Abstract

Changes in species diversity of different taxa along environmental gradients are usually correlated, resulting in a pattern called cross-taxon congruence. This pattern can be due to functional relationships between taxa, a common response to niche-related processes, or stochastic processes. However, it remains unclear the extent to which they contribute to the association among patterns of changes in species composition, (i.e., beta diversity), and whether these changes are related to species nestedness and turnover. Here we described patterns of change in the taxonomic composition of plant and orthopteran assemblages along an elevational gradient in Cordoba province, central Argentina. We assessed cross-taxon congruence and identified the main environmental variables accounting for such patterns. Mantel correlations showed congruence between the patterns of taxonomic dissimilarity of plants and orthopterans. According Generalized disiimilarity models (GDM) the main environmental variables driving the patterns were temperature for both taxa, and changes in soil nutrient content for plants, spatial effects were also found. Beta diversity was mainly due to species turnover for orthopterans and plants, indicating replacement by species adapted to elevational conditions. Niche-related process, such as environmetal filtering, along with neutral processes may have contributed to cross-taxon congruence in beta diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of the concordance between the diversity patterns of different taxa is of great importance for understanding the drivers of species distribution1,2. In particular, the existence of cross-taxon congruence patterns has been documented in several studies mainly focused on species richness3,4. Moreover, the analysis of cross-taxon congruence has important implications for conservation ecology due to the possibility of using indicator taxa for biodiversity monitoring purposes1,5. However, only a few studies have jointly considered cross-taxon congruence and its key underlying processes6,7. Changes in species composition, or beta diversity, may reveal patterns that are not necessarily evident through specific richness8, or alpha diversity. In general terms, it has been proposed that the assemblage of species at a given site is determined by a combination of stochastic processes, such as their dispersal abilities9, and environmental filtering driven by biotic interactions and abiotic conditions10. Furthermore, it was postulated that species can only occur within the range of environmental conditions aligning with their ecological niche11. The degree of differentiation between assemblages of a given taxonomic group may also be influenced by changes in the species composition of another taxonomic group12. For example, plants are at the base of terrestrial food webs constituting important feeding resources for animals13 and therefore the congruence between plant and animal diversity patterns could indeed be functional, but either due to trophic relationships or to selection by varying habitat structures (and both are not mutually exclusive). Thus, the beta diversity patterns among taxa are expected to show a certain degree of congruence driven either by a common response to environmental factors or by functional relationships between them.

Temporal and spatial changes in species composition can be deeply understood by partitioning beta diversity into two non-exclusive phenomena, nestedness and species turnover14. The concept of nestedness was formulated in the context of the island biogeography theory, where smaller assemblages (i.e., with lower species richness) are a subset of larger assemblages (i.e., with higher species richness)15. The proposed mechanisms responsible for this pattern are related with differential extinction16, differential colonization, and nested distribution of habitats17. On the other hand, species turnover is generated by the replacement of some species with others, giving rise to assemblages composed of new species14,18 along an environmental gradient. Distinguishing between these phenomena provides deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying biodiversity patterns19,20. The study of how spatial species nestedness and turnover of assemblages influence beta-diversity patterns has gained increasing attention since 2010 with Baselga’s Works14,21. Moreover, the identification of the processes involved in the differentiation of two communities (i.e., changes in taxonomic composition) is important for designing effective conservation strategies22. Therefore, if nestedness is primarily responsible for the variation between communities, then conservation priority should be given to a single large area of high species richness17, while if turnover is the dominant cause, several areas, typically containing more species, should be prioritized.

Elevational gradients usually reflect broad-scale geographic gradients of biodiversity23, and represent useful systems to investigate the causes and mechanisms driving spatial changes in biodiversity24,25. Although there is consensus that the degree of pattern congruence increases with scale2, the relative importance of the processes underlying cross-taxon congruence in species composition still remains unclear. The objectives of the present study were: to assess the degree of congruence between the beta diversity patterns of plants and herbivorous insects (i.e., orthopterans), to identify potentially associated environmental variables, and to study the process (species turnover or loss/gain) that most likely contributed to the observed pattern of beta diversity. Specifically, we: (1) described the patterns of change in the taxonomic composition of orthopteran and plant assemblages along an elevational gradient; (2) explored the association between changes in the composition of both taxa (congruence of patterns); (3) determined the main variables (e.g., geographic distance, temperature, humidity, and primary productivity) accounting for elevational changes in the taxonomic composition of orthopteran and plant assemblages; and (4) analyzed turnover and nestedness to better understand the drivers of change in assemblage composition.

Materials and methods

Study area

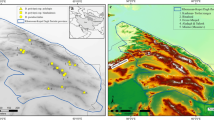

The study was conducted in Sierras Grandes, which is one of the four mountain ranges comprising the Sierras de Córdoba; these are located in the central-northwestern region of Córdoba province, Argentina, extending in a north-south orientation. The highest peaks are Cerro Champaquí (2884 masl) and Cerro Los Gigantes (2380 masl) and the mean maximum elevation is about 2000 masl. The Climate is sub-humid, with a tendency toward mountainous semiarid26. The rainy season lasts from September to March and the mean annual rainfall is 700–800 mm. Precipitation increases with elevation, with a mean annual value of 900 mm27. Mean annual temperatures in the lowlands and highlands are 14 and 8 °C, respectively, with no frost-free period28.

Sampling design

General design

To assess the possible mechanisms shaping spatial diversity patterns of plant and herbivorous arthropod assemblages, we explored a possible relationship between these patterns and the joint influence of different predictive variables along elevational gradients. The study was carried out on the western slope, where we selected three elevational trails (hereafter referred to as mountains), establishing sampling sites at 100-m intervals from the base to the top of each trail (See supp. 1). The gradients extended from Ambul to Pampa de Achala, in the Cerro Los Gigantes area; from Mina Clavero to Pampa de Achala, in the Cerro Trinidad area; and from Los Hornillos to Cerro Ventana area. There were a total of 34 sampling sites, of which 12 were set along one mountain and 11 along each of the other two mountains. At every sampling site we surveyed the plants, collected the orthopterans and measured the environmental variables relevant for these groups4 as described below. Permissions for collecting plants and orthopterans was obtained from Área de Recursos Naturales, Secretaría de Ambiente de la Provincia de Córdoba, according to the proper legislation.

Orthoptera sampling

Orthopterans were used as a model taxon of herbivorous arthropods because they are generalist folivores29. Even most grasshoppers are polyphagous (i.e., diet generalists), previous studies have found associations between plant communities and some orthopteran species30,31. These were collected using 38-cm diameter sweep nets, along a 50-m transect randomly placed at each site, 50 strokes were made on herbaceous and shrubby vegetation up to a height of 1.5 m, as stated in previous published work4. At each site, sampling was carried out at three different times of the day to prevent bias in the collection of specimens32. In the laboratory, specimens of Orthoptera were separated from the rest of the material and identified to species or morphospecies level, including nymphs when possible.

Plant sampling

To analyze plant diversity along the gradient, three quadrats of 1 × 1 m for herbs and 4 × 4 m for woody plants were randomly placed at each site in summer4. A minimum distance of 3 m was maintained between quadrats. All the vascular plants present were identified in the field to species/morphospecies level, and their cover-abundance was estimated according to the Braun-Blanquet method proposed by Kent33. The material that could not be taxonomically identified was taken to the laboratory for further analysis. Plant taxonomic classification was carried out using the Catalogo de Plantas Vasculares del Cono Sur34 and the online update (at http://www.darwin.edu.ar).

Estimation of environmental variables

At each site, we considered factors related to climatic conditions and soil characteristics as the most important variables accounting for the distribution of the studied groups4 (Table 1). Mean summer temperature was obtained from WorldClim V.II35. The mean normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was estimated from Landsat 8 (OLI) satellite images by averaging data from the summers of the sampling year and the previous one. A 2 × 2 pixel window was used, as the use of a group of pixels improves the correlation of NDVI with NPP compared to pixel-level estimates. The bands of this satellite needed to calculate NDVI were acquired with a spatial resolution of 30 × 30 m2. Additionally, we obtained the mean of the standard deviation of each date of the NDVI to account for vegetation heterogeneity. Topographic heterogeneity was quantified by extracting the slope from a digital elevation model (DEM) with a resolution of 30 × 30 m236, followed by the calculation of the terrain ruggedness index (TRI)37, with the spatial resolution of the DEM. All grid variables were calculated using QGis software38. Soil water content, defined as the mass of water per mass of dry soil, was determined from a sample of the top 10 cm of soil39. Finally, we determined the physical-chemical properties of the Soil at the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (Instituto del Suelo, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria). These properties included pH, electrical conductivity, water saturation percentage, carbon content, organic carbon, organic nitrogen, and total phosphorus. At each site three samples, from the top 10 cm of soil were collected and mixed before analysis. These soil characteristics were summarized in a single synthetic nutrient content variable that accounted for high positive correlations among all nutrient-related variables; this variable was created by retaining the first component of a principal component analysis (PCA) (Supp. 2).

Data analysis

We used dissimilarity indices to assess changes in the composition of orthopteran and plant species. A site x species matrix was generated for each taxon; these included sites with at least one species and species with incidence higher than one40. In addition, a separate matrices containing dissimilarity data on elevation, geographic position, and environmental variables was constructed. Sorensen index was used to computed dissimilarities of the composition for both taxa, the bray-curtis index for environmental distances and Euclidean distance for geographic distance. Geographic coordinates were previously projected onto a planar coordinate system (POSGAR2007 faja 4; EPSG:5346).

To evaluate the shape of the elevational pattern of differentiation between all pairs of sites, species dissimilarity was determined by the Sorensen index and the elevational distance by a euclidean distance. Then, the trend of the changes in the composition of orthopteran and plant assemblages along the elevational gradient were visually evaluated using scatter plots for each taxon, with species dissimilarity against the elevational distance. Mantel test was used to quantify the extent to which the dissimilarity patterns were congruent and mantel partial correlations was used to account for the spatially structured correlation. The significance level of each Mantel statistic was determined by comparing the observed value of r with those obtained after 9999 Monte Carlo simulations. Analyses were performed with R41. In particular, distance measures were estimated using the vegdist function of the R-package vegan42. Mantel Tests were conducted using the test implemented in the function mantel and mantel.partial from R-package vegan42.

A generalized disimilarity model (GDM)43,44 and model selection-based aproach was applied to analyze the extent to which the beta diversity pattern of both taxa can be described by environmental dissimilarity. GDM is particularly usefull to account for nonlinearity response of beta diversity to environmental gradients45,46, and is being increasingly applied to investigate biotic dissimilarity patterns and the environmental and geographical drivers46. Two GDM sets were constructed, one for orthopterans and the other for plants. Taxonomic dissimilarity was the response variable of each set, overall environmental dissimilarity (for all the environmental variables together) and individual environmental dissimilarity (for each environmental variable) were used as explanatory variables, always one dissimilarity variable at a time. Also geographic distance was included in the models. The default of three i-spline basis functions per predictor was used45,46. We ranked the models for each taxon according to the Akaike information criterion and the most informative sets of models were selected (delta AIC < 2). Models were implemented in R software41 with the package gdm44 using the functions formatsitepair, gdm and gdm.varImp, and the AIC function publicly available in Mokany et al.46.

To evaluate the relative contribution of the turnover and nestedness components to spatial changes in species composition, the Sorensen index was used to quantify total dissimilarity, the Simpson index to quantify the dissimilarity due to species replacement (turnover component) and their difference to quantify the dissimilarity due to species loss/gain (nestedness component)14,21. A mantel correlation test between each component (i.e. turnover and nestedness) and the total dissimilarity was used to evaluate which of the two components explained a larger proportion of total variation in beta diversity.

Results

The general trend of the dissimilarity in the composition of orthopteran and plant species showed an increasing pattern with increasing elevational distance between sites (Fig. 1). There was congruence between the dissimilarity patterns of these taxa, with a mantel correlation coefficient of 0.24 (p < 0.05). When controlling for spatial structure, the partial mantel correlation coefficient was 0.19 (p < 0.05).

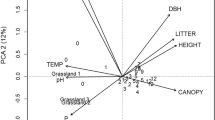

The most informative sets of models to explain the dissimilarity of orthopteran assemblages were selected (delta AIC < 2) (Table 2). This includes a model with both temperature dissimilarity and geographic distance (Fig. 2a), and also a model only with temperature dissimilarity (Fig. 2b). Temperature showed two zones of stteper slopes, one at the lowest and another at the higest temperature values, suggesting that the greatest compositional dissimilarity is in assemblages at the base and at and the top of the mountain, repectively (Fig. 3). For geographic distance we can observed an area with a proporcional increased in dissimilarity with distance that reaches a plateau at some distance (Fig. 3).

Orthopteran observed dissimilarity vs GDM-predicted ecological distance, points are each site pair, the line indicating the model predicted dissimilarity (left) and Observed dissimilarity vs. GDM-predicted dissimilarity, featuring the line of equality for reference (right). (a) Model with temperature dissimilarity and geographic distance; (b) model with temperature dissimilarity.

For plants, the assemblages dissimilarity are best explained by three models, two of these models included dissimilarity in soil nutrient component, with and without geographic distance. The third model included dissimilarity in temperature and geographic distance (Table 2; Fig. 4). For the model including soil nutrient component, fitted spline functions for these predictor variables showed a high composition dissimilarity once a threshold for soil nutrient component was exceeded. In contrast, the composition dissimilarity change across all distances encompassed by the study (Fig. 5a). For the model that included temperature dissimilarity, the predicted response of composition dissimilarity to geographical distance was strongest at shorter distances, while the response to temperature showed a threshold at the higest temperatures. This suggest that at hight temperatures (i.e. low altitudes), communities exhibit more dissimilarities in composition (Fig. 5b). The spline function patterns of the partial regression fits were consistent with those obtained when the same variable was modeled individually.

Orthopteran GDM fitted spline functions for the predictor variables included in the model with lowest AIC. On the x-axis, variables are in their native scales and on the y-axis, the transformed GDM values. The overall importance of each predictor is indicated by the maximum value of the spline function (y-axis). Steeper slopes indicate greater dissimilarity per unit change in the predictor variable.

Plant observed dissimilarity vs GDM-predicted ecological distance, points are each site pair, the line indicating the model predicted dissimilarity (left) and Observed dissimilarity vs. GDM-predicted dissimilarity, featuring the line of equality for reference (right). (a) Model with soil nutrient component dissimilarity; (b) Model with soil nutrient component dissimilarity and geographic distance; (c) model with temperature dissimilarity.

Plants GDM fitted spline functions for the predictor variables included in the models with lowest AIC. On the x-axis, variables are in their native scales and on the y-axis, the transformed GDM values. The overall importance of each predictor is indicated by the maximum value of the spline function (y-axis). Steeper slopes indicate greater dissimilarity per unit change in the predictor variable.

For orthopterans, the turnover component explained a larger proportion of total variation in plant composition (Table 3). Plants showed the same result, with turnover making a larger contribution to taxonomic dissimilarity (Table 3).

Discussion

The dissimilarity in the taxonomic composition of orthopterans and plants increased with the elevational distance between them. Clear patterns of increasing dissimilarity in species composition with geographic distance9,47 and with elevational distance have been observed both for plants48,49,50 and orthopterans51,52, in accordance with what is known as the Tobler’s first law of geography. Moreover, Ramos et al.4 found congruence between both richness patterns, albeit to a moderate degree (i.e., between 0.5 and 0.74). Other authors have also reported congruence levels of similar magnitude between patterns of beta diversity for plants and some arthropod groups in elevational gradients. Specifically, between the community of butterflies and the community of plants in mountain meadows8, or carabids and vascular plants in mountain ranges of China6 and even for insect community estimated from metabarcoded Malaise-trap samples and vascular plants53. These taxa encompass a diverse array of species, each engaging in distinct functional relationships with plants. For instance, butterflies, despite not being explicitly mentioned by the authors, are recognized as both pollinators and herbivores. On the other hand, carabids are primarily predatory insects, comprising granivorous and omnivorous species6. The possibility of biotic and abiotic relationships is proposed in all study cases, but only Duan et al.6 analyzes both possibilities, finding, despite controlling for many environmental variables, a relationship between carabids and plant diversity, which he proposes could be due to issues related to the history of anthropic use that were not considered. We found than the detected congruence between orthopterans and plants likely evidence a common response to the same environmental variable, rather than a functional relationship between them. Therefore, evidence suggests that the use of indicator taxa may have a limited utility4 and that their use should be assessed in each case5. Reported congruence levels are often low or moderate, also the underlying causes of these patterns can vary and these may become decouple in the face of environmental change.

The analysis of the overall environmental dissimilarity (considering all the environmental variables together) did not explain the dissimilarity in assemblage composition for any of the studied groups. This was probably due to the fact that those environmental variables together would not reflect key factors affecting species survival and establishment or to the fact that the response could not be detected at the scale of the study. In regard to the latter hypothesis, it has been proposed that local species assemblages are shaped by hierarchical ‘filters’ operating at different spatial scales54. A complementary study at the scale of the site will help elucidate this possibility.

The dissimilarity in the orthopteran assemblage increased with increasing dissimilarity in temperature between sites, suggesting the importance of this factor in determining the species present at each site. Orthopterans are greatly affected by temperature and previous studies conducted in elevational gradients have suggested that only species with particular reproductive traits thrive in colder environments, such as those having a univoltine strategy55 and ovipositing on vegetation instead of on soil52. Jointly with temperature dissimilarity, distance effects were also detected, a common response for many groups of arthropods in environmental gradients56. Changes in orthopteran species composition along the gradient may be linked to both physiological constraints determining tolerance ranges (thermal in our case) of species and, a combination of stochastic processes, such as their dispersal abilities or by unmeasured spatially structure factors.

Plant assemblage change was found to be related with the dissimilarity in soil nutrient content with or without considering spatial effects. Soil chemical changes has been reported to explain beta diversity patterns in regional studies for plants57,58 and also in mountain ranges59 Albeit in mountains, it has been reported that climatic effects are more common60. Also, the dissimilarity in plant community composition can be explained by dissimilarity in temperature between sites jointly with geographic distance. A previous study conducted in the same elevational gradient as ours has already suggested a possible response to temperature by the plant assemblage61. Moreover, the influence of temperature on the beta diversity patterns of plants was also observed in other elevational gradients48. Temperature has been reported to be a limiting factor for species distribution in mountainous zones62. Such response may reflect plant adaptations to different environmental conditions determined by their thermal tolerance. For example, low temperature causes metabolic lethargy and free radical accumulation leading to oxidative stress or even freezing of cell water63. On the other hand, changes in temperature along the gradient may affect competition interactions between plants according to their tolerance ranges to temperature64.

Turnover appeared as the dominant component driving the dissimilarity pattern of the ortopteran and plant community, indicating that the differentiation in these communities along the gradient was mostly due to species replacement. This result is in agreement with previous studies for plants in the tropical Andes65. Moreover, turnover was suggested as the primary component of beta diversity along latitudinal gradients for different taxa66. Therefore, environmental change along elevational and latitudinal gradients provides some species with new environmental conditions for their establishment, while species with specialized niche requirements are eliminated67. From an applied approach, efforts for plant conservation in Sierras de Córdoba should consider the whole gradient. A similar conclusion was drawn in a study of an elevational gradient in the European Alps68. Although finding congruence in the elevational pattern of changes in species composition, the present study emphasizes the need to consider the components of beta diversity to better implement conservation strategies along elevational gradients.

Data availability

Relevant raw data is available online in previously published paper, see: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-83763-3#Sec12.

References

Gioria, M., Bacaro, G. & Feehan, J. Evaluating and interpreting cross-taxon congruence: Potential pitfalls and solutions. Acta Oecologica 37, 187–194 (2011).

Rooney, R. C. & Azeria, E. T. The strength of cross-taxon congruence in species composition varies with the size of regional species pools and the intensity of human disturbance. J. Biogeogr. 42, 439–451 (2015).

McKnight, M. W. et al. Putting beta-diversity on the map: Broad-scale congruence and coincidence in the extremes. PLoS Biol. 5, 2424–2432 (2007).

Ramos, C. S., Picca, P., Pocco, M. E. & Filloy, J. Disentangling the role of environment in cross-taxon congruence of species richness along elevational gradients. Sci. Rep. 11, 4711 (2021).

Westgate, M. J., Barton, P. S., Lane, P. W. & Lindenmayer, D. B. Global meta-analysis reveals low consistency of biodiversity congruence relationships. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–8 (2014).

Duan, M. et al. Disentangling effects of abiotic factors and biotic interactions on cross-taxon congruence in species turnover patterns of plants, moths and beetles. Sci. Rep. 6, 2–10 (2016).

Uboni, C. et al. Exploring cross-taxon congruence between carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) and vascular plants in sites invaded by Ailanthus altissima versus non-invaded sites: The explicative power of biotic and abiotic factors. Ecol. Indic. 103, 145–155 (2019).

Su, J. C., Debinski, D. M., Jakubauskas, M. E. & Kindscher, K. Beyond species richness: Community similarity as a measure of cross-taxon congruence for coarse-filter conservation. Conserv. Biol. 18, 167–173 (2004).

Nekola, J. C. & White, P. S. The distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology. J. Biogeogr. 26, 867–878 (1999).

Kraft, N. J. B. et al. Community assembly, coexistence and the environmental filtering metaphor. Funct. Ecol. 29, 592–599 (2015).

Soininen, J., McDonald, R. & Hillebrand, H. The distance decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecography 30, 3–12 (2007).

Jiménez-Alfaro, B., Chytrý, M., Mucina, L., Grace, J. B. & Rejmánek, M. Disentangling vegetation diversity from climate-energy and habitat heterogeneity for explaining animal geographic patterns. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1515–1526 (2016).

Kissling, W. D., Field, R. & Böhning-Gaese, K. Spatial patterns of woody plant and bird diversity: Functional relationships or environmental effects?. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 327–339 (2008).

Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 134–143 (2010).

Ulrich, W., Almeida-Neto, M. & Gotelli, N. J. A consumer’s guide to nestedness analysis. Oikos 118, 3–17 (2009).

Doak, D. F. & Mills, L. S. A useful role for theory in conservation. Ecology 75, 615–626 (1994).

Boecklen, W. J. Nestedness, biogeographic theory, and the design of nature reserves. Oecologia 112, 123–142 (1997).

Koleff, P., Gaston, K. J. & Lennon, J. J. Measuring beta diversity for presence-absence data. J. Anim. Ecol. 72, 367–382 (2003).

Brendonck, L., Jocqué, M., Tuytens, K., Timms, B. V. & Vanschoenwinkel, B. Hydrological stability drives both local and regional diversity patterns in rock pool metacommunities. Oikos 124, 741–749 (2015).

Gianuca, A. T., Declerck, S. A. J., Lemmens, P. & De Meester, L. Effects of dispersal and environmental heterogeneity on the replacement and nestedness components of beta-diversity. Ecology 98, 525–533 (2017).

Baselga, A. & Orme, C. D. L. Betapart: An R package for the study of beta diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 808–812 (2012).

Angeler, D. G. Revealing a conservation challenge through partitioned long-term beta diversity: Increasing turnover and decreasing nestedness of boreal lake metacommunities. Divers. Distrib. 19, 772–781 (2013).

Fosaa, A. M. Biodiversity patterns of vascular plant species in mountain vegetation in the Faroe Islands. Divers. Distrib. 10, 217–223 (2004).

Körner, C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 569–574 (2007).

McCain, C. M. & Grytnes, J.-A. Elevational gradients in species richness. Encycl. Life Sci. 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0022548 (2010).

Giorgis, M. A. et al. Composición florística del Bosque Chaqueño Serrano de la provincia de Córdoba, Argentina. Kurtziana 36, 9–43 (2011).

Acosta, A., Diaz, S., Menghi, M. & Cabido, M. Patrones comunitarios a diferentes escalas espaciales en pastizales de las Sierras de Córdoba, Argentina. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 65, 195–207 (1992).

Cabido, M., Funes, G., Pucheta, E., Vendramani, F. & Díaz, S. A chorological analysis of the mountains from Central Argentina. Is all what we call Sierra Chaco really Chaco? Contribution to the study of the flora and vegetation of the Chaco: 12. Candollea 53, 321–331 (1998).

Hodkinson, I. D. & Hughes, M. K. Insect Herbivory Vol. 15 (Chapman and Hall, 1982).

Masloski, K., Greenwood, C., Reiskind, M. & Payton, M. Evidence for diet-driven habitat partitioning of melanoplinae and gomphocerinae (Orthoptera: Acrididae) along a vegetation gradient in a western Oklahoma grassland. Environ. Entomol. 43, 1209–1214 (2014).

Torrusio, S., Cigliano, M. M. & Wysiecki, M. L. Grasshopper (Orthoptera: Acridoidea) and plant community relationships in the Argentine Pampas. J. Biogeogr. 29, 221–229 (2002).

Southwood, T. R. E. The components of diversity. in Symp. R. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 9 (eds. Mound, L. A. & Waloff, N.) 19–44 (Blackwell, Oxford, 1978).

Kent, M. The description of vegetation in the field. In Vegetation Description and Data Analysis: A Practical Approach 65–116 (Wiley, 2012).

Catálogo de Las Plantas Vasculares Del Cono Sur: (Argentina, Sur de Brasil, Chile, Paraguay y Uruguay). (Missouri Botanical Garden Press, 2008).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

IGN. Modelo Digital de Elevaciones de La República Argentina. (Instituto Geográfico Nacional - Dirección General de Servicios Geográficos - Dirección de Geodesia, Buenos Aires, 2016).

Riley, S. J., DeGloria, S. D. & Elliot, R. A terrain ruggedness index that quantifies topographic heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 5, 23–27 (1999).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. (2023).

Aisen, S., Werenkraut, V., Márquez, M. E. G., Ramírez, M. J. & Ruggiero, A. Environmental heterogeneity, not distance, structures montane epigaeic spider assemblages in north-western Patagonia (Argentina). J. Insect Conserv. 21, 1–12 (2017).

Jongman, R. H. Data Analysis in Community and Landscape Ecology (Cambridge University Press, 1995). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511525575.

R Core Team. R version 3.6.2 ‘Dark and Stormy Night’. https://www.r-project.org (2019).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2.6-6.1 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan (2022).

Ferrier, S., Manion, G., Elith, J. & Richardson, K. Using generalized dissimilarity modelling to analyse and predict patterns of beta diversity in regional biodiversity assessment. Divers. Distrib. 13, 252–264 (2007).

Fitzpatrick, M., Mokany, K., Manion, G., Nieto-Lugilde, D. & Ferrier, S. gdm: Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling. 1.5.0-9.1 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.gdm (2022).

Fitzpatrick, M. C. et al. Environmental and historical imprints on beta diversity: Insights from variation in rates of species turnover along gradients. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280, 20131201 (2013).

Mokany, K., Ware, C., Woolley, S. N. C., Ferrier, S. & Fitzpatrick, M. C. A working guide to harnessing generalized dissimilarity modelling for biodiversity analysis and conservation assessment. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 802–821 (2022).

Qian, H. & Ricklefs, R. E. A latitudinal gradient in large-scale beta diversity for vascular plants in North America. Ecol. Lett. 10, 737–744 (2007).

Tang, Z. et al. Patterns of plant beta-diversity along elevational and latitudinal gradients in mountain forests of China. Ecography 35, 1083–1091 (2012).

Zhang, W., Huang, D., Wang, R., Liu, J. & Du, N. Altitudinal patterns of species diversity and phylogenetic diversity across temperate mountain forests of northern China. PLoS ONE 11, 1–13 (2016).

Buitrago-Guacaneme, A., Molineri, C., Cristóbal, L. & Dos Santos, D. A. The inter-forest line could be the master key to track biocoenotic effects of climate change in a subtropical forest. Biotropica 54, 57–70 (2022).

Rominger, A. J., Miller, T. E. X. & Collins, S. L. Relative contributions of neutral and niche-based processes to the structure of a desert grassland grasshopper community. Oecologia 161, 791–800 (2009).

Fournier, B., Mouly, A., Moretti, M. & Gillet, F. Contrasting processes drive alpha and beta taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity of orthopteran communities in grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 242, 43–52 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. Plant diversity accurately predicts insect diversity in two tropical landscapes. Mol. Ecol. 25, 1–35 (2016).

de Bello, F. et al. Hierarchical effects of environmental filters on the functional structure of plant communities: A case study in the French Alps. Ecography 36, 393–402 (2013).

Betina, S. I., Harrat, A. & Petit, D. Analysis of factors involved in grasshopper diversity in arid Aurès mountains (Batna, Algeria). J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 5, 339–348 (2017).

González-Reyes, A. X., Corronca, J. A. & Rodriguez-Artigas, S. M. Changes of arthropod diversity across an altitudinal ecoregional zonation in Northwestern Argentina. PeerJ 5, e4117 (2017).

Jones, M. M. et al. Strong congruence in tree and fern community turnover in response to soils and climate in central Panama. J. Ecol. 101, 506–516 (2013).

Ulrich, W. et al. Climate and soil attributes determine plant species turnover in global drylands. J. Biogeogr. 41, 2307–2319 (2014).

Bryant, J. A. et al. Microbes on mountainsides: Contrasting elevational patterns of bacterial and plant diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 11505–11511 (2008).

Sánchez-González, A. & López-Mata, L. Plant species richness and diversity along an altitudinal gradient in the Sierra Nevada, Mexico. Divers. Distrib. 11, 567–575 (2005).

Giorgis, M. A. et al. Changes in floristic composition and physiognomy are decoupled along elevation gradients in central Argentina. Appl. Veg. Sci. 20, 553–571 (2017).

Antoine, G., Theurillat, J. P. & Kienast, F. Predicting the potential distribution of plant species in an alpine environment. J. Veg. Sci. 9, 65–74 (1998).

Beck, E. H., Heim, R. & Hansen, J. Plant resistance to cold stress: Mechanisms and environmental signals triggering frost hardening and dehardening. J. Biosci. 29, 449–459 (2004).

Gotelli, N. J. & Mccabe, D. J. Species co-occurrence: A meta-analysis of JM Diamond’s assembly rules. Ecology 83, 2091–2096 (2002).

Tolmos, M. L., Kreft, H., Ramirez, J., Ospina, R. & Craven, D. Water and energy availability mediate biodiversity patterns along an elevational gradient in the tropical Andes. J. Biogeogr. 49, 712–726 (2022).

Soininen, J., Heino, J. & Wang, J. A meta-analysis of nestedness and turnover components of beta diversity across organisms and ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12660 (2017).

Pérez-Toledo, G. R., Valenzuela-González, J. E., Moreno, C. E., Villalobos, F. & Silva, R. R. Patterns and drivers of leaf-litter ant diversity along a tropical elevational gradient in Mexico. J. Biogeogr. 48, 2512–2523 (2021).

Fontana, V. et al. Species richness and beta diversity patterns of multiple taxa along an elevational gradient in pastured grasslands in the European Alps. Sci. Rep. 10, 12516 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.R. and J.F. conceived the idea and designed the research. C.S.R., J.F. and M.V.L. conducted the fieldwork. C.S.R. analyzed the data and prepared figures. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos, C.S., Loetti, M.V. & Filloy, J. Understanding processes underlying cross-taxon congruence in species composition along elevational gradients. Sci Rep 14, 21698 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70782-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70782-z