the capillary forces existing within the reservoir from the residual oil. However, it is evident that solubility trapping would not be the most dominant mechanism in a high salinity, depleted oil reservoir.

Furthermore, the presence of surfactant reduces interfacial tension, allowing \(\text {CO}_{2}\) to spread more easily within the pore spaces and come into contact with more of the rock surface area. This increased contact enhances the likelihood of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) molecules being left behind as residual bubbles when the foam propagates. The foam has a higher apparent viscosity than the gas alone, which slows down the gas movement, allowing more time for the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) to be trapped by residual and solubility trapping47.

We also see very low mineralization trapping efficiencies for mineral trapping, corroborating results from previous studies concerning \(\text {CO}_{2}\) mineralization happening only after hundreds to thousands of years23,52,53. The effect of mineralization trapping is further shown in Fig. 8 where we see that all the three minerals simulated show a similar trend of dissolution over a simulation period of 100 years. Negative values signify the dissolution of the minerals. Fig. 8 shows the change in number of moles of the simulated minerals with time.

The dissolution process involves the reaction of the mineral with \(\text {CO}_{2}\) and water to form bicarbonate ions and cations of the mineral. The dissolution of calcite can be represented by the following reaction:

This reaction is driven by the acidity of the \(\text {CO}_{2}\)-saturated water, which increases the solubility of the calcite. Similar reactions can occur for dolomite, \((\textrm{CaMg}(\textrm{CO}_3)_2)\) and illite \((\textrm{KAl}_2(\text {Si}_3\textrm{Al})\text {AlO}_{10}(\text {OH})_2)\) as well, leading to the release of \(Mg^{2+}\), \(K^+\), and \(Al^{3+}\) ions into the solution.

In each of these reactions, the dissolution of minerals is favored under conditions where the concentration of dissolved \(\text {CO}_{2}\) and carbonic acid is high, leading to the formation of soluble bicarbonate ions and dissolved cations54. Thus, the preference for dissolution over precipitation in the presence of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) can be attributed to the thermodynamic stability of the dissolved species. As stated earlier, when \(\text {CO}_{2}\) dissolves into water, it forms carbonic acid, which dissociates into bicarbonate ions. The dissolution of minerals into bicarbonate ions represents a lower-energy state compared to the precipitation of minerals from the solution55. Furthermore, Johnston et al. (2021)56 reported that the precipitation of carbonate minerals is a much slower process than dissolution which can take hundreds to thousands of years. Therefore, it may not be observed during the timescale of 100 years as in our simulation.

Assessment metrics for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage in our model

To maximally achieve the purpose of CCUS strategies in the petroleum industry, it is important to co-optimize oil recovery with \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage. This helps to understand what to prioritize during field operations. Previous studies57,58 have introduced the concept of theoretical storage capacity. This refers to the quantity of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) that can be potentially stored in a porous medium and it assumes that the pore spaces previously occupied by the produced fluids can be potentially utilized for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage. The formula is presented below:

where \(M_t\) = theoretical \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage capacity in the porous medium, kg; \(\rho _{gas}\) = the density of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in reservoir conditions, kg/\(m^3\) ; RF = the recovery factor; A = the cross-sectional area of the porous medium, \(m^2\) ; h = reservoir thickness, m; \(\phi\) = porosity; \(V_{iw}\) = the volume of injected water, \(m^3\) ; \(V_{9w}\) = the volume of produced water, \(m^3\) ; \(S_{wi}\) = irreducible water saturation; \(C_{ws}\) = the solubility coefficient of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in formation water; and \(C_{os}\) = the solubility coefficient of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in oil.

Knowing \(M_t\), the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage efficiency can be calculated. Here, the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage efficiency is different from the percentage of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) retained in the reservoir which was earlier presented in Fig. 6. This rather refers to the efficiency of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) that can be stored in this particular reservoir. Different studies have assessed ways to calculate this, however, in Bello et al.12, we have included a modified formula that accounts for the \(\text {CO}_{2}\) loss due to surface and subsurface actions. When \(\text {CO}_{2}\) is injected, not all of it reaches the target sites. Some volume can be lost due to mechanical issues with the pumps, which may not operate at 100% efficiency. Additionally, some may escape through minor leaks in the injection system, including pipes, valves and fittings. Although in numerical studies, this is not expected to happen. We used a value of 5% for this59,60. The formula is presented below:

These assessment metrics were computed and the results are summarized in the Table 6 below:

From Table 6, it can be seen that foam can be used as a promising alternative to improve the storage capacity of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the reservoir. This amounts to an almost three-fold and eight-fold increase in storage capacity and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage efficiency, respectively.

Conclusions

This study presents findings from numerical simulations of foam in a hydrodynamic model that mimics a depleted oil formation with a residual oil saturation of 0.3. \(\text {CO}_{2}\) foam was injected with the dual purpose of enhanced oil recovery and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) Storage. Solubility, residual, and mineralization trapping mechanisms were modeled, and the results were analyzed. The main findings of this work can be summarized as follows:

-

Foam injection resulted in oil production at least 2.3 times higher than gas injection. This increase is due to significant \(\text {CO}_{2}\) spreading and enhanced volumetric sweep efficiency. Gas injection primarily channels through the oil zone, leaving significant oil unproduced, while foam mitigates this by enhancing viscosity and controlling gas mobility.

-

After 20 years, at the end of the production period with \(\text {CO}_{2}\) injection, only 25.68% of the injected \(\text {CO}_{2}\) remained in the reservoir, whereas with foam injection, 50.34% was retained.

-

During foam injection, the theoretical storage capacity of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) was increased by 2.6 times, presenting a potential to store 1.95 gigatonnes of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in the hydrodynamic model simulated.

-

Foam mechanisms for \(\text {CO}_{2}\) sequestration in a depleted oil reservoir include gas trapping, gravitational segregation reduction, and \(\text {CO}_{2}\) leakage pathway blockage.

-

The residual trapping mechanism accounted for over 70% of the total trapped \(\text {CO}_{2}\), making it the predominant trapping mechanism. Meanwhile, solubility trapping was significantly affected by the high salinity of the brine, resulting in only approximately 20% of the total \(\text {CO}_{2}\) being trapped.

-

The low efficiency of mineral trapping could be attributed to the relatively short simulation duration of 100 years. Efficient \(\text {CO}_{2}\) mineralization processes typically require hundreds to thousands of years to occur.

-

There was a 67% increase in mineralization trapping during foam injection compared to gas injection, indicating the significant contribution of surfactants. Further experimental studies should be conducted to investigate the impact of surfactants on rock mineralization.

With underground \(\text {CO}_{2}\) storage increasingly becoming a vital strategy in mitigating climate change by reducing atmospheric \(\text {CO}_{2}\) levels, foam injection techniques can potentially be optimized and adapted for various types of geological formations beyond depleted oil reservoirs. Furthermore, future works can focus on the long-term behavior of \(\text {CO}_{2}\) in these reservoirs, particularly on enhancing mineral trapping mechanisms which require longer periods to become effective. Additionally, a comprehensive assessments of the economic viability and environmental impacts of large-scale foam injection projects should be conducted to ensure that they are sustainable and cost-effective.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Decroocq, D. Energy conservation and CO2 emissions in the processing and use of oil and gas. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 58, 331–342. https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:2003020 (2003).

Lancon, O. & Hascakir, B. Contribution of oil and gas production in the us to the climate change. In Day 3 Wed, September 26, 2018, 18ATCE, https://doi.org/10.2118/191482-ms (SPE, 2018).

IEA. Emissions from Oil and Gas Operations in Net Zero Transitions - Analysis - IEA — iea.org. https://www.iea.org/reports/emissions-from-oil-and-gas-operations-in-net-zero-transitions (2023). [Accessed 12-04-2024].

PwC. How the oil and gas industry can turn climate-change ambition into action — strategyand.pwc.com. https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/m1/en/strategic-foresight/sector-strategies/energy-chemical-utility-management/climate-change-ambition.html (2021). [Accessed 15-04-2024].

Islam, R., Sohel, R. N. & Hasan, F. Role of oil and gas industry in meeting climate goals through carbon capture, storage and utilization CCUS. In Day 1 Tue, April 26, 2022, 22WRM, https://doi.org/10.2118/209311-ms (SPE, 2022).

Andersen, P. O. et al. Carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) in tight gas and oil reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 81, 103458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103458 (2020).

Bello, A., Ivanova, A. & Cheremisin, A. Foam EOR as an optimization technique for gas EOR: A comprehensive review of laboratory and field implementations. Energies 16, 972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020972 (2023).

Talebi, A., Hasan-Zadeh, A., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Riazi, M. A review on the application of carbonated water injection for EOR purposes: Opportunities and challenges. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 214, 110481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110481 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Innovative zoning control techniques for optimizing a megaton-scale CCUS-EOR project with large-pore-volume CO2 flooding. Energy Fuels 38, 2910–2928. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c04913 (2024).

Dorhjie, D. B. et al. The underlying mechanisms that influence the flow of gas-condensates in porous medium: A review. Gas Sci. Eng. 122, 205204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2023.205204 (2024).

Kumar, N., Augusto Sampaio, M., Ojha, K., Hoteit, H. & Mandal, A. Fundamental aspects, mechanisms and emerging possibilities of CO2 miscible flooding in enhanced oil recovery: A review. Fuel 330, 125633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125633 (2022).

Bello, A., Ivanova, A. & Cheremisin, A. A comprehensive review of the role of CO2 foam EOR in the reduction of carbon footprint in the petroleum industry. Energies 16, 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031167 (2023).

Chen, P., Bose, S., Selveindran, A. & Thakur, G. Application of CCUS in India: Designing a CO2 EOR and storage pilot in a mature field. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 124, 103858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2023.103858 (2023).

Oppert, S., Adachi, J., Thornton, D. & Royle, A. Monitoring technology to enable characterization of ccus reservoirs. In Second International Meeting for Applied Geoscience and Energy, https://doi.org/10.1190/image2022-w13-01.1 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists and American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 2022).

Amirlatifi, A., Ovalle, A., Bakhtiari Ramezani, S., Mohamed, I. & Abou-Sayed, O. General considerations for the use of offshore depleted reservoirs for CO2 sequestration. In Day 1 Mon, October 03, 2022, 22ATCE, https://doi.org/10.2118/210059-ms (SPE, 2022).

Hong, W. Y. A techno-economic review on carbon capture, utilisation and storage systems for achieving a net-zero CO2 emissions future. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 3, 100044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccst.2022.100044 (2022).

Callas, C. et al. Criteria and workflow for selecting depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs for carbon storage. Appl. Energy 324, 119668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119668 (2022).

Foyen, T., Brattekås, B., Fernø, M., Barrabino, A. & Holt, T. Increased CO2 storage capacity using CO2-foam. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 96, 103016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103016 (2020).

Lyu, X., Voskov, D. & Rossen, W. R. Numerical investigations of foam-assisted CO2 storage in saline aquifers. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 108, 103314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103314 (2021).

Alcorn, Z. P. et al. Pore- and core-scale insights of nanoparticle-stabilized foam for CO2-enhanced oil recovery. Nanomaterials 10, 1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10101917 (2020).

Bello, A. et al. An experimental study of foam-oil interactions for nonionic-based binary surfactant systems under high salinity conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 12208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62610-1 (2024).

Chaturvedi, K. R. & Sharma, T. In-situ formulation of pickering CO2 foam for enhanced oil recovery and improved carbon storage in sandstone formation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 235, 116484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2021.116484 (2021).

Bello, A., Dorhjie, D. B., Ivanova, A. & Cheremisin, A. Numerical sensitivity analysis of CO2 mineralization trapping mechanisms in a deep saline aquifer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 283, 119335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.119335 (2024).

Wu, H., Jayne, R. S., Bodnar, R. J. & Pollyea, R. M. Simulation of CO2 mineral trapping and permeability alteration in fractured basalt: Implications for geologic carbon sequestration in mafic reservoirs. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 109, 103383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103383 (2021).

Mouallem, J., Arif, M. & Mahmoud, M. Numerical simulation of CO2 mineral trapping potential of carbonate rocks. In Day 2 Tue, March 14, 2023, 23GOTS, https://doi.org/10.2118/214162-ms (SPE, 2023).

Postma, T. J. W., Bandilla, K. W., Peters, C. A. & Celia, M. A. Field-scale modeling of CO2 mineral trapping in reactive rocks: A vertically integrated approach. Water Resources Research58, e2021WR030626. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021wr030626 (2022).

Khandoozi, S., Hazlett, R. & Fustic, M. A critical review of CO2 mineral trapping in sedimentary reservoirs - from theory to application: Pertinent parameters, acceleration methods and evaluation workflow. Earth Sci. Rev. 244, 104515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104515 (2023).

Navier, C.-L. Navier Stokes Equation (Chez Carilian-Goeury, Paris, 1838).

Dorhjie, D. B. et al. Deviation from Darcy Law in Porous Media Due to Reverse Osmosis: Pore-Scale Approach. Energies. 15(18), 6656. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15186656 (2022).

Brown, G. O. The history of the darcy-weisbach equation for pipe flow resistance. In Environmental and Water Resources Historyhttps://doi.org/10.1061/40650(2003)4 (American Society of Civil Engineers 2002).

Dorhjie, D. B. et al. A Microfluidic and Numerical Analysis of Non-equilibrium Phase Behavior of Gas Condensates. Sci. Rep. 14, 9500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59972-x (2024).

Wang, Y., Vuik, C. & Hajibeygi, H. CO2 storage in deep saline aquifers: Impacts of fractures on hydrodynamic trapping. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 113, 103552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103552 (2022).

Joodaki, S. et al. Model analysis of CO2 residual trapping from single-well push pull test—Heletz, residual trapping experiment II. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 101, 103134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103134 (2020).

Land, C. S. Calculation of imbibition relative permeability for two- and three-phase flow from rock properties. Soc. Petrol. Eng. J. 8, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.2118/1942-pa (1968).

Holtz, M. H. Residual gas saturation to aquifer influx: A calculation method for 3-d computer reservoir model construction. In All Days, 02GTS, https://doi.org/10.2118/75502-ms (SPE, 2002).

Kumar, A. et al. Reservoir simulation of CO2 storage in deep saline aquifers. SPE J. 10, 336–348. https://doi.org/10.2118/89343-pa (2005).

Svensson, U. & Dreybrodt, W. Dissolution kinetics of natural calcite minerals in CO2-water systems approaching calcite equilibrium. Chem. Geol. 100, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(92)90106-f (1992).

Manual, C. U. Computer Modeling Group Ltd (Calgary, 2021).

Nghiem, L. X. & Li, Y.-K. Computation of multiphase equilibrium phenomena with an equation of state. Fluid Phase Equilib. 17, 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-3812(84)80013-8 (1984).

Bello, A. et al. An experimental study of high-pressure microscopy and enhanced oil recovery with nanoparticle-stabilised foams in carbonate oil reservoir. Energies 16, 5120. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16135120 (2023).

Fan, L. et al. Simulation on effects of injection parameters on CO2 enhanced gas recovery in a heterogeneous natural gas reservoir. Advanced Theory and Simulations4, 2100127.https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.202100127 (2021).

Al-Hashami, A., Ren, S. R. & Tohidi, B. CO2 injection for enhanced gas recovery and geo-storage: Reservoir simulation and economics. In All Days, 05EURO, https://doi.org/10.2118/94129-ms (SPE, 2005).

Li, Z. M., Zhang, C., Li, S. Y., Zhang, D. & Wang, S. H. Injection mode of CO2; displacement in heavy oil reservoirs. Adva. Mater. Res. 402, 680–686. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.402.680 (2011).

Bello, A. et al. Numerical study of the mechanisms of nano-assisted foam flooding in porous media as an alternative to gas flooding. Heliyon 10, e26689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26689 (2024).

Zoeir, A., Simjoo, M., Chahardowli, M. & Hosseini-Nasab, M. Foam EOR performance in homogeneous porous media: simulation versus experiments. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 2045–2054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-00845-0 (2020).

Wen, Y. et al. Molecular dynamics and experimental study of the effect of pressure on CO2 foam stability and its effect on the sequestration capacity of CO2 in saline aquifer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 284, 119518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.119518 (2024).

Adebayo, A. R. Sequential storage and in-situ tracking of gas in geological formations by a systematic and cyclic foam injection: A useful application for mitigating leakage risk during gas injection. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 62, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2018.11.024 (2019).

Ghosh, P. & Mohanty, K. K. Study of surfactant alternating gas injection (SAG) in gas-flooded oil-wet, low permeability carbonate rocks. Fuel 251, 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.03.119 (2019).

Ruprecht, C., Pini, R., Falta, R., Benson, S. & Murdoch, L. Hysteretic trapping and relative permeability of CO2 in sandstone at reservoir conditions. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 27, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2014.05.003 (2014).

Sedaghatinasab, R., Kord, S., Moghadasi, J. & Soleymanzadeh, A. Relative permeability hysteresis and capillary trapping during CO2 EOR and sequestration. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 106, 103262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103262 (2021).

Adebayo, A. R. Viability of foam to enhance capillary trapping of CO2 in saline aquifers-an experimental investigation. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 78, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2018.08.003 (2018).

Zhang, S. & DePaolo, D. J. Rates of CO2 mineralization in geological carbon storage. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2075–2084. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00334 (2017).

Daval, D. Carbon dioxide sequestration through silicate degradation and carbon mineralisation: promises and uncertainties. npj Mater. Degrad.2, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0035-4 (2018).

Xiao, N., Li, S. & Lin, M. Experimental investigation of CO2-water-rock interactions during CO2 flooding in carbonate reservoir. Open J. Yangtze Oil Gas 02, 108–124. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojogas.2017.22008 (2017).

Wilke, F. D., Vásquez, M., Wiersberg, T., Naumann, R. & Erzinger, J. On the interaction of pure and impure supercritical CO2 with rock forming minerals in saline aquifers: An experimental geochemical approach. Appl. Geochem. 27, 1615–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2012.04.012 (2012).

Johnston, V., Košir, A. & Martín Pérez, A. Evaluating carbonate dissolution and precipitation in a short time-frame using sem: techniques and preliminary results from postojna cave, slovenia. Acta Carsol.50, 253–267. https://doi.org/10.3986/ac.v50i2-3.9788 (2021).

Calvo, R. & Gvirtzman, Z. Assessment of CO2 storage capacity in southern Israel. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 14, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.12.027 (2013).

De Silva, P., Ranjith, P. & Choi, S. A study of methodologies for CO2 storage capacity estimation of coal. Fuel 91, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.07.010 (2012).

Cailly, B. et al. Geological storage of CO2: A state-of-the-art of injection processes and technologies. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 60, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:2005034 (2005).

Kelemen, P., Benson, S. M., Pilorgé, H., Psarras, P. & Wilcox, J. An overview of the status and challenges of CO2 storage in minerals and geological formations. Front. Climate1, 482595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2019.00009 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation under agreement no. 075-10-2022-011 within the framework of the development program for a world-class Research Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. D.B.D.: Methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, supervision. A.I.: Methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision. A.C.: Writing—review and editing, resources, project administration, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bello, A., Dorhjie, D.B., Ivanova, A. et al. A numerical feasibility study of CO2 foam for carbon utilization and storage in a depleted, high salinity, carbonate oil reservoir. Sci Rep 14, 20585 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70122-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70122-1