Abstract

Elevated serum corin concentrations in patients with cardiac diseases have been associated with adverse cardiovascular events and progressive renal dysfunction. This study aimed to determine the role of serum corin levels in predicting the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) and mortality in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs). We screened 323 patients admitted to the ICU in our institution from May 2018 through December 2019. After excluding patients receiving renal replacement therapy, 288 subjects were enrolled. Cases were divided equally into high (n = 144) and low (n = 144) corin groups according to median serum corin levels, using 910 pg/mL as the cut-off point. Patient characteristics and comorbidities were collected from medical records. The primary outcome was AKI within 48 h after ICU admission, while the secondary outcome was all-cause of mortality within 1 year. Compared with the low corin group, patients in the high corin group had higher prevalence rates of diabetes, cirrhosis, and nephrotoxic agent exposure; higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores, white blood cell counts, proteinuria, and serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels; but had lower initial estimated glomerular filtration rates. Furthermore, elevated serum corin was associated with higher risks of AKI within 48h of ICU admission (43.1% vs. 18.1%, p < 0.001) and all-cause mortality within one year (63.9% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.024). High corin level showed strongly positive results as an independent predictor of AKI (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.11–4.19, p = 0.024) but not for the all-cause mortality after adjusting for confounding factors in multivariate analyses. Elevated circulating corin predicted AKI in critically ill patients, but did not predict all-cause mortality within 1 year. As a key enzyme in renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, corin expression may be regulated through a feedback loop following natriuretic peptide resistance and desensitization of natriuretic peptide receptors in different critically ill status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corin is a type II transmembrane serine protease expressed primarily in atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes, and cleaves pro-atrial natriuretic peptide (pro-ANP) and pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP) to yield mature atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), respectively. Corin is a key enzyme in the natriuretic peptide (NP) system1,2. ANP regulates blood pressure by maintaining fluid homeostasis3 and suppresses cardiac fibroblast growth in cardiac hypertrophy4. ANP protects renal function by increasing glomerular filtration and medullary vasa recta blood flow, and by inhibiting inflammation5,6,7. Numerous corin isoforms may be detected in serum due to ectodomain shedding. Higher circulatory corin levels have been associated with improved outcomes in patients with cardiovascular diseases such as chronic heart failure (HF), acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and acute stroke8,9,10,11. Serum corin is a well-known biomarker of cardiovascular diseases and cardiac corin activity12,13, but its role in critically-ill patients is still not fully elaborated.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is among the most common organ failures in critically ill patients14,15. AKI is associated with increased mortality even without the need for dialysis15. The need for renal replacement therapy reduces in-hospital as well as long term survival16. Our previous study associated low serum corin with a higher risk of progressive renal dysfunction in patients undergoing coronary angiography17. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between circulating corin concentration and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. We hypothesized that serum corin could be a predictor of the risk of AKI and mortality in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs).

Materials and methods

Study population

A total of 323 cases admitted to ICUs in a tertiary medical center in Taiwan from May 2018 through December 2019 were screened. Thirty-five patients with end-stage renal disease and under renal replacement therapy before ICU admission were excluded. Electronic medical records of enrolled subjects were reviewed in detail to obtain patient characteristics including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HF, cirrhosis, and malignancies); premorbid medications (including ACEi, ARB, and diuretics used continuously for more than 1 month before ICU admission), and exposure to nephrotoxic agents, defined as using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aminoglycosides, and platinum-based chemotherapy within 7 days before ICU admission. Contrast exposure was recorded for the administration of nonionic low-osmolality contrast medium (iopromide) during computed tomography or angiography within 48 h before ICU admission.

The indication for ICU admission, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, laboratory data [white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin (Hgb), serum creatinine (Cr), alanine transaminase (ALT), and glucose level] at ICU transfer, and HbA1c % within 3 months before ICU admission were obtained. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight of each patient in kilograms by the square of the height in meters. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (mL/min/1.73 m2) was calculated using age, sex, and serum levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and albumin, according to the modified GFR estimating equations for Chinese patients18. Sepsis was defined according to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, e.g., as organ dysfunction reflected by a ≥ 2-point increase in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score consequent to infection19. Massive bleeding was defined as either the loss of one blood volume within 24 h, a 50% blood volume loss within 3 h, or a rate of loss of 150 mL/min20. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and our study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory values, including corin level, were obtained from each patient within 24 h after ICU admission. Serum creatinine concentration was measured at the time of ICU admission and every day during the ICU stay. Urine dipstick analysis was performed by commercial test strip, and proteinuria was defined as a urine protein ≥ 30 mg/dL. Serum concentrations of corin were determined by the commercial enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN); sensitivity was 7 ng/L. Intra‐ and interassay coefficients of variability were 4.1% and 3.9%, respectively. Enrolled patients were categorized in to two equally sized groups according to serum corin levels, as shown in Fig. 1. Subjects with serum corin levels < 910 pg/mL were assigned to the low corin group (n = 144), while those with levels ≥ 910 pg/mL were placed in the high corin group (n = 144).

End-points for clinical follow-up

The primary outcome was the incidence of AKI confirmed via The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline21 within 48 h after ICU admission. The KDIGO guideline defines AKI as either (1) an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mh/dL within 48 h; (2) a ≥ 1.5-fold increase in serum creatinine over baseline, known or presumed to have occurred within the prior seven days; or (3) urine volume < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h. All patients were followed for at least 1 year or until death. The secondary outcome was all-cause mortality within 1 year of enrollment.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normality distribution. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, or as medians and interquartile ranges according to the distribution of data. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t tests or the Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages, and analyzed using the Fisher’s exact tests or Chi-Squared tests. Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to assess correlations between corin concentrations and other clinical factors. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were used to estimate 1-year mortality. Logistic regression was performed to investigate the risk factors of AKI within 48 h after ICU admission. Cox regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of factors associated with 1-year mortality. Confounding factors associated with AKI22 and mortality23 in critically-ill patients were recorded and further adjusted in the multivariate regression analysis. To reduce overfitting and optimize model performance, variables with p values < 0.1 in the univariate regression analysis were included into a forward stepwise multivariate regression model. We selected an including threshold slightly higher than the conventional level aimed at mitigating omitted-variable bias. Sensitivity analyses using different cut-off values of corin concentrations were also performed. Serum corin concentrations was either divided by the criterion value of ROC curve (> 886.3 pg/mL, ROC curve showed in Supplementary Fig. 1), or by the corin value reported in relatively robust population undergoing coronary angiography (> 1049.9 pg/mL) in the sensitivity analyses17. To investigate the effect of corin modified by different conditions, we performed subgroup analyses with the cohort stratified by the presence of diabetes, proteinuria, initial eGFR, HF, pneumonia, sepsis, and septic shock. Factors selected into the final multivariate regression model were also adjusted in the subgroup analysis. p values < 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital, and our study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the study population was 67.5 years, and 197 (68.4%) of subjects were male. There were no differences between patients in low and high corin groups in age; gender; BMI; underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes, and HF, active malignant tumor); drug exposures (ACEi/ARB, diuretics, contrast); APACHE II scores; mechanical ventilation; inotropic agent administration; or Hgb, glucose, and lactate levels. In addition, the indications for ICU admission; including pneumonia, sepsis, acute HF, or massive bleeding; were similar between the two groups. Patients with high corin levels tended to have higher prevalence rates of cirrhosis and nephrotoxic agent exposure; and higher SOFA scores, WBC counts, proteinuria, and serum NT-pro-BNP concentrations; and were more likely to have low eGFR (Table 1).

The correlation coefficients of clinical variables to serum corin concentrations are shown in Table 2. Serum corin was positively correlated to SOFA score (r = 0.205, p = 0.001), WBC count (r = 0.133, p = 0.025), and NT-pro-BNP (r = 0.178, p = 0.002), and negatively correlated to eGFR (r = -0.335, p < 0.001). Corin level was not correlated to age (r = -0.071, p = 0.230); BMI (r = 0.059, p = 0.342); APACHE II score (r = 0.072, p = 0.224); mean arterial pressure (r = 0.005, p = 0.935); Hgb (r = -0.075, p = 0.207), glucose (r = 0.018, p = 0.780, or lactate (r = 0.059, p = 0.324) levels.

AKI and 1-year mortality after ICU admission

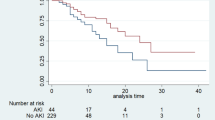

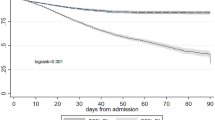

Compared to subjects with low corin levels, those with high corin levels had a higher risk of consequent AKI (18.1% vs. 43.1%, p < 0.001) that included an increased risk of stage 2–3 AKI (10.4% vs. 32.6%, p < 0.001) within 48 h of ICU admission. However, there was no difference in dialysis dependence after hospital discharge (2.1% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.138). Although the lengths of ICU stay and total hospitalization, ICU mortality, and in-hospital mortality were similar between the two groups, patients with high corin levels experienced a higher 1-year mortality rate (63.9% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.024) (Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier 1-year survival curve is shown in Fig. 2. Subjects in the high corin group had a significantly lower survival rate (log rank p = 0.0331). Furthermore, the onset of AKI within 48 h was associated with a significantly lower 1-year survival rate (log rank p = 0.0065).

Independent predictors of AKI within 48 h and 1-year mortality after ICU admission

Univariate analysis disclosed that the onset of AKI within 48 h of ICU admission was significantly associated with history of HF (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.03–4.34, p = 0.041), exposure to nephrotoxic agents (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.07–6.95, p = 0.037), higher SOFA score (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.13–1.34, p < 0.001), initial eGFR (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98–0.99, p < 0.001), proteinuria (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.25–4.53, p = 0.009), glucose (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99–1.00, p = 0.025), NT-pro-BNP (OR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.00, p = 0.045), and high corin level (OR 3.43, 95% CI 2.00–5.88, p < 0.001) at ICU admission. Multivariate regression revealed that hypertension (adjusted OR, aOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.03–3.99, p = 0.040), exposure to nephrotoxic agents (aOR 4.49, 95% CI 1.24–16.19, p = 0.022), SOFA score (aOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06–1.31, p = 0.003), initial eGFR (aOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.00, p = 0.007), glucose (aOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99–1.00, p = 0.006), and high corin level (aOR 2.15, 95% CI 1.11–4.19, p = 0.024) were still significantly associated with AKI within 48 h of ICU admission (Table 4). Sensitivity analyses using different cut-off values of serum corin concentration also showed similar findings. Even if we grouped patients according to the criterion value of ROC curve (Supplementary Table 1), or grouped by the corin value reported in relatively robust population (Supplementary Table 2), critically ill patients with higher corin levels were still significantly associated with greater risk of AKI.

Subgroup analysis disclosed that elevated corin levels were associated with a significantly increased risk of AKI in patients with sepsis (aOR 2.17, 95% CI 1.10–4.27, p = 0.025), or the absence of either HF (aOR 2.07, 95% CI 1.00–4.25, p = 0.049) or pneumonia (aOR 5.49, 95% CI 1.10–27.43, p = 0.038) after adjusting for confounding factors. Nevertheless, there was no statistical difference in interaction tests (Table 5).

Univariate analysis revealed that underlying hypertension (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.44–0.83, p = 0.002), active malignancy (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.25–2.28, p = 0.001), APACHE II score (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05–1.09, p < 0.001), SOFA score (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.11–1.22, p < 0.001), administration of inotropic agents or vasopressors (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.24–2.34, p = 0.001), mean arterial pressure (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.99, p < 0.001), Hgb (OR 0.86, 95% CI 1.80–0.93, p < 0.001), lactate (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.02, p < 0.001), confirmed AKI in ICU (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.13–2.13, p = 0.007), and elevated corin (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1..02–1.90, p = 0.035) were significantly associated with 1-year mortality. Multivariate analysis disclosed that hypertension (aOR 0.61, 95% CI 0.42–0.89, p = 0.009), active malignancy (aOR 1.52, 95% CI 1.07–2.16, p = 0.019), APACHE II score (aOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, p = 0.015), SOFA score (aOR 1.10, 95% CI 1.08–1.17, p = 0.005), and lactate level (aOR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02, p = 0.042) were independently associated with 1-year mortality. High corin level was not an independent predictor for 1-year mortality in the multivariate analysis (Table 6).

Discussion

As a key enzyme in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), corin prevents the development of dilated cardiomyopathy by down-regulating RAAS activation, and its circulating level may serve as a valuable prognostic indicator of cardiac function. Serum corin concentrations was reported to have good prognostic value in patients with coronary artery disease17 and HF24. This is the first study to measured corin in critically ill patients. This study illustrated that an elevated corin level on ICU admission is a useful biomarker to predict the onset of AKI within 48 h and may indicate an increased risk of 1-year mortality.

Corin and heart failure

Serum corin is a well-documented biomarker associated with the regulation of blood pressure and cardiac function3,25. Intraperitoneal administration of soluble corin in murine models of HF enhanced NP processing and activity, suppressed RAAS, and improved cardiac function and morphology26. Impaired corin expression and function were related to HF26. Patients with HF exhibited low serum corin levels9,27. Coincidentally, a case–control study disclosed that patients with HF were more likely to have elevated serum NT-pro-BNP and low corin levels. Furthermore, decreased corin levels were associated with higher severity of HF25,28, and the progressive decline of corin levels has been used as a sensitive indicator of early systolic dysfunction before incipient HF28. A previous study associated a high circulating corin level (> 721 pg/mL) with fewer major adverse cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction; however, patients in the low corin group tended to have underlying of HF and hypertension which led to low corin levels9. In our analysis, the prevalence of hypertension and HF were similar between the high and low corin groups (Table 1). Moreover, no interaction was found in subgroup analysis (Table 5).

Corin and renal function

Serum corin mitigates progressive renal dysfunction by increasing glomerular filtration and medullary vasa recta blood flow, and by inhibiting inflammation17. Our previous studies indicated that a low serum corin level (cutoff level < 1049.9 pg/mL) is a strong independent risk factor for progressive renal dysfunction but not for contrast-induced nephropathy developing within 48 h of coronary angiography17. In this study, high corin levels in patients with acute critical illness exhibited a highly negative correlation to initial eGFR and was associated with AKI within 48 h. On the other hand, similar to the expression of corin in chronic HF, low renal corin levels promoted sodium retention in rat models of nephrotic syndrome and glomerulonephritis29. Due to the different clinical contexts and corin levels mentioned above, corin may enhance the conversion of pro-ANP to ANP during acute illness in response to oxidative stress and renal inflammation, but not in late-phase or chronic disease30,31. ANP resistance may be caused by desensitization of natriuretic peptide receptor-A after chronic ANP stimulation32. We propose that elevated circulating corin levels indicate NP resistance and natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR) desensitization. High serum corin level could be recognized as an antecedent indicator of ANP synthesis only during acute illness. Therefore, treatment with human ANP has no benefit in reducing neither the requirement for dialysis nor death in critically ill patients who developed AKI during ICU stays33. Patients with effective NP utilization during acute illness reveal lower serum NT-pro-BNP levels and thus exhibit with lower corin levels (low corin group). Conversely, high serum corin and NT-pro-BNP were found in patients with ineffective NP utilization (high corin group). This positive correlation between corin and NT-pro-BNP levels would be compatible with the results shown in Table 2. Nevertheless, once NP resistance is established in chronic illness, high ANP/BNP levels might act through a negative feedback loop to inhibit corin synthesis, leading to a low circulating level. Consequently, the reversal of corin levels from high to low may thus be compatible with the transformation from acute to chronic disease (Fig. 3), as a reduced corin level has been recognized as a predictor for early cardiac dysfunction and development of HF28.

Corin as biomarker of disease severity and mortality

Cardiac dysfunction is a common and potentially lethal complication of sepsis. Therefore, predictors of heart function after acute illness become significant prognostic factors of outcomes of patients under intensive care. Although the mechanism of pro-ANP release during sepsis needs further study, pro-ANP on the day of admission has been proven as a valuable prognostic marker for risk assessment that is similar to the APACHE II score and performs better than C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels34,35. The pro-ANP value is significantly lower in sepsis survivors than nonsurvivors34. The proteolytic cleavage of pro-ANP by corin to yield ANP may play a pivotal role and may indicate NPR desensitization (Fig. 3).

On the other hand, elevated NT-pro-BNP and BNP levels caused by volume retention, HF, and poor renal clearance were meaningful predictors of mortality in chronic renal disease despite the lack of an established connection between the two predictors and increased mortality30. Elevated NT-pro-BNP (value ≥ 3270 pg/mL) is a well-known biomarker of left ventricular dysfunction36; furthermore, tachycardia occurring with concurrently increased NT-pro-BNP tended to predict poor outcomes in septic ICU patients37. To summarize, increased NT-pro-BNP, as a cleavage product of pro-BNP generated through the proteolytic activity of corin, could indicate deteriorating cardiac function in sepsis patients. We observed that patients in the high corin group also had higher NT-pro-BNP levels (5319 vs. 4185 pg/mL; p = 0.012) (Table 1). An investigation of the potential utility of the combination of neprilysin, a zinc-dependent metalloprotease that degrades active NPs, and corin to stratify patients with chronic HF revealed that the group with both neprilysin and corin elevations experienced higher mortality due to cardiovascular death and HF24. Because NT-pro-BNP and BNP have been used as diagnostic biomarkers for HF and are associated with increased in-hospital mortality38, corin may be reasonably considered as a novel indicator for predicting outcomes of acute critical illness (Fig. 3). The results of previous studies24,38 were similar to our finding that high corin levels correlated to an increased risk of AKI within 48 h of acute status and to a higher 1-year mortality via a gradual loss of NP-mediated suppression of the RAAS.

Limitations

This single-center study was limited by its relatively small case numbers. Because this study did not include healthy controls, it lacked a comparison of serum corin levels between patient and normal populations. Underlying diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, renal insufficiency, and HF may have influenced corin levels. Our adjusted analyses may have missed unidentified confounding factors. The etiologic relationship between elevated corin levels and AKI should be confirmed in further prospective or interventional studies.

Conclusions

Among critically ill patients, a high circulating corin level may be a valuable predictor of AKI within 48 h of ICU admission. Although the corin level was not an independent predictor of 1-year mortality, it was to a certain degree correlated with all-cause death within 1 year. In our opinion, increased corin levels indicate NP resistance and NPR desensitization. This study provides indirect evidence of corin's involvement in the pathophysiology of AKI.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- ICUs:

-

Intensive care units

- pro-ANP:

-

Pro-atrial natriuretic peptide

- pro-BNP:

-

Pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- ANP:

-

Atrial natriuretic peptide

- BNP:

-

Brain natriuretic peptide

- NP:

-

Natriuretic peptide

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- Hgb:

-

Hemoglobin

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- KDIGO:

-

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- RAAS:

-

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- NPR:

-

Natriuretic peptide receptor

References

Hooper, J. D., Scarman, A. L., Clarke, B. E., Normyle, J. F. & Antalis, T. M. Localization of the mosaic transmembrane serine protease corin to heart myocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 267(23), 6931–6937 (2000).

Wu, Q. The serine protease corin in cardiovascular biology and disease. Front. Biosci. 12, 4179–4190 (2007).

Li, H., Zhang, Y. & Wu, Q. Role of corin in the regulation of blood pressure. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 26(2), 67–73 (2017).

Ellmers, L. J. et al. Ventricular expression of natriuretic peptides in Npr1(-/-) mice with cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283(2), H707–H714 (2002).

Marin-Grez, M., Fleming, J. T. & Steinhausen, M. Atrial natriuretic peptide causes pre-glomerular vasodilatation and post-glomerular vasoconstriction in rat kidney. Nature 324(6096), 473–476 (1986).

Kiberd, B. A., Larson, T. S., Robertson, C. R. & Jamison, R. L. Effect of atrial natriuretic peptide on vasa recta blood flow in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 252(6 Pt 2), F1112–F1117 (1987).

Mitaka, C. et al. Effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on inter-organ crosstalk among the kidney, lung, and heart in a rat model of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Intens. Care Med. Exp. 2(1), 28 (2014).

Zhou, X. et al. Plasma corin as a predictor of cardiovascular events in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 4(8), 664–669 (2016).

Zhou, X. et al. Prognostic value of plasma soluble corin in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67(17), 2008–2014 (2016).

Hu, W. et al. Serum soluble corin deficiency predicts major disability within 3 months after acute stroke. PLoS ONE 11(9), e0163731 (2016).

Peleg, A., Ghanim, D., Vered, S. & Hasin, Y. Serum corin is reduced and predicts adverse outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2(2), 159–165 (2013).

Dong, N., Chen, S., Wang, W., Zhou, Y. & Wu, Q. Corin in clinical laboratory diagnostics. Clin. Chim. Acta 413(3–4), 378–383 (2012).

Zhou, Y. & Wu, Q. Corin in natriuretic peptide processing and hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 16(2), 415 (2014).

Gammelager, H. et al. One-year mortality among Danish intensive care patients with acute kidney injury: A cohort study. Crit. Care 16, R124 (2012).

Clermont, G. et al. Renal failure in the ICU: Comparison of the impact of acute renal failure and end-stage renal disease on ICU outcomes. Kidney Int. 62, 986–996 (2002).

Schiffl, H., Lang, S. M. & Fischer, R. Long-term outcomes of survivors of ICU acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy: A 10-year prospective cohort study. Clin. Kidney J. 5, 297–302 (2012).

Yang, S. F., Chou, R. H., Li, S. Y., Huang, S. S. & Huang, P. H. Serum corin level is associated with subsequent decline in renal function in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7(10), e008157 (2018).

Ma, Y. C. et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17(10), 2937–2944 (2006).

Rhodes, A. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intens. Care Med. 43(3), 304–377 (2017).

Stainsby, D., MacLennan, S. & Hamilton, P. J. Management of massive blood loss: A template guideline. Br. J. Anaesth. 85(3), 487–491 (2000).

Khwaja, A. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 120(4), c179–c184 (2012).

Thongprayoon, C. et al. Diagnostics, risk factors, treatment and outcomes of acute kidney injury in a new paradigm. J. Clin. Med. 9(4), 1104 (2020).

Vallet, H. et al. Mortality of older patients admitted to an ICU: A systematic review. Crit. Care Med. 49(2), 324–334 (2021).

Gommans, D. H. F. et al. Soluble neprilysin and corin concentrations in relation to clinical outcome in chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 9(2), 85–95 (2021).

Yu, Z. et al. Serum corin is associated with the risk of chronic heart failure. Oncotarget 8(59), 100353–100357 (2017).

Niu, Y. et al. Recombinant soluble corin improves cardiac function in mouse models of heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10(7), e019961 (2021).

Dong, N. et al. Plasma soluble corin in patients with heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 3(2), 207–211 (2010).

Tripathi, R. et al. Depressed corin levels indicate early systolic dysfunction before increases of atrial natriuretic peptide/B-type natriuretic peptide and heart failure development. Hypertension 67(2), 362–367 (2016).

Polzin, D. et al. Decreased renal corin expression contributes to sodium retention in proteinuric kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 78(7), 650–659 (2010).

Shah, A., Gao, S., Oh, Y. B., Park, W. H. & Kim, S. H. Oxidative stress augments the secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide in isolated rat atria. Peptides 32(6), 1172–1178 (2011).

Della Penna, S. L., Rosón, M. I., Toblli, J. E. & Fernández, B. E. Role of angiotensin II and oxidative stress in renal inflammation by hypernatremia: Benefits of atrial natriuretic peptide, losartan, and tempol. Free Radic. Res. 49(4), 383–396 (2015).

Fujii, T. et al. Human atrial natriuretic peptide for acute kidney injury in adult critically ill patients: A multicenter prospective observational study. J. Crit. Care 51, 229–235 (2019).

Theilig, F. & Wu, Q. ANP-induced signaling cascade and its implications in renal pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 308(10), F1047–F1055 (2015).

Morgenthaler, N. G., Struck, J., Christ-Crain, M., Bergmann, A. & Müller, B. Pro-atrial natriuretic peptide is a prognostic marker in sepsis, similar to the APACHE II score: An observational study. Crit. Care 9, R37–R45 (2005).

Lipinska-Gediga, M., Mierzchala, M. & Durek, G. Pro-atrial natriuretic peptide (pro-ANP) level in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: Prognostic and diagnostic significance. Infection 40, 303–309 (2012).

Yu, J., Zheng, R., Yang, P. & Wang, D. Construction of a predictive model and prognosis of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with sepsis based on the diagnosis using left ventricular global longitudinal strain. J. Intens. Care 10(1), 29 (2022).

Hayase, N. et al. Association of heart rate with N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in septic patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Shock 46(6), 642–648 (2016).

Benmachiche, M., Marques-Vidal, P., Waeber, G. & Méan, M. In-hospital mortality is associated with high NT-proBNP level. PLoS ONE 13(11), e0207118 (2018).

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 104-2314-B-075-047, MOST 106-2314-B-010-033-MY3, MOST 106-2314-B-075-078-MY3), the Novel Bioengineering and Technological Approaches to Solve Two Major Health Problems in Taiwan sponsored by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology Academic Excellence Program (MOST 108-2633-B-009-001), the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW106-TDU-B-211-113001), Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V105C-207, V106C-045, V108C-195, V110C-165, V111-190), and the Integrated Research Program of Cheng Hsin Hospital and National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (CY113-11206-04, CY113-11206-05). These funding agencies had no influence on the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PHH & RHC conceived of the presented idea. JYG & RHC analyzed and interpreted the patient data. CEC & JYG drafted and wrote the manuscript. CEC, JYG, RHC, CHW, CSK, JHW & PHH contributed to the interpretation of the results. Both PHH & RHC contributed to the final version of the manuscript. PHH supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, CE., Guo, JY., Chou, RH. et al. Circulating corin concentration is associated with risk of mortality and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Sci Rep 14, 19848 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70587-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70587-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Beyond Natriuretic Peptides: Corin and Furin As Phenotype-Specific Biomarkers and Therapeutic Gatekeepers in Heart Failure

Current Heart Failure Reports (2025)