Abstract

Organic matter in the Martian sediments may provide a key to understanding the prebiotic chemistry and habitability of early Mars. The Curiosity rover has measured highly variable and 13C-depleted carbon isotopic values in early Martian organic matter whose origin is uncertain. One hypothesis suggests the deposition of simple organic molecules generated from 13C-depleted CO derived from CO2 photochemical reduction in the atmosphere. Here, we present a coupled photochemistry-climate evolution model incorporating carbon isotope fractionation processes induced by CO2 photolysis, carbon escape, and volcanic outgassing in an early Martian atmosphere of 0.5–2 bar, composed mainly of CO2, CO, and H2 to track the evolution of the carbon isotopic composition of C-bearing species. The calculated carbon isotopic ratio in formaldehyde (H2CO) can be highly depleted in 13C due to CO2-photolysis-induced fractionation and is variable with changes in atmospheric CO/CO2 ratio, surface pressure, albedo, and H2 outgassing rate. Conversely, CO2 becomes enriched in 13C, as estimated from the carbonates preserved in ALH84001 meteorite. Complex organic matter formed by the polymerization of such H2CO could explain the strong depletion in 13C observed in the Martian organic matter. Mixing with other sources of organic matter would account for its unique variable carbon isotopic values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic matter in sediments on a planetary surface may provide a key to understanding prebiotic chemistry and habitability. The Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument onboard the Curiosity rover discovered organic matter in the early Martian sediment1. Moreover, a recent analysis discovered highly variable carbon isotopic compositions with δ13C values from − 137 ± 8 to + 22 ± 10‰ in organic matter in the early Martian sediments at Gale Crater2, notably indicating strongly 13C-depleted carbon whose origin is unknown. Potential sources and mechanisms to form such organics are electro-chemical reduction of CO2 in groundwater3,4, igneous refractory carbon (e.g., − 25 ± 5‰)5, exogenous supply by carbonaceous meteorites (e.g., −25 to − 4‰)6,7, and atmospheric synthesis through other energy inputs such as lightning, high-energy particles, and impact shock8. However, these mechanisms are unlikely to explain the strong isotopic depletion observed.

One of the potential mechanisms that could produce a strong depletion in 13C is the deposition of simple organic molecules generated from 13C-depleted CO derived from CO2 photolysis. Ueno et al.9 demonstrated that CO2 photolysis can yield strongly 13C-depleted CO based on photolysis experiments and theoretical consideration, as indicated by quantum theoretical calculations10. The 13C-depleted CO influenced by the photolysis-induced isotopic fractionation is observed in the present-day Martian atmosphere11,12,13 and Earth’s mesosphere14. Among possible organic molecules generated from the photolysis-derived CO, formaldehyde (H2CO), a highly soluble and reactive molecule, might have been efficiently and continuously formed in the early Martian atmosphere during the Noachian and early Hesperian periods15. Dissolved H2CO in water would subsequently form diverse organic matter, including sugars, amino acids, and complex organic matter, possibly by the formose-type reaction16,17. Although it is a thermally driven aqueous process, this reaction can proceed at moderate temperatures18. However, the quantitative investigation of photolysis-induced isotopic fractionation on organic molecules under early Martian atmospheric conditions has not been conducted.

The Martian atmosphere has undergone significant changes since its formation. Although it is currently a thin CO2-dominated atmosphere, Mars may have obtained a thick atmosphere enriched in H2, CH4, and CO through impact degassing from accreting materials as well as capture of solar nebula gas during the accretion phase19,20. Such a proto-atmosphere likely experienced extensive escape driven by the intense extreme ultraviolet (EUV) flux of the ancient Sun, with reduced molecules of CH4, oxidized into CO and CO221,22. Consequently, an atmosphere dominated by CO or CO2 with ~ 0.5–2 bars may have been formed23,24,25. Later, episodic warm climates may have occurred, as indicated by geomorphological and geochemical evidence during the late Noachian and early Hesperian periods at 3.8–3.6 Ga26. This study focuses on the early Martian atmosphere at ~ 4–3 Ga after the vigorous escape of C and H due to the strong EUV flux.

Results and discussion

Changes in δ13C values in H2CO during early Mars’ atmospheric evolution

We present a coupled photochemistry-climate evolution model that integrates carbon isotope fractionation effects induced by CO2 photolysis, carbon escape to space, and volcanic outgassing of CO and CO2 (see Method for details). This model calculates carbon isotope composition changes in H2CO and CO2 over time, beginning with an atmosphere mainly composed of 30% CO2, 69% CO, and 1% H2 at 4 Ga as a representative scenario. We assume a 2 bar atmosphere as a nominal condition that most likely enables the episodic melting scenarios during volcanic outgassing or meteorite impact events (S4 in Supplementary Information)27.

As a result, the atmosphere changes from CO-dominated to CO2-dominated over time (Fig. 1), driven by a positive feedback mechanism in CO2 formation. An increase in CO2 partial pressure, facilitated by the catalytic reaction between CO and OH, contributes to increases in the surface temperature by its greenhouse effect. This results in more H2O vapor originating from surface ice, controlled by saturation water vapor pressure, leading to increased OH production via H2O photolysis. The recombination of CO2 is thus further facilitated by the reaction between CO and OH.

Evolution of δ13C (upper panel) in CO2 and H2CO, mixing ratios of CO2, CO, and H2 (middle panel), and surface temperature (lower panel) for 1-bar (dashed line) and 2-bar (solid line) atmosphere, starting from 4 Ga. The initial atmosphere comprises mantle-derived 30% CO2, 69% CO, and 1% H2 with a δ13C of − 25 ‰. In the upper panel, the light gray band indicates the range of δ13C in organic matter in the early Martian sediments observed by Curiosity. The dark gray band indicates the range of δ13C in early atmospheric CO2 at 4–3.9 Ga estimated from ALH840019. The blue (H2CO) and orange (CO2) shaded regions in the upper panels include the uncertainty of the C escape fractionation factor (0.4–0.8) and the initial δ13C in the atmosphere (− 30 – − 20 ‰).

During the atmospheric evolution, the carbon isotopic ratio in H2CO decreases from the initial δ13C value (− 25 ± 5‰) to a minimum δ13C value of approximately − 200‰ (Fig. 1). The δ13C value in H2CO is identical to that in CO because the model assumes no isotopic fractionation during the reactions from CO to form H2CO, which is very likely to be negligible compared to the isotopic fractionation induced by CO2 photolysis9. The decrease in δ13C value in H2CO over the initial several hundred million years is attributed to the production, and increasing proportion of 13C-depleted CO derived from CO2 photolysis over total CO. After about 400 million years (Myr), the CO2 mixing ratio does not increase significantly, and the effect of photolysis-induced fractionation remains almost constant, keeping the δ13C value of H2CO nearly constant during the later stages of the evolution.

13C enrichment of CO2 due to the isotopic fractionation driven by its photolysis

The δ13C in CO2 increases over the initial 100 Myr due to more efficient photolysis of 12CO2 compared to 13CO2 (Fig. 1). However, this trend reverses after 100 Myr because of the relative weakening of the photolysis-induced fractionation effect with increased CO2 concentration, and because the relative ratio of photodissociated to non-photodissociated CO2 decreases with increasing the amount of total CO2. Consequently, δ13C in CO2 gradually decreases to the initial mantle-derived value over time. This model, focused on dense atmospheres (~ 0.5–2 bar), does not exhibit the positive slope in the δ13C evolution of CO2 from carbon escape, but such an effect will be observed at a more reduced stage of atmospheric pressure, leading to the current enriched carbon isotopic ration of CO224.

Several million years after the beginning of the model calculation, the δ13C in CO2 aligns with the δ13C range of early Martian atmospheric CO2 (+ 20 ± 10‰), estimated from the analysis of carbonates in ALH84001 meteorite that formed at 4–3.9 Ga9. This value is enriched in 13C compared to that in the Martian mantle (− 25 ± 5‰)28. The carbonate formation age (4–3.9 Ga) of the ALH84001 meteorite29 could be in the alignment time of the model calculation, given that the initial atmospheric composition of the model is 70% CO2, 29% CO, and 1% H2 (see Supplementary Information). These results suggest that isotopic fractionation resulting from CO2 photolysis contributed to the enrichment of 13C in the carbonates preserved in ALH84001 alongside carbon escape to space and volcanic outgassing. The alignment of the model CO2 isotopic composition with the timing of ALH84001 meteorite carbonate formation also depends on the model’s initial atmospheric settings including model’s starting time (Supplementary Information for details). The precise atmospheric composition at 4 Ga remains undetermined due to uncertainties such as the amount of volatiles delivered to accreting Mars, the mass of the proto-atmosphere derived from the solar nebula and degassing, and the timescale for the atmospheric escape20,21,22.

Effect of atmospheric pressure on the carbon isotope evolution

In atmospheres of 1 and 0.5 bar, CO concentration is higher than in the 2 bar nominal condition due to a weaker greenhouse effect under lower atmospheric pressures, which diminishes the positive feedback in CO2 formation catalyzed by odd hydrogen. In a 0.5 bar atmosphere, a negative feedback driven by H2O2 deposition also contributes to the result of higher CO concentration. As H2O vapor concentration increases, so does the production and subsequent deposition of H2O2. This process leads to atmospheric reduction through oxygen loss from the atmosphere, which, in turn, inhibits the recombination of CO2, maintaining a higher CO concentration.

After 500 Myr from the beginning, the 1 and 0.5 bar atmospheres have a higher δ13C value of H2CO than that of the 2 bar atmosphere by approximately 30 and 80‰, respectively. This is because the relative ratio of 13C-depleted CO derived from CO2 photolysis to CO derived from the mantle is lower under lower atmospheric pressures. The dependence of the δ13C values in H2CO and CO2 on the surface pressure is shown in Fig. 2. The δ13C value in H2CO, under conditions where the surface pressure exceeds 1 bar, falls below the lower limit of − 145‰ for the δ13C range in the early Martian organic matter. The decreasing rate from 1.5 to 2 bar atmosphere is attenuated, suggesting that the CO2 photolysis under approximately 2 bar atmosphere is close to saturated, and the minimum δ13C in the photochemically produced H2CO on early Mars is approximately − 200‰. Under 0.5 bar atmospheric pressure, however, the δ13C value in H2CO fits in Curiosity’s observation range, while that in CO2 exceeds the range of ALH84001’s carbonate during the entire evolution.

Changes in atmospheric pressure also affect planetary albedo, an important parameter that controls the energy balance in the atmosphere30. The planetary albedo is considered 0.2 as the standard case, referring to the present-day Martian value. We also ran the model for 0.5 and 2 bar atmospheres with a planetary albedo of 0.330 (Fig. 3). As a result, the positive feedback in CO2 formation catalyzed by odd hydrogen, is weakened due to the lower temperature with higher albedo, leading to a higher CO concentration of ~ 30% for the 2 bar atmosphere. The δ13C values in H2CO become higher and closer to the lower limit of Curiosity’s observation range than those with the standard albedo. The 0.5 bar atmosphere ends up with a state called CO runaway31,32, CO and O derived from CO2 photolysis no longer recombine due to the lack of OH to catalyze CO2 recombination in colder atmospheres with lower amounts of H2O vapor. The δ13C values in CO2 do not fit in the range of ALH84001’s carbonate during the evolution for both 0.5 and 2 bar cases with higher albedo. Additionally, the strong 13C depletion in H2CO is not observed in the 0.5 bar atmosphere with an albedo of 0.3. These findings suggest that a low atmospheric pressure of 0.5 bar and a high albedo of 0.3 are inconsistent with the observed data.

Effect of H2 outgassing on the carbon isotope evolution of H2CO

Variations in the H2 outgassing rate, which is highly uncertain on early Mars, alter the δ13C value in H2CO by approximately 40‰ for a 2 bar atmosphere. This variation is primarily influenced by the CO/CO2 ratio in the atmosphere (Fig. 4). The evolution of CO/CO2 atmospheres can be categorized into two distinct scenarios: 1) the atmosphere transitions to CO2-dominated at a high H2 outgassing rate (~ \(>\)1010 cm−2 s−1), and 2) the atmosphere maintains a certain amount of CO at low H2 outgassing rate (~ \(\le\)1010 cm−2 s−1). With a high H2 outgassing rate of 2 × 1011 cm−2 s−1, as estimated from the chemical equilibrium of the IW (iron-wüstite) buffer and used in the model’s nominal condition (See Supplementary Information), the atmosphere changes from CO-dominated to CO2-dominated over time (Fig. 1). This shift is driven by a positive feedback mechanism in CO2 formation, where additional H2 further accelerates this cycle by collision-induced absorption warming effect33, leading to more H2O vapor and recombination of CO2 from CO and OH in the atmosphere. Conversely, with the low H2 outgassing rate of 1 × 1010 cm−2 s−1, associated with the QFM (quartz–fayalite–magnetite) buffer34, the atmosphere maintains a CO concentration of 30–40%, resulting from the negative feedback driven by H2O2. In this scenario, the δ13C value in H2CO is about 40‰ higher than in the high H2 outgassing case because the relative ratio of depleted CO derived from CO2 photolysis to the absolute amount of CO is low due to the high CO/CO2 ratio in the atmosphere. This low H2 outgassing rate scenario could produce organic matter with a δ13C value closer to the observed minimum. Moreover, changes in the rate of H2 outgassing during Martian history could have led to different δ13C values in H2CO at different epochs.

δ13C in H2CO (upper panel) as a function of H2 outgassing rate. The lower panel shows the H2CO deposition flux (blue line) and the ratio of the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) to the sum of the partial pressure of CO2 and CO (black line). The plotted values are taken from the 2-bar results after 600 Myr from the start of calculations under various H2 outgassing rates. All other atmospheric conditions are the same as nominal conditions.

Implications for the origin of organic matter on Mars

The deposition flux of photochemically produced H2CO on early Mars was investigated thoroughly in Koyama et al.15, suggesting that H2CO is deposited at a rate of 1010–1011 mol yr−1 during the warm climate periods (3.8–3.6 Ga) when organic matter is most likely formed through the formose reaction. A few percent of this H2CO would convert to organic matter that contributes to the production of CH4 during the pyrolysis analysis of House et al.2 through the formose reaction17. Among other potential sources of organic matter from exogenous delivery, interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) are estimated to have been the most abundant on early Earth at a rate of ~ 107 kg carbon yr−1 (= 8 × 108 mol yr−1) at 3.8–3.6 Ga8. We estimated the flux of micrometeorite on early Mars to be ~ 108 mol yr−1 by scaling this IDPs flux on early Earth with the Martian smaller collision cross section 15,35. Therefore, the production of 13C-depleted organic matter derived from photochemically produced H2CO is comparable to or a few times larger than the flux of exogenous organic matter in terms of contribution to the production of CH4 during the pyrolysis analysis of House et al.2.

The δ13C value in H2CO is higher than − 140 ‰ for the first 100 Myr of 1–2 bar atmospheres (Fig. 1). This period corresponds to the ice-covered age in the early Noachian, where the atmosphere lacked sufficient CO2 to form a warm environment. In such an environment, H2CO, formed from a mixture of mantle-derived CO and 13C-depleted CO from CO2 photolysis, could accumulate in snow on the surface. H2CO, which absorbs considerable energy at wavelengths of ~ 250–350 nm36 that can reach the ground in early Mars conditions, would be protected from UV radiation by covered snow or silicate minerals after sediment incorporation. This stored H2CO with δ13C > − 140 ‰ could have dissolved into water bodies in episodically warm climates (see Supplementary Information), and then polymerize to form complex organic matter that is composed of aromatic and aliphatic carbon with δ13C values similar to those of H2CO17,37. This mechanism could also have facilitated a continuous supply of biologically important sugars during such transient warm periods on early Mars15. Note that our model neglects isotopic fractionation for H2CO degradation after deposition. The fractionation effect during H2CO photolysis is uncertain and should be further investigated in future experiment studies. The H2CO oxidation into CO2 only caused a small fractionation within 10‰9,13. Additionally, H2CO condensation into formose mixture does not modify carbon isotopic composition significantly due to mass conservation.

Furthermore, our results show that the minimum δ13C value in photochemically produced H2CO on early Mars is approximately − 200‰, which falls below the observation range (Fig. 1). Our model used the theoretically derived cross-sections for 13CO210. This may cause estimates of about 30‰ lower δ13C values, given the results of a reported validation experiment9. The 30‰-compensated minimum value of our results is closer to the minimum δ13C values reported as early Martian sedimentary organics, but still lower than that value (see Supplementary Information). Another potential uncertainty is that the initial δ13C value of our estimates may have been higher than the mantle-derived value (− 25 ± 5‰). If the strong EUV irradiation induces a significant loss of carbon21, the remaining carbon in the atmosphere would have a heavier carbon isotopic ratio22.

Considering this 13C depletion in photochemically produced H2CO and its significance in deposition flux, it is likely that this 13C-depleted organic matter (i.e., ~ − 170‰) was the lower end-member in δ13C values, and mixing with other sources of organics, such as meteorite, with higher δ13C values would lead to the observed low and variable δ13C values (i.e., − 137 ± 8 to + 22 ± 10‰) in Martian organic matter (Fig. 5). H2CO accumulated in snow during the ice-covered period could have also contributed to the variability observed in δ13C values during transient melting events. In any case, the photochemically produced 13C-depleted H2CO likely played a significant role in forming organic matter on early Mars.

Conclusions

We investigated the evolution of the carbon isotopic composition of C-bearing species throughout the atmospheric evolution of early Mars using a coupled photochemistry-climate model. The calculated carbon isotopic ratio in H2CO shows a significant depletion in 13C, resulting from the isotopic fractionation induced by CO2 photolysis. This ratio also varies with changes in the atmospheric background conditions, such as CO/CO2 ratio, surface pressure, albedo, and H2 outgassing rate. These findings imply that certain amounts of organic matter containing strongly depleted 13C in the early Martian sediment could have originated from the photochemically produced H2CO, undergoing subsequent condensation processes in water, such as formose-type reactions, during transient melting events during the late Noachian to Hesperian periods. Mixing with other organic sources, such as meteoritic material with higher δ13C values, would lead to the observed variable δ13C values in Martian organic matter. Furthermore, our results suggest that the isotopic fractionation induced by CO2 photolysis would also contribute to the enrichment of 13C in early Mars atmospheric CO2 estimated from the carbonates preserved in ALH84001 meteorite. To further understand the origins of organic matter on early Mars, constraints on carbon isotopic ratios across different epochs are essential. Future insights will come from NASA and ESA’s Mars Sample Return (MSR) missions and the Martian Moons eXploration (MMX)38,39, which aims to bring back samples from Phobos.

Methods

Photochemistry model

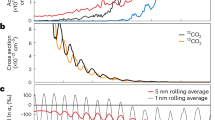

We have developed a photochemistry-climate coupled evolution model to calculate the evolution of carbon isotope composition in H2CO, CO, and CO2 in the early Martian atmosphere. We implement the carbon isotope fractionation processes induced by CO2 photolysis and 13C-involved chemical reactions in the early Martian photochemistry model13,15, based on PROTEUS (Photochemical and RaiatiOn Transport model for Extensive USe)40. This model calculates the time-dependent density profile of each species by solving the vertical transport and the continuity equations along with chemical reactions. We consider 82 chemical reactions (see Supplementary Information) for 18 species: 12CO2, 12CO, O, O(1D), H2O, H, OH, H2, O3, O2, HO2, H2O2, H212CO, H12CO, 13CO2, 13CO, H213CO, and H13CO. We use a 13CO2 absorption cross-section that Schmidt et al.10 theoretically calculated, as implemented in Yoshida et al.13. Absorption cross-sections of all other species are described in Nakamura et al.40. The reaction rate coefficients of the reactions, including H13CO and H213CO, are assumed to be the same as H12CO and H212CO. Eddy diffusion coefficient is assumed to be the same as Koyama et al.15.

We assume the escapes of H, H2, C, and O for the upper boundary conditions. H and H2 escape at the diffusion-limited velocity41. C and O escape by the non-thermal escape flux estimated under different solar EUV conditions by Amerstorfer et al.42 (see Supplementary Information for details). C escape is implemented by CO escape with the same amount of O return flux in the model. The carbon escape fractionation factor (fesc) is assumed to be 0.6 for the nominal condition24. This value represents the effect of CO photodissociation, but it could be varied by other mechanisms. For example, it could lower to ~ 0.4 if the gravitational fractionation effect is included13. It ranges up to ~ 0.8 depending on the escape mechanisms of carbon43. This uncertainty is evaluated in the error in the results (Fig. 1). The sensitivity of the fractionation factor is discussed in Supplementary Information.

As for the lower boundary condition, H2 is estimated to be degassed at a rate of 2 × 1011 cm−2 s−1, given that the oxygen fugacity of the Martian upper mantle was more reduced than Earth’s, with oxygen fugacity around the IW (iron-wüstite) buffer44,45. We consider both CO2 and CO volcanic degassing as a nominal condition. We adopt the evolution of the total carbon outgassing rate taken from Kurokawa et al.25 based on the geologic records of volcanism on Mars46, as shown in Supplementary Information. The ratio of CO/CO2 outgassing rate is estimated assuming a chemical equilibrium at the IW buffer (see Supplementary Information for details). Deposition velocities are applied to H212CO and H213CO at 0.1 cm s−1 and to H12CO and H13CO at 1 cm s−134,47. Deposition velocities for other species are listed in Supplementary Information. The rainout of H2CO and H213CO is included by using the same parameterization as Hu et al.48. The reduction factor is taken to be 0.1 because the 3-D global circulation model27 suggested that globally averaged precipitation on early Mars may have been 10 times smaller than that on Earth.

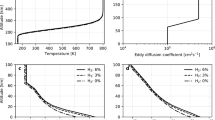

Climate model

We use a line-by-line radiative-convective model developed by Wordsworth et al.49 to calculate temperature profiles under different surface pressures and atmospheric compositions through the atmospheric evolution of Mars. For longwave radiative transfer calculations with the wavenumber from 1 to 2500 cm−1, we newly consider line absorption by CO in addition to line absorption by H2O and CO2, H2O continuum absorption, and collision-induced absorption by CO2-CO2, CO2-H2, H2O-H2O, and H2-H2 pairs, but CO has little effect on surface temperature due to the weak absorption intensity at infrared wavelength range50. The planetary albedo is assumed to be 0.2 referring to the present-day Martian value as the standard case. The effects of a change in the planetary albedo are discussed in Results and discussion section. Using this climate model, we create a lookup table of temperature profiles as a function of surface pressures and mixing ratios of CO2, CO, and H2. The surface pressure is presented in increments of 0.1 bar, ranging from 0.5 to 2 bar, and the mixing ratios are established in 10% increments for CO2 and CO, and in 1% increments for H2. The temperature profile in the troposphere is taken from this climate model, and that above the tropopause is assumed to be constant at the skin temperature of 167 K41. The temperature profiles of 1 bar CO2 and CO atmosphere with 1% H2 are shown in Supplementary Information as an example.

Coupled photochemistry-climate evolution model

Using the photochemistry and the created lookup table of the temperature profile, we calculate the time evolution of the Martian atmospheric composition while updating the temperature profile. We assume the volcanically or impact-degassed CO2 and CO atmosphere containing H2 gas as an initial condition. This corresponds to the scenario where the initial CO atmosphere is produced from impacts, volcanism, or oxidation of mantle-derived CH4 after the strong carbon escape driven by EUV flux21, and some fractions of CO are oxidized to CO2. For the nominal case, the initial atmospheres of 1 and 2 bars are assumed to be composed of 30% CO2, 69% CO, and 1% H2. We employ a δ13C of − 25 ± 5‰ in the initial CO2 and CO atmosphere based on the analysis of SNC (shergottite-nakhlite-chassignite) meteorites28. This uncertainty of ± 5‰ is evaluated in the error bar in the results (Fig. 1). The starting time is chosen at 4 Ga for the nominal case. These initial atmospheric composition and age are not constrained. Therefore, our calculated results could be shifted by several million years in time, but the evolutional trend remains the same (see Supplementary Information). Beginning from the initial atmosphere, we run the photochemical calculation for 800 Myr while updating the temperature profile and time-dependent boundary conditions of escape and volcanic outgassing every 100 Myr.

Data availability

The data of the simulation results is available at figshare repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25757424.

References

Eigenbrode, J. L. et al. Organic matter preserved in 3 billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater Mars. Science 360, 1096–1101 (2018).

House, C. H. et al. Depleted carbon isotope compositions observed at Gale crater Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2115651119 (2022).

Steele, A. et al. Organic synthesis on Mars by electrochemical reduction of CO2. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5118 (2018).

Franz, H. B. et al. Indigenous and exogenous organics and surface–atmosphere cycling inferred from carbon and oxygen isotopes at Gale crater. Nat. Astron. 4, 526–532 (2020).

Steele, A., McCubbin, F. M. & Fries, M. D. The provenance, formation, and implications of reduced carbon phases in Martian meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 51, 2203–2225 (2016).

Steele, A. et al. Organic synthesis associated with serpentinization and carbonation on early Mars. Science 375, 172–177 (2022).

Alexander, C. M. O., Fogel, M., Yabuta, H. & Cody, G. D. The origin and evolution of chondrites recorded in the elemental and isotopic compositions of their macromolecular organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4380–4403 (2007).

Chyba, C. & Sagan, C. Endogenous production, exogenous delivery and impact-shock synthesis of organic molecules: An inventory for the origins of life. Nature 355, 125–132 (1992).

Ueno, Y. et al. Synthesis of 13C-depleted organic matter from CO in a reducing early Martian atmosphere. Nat. Geosci. 17, 503–507 (2024).

Schmidt, J. A., Johnson, M. S. & Schinke, R. Carbon dioxide photolysis from 150 to 210 nm: Singlet and triplet channel dynamics, UV-spectrum, and isotope effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 17691–17696 (2013).

Aoki, S. et al. Depletion of 13C in CO in the atmosphere of Mars suggested by ExoMars-TGO/NOMAD observations. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 97 (2023).

Alday, J. et al. Photochemical depletion of heavy CO isotopes in the Martian atmosphere. Nat. Astron. 7, 867–876 (2023).

Yoshida, T. et al. Strong depletion of 13C in CO induced by photolysis of CO2 in the Martian atmosphere, calculated by a photochemical model. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 53 (2023).

Beale, C. A., Buzan, E. M., Boone, C. D. & Bernath, P. F. Near-global distribution of CO isotopic fractionation in the Earth’s atmosphere. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 323, 59–66 (2016).

Koyama, S. et al. Atmospheric formaldehyde production on early Mars leading to a potential formation of bio-important molecules. Sci. Rep. 14, 2397 (2024).

Furukawa, Y. et al. Extraterrestrial ribose and other sugars in primitive meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 24440–24445 (2019).

Furukawa, Y., Iwasa, Y. & Chikaraishi, Y. Synthesis of 13C-enriched amino acids with 13C-depleted insoluble organic matter in a formose-type reaction in the early solar system. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd3575 (2021).

Ono, C. et al. Abiotic ribose synthesis under aqueous environments with various chemical conditions. Astrobiology 24, 489–497 (2024).

Schaefer, L. & Fegley, B. Jr. Chemistry of atmospheres formed during accretion of the Earth and other terrestrial planets. Icarus 208, 438–448 (2010).

Saito, H. & Kuramoto, K. Formation of a hybrid-type proto-atmosphere on Mars accreting in the solar nebula. Mon. Not. Royal Astron. Soc. 475, 1274–1287 (2018).

Tian, F., Kasting, J. F. & Solomon, S. C. Thermal escape of carbon from the early Martian atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L02205 (2009).

Yoshida, T. & Kuramoto, K. Sluggish hydrodynamic escape of early martian atmosphere with reduced chemical compositions. Icarus 345, 113740 (2020).

Kite, E. S., Williams, J.-P., Lucas, A. & Aharonson, O. Low palaeopressure of the martian atmosphere estimated from the size distribution of ancient craters. Nat. Geosci. 7, 335–339 (2014).

Hu, R., Kass, D. M., Ehlmann, B. L. & Yung, Y. L. Tracing the fate of carbon and the atmospheric evolution of Mars. Nat. Commun. 6, 10003 (2015).

Kurokawa, H., Kurosawa, K. & Usui, T. A lower limit of atmospheric pressure on early Mars inferred from nitrogen and argon isotopic compositions. Icarus 299, 443–459 (2018).

Wordsworth, R. D. The climate of early Mars. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 381–408 (2016).

Kamada, A., Kuroda, T., Kasaba, Y., Terada, N. & Nakagawa, H. Global climate and river transport simulations of early Mars around the Noachian and Hesperian boundary. Icarus 368, 114618 (2021).

Wright, I. P., Grady, M. M. & Pillinger, C. T. Chassigny and the nakhlites: Carbon-bearing components and their relationship to martian environmental conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 817–826 (1992).

Borg, L. E. et al. The age of the carbonates in martian meteorite ALH84001. Science 286, 90–94 (1999).

Kopparapu, R. K. et al. Habitable zones around main-sequence stars: New estimates. Astrophys. J. 765, 131 (2013).

Zahnle, K., Haberle, R. M., Catling, D. C. & Kasting, J. F. Photochemical instability of the ancient Martian atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 113, E11 (2008).

Koyama, S., Terada, N., Nakagawa, H., Kuroda, T. & Sekine, Y. Stability of atmospheric redox states of early Mars inferred from time response of the regulation of H and O losses. Astrophys. J. 912, 135 (2021).

Wordsworth, R. et al. Transient reducing greenhouse warming on early Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 665–671 (2017).

Batalha, N., Domagal-Goldman, S. D., Ramirez, R. & Kasting, J. F. Testing the early Mars H2–CO2 greenhouse hypothesis with a 1-D photochemical model. Icarus 258, 337–349 (2015).

Chyba, C. F. Terrestrial mantle siderophiles and the lunar impact record. Icarus 92, 217–233 (1991).

Meller, R. & Moortgat, G. K. Temperature dependence of the absorption cross sections of formaldehyde between 223 and 323 K in the wavelength range 225–375 nm. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 7089–7101 (2000).

Cody, G. D. et al. Establishing a molecular relationship between chondritic and cometary organic solids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 19171–19176 (2011).

Kuramoto, K. et al. Martian moons exploration MMX: Sample return mission to phobos elucidating formation processes of habitable planets. Earth Planets Space 74, 12 (2022).

Hyodo, R., Kurosawa, K., Genda, H., Usui, T. & Fujita, K. Transport of impact ejecta from Mars to its moons as a means to reveal Martian history. Sci. Rep. 9, 19833 (2019).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Photochemical and radiation transport model for extensive use (PROTEUS). Earth Planets Space 75, 140 (2023).

Catling, D. C. & Kasting, J. F. Atmospheric Evolution on Inhabited and Lifeless Worlds (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Amerstorfer, U. V. et al. Escape and evolution of Mars’s CO2 atmosphere: Influence of suprathermal atoms. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 122, 1321–1337 (2017).

Thomas, T. B., Hu, R. & Lo, D. Y. Constraints on the size and composition of the ancient Martian atmosphere from coupled CO2–N2–Ar isotopic evolution models. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 41 (2023).

Grott, M., Morschhauser, A., Breuer, D. & Hauber, E. Volcanic outgassing of CO2 and H2O on Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 308, 391–400 (2011).

Cartier, C. et al. Experimental study of trace element partitioning between enstatite and melt in enstatite chondrites at low oxygen fugacities and 5 GPa. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 130, 167–187 (2014).

Craddock, R. A. & Greeley, R. Minimum estimates of the amount and timing of gases released into the martian atmosphere from volcanic eruptions. Icarus 204, 512–526 (2009).

Pearce, B. K. D., Molaverdikhani, K., Pudritz, R. E., Henning, T. & Cerrillo, K. E. Toward RNA life on early Earth: From atmospheric HCN to biomolecule production in warm little ponds. Astrophys. J. 932, 9 (2022).

Hu, R., Seager, S. & Bains, W. Photochemistry in terrestrial exoplanet atmospheres. I. Photochemistry model and benchmark cases. Astrophys. J. 761, 166 (2012).

Wordsworth, R. et al. A coupled model of episodic warming, oxidation and geochemical transitions on early Mars. Nat. Geosci. 14, 127–132 (2021).

Gordon, I. E. et al. The HITRAN2016 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 203, 3–69 (2017).

Stern, J. C. et al. Organic carbon concentrations in 3.5 billion-year-old lacustrine mudstones of Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2201139119 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the International Joint Graduate Program in Earth and Environmental Sciences, Tohoku University (GP-EES), and JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers: JP22KJ0314 to S.K; JP24KJ0066 to Y.N.; JP22H05149 and JP22H05151 to Y.U; JP23K13166 to A.K.; JP22H00164 to N.T.

Funding

International Joint Graduate Program in Earth and Environmental Sciences, Tohoku University (GP-EES), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, JP22KJ0314, JP22H00164, JP22H05149, JP24KJ0066, JP23K13166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K., T.Y., and N.T. designed the study. S.K. performed all the model calculations. S.K., Y.N., and T.Y. developed the photochemistry model, and S.K. developed the coupled photochemistry-climate evolution model. S.K. took the lead in writing the manuscript. Y.F. and Y.U. contributed to the interpretation of the origin of early Martian organic matter. All authors interpreted the results and improved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koyama, S., Yoshida, T., Furukawa, Y. et al. Stable carbon isotope evolution of formaldehyde on early Mars. Sci Rep 14, 21214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71301-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71301-w

This article is cited by

-

Carbonate formation and fluctuating habitability on Mars

Nature (2025)