Abstract

The spectral analysis of dynamical systems is a staple technique for analyzing a vast range of systems. But beyond its analytical utility, it is also the primary lens through which many physical phenomena are defined and interpreted. The turbulent energy cascade in fluid mechanics, a dynamical consequence of the three-dimensional Navier–Stokes equations in which energy “cascades” from large injection scales to smaller dissipation scales, is a well-known example that is precisely defined only in reciprocal space. Related techniques in the context of networked dynamical systems have been employed with great success in deriving reduced order models. But what such techniques gain in analytical tractability, they often lose in interpretability and locality, as the lower degree of freedom system frequently contains information from all nodes of the network. Here, we demonstrate that a network of nonlinear oscillators exhibits spectral energy transfer facilitated by an effective force akin to the Reynolds stress in turbulence, an example of an emergent higher order interaction. Then, introducing a filter-based decomposition motivated by large eddy simulation, we show that such higher order interactions can be localized to individual nodes and study the effects of local topology on such interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many problems of interest in a wide range of fields find their most natural representation as dynamics unfolding on complex networks. This ever-expanding list includes the spreading of viruses1,2, synchronization of neurons3 or people4, and the stability and robustness of the electricity grid5. A variety of methods have been introduced to characterize the multi-scale nature of such dynamics, including computational approaches like spectral coarse graining6 or renormalization7 and analytical equation-based methods via the derivation of mean-field models3 or other low-dimensional representations8.

Although not always leveraged as reduced order models, spectral representations of network dynamics4, which often arise from a linearization of the underlying problem, can lead to fruitful analysis. Observing the independent modes of a system near a dynamical fixed point can be used to relate dynamic scales (e.g., the synchronization time of oscillators) and topological ones (e.g., the eigenvalues of underlying networks)9 or to assess the stability of various low-dimensional fixed points of a high-dimensional system10.

But beyond solutions of linear or linearized problems, an adroit application of Fourier tools offers a way to precisely resolve the consequences of nonlinearity in the dynamics. In the network context, it has been increasingly recognized that a one-dimensional or lower-dimensional model of network dynamics suffers from generic inaccuracies owing to the nonlinearities of the governing equations. These inaccuracies can be quantified analytically and measured11, but the precise ways in which neglected scales influence the modeled dynamics is difficult to isolate. In fluid mechanics, where a turbulent flow state exists far from any fixed points or equilibria, Large-Eddy simulation (LES)12 and related filter-based techniques13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 have long grappled with the consequences of such nonlinearities, and are now a cornerstone of the simulation of large-scale flows like those found in the atmosphere and ocean22.

In the filter-based framework, through a filtering of the equations of motion, direct scale-dependent effective forcings can be derived for the individual scale-local modes of a system. This allows one to view phenomena like the scale-to-scale transfer of energy as the consequence of physical work being done by some scales of a system on other scales20. This interpretation leads to the introduction of a fictitious Reynolds stress, an effective stress representing the transfer of momentum from large-scale mean flow to smaller-scale turbulent fluctuations.

In this paper, we investigate a graph filtering methodology that allows us to introduce corresponding notions in the context of network dynamics. Applying this technique to a network of nonlinear oscillators, we show how the synchronization of the network is modified via spectral energy transfer between network modes facilitated by an effective force akin to the Reynolds stress. Further, we are able to localize such a higher order interaction to individual nodes in the network and comment on their topological dependence.

Spectral view of network dynamics

The Laplacian matrix is the fundamental building block of spectral graph theory, and is given by \(\textbf{L}=\textbf{D}-\textbf{A}\) where \(\textbf{A}\) is the graph adjacency matrix and \(\textbf{D}\) is the node degree matrix defined as \(\textbf{D}=\textrm{diag}(\sum _jA_{ij})\), with eigendecomposition \(\textbf{L}=\textbf{V}\varvec{\Lambda }\textbf{V}^T\) assuming the network is real and symmetric. For simplicity, we will focus on undirected networks. Just as the eigenfunctions of the discrete Laplace operator form the basis functions of the Fourier transform, the eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian can be used as a complete set to represent any graph signal—the naming convention of the matrix is not a coincidence.

While there is no strictly corresponding sense of frequency that the eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian inherit from the discrete Laplacian, there is an approximate one. Consider the metric of graph signal smoothness known as total variation23

a natural measure which will take small values when the signal varies smoothly across connected nodes. Treating the kth eigenvector of the graph Laplacian, \(v^{(k)}\), as a graph signal, we can see that \(\textrm{TV}(v^{(k)})=(v^{(k)})^TLv^{(k)}=\lambda ^{(k)}\), where \(\lambda ^{(k)}\) is its corresponding eigenvalue. Thus in ordering the graph eigenvectors by increasing eigenvalue as is typically done, they are also ordered by decreasing total variation. A projection of a signal f onto the eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian therefore captures its smoothness with respect to the underlying graph24.

Spectral oscillator dynamics

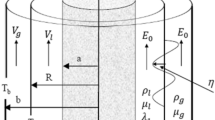

While this terminology was developed in the field of graph signal processing25,26,27, it can carry dynamical significance as well. To demonstrate this significance, we introduce a form of coupled, unforced Duffing-type oscillators governed by

While there are many other systems that have dynamically significant spectral representations28,29, we choose this model for its expository simplicity (c.f.30). The energy of a single oscillator, given by the quantity \(E_i = \frac{1}{2}\dot{x}_i^2+\frac{1}{2}\alpha x_i^2 + \frac{1}{4}\beta x_i^4\), evolves according to

so the total system energy \(E=\sum _iE_i\) evolves as

exactly the total variation of the oscillator velocity signal. This means that that energy is dissipated inversely proportionally to the smoothness of the velocities, which motivates us to write out Eq. (2) in its spectral representation, capturing precisely this important notion of smoothness.

If we define the kth spectral coefficient as \(\hat{x}_k=\sum _jv^{(k)}_jx_j\) and inversely \(x_i=\sum _kv^{(k)}_j\hat{x}_k\), we can manipulate Eq. 2 to become

where we have rewritten the final term in Eq. (5) by defining \(\zeta _{klmn}=\sum _iv^{(k)}_i v^{(l)}_iv^{(m)}_iv^{(n)}_i\). Pulling out the entirely scale-local contribution from the final term, we arrive at

A consequence of the cubic nonlinearity, the hypergraph \(\zeta _{klmn}\) weights the higher-order interactions between the spectral coefficients, an interesting example of emergent higher-order interactions described recently by Thibeault et al.31. They showed that, generically, many forms of dimension reduction will lead to higher-order interactions between the observables if there exists a non-commutativity between the equations of motion and the reduction technique itself (often a nonlinearity, but also for some linear operators). In our case, such higher-order interactions are interpretable as the transfer of kinetic energy between scales, with the hypergraph \(\zeta _{klmn}\) determining purely structural constraints on such transfer. Thus, viewing the system as independently evolving scales28 will necessarily abstract away such energy transfer and may obfuscate the dynamics of the system.

Such transfer of energy is a well studied problem in fluid mechanics, with one of the most illustrative examples being the study of decaying turbulence32,33. In two-dimensional turbulence where energy transfer is typically towards larger-scale modes, limited damping at the largest scales leads to the phenomenon of spectral condensation34. Here too, as energy is dissipated more efficiently at scales with larger associated eigenvalues, the transfer of energy holds dynamic relevance. At the largest scale (\(k=1\)), there is no dissipation as \(\lambda ^{(k)}=0\) and energy trapped at this mode will not dissipate.

Consider then the following example: taking an Erdos-Renyi random graph with \(N=100\) (number of nodes) and \(p=0.1\) (probability of an edge) and keeping \(\alpha =1\), \(\beta =1\), we initialize the network with spectral weight of \(\hat{x}\) and \(\dot{\hat{x}}\) in the lower third, middle third, and top third of wavenumbers k and allow the network to relax towards a synchronized state. These three forcings therefore correspond to injecting energy from the large scales, medium scales, or small scales; we run all three since various dynamical systems often exhibit energy transfer from either the large scales to the small scales (on average) or vice versa.

We observe that although only the prescribed modes are imparted with kinetic energy, other modes of the system are energized due to the flow of energy between scales. In Fig. 1 we show individual spectral weights evolving in logarithmic time (the greatest energy transfer occurs in the first few moments of the simulation). Note that although only a restricted band of wavenumbers is initially energized, additional modes appear active as the original modes decay, indicating significant energy transfer occurring across the modes of the network. Focusing then on just the bottom third of wavenumbers for all three simulations, we visualize the spectral velocity weight in Fig. 2. Interestingly, the modes are not uniformly energized or energized in a monotonic fashion; rather, specific modes activate depending on the forcing range in a nonuniform manner. Such a result is expected given the complexity of the spectral hypergraph \(\zeta _{klmn}\) which determines the allowable interscale transfer, but it is not straightforward to further analyze such a high rank tensor. Although all of the relevant information is contained therein, further techniques will make the study of this phenomenon more tractable.

From top to bottom, the same three cases as in Fig. 1. Note the different color ranges for the three panels.

Filtered view of network dynamics

Graph filtering is particularly suited to the study of such spectral phenomena as it has been defined largely through a spectral decomposition27. Filtering by a filter G can be written as

or indexed at each node as

where the filter g acts to attenuate or enhance spectral coefficients of a graph signal. We can define the unfiltered component of the signal to be \(\widetilde{f}=f-\overline{f}\) such that any signal can be written as the sum of its filtered component and an unfiltered residual.

An obvious candidate for filter choice is the smooth spectral filter given by \(g(\lambda ^{(k)},\kappa ,\gamma )=1-\frac{1}{1+\exp {(-\gamma (k-\kappa ))}}\), where larger modes with \(k<\kappa\) are preserved and smaller modes with \(k>\kappa\) are attenuated. The sharpness of the filter can be enhanced by increasing \(\gamma\), but for simplicity we take \(\gamma =1\). Although in equation (9) the filter is allowed to be a function of the eigenvalues of the network, this filter does not depend on the spectrum. A result is that the filtered signal can be easily interpreted as allowing all modes \(k<\kappa\). Figure 3 shows a graph signal before and after filtering with two different values of \(\kappa\) with their corresponding spectral representations.

One advantage of a filtering methodology is that imperfect information is not always a hindrance. To compute the spectral coefficients \(\hat{f}_k=\sum _iv^{(k)}_if_i\), every \(f_i\) must be known. Although the definition of Eq. (9) employs the spectral coefficients and so requires complete information, it is a general definition and many filtering operations can be computed at a local scale.

Consider, for example, the heat equation \(\partial _tx_i =\epsilon \sum _j L_{ij}x_j\). As the heat equation evolves over a graph, the individual heats \(x_i\) tend to a uniform state, so its advancement can be interpreted as interpolating between an entirely disordered and perfectly uniform state of a network. Such an equation also arises in the linearized form of Kuramoto oscillators, and has been studied extensively in the context of synchronization28. To advance the heat equation at a single node, all that must be known is the heat value of the node itself and the heat value of its neighbors.

A discrete update of the heat equation is equivalent to the filtering operation \(\overline{f}=Gf\) if we set \(G=I+\epsilon L\), so the filtering function looks like \(g(\lambda ^{(k)})=1-\epsilon \lambda ^{(k)}\). Such an operation therefore attenuates high frequency spectral coefficients preferentially over low frequency spectral coefficients. So although the heat equation can be viewed in a spectral form where all information is needed, it can also be advanced at a single node with only self and neighboring information.

Taking the limit of the discrete heat filter while fixing the total time T, one finds \(g(\lambda ^{(k)})=\exp (-\kappa \lambda ^{(k)})\) where \(\kappa =\epsilon T\). Although strictly interpreting the cutoff scale \(\kappa\) is now more challenging, one can directly observe its effect on the node space of the graph, and it can be computed for individual nodes without full information. An example of the application of the heat filter is shown in Fig. 4.

Filtered oscillator dynamics

Returning to our analysis of Eq. (2), instead of transforming it to a spectral representation, consider its form under the filtering operation. Filtering the entire equation and expanding as \(x_i=\overline{x_i}+\widetilde{x}_i\) when necessary, we can derive

where the emergent \(F_i^{R}\) we define as the Reynolds forcing, which can be written as

See supplementary materials for more details. In this way, we can view the filtered dynamics of the network as the same as the dynamics of individual oscillators with three additional and distinct forcing terms, a combination of the self-interactions of the large-scale degrees of freedom, cross-interactions between the large and small scales, and the self-interactions of the small scales. In the turbulence literature, the analogous effects are known as Leonard, cross, and subgrid stresses, respectively13; we therefore adopt similar nomenclature. We can also examine the energy of each filtered level by multiplying Eq. (10) with the filtered oscillator velocity to obtain

Looking back to the relaxation dynamics of the three cases examined in the earlier section, we can filter the oscillator at increasingly coarse scales and sum the energy transfer given by the last term of Eq. (12). The results are shown in Fig. 5.

From top to bottom, summed energy transfer for the same three cases as in Fig. 1. Values are summed over the full duraction of the simulation (\(T=10\)). The forcing range is shaded and corresponds to the most active transfer of energy.

As expected, the energy transfer is largest in the most energized wavenumbers, and net transfer is upwards towards larger scales. Interestingly, our triple decomposition reveals that although cross-scale energy transfer is almost exclusively active in the initialized regime, the self-interactions of the unfiltered scales peak at the bottom of this range and is active at larger scales as well. Additionally, it appears that the self-interactions of the filtered modes are unable to transfer energy across scales, a phenomenon also observed in the context of turbulent flows19.

Next, we perform a similar analysis on an ensemble of random graphs with initial conditions for each oscillator chosen uniformly at random in the interval \([-0.5,0.5]\). We generate ten random graphs and perform ten simulations for each graph. The average scale-dependent energy transfer summed over the entire simulation (\(T=10\)) is shown in Fig. 6. As before, we observe that the peak cross and subfilter energy transfer appear at different wavenumbers, but the net direction remains positive for almost all wavenumbers, excluding the bottom few.

Filtering methodology localizes higher order interactions

Having observed that the emergent higher order interactions give rise to a richness of behavior, our next step is to investigate to what extent these interactions can be analyzed at a node-local level, one of the advantages of a filter-based methodology. For the previously shown random initializations, we compute the average absolute energy transfer at nodes of a particular node degree. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

We observe that at the largest scales (e.g., \(k=10\)), nodes with lower degrees participate the most in scale energy transfer while the reverse occurs at smaller scales. Intermediate-scale filtering (e.g., \(k=50\)) smoothly interpolates between these two extremes, but the overall energy transfer is the same order of magnitude for all displayed scales (shown by Fig. 6). Such an observation is not possible from a perspective looking at only reduced order variables, and can be studied in the context of other reduced order models if similar filters can be produced.

Finally, we investigate to what extent this degree-dependent energy transfer can be dependent on the larger neighborhood of nodes. For this, we construct a \(10 \times 10\) grid where we connect the top half of nodes with weights equal to 1, and the bottom half are connected with weights equal to 10. This example also tests the effects of weighted graphs on our filtering methodology, as the Laplacian spectrum of weighted graphs has been shown in some cases to be qualitatively different from its unweighted counterpart35. We run 1000 simulations initializing the positions and velocities as before, and show the summed absolute energy transfer at individual nodes after filtering at two different scales in Fig. 8.

As before, nodes with lower degrees have in general larger associated Reynolds forcing when filtered at a large scale and smaller associated Reynolds forcing when filtered at a smaller scale. But there is also a longer-range structural component: the nodes in the center of the higher degree region have the smallest associated energy transfer (Fig. 8 left), while for the second case nodes at the boundary of the two regimes are more active than those at the center despite having a smaller degree.

Conclusion

To summarize, we have introduced and discussed a method for filtering possibly nonlinear dynamics on a complex network. Just as in the more familiar case of dynamics in continuous spaces, nonlinear dynamics on networks can lead to interactions between different scales. Using the filtering operations we describe, we are able to compute an effective Reynolds force that encodes these scale interactions and demonstrate its relevance for the synchronization of the system—and in particular not just the asymptotic outcome of the system (that is, a synchronized network) but also the dynamical approach to that outcome. As systems far from a synchronized or steady state are ubiquitous in real world application, we anticipate that tools to quantify deviation from linearity (e.g. the ability to quantify local scale interactions) will find use in engineering applications. This is particularly relevant when the time-varying aspects of the approach to synchrony are relevant, for example when transients can trip nonlinear instabilities.

Along these lines, one productive application of our work is towards predicting cascading failures in power networks36. While these networks tend to exhibit homophily in the steady state (large scale), failure often occurs at a single edge (small scale). Our results suggest that such a network may fail endogenously due to the transfer of energy from large scale synchronized structures towards the small scales: a single link in the extreme form. Understanding how exactly the structure of the network contributes to its spectral energy properties may prove essential in mitigating such failures. Our approach bridges the gap between these kinds of localized failures and the reduced order modeling of their parent systems.

Finally, even though we invoked fluid turbulence here only as the origin of the filtering techniques we adapted for use on networks, our results may also have bearing on our understanding and simulation of turbulence itself. Although the importance of scale-to-scale energy transfer in turbulence has been recognized for a century37, the detailed mechanisms that drive the turbulent energy cascade remain poorly understood38,39, largely due to the vast complexity of the turbulent state. Indeed, on algebraic multigrids reminiscent of our final example, the geometry of the grid can influence the scale transfer of simulated turbulence40. Our ability to quantify spectral energy transfer—using machinery already developed and well known in the context of fluid mechanics—in other, simpler systems may thus lead to the discovery of tractable test cases for fully understanding such structure-based effects.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brockmann, D. & Helbing, D. The hidden geometry of complex, network-driven contagion phenomena. Science 342, 1337–1342. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1245200 (2013).

Pastor-Satorras, R., Castellano, C., Van Mieghem, P. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 925–979. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.925 (2015).

Baladron, J., Fasoli, D., Faugeras, O. & Touboul, J. Mean-field description and propagation of chaos in networks of Hodgkin–Huxley and FitzHugh–Nagumo neurons. J. Math. Neurosci.https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-8567-2-10 (2012).

Laurence, E., Doyon, N., Dubé, L. J. & Desrosiers, P. Spectral dimension reduction of complex dynamical networks. Phys. Rev. X 9, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.9.011042 (2019).

Filatrella, G., Nielsen, A. H. & Pedersen, N. F. Analysis of a power grid using a Kuramoto-like model. Eur. Phys. J. B 61, 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e2008-00098-8 (2008).

Gfeller, D. & De Los-Rios, P. Spectral coarse graining of complex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.038701 (2007).

García-Pérez, G., Boguñá, M. & Serrano, M. Multiscale unfolding of real networks by geometric renormalization. Nat. Phys. 14, 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-018-0072-5 (2018).

Cestnik, R. & Pikovsky, A. Hierarchy of exact low-dimensional reductions for populations of coupled oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 54101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.054101 (2022).

Arenas, A., Díaz-Guilera, A. & Pérez-Vicente, C. J. Synchronization reveals topological scales in complex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett.https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.114102 (2006).

Strogatz, S. H. From Kuramoto to Crawford: exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators (Tech, Rep, 2000).

Kundu, P., Kori, H. & Masuda, N. Accuracy of a one-dimensional reduction of dynamical systems on networks. Phys. Rev. E 105, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.105.024305 (2022).

Pope, S. B. Turbulent Flows (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000).

Germano, M. Turbulence: the filtering approach. J. Fluid Mech. 238, 325–336 (1992).

Liu, S., Meneveau, C. & Katz, J. On the properties of similarity subgrid-scale models as deduced from measurements in a turbulent jet. J. Fluid Mech. 275, 83–119 (1994).

Eyink, G. L. Local energy flux and the refined similarity hypothesis. J. Stat. Phys. 78, 335–351 (1995).

Rivera, M. K., Daniel, W. B., Chen, S. Y. & Ecke, R. E. Energy and enstrophy transfer in decaying two-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 104502 (2003).

Chen, S., Ecke, R. E., Eyink, G. L., Wang, X. & Xiao, Z. Physical mechanism of the two-dimensional enstrophy cascade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 214501 (2003).

Chen, S. et al. Physical mechanism of the two-dimensional inverse energy cascade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 84502 (2006).

Liao, Y. & Ouellette, N. T. Spatial structure of spectral transport in two-dimensional flow. J. Fluid Mech. 725, 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2013.187 (2013).

Ballouz, J. G. & Ouellette, N. T. Tensor geometry in the turbulent cascade. J. Fluid Mech. 835, 1048–1064 (2018).

Ballouz, J. G. & Ouellette, N. T. Geometric constraints on energy transfer in the turbulent cascade. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 34603 (2020).

Maronga, B. et al. The parallelized Large-Eddy simulation model (PALM) version 4.0 for atmospheric and oceanic flows: model formulation, recent developments, and future perspectives. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 2515–2551. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-2515-2015 (2015).

Shuman, D. I., Narang, S. K., Frossard, P., Ortega, A. & Vandergheynst, P. The emerging field of signal processing on graphs: extending high-dimensional data analysis to networks and other irregular domains. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 30, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2012.2235192 (2013).

MacMillan, T. & Ouellette, N. T. Lagrangian scale decomposition via the graph Fourier transform. Phys. Rev. Fluids 7, 124401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.7.124401 (2022).

Saito, N. How can we naturally order and organize graph laplacian eigenvectors? 2018 IEEE statistical signal processing workshop. SSP 183–187, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/SSP.2018.8450808 (2018).

Ortega, A., Frossard, P., Kovacevic, J., Moura, J. M. & Vandergheynst, P. Graph signal processing: overview, challenges, and applications. Proc. IEEE 106, 808–828. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2018.2820126 (2018).

Sandryhaila, A. & Moura, J. M. Discrete signal processing on graphs: frequency analysis. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62, 3042–3054. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2014.2321121 (2014).

Mcgraw, P. N. & Menzinger, M. Laplacian spectra as a diagnostic tool for network structure and dynamics. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 77, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.77.031102 (2008).

Rodrigues, F. A., Peron, T. K., Ji, P. & Kurths, J. The Kuramoto model in complex networks. Phys. Rep.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.10.008 (2016).

Wang, Z., Cao, J., Duan, Z. & Liu, X. Synchronization of coupled Duffing-type oscillator dynamical networks. Neurocomputing 136, 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2014.01.016 (2014).

Thibeault, V., Allard, A. & Desrosiers, P. The low-rank hypothesis of complex systems. Nat. Phys.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02303-0 (2024).

Fang, L. & Ouellette, N. T. Multiple stages of decay in two-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Fluidshttps://doi.org/10.1063/1.4996776 (2017).

Billam, T. P., Reeves, M. T. & Bradley, A. S. Spectral energy transport in two-dimensional quantum vortex dynamics. Phys. Rev.https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.91.023615 (2014).

Fang, L. & Ouellette, N. T. Spectral condensation in laboratory two-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluidshttps://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.6.104605 (2021).

Drożdż, S., Kulig, A., Kwapień, J., Niewiarowski, A. & Stanuszek, M. Hierarchical organization of H. Eugene Stanley scientific collaboration community in weighted network representation. J. Inform. 11, 1114–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.09.009 (2017).

Schäfer, B., Witthaut, D., Timme, M. & Latora, V. Dynamically induced cascading failures in power grids. Nat. Commun.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04287-5 (2018).

Richardson, L. F. Weather Prediction by Numerical Process (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1922).

Carbone, M. & Bragg, A. D. Is vortex stretching the main cause of the turbulent energy cascade?. J. Fluid Mech. 883, R2 (2020).

Johnson, P. L. Energy transfer from large to small scales in turbulence by multiscale nonlinear strain and vorticity interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 104501 (2020).

Gordner, A., Nagele, S. & Wittum, G. Multigrid Methods for Large-Eddy Simulation. Tech. Rep.

Acknowledgements

T.M. acknowledges financial support from a Stanford Graduate Fellowship and from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1656518).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. derived the results and wrote and executed the code. T.M. and N.T.O. conceptualized the project and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

MacMillan, T., Ouellette, N.T. Spectral energy transfer on complex networks: a filtering approach. Sci Rep 14, 20691 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71756-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71756-x