Abstract

This study addresses the question of the lateral preference of the National Hockey League players. The shooting preference, left or right, was analysed as a function of the origin of four groups of players that are from the USA, Canada, Europe, or Russia. The analysis reveals that the players from the USA are more likely to shoot right than players from other countries. Also, compared to defense players from other groups, defense players from the USA have a higher number of shots per game and a higher goal-to-assist ratio. The study also shows that for wingers shooting left, those playing on the right wing have more goals or points per game than those playing on the left wing; and that European forward players have a better differential (+/−) than American and Canadian forward players. The study reveals the influence of the players’ origin on the preference in a bimanual asymmetric task and the impact of this preference on ice hockey performances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article addresses the issue of lateral preference in bimanual sports. Typically, the representation of a lateral preference is based on the use of one hand instead of another for a task such as writing, throwing a ball, or holding a spoon. Depending on the criteria adopted to define hand preference, around 10–18% of people prefer using their left hand1,2,3, with males being more often ambidextrous or left-handers than females4. The overall picture is a little more blurred when eyedness, footedness, or bimanual tasks, instead of unimanual tasks, are considered to determine lateral preference5,6,7.

The case of lateral preference in sports requiring the contribution of both hands is less straightforward. While there is clear preference for batting right in baseball8,9, with about two Major League Baseball players out of three batting right during the 2016 season10, the case of ice hockey is a bit more intriguing. In a recent study conducted with (mainly) Canadian volunteers5, out of the 583 right-handers, 66.2% reported a preference for shooting left in ice hockey (i.e., placing the left hand in the middle of the stick), and 31.4% for shooting right (a few people reported no preference). Amongst the 131 left-handers of the study, 26.0% reported a preference for shooting left in ice hockey, and 70.2% for shooting right. These proportions for ice hockey went in the opposite direction in a German study11, and in a Spanish study involving children12, but in all cases, the prediction of the lateral preference in ice hockey based on unilateral tasks remained poor.

These different proportions in Canadian versus German lateral preferences for ice hockey indicate that there could be important cultural differences in the field. In the same vein, it has also been shown that right-handed Canadian-born players that reached the Major League Baseball (MLB) are more prone to bat left (i.e., standing on the right side of the home plate, from the catcher standpoint, with their right hand at the lower extremity of the bat) than players from other countries, namely, the USA, the Dominican Republic, and players from South Asia (Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea). Indeed, overall, the chances of batting left when you are throwing right is at least twice greater when you are Canadian than when you are from other regions10. This is a non negligible advantage considering that, in general, batting performances are better when batting left than batting right8,13. This particularity of Canadian baseball players is attributed to the fact that Canadian ice hockey players are much more likely, as indicated earlier, to shoot left than to shoot left10.

Studying laterality in ice hockey is even more relevant considering that the lateral preference has an incidence on the type of performances. For instance, amongst left wingers, those who shoot right tend to accumulate more points than those who shoot left; along the same line, amongst right wingers, those shooting left accumulate more points than those shooting right14. Other researchers have found that players shooting right is associated with scoring more goals, while shooting left is associated with obtaining more assists15. Additionally, during shootout, players shooting left have less success against goalkeepers catching right15.

The first purpose of the present study was to look at the effect of potential cultural differences in the lateral preference in ice hockey. Instead of looking at the effect of playing ice hockey in childhood on the batting preference in baseball10, we reversed the question, looking at a potential influence of baseball on the way of holding a hockey stick. Because baseball is very popular in the USA16 and because there are much more players batting right than batting left in baseball8,9,10, ice hockey players from the USA were expected be more likely to shoot right than players born in Canada. The contrast with European or Russian ice hockey players was expected to be even more important because baseball is not as popular in Europe and Russia as it is in North America. For instance, since 1933, only one MLB player was reported to be born in Russia and none from Sweden or Finland17. A second objective of this study was to determine whether shooting left or right has an incidence on different performance indicators. The performance analyses were applied to two groups, forward and defense players, and took the origin of players into account.

Method

Participants

For the distribution of lateral preferences, there were two rounds of analyses. In the first, data covered the whole history of the NHL (i.e., since its inception in 1917). In the second round, data of players since the 1967–1968 season were analysed.

There were four reasons why the first 50 seasons of the NHL were cut for the hockey statistics analyses: (1) the data were less reliable, (2) there were important fluctuations in the number of goals per game during that period, as indicated, for instance, by the fact that during the 1928–1929 season, Boston led the league with 89 goals in 44 games, and Chicago scored only 33 goals that year, (3) there was a period where there was a maximum of one assist per goal (now it is two), and (4) it was mostly in the 1970s that players from Europe arrived in the NHL, and around the end of the 1980s that Russian players (then USSR) came in the NHL. Also note that for the 1967–1968 season, the NHL moved from a 6-team league to a 12-team league.

Both rounds of analyses included only regular season games until the end of the 2022–2023 season. Moreover, in both rounds, players were grouped according to their origin: the USA, Canada, Europe, and Russia. Because a large part of Russia is in Asia, it was not included in Europe; also, Russian ice hockey has a very long tradition of excellence. No goalkeeper was kept in the sample.

For the part covering the whole history of the NHL, data of 7478 players were collected. There were 1265 Americans, 4805 Canadians, 1145 Europeans, and 263 Russians. A total of 73 players were not included because their shooting side was unavailable. There were 5042 and 2436 forward and defense players, respectively, 803 and 462 from the USA, 3308 and 1497 from Canada, 757 and 388 from Europe, and 174 and 88 from Russia.

For the part covering the period since the 1967–1968 season, data of 6385 players were collected. There were 1210 Americans, 3807 Canadians, 1107 Europeans, and 261 Russians. A total of 73 players were not included because their shooting side was unavailable. Most European players were coming from Sweden (n = 364), Finland, (n = 215), Czechia (n = 230), and Slovakia (n = 89). There were 4205 and 2107 forward and defense players, respectively, 762 and 434 from the USA, 2543 and 1205 from Canada, 727 and 380 from Europe, and 173 and 88 from Russia.

Skaters’ performance analyses were carried out on American, Canadian, European, and Russian players between the 1967–1968 and 2022–2023 regular seasons. In addition, were removed from the analyses skaters who failed to score at least one point and one goal, and skaters who played less than 82 games, i.e., the number of games in an NHL regular season since the 1995–1996 season. A total of 2667 players were excluded. Therefore, 672 Americans, 2237 Canadians, 629 Europeans and 141 Russians players were included in the analyses. There were 2456 and 1223 forward and defense players, respectively, 433 and 239 from the USA, 1520 and 717 from Canada, 408 and 221 from Europe, and 95 and 46 from Russia.

Material

The information about the players was drawn from the NHL official website (https://www.NHL.com/stats/skaters)18. Extracted data included lateral preference (left or right), origin, position (centre, left winger, right winger, defense player; there was no information about playing left or right on defense).

Performance indicators

Performance data were extracted including goals per game, assists per game, points per game, goal-to-assist ratio, penalty minutes per game, shots on goal per game, and + /− differential (in ice hockey, when teams are even strengths, a player on the ice is assigned + 1 when his team scores a goal, or − 1 when the opponent scores a goal).

Data analyses

All analyses were performed using R Project version 4.3.119 (ɑ = 0.05). For the distribution of lateral preferences, a chi-square (χ2) analysis was conducted. The distribution of each group (origin) was contrasted with the distribution of the overall population. This analysis was conducted with the data covering the history of the NHL and the data beginning with the 1967–1968 season. In addition, a chi-square analysis was conducted on the distribution of players adopting a “cross-lateral position”, i.e., players shooting left playing on the right wing versus players shooting right playing on the left wing. Finally, a chi-square analysis was conducted on cross-lateral positions between American and Canadian players together compared to European and Russian players together.

The analyses of hockey performances were based on the data beginning with the 1967–1968 season. For forward players, a 2 (Lateral preference) × 3 (Position) × 4 (Origin) ANOVA was conducted on each of the seven dependent variables. For defense players, a 2 (Lateral preference) × 4 (Origin) ANOVA was conducted on each dependent variable. Post hoc analyses were conducted using the Bonferroni multiple comparison method.

Results

Out of the 7478 players in the history of NHL, 63.28% were shooting left and 36.72% were shooting right. As indicated in Table 1, the proportion of players shooting right was higher for players from the USA than those from Canada, Europe, or Russia. Table 1 also shows the proportion of players shooting left or right in the four groups of the study since the 1967–1968 season, and the proportions were about the same.

A chi-square analysis on the data covering the NHL history revealed that the frequency of players shooting left or right in the USA was different from that in the overall NHL sample, with the number of players shooting right being significantly higher in the USA, χ2(1) = 57.96, p < 0.001. As well, a chi-square analysis revealed that the frequency of European players shooting left or right was different from that in the overall sample, with the number of players shooting left being higher, χ2(1) = 69.30, p < 0.001; the same results was found for Russian players, χ2(1) = 14.34, p < 0.001. Finally, the chi-square analysis applied to the Canadian data showed no significant effect.

Chi-square analyses on the data covering the period beginning with the 1967–1968 season showed the same results as those obtained for the history of the NHL. Firstly, the frequency of players shooting right was significantly greater in the USA than in the overall sample, χ2(1) = 64.45, p < 0.001. In addition, the frequency of players shooting left was significantly greater among Europeans, χ2(1) = 72.75, p < 0.001 and Russians, χ2(1) = 13.41, p < 0.001 than in the overall sample. Finally, no difference was observed between Canadians and the overall sample.

Table 2 shows the number of forward players shooting left or right, since the 1967–1968 season, at each position: centre, left wing, and right wing. This distribution was presented as a function of the origin of players. Amongst players adopting a “cross-lateral position”, there were much more players shooting left playing on the right wing than players shooting right playing on the left wing, χ2(1) = 103.14, p < 0.001. Also, players from Europe or from Russia were more likely to adopt a “cross-lateral position” than Canadian or American players, χ2(1) = 95.02, p < 0.001.

Performances—forward players

Table 3 showed the mean performances of each lateral preference and origin group as a function of position of forward players: left and right wingers and centres.

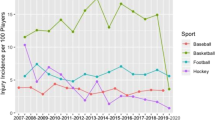

For the number of goals per game, the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of origin, F(3, 2432) = 4.334, p = 0.005, ƞ2 = 0.005; and note a trend for the position effect, F(2, 2432) = 2.668, p = 0.069, ƞ2 = 0.002. European and Russian players scored more goals per game than American players (Fig. 1A). The laterality × position interaction was significant, F(2, 2432) = 3.156, p = 0.043, ƞ2 = 0.003. All other effects were nonsignificant (ps ≥ 0.134). Post hoc analyses revealed that amongst players shooting left, right wingers had a higher number of goals per game than left wingers and centers (Fig. 2A).

(a) Number of goals per game, (b) of assists per game, (c) of points per game, and (d) differential as a function of players’ origin amongst forward players. USA United States of America (orange), CAN Canada (green), EUR Europe (blue), RUS Russia (purple). (data since the 1967–1968 season). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(a) Number of goals per game, (b) of assists per game, and (c) of points per game as a function of players’ position and shooting side amongst forward players. LW left wing, C center, RW right wing, P/S player shoots, L left (pink), R right (blue). (data since the 1967–1968 season). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

For the number of assists per game, the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of origin, F(3, 2432) = 5.916, p = 0.016, ƞ2 = 0.007, with European, Russian, and Canadian players having more assists per game than American players (Fig. 1B). The laterality × position interaction was significant, F(2, 2432) = 3.641, p = 0.026, ƞ2 = 0.003. All other effects were nonsignificant (ps > 0.192). Post hoc analyses revealed that amongst players shooting left, centers had a higher number of assists per game than left wingers (Fig. 2B); and note that right wingers also tended (p = 0.061) to have more assists that left wingers.

For the number of points per game, the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of origin, F(3, 2432) = 5.501, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.007, with European, Russian, and Canadian (p = 0.055) players having more points per game than American players (Fig. 1C). The laterality × position interaction was significant, F(2, 2432) = 3.728, p = 0.024, ƞ2 = 0.003. All other effects were nonsignificant (ps > 0.163). Post hoc analyses revealed that amongst players shooting left, right wingers had a higher number of points per game than left wingers (Fig. 2C).

For the goal-to-assist ratio, the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of position, F(2, 2432) = 6.998, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.006. All other effects were nonsignificant (p > 0.181). Post hoc analyses revealed that right wingers have a higher goal-to-assist ratio than left wingers and centers.

For the number of penalty minutes per game, the ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of origin, F(3, 2432) = 22.939, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.027. Post hoc analyses revealed that Canadian players had more penalty minutes per game than players from the other three groups, and American players had more penalty minutes per game than European players. Note the position effect (p = 0.057) and the position × origin interaction (p = 0.096). Centers tended to have less penalty minutes per game than wingers.

For the number of shots on goals per game, the picture was more complex. There were significant main effects for laterality, F(2, 2432) = 3.93, p = 0.048, ƞ2 = 0.002; position, F(2, 2432) = 4.73, p = 0.009, ƞ2 = 0.004; and origin, F(2, 2432) = 5.36, p = 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.006. Three interaction effects were significant: laterality × position, F(2, 2432) = 3.67, p = 0.026, ƞ2 = 0.003; laterality × origin, F(3, 2432) = 3.22, p = 0.022, ƞ2 = 0.004, and position × origin, F(6, 2432) = 2.22, p = 0.039, ƞ2 = 0.005. In addition to the fact that, overall, players shooting right had more shots on goal than players shooting left, the post hoc analyses indicated that right wingers had more shots on goal than centers, and Russian players had more shots on goal than Canadian and American players. Also, amongst players shooting left, right wingers had more shots on goal than left wingers and than centers. Moreover, Russians shooting right had more shots on goal than Americans shooting right or than Canadians shooting left; and Europeans shooting left had more shots on goal than Canadians shooting left. Finally, European right wingers had more shots on goal than Canadian right wingers, and more than Canadian and American centers.

For the differential statistic, the ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of origin, F(3, 2432) = 22.939, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.005. Post hoc analyses revealed that European players had a better differential than American and Canadian players (Fig. 1D). All other effects were nonsignificant (ps > 0.257).

Performances—defense players

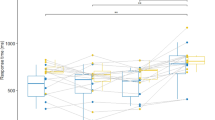

Table 4 shows the mean performances of each laterality and origin group for defense players.

For the number goals per game, points per game, and differential, the ANOVAs revealed no significant effects (ps ≥ 0.132). For the number of assists per game, note the origin effect, F(3, 1215) = 2.297, p = 0.076, ƞ2 = 0.006, with Russians tending to have had more assists per game than Canadians. For the penalty minutes per game, there was a significant origin effect, F(3, 1215) = 26.555, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.061. Canadians had more penalty minutes than Europeans (p < 0.001).

From a laterality viewpoint, the results with the next two dependent variables were more interesting. For the number of shots on goals per game, there was a significant effect of laterality, F(1, 1215) = 6.141, p = 0.013, ƞ2 = 0.005. Defense players shooting right had more shots on goal than defense players shooting left. For the goal-to-assist ratio, there was a significant laterality × origin effect, F(3, 1215) = 3.590, p = 0.013, ƞ2 = 0.009 (Fig. 3). Post hoc analyses revealed that Americans shooting right had a higher goal-to-assist ratio than Americans shooting left (p = 0.004).

Discussion

In the present study, there were two main objectives related to laterality in ice hockey. One was to reveal the distribution of players according to their lateral preference and origins, and the other was linked to the impact of this preference on performances.

The main finding in this study was related to the distribution of players shooting left versus players shooting right as a function of their origin. Clearly, there were much more players susceptible to shoot right when they were from the USA than when they were from anywhere else in the world. This observation applied to both analyses, the one involving the history of the NHL and the one limited to players since the 1967–1968 season.

Considering that, as far as we know, there was no reason to believe that the distribution of left- versus right-handed people is heavily different in the USA20 (around 10–13%) from that in the rest of the world2 (around 10,6%), it was reasonable to posit that the difference found for ice hockey was based on cultural differences. One such cultural difference could be the participation to other sport activities requiring the contribution of both hands. One very popular sport in the USA is baseball. This sport requires to use both hands in either one role or another when batting. Despite the advantage of batting left, close to 2 out of 3 righthanded players in baseball were batting right8,10. This cultural feature is a viable hypothesis to explain the lateral particularity of ice hockey players from the USA, just like the participation to ice hockey has been argued to have an impact on the batting lateral preference of Canadian born MLB players10. Somewhat along the same line, assuming that baseball is not as popular in Russia and Europe (where football/soccer is popular) than in Canada, it is not surprising to see that the proportion of players shooting right was slightly higher in Canada than in Europe or Russia.

The key finding that should be emphasized to understand the impact on performances of the lateral preference of the NHL American players could be found in the sample of defense players where no indication was given about the fact of playing on the left or right side on the ice. Overall, defense players shooting right had more shots on goal more often than defense players shooting left. Assuming that nearly 90% of players were righthanders for unimanual activities and given that American players were more likely to shoot right than other players, this means that more players were assigning their preferred hand in the middle of the hockey stick, which should favor a playing style based on force. Based on a study with young elite ice hockey players, players placing their preferred hand at the middle of the stick (righthanders shooting right or lefthanders shooting left) were more likely to play with force while players placing their preferred hand at the end of the stick (righthanders shooting left of lefthanders shooting right) were more likely to have a playing style based on finesse (stick handling)21. The fact that defense players shooting right had more shots on goal could be interpreted as an indication of a playing style based on force more than on finesse. A second significant dependent variable, this time involving specifically American defense players, was consistent with this interpretation. American defense players had a higher goal-to-assist ratio than players for other countries. It is reasonable to associate the fact of having more assists with a playing style based on finesse. The different distribution of defensemen shooting left or right in the USA, compared to defensemen from other countries, would then lead to a different playing style, based more on power than on finesse and, consequently, to an increased likelihood to shoot on goal and to have a higher goal-to-assist ratio.

The statistics of shots on goal of forward players were more complex. Overall, players shooting right had more shots on goal than players shooting left. Assuming that there were much more righthanders in the sample, it indicates that placing the nonpreferred hand at the middle of the stick led to a playing style closer to stickhandling (finesse) than shooting (exerting power). However, the global picture with forwards was complex because the specific position (centre, left wing, right wing) had an impact on the type of performances. For the goal-to-assist ratio dependent variable, there was a USA effect for defense players, but not for forwards. For forward players, the goal-to-assist ratio of centers was significantly lower that that of right wingers. This finding was not surprising given that centers are traditionally play makers in ice hockey, which results in a lower goal-to-assist ratio, a finding consistent with a playing style less based on finesse (play making). American forwards had a significantly lower number of assists per game than players from other countries; this finding also indicates that American players were less likely to adopt a playing style based on finesse.

So far, data from defense players were the most telling to analyse the impact of the lateral preference of American players. For the data of forward players, shooting side was important, but its effect was most often intertwined with the position on the ice, and the position adopted was susceptible to vary with the players’ origin.

In general, wingers having a cross-lateral preference had better performances. Because there were more players shooting left, more of them were moved on the right wing than the reverse (players shooting right playing left wing). It was amongst players shooting left that a significant difference could be found: right wingers had a higher number of goals per game and of points per game than left winger and tended to have a higher number of assists. This finding was consistent with previous data14. A part of the success of right wingers could be related to the fact that there were more centres shooting left than right; being on the right side of centres, right wingers were more likely to receive passes from that side (left wingers were on the backhand side of centres shooting left).

The specific success of right wingers shooting left could be attributed to the possibility of having a better angle for shooting on net than right wingers shooting right, and to the possibility to have a better view on the overall action on ice when the puck is on the “natural” side (not on the backhand). Also, it is much more difficult for a player shooting right, when playing right wing, to move around a defenseman (and “cut inside”) than it is for a player shooting left.

From a differential viewpoint, European forward players are better than American and Canadian players. Moreover, European and Russian players scored more goals and had more points per game than American players. It is difficult to sort out, with the present data, if the efficiency of right-wingers shooting left was due to the massive presence of non-North American players in this category, or if the success of European and Russian players was due to their inclination to adopt a cross-lateral preference. Note that a part of the success of European players may also rely partly on their discipline, as suggests the fact that their amount of penalty in minutes per game was lower than that of Canadian and American players.

Limitations and future studies

One major finding in the study was linked to the particular distribution of players shooting left versus right amongst NHL players from the USA. This finding was attributed to the participation to baseball during youth, a sport requiring the contribution of both hands on the bat and exhibiting a lateral preference. This explanation, based on the fact that a majority of players throwing right in baseball will bat right, remains speculative: American righthanders, if they bat right, would then be more inclined to shoot right when time comes to grab a stick to play ice hockey. The interpretation of the effect of the shooting stance of American NHL players assumed that most of them are right-handers for unimanual tasks. Indeed, we do not have the certainty that handedness for unilateral tasks is the same in the different countries. Based on the writing hand, there seems to be slightly more left-handers in Canada and in the USA than in Sweden, Finland, or Russia2.

Ideally in future studies, it would be most relevant to also assess the lateral preference for unimanual tasks of ice hockey players when studying their shooting preference and performances to determine more precisely who places the preferred hand in the middle of the stick and who does not. Moreover, it would probably be careful to test other aspects of lateral preferences, like eyedness or vestibular dominance, to understand who is the most apt to successfully adopt a cross-lateral preference when playing as a winger in ice hockey. Another limitation is related to the fact that forward positions in the study are those listed by the NHL, but forwards may change positions over the course of their career (e.g., switch sides or play center occasionally).

One may also argue that there could have been changes in laterality over decades. Indeed, in ice hockey in general, there has been a lot of progress in training methods, including on-ice testing22. There has been changes in anthropometric and physiological variables in high level hockey over decades23. In the NHL, players are taller and have better aerobic and anaerobic capacities than they had a few decades ago24. However, we looked at the distribution of the lateral preferences of NHL players over the past 35 years and observed that the proportion of players shooting left versus right remained about the same in the different groups of our study (See S1 online).

Finally, the number of players shooting right but playing left wing provided only a small sample, especially for American players. Extending this investigation to other elite ice hockey leagues would be a welcome addition to the literature on laterality in sports. And by the same occasion, extending the analyses of the impact of laterality on ice hockey performances to women players would be most relevant considering that there is a sex difference when the link between the preferred hand in a unilateral task and the position of hands on the ice-hockey stick is analysed11.

Conclusion

This study showed that the lateral preference of NHL ice hockey players differs according to their origin. This simple fact highlights the cultural influence in lateral preferences during activities where the two hands have different roles. Both forward and defense players from the USA are more likely to shoot right than players from other countries. This lateral preference has an impact on performances, an impact interpreted as reflecting a playing style favoring either a game based on finesse, or a game focused on force. Finally, wingers shooting left have more success when playing on the right wing than when playing on the left wing, a finding that should be kept in mind by ice hockey coaches responsible for the development of young ice hockey players.

Data availability

Dataset analysed during the study are available on the NHL website (https://www.NHL.com/stats/skaters).

References

Hardyck, C. & Petrinovich, L. F. Left-handedness. Psychol. Bull. 84(3), 385–404 (1977).

Papadatou-Pastou, M. et al. Human handedness: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146(6), 481–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000229 (2020).

Raymond, M., Pontier, D., Dufour, A. B. & Møller, A. P. Frequency-dependent maintenance of left handedness in humans. Proc. Biol. Sci. 263(1377), 1627–1633. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1996.0238 (1996).

Papadatou-Pastou, M., Martin, M., Munafò, M. R. & Jones, G. V. Sex differences in left-handedness: A meta-analysis of 144 studies. Psychol. Bull. 134(5), 677–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012814 (2008).

Grondin, S., Fortin-Guichard, D., Dubeau, C.-A. & Tétreault, E. Linking the preference in a bilateral asymmetric task with handedness, footedness, and eyedness: The case of ice-hockey. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294125 (2024).

McManus, I. C., Porac, C., Bryden, M. P. & Boucher, R. Eye-dominance, writing hand, and throwing hand. Laterality 4(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/713754334 (1999).

Packheiser, J. et al. A large-scale estimate on the relationship between language and motor lateralization. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70057-3 (2020).

Grondin, S., Guiard, Y., Ivry, R. B. & Koren, S. Manual laterality and hitting performance in major league baseball. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 25(3), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.25.3.747 (1999).

McLean, J. M. & Ciurczak, F. M. Bimanual dexterity in major league baseball players: A statistical study. N. Engl. J. Med. 307(20), 1278–1279. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198211113072025 (1982).

Cairney, J., Chirico, D., Li, Y. C., Bremer, E. & Graham, J. D. Are Canadian-born Major League Baseball players more likely to bat left-handed? A partial test of the hockey-influence on batting hypothesis. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195252 (2018).

Loffing, F., Sölter, F. & Hagemann, N. Left preference for sport tasks does not necessarily indicate left-handedness: Sport-specific lateral preferences, relationship with handedness and implications for laterality research in behavioural sciences. PloS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105800 (2014).

Díaz-Pereira, M. P., López-Araujo, Y. & Lorenzo-Martínez, M. Examining variations between everyday life handedness and lateral preferences for sport-specific skills in children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 94(2), 368–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2021.1994121 (2023).

Brown, D. M., Poucher, Z. A., Myers, M., Graham, J. D. & Cairney, J. Sinister right-handedness provides Canadian-born Major League Baseball players with an offensive advantage: A further test of the hockey influence on batting hypothesis. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221501 (2019).

Voyer, D. & Wright, E. F. Predictors of performance in the National Hockey League. J. Sport Behav. 21(4), 456–473 (1998).

Puterman, J., Schorer, J. & Baker, J. Laterality differences in elite ice hockey: An investigation of shooting and catching orientations. J. Sports Sci. 28(14), 1581–1593. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.514281 (2010).

Statistica. Number of Baseball Participants in the United States from 2010 to 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/191626/participants-in-baseball-in-the-us-since-2006/ (Statistica, Accessed 10 Oct 2023).

Baseball Almanac. MLB Players by Birthplace. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/birthplace.php (Baseball Almanac, Accessed 10 Oct 2023).

National Hockey League. Skater Stats. https://www.NHL.com/stats/skaters (National Hockey League, Accessed 23 Oct 2023).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org/ (2021).

Gilbert, A. N. & Wysocki, C. J. Hand preference and age in the United States. Neuropsychologia 30(7), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(92)90065-t (1992).

Grondin, S., Trottier, M. & Houle, C. Préférences manuelle et latérale et style de jeu au hockey sur glace [Handedness and laterality and style of play in ice hockey]. STAPS 35, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.3406/staps.1994.995 (1994).

Bournival, M., Martini, G., Trudeau, F. & Lemoyne, J. The science and art of testing in ice hockey: A systematic review of 20 years of research. Front. Sports Act. Liv. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1252093 (2023).

Quinney, H. A. et al. A 26 year physiological description of a National Hockey League team. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 33(4), 753–760. https://doi.org/10.1139/H08-051 (2008).

Triplett, A. N. et al. Changes in collegiate ice hockey player anthropometrics and aerobic fitness over 3 decades. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 43(9), 950–955. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2017-0789 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council to SG. We would like to thank Charles-Anthony Dubeau for his help in the updating of the data set.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–Original Draft, Project Administration, and Funding Acquisition; P.-A.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–Reviewing and Editing. D.F.-G.: Formal Analysis and Reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grondin, S., Rioux, PA. & Fortin-Guichard, D. Analyses of the impact of laterality on performances in the National Hockey League based on players’ position and origin. Sci Rep 14, 19390 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70480-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70480-w