Abstract

In mammals, NMDA receptor antagonists have been linked to the emergence of high-frequency oscillations (HFO, 130–180 Hz) in cortical and subcortical brain regions. The extent to which transmission of this rhythm is dependent on feedforward (bottom-up) or feedback (top-down) mechanisms is unclear. Previously, we have shown that the olfactory bulb (OB), known to orchestrate oscillations in many brain regions, is an important node in the NMDA receptor-dependent HFO network. Since the piriform cortex (PC) receives major input from the OB, and can modulate OB activity via feedback projections, it represents an ideal site to investigate transmission modalities. Here we show, using silicon probes, that NMDA receptor antagonist HFO are present in the PC associated with current dipoles, although of lower power than the OB. Granger causality and peak-lag analyses implicated the OB as the driver of HFO in the PC. Consistent with this, reversible inhibition of the OB resulted in a reduction of HFO power both locally and in the PC. In contrast, inhibition of the PC had minimal impact on OB activity. Collectively, these findings point to bottom-up mechanisms in mediating the transmission of NMDA receptor antagonist-HFO, at least in olfactory circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subanesthetic doses of N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonists, such as ketamine have been used for decades to model psychosis1,2. Over the past two decades, ketamine has been found effective for the treatment of depression, bipolar disorder, and suicidal ideation3,4. Despite these clinical advances the fundamental brain networks affected by NMDAR antagonists are still only understood in part.

Local field potential (LFP) oscillations are readily observable in the brain across a wide range of frequency bands. Fast oscillations are considered to temporally bind information across different areas5,6, and may subserve a variety of functions, including cognitive functions such as memory, attention7, and consciousness. Clinical and preclinical findings have shown changes in gamma oscillations after administration of ketamine8,9,10. However, frequencies above the classical “gamma” band have been less widely investigated. Preclinical studies using experimental rodents have shown reliably that subanesthetic doses of NMDAR antagonists, including ketamine, produce coherent high-frequency oscillations (HFO) in corticolimbic brain regions11,12. Recent electrocorticographic recordings show that ketamine can also increase the power of HFO monkeys13 and cats14, and in electroencephalography of humans15. As such, the ketamine-HFO rhythm may be a fundamental brain rhythm and preclinical studies represent a translatable valid way to probe this activity.

In rodents, the olfactory bulb (OB) has been identified as a physiological source of HFO associated with NMDAR antagonist injection16 and appears to be an integral node in the generation of this rhythm since reversible inactivation of the OB can suppress ketamine-HFO both locally and in the ventral striatum16. The piriform cortex (PC) is the main target of excitatory OB projections, which in turn sends excitatory projections to widespread corticolimbic regions17. The PC also projects back to the granule cells of the OB18 and can impact its circuits by controlling the “gain” of the rhythms generated there19,20. Further, recent work has shown that changes in oscillatory activity in OB-PC networks have been linked to depression-like behaviors in rodents, which can be restored by ketamine21. Indicating olfactory networks may be a functionally-relevant target for NMDAR antagonists. Whether HFO associated with NMDAR blockade can be recorded from the PC, and to what extent OB/PC bidirectional communication influences HFO rhythmogenesis is unknown.

To address this issue, we mapped HFO across PC areas and found this rhythm predominated in the anterior PC under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. We corroborated our findings using awake rats and compared NMDAR antagonist-enhanced HFO in OB and anterior PC, we then investigated if reversible inhibition of one structure affected LFP oscillations in the other. We conclude that NMDAR antagonist HFO can be transmitted via bottom-up processing.

Results

Neuroanatomical distribution of HFO in the PC in ketamine-xylazine anesthetized rats

The PC is divided into anterior and posterior regions, with anterior regions receiving greater input from the OB22. We first targeted the PC and olfactory tubercle (OT) using either 3.2 mm or 0.68 mm 32-channel silicon probes coupled with DiI staining to mark electrode positions; histology obtained in this manner can be processed straightforwardly with minimal dye dispersion. These experiments were carried out under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia where a slower 80–130 Hz rhythm corresponding to HFO in awake rats can be recorded14. Analyses of power revealed a significant effect of structure (one-way ANOVA p = 0.0004, F(2,21) = 11.41, p < 0.001 for both). Bonferroni post hoc revealed that HFO power was larger in the aPC, compared to the pPC and OT (p < 0.01 for both, Fig. 1A). The power of HFO tended to be larger for electrode contacts close to the lateral olfactory tract.

HFO in the rat piriform cortex under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. (A) Power of HFO (80–130 Hz) recorded from the anterior (aPC, N = 13) and posterior area of the PC (pPC, N = 5) and olfactory tubercle (OT, N = 6) (one-way ANOVA p = 0.0004, F(2,21) = 11.41, p < 0.001 for both). Bonferroni post hoc revealed that HFO power was larger in the aPC, compared to the pPC and OT (p < 0.01 for both). (B) Tracks of 32-channel probes (3.2 mm, intercontact distance 100 µm) from different rats are superimposed on the same coronal section of the aPC and depth-profile of 80–130 Hz oscillations showing how phase changes about the pyramidal layer, each line represents a different rat (N = 7 rats). Note one implantation (red line) did not reach the aPC. (C) same as B only for 32 channels silicon probes with a contact distance of 20 µm, N = 5 rats. Note one implantation (red line) was in layers 1 and 2 of the aPC. (D) An example image showing the electrode tip (yellow) for a 0.68 mm silicon probe crossing the aPC. (E) Corresponding 80–130 Hz band-pass filtered signal. F, Current source density analysis from an 8 × 8 grid electrode recorded from the aPC. Note the dipole follows the profile of the aPC.

Given the relatively larger power of HFO in the aPC, and its greater OB innervation22 we focused our analyses on this subregion. Electrode track locations for 3.2 mm silicon probes implanted in the aPC and the corresponding depth-profile phase data are shown in Fig. 1B (3.2 mm length, N = 7 rats). We observed phase reversal close to the piriform cortex. One implantation (shown in red) did not reach the piriform cortex and was not associated with phase reversal. We examined the changes in the aPC in further detail using 0.68 mm electrodes in five rats (Fig. 1C). Within the PC changes in phase tended to occur at the border of layer 2/3. One rat was implanted below layer 3 and was not associated with a phase shift (shown in red). Images offering a broader anatomical context can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1 online. An example showing phase reversal of the 80–130 Hz band-pass filtered signal from a 0.68 mm electrode is shown in 1D and E. Next, we carried out more detailed LFP studies of the aPC using an 8 × 8 grid array in 5 rats. Of these, the aPC was successfully reached in 4 out of 5 rats (one implantation was dorsal). CSD analyses revealed current dipoles close to the pyramidal layer in those that reached the aPC (Fig. 1F, and Supplementary Fig. S2 online).

Coherent HFO in the OB and aPC after NMDAR receptor blockade in freely moving rats

Having shown that the aPC is a good candidate for NMDAR antagonist-HFO we next carried out recordings in awake rats chronically implanted with electrodes in the OB and aPC (for information on tracks after electrodes, please refer to Supplementary Fig. S3 online). Here, we report the results of LFP oscillations recorded simultaneously in the OB and aPC of sixteen freely moving rats. Figure 2A shows the typical pattern of LFP recordings from the OB and aPC after 0.15 mg/kg MK801 (i.p.). In awake rats, spontaneous HFO (130–180 Hz) are present as a small bump in the power spectra of LFPs recorded from the OB, but largely absent in the aPC. Notably, changes in field potential oscillatory activity after systemic injection of MK801 primarily affected the HFO band without marked changes in other frequency bands (Fig. 2B). LFP oscillations recorded in monopolar field potentials are not always generated at the recording site but can propagate passively from remote areas23. This is also the case for NMDAR antagonist-HFO24]. One way to address this issue is to examine the bipolar signal which removes in-phase volume conducted activity arising outside of the recording sites. To address this, we derived the bipolar signal from two monopolar recordings (interelectrode distance up to 1 mm). Analysis of the derived-bipolar signal confirmed that MK801 significantly increased the power of HFO in both the OB and aPC (inserts in Fig. 2B). Data showing HFO power, in simultaneous monopolar LFP from the OB and aPC, approximately 30 min after MK801 injection are shown in Fig. 2C (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, p = 0.0009). Analysis of the relationship between changes in HFO power in the OB and aPC after MK801 injection revealed a positive correlation (p < 0.05) in 15 of 16 rats (Fig. 2D, this analysis was conducted on changes in HFO power in the OB and aPC specifically during the post-MK801 time period, scatter shows all individual rats). Coherence measures the phase relationship and strength of coordination between oscillations recorded from different sources. In the context of analyzing brain rhythms, it can be used as an index of functional connectivity. We observed strong coherence at the HFO band in the OB and aPC after injection of MK801 which was relatively weak at baseline. Figure 2E shows the mean coherence spectra at baseline and after MK801. Coherence values for individual rats for the 130–180 Hz band are also shown at baseline and after MK801 (p < 0.001, paired t-test).

Coherent NMDAR antagonist HFO in the OB and aPC after MK801 injection in freely moving rats. (A) Examples of 130–180 Hz band-pass filtered signals and the corresponding raw LFPs recorded simultaneously from the OB and aPC after 0.15 mg/kg MK801 (please note the same scale for all signals). (B) Mean power spectra (N = 16 rats) of monopolar LFPs recorded from the OB and aPC analyzed for 60 s at baseline (BL) and 29–30 min post systemic injection of MK801. Insert, shows the bipolar-derived signal for the same data. (C) Comparison of HFO power in the OB and aPC post systemic injection of MK801, p = 0.0009, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. (D) Group mean values of HFO in the OB and aPC post MK801 showing a positive correlation and Spearman rank values for the individual rats. Averages were computed from 60 windows (30 seconds each) totaling 1800 seconds (30 minutes) post MK801 i.p. (E) Coherence spectra calculated at baseline and post MK801. The adjacent plot shows the maximum coherence for the 130–180 Hz band at baseline and after MK801 for each rat (p < 0.001, paired t-test). F1, Representative comodulograms post MK801 showing slow oscillations (1–10 Hz) can modulate the 130–180 Hz band recorded locally in the OB and PC. The third example shows slow oscillations in the OB (1–10 Hz) can modulate 130–180 Hz band in the PC. F2, Modulation indices for individual rats at baseline and post MK801, p < 0.0001 for the OB), p = 0.004 for the PC, p = 0.0002 for the OB-PC (paired t-tests).

Consistent with others, we observed slow oscillatory respiration rhythms (1–10 Hz), visible in the raw LFP which were similar in the OB and PC21,25,26. Fast oscillations in olfactory regions are known to be modulated by much slower rhythms (1–10 Hz). In the mammalian OB, these oscillations are usually in the band 1–10 Hz and are typically associated with nasal respiration rhythm27,28,29,30. We found that HFO, after NMDAR blockade, was modulated by slower oscillations recorded locally in the OB and aPC (see autocomodulograms of OB and aPC activity, Fig. 2F1). This is consistent with findings from other brain regions including cortical and basal ganglia regions31,32,33,34,35. We next examined if slow oscillations recorded in the OB could modulate HFO recorded in the aPC. We found cross-frequency coupling of the MK801-enhanced HFO to 1–10 Hz oscillations both locally, in the OB and aPC (p < 0.0001 for the OB, p = 0.004 for the aPC, paired t-tests) . We also found HFO in the aPC was modulated by slow oscillations recorded in the OB (p = 0.0002 for the OB-PC, paired t-test, Fig. 2F2). Additionally, the visualization of the comodulograms for the baseline condition in the OB and aPC is available in Supplementary Fig. S4 online.

Relationship between HFO in the OB and aPC

We examined functional connectivity between the OB and aPC using Granger causality (GC). We observed strong directionality for the HFO band in the OB-aPC direction. This was significant when comparing baseline values to post MK801 (p < 0.0001, paired t-test, Fig. 3A). We also observed small but significant increases in the aPC-OB direction (p = 0.0003, paired t-test, Fig. 3B). Of note, a distinct spectral peak representing the low-gamma (40–60 Hz) band was visible in the aPC-OB direction.

Ipsilateral transmission of NMDAR antagonist HFO in the OB to the aPC. (A,B) Mean Granger plots before and after injection of MK801 for the OB > aPC and aPC > OB directions. Adjacent plots show the values for the 130–180 Hz band at baseline (BL) and post MK801 (paired t-test, OB > PC, p < 0.0001; PC > OB, p = 0.0003) (N = 16 rats). Plots showing peak Granger values for the 130–180 Hz band at baseline and after injection of MK801 for individual rats. (C,D) Example amplitude plots showing HFO the relationship between HFO in the OB and PC from the ipsilateral and contralateral sides. Each row represents a separate sweep of HFO when triggered on the OB from the ipsilateral or contralateral side. Note HFO between the OB and PC is remarkably stable when triggered on the ipsilateral OB, but disorganized when triggered on HFO from the contralateral OB. (E) Mean power of HFO from the ipsilateral or contralateral OB (unpaired t-test, p = 0.1646), and mean power of HFO from the aPC when triggered on OB HFO from either side (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0011). The bottom panel shows two plots: the left plot (F) shows the averaged z-scored HFO envelopes recorded from the OB and PC across 13 LFP recordings from the same hemisphere (ipsilateral), and the right plot (G) shows the time delay between the OB and PC envelope peaks, demonstrating that in most cases the PC envelope peak occurs later than the OB envelope peak (PC lagged behind the OB by 1.1 + 0.6 ms, mean + SD).

Given that the main OB projects ipsilaterally to the PC we predicted the relationship between HFO in the OB/PC on ipsilateral and contralateral sides would be different. We analyzed the 130–180 Hz band-pass filtered signal in simultaneously recorded LFPs from the OB (both sides) and aPC (one side). Bursts of HFO recorded from the left and right sides of the OB were marked by single events. In all rats (N = 16) we observed HFO in the aPC were organized when triggered on HFO events from the OB of the ipsilateral side (Fig. 3C), but became disorganized when triggered on HFO events from the contralateral OB (Fig. 3D). Analyses of group effects (Fig. 3E) showed no difference in the amplitude of HFO recorded from the ipsilateral or contralateral OB (p = 0.1646, unpaired t-test), but HFO amplitude was markedly reduced in the aPC when triggered on the contralateral OB (p = 0.0011, unpaired t-test). We next examined the temporal relationship between HFO in the OB and aPC on the ipsilateral sides by calculating the RMS of the 130–180 Hz envelope. This visualization aims to highlight the temporal dynamics in the two brain regions after normalizing the data. The z-scoring ensures that both OB and aPC signals are on the same scale, meaning that the observed differences in their envelopes are not due to differences in absolute amplitudes, but rather to differences in relative dynamics. Figure 3F shows average bursts of HFO in the OB and aPC and their corresponding envelopes from a single rat. We found bursts of HFO in the OB and aPC were coherent in 13 of 16 rats. In three rats bursts of HFO in the OB and aPC were not coherent, in those rats nasal respiration rhythm in the OB was phase reversed and HFO bursts although present but had different temporal dynamics between the structures (see Supplementary Fig. S5 online for examples). The mean HFO envelope from the OB and aPC of 13 rats where HFO is shown in Fig. 3G. The associated scatter plot shows consistent time delays, and indicates a lead-lag relationship. In most cases, the aPC peak occurs shortly after the OB peak (aPC lagged behind the OB by 1.1 + 0.6 ms, mean + SD). The time lags vary in a few recordings displaying near-zero or even slightly negative values, indicating that in some cases, the aPC peak occurred almost simultaneously or slightly before the OB peak.

Reversible inhibition of the OB reduces the power of HFO locally and in the aPC in freely moving rats

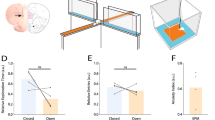

Given that classical gamma in the PC can be driven by input arising from the OB21,26, and that our analyses suggested that the OB was driving HFO in the aPC, we hypothesized that inactivation of the OB would reduce HFO power in the aPC. This was tested using a pharmacological approach by infusing the GABA-A receptor agonist, muscimol, which produces reversible inhibition (N = 8). The OB is neuroanatomically confined and we used a low volume (0.5 µl per side) of infusion to limit possible spread. Muscimol infusion to the OB produced an almost immediate reduction in the power of MK801-enhanced HFO locally in the OB and in the aPC. By contrast, saline infusion had no obvious effect. Spectrograms from a representative rat and complete time-courses are shown in Fig. 4A,B. Comparison of HFO power 5–10 min post-infusion, for muscimol versus saline, revealed a significant reduction (p = 0.0078, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, both for the OB and aPC) that was consistent for all rats. Reductions in HFO power, in the OB correlated with changes in the aPC.

Reversible inhibition of the OB reduces NMDAR antagonist-enhanced HFO power in the aPC. (A,B) Microinfusion of muscimol to the OB reduces MK801-enhanced HFO power (130-180 Hz) in both the OB and aPC. Spectrograms and time courses show a reduction in HFO power after OB microinfusion of the GABA-A receptor agonist muscimol in the OB and aPC (N = 8). Microinfusion of muscimol and saline is indicated by an arrow. Before-after plots present HFO power for individual rats 5–10 min after OB musicmol infusion (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, p = 0.0078 for both). (C) Examples of rats locomotor activity (beam breaks) after OB saline or muscimol infusion. (D) Bar chart representing a comparison of total beam breaks 30 min post saline or muscimol infusion (paired t-test, p = 0.5869).

Some previous studies12,31 but not all36 have shown that the power of HFO correlates with beam breaks. Given that HFO were absent from the OB and aPC (after muscimol infusion) we were interested to examine whether there were obvious changes in locomotor activity. Analysis of beam break activity (Fig. 4C) revealed no differences in MK801-enhanced locomotor activity which was similar (paired t-test, p = 0.5869) for both muscimol and saline-infused controls (Fig. 4D).

Reversible inhibition of the aPC does not affect HFO power in the OB in freely moving rats

The PC is one of the major recipients of OB efferents and sends reciprocal excitatory projections back to inhibitory granule cells of the OB where they can modulate the activity of mitral/tufted cells19,37. In this way, the PC is considered to serve as a gain control for OB activity. To examine the effect of cortical feedback to the OB, we reversibly inhibited aPC using muscimol (N = 10) or TTX (N = 6). We found muscimol 5–10 min. post-infusion to the aPC did not significantly affect the power of MK801-enhanced HFO within the aPC (p = 0.1055, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test), nor did it affect HFO power in the OB (p = 0.2754, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). Taken as a whole there were no group differences however, as shown in the individual rats there was a large spread of data. Spectrograms from a representative rat and complete time-courses are shown in Fig. 5A,B. Towards the end of the experiment there was a small reduction in HFO power in the aPC which reached significance at 25 min. (p = 0.0098, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test).

Reversible inhibition of the aPC does not reduce HFO power in the OB. (A,B) Spectrogram and time courses showing HFO power in the OB and aPC (N = 10). Microinfusion of muscimol and saline is indicated by an arrow. Plots present HFO power for individual rats 5–10 min after muscimol or saline infusion to the aPC (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, p = 0.1055 for the OB, p = 0.2754 for the aPC). (C,D) Microinfusion of 10 ng/μl TTX to the aPC reduces MK801-enhanced HFO power (130–180 Hz) locally but not in the OB (N = 6). Spectrogram and time courses show HFO power after aPC microinfusion of the sodium channel blocker TTX in the aPC and OB (N = 10). Plots present HFO power for individual rats 5–10 min after TTX or saline infusion to the aPC (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, p = 0.0313 for the OB, p = 0.0938 for the aPC).

Muscimol is a GABA-A receptor agonist which increases inhibition at the site of infusion. As such, local infusion of muscimol would be expected to primarily reduce PC output, without markedly affecting afferent input. Axons of mitral and tufted cells travel along the lateral olfactory tract to innervate the PC. Given the weak effect of muscimol infusion to the aPC we next examined the effect of the sodium channel blocker, TTX, which suppresses both input to the PC and its output by blocking action potential propagation. A subgroup received TTX infusion to the aPC. In contrast to muscimol, we observed an immediate reduction in MK801-enhanced HFO power in the aPC (p = 0.0313, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test) without affecting the power of HFO in the OB which remained high (p = 0.0938, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, Fig. 5C,D).

Discussion

Our experiments causally link activity in the OB with NMDAR antagonist-enhanced HFO in the PC. Although PC projections can directly influence activity in the OB, this input is not chiefly associated with the modulation of NMDAR antagonist HFO. Together our findings suggest bottom-up transmission of HFO, at least within olfactory networks.

The PC is a trilaminar paleocortex involved in olfactory processing. It receives direct input from mitral/tufted cells of the OB which travel along the olfactory tract and synapse with apical dendrites of pyramidal cells in layer 1 of the PC38. The PC projects back to granule cells of the OB, and in this way can modulate ongoing activity in the OB. We assessed the relative contribution of these regions in the generation of NMDAR antagonist-HFO using muscimol, a GABA-A receptor agonist that causes rapid and reversible suppression of neuronal activity by enhanced hyperpolarization. Muscimol infusion to the OB produced immediate and parallel reductions in HFO power in both the OB and aPC. In contrast, infusion to the aPC had relatively weak effects. As such, at least within the OB-PC circuit NMDAR antagonist-HFO reflects a bottom-up, rather than top-down, direction of information flow. These findings are also in line with studies showing higher frequencies, e.g. gamma, utilize bottom-up communication, whereas top-down communications tend to be associated with lower frequencies, e.g. theta and beta39. Bottom-up activity is usually “stimulus-driven” and in line with this nares blockade attenuates NMDAR antagonist-HFO35. Additionally, in ketamine-xylazine anesthetized rats NMDAR antagonist HFO were largely unaffected by surgical excision of large parts of the PC and surrounding structures14, in line with the findings reported here. The OB is known to receive direct top-down input from at least two other regions, the lateral entorhinal cortex and the anterior olfactory nucleus40 as well as neuromodulatory midbrain input. Our findings do not exclude the possibility that other regions may exert top-down modulation of NMDAR antagonist-HFO.

The feedforward-projecting neurons involved in the broadcast HFO from the OB arise from the mitral/EPL layer of the bulb. The axons of mitral/tufted (M/T) cells from these layers travel along the lateral olfactory tract and form symmetric synapses with the dendrites of PC pyramidal cells at layer 1. M/T cells differentially project to the PC, with M cells being PC-oriented and T cells olfactory tubercle-oriented41. Rhythmic spiking of M cells would be expected to produce transient shifts in the membrane potential of targets within the PC, reflecting the input it receives. As might be expected the power of HFO in the PC was coherent with OB activity and at least an order of magnitude smaller. Bursts of HFO in the OB and PC were coherent in most rats. This coherence indicates a strong coupling between the OB and the PC when the OB electrode is located to capture mitral layer activity. Activity in the OB peaked slightly before the PC envelope, which is consistent with previous analyses showing that OB activity tends to lead PC activity, particularly within the same hemisphere. This relationship indicates the OB's role in driving or influencing oscillatory activity in the PC, helping in the synchronization of processes within the hemisphere. In three rats, HFO bursts were still present in the OB and PC but exhibited different temporal dynamics. These were associated with reversal of nasal respiration rhythm phase in the OB channel and indicate that the precise location of the electrode within the OB can influence the observed relationship between OB and PC activity.

The OB differentially projects to anterior and posterior regions of the PC38,42. Spatially we observed an anterior–posterior gradient in HFO power which was stronger in the anterior PC, indicative of predominant HFO drive from the OB.

Although NMDAR antagonist-HFO can be recorded in the PC, is it actually generated at this site? This is a fundamental issue that permeates all LFP recordings. With respect to NMDAR antagonist-HFO, there are conflicting reports concerning whether the generation of NMDAR antagonist-HFO is restricted to a few specific regions, or is more widespread24,33,43,44. We showed previously that infusion of TTX to the PFC or caudate did not affect HFO power, suggesting HFO recorded in those regions was not locally generated24. Given that muscimol infusion to the aPC produced only weak effects, it could be argued that HFO was not generated in this region. To address this issue we infused TTX, which in contrast to muscimol, also inhibits passing fibers and axonal input to the infused area45. We found that TTX, but not muscimol, produced an immediate reduction in HFO power in the aPC. We interpreted this effect to be due to the additional effect TTX has on passing fibers, in particular affecting transmission at the presynaptic axon terminals of M/T cells to pyramidal cell dendrites in superficial layer 1 of the aPC. Muscimol infusion to the aPC would leave this synaptic activity largely intact, and as such NMDAR antagonist-HFO remained at high amplitude. Our findings from CSD analyses show that there is a dipole associated with HFOs in the aPC. There is modeling and in vivo evidence that dipoles recorded in extracellular potentials can be generated by action potentials. These can become prominent in areas of dense axonal branching46. Indeed, in our studies, CSD changes were more pronounced in anterior regions of the PC, closest to the lateral olfactory tract. Together we interpret these findings to mean that NMDAR antagonist-HFO in aPC is not generated by an intrinsic PC network (compared to OB) but arises, at least in part, through axonal input originating from the OB. Therefore, in contrast to the OB, HFO in the PC would have only a limited contribution to information processing within this region.

In summary, our study reveals that NMDAR antagonist-enhanced HFO can be transmitted in a bottom-up manner. Our findings suggest that while HFO are recorded in the PC, their primary generation occurs through axonal input from the OB rather than intrinsic PC networks. This highlights the significance of OB-driven activity in shaping activity within the PC, and likely other areas, providing valuable insights into how drugs, such as ketamine, can affect fundamental brain activity.

Methods

Acute experiments

Seventeen male Wistar rats (250–350 g) were initially anesthetized using isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Burr holes were drilled above specific coordinates: the OB (anteroposterior [AP] + 6.0–6.7 mm, mediolateral [ML] ± 0.5 mm, dorsoventral [DV] 3–3.5 mm), and additional holes were drilled over one or two other structures: anterior PC (AP + 0.5–2 mm, ML + 4–5 mm, DV 8.0 mm), posterior PC (AP -1–2 mm, ML 5–6 mm, DV 8.5 mm), or olfactory tubercle (OT, AP + 1–2 mm, ML + 1–2 mm, DV 8 mm). Isoflurane anesthesia was replaced by ketamine-xylazine anesthesia (ketamine 100 mg/kg + xylazine 10 mg/kg) as previously14. For each rat a silicon probe electrode was implanted in the OB (16-channel linear probe, A1 × 16-10 mm-100–177) as a reference structure since we have shown previously HFO occurs in the OB under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. We obtained recordings from the PC/OT using 32 channel probes recording from up to two structures per rat (A1 × 32-Edge-10 mm-20–177 or A1 × 32-10 mm-100–177, NeuroNexus, USA). Before recordings, the probes were dipped in a 5% solution of DiI (Sigma, Poland) dissolved in DMSO (Sigma, Poland). LFP data were acquired using a SmartBox (NeuroNexus, USA) and NeuroNexus proprietary software. When a second olfactory structure was recorded, the 32-channel probe was removed and recoated with DiI and inserted into a different olfactory structure. In a separate group of 5 rats an 8 × 8 “grid” (A8 × 8-10 mm-200–200–177) probe was aimed at the aPC and a 16-channel probe in the OB. At the end of the recordings rats were killed by an overdose of anesthesia and brain tissue was processed for histology.

Chronic experiments

Sixteen male Wistar rats (250–350 g) were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Rats (N = 8) were implanted with a pair of tungsten electrodes (125 μm, Science Products, Germany) and 22 gauge stainless steel guides (Bilaney, Germany) in the OB (AP + 6.7, ML ± 0.5, DV 3–3.5 mm) and unilaterally with an electrode in the aPC (AP + 0.5, ML + 4.5, DV 8.0 mm). Two of these rats had an additional guide in the aPC. A separate group of rats (N = 8) had electrodes implanted bilaterally in the OB and an electrode guide complex in the aPC. The guides and electrode complexes, along with the screws, were secured to the skull using dental cement, which formed a socket that stabilized the screws and electrodes. A screw posterior to the bregma (above the cerebellum) was used as a reference/ground in all cases. Ethics permission: All experiments were conducted in accordance with the European community guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (86/609/EEC) and approved by the 1st Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments in Warsaw, Poland (permission number 1159/2021). All experiments were conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Recording

One week after surgery, rats were placed in an arena (44 × 50 × 42 cm). LFPs were recorded through a JFET preamplifier, amplified 1000 × , filtered 0.1–1000 Hz (Model 1700 Differential AC amplifier, A-M Systems, USA), and digitized at 5 kHz (Micro1401, CED, Cambridge, UK). Horizontal locomotor activity was assessed by photocell beam breaks (Columbus Instruments, USA). Rats were recorded for 2 days prior to the main experiment to habituate them to the recording chamber. Occasional muscle artifacts were visible in the LFP recordings (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online).

Drug infusion

Briefly, 30 min post i.p injection of 0.15 mg/kg MK801 (Sigma, Poland) the animal was disconnected from the equipment and gently restrained to infuse the selected substance through the implanted cannulas using an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, USA). Stylets were removed from the guide and a 28 gauge infusion needle (Bilaney, Germany) was inserted and descended by hand 1 mm below the tip of the guide. Infusions were carried out at a rate of 0.5 µl/min. Muscimol (0.5 µg/0.5 µl, Sigma, Poland) or saline (0.5 µl) was infused to the OB (N = 8 rats) and aPC (N = 8 rats) groups. A subgroup of the aPC group (N = 6 rats) received TTX (10 ng/0.5 µl) post 0.15 mg/kg MK801.

Histology

At the end of the study rats were killed by an overdose of pentobarbital. Brains were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, Poland) and preserved using 30% sucrose (Sigma, Poland). For the acute experiments, using silicon probes under ketamine-xylazine, the electrode placements were determined based on the DiI track visualized using a fluorescent microscope in the bright-field and dark-field sections (20–30 µm). Electrolytic lesions were made for the chronically implanted rats and electrode locations were determined on 35 µm Cresyl violet (Sigma, UK) stained sections prepared using a cryostat.

Data analyses

LFP recordings stored in Spike2 format were imported into Python using the Spike2IO class from the Neo library. We converted raw LFP data from SMR to MNE-Python format. Data were filtered within the frequency range of 130 Hz to 180 Hz or 80 Hz to 130 Hz (for ketamine xylazine recordings) using a finite impulse response (FIR) MNE-filter with defined transition bandwidths of 2 for both high and low frequencies. Python was used to calculate power and phase analyses, current source density47,48 and coherence, comodulation, Granger causality and modulation indices for OB and aPC recordings. For full details see Supplementary Methods.

Statistics

All groups were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk’s test for normality. If the data was normally distributed we used a one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test or paired and unpaired Student t-test. If data were not normally distributed, we used the Wilcoxon test followed by post-hoc testing. In all cases, differences were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Luby, E. D., Cohen, B. D., Rosenbaum, G., Gottlieb, J. S. & Kelley, R. Study of a new schizophrenomimetic drug—sernyl. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 81, 363 (1959).

Krystal, K. L. et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive nmda antagonist, ketamine, in humans: Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51, 199–214 (1994).

Zarate, C. A. et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 856 (2006).

Zarate, C. A. et al. Replication of ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: A randomized controlled add-on trial. Biol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010 (2012).

König, P., Engel, A. K. & Singer, W. Relation between oscillatory activity and long-range synchronization in cat visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 92, 290–294 (1995).

Fries, P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: Neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 474–480 (2005).

Jensen, O., Kaiser, J. & Lachaux, J. P. Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.001 (2007).

Rivolta, D. et al. Ketamine dysregulates the amplitude and connectivity of high-frequency oscillations in cortical-subcortical networks in humans: Evidence from resting-state magnetoencephalography-recordings. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 1105–1114 (2015).

Pinault, D. N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists ketamine and MK-801 induce wake-related aberrant γ oscillations in the rat neocortex. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 730–735 (2008).

Hirano, Y. & Uhlhaas, P. J. Current findings and perspectives on aberrant neural oscillations in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13300 (2021).

Flores, F. J. et al. A PK-PD model of ketamine-induced high-frequency oscillations. J. Neural Eng. 12, 056006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2560/12/5/056006 (2015).

Hunt, M. J., Raynaud, B. & Garcia, R. Ketamine dose-dependently induces high-frequency oscillations in the nucleus accumbens in freely moving rats. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 1206–1214 (2006).

Yan, T. et al. Electrocorticographic effects of acute ketamine on non-human primate brains. J. Neural Eng. 19, e26034 (2022).

Średniawa, W. et al. Network and synaptic mechanisms underlying high frequency oscillations in the rat and cat olfactory bulb under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85705-5 (2021).

Nottage, J. F. et al. The effect of ketamine and D-cycloserine on the high frequency resting EEG spectrum in humans. Psychopharmacology 240, 59–75 (2023).

Hunt, M. J. et al. The olfactory bulb is a source of high-frequency oscillations (130–180 Hz) associated with a subanesthetic dose of ketamine in rodents. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 435–442 (2019).

Haberly, L. B. & Bower, J. M. Olfactory cortex: Model circuit for study of associative memory?. Trends Neurosci. 12, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(89)90025-8 (1989).

Luskin, M. B. & Price, J. L. The topographic organization of associational fibers of the olfactory system in the rat, including centrifugal fibers to the olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 216, 264–291 (1983).

Boyd, A. M., Sturgill, J. F., Poo, C. & Isaacson, J. S. Cortical feedback control of olfactory bulb circuits. Neuron 76, 1161–1174 (2012).

Boyd, A. M., Kato, H. K., Komiyama, T. & Isaacson, J. S. Broadcasting of cortical activity to the olfactory bulb. Cell Rep. 10, 1032–1039 (2015).

Li, Q. et al. Reinstating olfactory bulb-derived limbic gamma oscillations alleviates depression-like behavioral deficits in rodents. Neuron https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.013 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Cell-type-specific whole-brain direct inputs to the anterior and posterior piriform cortex. Front. Neural Circuits 14, 04 (2020).

Kajikawa, Y. & Schroeder, C. E. How local is the local field potential?. Neuron 72, 847–858 (2011).

Olszewski, M., Dolowa, W., Matulewicz, P., Kasicki, S. & Hunt, M. J. NMDA receptor antagonist-enhanced high frequency oscillations: Are they generated broadly or regionally specific?. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 1795–1805 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Collins, D. C. & Maier, J. X. Network dynamics in the developing piriform cortex of unanesthetized rats. Cerebral Cortex 31, 1334–1346 (2021).

González, J., Torterolo, P. & Tort, A. B. L. Mechanisms and functions of respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the primary olfactory cortex. Elife 12, 83044 (2023).

Adrian, E. D. Olfactory reactions in the brain of the hedgehog. J. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1942.sp003955 (1942).

Fontanini, A., Spano, P. & Bower, J. M. Ketamine–xylazine-induced slow (1.5 Hz) oscillations in the rat piriform (Olfactory) cortex are functionally correlated with respiration. J. Neurosci. 23, 7993–8001 (2003).

Tort, A. B. L., Brankačk, J. & Draguhn, A. Respiration-entrained brain rhythms are global but often overlooked. Trends Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2018.01.007 (2018).

Phillips, M. E., Sachdev, R. N. S., Willhite, D. C. & Shepherd, G. M. Respiration drives network activity and modulates synaptic and circuit processing of lateral inhibition in the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 32, 85–98 (2012).

Cordon, I. et al. Coupling in the cortico-basal ganglia circuit is aberrant in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 1375–1387 (2015).

Pittman-Polletta, B., Hu, K. & Kocsis, B. Subunit-specific NMDAR antagonism dissociates schizophrenia subtype-relevant oscillopathies associated with frontal hypofunction and hippocampal hyperfunction. Sci. Rep. 8, 11588 (2018).

Ye, T. et al. Ten-hour exposure to low-dose ketamine enhances corticostriatal cross-frequency coupling and hippocampal broad-band gamma oscillations. Front. Neural Circuits 12, 61 (2018).

Jurkiewicz, G. J., Hunt, M. J. & Żygierewicz, J. Addressing pitfalls in phase-amplitude coupling analysis with an extended modulation index toolbox. Neuroinformatics https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-020-09487-3 (2020).

Wróbel, J. et al. Nasal respiration is necessary for ketamine-dependent high frequency network oscillations and behavioral hyperactivity in rats. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75641-1 (2020).

Hansen, I. H. Investigation of Pharmacological Manipulation on Brain Connectivity in Rats and Humans for Improvement of Drug Development (Technical University of Denmark, 2019).

Shipley, M. T. & Adamek, G. D. The connections of the mouse olfactory bulb: A study using orthograde and retrograde transport of wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. Bull. 12, 669–688 (1984).

Neville Kevin, R. & Haberly, L. B. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain (Oxford UP, 2004).

Iravani, B. et al. Odor identity can be extracted from the reciprocal connectivity between olfactory bulb and piriform cortex in humans. Neuroimage 237, 118130 (2021).

Matsutani, S. & Yamamoto, N. Centrifugal innervation of the mammalian olfactory bulb. Anat. Sci. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-073x.2007.00223.x (2008).

Nagayama, S. et al. Differential axonal projection of mitral and tufted cells in the mouse main olfactory system. Front. Neural Circuits 4, 120 (2010).

Srinivasan, S. & Stevens, C. F. A quantitative description of the mouse piriform cortex. bioRxiv 145, 69 (2017).

Brys, I. et al. 5-HT2AR and NMDAR psychedelics induce similar hyper-synchronous states in the rat cognitive-limbic cortex-basal ganglia system. Commun. Biol. 6, 737 (2023).

Nicolás, M. J. et al. Ketamine-induced oscillations in the motor circuit of the rat basal ganglia. PLoS ONE 6, e21814 (2011).

Martin, J. H. & Ghez, C. Pharmacological inactivation in the analysis of the central control of movement. J. Neurosci. Methods 86, 145–159 (1999).

McColgan, T. et al. Dipolar extracellular potentials generated by axonal projections. Elife 6, 26106 (2017).

Chintaluri, C. et al. kCSD-python, reliable current source density estimation with quality control. PLoS Comput. Biol. 20, e1011941 (2024).

Chintaluri, C. et al. What we can and what we cannot see with extracellular multielectrodes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008615 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Agnieszka Kępczyńska, PhD (Laboratory of Electron Microscopy, Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology PAS) for help processing histology.

Funding

This work was financed by the National Science Centre (Poland) grant UMO-2021/41/B/NZ4/03882.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., W.S., and M.J.H. conducted the experiments. J.W., W.S., A.B., M.D., D.K.W., and M.J.H. analyzed the data and designed the figures. J.W. and M.J.H. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wróbel, J., Średniawa, W., Bramorska, A. et al. NMDA receptor antagonist high-frequency oscillations are transmitted via bottom-up feedforward processing. Sci Rep 14, 21858 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71749-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71749-w