Abstract

Freshwater ecosystems are crucial for global biodiversity through supporting plant and animal species and providing essential resources. These ecosystems are under significant threat, particularly in island environments such as Madagascar. Our study focuses on the Amboaboa River basin, home to the rare and endemic fish species Rheocles derhami, last recorded in 2013. To assess the status of this and other threatened fish species including Ptychochromis insolitus and Paretroplus gymnopreopercularis, and to understand freshwater fish population dynamics in this biodiversity hotspot, we conducted a comprehensive survey using both environmental DNA (eDNA) and traditional fishing methods. While traditional methods effectively captured a diverse range of species, including several invasive aliens and the critically endangered endemic species that were the focus of this study, the eDNA approach detected only a fraction of these introduced species and struggled to identify some critically endangered endemics at the species level. This highlights the value of combining methods to enhance species detection. We also investigated the trade-offs associated with multi-primer assessments in eDNA analysis, focusing on three different primer combinations targeting the 12S mitochondrial gene: MiFish, Tele02, and Riaz. Additionally, we provided 12S reference barcodes for 10 species across 9 genera of fishes from the region to increase the coverage of the public reference databases. Overall, our study elucidates the current state of freshwater biodiversity in the Amboaboa River basin and underscores the value of employing multiple methods for effective conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Freshwater ecosystems worldwide play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of our planet's biodiversity1. These habitats encompass rivers, lakes, wetlands, and streams, and serve as vital sources of drinking water, irrigation, transportation, and energy production, as well as being biodiversity hotspots providing habitats for countless plant and animal species2,3. However, these ecosystems are now facing alarming threats, including riparian deforestation, over-extraction of water resources, climate change, and pollution from industrial, agricultural, and urban sources4,5. These human-induced pressures disrupt the balance within freshwater ecosystems, leading to habitat degradation, species extinctions, and compromised water quality6,7.

Freshwater ecosystems on islands are particularly threatened, and this is especially the case for Madagascar8. It is the fourth largest island in the world, separated from the African mainland around 88 million years ago, fostering unique ecosystems and a rich tapestry of biodiversity9. It boasts diverse climates, from tropical coastlines to arid southwest regions and temperate highlands10. With a human population of over 30 million, Madagascar struggles with high poverty rates, and many rely on agriculture for sustenance8,11. Madagascar is home to a unique and varied biodiversity but also faces escalating challenges10. Its terrestrial and marine ecosystems are critical conservation priorities due to their remarkable vertebrate and invertebrate biodiversity, characterized by high endemism, which plays a significant role in maintaining these ecosystems12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Regarding fish species, the focus of this study, 173 fish species were previously recorded from Malagasy freshwater habitats, where 123 exclusively inhabit freshwater; 79 of these are endemic to Madagascar, and 50 are classified as threatened13. Unfortunately, this unique biodiversity faces severe threats such as the extensive decline in forested areas, resulting in sedimentation of breeding grounds and modifications in water flow, purity, and nutrient influx19. In regions where hills have been cleared due to slash-and-burn farming, secondary vegetation is often inadequate in preventing soil erosion20, resulting in the continuous sedimentation of aquatic habitats. Moreover, invasive species have a strong impact in Madagascar waters, where many areas have had their native fishes displaced by exotic species19,21. As a result there is an urgent need for comprehensive conservation efforts to safeguard Madagascar's biodiversity and protect its remarkable ecosystems, ensuring that its endemic species continue to thrive for generations to come19.

The Sofia drainage, an extensive freshwater network in northeastern Madagascar, is renowned for its rich biodiversity and unique flora and fauna22. The region is home to a variety of endemic species, and plays a crucial role in maintaining the ecological balance of the area by providing essential water resources for both the local communities and the diverse ecosystems it encompasses19. Within this vast freshwater network, the Amboaboa River stands out as an important Key Biodiversity Area in Madagascar by being the last known watershed for three Critically Endangered species: the cichlids Ptychochromis insolitus Stiassny & Sparks, 2006 (considered extinct in the wild until rediscovery in 2013), Paretroplus gymnopreopercularis Sparks, 2008, and the Madagascan rainbowfish Rheocles derhami Stiassny & Rodriguez, 2001, making the catchment a critical habitat and priority for conservation efforts 13,19,21. In 2013, only one R. derhami specimen was caught during the traditional sampling expeditions along the river and no specimens have been recorded in the subsequent expeditions in 2014, 2016, 2017 and 2018 (Fusari pers. comm.). This species has no ex-situ population established within the trade industry or zoological institutions, which leaves it at high risk of extinction13. The combined effects of non-native species introductions, excessive fishing, and deforestation, have left the freshwater fish species from these areas in Madagascar amongst the most threatened among vertebrate taxa23.

Traditional sampling methods are facing challenges in accurately estimating the area of occupancy and confirming the presence of these Critically Endangered species in the river, due to the difficulties in accessing the Madagascar complex environments and its rich biodiversity24. Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has emerged as a transformative approach that can facilitate the assessment of biodiversity monitoring25. By harnessing the genetic material that living and dead organisms release into their environment through various biological processes, eDNA provides a non-invasive, minimally disruptive method for detecting and monitoring species presence26,27. This innovative method can detect rare, elusive, or cryptic species that may not be detected by conventional sampling techniques28. Additionally, it allows for large-scale sampling across diverse habitats simultaneously, enhancing both spatial coverage and efficiency29. With these advantages, eDNA-based monitoring is a powerful tool for improving biodiversity assessment, as it provides more accurate and sustainable insights into ecosystem health and species distributions, which are essential for the conservation of freshwater ecosystems25,30,31,32.

However, some considerations should be taken when using eDNA-based detection28,33. The selection of primers plays a crucial role in environmental DNA studies, as it can determine the sensitivity, specificity, and efficacy of species detection, as well as the reliable detection of low-abundance or rare species34,35,36,37,38. The use of several primer sets can give more robust information of the species present in the environment, especially in highly diverse areas, as each primer pair will yield different identifications subject to a variety of factors, including the availability of reference sequences enabling confident species-level identification, the ability to discriminate between closely-related species, and DNA amplification efficiency38,39,40,41,42,43,44. MiFish-U-F and MiFish-U-R45, referred later in the manuscript as MiFish primers, Tele02 Forward and Reverse46, referred later as Tele02 primers, and 12S-V5 Forward and Reverse47,48, referred later in the manuscript as Riaz primers, are distinct sets of primers targeting a short fragment (106–209 bp) of the 12S mitochondrial gene, commonly employed in eDNA-based detection of fish species. Each of these primer sets has been shown to have its own unique characteristics and applications40,49. Indeed, while MiFish primers were originally designed for targeting fish communities45, it's important to recognize that the sequences used for their development differ significantly from the fish species typically found in Madagascar, therefore, these primers may not be the most suitable option for this region. The Riaz primers, on the other hand, have a broader applicability as it was designed to target vertebrates in general, yet maintain a great performance in elucidating the composition of fish communities36,38. Tele02 primers, like MiFish, were designed to target fish communities and have been shown to recover a higher species richness compared to MiFish primers40.

In this study, we combined conventional fishing techniques and molecular-based detection methods, with a particular focus on environmental DNA, where we evaluated the efficacy of these two methods to accurately assess fish diversity in Amboaboa River basin. Furthermore, we explored the trade-offs associated with various primer sets used in eDNA analysis—MiFish, Tele02, and Riaz, to detect the rare and endemic fish species present in the area. Furthermore, as we also acknowledge the challenges posed by incomplete reference databases to species identification and to ensure the accuracy of our eDNA assessment, we also performed DNA references barcodes on fish caught through traditional fishing methods before analysing our eDNA samples.

Methods

Study sites

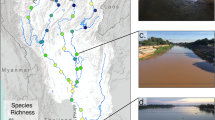

Traditional fishing and eDNA sampling were conducted along the Amboaboa River and the upper reaches of the Anjombony and Simianona Rivers, which are integral components of the Sofia drainage, located near the Marotandrano special reserve. This river system is located in the north-western part of the country and is rich in endemic fish species19. A comprehensive sampling effort was undertaken from the 13th to the 27th of November 2021, encompassing 14 distinct locations along 5 rivers (Anjombony, Manambendrana, Manampaneva, Amboaboa, and Vakoana) located in two different networks, Sofia and Ambodivato (Fig. 1). These locations were chosen based on pre-existing knowledge of historical observation of R. derhami, and site accessibility.

Location of sampling sites in the Sofia (Anjombony, Manambendrana, Manampaneva, Amboaboa) and Ambodivato (Vakoana) river drainages. The map was generated using QGIS v3.32.0 (https://www.qgis.org).

eDNA sampling

At 12 locations, three independent water samples were first collected in sterile plastic bags (Whirl–Pak 1650 ml) and filtered through 0.45 μm and 25 mm diameter cellulose acetate membranes (Whatman) placed inside 25 mm diameter Swinnex filter holders (Millipore) using 60 ml syringes (sterile luer-lock, BD Plastipak) (see Supplementary Table S1). At each site, the same filter holder was used to filter three natural replicates. In one additional location (Ambodivato), only one water sample was collected and filtered (see Supplementary Table S1). Sub-samples were collected regularly from surface water at each sampling location and pooled together to create representative independent water samples. This was done to decrease later stochasticity and variability of eDNA detection. The volume of water filtered for each sample ranged from 120 to 1000 ml and can be found in Supplementary Table S1 with other environmental variables collected at each site. Following water collection and filtration, each filter membrane holding the captured eDNA was removed from the Swinnex filter holder and placed into a 2 ml Eppendorf tube and preserved by adding 1.5 ml of absolute ethanol as a preservation buffer. Eppendorf tubes containing the filters were wrapped with parafilm and kept in the dark at room temperature until the end of fieldwork. Once in the laboratory, Eppendorf tubes containing the filters were stored at -20 °C until the extraction process. New sterile equipment and disposable gloves were used at each location during the sampling and filtration process to avoid cross-contamination between sites.

Traditional fishing

Traditional fishing was performed after eDNA collection in the 12 locations previously sampled for eDNA (i.e. water sampling and filtration), and in two additional other locations. This was done to avoid contamination between sites due to the fishing gears and water sampling following fishing activities. Traditional fishing was conducted using seine nets with a mesh aperture of 1 cm, cast nets, and mosquito nets. The sampling effort was only performed during the daytime period, and its duration was standardised to a 2-h interval to avoid variability due to site dependent condition and access. Following the fishing effort, fin clips were collected from a subset of the captured fish for later barcoding analysis and to confirm their visual identification.

DNA analysis

Fin clips were collected from Rheocles derhami (N = 9), Pachypanchax sp. Sofia (N = 13), Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852) (N = 1), Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) (N = 5), Gambusia holbrooki Girard, 1859 (N = 4), Paretroplus nourissati (Allgayer, 1998) (N = 9), Sauvagella robusta Stiassny, 2002 (N = 9), Ptychochromis insolitus (N = 3), Carassius auratus (Linnaeus, 1758) (N = 2), Rheocles sp. Ambodivato (N = 3), Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758 (N = 1), Awaous aeneofuscus (Peters, 1852) (N = 3). DNA from these tissue samples was extracted in a PCR free room using the Qiagen DNeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer's instructions and an approximately 600 bp fragment of the 12S region was amplified using the V05F_898 (5′-AAACTCGTGCCAGCCACC-3′) and TeleoR (5′-CTTCCGGTACACTTACCATG-3′)49,50. PCR products were then sent to Macrogen Europe B.V. for sequencing. DNA sequences were aligned and cleaned using the Geneious Pro R10 software (https://www.geneious.com),51 and species identification was confirmed using the Blast option from NCBI website 52(https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The resulting 12S DNA reference barcodes were later used for the taxonomic identification during the metabarcoding analysis of the eDNA samples. Genbank accession IDs for these 12S reference barcodes can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

eDNA metabarcoding analysis

A total of 34 unique eDNA samples were collected over 12 locations (see Supplementary Table S1). Extractions were completed in a PCR free room, and eDNA samples were extracted using the QIAGEN Blood and DNA Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications (i.e. ATL buffer, proteinase K, AL buffer and absolute ethanol amount were doubled to ensure an efficient extraction of the eDNA samples). No in-field controls or extraction blanks were used due to logistical challenges. Future studies should include both to ensure data integrity. DNA amplification of short specific regions of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA was conducted using the following metabarcoding primers: a 172 bp fragment using the MiFish‐U‐F 5′‐GCCGGTAAAACTCGTGCCAGC‐3′ and MiFish‐U‐R 5′‐CATAGTGGGGTATCTAATCCCAGTTTG‐3′ primers45,53; a 106 bp fragment using the 12S-V5F/R 5′-ACTGGGATTAGATACCCC-3′/5′-TAGAACAGGCTCCTCTAG-3′ primer pair47,48; and an approximately 167 bp fragment (from 129 to 209 bp) using the Tele02F/R 5′-AAACTCGTGCCAGCCACC-3′/5′-GGGTATCTAATCCCAGTTTG-3′ primer pair46 (Fig. 2). The selection of these primers was based on their applicability and resolution for assessing fish communities36,40,52.

PCR amplifications were conducted in triplicate, and negative controls (PCR blanks, i.e. samples where the template DNA was replaced with ddH2O at the PCR step) were included to ensure the accuracy of the results and absence of contamination. Amplicon libraries with MiFish, Riaz and Tele02 primers were conducted with indexed primers following Fadrosh et al.54. PCR conditions was: 10 μl of 2X Q5 hot start high fidelity mastermix (New England Biolabs Inc, UK), 1 μl of each indexed primer (2 μM each), 4 μL of nuclease free water and 4 μl of extracted eDNA in a final volume of 20 μL. PCR products were visualised on agarose gels and quantified using ImageLab Software v6.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA)55. To ensure equal representation of all amplicons, equimolar amounts, based on the gel image information, of each amplicon were merged using a Biomek4000 liquid handling robot (Beckman Coulter, USA). The DNA amplicon pool was then cleaned using 10 rxns of Illustra ExoStar, as well as a 1.0X AMpure bead clean (Beckman Coulter, USA) before performing size selection using BluePippin (Sage Science, USA) targeting the respective marker size. A final quality control was done by visualizing the pooled amplicons on a Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Inc., USA) using the High Sensitivity Genomic DNA Kit (Agilent) before the sample went through a ThruPLEX DNA-seq (Takara Bio USA, Inc) library preparation and sequencing on an Illumina Miseq platform using a 250 bp paired-end reads kit (Illumina Inc.) at the Norwegian Sequencing Centre. The raw sequencing data from the metabarcoding analysis are deposited in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8406716).

Bioinformatics and data analysis

Firstly, quality control of sequence data was checked using FastQC reports (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). The next steps conducted for the metabarcoding analysis (i.e. merging, demultiplexing and data cleaning steps) followed44,55, and only the denoising and the taxonomic assignment were different. In our datasets, the sequences were clustered at 97% similarity with USEARCH to form OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units;56). Subsequently, taxonomy was assigned at 90% similarity using the ‘vsearch -sintax’ function in VSEARCH software57 with a custom database where we added our barcoding sequences to the Midori2 database (srRNA; 58) (see Supplementary Table S3).

To remove false positives and possible contaminants or sequencing errors, we removed the maximum number of reads detected in the controls for each OTU from all samples44,59. Following this, the replicates from each locality were pulled together and the OTUs containing less than 10 reads overall were discarded. Species that were not the target of the study or OTUs likely originating from carry-over contaminations were eliminated from the dataset59,60. Statistical analyses and visualisation were made using RStudio (RStudio Team, 2020), and the package Phyloseq61. The relative read abundance (RRA) was obtained for each OTU, by dividing the number of OTUs copies by the sum of the number of copies of all OTUs in the sample, and then the plots for each marker were generated using ggplot262. The Venn diagram was produced using the online platform—http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/. To compare the relationship of fishing similarities among each primer set, Jaccard similarity was calculated and ordinated using non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS).

Results

Traditional fishing

Traditional fishing effort was conducted at 14 locations (see Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, we were not able to capture any fish in four locations “Manampaneva upstream”, “Ambohipaka”, “Ambarijeby” and “Ambodimanga maiky” despite local fishermen highlighting the presence of fish species at these locations. In the remaining 10 locations, we were able to capture Rheocles derhami (N = 331), Pachypanchax sp. Sofia (N = 44), Oreochromis mossambicus (N = 201), Oreochromis niloticus (N = 84), Gambusia holbrooki (N = 30), Paretroplus nourissati (N = 37), Sauvagella robusta (N = 127), Ptychochromis insolitus (N = 4), Carassius auratus (N = 9), Rheocles sp. Ambodivato (N = 7), Cyprinus carpio (N = 12), Awaous aeneofuscus (N = 4), Xiphophorus maculatus (Günther 1866) (N = 74), Awaous macrorhynchus (Bleeker, 1867) (N = 1) and Paretroplus gymnopreopercularis (N = 1). An overview of fish species captured and their abundance at each location can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Details regarding the number of individuals of each species selected for the barcoding at each location can be found in Supplementary Table S3. Despite Rheocles derhami remaining undetected in the Amboaboa river basin since the last record in 2013, we were able to find relatively high numbers of specimens of this species. Rheocles specimens were additionally found outside of their expected range, in the Ambodivato drainage. We refer to these individuals as Rheocles sp. Ambodivato due to potential uncertainty regarding taxonomic delimitation.

Barcoding results

DNA was successfully amplified and sequenced from Rheocles derhami (N = 6), Pachypanchax sp. Sofia (N = 2), Oreochromis niloticus (N = 6), Gambusia holbrooki (N = 3), Paretroplus nourissati (N = 9), Sauvagella robusta (N = 7), Ptychochromis insolitus (N = 3), Carassius auratus (N = 1), Rheocles sp. Ambodivato (N = 3), Awaous aeneofuscus (N = 2). DNA sequence accession numbers (OR737848 to OR737884) can be found in Supplementary Table S4. Notably, Rheocles from the Amboaboa and Ambodivato rivers exhibit substantial genetic and morphological distinctions, suggesting the possibility of two distinct species. For this reason, we included DNA sequences from these species in supplementary information. We did the same for the Pachypanchax sp. Sofia specimen. However, it is important to clarify that the formal description of these species falls beyond the scope of this current paper.

Metabarcoding

Following bioinformatic processing, a total of 1,879,986 reads remained from the 2 × 250 bp MiSeq run across the three primer sets, where 306,229 reads were assigned to the MiFish primer set, 669,245 reads to the Riaz set, and 904,512 reads to the Tele02 set. Following filtering, when only OTUs from fish were considered, the mean sequencing depth per PCR replicate was 1595 reads for MiFish, 1992 reads for Riaz, and 1675 reads for Tele02: an average of 1753 reads per sample across the three markers. The data of PCR replicates for each marker were combined (three PCR replicates per biological sample, and three biological samples per site, except for Ambodivato which had only one biological replicate) to give a mean sequencing depth of 1760 reads per site.

Comparison of eDNA and traditional fish surveys

At the 12 sites where eDNA and fishing sampling occurred, a total of 19 species were detected, with nine species detected by both methods: Oreochromis niloticus, Awaous aeneofuscus, Rheocles sp. Ambodivato, Oreochromis mossambicus, Cyprinus carpio, Pachypanchax sp. Sofia, Sauvagella robusta, Paretroplus nourissati, and Carassius auratus (Fig. 3). The fishing net approach exhibited enhanced discriminatory capability detecting exclusively six species, namely Gambusia holbrooki, Paretroplus gymnopreopercularis, Awaous macrorhynchus, Xiphophorus maculatus, Rheocles derhami, Ptychochromis insolitus (Fig. 3). In contrast, the eDNA approach yielded the capture of additional four species: Anguilla nebulosa McClelland, 1844, Netuma bilineata (Valenciennes, 1840), Anguilla mossambica (Peters, 1852), and Anguilla bicolor McClelland, 1844 (Fig. 3).

Comparison between the three 12S markers

The sequencing results of the three 12S markers successfully identified eight distinct fish families, 12 fish genera, and a total of 13 unique fish species. Pachypanchax sp. Sofia was the only species detected by the three markers (Fig. 3). MiFish and Riaz markers revealed the presence of Carassius auratus. MiFish and Tele02 markers identified the occurrence of Oreochromis niloticus and Anguilla mossambica, whereas Riaz exclusively recovered seven species: Oreochromis mossambicus, Cyprinus carpio, Rheocles sp. Ambodivato, Awaous aeneofuscus, Sauvagella robusta, Anguilla bicolor, and Paretroplus nourissati, MiFish marker detected Anguilla nebulosa, and Tele02 marker Netuma bilineata (Fig. 3) (see Supplementary Table S5). The three data sets also recovered sequences from other organisms, which were assigned to birds, mammals, invertebrates, bacteria, and fungi.

The rare and endemic Rheocles was detected at the genus level by MiFish and Tele02, and at species level as Rheocles sp. Ambodivato only by the Riaz primers (see Supplementary Table S5). Additionally, Riaz primers detected Ptychochromis, a genus of rare and endemic cichlids to Madagascar. The nMDS ordination of the fish assemblages revealed a similarity among the traditional sampling and the Riaz marker, and among MiFish and Tele02 (Fig. 4), which is consistent with the primers regions (Fig. 2). This variance in OTU retrieval highlights Riaz's heightened sensitivity in capturing taxonomic diversity. Tele02 facilitated the detection of other vertebrate species, as it also recovered the DNA of the vulnerable and endemic Eulemur fulvus (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1796) (IUCN, 2022), and MiFish detected two invasive species the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853 and the shrimp Macrobrachium nipponense (De Haan, 1849), further illustrating the potential of these markers to provide insights into the DNA of non-fish species inhabiting the same ecosystems (see Supplementary Table S6).

Relative abundance across sampling points

Observed relative OTU abundance showed that Oreochromis, Awaous and Pachypanchax were the most abundant genera through a larger portion of the sampling points in all three primer datasets (Fig. 5). Rheocles, Oreochromis and Sauvagella, were the most abundant in the Traditional sampling (see Supplementary Table S2). No fish reads were found in Ambavaranobe for the three markers, and for MiFish in the following four sites — Ambodibonara, Ampitamanatera, Ambohipaka, and Ambarijeby. Bekapika locality emerged as a hotspot for species richness, consistently exhibiting the highest species recovery across all three marker sets. Remarkably, Bekapika, Manapaneva barrage, and Manapaneva amount were the sites where the presence of the endemic Rheocles was detected, evidencing the significance of these specific locations in Amboaboa biodiversity assessment using the selected markers.

Discussion

In the understudied Amboaboa river basin in Madagascar, our dataset reveals a diverse range of fish species, both endemic and invasive, underscoring the ecological significance of this region. Our traditional sampling efforts captured invasive alien species, such as C. auratus, C. carpio, G. holbrooki, X. maculatus, O. niloticus, which can have detrimental impacts on native species through predation and resource competition by their high population densities19,23,63. This technique was particularly effective in detecting several critically endangered endemic species, including P. gymnopreopercularis, R. derhami, and P. insolitus13,19,63. The eDNA approach detected only a fraction of the introduced species compared to traditional methods (i.e. C. auratus, C. carpio, and O. niloticus), highlighting both the importance and limitations of this method in detecting the dramatic threat to native fishes in Madagascar12. The eDNA approach effectively detected the genus Rheocles across all three markers used and Rheocles sp. Ambodivato solely through Riaz markers. However, it failed to identify critically endangered species such as P. gymnopreopercularis, R. derhami, and P. insolitus at the species level13,19,63. Despite these limitations, other threatened groups were detected, including Sauvagella robusta, and various eels such as Anguilla nebulosa, A. bicolor, and the African longfinned eel A. mossambica, all of which are under pressure and require proactive conservation strategies64,65,66. Our study in the Amboaboa River basin demonstrates the value of combining traditional and eDNA survey methods for understanding and conserving aquatic biodiversity. These methods help detect a wide range of species, including rare and endangered ones, and highlight the challenges posed by invasive species. These findings emphasize the need for comprehensive conservation strategies to protect Madagascar’s unique aquatic ecosystems.

Another significant aspect of our study was the generation of several reference barcodes for the improvement of the reference database for the Amboaboa region. Our barcoding efforts resulted in a high coverage at genus and species level (Table S4), generating the most extensive 12S reference barcodes dataset for the region to date. Within our barcoding results, genetic differences were found in the genus Rheocles, suggesting that the species from the Amboaboa River (Sofia drainage, including the type locality of R. derhami) may be different from the Vakoana River (Ambodivato drainage), which corroborates with the loss of connectivity between these rivers, leading to a possible lack of genetic flow. A similar divergence was found between populations of Sauvagella robusta, where the specimens from Ambavaranobe presented different sequences from the Ankarahara and Antanilatsaka, suggesting the possibility of distinct species. However, the formal description of these species falls beyond the scope of the current paper, requiring revision of other material in these genera. While our results are promising, the effectiveness of the eDNA methodology could have been further improved with access to a more comprehensive reference sequence database for Malagasy fish. With better database resources, we could have identified more OTUs at the species level, potentially resulting in the detection of additional fish species. A crucial aspect in successfully matching OTUs generated through DNA metabarcoding is the availability of a reference database that contains identified specimens and their associated barcodes35,67,68. However, well-curated, regionally focused reference databases remain relatively scarce, especially in Madagascar. This hinders our ability to understand the spatio-temporal dynamics of species distributions39,68. Nonetheless, our barcoding efforts in the Sofia and Ambodivato drainages have increased the coverage at various taxonomic levels, including many new records at family, genus, and species levels. Nevertheless, more efforts should be made to improve the quality of the barcode dataset for the region.

The effectiveness of employing multiple genetic markers is being widely recognized as it minimizes the impact of biases that may be associated with any single method39,40,41,42,69,70,71,72. This multiple setting offers a way to address limitations related to specific gene regions, including binding amplification biases, incomplete databases, or the inability to distinguish closely related taxa42,70,73,74. In this study, three sets of 12S primers were employed, as these primers have demonstrated superior efficiency-based performance compared to other gene regions, being considered the current marker of choice for fish community assessments focused on eDNA analysis35,36,40,45,48,49,75. This combination detected not only aquatic vertebrates but also terrestrial vertebrates, including the vulnerable and endemic Common Brown Lemur (Eulemur fulvus), as well as invertebrates including the invasive shrimp Macrobrachium nipponense76, and the invasive Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) (see Supplementary Table S6), which may represent a new record of this species in Madagascar.

Despite the fact that the three datasets yielded similar outcomes, differences were observed in the performance of the primers. In our study within the Amboaboa river basin, we observed that the Riaz primers show a great potential to recover species richness when compared to the MiFish and Tele02 primers. Specifically, the results from Riaz presented more similarity with the traditional findings (Fig. 5), and assigned a greater number of OTUs to the fish species level, with nine OTUs identified, as opposed to five from MiFish and four from Tele02 primers. Additionally, the Riaz primer excelled in the detection of threatened groups, including the Rheocles, Sauvagella, and the rare cichlid genus Ptychochromis, and also detected the invasive taxa Cyprinus and Carassius, showing a better performance in characterizing the fish population in the area. When considering MiFish and Tele02, the smaller coverage, might be related to the initial portion of their fragment not being matched to the barcoding marker (Fig. 2), however, similar results were found between them, corroborating with their fragment overlap in the 12S gene region that targets bony fishes25,45,69. Neither of the primers achieved a full species-level resolution for the area, and this limitation could be attributed to either the absence of a comprehensive reference database or the design of these primers, which were originally based on different taxa than those found in Madagascar25,37,45,69. We acknowledge that including additional COI and 16S primers would have provided better resolution, given the comprehensive COI reference library available for Malagasy fishes and the broad taxonomic coverage of 16S12,77. Furthermore, an expanded barcoding effort would have been necessary to increase the likelihood of detecting a wider range of species, particularly those with limited genetic variation in the targeted regions78. Therefore, the selection of the most suitable primer sets for characterising fish communities depends on the particular objectives of conservation and research, and this choice should be made on a case-by-case basis. Notwithstanding, the use of several primer sets can give more robust information about the species present in the environment, as was seen in this study, the use of three markers for the 12S region offered together a better resolution for the Amboaboa river basin. The use of multiple primer pairs in combination, whenever possible, it is recommended as it has been shown to enhance species detection probability, rather than focusing on creating unique primer pairs, future efforts should prioritise the optimization of primer combinations that can maximise the potential for detecting species using eDNA38,39,40,41,42,69,79.

Finally, our work demonstrates the potential of enhancing aquatic biodiversity surveys by combining eDNA metabarcoding with traditional sampling methods, thereby expanding species coverage in understudied regions, such as Madagascar. With these combined methodologies, we were able to detect the endemic families Bedotiidae and Aplocheilidae, and the most diverse Malagasy freshwater fish family Cichlidae (Fig. 5)13. Our effort was successful in recording R. derhami, a Critically Endangered species, which only one specimen was caught in 2013 and none caught during traditional surveys in 2014, 2016, 2017 and 2018 (Fusari pers. comm.), nonetheless, it was again collected in larger numbers in this study, mainly at Ambodibonara, Ambavaranobe and Ampitamanatera rivers. Furthermore, two other Critically Endangered species were recorded. The cichlids P. insolitus (considered extinct in the wild until rediscovery in 2013), and P. gymnopreopercularis, were collected and/or detected with eDNA, making the Amboaboa River a critical habitat and priority for conservation and management initiatives13,19,21,23. Unfortunately several alien species were also found in the region, including the unexpected Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis, highlighting the potential of eDNA for early warning of the presence of this species in Madagascar, which is already invasive in many other regions80, however, a confirmation with capture of a specimen is needed to confirm this new record.

Data availability

Raw sequencing data from the metabarcoding analysis data can be found here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8406716. Sampling location and metadata can be found in supplementary information.

References

Arya, S. Freshwater biodiversity and conservation challenges: A review. IJBI 03, 75–78 (2021).

Borgwardt, F. et al. Exploring variability in environmental impact risk from human activities across aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 652, 1396–1408 (2019).

Water U. N. Water and Climate Change (UNESCO, 2020).

Prakash, S. Impact of climate change on aquatic ecosystem and its biodiversity: An overview. IJBI https://doi.org/10.46505/IJBI.2021.3210 (2021).

Elisha, O. D. & Felix, M. J. The loss of biodiversity and ecosystems: A threat to the functioning of our planet, economy and human society (2020).

Darwall, W. et al. The Alliance for Freshwater Life : A global call to unite efforts for freshwater biodiversity science and conservation. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 28, 1015–1022 (2018).

Scherer, L., Boom, H. A., Barbarossa, V. & Van Bodegom, P. M. Climate change threats to the global functional diversity of freshwater fish. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3781–3793 (2023).

Tiandraza, F. et al. Response of ecosystem services to land use change in Madagascar Island, Africa: A multi-scale perspective. IJERPH 20, 3060 (2023).

Wright, P. C. Lemur traits and Madagascar ecology: Coping with an island environment. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 110, 31–72 (1999).

Antonelli, A. et al. Madagascar’s extraordinary biodiversity: Evolution, distribution, and use. Science 378, eabf0869 (2022).

Neudert, R., Goetter, J. F., Andriamparany, J. N. & Rakotoarisoa, M. Income diversification, wealth, education and well-being in rural south-western Madagascar: Results from the Mahafaly region. Dev. South. Afr. 32, 758–784 (2015).

Vences, M., Stützer, D., Rasoamampionona Raminosoa, N. & Ziegler, T. Towards a DNA barcode library for Madagascar’s threatened ichthyofauna. PLoS ONE 17, e0271400 (2022).

Leiss, L. et al. Review of threatened Malagasy freshwater fishes in zoos and aquaria: The necessity of an ex situ conservation network—A call for action. Zoo Biol. 41, 244–262 (2022).

Eppley, T. M. et al. A habitat stronghold on the precipice: A call-to-action for supporting lemur conservation in northeast Madagascar. Am. J. Primatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23483 (2023).

Otero Jimenez, B., Montaño, R., Rothman, R. S., Williams, R. C. & Wright, P. C. A surprising haven: The biodiversity of an old-growth forest amidst a scorched landscape in Madagascar. Conserv. Sci. Prac. 5, e12993 (2023).

Goodman, S. M. Updated estimates of biotic diversity and endemism for Madagascar—revisited after 20 years. Oryx 57, 561–565 (2023).

Goodman, S. M. The new natural history of Madagascar (Princeton University Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691229409.

Vences, M., Wollenberg, K. C., Vieites, D. R. & Lees, D. C. Madagascar as a model region of species diversification. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 456–465 (2009).

Máiz-Tomé, L., Sayer, C. & Darwall, W. R. T. The status and distribution of freshwater biodiversity in Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands Hotspot. (IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2018). https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2018.RA.1.en.

Styger, E., Rakotondramasy, H. M., Pfeffer, M. J., Fernandes, E. C. M. & Bates, D. M. Influence of slash-and-burn farming practices on fallow succession and land degradation in the rainforest region of Madagascar. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 119, 257–269 (2007).

Sparks, J. S. Phylogeny of the cichlid subfamily etroplinae and taxonomic revision of the Malagasy Cichlid Genus Paretroplus (Teleostei: Cichlidae). Bull. Mus. Nat. Hist. 314, 1 (2008).

Wilmé, L. et al. Toponyms for centers of endemism in Madagascar. MCD 7, 30–40 (2012).

Benstead, J. P. et al. Conserving Madagascar’s freshwater biodiversity. BioScience 53, 1101 (2003).

Ralimanana, H. et al. Madagascar’s extraordinary biodiversity: Threats and opportunities. Science 378, eadf1466 (2022).

Taberlet, P., Bonin, A., Zinger, L. & Coissac, E. Environmental DNA: For biodiversity research and monitoring (Oxford University Press, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767220.001.0001.

Ruppert, K. M., Kline, R. J. & Rahman, M. S. Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: A systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA. Global Ecol. Conserv. 17, e00547 (2019).

Lynggaard, C. et al. Airborne environmental DNA for terrestrial vertebrate community monitoring. Curr. Biol. 32, 701-707.e5 (2022).

Beng, K. C. & Corlett, R. T. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in ecology and conservation: Opportunities, challenges and prospects. Biodivers. Conserv. 29, 2089–2121 (2020).

Carraro, L., Mächler, E., Wüthrich, R. & Altermatt, F. Environmental DNA allows upscaling spatial patterns of biodiversity in freshwater ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 11, 3585 (2020).

Pawlowski, J., Apothéloz-Perret-Gentil, L. & Altermatt, F. Environmental DNA: What’s behind the term? Clarifying the terminology and recommendations for its future use in biomonitoring. Mol. Ecol. 29, 4258–4264 (2020).

Pawlowski, J., Bonin, A., Boyer, F., Cordier, T. & Taberlet, P. Environmental DNA for biomonitoring. Mol. Ecol. 30, 2931–2936 (2021).

Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N. et al. Biodiversity monitoring using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 1405–1409 (2021).

Nagler, M., Podmirseg, S. M., Ascher-Jenull, J., Sint, D. & Traugott, M. Why eDNA fractions need consideration in biomonitoring. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 2458–2470 (2022).

Hajibabaei, M., Porter, T. M., Wright, M. & Rudar, J. COI metabarcoding primer choice affects richness and recovery of indicator taxa in freshwater systems. PLoS ONE 14, e0220953 (2019).

Schenekar, T., Schletterer, M., Lecaudey, L. A. & Weiss, S. J. Reference databases, primer choice, and assay sensitivity for environmental metabarcoding: Lessons learnt from a re-evaluation of an eDNA fish assessment in the Volga headwaters. River Res. Apps 36, 1004–1013 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Unrecognized contributions of dissolved organic matter inducing photodamages to the decay of extracellular DNA in waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1614–1622 (2020).

Macher, T.-H., Schütz, R., Yildiz, A., Beermann, A. & Leese, F. Evaluating Five Primer Pairs for Environmental DNA Metabarcoding of Central European Fish Species Based on Mock Communities. https://preprints.arphahub.com/article/104185/ (2023). https://doi.org/10.3897/arphapreprints.e104185.

Burian, A. et al. Merging two eDNA metabarcoding approaches and citizen-science-based sampling to facilitate fish community monitoring along vast Sub-Saharan coastlines. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 1641–1655 (2023).

Jerde, C. L., Wilson, E. A. & Dressler, T. L. Measuring global fish species richness with eDNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 19, 19–22 (2019).

Polanco, A. et al. Comparing the performance of 12S mitochondrial primers for fish environmental DNA across ecosystems. Environ. DNA 3, 1113–1127 (2021).

Blackman, R. C. et al. Mapping biodiversity hotspots of fish communities in subtropical streams through environmental DNA. Sci Rep 11, 10375 (2021).

Takahashi, M. et al. Aquatic environmental DNA: A review of the macro-organismal biomonitoring revolution. Sci. Total Environ. 873, 162322 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Methodology of fish eDNA and its applications in ecology and environment. Sci. Tot. Environ. 755, 142622 (2021).

Carvalho, C. O. et al. Harnessing eDNA metabarcoding to investigate fish community composition and its seasonal changes in the Oslo fjord. Sci. Rep. 14, 10154 (2024).

Miya, M. et al. MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2, 150088 (2015).

Wei, X.-Y. et al. Ultra-sensitive detection of ecologically rare fish from eDNA samples based on the RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a technology. iScience 26, 107519 (2023).

Riaz, T. et al. ecoPrimers: Inference of new DNA barcode markers from whole genome sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e145–e145 (2011).

Kelly, R. P., Port, J. A., Yamahara, K. M. & Crowder, L. B. Using environmental DNA to census marine fishes in a large Mesocosm. PLoS ONE 9, e86175 (2014).

Milan, D. T. et al. New 12S metabarcoding primers for enhanced Neotropical freshwater fish biodiversity assessment. Sci Rep 10, 17966 (2020).

Thomsen, P. F. et al. Environmental DNA from seawater samples correlate with Trawl catches of subarctic, deepwater fishes. PLoS ONE 11, e0165252 (2016).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012).

Valentini, A. et al. Next-generation monitoring of aquatic biodiversity using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. 25, 929–942 (2016).

Sales, N. G., Wangensteen, O. S., Carvalho, D. C. & Mariani, S. Influence of preservation methods, sample medium and sampling time on eDNA recovery in a neotropical river. Environ. DNA 1, 14 (2019).

Fadrosh, D. W. et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2, 6 (2014).

Raclariu-Manolică, A. C., Mauvisseau, Q., Paranaiba, R., De Boer, H. J. & Socaciu, C. Authentication of milk thistle commercial products using UHPLC-QTOF-ESI + MS metabolomics and DNA metabarcoding. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 23, 257 (2023).

Edgar, R. C. UNOISE2: Improved Error-Correction for Illumina 16S and ITS Amplicon Sequencing. (2016) https://doi.org/10.1101/081257.

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Leray, M., Knowlton, N. & Machida, R. J. MIDORI2: A collection of quality controlled, preformatted, and regularly updated reference databases for taxonomic assignment of eukaryotic mitochondrial sequences. Environ. DNA 4, 894–907 (2022).

Ribas, T. F. A. et al. Unexpected diversity in the diet of Doryteuthis sanpaulensis (Brakoniecki, 1984) (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) from the southern Brazilian sardine fishery identified by metabarcoding. Fish. Res. 239, 105936 (2021).

Li, J., Lawson Handley, L., Read, D. S. & Hänfling, B. The effect of filtration method on the efficiency of environmental DNA capture and quantification via metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 1102–1114 (2018).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. WIREs Comput. Stats 3, 180–185 (2011).

Fricke, R., Mahafina, J., Behivoke, F., Jaonalison, H. & Léopold, M. Annotated checklist of the fishes of Madagascar, southwestern Indian Ocean, with 158 new records. (2018).

Jacoby, D. M. P. et al. Synergistic patterns of threat and the challenges facing global anguillid eel conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 4, 321–333 (2015).

Frankowski, J., Lübke, K., Coke, M. & Weyl, O. L. F. Genetic variability and demographic history of Anguilla mossambica (Peters, 1852) from continental Africa and Madagascar. J. Fish Biol. 96, 1251–1259 (2020).

Hanzen, C. C. et al. Slippery customers for conservation: Distribution and decline of anguillid eels in South Africa. Aquat. Conserv. 32, 1277–1290 (2022).

Cilleros, K. et al. Unlocking biodiversity and conservation studies in high-diversity environments using environmental DNA (eDNA): A test with Guianese freshwater fishes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 19, 27–46 (2019).

Gaither, M. R., DiBattista, J. D., Leray, M. & Von Der Heyden, S. Metabarcoding the marine environment: From single species to biogeographic patterns. Environ. DNA 4, 3–8 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. VertU: Universal multilocus primer sets for eDNA metabarcoding of vertebrate diversity, evaluated by both artificial and natural cases. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1164206 (2023).

Morey, K. C., Bartley, T. J. & Hanner, R. H. Validating environmental DNA metabarcoding for marine fishes in diverse ecosystems using a public aquarium. Environ. DNA 2, 330–342 (2020).

Loeza-Quintana, T., Abbott, C. L., Heath, D. D., Bernatchez, L. & Hanner, R. H. Pathway to increase standards and competency of eDNA Surveys (PISCeS)—Advancing collaboration and standardization efforts in the field of eDNA. Environ. DNA 2, 255–260 (2020).

Shu, L., Ludwig, A. & Peng, Z. Standards for methods utilizing environmental DNA for detection of fish species. Genes 11, 296 (2020).

Lecaudey, L. A., Schletterer, M., Kuzovlev, V. V., Hahn, C. & Weiss, S. J. Fish diversity assessment in the headwaters of the Volga River using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Aquat. Conserv. 29, 1785–1800 (2019).

Doble, C. J. et al. Testing the performance of environmental DNA metabarcoding for surveying highly diverse tropical fish communities: A case study from Lake Tanganyika. Environ. DNA 2, 24–41 (2020).

Collins, R. A. et al. Non-specific amplification compromises environmental DNA metabarcoding with COI. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 1985–2001 (2019).

Hanamura, Y., Koizumi, N., Morioka, S., Andriantsoa, M. & Rafalimanana, T. Occurrence of the non-indigenous freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae) in Madagascar. Crustac 81, 1143–1149 (2008).

Vences, M. et al. Freshwater vertebrate metabarcoding on Illumina platforms using double-indexed primers of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 8, 323–327 (2016).

Phillips, J. D., Gillis, D. J. & Hanner, R. H. Incomplete estimates of genetic diversity within species: Implications for DNA barcoding. Ecol. Evol. 9, 2996–3010 (2019).

Evans, N. T. et al. Quantification of mesocosm fish and amphibian species diversity via environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 29–41 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Ensemble forecasting of the global potential distribution of the invasive Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Hydrobiologia 826, 367–377 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jarl Andreas Anmarkrud and Birgitte Lisbeth Graae Thorbek from the DNA lab at the Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo for their support and assistance in the lab. We also thank Clément Rafidimanana and Félix Randriamijery from Madagascar National Parks who guided the team in the field during the data collection trip.

Funding

QM and CEF acknowledge both the European Union of Aquarium Curators and the Union des Conservateurs d’Aquariums for providing funding for fieldwork and molecular analysis of the DNA and eDNA samples. QM acknowledges support from the Natural History Museum from the University of Oslo. Scientific research and sampling were conducted under the research permit 97/21-MPEB/SG/DGPA from the Ministère de la Pêche et de l’Economie Bleue, Secretariat General and Direction Générale de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture. DNA and eDNA samples were exported for analysis under the permit 055/22-MPEB/ASH from the Ministère de la Pêche et de l’Economie Bleue and Autorité Sanitaire Halieutique.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sampling: TR and FA, Molecular analysis: MP and AS-N, Data curation: COC and QM, Bioinformatics: COC and QM, Statistical analysis: COC and QM, Original draft: COC and QM, Review and editing: COC, MP, TR, FA, AS-N, JSR, HdB, C-EF, QM, Funding acquisition: C-EF and QM, Supervision: QM, JSR, HdB.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira Carvalho, C., Pazirgiannidi, M., Ravelomanana, T. et al. Multi-method survey rediscovers critically endangered species and strengthens Madagascar's freshwater fish conservation. Sci Rep 14, 20427 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71398-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71398-z

This article is cited by

-

Cost-effective eDNA methods for monitoring wild crocodiles

Biodiversity and Conservation (2025)