Abstract

Most published prediction models for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) were poorly reported, at high risk of bias, and heterogeneous in model performance. To tackle methodological challenges faced in previous prediction studies, we investigated whether model updating and extending improves mortality prediction, using the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) as a proxy. All COVID-19 patients admitted to seven ICUs in the Euregio-Meuse Rhine during the first pandemic wave were included. The 4C Mortality and SEIMC scores were selected as promising prognostic models from an external validation study. Five predictors could be estimated based on cohort size. TRIPOD guidelines were followed and logistic regression analyses with the linear predictor, APACHE II score, and country were performed. Bootstrapping with backward selection was applied to select variables for the final model. Additionally, shrinkage was performed. Model discrimination was displayed as optimism-corrected areas under the ROC curve and calibration by calibration slopes and plots. The mortality rate of the 551 included patients was 36%. Discrimination of the 4C Mortality and SEIMC scores increased from 0.70 to 0.74 and 0.70 to 0.73 and calibration plots improved compared to the original models after updating and extending. Mortality prediction can be improved after updating and extending of promising models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been a high demand for prediction models to support clinical decision-making. Especially in intensive care, capacity was severely strained, and the hope was that prediction models could assist in decision-making1,2. Many prediction models for the diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19 patients have been developed. All published diagnostic and prognostic models for COVID-19 were reviewed and were mostly at high risk of bias and poorly reported3. These methodological shortcomings could lead to overestimated model performance and, consequently, unreliable predictions that could cause harm when decisions are based on these numbers. A large individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis that externally validated promising prognostic models showed that model performance varied strongly and there was substantial between cluster heterogeneity4. These methodological challenges have been identified accompanied by recommendations for future prediction research, among which model updating and extending of available prediction models using data from multiple countries and healthcare systems3,4. Updating and extending, also often referred to as recalibration and redesign, mean that the linear predictor (LP) of the original model is recalibrated (other regression coefficient) and that additional variables can be added to the score, e.g. a country variable5,6,7.

Prior research on prediction modeling mainly focused on developing new models in each individual cohort rather than updating and extending promising existing models. Existing models tended to be rejected because of poor model quality or performance, so new ones were developed. This typically occurred in small datasets, particularly early in the pandemic3. Unfortunately, the same pattern then reoccurs, leading to many prediction models with limited generalizability that should be discouraged from being applied in daily patient care. However, all those rejected models contain predictive information that is valuable to a certain degree. For that reason, it seems beneficial to update and extend existing models resulting in models based on more evidence from more studies and, thus, more individuals. Hence, models are less overfitted, and performance in a new setting could be improved, while requiring less data5,6,7. Appropriate validation of these models will lead to more accurate predictions and better comparison between studies. Eventually, this could help healthcare providers with decision-making in daily patient care and healthcare policy, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Can outcome prediction in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) population be improved taking all the important methodological considerations3 and the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD)8 guideline into account? In this study, we therefore aim to show a complete and comprehensive method on how updating and extending of existing models can be performed. We choose a moderate-size multinational cohort of ICU patients early during the pandemic to show how to deal with moderate cohort size and a different setting than the developmental model cohorts, and used early pandemic data, as many new models were developed then, while updating was rare3. We hypothesize that model performance after updating and extending increases in the ICU setting. The multiregional ICU cohort will be used as an example, since there continues to be a lack of high-quality prognostic prediction models for the ICU setting nowadays9. The objective is to investigate whether mortality prediction by the 4C Mortality score and Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC), two models that showed reasonable model performance in a previous external validation study, can be further improved by model updating and extending9,10,11.

Results

Cohort

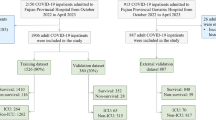

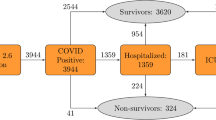

In total, 551 patients with COVID-19 were admitted to seven ICUs within the Euregio Meuse-Rhine from March 2 to August 12, 2020 (Fig. 1). The median age of the cohort was 67 [15] years, and 29% were female (Table 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, risk scores, and vital signs are shown in Table 1.

Outcomes

In the full cohort, 196 (36%) patients were deceased in the ICU (Table 1). From 27 (5%) patients, survival status remained unknown after contacting the centers where patients had been transferred to.

Predictors

Definitions, methods of measurement and missing values of all included predictors are described in Supplementary Table S1. The percentage of missing values for the predictors included in the updated and extended 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score varied from 0 to 18.1%.

The 4C Mortality score updating and extending

Logistic regression analyses were performed to update and extend the 4C Mortality score (Table 2). No predictors were excluded from the final model after bootstrapping with backward selection. The RCS function was thus included, meaning that the LP has a non-linear effect on survival (on the logit scale) in the ICU. Additionally, after accounting for the 4C Mortality score, a higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and being in a Dutch or German hospital increase mortality risks (Table 2).

SEIMC score updating and extending

Again, bootstrapping with backward selection did not result in exclusion of predictors from the final model indicating that the RCS function should be included in the final model. An increased SEIMC score leads to a higher mortality risk (Table 2). After adjustment for the SEIMC score, higher APACHE II scores and being admitted to a Dutch or German hospital also increase mortality risk.

Performance

Internal validation using bootstrapping yielded optimism-corrected areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of 0.74 and 0.73 for the 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score, respectively (Table 3).

Pooled calibration slopes for the updated and extended 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score were 0.97 and 0.96, respectively (Table 3). For both scores, the line in the flexible calibration plots closely approximates the diagonal with only slight under- and overestimation (Fig. 2).

Calibration plots of the original compared to the updated and extended scores. The predicted probability of mortality is reported on the x-axis and the actual (observed) probability on the y-axis. The diagonal reflects optimal calibration and above the x-axis, histograms of predicted risk are illustrated for patients who died and survived in the ICU. In addition, 95% confidence boundaries are shown by the grey area.

Shrinkage

To correct for overfitting, the beta regression coefficients reported in Table 2 were shrunken. Definitive beta regression coefficients of the updated and extended 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Comparison updated and extended models with original models

To compare the performance of the updated and extended 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score with the original ‘crude’ models, the areas under the ROC curve and calibration plots of this study were compared with external validation results in the EICC cohort9. The areas under the ROC curve from the 4C Mortality score increased from 0.70 to 0.74 after updating and extending (Supplementary Table S3). The area under the ROC curve rose from 0.70 to 0.73 after updating and extending the SEIMC score. Flexible calibration curves of the updated and extended 4C Mortality and SEIMC scores approached the 45 degrees diagonal more than the original scores (Fig. 2). For both scores, less underestimation in the lower predicted risks and less overestimation in the higher predicted risks was observed compared to the original model (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this study, we were able to improve model discrimination and calibration by means of updating and extending of two promising prediction models in the ICU. While previous studies continuously focused on developing new models resulting in poor external validation results, we are the first that demonstrate that updating and extending of available models improve mortality prediction. Eventually, this approach could lead to better prediction models that bring us one step closer towards clinical implementation.

To date, many prognostic prediction models have been developed for COVID-19, but almost none focused on model updating and extending. A study in Japan with 160 non-ICU patients investigated the external validity of four prediction models that predicted respiratory support and death12. They found that these prediction models overestimated the presence of the outcome event, which improved after recalibration. The model extended with non-routinely available urinary β2-microglobulin (β2MG) did not improve model performance. We used available ICU data that are clinically relevant to accomplish models with the best implementation in clinical practice. Elmoheen et al. externally validated the CURB-65 and pneumonia severity index (PSI) in 1181 COVID-19 patients admitted to a hospital in Qatar13. They demonstrated improved discrimination for the PSI model and better calibration for both scores after recalibration. Recently, a large international IPD meta-analysis that externally validated the most promising COVID-19 prediction models showed that performance of prognostic models was heterogeneous across countries and that local and dynamic adjustments of promising models are required before clinical implementation4. We attempted to show how this could be achieved.

As recommended, it is important to compare the target setting and population to those from the original model to reveal possible sources of heterogeneity3. The 4C Mortality score development and validation cohort were considerably larger than the EICC cohort and comprised a population that presented at hospital admission10. Patients were included during the same pandemic wave. Baseline characteristics differed moderately, whereas mortality rates were comparable9,14. Similarly, the SEIMC cohort comprised first pandemic wave patients11. The cohort size was larger than the EICC cohort. Baseline characteristics varied, and mortality rates were lower in the SEIMC cohort compared to the EICC cohort9,14. Both scores were primarily developed in hospitalized patients instead of ICU patients, which indicates that patients in the EICC cohort were at more advanced disease stages or had more severe illnesses, indicating another setting. Additionally, patient selection likely plays a role in the ICU, especially in a pandemic when resources are limited. The EICC cohort reflects a different, more homogeneous case-mix than the general ward population resulting in worse discrimination in the former setting6,7. To adjust for this case-mix difference, the APACHE II score, an important disease severity prediction score for the ICU population, and country variables to correct for data complexity were added to the original models14.

The main objective of the present study was not the deliver a valid COVID-19 prediction model for clinical practice in the ICU. Instead, we proposed a step-by-step approach to show model updating and extending of existing models according to the highest methodological standards taking a moderate cohort size into account15. Although, the COVID-19 ICU population was used as a proxy, this method could be applied to any other patient population following the TRIPOD guideline and recommendations by experts accurately3,8. The EICC dataset is representative for the ICU setting and includes patients from various healthcare systems and countries, improving understanding of generalizability and implementation across different settings and populations3. We show that model updating and extending can take the complexity in data structure into account by appropriately adding countries. We consider this essential in our heterogeneous EICC cohort14. Importantly, the research proposal and analyses were performed by a multinational and multidisciplinary team. With regard to the analyses, multiple imputation to appropriately handle missing data, pooling of parameter estimates and performance measures, adding restricted cubic splines to examine non-linearity, bootstrapping, backward selection and multiple imputation in each bootstrap sample to assess optimism, and shrinkage to correct for overfitting were performed. Finally, not only discrimination, but also calibration was shown by flexible calibration curves and calibration slopes, as appropriate.

We were limited by cohort size as our moderate cohort was sufficient for the prediction of only five predictors. Consequently, the individual predictors of the 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score could not be re-estimated separately. Nevertheless, we show that a LP, which was recalibrated as a reflection of the individual model predictors, leaves the opportunity to estimate two additional predictors. It is likely that model performance after updating and extending has improved by adding country as a factor due to heterogeneity within the EICC cohort. However, this heterogeneity highlights the importance of updating models to a new setting. The outcome status of 27 patients could not be retrieved after transport. Since these patients were classified as survivors, ICU mortality could have been underestimated. No external validation dataset was currently available to validate the updated and extended models. As a result, these findings could not be generalized to patients admitted later during the pandemic and patients admitted in the future. If our intention was to improve this model for application in clinical practice, external validation, updating of these adjusted models in other pandemic waves, and impact studies are essential additional steps before clinical implementation would be possible. Figure 3 shows the framework of the prediction process, demonstrating how updating and extending are integrated into this process (Fig. 3, Box). This requires more real time data for updating and extending during a pandemic, as the pandemic evolved faster than updating and extending were possible. In fact, this study has been overtaken by time as current virus variants differ from those in 2020 and stress on healthcare systems is considerably less than during the first pandemic wave. However, this study aimed to make a case against a focus on developing new prediction models on separate datasets as was done during the pandemic3.

This approach of prediction model updating and extending is beneficial and could be applied to any available or future risk score in any setting. It provides the opportunity to increase the potential of a model that has originally been developed for as specific patient group and period, as it can be continuously updated across different settings and over time and enriched with new variables or simplified instead. This leads to more reliable and sustainable prediction models, that have increased potential for clinical implementation. Updating and extending increase efficiency because predictive information from several studies is combined, predictive performance is improved, generalizability is increased, and bias is reduced. In future pandemics or when the prediction of patients’ outcomes is vital, better prediction of patients’ outcomes could be realized by reviewing available literature, external validation of available prediction models, and updating and extending of these models, taking these steps into account. The data density in the ICU, combined with complicated patients’ diseases, set the stage for more advanced regression and machine-learning techniques that consider dynamic and temporal predictor trends16.

Research population

As it was recommended to perform updating in individual patient data from multiple countries and healthcare systems3, we used the Euregio Intensive Care Covid (EICC) cohort to address our research question. This retrospective cohort is part of the Interreg Covid Data Platform (CoDaP) project and includes seven ICU departments in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine that collaborated on COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave. The seven participating departments include the Intensive Care Medicine departments of Maastricht University Medical Center + (MUMC +, Maastricht, the Netherlands), Zuyderland Hospital (Heerlen/Sittard, the Netherlands), VieCuri Hospital (Venlo, the Netherlands), Laurentius Hospital (Roermond, the Netherlands), Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg (Genk, Belgium), Jessa Hospital (Hasselt, Belgium), and University Hospital Rheinisch-Westfälische Hochschule (RWTH) Aachen (Aachen, Germany). All patients with confirmed COVID-19 and respiratory failure admitted to the ICU of any of the abovementioned hospitals were consecutively included between March 2 and August 12, 2020. COVID-19 diagnosis was based on either virus detection with polymerase chain reaction or a chest CT scan of 4–5 based on the COVID-19 Reporting and Data System (CO-RADS) score17. No exclusion criteria were set. Patients were admitted to the ICU via the emergency department, hospital ward, or transportation from other ICUs within or outside the Euregio because of tertiary care requirements or limited bed availability18. More detailed information on the cohort can be found in previous publications9,14,19.

Sample size calculation

Updating and extending can be done with varying degrees of complexity. The more complex the updating or extending strategy, the more data needed to execute it. The sample size for the EICC cohort was determined pragmatically. All patients were included since there was a desperate need for COVID-19 research during the first pandemic wave. For this research question, we calculated the number of predictors that could be estimated for model updating and extending purposes based on the available sample size. Unfortunately, little research has been conducted to determine adequate sample sizes for prediction model updating. Several rules of thumb are often used to estimate sample sizes for prediction model development studies6,7,15,20,21,22,23,24. However, Riley et al.15 stated that these are too simplistic and advocated that a more scientific approach that tailors sample size to the setting is required. Therefore, they developed a step-by-step guideline for sample size calculation in prediction models with binary outcomes, consisting of four separate steps, which were applied in this study. The lowest of the four sample size calculations per step was used to set the absolute number of predictors. Details of the sample size calculation are described in Supplementary File S5. To conclude, the pragmatic sample size of 551 patients was sufficient to estimate a model with a maximum of five predictors. As the available cohort size was insufficient to re-estimate all predictors included in the two original scores, the original LP was included as a predictor in the updated model, and one regression coefficient was estimated for the LP.

Model selection

Candidate prognostic models for model updating and extending were selected from a previous external validation study of COVID-19 models and established ICU prediction models in the EICC cohort9. Of all nine included and externally validated models, the 4C Mortality and SEIMC scores demonstrated the best discrimination and calibration and were selected for model updating and extending10,11. As recommended3, setting and model characteristics of the 4C Mortality and SEIMC scores have been detailed in Supplementary File S5.

Predictors

Early March 2020, a study protocol with certain demographic, anthropometric, vital, laboratory, and clinical variables was written and shared among the participating hospitals to construct the EICC cohort. In addition, numerous routinely available variables from admission to discharge were collected, among which the predictors included in the 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score. More information on collected predictors is outlined in Supplementary File S5.

Candidate predictors for model updating and extending

Target predictors for model updating and extending are predictors presumed to discriminate better in the target population and setting compared to the original model. ICU patients generally presented with more severe COVID-19 than ward patients. The established APACHE II25 score discriminates between severe and mild illness in ICU patients and was, therefore, one of the chosen predictors to enrich the 4C Mortality and SEIMC score. Furthermore, country was added as a categorical predictor to consider the multinational nature of the cohort since heterogeneity in the EICC cohort was observed previously14.

Outcomes

Patients were followed until the outcome occurred, either ICU death or ICU discharge to another hospital or the general hospital ward. These centers were contacted to retrieve the outcome status if patients were transported to other ICUs. If the outcome status remained unknown, patients were classified as survivors in the primary analyses with the potential risk of mortality underestimation.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM corporation, NY, USA) and R version 4.0.4 were used for the analyses. Data are presented as median [IQR] or percentages. Descriptive statistics were performed for the whole cohort. All patients were included in the analyses. Missing data were handled by multiple imputation if < 50% of values on a variable were missing; in other cases, variables were omitted from the analysis. Missing values were multiply imputed as documented elsewhere9,14,19,26. Continuous and categorical predictors were handled using the same definitions and cut-off values defined in the development study. For each patient, the LP (i.e., it summarizes the developed prediction model under investigation) was calculated by the intercept and sum of the models’ regression coefficients, reported in the 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score development studies, multiplied by the individual patient values10,11. The LP was then transformed into a probability score using the inverse logit transformation.

Different methods for model updating and extending exist5,6,7. As the sample size was sufficient for estimating a maximum of five predictors for each prognostic prediction model, a combination of model recalibration and extending was performed instead of re-estimating all predictors in the model. Therefore, for each model, the model intercept and estimated slope of the LP were updated. Additionally, the APACHE II score and a country factor were added to extend the updated models. The Belgian country part functioned as a reference group. A logistic regression model was fitted for the 4C Mortality score and SEIMC score with the LP, APACHE II score, Dutch country category and German country category included as model predictors, and ICU mortality as the outcome. Finally, parameter estimates of the individual imputed sets were pooled using the total covariance matrix pooling27.

In order to examine non-linear effects in the linear predictor, a restricted cubic spline (RCS) function with three knots for the LP was added to the model. Bootstrapping with backward selection using the Prediction Model Pooling, Selection and Performance Evaluation Across Multiply Imputed Datasets (psfmi) package was performed to determine whether the RCS function should be included in the model. A p-value less than 0.1 was considered to be statistically significant, advocating the inclusion of the RCS function in the final model27. After the updated and extended models had been fitted, bootstrapping was performed 200 times to validate the updated and extended models internally. To assess the optimism, multiple imputation and backward selection were repeated in each bootstrap sample with a p-value of 1.027. Model performance was examined by discrimination and calibration6,7,8,28,29. Model discrimination implies the ability of a prediction model to distinguish between patients who develop the outcome of interest and those who do not. This is reflected by the optimism-corrected area under the ROC curve obtained after bootstrapping. An area under the ROC curve of 1 represents ideal discrimination, whereas 0.5 represents no discrimination6,7. The second parameter, model calibration, refers to the correspondence between the observed outcome proportions and predicted outcome risk. This is illustrated by the calibration intercept, the calibration slope, and flexible calibration curves6,7,30. Ideally, the calibration intercept is 0 and the calibration slope is 1. The optimism-corrected calibration slope was retrieved after bootstrapping27. Flexible calibration curves using local regression were constructed for each updated and extended model and the original models6,7,10,11,23. To create these curves with a multiple imputed dataset, the mean LP of all multiple imputed sets was computed and used. The final step was the shrinkage of the regression coefficients towards zero to prevent overfitting. The beta regression coefficients from the updated and extended models were multiplied by the shrinkage factor based on the optimism-corrected calibration slope, resulting in shrunken regression coefficients6,7. Afterwards, the model intercept was re-estimated by logistic regression with the new LP as an offset variable.

Ethics approval

The medical ethics committee (Medisch Ethische Toetsingscommissie 2020–1565/3 00 523) of Maastricht UMC + provided ethical approval31. The study was conducted in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and national data privacy laws. Data sharing agreements were composed by legal officers of Maastricht UMC + and Clinical Trial Center Maastricht (CTCM), judged by the legal department of each hospital, tailored to each center, and then signed to ensure adequate and safe data sharing.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a stepwise approach to prediction model updating and extending and showed that updating and extending of two promising prognostic COVID-19 prediction models lead to improved mortality prediction in the ICU. Instead of developing new models on separate datasets done during the pandemic, this study makes a case towards clinical implementation of prediction models that requires various steps, from literature reviewing of developed models, extensive data collection, and external validation, to updating and extending the most promising models.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data sharing agreements of the participating hospitals. Individual patient data and the pseudo-anonymized dataset will not be made available to others. Only data for the full cohort or a particular subcohort will be published and shared after the provision of a research proposal and signed data access agreement of each participating hospital. Please contact the corresponding author (Daniek.meijs@mumc.nl) to request these data.

References

Ma, X. & Vervoort, D. Critical care capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic: Global availability of intensive care beds. J. Crit. Care 58, 96–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.04.012 (2020).

Douin, D. J. et al. ICU bed utilization during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic in a multistate analysis-March to June 2020. Crit. Care Explor. 3, e0361. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000361 (2021).

Wynants, L. et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: Systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 369, m1328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1328 (2020).

de Jong, V. M. T. et al. Clinical prediction models for mortality in patients with covid-19: External validation and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 378, e069881. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-069881 (2022).

Moons, K. G. et al. Risk prediction models: II. External validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart 98, 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301247 (2012).

Steyerberg, E. W. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating (Springer, 2019).

Steyerberg, E. W. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating (Springer, 2009).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0697 (2015).

Meijs, D. A. M. et al. Predicting COVID-19 prognosis in the ICU remained challenging: External validation in a multinational regional cohort. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 152, 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.10.015 (2022).

Knight, S. R. et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ 370, m3339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3339 (2020).

Berenguer, J. et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for 30-day mortality in hospitalised patients with COVID-19: The COVID-19 SEIMC score. Thorax 76, 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216001 (2021).

Yamada, G. et al. External validation and update of prediction models for unfavorable outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 27, 1043–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2021.04.008 (2021).

Elmoheen, A. et al. External validation and recalibration of the CURB-65 and PSI for predicting 30-Day mortality and critical care intervention in multiethnic patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 111, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.027 (2021).

Mesotten, D. et al. Differences and similarities among Coronavirus Disease 2019 patients treated in seven ICUs in three countries within one region: An observational cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 50, 595–606. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005314 (2022).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 368, m441. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m441 (2020).

Xie, J. et al. A review of modeling methods for predicting in-hospital mortality of patients in intensive care unit. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. https://doi.org/10.21037/JECCM.2017.08.03 (2017).

Prokop, M. et al. CO-RADS: A categorical CT assessment scheme for patients suspected of having COVID-19-definition and evaluation. Radiology 296, E97–E104. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020201473 (2020).

Strauch, U. et al. QUIT EMR trial: A prospective, observational, multicentre study to evaluate quality and 24 hours post-transport morbidity of interhospital transportation of critically ill patients: Study protocol. BMJ Open 7, e012861. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012861 (2017).

Meijs, D. A. M. et al. Better COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit survival in females, independent of age, disease severity, comorbidities, and treatment. Sci. Rep. 12, 734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04531-x (2022).

Collins, G. S., Ogundimu, E. O. & Altman, D. G. Sample size considerations for the external validation of a multivariable prognostic model: A resampling study. Stat. Med. 35, 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6787 (2016).

Harrell, F. E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis (Springer, 2015).

Snell, K. I. E. et al. External validation of clinical prediction models: Simulation-based sample size calculations were more reliable than rules-of-thumb. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 135, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.011 (2021).

Van Calster, B. et al. A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: From utopia to empirical data. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 74, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.005 (2016).

Vergouwe, Y., Steyerberg, E. W., Eijkemans, M. J. & Habbema, J. D. Substantial effective sample sizes were required for external validation studies of predictive logistic regression models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 58, 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.017 (2005).

Knaus, W. A., Draper, E. A., Wagner, D. P. & Zimmerman, J. E. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 13, 818–829 (1985).

White, I. R., Royston, P. & Wood, A. M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 30, 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4067 (2011).

Heymans, M. & Eekhout, I. psfmi: Prediction Model Pooling, Selection and Performance Evaluation Across Multiply Imputed Datasets. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psfmi/index.html. Accessed July 2022.

Debray, T. P. et al. Individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses of diagnostic and prognostic modeling studies: Guidance on their use. PLoS Med. 12, e1001886. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001886 (2015).

Riley, R. D. et al. External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: Opportunities and challenges. BMJ 353, i3140. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3140 (2016).

Van Calster, B. et al. Calibration: The Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 17, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1466-7 (2019).

Tas, J. et al. Serial measurements in COVID-19-induced acute respiratory disease to unravel heterogeneity of the disease course: Design of the Maastricht Intensive Care COVID cohort (MaastrICCht). BMJ Open. 10, e040175. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040175 (2020).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 (1987).

Funding

This work was supported by the "Interreg Euregio Meuse-Rhine" (Covid Data Platform (CoDaP) grant: Interreg-EMR 187). The funding source was not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing process, and decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization and study design: LW, SMJvK, BS, CIES, AH, JM-S, LJMS, JB, DM, ICCvdH, GM, BCTvB. Methodology: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, LJMS, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Software: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, LJMS, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Validation: DAMM, BCTvB, LW. Formal analysis: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, LJMS, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Investigation: DAMM, CIES, AH, JM-S, BS, JB, DM, BCTvB. Resources: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, CIES, AH, JM-S, BS, MvL, EGMC, JWEMS, LJMS, JB, DM, ICCvdH, GM, BCTvB, CoDaP investigators. Data curation: DAMM, LW, BCTvB, CoDaP investigators. Writing—original draft: DAMM, LW, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Writing—review & editing: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, CIES, AH, JM-S, BS, MvL, EGMC, JWEMS, LJMS, JB, DM, ICCvdH, GM, BCTvB, CoDaP investigators. Visualization: DAMM, LW, SMJvK, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Supervision: DAMM, LW, ICCvdH, BCTvB. Project administration: DAMM, BCTvB. Funding acquisition: BS, DM, ICCvdH, GM, BCTvB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meijs, D.A.M., Wynants, L., van Kuijk, S.M.J. et al. Boosting the accuracy of existing models by updating and extending: using a multicenter COVID-19 ICU cohort as a proxy. Sci Rep 14, 26344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70333-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70333-6