Abstract

Nanomechanical oscillators are an alternative platform for computation in harsh environments. However, external perturbations arising from such environments may hinder information processing by introducing errors into the computing system. Here, we simulate the dynamics of three coupled Duffing oscillators whose multiple equilibrium states can be used for information processing and storage. Our analysis reveals that, within experimentally relevant parameters, error correcting dynamics can emerge, wherein the system’s state is robust against random external impulses. We find that oscillators in this configuration have several surprising and attractive features, including dynamic isolation of resonators exposed to extreme impulses and the ability to correct simultaneous errors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanomechanical systems comprise mechanical elements which are sub-micron scale in at least one dimension1,2. These systems are increasingly being studied for a number of applications in sensing3,4,5, as well as for their ability to serve as an alternative platform for computation6. In the context of computing, nanomechanical oscillators are used to encode information in their mechanical motion7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, analogous to the role of electrical charge encoding information within semiconductor devices. Nanomechanical oscillators are advantageous for this application due to their readily accessible nonlinear responses and controllable oscillation properties15.

Compared to conventional semiconductor based computers, nanomechanical computers promise more efficient operation and longer lifespans in harsh environments, such as medical facilities, nuclear power plants, and outer space2,8,9,13,16,17. However, despite their robustness in harsh environments, nanomechanical logic elements remain vulnerable to transient errors arising from thermal effects, electromagnetic pulses, ionising radiation, or mechanical shock18. These types of transient bit-errors, which also occur frequently in conventional computers19, are often referred to as single-event upsets (SEUs)20,21. For nanomechanical logic, SEUs originate from an instantaneous impulse on the mechanical oscillator that is sufficiently large to shift the oscillator from one logical state to the other. In conventional computing systems, a common technique to mitigate the effects of SEUs is to use majority voting logic22. While there are many proposals and demonstrations of nanomechanical logic gates and memories in the literature7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, to date, no scheme exists to perform error correction in nanomechanical systems without first converting the information into the electrical domain.

A direct mechanical error correction scheme could be designed to leverage the collective behaviour of networks of nonlinear oscillators, such as those found in nanomechanical computing systems. These systems can often exhibit intricate emergent phenomena that cannot be predicted by extrapolating the behaviours of individual oscillators. For example, a network of unsynchronized oscillators will spontaneously synchronise once their coupling strength exceeds a critical threshold23. Such networks can also be designed to display robustness against noise, ensuring that local perturbations rarely alter the steady-state of the overall system24,25. An improved understanding of these behaviors has supported numerous applications in conventional information processing and communication, including algorithms for broadband network sharing26, enhanced cybersecurity27 and optical metrology28.

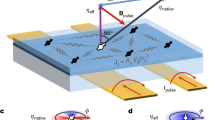

Inspired by these developments, in this work, we explore the potential to perform autonomous 3-bit majority voting error correction via a simple system of three all-to-all coupled nonlinear oscillators. Specifically, we study a system of oscillators with third-order nonlinearity, the dominant form of nonlinearity for many physical oscillators1, which is exposed to incident ionising radiation. We refer to the oscillators as Duffing oscillators and depict a number of their experimental implementations in Fig 1a. The dynamics of large networks of nonlinear oscillators in the presence of perturbations have been well documented under various names, including basin stability29,30,31, noise-induced bifurcations32,33, phase transitions in stochastic systems34,35. Here, we show that useful information processing can occur even with small systems of nonlinear oscillators with experimentally accessible parameters.

Specifically, our proposed system autonomously returns to its initial state after a perturbation, differentiating it from traditional majority-vote error correction schemes by operating without additional comparator circuitry, showing enhanced performance under extreme perturbations, and correcting simultaneous errors probabilistically. Indeed, a computational search over the parameter space reveals a wide region where collective error-correcting dynamics emerge. The realisation of an error-correcting phase for third-order nonlinear oscillators offers a novel approach to addressing SEUs, paving the way for fault-tolerant nanomechanical computing.

(a) Schematic of a single Duffing oscillator and its applications in various computing platforms. Images of a nanomechanical circuit, superconducting circuit, and optical circuit reproduced from Refs.8,36,37, respectively. (b) Frequency/drive response of Duffing oscillator. Solid (dashed) lines represent stable (unstable) solutions of the Duffing equation. Jumps between the stable solutions are labelled with up and down arrows. (c) Time dynamics of a driven, damped Duffing oscillator subject to an SEU. The parameters of the oscillator are given by: \(m = 10^{-12}\) kg, \(\Gamma = 10^{5}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\), \(\omega _0 = 10^{6}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\), \(\alpha = 3 \times 10^{22}\) \(\hbox {m}^{-2} s^{-2}\), \(\omega = 1.152 \times 10^{6}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\), \(F = 5 \times 10^{-7}\) N, \(\Delta p = 6 \times 10^{-12}\) \(\hbox {kg.m.s}^{-1}\). The oscillator is first initialised in the ‘0’ state, but then subject to an SEU which leads to a bit flip. The displacement is expressed in arbitrary units, such that the magnitude of a ‘1’ signal is 1.

Methods and results

The Duffing oscillator under study in this work is described by the following equation1:

where, for a mechanical oscillator, x is the displacement, m the mass, \(\Gamma \) the dissipation, \(\omega _0\) the resonant frequency, \(\alpha \) the strength of nonlinearity and F the amplitude of the sinusoidal drive provided to the system at frequency \(\omega \). At certain drive amplitudes and frequencies, the steady-state dynamics exhibit bistability1, with one stable solution corresponding to high displacement and the other corresponding to low displacement7. This bistability is shown in Fig. 1b for the case of spring hardening (\(\alpha \) >0), wherein the oscillation amplitude depends on the history of the drive frequency (left) and amplitude (right).

We use numerical methods to simulate the responses of Duffing oscillators to incident impulses from ionising radiation. Collision events are modelled as instantaneous changes to the momentum of the oscillators. By convention, we use high (low) displacements to represent binary ‘1’ (‘0’) signals (red/blue shaded regions in Fig. 1b), as proposed14 and recently demonstrated7 in nanomechanical logic gate implementations. Figure 1c illustrates the time dynamics of a single Duffing oscillator based on Eq. (1), with an impulse introduced at the time indicated by the dashed line. The momentum imparted on the oscillator by the impulse is denoted \(\Delta p\), which is introduced as a change in oscillator velocity in between simulation timesteps. The oscillator is initially prepared in a ‘0’ state but the impulse causes it to latch onto the ‘1’ state, which corresponds to an erroneous bit-flip.

Within a 3-bit majority voting algorithm, each bit is replicated three times; if one bit is affected by a SEU, then the algorithm corrects this error by assuming that the majority state of the 3 bits is correct. This is traditionally achieved through bit post-processing with a logic circuit. We propose an equivalent architecture that consists of three identical, equally forced, Duffing oscillators that are all linearly coupled (see Fig. 2a). Each individual oscillator is driven into the bistable region and represents a single logical bit. The coupling provides an additional avenue for driving that can be either large or small depending on the amplitude of the neighbouring oscillators. The equations of motion of these coupled oscillators are:

where \(\beta \) is the coupling constant between oscillators, and \(x_1\), \(x_2\), and \(x_3\) represent the displacement of oscillators 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

(a) Schematic of mechanical error correction system, composed of three coupled Duffing oscillators. This functions as a majority voting system and can correct for single SEUs. (b) Time dynamics of error correction device. The coupled oscillators are initialised in their ‘0’ states and after 4.7 periods of oscillation, an impulse is applied to the third oscillator. The third oscillator temporarily transitions into its ‘1’ state, but quickly equilibrates back. The parameters of the oscillator are given by: \(m = 10^{-12}\) kg, \(\Gamma = 10^{5}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\), \(\omega _0 = 10^{6}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\) , \(\alpha = 3 \times 10^{22}\) \(\hbox {m}^{-2}.s^{-2}\), \(\omega = 1.152 \times 10^{6}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\), \(F=1.048 \times 10^{-6}\) N, \(\Delta p = 6 \times 10^{-12}\) \(\hbox {kg.m.s}^{-1}\), \(\beta = 2 \times 10^{11}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-2}\). (c) Phase map of error correction device. The map is divided into four main regions, ‘1’ bias, ‘0’ bias, initialise and error correction. This map is produced using the same parameters as (b). The y-axis is normalised by \(F_{crit}\), which we define as the minimum drive force required to sustain a ‘111’ state. Here, \(F_{crit} = 1.68 \times 10^{-7} \) N at \(\omega = 8.3 \times 10^5\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\).

To determine the collective behaviour of the proposed error correcting network, we simulate its time dynamics for a range of different parameters and initial conditions. We search for emergent phases where the collective dynamics exhibit only two steady states (‘111’ and ‘000’), irrespective of when impulses occur and insensitive to small deviations in system parameters. We find that for specific sets of parameters, error correcting behaviour is possible. One example is shown in Fig. 2b, where each oscillator is initially prepared in the ‘0’ state, before oscillator 3 is subjected to an impulse of the same magnitude as that in Fig. 1c (dashed line). We see that the impulse causes the amplitude of oscillator 3 to temporarily reach the ‘1’ state, however, it does not latch to this state. After an equilibration period, all oscillators settle back into the ‘0’ state. Similar error correcting dynamics are seen when the oscillators are initialised in the ’1’ states (see Supplementary Information).

Next, we repeat these simulations varying the drive frequency, drive amplitude and time of impulse. We find the behaviour of the coupled system can be categorized into four distinct phases (see Fig. 2c). When the drive is strong and near resonance, all oscillators evolve into their ‘1’ states. Conversely, when the oscillators are provided with weak drives, or are driven far away from resonance, they always evolve into their ‘0’ states. We term these two regions ‘1’ bias and ‘0’ bias, respectively. In between the two bias regions, the oscillators can exhibit bistability and can be initialized in either their collective ‘1’ or ‘0’ states, depending on the history of the applied forcing. We call this the initialise region. It should be noted that operating in this region does not guarantee error correction. We find that, for some parameters and impulse timings, it is possible for a single impulse to cause the system to transition between collective states. However, there remains a subspace that is guaranteed to correct all single impulses, regardless of when the impulse occurs. This region is labelled error correction in Fig. 2c (refer to the Supplementary Information for additional details).

For sufficiently high coupling rates, the error correction region can be made to be large, enabling stable operation. For instance, Fig. 2c was generated with a coupling rate equal to twice the intrinsic dissipation (i.e. \(\beta /\omega _0=2\Gamma \)). Here, near the centre of the error correction region, error correction is maintained even with large deviations in drive force. For instance, at \(\omega /\omega _0 = 1.152\), error correction is predicted to occur for drive forces in the range \(4.3 F_{crit} \le F \le 6.8 F_{crit}\). The size of the error correction region decreases with decreasing coupling rate, eventually disappearing altogether in the weak-coupling regime where \(\beta /\omega _0 <\Gamma \). The chosen numerical parameters are experimentally achievable, and based on previous demonstrations using silicon nitride nanomechanical oscillators on a silicon chip7. These oscillators can be made with a low intrinsic dissipation rate \(\Gamma \), such that the condition \(\beta /\omega _0 = 2 \Gamma \) can readily be achieved with acoustic tunnel junctions joining the oscillators38. A similar parameter regime can also be achieved with silicon nitride strings39,40, where string resonators can be strongly coupled to each other via coupling beams41. In practice, operating devices too close to the ‘0 bias’ region boundary is likely to give rise to instabilities, especially when environmental factors are considered (temperature change, charge build up, etc.). Experimentally, we anticipate that utilising a temperature control system and operating well within the error correction region will improve the stability of device performance.

The error correction of all single impulses can be further understood by considering the instantaneous energy of the system as a function of time. Figure 3a shows that the energy of the perturbed oscillator (purple line) increases rapidly due to the impulse, as expected. The two unperturbed oscillators then extract the excess energy and dissipate it to the environment, bringing the perturbed oscillator back into its original state. As the impulse amplitude is increased, the ability of the unperturbed oscillators to dissipate the excess energy is reduced, causing failures in error correction. This is shown in Fig. 3b where impulses that cause the system momentum to exceed \(p> 1.42 p_{\text {max,`1'}}\) result in failures of error correction (where \(p_{\text {max,`1'}}\) is the maximum momentum of the equilibrated ‘1’ state).

Single event upset on a 3-bit majority system. (a) Instantaneous energy of coupled system. Oscillators 1 and 2 are represented by the yellow trajectory and oscillator 3 is represented by the purple trajectory. The phase of the impulse relative to motion of the oscillator is indicated by the diagram on the top right corner of the figure. Since the amplitude of oscillator 3 is momentarily increased, its resonance frequency is up-shifted and it decouples from the other oscillators. The energy required for this to occur is indicated by a horizontal dashed line, and the region of decoupling is represented by grey shading. (b) Probability of error-correction failure (i.e. error occurs from impulse) with increasing amplitude of impulse. The horizontal axis is normalised to the maximum momentum of the oscillator when in the ‘1’ state. Inset: probability of error-correction failure for a larger range of impulse amplitudes. Grey region is the range of the main figure. Note that at high impulse amplitudes (i.e. \(\Delta p/p_{\text {max,`1'}} > 8.5 \)) the error-correction is always successful.

Unexpectedly, we find that the system also exhibits error correction of extremely large impulses (i.e. impulse energy large enough to transition all oscillators into the error state). This occurs due to an effect we call dynamic decoupling. An extremely large impulse will temporarily increase the amplitude of the perturbed oscillator, nonlinearly shifting its oscillation frequency away from the remaining oscillators. This decouples the perturbed oscillator from the others and precludes efficient energy exchange between them. The perturbed oscillator then dissipates the excess energy to the environment before reducing its amplitude and re-establishing coupling. The dashed line in Fig 3a indicates the approximate energy threshold above which dynamic decoupling starts to occur, defined as the point when the Duffing induced frequency shift exceeds the coupling rate between oscillators \(~\beta /\omega _0\) (See Supplemental Information). Indeed, dynamic decoupling becomes more pronounced for larger impulse amplitudes. As a result, for our set of parameters, there are two regimes that allow perfect error correction of SEUs; impulse amplitudes in the range \(0<\Delta p/p_{\text {max,`1'}}<1.42\) and those with \(\Delta p/p_{\text {max,`1'}}>8.5\). This is shown in Fig. 3b where the failure probability is zero for both small (main figure) and large (inset) impulse amplitudes. We note that the failure probability shows periodic behaviour within the range \(1.42< \Delta p/p_{\text {max,`1'}} < 8.5\). The origins of this periodicity remain a subject of further research.

The error correction protocol can perfectly correct single impulses, but we expect it to be susceptible to multiple simultaneous impulses. To explore this, we run simulations in which each oscillator has a fixed probability, \(P_{kick}\), of experiencing an impulse, i.e. a momentum kick, at a given time. Consequently, there is a finite probability of two or all three oscillators experiencing impulses simultaneously. We define an event as the occurrence of one or more impulses. If an event occurs and causes an error, then it is recorded and the simulation is reinitialised (see Supplementary Information for details). This allows one to determine the probability of failure for a given event probability. When this process is repeated for a range of event probabilities, the probability of failure (normalised by the event probability itself) is obtained.

We compare to equivalent simulations on a single oscillator (red in Fig. 4). The probability of failure per event for the single oscillator is constant at approximately 91%. The \(9 \%\) success rate can be attributed to a portion of impulses opposing the momentum of the oscillator and therefore having a reduced effect.

Simulated probability of system failure per event as a function of event probability per time interval. Red and blue dots represent the simulation results of single and coupled systems, respectively. Red and blue dashed lines represent the predicted model for single oscillator and majority vote of three independent oscillators, respectively. Red and blue solid lines represent the corrected model for single oscillator and coupled oscillators, respectively. Simulation parameters are the same as in Fig. 2.

The performance of the system was investigated with respect to an ideal majority voting scheme. Three way majority voting logic should correct all single impulses, but fail if two or more oscillators experience them. One can predict the theoretical failure rate, so defined, from a Binomial distribution for a given impulse probability (see Supplementary Information). When comparing the three oscillator system (blue dots) to the theoretical performance of a conventional majority voting scheme (blue dashed line), Fig. 4 shows that the coupled system surprisingly exhibits superior error-correcting performance.

Interestingly, the coupled system corrects all single impulses and 65% of the double impulses. We believe that the ability of the coupled oscillators to correct a double impulse is related to non-trivial transients of the system. Quite generally, as the oscillator transitions between its two stable states, it must re-phase its oscillation with respect to the external drive. In this situation, the displacement from an impulse may not have the correct phase to enable latching onto the stable state, causing the impulse energy to be extracted from the system through dissipation and the external drive. In some sense, the state of each oscillator is encoded twice in the dynamics, once in its amplitude and again in its phase. This creates additional redundancy of the logical bit, enabling double errors to be corrected.

In the modelling presented in this work, we have assumed the three oscillators in our design (see Fig. 2a) share identical physical parameters. However, in practice, minor fabrication differences can give rise to parameter mismatches in our devices and potentially impact error correction performance. To preserve performance, the oscillator resonant frequencies can be actively tuned to correct for any mismatch1,42, and the coupling between oscillators can be tightly controlled through design and engineering38. Furthermore, we have found that mismatches in oscillator dissipations (\(\Gamma \)) do not adversely affect the error correction region (refer to Supplementary Information for details). As a result, we anticipate the proposed design to be experimentally achievable.

Conclusion

In this work, we have explored the emergence of an error correcting phase in systems of coupled nonlinear oscillators. Using numerical simulations, we identify four distinct regions of behaviour in parameter space. We show that one of these regions enables autonomous error-correction from randomly occurring impulses, removing the need for additional logic operations to perform a majority-vote. Interestingly, error-correction is greatly enhanced for large impulses due to a dynamic decoupling of the perturbed oscillator, enabling error correction for impulses that are over ten times larger than the momentum of the ‘1’ state. Furthermore, the system is capable of correcting two simultaneous errors 65% of the time due to transient effects that de-phase the oscillators with respect to the drive. Our work shows that simple, small systems of coupled nonlinear oscillators with experimentally achievable parameters can be harnessed to enable autonomous error correction in nanomechanical computing architectures.

This work could be implemented in architectures where controllable strong resonator to resonator coupling has been demonstrated, such as silicon nitride membranes coupled via tunnel junctions38 or coupled nitride strings41. Another path forwards could be through exploring alternative coupling geometries within larger networks of oscillators to correct for a greater proportion of simultaneous errors. For example, ring-like networks of oscillators have been shown to exhibit exotic states of synchronization43, with applications in system stability, resilience and error correction. We envision that future work could integrate different coupling architectures and network sizes to enhance majority voting efficacy.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional simulation files and scripts are accessible upon request from W.P.B.

References

Schmid, S., Villanueva, L. G. & Roukes, M. L. Fundamentals of Nanomechanical Resonators 2nd edn. (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Roukes, M. Mechanical compution, redux? [nanoelectromechanical systems]. IEDM Tech. Digest. IEEE Int. Electron. Devices Meet. 2004, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2004.1419213 (2004).

Chaste, J. et al. A nanomechanical mass sensor with yoctogram resolution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2012.42 (2012).

Gavartin, E., Verlot, P. & Kippenberg, T. J. Stabilization of a linear nanomechanical oscillator to its thermodynamic limit. Nat. Commun. 4, 2860–2860. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3860 (2013).

Hanay, M. S. et al. Single-protein nanomechanical mass spectrometry in real time. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2012.119 (2012).

Yasuda, H. et al. Mechanical computing. Nature 598, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03623-y (2021).

Romero, E. et al. Acoustically driven single-frequency mechanical logic. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 054029. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.21.054029 (2024).

Wenzler, J.-S., Dunn, T., Toffoli, T. & Mohanty, P. A nanomechanical fredkin gate. Nano Lett. 14, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl403268b (2014).

Yamaguchi, H., Nishiguchi, K., Flurin, E., Fujiwara, A. & Mahboob, I. Interconnect-free parallel logic circuits in a single mechanical resonator. Nat. Commun. 2, 198–198. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1201 (2011).

Ilyas, S., Ahmed, S., Hafiz, M. A. A., Fariborzi, H. & Younis, M. I. Cascadable microelectromechanical resonator logic gate. J. Micromech. Microeng. 29, 015007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6439/aaf0e6 (2018).

Hatanaka, D., Darras, T., Mahboob, I., Onomitsu, K. & Yamaguchi, H. Broadband reconfigurable logic gates in phonon waveguides. Sci. Rep. 7, 12745–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12654-3 (2017).

Guerra, D. N. et al. A noise-assisted reprogrammable nanomechanical logic gate. Nano Lett. 10, 1168–1171 (2010).

Song, Y. et al. Additively manufacturable micro-mechanical logic gates. Nat. Commun. 10, 882–882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08678-0 (2019).

Tadokoro, Y. & Tanaka, H. Highly sensitive implementation of logic gates with a nonlinear nanomechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 024058. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.024058 (2021).

Roukes, M. L. & Karabalin, R. 10 nonlinear nanoelectromechanical systems. In Fluctuating Nonlinear Oscillators (eds Roukes, M. L. & Karabalin, R.) (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Coulombe, J. C., York, M. C. A. & Sylvestre, J. Computing with networks of nonlinear mechanical oscillators. PLoS One 12, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178663 (2017).

Yao, A. & Hikihara, T. Logic-memory device of a mechanical resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 123104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4896272 (2014).

Lee, Y.-B. et al. Sub-10 fj/bit radiation-hard nanoelectromechanical non-volatile memory. Nat. Commun. 14, 460. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36076-0 (2023).

Schroeder, B., Pinheiro, E. & Weber, W.-D. Dram errors in the wild: A large-scale field study. ACM SIGMETRICS Perform. Eval. Rev. 37, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1145/2492101.1555372 (2009).

Karnik, T. & Hazucha, P. Characterization of soft errors caused by single event upsets in cmos processes. IEEE Trans. Depend. Secure 1, 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2004.14 (2004).

Ziegler, J. F. & Lanford, W. A. Effect of cosmic rays on computer memories. Science 206, 776–788. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.206.4420.776 (1979).

She, X. & McElvain, K. Time multiplexed triple modular redundancy for single event upset mitigation. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 56, 2443–2448. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2009.2021656 (2009).

Restrepo, J. G., Ott, E. & Hunt, B. R. Onset of synchronization in large networks of coupled oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 71, 036151. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.71.036151 (2005).

Vaidya, J., Bashar, M. K. & Shukla, N. Using noise to augment synchronization among oscillators. Sci. Rep. 11, 4462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83806-9 (2021).

Teramae, J. & Tanaka, D. Robustness of the noise-induced phase synchronization in a general class of limit cycle oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 204103. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.204103 (2004).

Kelly, F., Maulloo, A. & Tan, D. Rate control for communication networks: Shadow prices, proportional fairness and stability. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 49, 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600523 (1998).

Barabási, A.-L., Jeong, H. & Albert, R. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 406, 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1038/35019019 (2000).

Ganesan, A., Do, C. & Seshia, A. Phononic frequency comb via intrinsic three-wave mixing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 033903. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.033903 (2017).

Pietras, B. & Daffertshofer, A. Network dynamics of coupled oscillators and phase reduction techniques. Phys. Rep. 819, 1–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2019.06.001 (2019).

Rakshit, S., Bera, B. K., Majhi, S., Hens, C. & Ghosh, D. Basin stability measure of different steady states in coupled oscillators. Sci. Rep. 7, 45909–45909. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45909 (2017).

Kim, H., Lee, S. H., Davidsen, J. & Son, S.-W. Multistability and variations in basin of attraction in power-grid systems. New J. Phys. 20, 113006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/aae8eb (2018).

Serletis, A., Shahmoradi, A. & Serletis, D. Effect of noise on the bifurcation behavior of nonlinear dynamical systems. Chaos Soliton Fractal 33, 914–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.01.046 (2007).

Baesens, C., Guckenheimer, J., Kim, S. & MacKay, R. Three coupled oscillators: Mode-locking, global bifurcations and toroidal chaos. Physica D 49, 387–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(91)90155-3 (1991).

Bag, B. C., Petrosyan, K. G. & Hu, C.-K. Influence of noise on the synchronization of the stochastic Kuramoto model. Phys. Rev. E 76, 056210. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.76.056210 (2007).

Dutta, S. et al. Programmable coupled oscillators for synchronized locomotion. Nat. Commun. 10, 3299–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11198-6 (2019).

Boaknin, E. et al. Dispersive microwave bifurcation of a superconducting resonator cavity incorporating a Josephson junction. http://arxiv.org/abs/org. urlhttps://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.0702445

Moss, D. J. & Eggleton, B. J. Toward Photonic Integrated Circuit All-Optical Signal Processing Based on Kerr Nonlinearities Vol. 6 (SPIE, 2008).

Mauranyapin, N. P. et al. Tunneling of transverse acoustic waves on a silicon chip. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 054036. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.054036 (2021).

Schmid, S., Jensen, K. D., Nielsen, K. H. & Boisen, A. Damping mechanisms in high-\(q\) micro and nanomechanical string resonators. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165307. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.165307 (2011).

Schilling, R. et al. Mode shape engineering of silicon nitride nano-strings for quantum optomechanics. In 2017 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), 1–2 (2017).

Gajo, K., Schüz, S. & Weig, E. M. Strong 4-mode coupling of nanomechanical string resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 133109. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4995230 (2017).

Kozinsky, I., Postma, H. W. C., Bargatin, I. & Roukes, M. L. Tuning nonlinearity, dynamic range, and frequency of nanomechanical resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 253101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2209211 (2006).

Matheny, M. H. et al. Exotic states in a simple network of nanoelectromechanical oscillators. Science 363, eaav7932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav7932 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was primarily funded by the Australian Research Council and Lockheed Martin Corporation through the Australian Research Council Linkage Grant No. LP190101159. Support was also provided by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Engineered Quantum Systems (No. CE170100009). G.I.H. and C.G.B. acknowledge their Australian Research Council grants (No. DE210100848 and No. DE190100318), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. J: Conceptualisation, numerical simulation, methodology, analysis. C. G. B: Conceptualisation, methodology, analysis. E. R: Methodology, analysis. T.M.F.H: Methodology, analysis. W. P. B: Conceptualisation, methodology, analysis. G.I.H: Conceptualisation, numerical simulation, methodology, analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, X., Baker, C.G., Romero, E. et al. Engineering error correcting dynamics in nanomechanical systems. Sci Rep 14, 20431 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71679-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71679-7