Abstract

In this paper, a dynamic quadrotor unmanned aircraft vehicle driven by bidirectional electronic speed controllers is proposed to enhance maneuverability and stability. Bidirectional electronic speed controllers are applied to achieve rapid deceleration of motors during flight. To match with bidirectional electronic speed controllers, fractional order Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers are considered to attain better rapidity compared to PID controllers, and an innovative control allocation matrix with direction symbols is developed. The model, controllers, and allocation methods have been proven an effective scheme in simulations of attitude and position tracking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The features and defects

The multi-rotor-aircrafts including quadrotor unmanned aircraft vehicles (QUAV) are widely studied due to the potential value in search and rescue operations, first aid response, traffic control missions, infrastructure support, aerial photography, film shooting and other aspects. Its advantages include the simplicity in mathematical modeling, mechanical structure, control algorithm and modularity, which enable the diversified modification. However, there exists defects in a QUAV, which can be mainly reflected in the following aspects:

-

1.

Underactuation: A QUAV achieves attitude and position control by balancing the thrust and torque generated by four blades. The limited inputs implies that a QUAV is a typical underactuated system1,2,3, that is, the number of inputs (four labeled motors and the thrust arrows in Fig. 1) is less than 6-DOF (six degrees of freedom: roll: ϕ, pitch: θ, yaw: ψ, and x–y-z position in Fig. 1). This drawback greatly affects the maneuverability and robustness of a QUAV.

-

2.

Coupling: Due to the limit of body structure, a QUAV usually owns fixed motors to provide lift at an upward direction, which means the changing attitude is a prerequisite for changing position, and the control of position and attitude is coupled4,5.

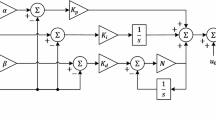

As a result, the attitude and position controllers are usually cascade6, that is, the attitude controller forms the inner loop and the position controller forms the outer loop, as Fig. 2. It is necessary to compensate for the quality of control in other ways.

-

3.

Nonlinearity: There is no simple linear mappings between the above-mentioned inputs and outputs, that is, the complete 6-DOF dynamic model of the quadrotor is a highly nonlinear one7. For this reason, to eliminate nonlinearities, along with the disturbances caused by model uncertainty, some optimal control methods applied in other nonlinear objects such as robotic manipulators8 and gas compressor9 can be referred to.

The three aspects obviously magnifies the instability in the case of intense maneuver. Besides, considering the outdoor operation scenarios10,11, the mobility defects dramatically affect a QUAV as a work platform. Thus, the enhancement of maneuverability and stability has been an important work in research and engineering. There are three main aspects as the crucial components of a QUAV to be discussed: controller, control allocation and actuator.

Controller, control allocation and actuator

-

1.

Controller: The control issue of QUAV is essentially the optimization of multi-motors, and similar control problems have been discussed in objects driven by multiple motors, such as electric vehicles, hexacopters and octacopters12,13,14,15. However, the QUAV has more degrees of freedom and only four control inputs, which will cause the multi-motors control problem to be reconsidered. Due to the coupling relationship of underactuated QUAVs, real-time position and attitude data enters into position and attitude controllers respectively, while the output of position controller is the desired input of attitude controller. A typical representative of the above structure is PID controller. As a controller with simplicity and improvement potential, the existing results16,17,18,19 reveal the following tasks that PID-QUAVs can achieve: automatic landing/take off, attitude/trajectory tracking, obstacle avoidance and so on. However, the control quality of PID is seriously degraded when the controlled object is strongly coupled, nonlinear and with excellent dynamic characteristics and small time constant, such as the first person view QUAV20, or ordinary QUAVs with high mobility requirements21. Thus, the improved or hybrid PID controllers are applied, some representative results are: A novel fuzzy PID iterative learning controller (ILC) is designed for a QUAV22. PID-ILC control and fuzzy control are combined, so the robustness of ILC to disturbances and uncertainties is inherited. This method is partially limited to the repetitive motion systems.

In23, an adaptive PID scheme based on second-order sliding mode control and fuzzy compensation system to control a QUAV is introduced. The self-tuning characteristics of the controller are based on Lyapunov stability theory and gradient descent method.

The literature24 proposes an active disturbance rejection PID controller to resist disturbance and realize trajectory tracking, but stability analysis nor experiments were provided. The work25 develops a cascade intelligent controller composed of fuzzy neural network and a fuzzy neural network-based PID scheme for a QUAV. The fuzzy neural network and the PID scheme are trained offline and online respectively to deal with attitude and position dynamics. The present article adopts a fractional PID controller to compensate for the external disturbance and the error caused by model parameter, with improvements on traditional PID controllers.

-

2.

Control allocation: The control allocation refers to the mapping from control command of thrust and torque to rotor speed. When large alterations are made to actuators, allocation method is vitally important since only if it is designed reasonably, mobility and stability can be achieved. Literature26 shows that the aerodynamic effects of QUAVs can be compensated by means of a neural-networks-based allocation approach, without using the aerodynamic inflow equations directly. The network training is performed offline, which requires minimal computational resources. In27, variable-pitch propellers are applied, thus an actuator allocation method is developed with the aim of enhancing the attitude control and energy performance. Literature21 adopts additional dynamics of the control allocation loop to ensure stability of the full system, which includes the outer or position control loop, the intermediate or attitude control loop, and the innermost or the control allocation loop. Similar tilt-rotor QUAV also appears in28, where a fast control allocation matrix with non-unique solutions is developed. Torque, dynamics and velocity are represented in the matrix to achieve convergence and robustness. This present article demonstrates an improved allocation method to collaborate with the fractional PID controller and fixed actuators, which means the structure of allocation matrix almost remains the previous scheme. However, in order to achieve the bidirectional rotation of the motor driven by bidirectional current, the allocation matrix must be redesigned to fit the electronic speed controllers (ESCs).

-

3.

Actuator: The actuators, especially power components of a QUAV mainly include ESCs, motors and blades, as the 1, 2, 3 in Fig. 3 below respectively:

During the flight, once attitude and position errors are detected by sensors (gyroscope, accelerometer and GPS) on board, flight controllers will generate modulated waves to ESCs, which distribute the current from batteries29. The modulated current drives motors to change rotation speed, and the attached blades generate thrust and torque to drive QUAV to eliminate errors. The current mentioned above is usually unidirectional, causing the changing rate of thrust and torque relatively small.

To overcome the above defects, some work applies variable-pitch-blades, which achieve bidirectional thrust by means of adjusting the pitch angles of blades27,30. It offers bidirectional thrust to adjust attitude and position rapidly, but the work requires complex controllers for variable pitch structures (to control pitch angles of blades in addition to speed), thus deteriorates the disadvantages of small payload and short endurance. Some work applies sloping motors, which increases control in puts and transforms a QUAV from underactuated to overactuated system28,31. It effectively resists disturbance, but the tilt angle of motors is limited (less than 90 degrees), and the input range for improving dynamic characteristics is incomplete, while it also increases weight and hardware cost. Some literature32,33 suggests that bidirectional ESCs generate bidirectional current and drive motors to rotate bidirectionally. The work enables a QUAV to hover after flip and other maneuvers. However, it does not analyze the advantages of bidirectional current in improving the dynamic characteristics of control, especially attitude tracking, nor does it discuss the control allocation matrix from bidirectional motor speed to torque and thrust. Considering the existing work, this paper adopts bidirectional ESCs and redesigned control allocation matrix, which can not only improve the maneuverability, but also avoid making major changes to the structure of QUAV. It is only necessary to replace the ESCs and reprogram the control allocation code, making use of the modularity of QUAV. Furthermore, this paper also analyzes the advantages of bidirectional-ESC-QUAV in attitude and trajectory tracking.

The arrangement of work

A QUAV with bidirectional ESCs, supported by cascade controllers and allocation matrix is developed in this work. Bidirectional ESCs can drive motors to decelerate or reverse rotation rapidly during flight. The paper is arranged as follows in Fig. 4: The dynamics modeling of a QUAV is illustrated in section “QUAV model”. The position and attitude controllers are conducted in section “Attitude and position controllers”. The control allocation matrix to realize the mapping of thrust and torque to motor speed is proposed in section “Control allocation”. The results and analysis of simulation are demonstrated in section “Simulation”. The summary and outlook are in section “Conclusion”.

QUAV model

In this section, the dynamic model of a QUAV is presented. Considering the potential singular point occurred due to multiple rotation maneuvers, quaternion is utilized to describe attitude34.

Predefinition:

Def.1 Every part of a QUAV is rigid including body structure, motors, and blades, which will not produce deformation in any maneuvering situation.

Def.2 The QUAV’s CoG (center of gravity) coincides with the origin of body axis, the mass of other parts is not considered.

Def.3 The QUAV is symmetrical along the x and y axes of body frame35.

Figure 5 depicts the body frame \(O_{b} x_{b} y_{b} z_{b}\) rotates \(\phi\) to a new frame \(O_{g} x_{g}^{\prime } y_{g}^{\prime } z_{g}^{\prime }\) around axis \(ON\).

Define the quaternion as follows (1, 2):

where \(\alpha\) is the angle of rotation, \(N_{x}\),\(N_{y}\) and \(N_{z}\) are the directional cosine of \(ON\) in \(O_{b} x_{b} y_{b} z_{b}\). The quaternion satisfies the following constraints (3):

The transformation matrix \({\mathbf{R}}_{iu}\) from body frame to inertial frame is as (4)16, \((\phi ,\theta ,\psi )\) represents attitude angles (roll, pitch, yaw):

The above formula (4) can be converted into (5) below, in the form of quaternion using (2), for the subsequent matrix transformation:

The CoG dynamics model of a QUAV32,36 is:

where (6) and (7) represent the formulas of thrust and torque respectively, and (8) indicates the orientation of QUAV. (9) is the skew symmetric matrix, representing cross multiplication. The symbols and their corresponding meanings are shown in Table 1:

Attitude and position controllers

The position and attitude control of a QUAV is often realized by cascade PID controllers, i.e. the output command of the position controller is transmitted to the attitude controller. Due to differential flatness37, the control input \({\mathbf{F}}_{T}\), \({{\varvec{\uptau}}}\) can be obtained from \({{\varvec{\upeta}}}\), but for the purpose of controlling attitude without position controller in section “Control allocation”, cascade PID controller is applied. The position controller to track desired position \({{\varvec{\upeta}}}_{d} = (x_{d} \quad y_{d} \quad z_{d} )^{T}\) is as (10) below:

where \({\mathbf{K}}_{d} \in \Re^{3 \times 3}\) is differential coefficient diagonal matrix, \({\mathbf{K}}_{p} \in \Re^{3 \times 3}\) is the proportional coefficient diagonal matrix, \({\mathbf{\ddot{\eta }}}_{d}\) is the desired acceleration, \({\tilde{\mathbf{\eta }}} = {{\varvec{\upeta}}}_{d} - {{\varvec{\upeta}}}\) is position error; For subsequent attitude controller design, the desired attitude \({\mathbf{q}}_{d}\) can be obtained from thrust \({\mathbf{F}}_{i} = {\mathbf{R}}_{iu} ({\mathbf{q}}){\mathbf{F}}_{T}\) in (10)38, as (11):

where \({\mathbf{F}}_{b} = (0\quad 0\quad \pm 1)^{T}\) makes \({\mathbf{F}}_{b}^{T} {\mathbf{F}}_{i} \ge 0\). Therefore, \({\mathbf{R}}_{iu} ({\mathbf{q}}_{d} )\) can be obtained using (11). In order to construct the subsequent control allocation matrix, the attitude controller is written in the following format31:

where \({\mathbf{K}}_{\omega d}\) is the differential gain matrix of angular velocity error, \({\mathbf{K}}_{\omega p}\) is the diagonal matrix of angular velocity proportional gain, \(({\mathbf{R}}_{id}^{T} ({\mathbf{q}}_{d} ){\mathbf{R}}_{iu} - {\mathbf{R}}_{iu}^{T} ({\mathbf{q}}_{d} ){\mathbf{R}}_{id} )^{ \vee } /2\) is the attitude tracking error vector obtained from diagonal matrix39, within which \({\mathbf{R}}_{id} = {\mathbf{R}}({\mathbf{q}}_{d} ){\mathbf{R}}_{z} (\psi )\) is the resulting rotation matrix, and \({\mathbf{R}}({\mathbf{q}}_{d} )\) represents Euler-Rodrigues formula. Since the yaw angle \(\psi\) can be selected freely as needed for the task, for simplicity, \({\mathbf{R}}_{id} = {\mathbf{R}}({\mathbf{q}}_{d} )\) is set for this work.

After transforming the desired acceleration of roll, pitch and yaw to desired torque, they will come into control allocation matrix in section “Control allocation” together with desired thrust. Finally, the output of matrix conducts desired rotation speed to motors. The controller structure is as depicted in Fig. 2 in the introduction part.

Furthermore, for comparison, an improved scheme is fractional order position controllers (FOPID) \(C_{FOPID} (s)\). Considering that the four rotor model with the inner velocity loop is considered as a second-order system \(P(s)\). In the frequency domain, which can be identified using System Identification Toolbox in Matlab40, as in Fig. 6.

Based on the existing PID controller, the fractional order controller is (13):

where \(\mu ,\lambda \in [0,1][0,1]\) are the fractional orders. Thus, the open loop transfer function is \(G(s) = C_{FOPID} (s)P(s)\). As for the tuning, given the expected gain crossover frequency \(\omega_{c}\) and phase margin \(\phi_{{\text{m}}}\), the performance specifications are listed below41:

where at the gain crossover frequency in (16), the phase derivative (frequency) is zero, which indicates the system is more robust to gain changes. Other parameters can be obtained by satisfying the above three equations.

Control allocation

The mapping from thrust and torque to motor speed is discussed in the section, that is, control allocation. The calculation result is represented as motor speed, then the required PWM duty cycle is obtained by motor speed-PWM mapping. The logical level of flight control is in Fig. 7:

The total torque generated by motors is as follows in (17):

where the first term is the torque of pitch and roll, whose direction is determined by \({\mathbf{r}}_{i}\); The second term is the torque of yaw perpendicular to the plane of \({\mathbf{n}}_{i}\); \(P_{i} \in \{ - 1,1\}\), 1 represents clockwise (CW) and − 1 represents counterclockwise (CC), which is determined by the motor.

Transform (17) into a matrix (18):

where the desired \({\mathbf{F}}_{T}\) and \({{\varvec{\uptau}}}\) are derived from position and attitude controllers in section “Attitude and position controllers”. To obtain desired \(\Omega_{i}\), linearization method is used through the relationship between measured \(\Omega_{i0}\) with target thrust \({\mathbf{F}}_{i}\) and torque \({{\varvec{\uptau}}}_{i}\):

The existing allocation matrix (21) represents the number and rotation direction of motors:

It is obvious that yaw and roll/pitch are independent, so the three blocks (thrust, roll/pitch and yaw) can be combined into one matrix (22):

The constant mapping from speed to thrust and torque is expressed as \(c_{f}\) and \(c_{\tau }\).

To facilitate mapping representation, define a block diagonal matrix as follows (23):

The matrix corresponding to (19) and (20) is defined:

The control allocation matrix \({\mathbf{B}} = {\mathbf{CA}}\) is similar to \(({\mathbf{F}}\quad {{\varvec{\uptau}}})^{T} = {\mathbf{B}}(\Omega_{1}^{2} \quad \cdots \quad \Omega_{N}^{2} )^{T}\), the desired motor speed can be written on the left side of equation:

where \(\Omega_{i0}\) can be obtained from ESCs; \(F_{i0}\) and \(\tau_{i0}\) can be obtained from calculation. Since the desired motor speed has been obtained, then the required PWM duty cycle is obtained by motor speed-PWM mapping.

It is notable that the motors with same parity number may have different directions when the QUAV is rolling and pitching drastically. \(O_{i} \in \{ - 1,1\}\) is defined as the direction symbol of \(NO.1\) and \(NO.3\) motors, 1 represents CC, – 1 represents CW; \(E_{i} \in \{ - 1,1\}\) is defined as the direction symbol of \(NO.2\) and \(NO.4\) motors, 1 represents CW, – 1 represents CC:

The corresponding control allocation matrix is:

(27) can be transformed into the form of (28):

Remark: The above matrix has never been applied in other QUAV works before for control allocation, and the innovation lies in the speed regulation strategy. When attitude and position deviation is detected by IMU, the control quantities, either positive or negative, which are generated by flight controllers, namely, the bipolar PWM signals, will be transformed to ESCs. Then, the three-phase currents with different phase sequences generated by ESCs drive the motors to rotate. During the acceleration phase, the motor performance is no different from other control schemes. However, during the deceleration phase, the reverse current can drive the motor to rapidly decelerate instead of merely relying on inertia and friction, meanwhile \(E_{i}\) and \(O_{i}\) will change. Combined with the previous FOPID controller, it is very helpful in reducing overshoot and adjustment time. Further, due to the presence of reverse thrust, QUAVs can perform actions that were previously impossible, such as hovering after flipping 180 degrees, or closely adhering to vertical walls (flip 90 degrees) and ceilings (flip 180 degrees). The above tasks rely on reasonable trajectory planning, controllers and actuators, providing the possibility for expanding the working scenarios of QUAVs.

Simulation

The QUAV model is built as the controlled object, including the frame and controllers mentioned above, the actual size grid, mass, moment of inertia and other actual physical quantities. Four motors integrated with bidirectional ESCs are installed as actuators. The moment of inertia of motors, coil resistance, counter EMF coefficient and other parameters are set according to the actual QUAV. The QUAV simulation system used in this paper is built in Simulink, and the model is divided into five parts: (1) Cascade attitude and position controller with angle conversion module. (2) Control allocation, ESCs and motors. (3) Mechanical structure and environment. (4) Thrust calculation and generation. (5) Calculation and feedback of physical quantity. As illustrated in Fig. 8:

Rotor current in height tracking: To verify the validity of bidirectional ESCs and control allocation matrix, the simulated QUAV is set to track four step-height changes after taking off and the current to motors is analyzed to confirm the function of bidirectional ESCs. Since the change of attitude angle is not involved, the speed of four motors is exactly the same, so is the time–current result of each motor. \(No.1\) motor is taken as an example and results are depicted in Fig. 9 below, (a) and (b) are the overall and partial (the first step) diagrams respectively:

At the four moments when the desired height changes, namely the 5 s, 10 s, 15 s and 20 s, the current changes over zero point because ESCs apply reversed current to make motors decelerate rapidly.

Roll and pitch angles tracking: QUAVs are set to track roll and pitch angles simultaneously, that is, \(x(t) = 20cos(t)^{^\circ }\), \(y(t) = 20sin(t)^{^\circ }\) and \(\psi_{des} = 0^{^\circ }\). Figure 10 below represents roll and pitch angles respectively, combining the results, it can be merged into \(x - y\) plane. The QUAV rotates at \(20^{^\circ }\) in both roll and pitch angles.

Step height tracking: QUAVs take off and reach a step height of 22.5 m, as shown in Fig. 11. Figure 11a illustrates the desired height and QUAVs’ responses, and Fig. 11b is the magnification of the step peak.

Bidirectional-ESC-QUAV achieves fast and active deceleration beyond the desired height, with less fluctuation and adjusting time.

Spiral trajectory tracking: The objective functions of trajectory are set as \(x(t) = 2sin(0.1t)\), \(y(t) = - 2cos(0.1t)\) and \(z(t) = 0.1t\), the combination will be presented as spiral curves. Two QUAVs are programmed to take off from the origin. The result is depicted in Fig. 12 and the indexes are listed in Table 2, in which RMSEx/y and the sums of 3D Euclidean distance are used to present the errors in x/y directions. The time period from the beginning to the Euclidean distance error of less than 5% is considered as the adjustment time.

Discussion: Although bidirectional ESCs have been applied in other works, like32,33, they did not discuss the performance of simultaneous tracking of multi axis attitude and position, especially with the new control allocation method. In roll and pitch angles tracking simulation (Fig. 10), at the initial stage of tracking, the deviation is large, so both QUAVs show overshoot, but since bidirectional-ESC-QUAV applies the control method of active deceleration after overshoot, the overshoot is relatively small; in the subsequent stage, after about 2.2 s, due to the small track change rate and no overshoot, the performances of the two quadrotors are similar; in the subsequent stage, that is 2.2 s, the overshoot did not appear due to the small change rate of the desired trajectories. The differences of overshoot phenomena between the two QUAVs also appears in step height tracking simulation (Fig. 11). It is evident that from the results of spiral trajectory tracking (Fig. 12), the control strategy of FOPID tends to reduce adjustment time and oscillation, especially in x/y directions, which is consistent with the advantages of bidirectional-ESC. So if the parameters are tuned reasonably, in simulation scenarios that pursue rapidity at initial stage, QUAV equipped with bidirectional ESCs and FOPID controllers performs well. The main advantages of bidirectional-ESC QUAV are: To achieve rapid motor deceleration and reduce overshoot, especially under high-speed maneuvering conditions, while in the acceleration stage, the difference is less obvious. Additionally, the update of controller and control allocation method only requires reprogramming, the method proposed in this work can be applied to some existing QUAVs pursuing high maneuverability without changing the body structure.

Conclusion

A QUAV with bidirectional ESCs is proposed in the work. Based on quaternion, the dynamic model of QUAV is established, and the supporting PID/FOPID controllers and control allocation matrix with direction symbols are designed. The performances of attitude and position tracking of QUAV with the above components are tested in simulations. FOPID and control allocation methods have been proven effective in reducing deviation and increase control speed. In the future, controllers and allocation matrix will be further upgraded, and the effect of bidirectional-ESC on severe maneuvers such as flip will be considered. Improvements will be verified in simulations and experiments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abro, G., Zulkifli, S., Ali, Z., Asirvadam, V. & Chowdhry, B. Fuzzy based backstepping control design for stabilizing an underactuated quadrotor craft under unmodelled dynamic factors. Electronics 11, 999 (2022).

Lin, J. et al. Error-state LQR geofencing tracking control for underactuated quadrotor systems. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 29, 1146–1157 (2024).

Xu, Y., Qu, Y., Luo, D. & Duan, H. Distributed fixed-time time-varying formation-containment control for networked underactuated quadrotor uavs with unknown disturbances. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 130, 107909 (2022).

Zhou, Z., Wang, H. B., Wang, Y. L., Xue, X. J. & Zhang, M. Q. Distributed formation control for multiple quadrotor UAVs under Markovian switching topologies with partially unknown transition rates. J. Franklin Inst. 356, 5706–5728 (2019).

Mystkowski, A. Implementation and investigation of a robust control algorithm for an unmanned micro-aerial vehicle. Robot. Autonom. Syst. 62, 1187–1196 (2014).

Qiao, Z., Zhu, G. X. & Zhao, T. Quadrotor cascade control system design based on linear active disturbance rejection control. Appl. Sci. Basel 13, 6904 (2023).

Rigatos, G. et al. Flatness-based control in successive loops for autonomous quadrotors. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 146, 2 (2023).

Rigatos, G. et al. Nonlinear optimal control for free-floating space robotic manipulators. Spacecraft Satellite 1, 563 (2024).

Rigatos, G. et al. Nonlinear optimal control for a gas compressor driven by an induction motor. Results Control Optimiz. 11, 10029 (2023).

Zhang, X., Chen, C., Su, K., Lin, L. & Tian, Y. Design of the outdoor cruising control system of the quadrotor drone. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Env. Sci. 632, 022062 (2021).

Ye, H. et al. An experiment implementation of outdoor formation flight. In 2018 IEEE 8th Annual International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER) 93–98 (2018).

Liang, J. H. et al. A hierarchical control of independently driven electric vehicles considering handling stability and energy conservation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9, 738–751 (2024).

Liang, J. H. et al. An energy-oriented torque-vector control framework for distributed drive electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrif. 9, 4014–4031 (2023).

Leal Dopes, V. M. et al. Design of an over-actuated hexacopter tilt-rotor for landing and coupling in power transmission lines. Drones 7, 6 (2023).

Scomazzon, E. Closed loop identification and simulation of an octacopter drone. In Handle Proxy (2020–2021).

AbdulSamed, B., Aldair, A. & Al-Mayyahi, A. Robust trajectory tracking control and obstacles avoidance algorithm for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 15, 855–868 (2020).

Qi, Y. H. et al. Autonomous landing solution of low-cost quadrotor on a moving platform. Robot. Autonom. Syst. 119, 64–76 (2019).

Qiao, Z. et al. Simulation of a quadrotor under linear active disturbance rejection. Appl. Sci. 12, 12455–12455 (2022).

Alanezi, A. M. et al. Obstacle avoidance-based autonomous navigation of a quadrotor system. Drones 6, 288–288 (2022).

Ashtari, A., Stevsic, S., Nägeli, T., Bazin, J. & Hilliges, O. Capturing subjective first-person view shots with drones for automated cinematography. ACM Trans. Graph. 39, 159 (2020).

Bhargavapuri, M., Sahoo, S., Kothari, M. & Abhishek, K. Robust nonlinear control of a variable-pitch quadrotor with the flip maneuver. Control Eng. Pract. 87, 26–42 (2019).

Dong, J. & He, B. Novel fuzzy pid-type iterative learning control for quadrotor uav. Sensors 19, 24 (2018).

Noordin, A., Basri, M. A. M., Mohamed, Z. & Lazim, I. M. Adaptive PID controller using sliding mode control approaches for quadrotor UAV attitude and position stabilization. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 1–19 (2020).

Abdulsalam, N. A., Ibraheem, K. I. H. A. J. & Taher, A. Output tracking and feedback stabilization for 6-DoF UAV using an enhanced active disturbance rejection control. Int. J. Intell. Unmanned Syst. 10, 330–345 (2022).

Rao, J. J., Li, B., Zhang, Z., Chen, D. D. & Giernacki, W. Position control of quadrotor UAV based on cascade fuzzy neural network. Energies 15, 1763–1763 (2022).

Madruga, S., Tavares, A., Luiz, S., Nascimento, T. & Lima, A. Aerodynamic effects compensation on multirotor uavs based on a neural network control allocation approach. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 9, 295–312 (2021).

Chang, C., Chen, S., Wen, C. & Li, B. An actuator allocation method for a variable-pitch propeller system of quadrotor-based uavs. Sensors 20, 5651 (2020).

Santos, V., Honorio, L., Moreira, A., Silva, M. & Vidal, V. Fast real-time control allocation applied to over-actuated quadrotor tilt-rotor. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 102, 65 (2021).

Przenioslo, L. & Holub, M. Efficient electronic speed controller algorithm for multirotor flying vehicles. In 2018 Innovative Materials and Technologies in Electrical Engineering (iMITEL) 1–6 (2018).

Mosalsal, M. & Khodabandeh, M. Variable pitch control of a quadrotor using adaptive sliding mode controller. Aircraft Eng. Aerospace Technol. 95, 246–264 (2023).

Ryll, M. et al. 6d interaction control with aerial robots: The flying end-effector paradigm. Int. J. Robot. Res. 38, 1045–1062 (2019).

Brescianini, D. & D’Andrea, R. Design, modeling and control of an omni-directional aerial vehicle. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 3261–3266 (2016).

Dyer, E., Sirouspour, S. & Jafarinasab, M. Energy optimal control allocation in a redundantly actuated omnidirectional uav. In 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 5316–5322 (2019).

Islam, M., Okasha, M. & Sulaeman, E. A model predictive control (mpc) approach on unit quaternion orientation based quadrotor for trajectory tracking. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 17, 2819–2832 (2019).

Bingöl, Ö. & Güzey, M. Neuro sliding mode control of quadrotor uavs carrying suspended payload. Adv. Robot. 35, 255–266 (2021).

Tomic, T., Ott, C. & Haddadin, S. External wrench estimation, collision detection, and reflex reaction for flying robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. 33, 1467–1482 (2017).

Darby, C., Hager, W. & Rao, A. V. An hp-adaptive pseudospectral method for solving optimal control problems. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 32, 476–502 (2011).

Mark, C. H. J. P. Analysis and control of a variable-pitch quadrotor for agile flight. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 137, 10 (2015).

Lee, T., Leok, M. & McClamroch, N. H. Geometric tracking control of a quadrotor UAV on SE(3). In 49th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) 15–17 (2010).

Shang, B., Liu, J. X., Zhao, T. B. & Chen, Y. Q. Fractional Order Robust Visual Servoing Control of A Quadrotor UAV with Larger Sampling Period (2016).

Timis, D. D., Muresan, C. I. & Dulf, E. H. Design and experimental results of an adaptive fractional-order controller for a quadrotor. Fract. Fract. 6, 204–204 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.: Writing—Original Draf, Investigation, Formal analysis. C.Z.: Methodology, Review & Editing, Validation, Project administration. W.Y.: Programming, Review & Editing, Validation. S.Z.: Programming, Literature & Format Modification.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Cai, Z., Wang, Y. et al. The control method of a quadrotor driven by bidirectional electronic speed controllers. Sci Rep 14, 19532 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70681-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70681-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nonfragile Finite-time Contractive Control of a Quadrotor for Trajectory Tracking

International Journal of Control, Automation and Systems (2025)