Abstract

Partial accelerated life tests (PALTs) are employed when the results of accelerated life testing cannot be extended to usage circumstances. This work discusses the challenge of different estimating strategies in constant PALT with complete data. The lifetime distribution of the test item is assumed to follow the power half-logistic distribution. Several classical and Bayesian estimation techniques are presented to estimate the distribution parameters and the acceleration factor of the power half-logistic distribution. These techniques include Anderson–Darling, maximum likelihood, Cramér von-Mises, ordinary least squares, weighted least squares, maximum product of spacing and Bayesian. Additionally, the Bayesian credible intervals and approximate confidence intervals are constructed. A simulation study is provided to compare the outcomes of various estimation methods that have been provided based on mean squared error, absolute average bias, length of intervals, and coverage probabilities. This study shows that the maximum product of spacing estimation is the most effective strategy among the options in most circumstances when adopting the minimum values for MSE and average bias. In the majority of situations, Bayesian method outperforms other methods when taking into account both MSE and average bias values. When comparing approximation confidence intervals to Bayesian credible intervals, the latter have a higher coverage probability and smaller average length. Two authentic data sets are examined for illustrative purposes. Examining the two real data sets shows that the value methods are workable and applicable to certain engineering-related problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today's highly competitive environment demands that manufacturers offer goods with improved reliability at lower costs and faster processing times. Accelerated life tests (ALTs) are therefore recommended for use in industrial sectors to quickly gather the appropriate amount of failure data to draw conclusions about the link between them and external stress factors. The test items in ALTs are only put to the test under expedited circumstances or stress levels that are greater than normal in order to cause early failures. To estimate the lifetime distribution under typical usage settings, data gathered under such accelerated conditions are then extrapolated using a statistical model that is appropriate for the physical environment. There are primarily three ALT techniques, according to Nelson1. The first approach, known as the constant-stress ALT, maintains a constant degree of stress for the duration of the test run. The second one, known as progressive-stress ALT, involves gradually increasing the stress that is applied to a test product over time. The third type of test condition change is known as the step-stress ALT, and it occurs when a certain number of failures occur or at a specific period. In situations where it is not possible to assume that the acceleration factor is known, the partially ALT (PALT) is a suitable option for conducting the life test. The experimental units are operated at both use and accelerated settings in a PALT, and they are subjected to higher stress levels than typical in an ALT to shorten the time to failure. A statistical model that is suitable for the physical environment is used to extrapolate data obtained in such accelerated settings and predict the lifespan distribution under typical use conditions. Three forms of stress may be identified in PALT: step-stress, progressive-stress, and constant-stress. Step-stress and constant-stress PALT are two often employed techniques. Items under step-stress PALT are tested under both used and accelerated conditions (see2,3,4,5,6). In constant-stress PALT (CPALT), all test units are split into two groups, one of which is tasked with working under used conditions and the other under accelerated conditions.

Numerous writers have examined CPALTs, in which items are tested at either normal use or accelerated conditions. The problem of CPALT estimation with different censored data using different distributions was studied in subsequent studies. Bai and Chung7 estimated the scale parameter and the acceleration factor for exponentially distributed lifetimes under Type-I censoring using the maximum likelihood (ML) technique. Bai et al.8 examined the optimum design and estimation for the log-normal distribution using CPALT with Type-I censored data. Hassan9 discussed the estimation of the exponentiated exponential distribution in CPALT using Type II censoring. Using Type-I censored data in CPALT, the optimum design problem for the inverse Weibull distribution has been examined by Ismail10. Using progressive Type-II censoring, Abdel-Hamid11 examined the issue of estimating the Burr XII distribution based on CPALT. Ismail et al.12 investigated the issue of optimal design for Pareto distribution in CPALT by employing Type-I censoring. Using Type-I censoring, Kamal et al.13 examined the CPALT plan with the assumption that test item life under usage conditions follows an inverted Weibull distribution. Abushal and Soliman14 studied CPALT using progressive censoring under the Pareto distribution. Hassan et al.15 obtained the ML estimates (MLEs) of parameters and acceleration factor in CPALT using multiple censoring data. Ahmad et al.16 studied the Bayesian estimation of the exponentiated Weibull model for CPALT using progressive censoring. Li and Zheng17 investigated CPALT in the context of the Gompertz distribution with Type-I censoring. Ismail and Tamimi18 examined the optimum design and estimation for the inverse Weibull distribution using CPALT with Type-I censored data. Mahmoud et al.19 used a Type-II censored sample to examine the estimation issues of modified Weibull distributions based on CPALT. The CPALT competing failure model from the Weibull distribution under Type I and Type II censoring was examined by Hassan et al.20 in their estimate issue analyses. Ahmadini et al.21 investigated the estimation problems of the Fréchet distribution based on CPALT using a Type-I censored sample. Based on CPALT, Lone et al.22 constructed the Bayesian prediction of the Gompertz distribution under CPALT. For the Kumaraswamy distribution, Almalki et al.23 investigated CPALT under adaptive type-II progressive censoring. The CPALT, under type-II progressive censoring, for an inverted generalized linear exponential distribution was examined by Mahmoud et al.24. Estimating the parameters of the Lomax distribution using a CPALT under progressive first failure type-II censored data was investigated by Eliwa and Ahmed25. For more recent studies. the reader can refer to26,27,28,29,30.

In statistics, parameter estimation is essential, and most of the time, estimating parameters starts with the ML method. This approach is well-liked because of its straightforward and understandable formulation. Lehmann and Casella31 showed that the estimators produced by this approach have a normal distribution and are asymptotically consistent. Nonetheless, there are alternative, widely-utilized estimating techniques in the literature. The techniques include Cramér-von-Mises estimation (CME), Anderson-Darling estimation (ADE), ordinary least squares estimation (OLSE), weighted least squares estimation (WLSE), maximum product of spacing estimation (MPSE), and Bayesian estimation (BE). While these approaches, except for ML estimation (MLE), lack strong theoretical characteristics, in some circumstances they can yield more accurate estimates of the unknown parameters. Using complete data, only one study was provided by Radwan and Alenazi32 using various estimation techniques based on CPALT. They obtained the parameter and acceleration factor estimators of the Chen distribution in CPALT using different classical methods, including MLE, OLSE, ADE, CME, WLSE, MPSE, percentile estimation, and right tail-ADE.

The study's main objective is to address the problem of different CPALT-based estimating methods that use complete data. This is due to many different natural phenomena, engineering problems, and medical procedures that generate significant amounts of complete real data that are vital to our way of life. The aforementioned suggests that the topic of different CPALT-based estimating techniques using complete, available real data is quite relevant. In this study, seven different estimating techniques for CPALT of power half-logistic distribution (PHLD) are investigated. The suggested methods are ADE, MPSE, MLE, OLSE, CME, WLSE, and BE. Further, the approximate confidence intervals (ACIs) based on MLE and the Bayesian credible intervals (BCIs) are investigated. We study how the estimators of the different parameters and acceleration factor behave for different sample sizes and for different parameter values. Further, we develop a guideline for choosing the best estimation method to estimate the parameters and the acceleration factor of the PHLD using CPALT, which we think would be of deep interest to applied statisticians and reliability engineers.

This paper is structured as follows: A description and fundamental presumptions of the model are given in Sect. "Model description and basic assumptions". Seven estimation techniques for investigating the parameters and acceleration factor are covered in Sect. Methods of estimation. A simulation study is conducted in Sect. "Simulation study" to evaluate how well these strategies function for the provided model. Two authentic data sets are used in Sect. "Data analysis" to demonstrate the importance of the PHLD. Lastly, some closing thoughts are provided in Sect. "Summary and conclusion".

Model description and basic assumptions

In most applied sciences, including engineering, economics, insurance, and biological science, statistical analysis and modeling of lifetime data are crucial. Numerous continuous distributions, such as the exponential, Lindley, gamma, log normal, half logistic, and Weibull have been introduced in the statistical literature for the modelling of lifetime data. The analysis of lifetime and reliability data has made considerable use of the power half-logistic distribution. The half logistic distributed random variable X with scale parameter a, and shape parameter b was introduced by Krishnarani33. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the PHLD is given by:

The CDF (1) reduced to half-logistic distribution for b = 1. The probability density function (PDF) of the PHLD is given by:

The survival function (SF) and hazard rate function (HF) of the PHLD are, respectively, given by:

Plots of the PDF and HF of the PHLD are represented in Fig. 1 for some selections of the distribution parameters. It can be noted that the density function provides some asymmetric and semi symmetric shapes, see the case of \(a = 0.6\) and \(b = 2.3\). The HF has an increasing behavior, decreasing, and reversed J-shaped depending on the parameter’s values.

The PHLD is a flexible statistical distribution that has gained considerable popularity for analyzing lifetime and reliability data for several reasons:

-

1.

The PHLD is a versatile distribution that can model a wide range of lifetime distributions, including symmetric and asymmetric distributions. This flexibility allows it to capture various shapes of failure distributions observed in real-world data. The PHLD has been successfully applied in various fields, including reliability engineering, survival analysis, and lifetime data analysis, making it a widely accepted distribution in these domains. To confirm that PHLD is a flexible model, see Krishnarani33. Also, this model is fitting different data sets as follows: Data I is COVID-19 data by Abu El Azm et al.34, Data II is time between failures of secondary reactor pumps by Suprawhardana and Prayoto35, and Data III is active repair time for 40 air bone communication transceivers by Oguntunde et al.36.

-

2.

The parameters of the PHLD have meaningful interpretations, making it easier to understand the distribution's characteristics. Specifically, the shape parameter governs the tail behavior of the distribution, while the scale parameter determines the spread of the distribution (see Fig. 1).

-

3.

The PHLD is relatively robust against outliers and deviations from the assumed distributional form, making it suitable for analyzing data with varying degrees of complexity or uncertainty (see Figs. 2, 3, and 4).

-

4.

The PHLD has several desirable statistical properties, such as closed-form expressions for moments, CDF, PDF, SF, and HF, see Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), respectively.

Table 1 discussed estimate (Esti) based on the MLE of the PHLD parameters for aforementioned each data set with standard error (StEr), and different measures of goodness of fit as: AIC (Akaike information criterion), BIC (Bayesian information criterion), CAIC (Consistent AIC), HQIC (Hannan-Quinn information criterion), Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance (KSD) with the corresponding p-value (PVKS), CMT (Cramér-von-Mises test) and ADT (Anderson–Darling test). Also, Figs. 2, 3, 4 contain the boxplot, the total time test (TTT), hazard rate estimated, CDF, PDF, and PP plots for PHLD based on Data Sets I, II and III, respectively. Figure 5 shows the likelihood profile of the PHLD parameters for each data set.

Based on the previous results, particularly the KST, we observe that the PVKS is greater than 0.05. This means that the PHLD fits different data for future use, suiting the PHLD adequately.

We use the following assumptions for the estimation under CPALT and PHLD.

-

1.

The lifetimes of test units are independent and identically distributed (iid), and they follow the PHLD with the CDF (1), PDF (2), SF (3) and HF (4).

-

2.

The test units' lifetimes are iid, according to the PHLD under the acceleration condition. The formula for the HF of the test unit is h2(z) = \(\delta\) h1(z), where the acceleration factor is \(\delta\) > 1. So, the HF of the PHLD, based on (4), under the accelerated condition is as follows: \(h_{2} (z;\phi ) = \frac{{ab\delta z^{b - 1} e^{{az^{b} }} }}{{(1 + e^{{az^{b} }} )}}\,,\) where \(\phi = (a,b,\delta )^{T}\) is the set of parameters. Afterwards, the SF of unit items under acceleration condition is given by: \(\overline{F}_{2} (z;\phi ) = e^{{ - \int\limits_{0}^{z} {h_{2} (z;\phi )dz} }} = \left( {\frac{2}{{1 + e^{{az^{b} }} }}} \right)^{\delta } .\)

Furthermore, the CDF, and the PDF of unit items under acceleration condition may be expressed as:

$$F_{2} (z;\phi ) = 1 - \left( {\frac{2}{{1 + e^{{az^{b} }} }}} \right)^{\delta } ,\,\,\,z > 0,$$(5)and

$$f_{2} (z;\phi ) = \frac{{2^{\delta } ab\delta z^{b - 1} e^{{a\,z^{b} }} }}{{(1 + e^{{a\,z^{b} }} )^{\delta + 1} }},\,\,z > 0.$$(6) -

3.

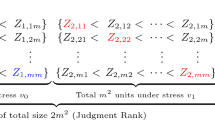

Using the CPALT, the total size of units is divided into two groups: q1 units for use condition and q2 units for accelerated condition. Let the lifetime Zh,k, k = 1,2, … , qh, h = 1, 2 be two complete samples from the PHLD. The lifetime of an item tested at use conditions is denoted by Z1k, while the lifetime of an item tested at accelerated conditions is denoted by Z2k. The two lifetimes Z1k and Z2k are pairwise statistically independent.

Methods of estimation

In this section, different classical methods of estimation are employed to get the parameter and acceleration factor estimates for the PHLD under CPALT.

Maximum likelihood estimation

In this subsection, the MLE is applied to obtain the estimators of the unknown parameters and acceleration factor under CPALT. The likelihood function of CPALT for PHLD under complete data can be obtained as:

The log-likelihood function of (7) based on (2) and (6) can be written as follows:

The normal equations of the unknown parameters b, a and the accelerated factor \(\delta\) can be given as:

and

The three aforementioned Eqs. (8–10) do not have a closed-form solution; hence, the MLEs can be obtained using a numerical methodology by employing approximations, as in the R program, by the “optim” function for log-likelihood.

Additionally, for evaluating the estimated variance–covariance matrix and related ACIs of MLEs, the observed Fisher information matrix is specified as follows:

Note that the second-order partial derivative equations are defined as follows:

The estimated standard normal distribution was used to derive the (1 − \(\upsilon\)) 100% ACIs, which are given by

where \(Z_{{^{{{\upsilon \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\upsilon 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}}} }}^{{}}\) denoted the upper \({\upsilon \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\upsilon 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}\) percent point of standard normal distribution.

Minimum distances estimators

This sub-section considers CME and ADE by minimization of the goodness-of-fit statistics, i.e., minimizing the distance between the theoretical and empirical CDFs with respect to a, b, and \(\delta .\)

Cramer–von Mises estimators

MacDonald37 offered empirical evidence showing the estimator's bias is less than that of the other minimal distance estimators, which supported our selection of CM type minimum distance estimators. This method will be used to estimate the acceleration factor \(\delta\) of the PHLD under complete data, as well as the unknown parameters a, and b, using CPALT. To do this, consider the lifetimes Z(hk), k = 1,2,…, qh, and h = 1, 2 as two full ordered samples with CDF \(F_{h} \left( {z_{(hk)} } \right)\) from the PHLD under CPALT. Therefore, by minimizing \(\zeta\) with respect to a, b, and \(\delta ,\) the CME of a, b, and \(\delta\) are obtained as follows:

Alternatively, the CME of a, b, and \(\delta\) can be obtained by solving the following nonlinear equations in place of using Eq. (11) as:

and

and

Anderson–Darling estimators

In place of statistical tests, Anderson and Darling38 developed a test to identify deviations from the normal distribution in sample distributions. This sub-section provides ADE for the parameters and acceleration factor of the PHLD under CPALT. Suppose that Z(hk), \(k = 1,2,...,q_{h}\), \(h = 1,2\) are two full-ordered samples from the PHLD in the CPALT.

The ADE of the parameters a, b and acceleration factor \(\delta ,\) in the CPALT model is produced by minimizing the function \({\text{A}}^{*}\) as below:

Instead of (15), the non-linear equations listed below can be solved to get the ADEs as

where \(\vartheta_{1} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{2} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.),\) \(\vartheta_{3} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{4} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) and \(\,\vartheta_{5} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) are given in Eqs. (12)–(14), respectively.

Method of maximum product spacing’s

This subsection uses the MPS approach established by Refs39,40 to estimate the PHLD under complete data using CPALT. A similar technique was separately developed by Ranneby41 as an approximation to the Kullback–Leibler information measure.

Suppose that Z(hk), k = 1,2,…, qh , h = 1, 2 are two complete-ordered samples with CDF \(F_{h} \left( {z_{(hk)} } \right)\) taken from the PHLD under CPALT. The following function must be maximized with respect to a, b and \(\delta ,\) in order to determine their MPSE

where \(\Delta_{hk}\) is the uniform spacings of a random sample from the PHLD under CPALT and is defined by

Consequently, by using (1) and (5) in (16), we have

The following nonlinear equations can be numerically solved to get the MPSE of a, b and \(\delta\) as

and

where \(\vartheta_{1} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{2} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.),\) \(\vartheta_{3} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{4} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) and \(\,\vartheta_{5} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) are given in Eqs. (12)–(14).

Ordinary least and weighted least squares estimators

In this subsection, the OLSE and WLSE of a, b and acceleration factor \(\delta ,\) for the PHLD under CPALT are obtained. Suppose that Z(hk), k = 1,2,…, qh , h = 1, 2 be the complete ordered samples have CDFs \(F_{h} \left( {z_{(hk)} } \right)\) from the PHLD under CPALT. Hence, by minimizing the following function with respect to a, b and \(\delta\) as

where \(\pi_{h} = 1,\) in case of OLSEs and \(\pi_{h} = \frac{{(q_{h} + 1)^{2} (q_{h} + 2)}}{{k(q_{h} - k + 1)}},\) in the case of the WLSE.

An alternative way to (17), the OLSE and WLSE of a, b and \(\delta ,\) can be produced by solving the following equations numerically:

and

where \(\vartheta_{1} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{2} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.),\) \(\vartheta_{3} (\,z_{(1k)} \left| {a,b} \right.),\,\vartheta_{4} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) and \(\,\vartheta_{5} (\,z_{(2k)} \left| \phi \right.)\) are given in Eqs. (12)–(14).

Bayesian estimation

This sub-section presents the Bayes estimators for the unknown parameters and the acceleration factor of the PHLD under the assumption that the random variables a, and b, have independent gamma prior distributions, and the independent parameter \(\delta\) has a truncated gamma distribution. Assumed that a ∼ Gamma \((\alpha_{1} ,\beta_{1} ),\) b∼ Gamma \((\alpha_{2} ,\beta_{2} ),\) and \(\delta - 1\)∼ Gamma \((\alpha_{3} ,\beta_{3} ),\) then the joint prior density of a, b, and \(\delta\) can be written as follows:

The gamma prior density was first used by DeGroot and Goel42 for the parameter of acceleration factor \(\delta .\) In this case, every hyper-parameter \(\alpha_{1} ,\alpha_{2} ,\alpha_{3} ,\beta_{1} ,\beta_{2} ,\) and \(\beta_{3}\) is non-negative and known. Due to the great flexibility of the gamma distribution (see, for example, Dey et al.43), and (Kundu and Howlader44), independent gamma priors have been utilized in the Bayesian analysis. Using the Bayes theorem, the joint posterior distribution of a, b, and \(\delta\) is provided by combining the joint prior distribution (18) with the likelihood function (7) as

where

Under the squared error loss function (SELF), the Bayes estimator of the function of parameters \(g^{*} (\phi )\) is given by

In general, it is not possible to obtain the integral provided by Eq. (20) in a closed form.

In this instance, we create samples from the posterior distributions using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach, after which we calculate the Bayes estimators for each of the individual parameters and acceleration factor.

Selecting among the many different MCMC schemes that are available might be challenging. Gibbs sampling and the more generic Metropolis within Gibbs samplers are significant subclasses of MCMC techniques. The MCMC technique has an advantage over the MLE method in that by building the probability intervals based on the empirical posterior distribution, we can always obtain an acceptable interval estimate of the parameters. With the MLE, this is frequently not available. In fact, by using a kernel estimate of the posterior distribution, the MCMC samples may be utilized to fully characterize the posterior uncertainty regarding the parameters a, b, and \(\delta .\) This also holds for any function that depends on the arguments. The conditional posterior densities of a, b, and \(\delta\) are as follows:

where \(\phi_{ - a}\) stands for a vector of the unknown parameters except the parameter a. Furthermore, using the approach suggested by Chen and Shao40, we obtain the 95% two-sided BCIs for the set of unknown parameter as \(\left[ {\phi_{0.025N:N} ,\phi_{0.975N:N} } \right]\), where N is the length of the MCMC result.

The following Metropolis–Hastings (MH)-within-Gibbs sampling steps can be used to obtain samples of a, b, and \(\delta\):

-

1.

Start by initializing an initial estimate, denoted as \(\phi^{(0)} \equiv (\hat{a},\hat{b},\hat{\delta }).\)

-

2.

Set the iteration index to t = 1.

-

3.

Generate a candidate point \(\phi^{ * }\) using a normal proposal distribution \(q(\phi ) = N(\hat{\phi },{\text{var}} (\hat{\phi })).\)

-

4.

For the given candidate point \(\phi^{ * } ,\) compute the acceptance probability.

\(A(\phi_{1}^{(t - 1)} ,\phi_{1}^{ * } ) = \min \left[ {1,\frac{{g\left( {a^{ * } ,a^{t - 1} ,\delta^{t - 1} \left| {\mathop{x}\limits_{\rightharpoondown} } \right.} \right)q(a^{ * } )}}{{g\left( {a^{t - 1} ,a^{t - 1} ,\delta^{t - 1} \left| {\mathop{x}\limits_{\rightharpoondown} } \right.} \right)q(a^{t - 1} )}}} \right],\) and repeat this probability for all parameters to obtain \(A(\phi_{{}}^{(t - 1)} ,\phi_{{}}^{ * } ).\)

-

5.

Generate a sample from a uniform distribution, i.e., \(u\sim U\left(\text{0,1}\right)\).

$${\text{If}}\;\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {u \le A(\phi_{{}}^{(t - 1)} ,\phi_{{}}^{ * } )} & {accept\,\phi_{{}}^{ * } \, = \phi_{{}}^{(t)} \,\,} \\ {u \le A(\phi_{{}}^{(t - 1)} ,\phi_{{}}^{ * } )} & {accept\phi_{{}}^{t} \, = \phi_{{}}^{(t - 1)} .} \\ \end{array} } \right.$$ -

6.

Increment the iteration index: t = t + 1, and repeat Steps 2–5 M times until obtaining M samples, resulting in \((a^{t - 1} ,a^{t - 1} ,\delta^{t - 1} )\) for t = 1, 2,…, M.

Simulation study

The primary objective of this section is to compare parameter estimates using mean squared error (MSE) and absolute bias (ABias) for different point estimates. For different values of \({q}_{1}\) and \({q}_{2}\) (representing the sample sizes for use and accelerated conditions) as (20, 15), (50, 40), (100, 120), and (200, 150), a large number (\(N = 10,000\)) of complete samples are generated from the PHLD under both use and accelerated conditions. The true values of the parameters \(a, b\), and \(\delta\) are considered as follows: In Table 2: (\(a, b\),\(\delta\)) = (1.2, 1.5, 1.1), (1.2, 1.5, 2), and (1.2, 1.5, 3). In Table 3: (\(a, b\),\(\delta\)) = (0.5, 1.5, 1.1), (0.5, 1.5, 2), and (0.5, 1.5, 3). In Table 4: (\(a, b\),\(\delta\)) = (0.5, 0.6, 1.1), (0.5, 0.6, 2), and (0.5, 0.6, 3). In addition, the upper, lower, length of the point estimates of the ACIs (LCI) and BCIs (LCCI) as well as the coverage probabilities (CPs) with a 95% confidence level are computed. Values of CPs, upper, lower, LCIs, and LCCIs are provided in Tables 5, 6, 7.

To conduct the numerical analysis, the following steps are necessary:

-

1.

Create two separate sets of random samples, each with sizes represented by \({q}_{1}\) and \({q}_{2}\), drawn from the uniform (0,1) distribution utilizing the “runif()” function in R program. These random samples are denoted as \(({U}_{11},{U}_{21}),({U}_{12},{U}_{22}), ..., \left({U}_{1{q}_{1}},{U}_{2{q}_{2}}\right)\). By varying the values of \({q}_{1}\), \({q}_{2}\), as well as different parameters and acceleration factors, the two samples are generated from the inverse CDF in Eqs. (5), and (1), respectively as follows:

$$z_{1} = \left[ {\frac{1}{a}\ln \left( {\frac{2}{{1 - U_{1i} }} - 1} \right)} \right]^{1/b} ;\,\,\,\,\,i = 1,2,...,q_{1} .\quad \& \quad z_{2} = \left[ {\frac{1}{a}\ln \left( {\frac{2}{{\left( {1 - U_{2i} } \right)^{1/\delta } }} - 1} \right)} \right]^{1/b} ;\,\,\,\,\,\,i = 1,2,...,q_{2} .$$ -

2.

Using the outcomes using the MLEs, MPSEs, OLSEs, WLSEs, CMEs, ADEs, and BEs, various estimates of the unknown parameters and acceleration factor are computed. This is accomplished either by employing the “optim()” function in R or by utilizing the BFGS (Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) algorithm.

-

3.

Perform Steps 1 and 2 repeatedly for a total of 10,000 iterations.

-

4.

Calculate the average of ABias, MSE, CPs, upper, lower, LCIs, and LCCIs of the different parameter estimates and accelerated factor estimates of the PHLD.

The outcomes derived from the numerical comparison analysis of various methods using MSEs and ABias for all estimates are showcased in Tables 2 through 4. The outcomes of the CPs, upper, lower, LCIs, and LCCIs of all estimates are listed in Tables 5, 6, 7. From these tables we conclude the following:

-

The MSEs and ABias decrease for all estimates as the values of \({q}_{1}\) and \({q}_{2}\) increase, as anticipated, as seen in Tables 2 through 4.

-

The MLEs show notable improvement with smaller values of MSE and ABias, making them one of the top classical estimation method choices for large sample sizes concerning parameters.

-

In general, the MPSEs perform better than other classical estimates (MLE, CME, ADE, OLSE, WLSE) with smaller MSE and ABias values.

-

In most cases, Bayesian estimation exhibits superior performance compared to alternative techniques, considering both MSE and ABias.

-

Based on the results of the simulation study, we recommend utilizing Bayesian, MPSE, and MLE for CPALT with complete data, while prioritizing consideration of MSEs and ABias.

-

We note from the results of the confidence intervals that the larger the sample size, the shorter the length of the interval, and this indicates the accuracy of the results and the convergence of the results as the sample size increases. The BCIs have a higher coverage probability than the ACIs

Data analysis

In this section, different data sets are used to illustrate the suggested estimators and some measures of goodness of tests are considered.

Data set 1: Comprises chronological failure times. It encompasses the recorded failure times of ten steel samples subjected to four different stress levels. This section focuses on data representing only two stress levels, specifically 0.87 and 0.99 (106 psi), which were adjusted to suit the problem under investigation. The data can be displayed as follows: Stress (106 psi) the use condition (0.87) is 1.679, 2.20, 2.519, 3.009, 3.909, 4.70, 7.53, 14.70, 27.8, and 37.4. While the accelerated condition (0.99) is 0.80, 1.00, 1.37, 2.25, 2.95, 3.70, 6.07, 6.65, 7.05, and 7.37.

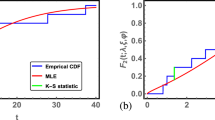

Initially, the MLE is applied to the complete dataset to assess the suitability of the PHLD for fitting both the normal and accelerated conditions. The AIC, BIC, CAIC, HQIC, KSD with the PVKS, CMT, and ADT are computed for both conditions, and the outcomes are outlined in Table 8. Results indicate that the PHLD adequately fits the data for both normal and accelerated conditions. Figure 6 illustrates this further by presenting a boxplot of the dataset, a TTT plot of the dataset, a fitted hazard rate, the empirical CDF alongside the fitted CDF, a histogram of the data with a PDF, and a PP plot of the PHLD obtained through MLE for used conditions. Figure 7 illustrates this further by presenting a boxplot of the dataset, a TTT plot of the dataset, a fitted hazard rate, the empirical CDF alongside the fitted CDF, a histogram of the data with PDF, and a PP plot of the PHLD obtained through MLE for accelerated conditions.

Subsequently, various estimation methods outlined in ML, MPS, OLS, WLS, CM, AD, and Bayesian are utilized to derive estimates of the unknown parameters and the acceleration factor under CPALT, utilizing the ordered failure times data. These estimates, derived from real datasets using different estimation methods, are summarized in Table 9. Additionally, the survival and hazard rates of the PHLD with the mean average of ordered times to failure data are examined under both conditions as seen in Table 9.

Also, the StErs have been obtained for parameters of PHLD by MLE, MPS, and Bayesian estimation methods based on the SELF in Table 10. Based on these results in Table 10, the Bayesian estimation method has the smallest StEr compared to the ML and MPS methods. To validate the MLE, a likelihood profile for the PHLD is plotted in Fig. 8. This graph illustrates how the natural logarithm of the likelihood function, representing the probability of observing the ordered times to failure data given various parameter values, changes as the parameter varies. This information is crucial for comprehending the behavior and uncertainty associated with the estimated parameter. By analyzing the likelihood profile alongside the natural logarithm of the likelihood, insights into the parameter of the likelihood function and the behavior of the estimated PHLD parameters can be gained. Peaks in the likelihood profile correspond to the MLE of the PHLD parameters, while the natural logarithm of the likelihood provides additional information regarding the curvature of the likelihood function around these peaks.

MCMC is a highly effective computational method utilized to estimate the intricate posterior density of PHLD parameters. When conducting an MCMC simulation, it's vital to examine the trajectory of the Markov chain and its convergence to guarantee the accuracy of the outcomes. Evaluating the trace plot and convergence diagnostics is crucial in verifying MCMC findings and ensuring the dependability of Bayesian inference, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Dataset 2: Encompasses the breakdown times of insulating fluids used in high-voltage tests. After necessary modifications to align with the specific research problem, this dataset is scrutinized in this section. The focus is on two stress levels, namely 30 and 32 kV, designated as the normal and accelerated conditions, as indicated as follows: Use condition (30) is 7.74, 17.05, 20.46, 21.02, 22.66, 43.40, 47.30, 139.07, 144.12, 175.88, and 194.90. Accelerated condition (32) is 0.27, 0.40, 0.69, 0.79, 2.75, 3.91, 9.88, 13.95, 15.93, 27.80, 53.24, 82.85, 89.29, 100.58, and 215.10.

Initially, MLE is applied to the complete dataset to assess the suitability of the PHLD for fitting the data for both normal and accelerated conditions in Table 11. The KSD with corresponding p-values, AIC, BIC, CAIC, HQIC, CMT, and ADT are computed for each condition, as outlined in Table 11. Results from Table 11 suggest a favorable fit of the PHLD to the data under both conditions.

Additionally, Fig. 10 illustrates this further by presenting boxplot of dataset, TTT plot of dataset, fitted hazard rate, the empirical CDF alongside the fitted CDF, histogram of data with PDF, and PP plot of the PHLD obtained through MLE for standard conditions. Figure 11 illustrates this further by presenting boxplot of dataset, TTT plot of dataset, fitted hazard rate, the empirical CDF alongside the fitted CDF, histogram of data with PDF, and PP plots of the PHLD obtained through MLE for accelerated conditions.

Various estimation techniques, ranging from ML, MPS, OLS, WLS, CM, AD, to Bayesian, are utilized to determine the unknown parameters and accelerated factor under the CPALT framework. Table 12 presents the estimates derived from real datasets using different estimation methods for the oil breakdown times of insulating fluid. Also, it includes the survival and hazard rate estimates of the PHLD with the mean average of the oil breakdown times of insulating fluid data under both conditions.

Furthermore, the StErs for the parameters of the PHLD have been derived using ML, MPS, and Bayesian estimation techniques employing the SELF, as shown in Table 13. From the data presented in Table 13, it is evident that the Bayesian estimation method yields the smallest standard errors compared to the ML and MPS methods.

To check the MLE, we plotted the likelihood profile for PHLD in Fig. 12. It represents how the log-likelihood function, which quantifies the probability of observing the data given different values of a parameter, changes as the parameter varies. This information is crucial for understanding the behavior and uncertainty associated with the parameter being estimated. When examining a likelihood profile alongside the log-likelihood, one can gain insights into the parameters of the likelihood function and the behavior of the PHLD parameter being estimated. Peaks in the likelihood profile correspond to the MLE of the PHLD parameter, while the log-likelihood provides additional information about the curvature of the likelihood function around these peaks.

MCMC is a powerful computational technique used for estimating the complex posterior density of PHLD parameters. When running an MCMC simulation, it's crucial to assess the trace of the Markov chain and its convergence to ensure the validity of the results. Monitoring the trace plot and assessing convergence diagnostics are essential steps in validating MCMC results and ensuring the reliability of Bayesian inference, which is obtained in Fig. 13.

Summary and conclusion

The PALTs are utilized when the findings of accelerated life testing cannot be applied to usage scenarios. The problem of various estimating procedures in CPALT with full data is covered in this paper. It is considered that the test item's lifespan distribution will resemble a PHLD. The PHLD's acceleration factor and distribution parameters may be estimated using a variety of traditional and Bayesian estimation methods. Among these methods are Bayesian estimation, ADE, MLE, CME, OLSE, WLSE, and MPSE. A simulation study is provided in order to assess the outcomes of the various estimating techniques based on absolute average bias, mean squared error, coverage probability, and average length. This research indicates that when utilizing the minimal values for mean squared error and average bias, the maximum product of spacing estimation method is often the most efficient approach out of all the available possibilities. The Bayesian technique performs better than alternative approaches in most cases. The lowest interval length and higher coverage probability of the BCIs make them better than the ACIs in obtaining confidence intervals. For purposes of illustration, two real data sets are analyzed. The suggested approaches are feasible and appropriate for several engineering-related issues, as demonstrated by an analysis of the two real data sets. In further work, the aforementioned approaches and other classical procedures can be used to investigate the reliability function and the unknown parameters across different probability distributions.

Data availability

The references of the data sets used in this study are presented in the article.

References

Nelson, W. Accelerated Testing: Statistical Models, Test Plans and Data Analysis (John Wiley, 1990).

Abd-Elfattah, A. M., Hassan, A. S. & Nassr, S. G. Estimation in step-stress partially accelerated life tests for the Burr type XII distribution using type I censoring. Stat. Methodol. 5(6), 502–514 (2008).

Ismail, A. A. Optimum failure-censored step-stress life test plans for the Lomax distribution. Strength Mater. 48, 437–443 (2016).

Lone, S. A. & Rahman, A. Step stress partially accelerated life testing plan for competing risk using adaptive type-i progressive hybrid censoring. Pak. J. Stat. 33, 237–248 (2017).

Alam, I. & Ahmed, A. Parametric and interval estimation under step-stress partially accelerated life tests using adaptive type-II progressive hybrid censoring. Ann. Data Sci. 1–13, 2020 (2020).

Bantan, R. et al. Bayesian analysis in partially accelerated life tests for weighted Lomax distribution. Comput. Mater. Contin. 68(3), 2859–2875. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2021.015422 (2021).

Bai, D. S. & Chung, S. W. Optimal design of partially accelerated life tests for the exponential distribution under type-I censoring. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 41(3), 400–406 (1992).

Bai, D. S., Chung, S. W. & Chun, Y. R. Optimal design of partially accelerated life tests for the lognormal distribution under Type-I censoring. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 40(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0951-8320(93)90122-F (1993).

Hassan, A. S. Estimation of the generalized exponential distribution parameters under constant stress partially accelerated life testing using type I censoring. Egypt. Stat. J. 51(2), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.21608/ESJU.2007.313449 (2007).

Ismail, A. A. Planning constant stress partially accelerated life tests with type II censoring: The case of Weibull failure distribution. Int. J. Stat. Econ. 3, 39–46 (2009).

Abdel-Hamid, A. H. Constant stress partially accelerated life tests for Burr type XII distribution with progressive type II censoring. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 53(7), 2511–2523 (2009).

Ismail, A. A., Abdel-Ghaly, A. A. & El-Khodary, E. H. Optimum constant-stress life test plans for Pareto distribution under type-I censoring. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 81(12), 1835–1845. https://doi.org/10.1080/00949655.2010.506440 (2011).

Kamal, M., Zarrin, S. & Islam, A. U. Constant stress partially accelerated life test design for inverted Weibull distribution with Type-I censoring. Algorithms Res. 2(2), 43–49 (2013).

Abushal, T. A. & Soliman, A. A. Estimating the Pareto parameters under progressive censoring data for constant partially accelerated life tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 85(5), 917–934 (2015).

Hassan, A. S., Assar, M. S. & Zaky, A. N. Constant-stress partially accelerated life tests for inverted Weibull distribution with multiple censored data. Int. J. Adv. Stat. Probab. 3(1), 72–82 (2015).

Ahmad, A. A., Soliman, A. A. & Yousef, M. M. Bayesian estimation of exponentiated Weibull distribution under partially acceleration life tests. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 39, 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40840-015-0170-9 (2016).

Li, X. & Zheng, H. Estimation and optimum constant-stress partially accelerated life test plans for Gompertz distribution with Type-I censoring. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods https://doi.org/10.1080/03610926.2013.839041 (2015).

Ismail, A. & Tamimi, A. Optimum constant-stress partially accelerated life test plans using type-I censored data from the inverse Weibull distribution. Strength Mater. 49, 1–9 (2018).

Mahmoud, M. A., El-Sagheer, R. M. & Abou-Senna, A. M. Estimating the modified Weibull parameters in presence of constant-stress partially accelerated life testing. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 17, 242–260 (2018).

Hassan, A. S., Pramanik, S., Maiti, S. & Nassr, S. G. Estimation in constant stress partially accelerated life tests for Weibull distribution based on censored competing risks data. Ann. Data Sci. 7(1), 45–62 (2020).

Ahmadini, A. A. H. et al. Estimation of Constant Stress Partially Accelerated Life Test for Fréchet Distribution with Type-I Censoring. Math. Probab. Eng. 2021, 9957944 (2021).

Lone, S. A., Panahi, H. & Shah, I. Bayesian prediction interval for a constant-stress partially accelerated life test model under censored data. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 15(1), 1178–1187. https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2021.2023847 (2021).

Almalki, S. J., Farghal, A. A., Rastogi, M. K. & Abd-Elmougod, G. A. Partially constant-stress accelerated life tests model for parameters estimation of Kumaraswamy distribution under adaptive type-II progressive censoring. Alex. Eng. J. 61(7), 5133–5143 (2022).

Mahmoud, M. A. W., Ghazal, M. G. M. & Radwan, H. M. M. Constant-partially accelerated life tests for three parameter distribution: Bayes inference using progressive type-II censoring. J. Stat. Appl. Probab. 11(1), 15–28 (2022).

Eliwa, M. S. & Ahmed, E. A. Reliability analysis of constant partially accelerated life tests under progressive first failure type-II censored data from Lomax model: EM and MCMC algorithms. AIMS Math. 8(1), 29–60. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2023002 (2022).

Dey, S., Wang, L. & Nassar, M. Inference on Nadarajah-Haghighi distribution with constant stress partially accelerated life tests under progressive type-II censoring. J. Appl. Stat. 49, 2891–2912 (2022).

Nassar, M. & Elshahhat, A. Statistical analysis of inverse Weibull constant-stress partially accelerated life tests with adaptive progressively type I censored data. Mathematics 11, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11020370 (2023).

Abd-El-Monem, A., Eliwa, M. S., El-Morshedy, M., Al-Bossly, A. & EL-Sagheer, R. M. Statistical analysis and theoretical framework for a partially accelerated life test model with progressive first failure censoring utilizing a power hazard distribution. Mathematics 11, 4323. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11204323 (2023).

Alrashidi, A. et al. Exponentiated gamma constant-stress partially accelerated life tests with unified hybrid censored data: Statistical inferences. Alex. Eng. J. 88, 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.12.066 (2024).

Alam, I., Kamal, M., Agarwal, T. & Mishra, A. A study on partially accelerated life test for the generalized inverse lindley distribution under multiple censored information. Thail. Stat. 22(1), 162–179 (2024).

Lehmann, E. & Casella, G. Theory of Point Estimation (Springer, 2003).

Radwan, H. M. M. & Alenazi, A. Different estimation techniques for constant-partially accelerated life tests of Chen distribution using complete data. Sci. Rep. 13, 15600. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42055-8 (2023).

Krishnaran, S. D. On a power transformation of half-logistic distribution. J. Probab. Stat. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2084236 (2016).

Abu El Azm, W. S., Almetwally, E. M., Naji AL-Aziz, S., El-Bagoury, A. A. A. H., Alharbi, R. & Abo-Kasem, O. E. A new transmuted generalized Lomax distribution: Properties and applications to covid-19 data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021 (2021).

Suprawhardana, M. S. & Prayoto, S. Total time on test plot analysis for mechanical components of the RSG-GAS reactor. Atom Indones 25(2), 81–90 (1999).

Oguntunde, P. E., Khaleel, M. A., Okagbue, H. I. & Odetunmibi, O. A. The Topp-Leone Lomax (TLLo) distribution with applications to airbone communication transceiver dataset. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 109, 349–360 (2019).

MacDonald, P. D. M. Comment on “an estimation procedure for mixtures of distributions” by Choi and Bulgren. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 33(2), 326–329 (1971).

Anderson, T. W. & Darling, D. A. Asymptotic theory of certain “goodness of fit” criteria based on stochastic processes. Ann. Math. Stat. 23(2), 193–212 (1952).

Cheng, R. C. H. & Amin, N. A. K. Maximum product of spacings estimation with applications to the log-normal distribution. University of Wales IST. Math. Rep. 45(3), 394–403 (1979).

Chen, M. H. & Shao, Q. M. Monte Carlo estimation of Bayesian credible and HPD intervals. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 8(1), 69–92 (1999).

Ranneby, B. The maximum spacing method. An estimation method related to the maximum likelihood method. Scand. J. Stat. 11(2), 93–112 (1984).

DeGroot, M. H. & Goel, P. K. Bayesian estimation and optimal designs in partially accelerated life testing. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 26(2), 223–235 (1979).

Dey, S., Ali, S. & Park, C. Weighted exponential distribution: Properties and different methods of estimation. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 85, 3641–3661 (2015).

Kundu, D. & Howlader, H. Bayesian inference and prediction of the inverse Weibull distribution for type-II censored data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 54, 1547–1558 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R226), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alomani, G.A., Hassan, A.S., Al-Omari, A.I. et al. Different estimation techniques and data analysis for constant-partially accelerated life tests for power half-logistic distribution. Sci Rep 14, 20865 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71498-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71498-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

E-Bayesian and Hierarchical Bayesian Stress-Strength Reliability Modeling under Partially Accelerated Life Testing

Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice (2026)

-

Utilizing unified progressive hybrid censored data in parametric inference under accelerated life tests

Scientific Reports (2025)