Abstract

The gut microbiome of worms from composting facilities potentially harbors organisms that are beneficial to plant growth and development. In this experiment, we sought to examine the potential impacts of rhizosphere microbiomes derived from Eisenia fetida worm castings (i.e. vermicompost) on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, L.) plant growth and physiology. Our experiment consisted of a greenhouse trial lasting 17 weeks total in which tomato plants were grown with one of three inoculant treatments: a microbial inoculant created from vermicompost (V), a microbial inoculant created from sterilized vermicompost (SV), and a no-compost control inoculant (C). We hypothesized that living microbiomes from the vermicompost inoculant treatment would enhance host plant growth and gene expression profiles compared to plants grown in sterile and control treatments. Our data showed that bacterial community composition was significantly altered in tomato rhizospheres, but fungal community composition was highly variable in each treatment. Plant phenotypes that were significantly enhanced in the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments, compared to the control, included aboveground biomass and foliar δ15N nitrogen. RNA sequencing revealed distinct gene expression changes in the vermicompost treatment, including upregulation of nutrient transporter genes such as Solyc06g074995 (high affinity nitrate transporter), which exhibited a 250.2-fold increase in expression in the vermicompost treatment compared to both the sterile vermicompost and control treatments. The plant transcriptome data suggest that rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost can influence tomato gene expression and growth-related regulatory pathways, which highlights the value of RNA sequencing in uncovering molecular responses in plant microbiome studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbiomes are defined as the collection of microbial cells in a given environment1. They can be found in a variety of settings, including in and around multicellular eukaryotic organisms, such as plants. Each compartment of a plant from the roots to the leaves harbors taxonomically and functionally distinct microbiomes2,3. Similar to animals, plant microbiomes determine a variety of host traits and can be detrimental, neutral, or beneficial to the host4,5,6 and can be considered the ‘extended phenotype’ of the plant, given their influence on host fitness7. As a result, there is growing appreciation for the need to develop a molecular understanding of the responses and effects that phytobiomes may have on plant hosts and associated traits. Several trials involving the experimental manipulation of rhizosphere microbial communities have demonstrated how microbial consortia in the root zone can alter plant traits, such as aboveground biomass production8, flowering time9, and seed yield10, which may be a result of microbial nutrient cycling, phytohormone production, and other processes that influence plant productivity11,12,13. While much progress has been made in understanding the effects of the microbiome on host phenotypic traits, there is little understanding of how the rhizosphere microbiome influences the expression of genes and regulatory pathways of the plant host.

Prior studies have highlighted the influence of environmental factors on plant physiology, including gene expression and regulatory pathways. For example, Neugart et al.14 showed that the expression of genes associated with the production of secondary metabolites in kale plants is dependent on temperature and light intensity, while transcriptomic sequencing of tobacco plants by Yan et al.15 showed biochar application resulted in increased amino acid and lipid synthesis. In addition to such abiotic factors, biotic components of the environment, such as pathogens, have also demonstrated their abilities to modify plant transcriptomes. For example, research by Meng et al.16 demonstrated tobacco infection with Phytophthora nicotianae elicits the expression of genes associated with disease-resistance and other proteins. Other studies have also highlighted similar effects of single plant pathogens on host transcriptomes17,18,19, yet the effect of whole plant-associated microbiomes in the rhizosphere has received less attention. This is likely due in part to the complexity of the soil microbiome20. Nevertheless, given the effect of the environment on gene expression and research showing effects of experimentally manipulated rhizosphere microbiomes on host plant phenotypes, it is reasonable to hypothesize that plant transcriptomes will shift in response to changes in the composition of rhizosphere microbiomes. Understanding how the plant transcriptome changes in response to whole microbial consortia is necessary in developing a better understanding of plant-microbiome interactions, which could be leveraged in developing sustainable agricultural practices addressing food safety and food security challenges globally21.

In this experiment, we analyzed the effects of rhizosphere microbiomes on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) foliar and fruit responses with an emphasis on gene expression and regulatory pathway changes. Tomato plants were grown to maturity in the greenhouse with sterilized potting soil treated with one of three microbial inoculant treatments: a microbial inoculant created from vermicompost of Eisenia fetida red wiggler worms, a microbial inoculant created from sterile vermicompost, which served as a control for non-living microbiomes in the vermicompost inoculant, or a no-compost control inoculant. Given the beneficial effects vermicompost has been shown to have on plant performance22,23, we hypothesized that tomatoes grown with the inoculant containing living vermicompost microbiomes would display significant transcriptome responses compared to both control treatments, especially for key nutrient-associated pathways, with measurable phenotypic changes in the plant host. Our objectives for this study were to: (i) compare phenotypes between tomato plants grown with living vermicompost microbiomes in their rhizosphere to plants grown with the sterile vermicompost and no-compost control inoculants and (ii) compare plant transcriptomic profiles between our three inoculant treatments to understand effects of the rhizosphere microbiome on plant growth and physiology.

Methods

Preparation of microbial inoculants

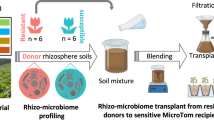

The experimental design is outlined in Fig. 1. The rhizosphere microbiomes in this experiment were derived from microbial inoculants prepared in the laboratory. For the vermicompost inoculant (V), 150 g of Worm Power (Avon, NY, USA) vermicompost derived from Eisenia fetida red wiggler worms was dissolved in 300 ml of sterile 10% Luria Broth, which was used in place of sterile water to help stimulate microbial growth. Sterilized glass beads were then added and the mixture was homogenized using an oscillating shaker set at 180 rpm for 1 h. The mixture was then filtered through four layers of sterilized cheese cloth and the resulting slurry was used as our vermicompost inoculant. For the sterile vermicompost inoculant (SV), we followed the same procedure using Worm Power vermicompost that was autoclaved twice with a 48-h resting period between cycles, which significantly reduces the living microbial community. This treatment was included to control for the effects of the living microbiome versus microbial natural products or nutrients present in the vermicompost. For the control inoculant (C), sterile 10% Luria Broth was used with no compost added, which served as our baseline treatment. The vermicompost inoculant used in this experiment contained 1.5–0.7–1.5 NPK with 1.6% calcium, 0.3% magnesium, 0.2% sulfur, and 0.1% iron.

Outline of plant inoculation and cultivation in the greenhouse with the vermicompost (V), sterile vermicompost (SV), and no-compost (C) control inoculants. In the growth chamber stage of our experiment (3 weeks), tomato seedlings were cultivated in magenta boxes filled with sterilized potting soil. Each seedling was first assigned to one of the three treatment groups. The seedlings then received the inoculant corresponding to their group and were cultivated in the growth chamber. After three weeks, the seedlings were then transferred to 6-inch pots and cultivated in a seedling greenhouse for one week to acclimate to a greenhouse environment. The seedlings were then transferred to a standard greenhouse for the remainder of the experiment, which lasted 13 weeks.

Greenhouse trial

Tomato plants (Ailsa Craig) were derived from the tomato germplasm collection at the United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Facility (USDA-ARS) Robert W. Holley Center for Agriculture and Health (Ithaca, NY, USA) and they were grown in a plant growth facility at Boyce Thompson Institute (Ithaca, NY, USA). We filled 15 magenta boxes with sterilized potting soil (50% metromix 360, 50% cornell mix + osmocote) to grow our seedlings. Each magenta box was randomly assigned to one of the three inoculant treatments, comprised of five replicate plants per treatment in this experiment. Before planting, each box received 20 ml of a solution made of 16 ml of one of the microbial inoculant treatments and 4 ml of 500 ppm Peter’s excel fertilizer (15–5–15 NPK). The solution was then mixed into the soil to keep the medium moist and to evenly distribute the fertilizer and inoculant solution. We then planted one pre-germinated Ailsa Craig seed into each magenta box and watered each seedling with 10 ml of sterile water.

After planting, the magenta boxes were placed in a growth chamber set at 250 µmol of light, 10% humidity, alternating between 28 °C for 16 h and 23 °C for 8 h for three weeks. Seedlings were then hardened off in the growth chamber, transplanted into 6-inch pots filled with the same sterilized potting soil, then placed in a seedling greenhouse to be hardened off before the rest of the experiment. The seedling greenhouse had day temperatures between 25 °C and 27 °C, night temperatures between 18 °C and 20 °C, and natural light and humidity. The seedlings were hand watered every day with tap water during this phase. Soils were covered with sterilized aluminum foil to reduce outside microbial contamination. After one week, tomatoes were transplanted into one-gallon pots filled with sterilized potting soil and placed in a new greenhouse with day temperatures between 24 °C and 26 °C, night temperatures between 21 °C and 23 °C, and natural light and humidity. The plants were kept in this greenhouse for the remainder of the experiment, which lasted 13 weeks. Plants were watered daily with tap water and fertilized with 150 ppm N Peter’s excel fertilizer three times a week. Sterilized aluminum foil was placed over the soil to reduce microbial contamination from the air. Aboveground plant biomass and rhizosphere soil samples were harvested three months after transplanting. Rhizosphere soil was collected by gently breaking up the tomato root ball, holding the roots, and gently shaking away unattached soil. The soil adhering to the roots was considered rhizosphere soil, which was sampled and stored at −20 °C for DNA extractions. Upon harvesting, plants were placed in a drying oven set at 60 °C for one week and total aboveground dry biomass (g) was then recorded.

Soil microbiome DNA extractions, sequencing, and analysis

DNA was extracted from rhizosphere soil samples collected at harvest using a PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturers protocol. Approximately 200–250 mg of frozen rhizosphere soil from each pot was used for each extraction. We then amplified the 16S rRNA and ITS gene sequences to capture bacterial and fungal taxonomic data using the PCR and sequencing procedures outlined in Bray et al.24. For the 16S rRNA gene, we used the primers 341F (5′-195 CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) and for the ITS gene we used the primers ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and 58A2R (5′-CTGCGTTCTTCATCGAT-3′). Following amplification, we performed an initial clean-up of our DNA using a HighPrep PCR Clean-up System (MAGBIO Genomics, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). We then attached unique index primers to the amplicons with a second PCR cycle. Indexed samples were then cleaned and normalized with a SequalPrep Normalization Plant Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) then added into two separate pools for 16S and ITS amplicons. The two pooled samples were then run on a 1.2% agarose gel with SyberSafe added and then the target band was excised. The pooled DNA samples were then extracted from the gel with a Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). We then submitted the pooled samples to the Cornell Genomic Facility (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA) for Illumina (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) barcoded sequencing on the MiSeq platform using a 600-cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 for the 16S rRNA gene pool and a 500-cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 for the ITS pool.

To process our bacterial and fungal sequences, we used a modified version of the pipeline from the Brazilian Microbiome Project (http://www.brmicrobiome.org/). Mothur v. 1.3613 was used to merge paired-end sequence (make.contigs), trim off primers (trim.seqs, pdiffs = 2, maxambig = 0), remove singletons (unique.seqs → split.abund, cutoff = 1), and classify sequences (97% similarity) using the GreenGenes v. 13.8 database for 16S rRNA gene sequences and UNITE v.7 database for ITS sequences. OTUs that were suspected to not be of fungal or bacterial origin were removed (remove.lineage). QIIME v. 1.9.114 was then used to cluster OTUs and create our bacterial and fungal OTU tables for statistical analysis in R (Rproject.org).

Analysis of tomato foliar and fruit phenotypes

Dried foliar tissue from each plant was used for analysis of foliar tissue nitrogen content at the Cornell Stable Isotope Laboratory (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA) using a Thermo Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) interfaced to an NC2500 elemental analyzer. The analysis provided information on δ15N as well as %N, which was used along with total aboveground dry biomass to calculate total foliar N (g).

To analyze the effect of inoculant treatment on fruit ethylene production, we harvested one fruit at the breaker stage from each plant during the trial and analyzed ethylene production based on modified procedures outlined in Nguyen et al.25. To allow wound ethylene to subside, fruits were left on the lab bench overnight before analysis. The following day, fruits were placed into sealed 250 ml air-tight mason jars and incubated for 3 h. We then drew 1 ml air samples from each mason jar and analyzed the sample using an Agilent 6850 GC System equipped with a flame ionization detector. Ethylene concentrations were then calculated by comparison with a standard of known concentration and normalizing of fruit mass. We recorded one measurement per fruit every day for four days.

To analyze how fruit carotenoid content may change in response to the rhizosphere microbiome, we harvested one mature green, breaker, and red ripe fruit from each plant and performed carotenoid extractions. After being harvested and remaining on the lab bench overnight, fruits were cut, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder. We then aliquoted ~ 100 mg of frozen ground tissue into 2 ml tubes with glass beads and lyophilized the samples. Each tube then received 50 μl of magnesium carbonate (MgCO3) at a 0.003 M concentration followed by 500 μl of 100% ethyl acetate. The tubes were then shaken for 30 s, incubated at 4 °C for 15 min, then shaken again. Samples were then centrifuged at max speed for 5 min, then the supernatant was transferred to a clean 2 ml tube. The samples were then dried down completely in a rotovap. The samples were analyzed using a slight modification of the method of Yazdani et al.26. The analysis began by dissolving the samples in an injection solvent made of ethyl acetate. This solvent also contained diindolylmethane (DIM) at a concentration of 0.05 mg/mL, which served as an internal standard for later quantification. Next, an ultra-performance convergence chromatography system (Waters UPC2) equipped with a Viridis HSS C18 SB column (3.0 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm particle size) was used to separate the compounds within the samples. The column temperature was set to 40 °C, and the mobile phase flowed at a rate of 1 mL/min.

To achieve this separation, a gradient elution technique was employed. This technique uses a two-part mobile phase system, consisting of supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) and methanol (MeOH). The gradual change in the ratio of these components over time helps to separate the various compounds within the sample. The chromatography column was initially equilibrated with 1% MeOH. To separate the analytes, a non-linear, concave gradient was applied. This gradient gradually increased the MeOH concentration to 20% over 7.5 min. The mobile phase composition was then held constant for an additional 4.5 min. Finally, the column was re-equilibrated back to its starting conditions with 1% MeOH over 3 min.

A Waters photodiode array (PDA) detector was used to monitor the presence of carotenoids by measuring their absorbance across a wavelength range of 250 nm to 700 nm. To quantify each specific carotenoid, we optimized a unique detection wavelength that balanced sensitivity (high signal) and selectivity (minimal interference from other compounds). Beta-carotene served as the calibration standard. Concentrations of all other carotenoids were then expressed as equivalents of beta-carotene using TargetLynx software within MassLynx 4.1 (Waters software).

Foliar and fruit tissue RNA extractions, sequencing, and analysis

In order to assess the effect of the rhizosphere microbiome on plant gene expression and regulatory pathways, we performed RNA extractions on tomato foliar and fruit tissue. We gathered foliar tissue from plants at four weeks old (Young) and at harvest (Mature). Foliar tissue was sampled from random leaves sampled towards the apical meristem on each plant and the composite sample was then immediately frozen, ground in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until extraction. Fruit tissue was gathered from 1–2 mature green (MG), breaker (BR), and red ripe (RR) fruits from each plant. Upon harvesting, we recorded the weight (g) of each fruit for our analysis of average fruit weight and left the fruit on the lab bench overnight to allow wound ethylene to subside. Fruits were then cut, frozen, and ground in liquid nitrogen. Powdered fruit samples were then stored at −80 °C until extraction.

RNA was extracted from foliar and fruit tissue using modified reagents and procedures from the Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA in each sample was then quantified using a nanodrop and ran on a 1% agarose gel to verify the RNA quantity and quality of each extract. Total RNA from foliar and fruit tissue was then used to construct strand-specific RNA libraries as described in Zhong et al.27 using the Illumina HiSeq platform at the Cornell DNA sequencing core facility.

Raw RNA-Seq reads were processed to remove adaptors and low-quality sequences using Trimmomatic (version 0.36) with default parameters28. Cleaned reads shorter than 40 bp were discarded. The remaining cleaned reads were aligned to the ribosomal RNA database29 using bowtie (version 1.1.2)30 allowing up to three mismatches, and those aligned were discarded. The remaining high-quality cleaned reads were aligned to the tomato reference genome (SL3.0 and ITAG3.2) using HISAT2 (version 2.1.0)31. Based on the alignments, raw read counts for each gene were calculated and then normalized to reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM). Raw read counts were then fed to DESeq232 to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between inoculant treatments across foliar and fruit developmental stages, with a cutoff of adjusted P value < 0.05 and fold change > 2. DEGs between inoculant treatments and across developmental stages are reported in Related File 1.

To gain insight into the influence of the microbiome on host developmental processes and regulatory pathways, we performed gene ontology (GO) analysis using the upregulated and downregulated genes reported in Related File 1. For each pairwise comparison between inoculant treatments across the foliar and fruit developmental stages, upregulated and downregulated gene lists were uploaded to agriGO v2.033, which provided enriched GO terms for each pairwise comparison. Complete results from the GO analysis are reported in Related File 2.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses of the rhizosphere microbiome and plant phenotype data were performed in R. After obtaining bacterial and fungal OTU tables in QIIME, the bacterial dataset was rarefied to 10,724 reads per sample and the fungal dataset was rarefied to 37 reads per sample, which were the lowest number of reads for a sample in each dataset. We then calculated Bray–Curtis distances between samples, which were utilized to perform a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and create an ordination to visualize differences in bacterial and fungal community composition between inoculant treatments. We then quantitatively assessed the effect of inoculant treatment on community composition with PERMANOVA using the adonis2 function. Due to a lack of adequate post hoc tests with adonis2, we could not perform pairwise comparisons of community composition between inoculant treatments following our analysis and only assessed the main effect of inoculant treatment on bacterial and fungal community composition. PERMANOVA requires homogeneity of variance, which we analyzed using the betadisper function. Shannon diversity indexes were then calculated for each sample and we compared the average Shannon diversity of the inoculant treatments using a linear model and the anova function to extract test statistics. We then used the emmeans function to perform pairwise comparisons of Shannon diversity between treatment groups. Model assumptions were verified using plotting methods. Stacked relative abundance plots were created to further visualize shifts in microbial taxonomic composition between inoculant treatments. Linear models were then passed through the anova function to determine the effect of inoculant treatment on relative abundances of the seven most abundant bacterial and fungal phyla and classes in the dataset. Model assumptions for each analysis were verified using plotting methods and data transformations were performed as necessary. We used the emmeans function to perform pairwise comparisons of mean relative abundances of each phylum and class between inoculant treatments. In cases where transformations did not help meet ANOVA assumptions, the Kruskal–Wallis Test was performed to assess the effect of treatment on relative abundances, followed by pairwise Wilcox tests to perform pairwise comparisons between treatment means.

To determine the effect of our inoculant treatment on total aboveground dry biomass and foliar nitrogen content we utilized linear models in R and implemented the anova function to extract test statistics. Normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were verified for each model using plotting methods. We then utilized the emmeans function to perform pairwise comparisons of inoculant treatment.

Mixed effect modeling with the lmer function in R was used to assess the effect of inoculant treatment, developmental stage, and the interaction between the two factors on average fruit weight, with treatment and developmental stage as fixed effects and plant replicate as a random effect. Normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were verified using plotting methods. The emmeans function in R was used to perform pairwise comparisons of group means. Mixed effect modeling with the lmer function was also used to determine the effect of inoculant treatment, day of measurement, and the interaction between the two factors on fruit ethylene production. Treatment and day of measurement were treated as fixed effects, while plant replicate was treated as a random effect. Normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were verified for each model using plotting methods. We used the emmeans function to perform pairwise comparisons of ethylene production between treatment groups and day of measurement. The effect of inoculant treatment, fruit ripening stage, and the interaction between the two factors on carotenoid content were assessed using linear mixed effect modeling with the lmer function with treatment and developmental stage treated as fixed effects and plant replicate treated as a random effect. Normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were verified for each model using plotting methods. Data transformations were performed as necessary to meet model assumptions. The emmeans function was used to perform pairwise comparisons of carotenoid content between the treatment groups and developmental stages. For these analyses involving two factors (i.e. inoculant treatment and development stage or time of measurement), we report and discuss the effects of the interaction term throughout the results section. Throughout the results, we report and discuss both p values below the 0.05 significance level and below the 0.1 significance level.

Results

Analysis of bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial sequence data showed samples clustered largely based on treatment along PCoA2 (Fig. 2A), indicating an effect of inoculant treatment on bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere. PERMANOVA indicated a significant effect of treatment on bacterial community composition (p = 0.018). Eigenvalues of the ordination are provided in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. Our data showed treatment did not have a significant effect on bacterial Shannon diversity indexes (p = 0.44) (Fig. 2B) or the relative abundances of the seven most abundant bacterial phyla (Fig. 2C). However, analysis of relative abundances of the seven most abundant bacterial classes revealed an effect of inoculant treatment on the abundance of Gammaproteobacteria at the p = 0.098 significance level, with an observed 110% increase in Gammaproteobacteria in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment at the p = 0.093 significance level (Fig. 2D). Additionally, the data revealed an effect of inoculant treatment on the abundance of bacteria unclassified at the class level at the p = 0.049 significance level, with an observed 95.2% increase in unclassified bacteria in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment at the p = 0.04 significance level (Fig. 2D). Relative abundances of bacterial phyla and classes for each individual sample are shown in Fig. S1AB in Supplementary Material.

(A) Principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) comparing rhizosphere bacterial communities in the vermicompost (V), sterile vermicompost (SV), and control (C) treatments at harvest with 95% confidence intervals around each treatment group and PERMANOVA analyzing the effect of inoculant treatment on community composition. (B) Comparison of mean Shannon diversity indexes between treatments at harvest. Letters represent pairwise comparison of group means using emmeans. (C) Comparison of the relative abundances of the most abundant bacterial phyla between treatments at harvest. (D) Comparison of the relative abundances of the most abundant bacterial classes between treatments at harvest. For all analyses, each treatment had n = 5 replicates.

Analysis of rhizosphere fungal communities showed high variability in fungal community composition (Fig. 3A), and PERMANOVA showed no effect of inoculant treatment on fungal community composition in our data (p = 0.39). Eigenvalues for the fungal PCoA are reported in Table S2 in Supplementary Material. ANOVA indicated there was no effect of inoculant treatment on Shannon diversity for fungi in this experiment (p = 0.88) (Fig. 3B). Additionally, we found high variability in the relative abundances of the most abundant fungal phyla and classes (Fig. 3CD), and our ANOVAs indicated there was no effect of inoculant treatment on the relative abundances on the seven most abundant fungal phyla and classes. Relative abundances of fungal phyla and classes for each individual sample are shown in Fig. S1CD in Supplementary Material.

(A) Principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) comparing rhizosphere fungal communities in the vermicompost (V), sterile vermicompost (SV), and control (C) treatments at harvest with 95% confidence intervals around each treatment group and PERMANOVA analyzing the effect of inoculant treatment on community composition. (B) Comparison of mean Shannon diversity indexes between treatments at harvest. Letters represent pairwise comparison of group means using emmeans. (C) Comparison of the relative abundances of the most abundant fungal phyla between treatments at harvest. (D) Comparison of the relative abundances of the most abundant fungal classes between treatments at harvest. For all analyses, each treatment had n = 5 replicates.

Tomato foliar and fruit phenotypes

Analysis of foliar phenotypes revealed a significant effect of treatment on aboveground dry biomass production (g) (p = 0.004). Plants in the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatment had a 35.7% and 35.9% increase in aboveground dry biomass production compared to plants in the control treatment at the p = 0.008 and p = 0.009 significance levels, respectively (Table 1). Data for aboveground dry biomass showed no differences between plants in the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments (p = 0.99). We found no effects of inoculant treatment on percent foliar nitrogen (p = 0.89). Inoculant treatment affected total nitrogen (g) at the p = 0.08 significance level, but pairwise analysis between inoculant treatments yielded no significant results (Table 1). Our analysis of foliar δ15N, which are often used as a proxy for soil nitrogen cycling activity, revealed a significant effect of inoculant treatment (p < 0.001). We found foliar δ15N was 31.4% higher in the vermicompost and 45.3% higher in the sterile vermicompost treatments compared to the control treatment at the p = 0.0003 and p < 0.0001 significance levels, respectively (Table 1). Foliar δ15N values did not differ between the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments (p = 0.12).

Analysis revealed the interaction between inoculation treatment and developmental stage did not have a significant effect on average tomato fruit weight (g) (p = 0.61) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, we found the interaction between inoculation treatment and day of sampling did not have a significant effect on the rate of fruit ethylene production (nL/g fruit/hour) (p = 0.37) (Fig. 4B). Analysis of fruit carotenoid production (ng/mg fruit dry weight) revealed an effect of the interaction between inoculant treatment and developmental stage on the production of phytoene at the p = 0.067 significance level (Fig. 5A). Pairwise comparisons revealed that at the red ripe developmental stage, fruits from the control treatment had 62.3% and 82.2% greater phytoene compared to fruits from the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments at the p = 0.055 and p = 0.015 significance levels, respectively. The interaction between inoculant treatment and developmental stage was insignificant when analyzing the production of phytofluene, lycopene, beta-carotene, and lutein (Fig. 5BCDE).

(A) Boxplot displaying average fruit weight (g) between the three treatments at the mature green (MG), breaker (BR), and red ripe (RR) developmental stages. For this analysis, we had n = 5 replicate plants per treatment and 1–2 fruits per plant for each developmental stage. Letters represent pairwise comparisons of treatment means at each developmental stage. (B) Boxplot displaying average fruit ethylene production (nL/g fruit/hour) for the vermicompost (V), sterile vermicompost (SV), and control (C) treatments across a four days (D) of measurements. For this analysis, we had n = 5 replicate plants per treatment and one breaker fruit per plant. Letters represent pairwise comparisons of treatments means at each day of measurement.

(A) Boxplot displaying average fruit phytoene content (ng/mg fruit dry weight) for the vermicompost (V), sterile vermicompost (SV), and control (C) treatments across the mature green (MG), breaker (BR), and red ripe (RR) developmental stages. (B) Boxplot displaying average fruit phytofluene content (ng/mg fruit dry weight) for the three treatments across the MG, BR, and RR developmental stages. (C) Boxplot displaying average fruit lycopene content (ng/mg fruit dry weight) for the three treatments across the MG, BR, and RR developmental stages. (D) Boxplot displaying average fruit beta-carotene content (ng/mg fruit dry weight) for the three treatments across the MG, BR, and RR developmental stages. (E) Boxplot displaying average fruit lutein content (ng/mg fruit dry weight) for the three treatments across the MG, BR, and RR developmental stages. For these analysis, we had n = 5 replicate plants per treatment and one fruit from each developmental stage for each plant. Letters represent pairwise comparisons of treatment means at each developmental stage.

Tomato foliar and fruit RNA-seq

Analysis of tomato plant RNA sequences revealed thousands of differentially expressed genes between inoculant treatments, including several genes involved in nutrient uptake and transport, as hypothesized (Related File 1). In young leaf tissue, we observed a 10.25 fold increase in the expression of Solyc10g076480 (ammonium transporter) in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment (p < 0.001). Additionally, we observed a 4.68 fold increase in the expression of Solyc10g076480 in the vermicompost treatment compared to the sterile vermicompost treatment (p = 0.047). In mature leaf tissue, we observed plants in the vermicompost treatment had 201.3- and 4681.1-fold increased expression of Solyc06g005813 (copper transporter) compared to the sterile vermicompost and control treatments at the p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 significance levels, respectively. Plants in the vermicompost treatment also had 250.2-fold increased expression of Solyc06g074995 (high affinity nitrate transporter) compared to both the sterile vermicompost (p = 0.027) and control (p = 0.036) treatments. Additionally, plants in the vermicompost treatment had 173-fold increased expression of Solyc06g051860 (mycorrhiza-inducible inorganic phosphate transporter) compared to the sterile vermicompost (p < 0.001) and control (p < 0.001) treatments. In red ripe fruit tissue, we observed plants in the vermicompost treatment had 157.5 fold increased expression of Solyc06g069730 (chlorophyll a-b binding protein) compared to both the sterile vermicompost (p = 0.01) and control (p = 0.016) treatments.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed several GO terms were enriched in the vermicompost treatment compared to the controls (Related File 2). GO analysis of foliar genes that were upregulated in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment at the young developmental stage showed an enrichment for GO terms such as GO:0006793 (phosphorus metabolic process, p < 0.001), GO:0051171 (regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process, p < 0.001), and GO:0005506 (iron ion binding, p = 0.0014) among several other terms. Analysis of foliar genes that were upregulated in the vermicompost treatment compared to the sterile vermicompost treatment at maturity showed enrichment for GO:0006793 (phosphorus metabolic process, p < 0.001) and GO:0006796 (phosphate-containing compound metabolic process, p < 0.001). Additionally, analysis of foliar genes that were upregulated in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment at maturity also showed enrichment for GO:0006793 and GO:0006796 at the p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 significance levels, respectively. In red ripe fruits, analysis of upregulated genes revealed enrichment for GO:0015979 (photosynthesis, p < 0.001), GO:0009765 (photosynthesis, light harvesting, p < 0.001), and GO:0019684 (photosynthesis, light reaction, p < 0.001) along with additional GO terms in the vermicompost treatment compared to the sterile vermicompost treatment. Additionally, analysis of genes upregulated in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment revealed enrichment for GO:0015979 (p < 0.001), GO:0009765 (p < 0.001), and GO:0019684 (p < 0.001) along with additional GO terms.

Discussion

Here we report the effects of rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost on tomato foliar and fruit phenotypes and transcriptomes. Our analysis of soil microbiomes in this experiment showed inoculant treatment influenced bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere, with an increase in the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and bacteria unclassified at the class level in the vermicompost inoculant treatment compared to the control treatment. In contrast, the fungal ITS data showed high variability in all three inoculant treatments. Given results from previous experiments with vermicompost22,23, we hypothesized rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost would significantly alter tomato gene expression, especially as related to nutrient metabolism, transport, and associated regulatory pathways, in addition to altering plant phenotypes as compared to both control treatments. Although plant phenotypes were similar between the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments, analysis of foliar and fruit transcriptomes revealed altered gene expression between the vermicompost treatment and both control treatments. These changes included the upregulation of key nutrient transporters in foliar tissue and the upregulation of photosynthetic genes in red ripe fruits in the vermicompost treatment. Together, our results suggest rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost could alter aspects of tomato growth and development, including nutrient transport, and demonstrate the usefulness of whole transcriptome profiling in studying plant-microbiome interactions.

Our sequencing data of rhizosphere microbial communities suggested inoculant treatment had an effect on bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere. Rhizosphere bacterial communities in this experiment showed overall shifts in community composition according to our PCoA as samples clustered by inoculant treatment along PCoA2, and PERMANOVA further indicated an effect of inoculant treatment. As demonstrated in previous research, such shifts in community composition can correspond to functional changes in the microbiome that could play a role in regulating plant growth and development34. In addition to altering overall community composition, our bacterial sequencing data revealed an increase at p < 0.1 in the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in the vermicompost treatment compared to the control treatment. Previous research has shown that Gammaproteobacteria may play a significant role in soil nitrogen cycling. For example, Nelson et al.35 demonstrated through metagenomic sequencing that genera within the Gammaproteobacteria class can contain multiple nitrogen cycling gene pathways. Additionally, recent work by Ren et al.36 found that Gammaproteobacteria could promote nitrogen cycling in plant rhizospheres in nutrient depleted soils. Considering this, one of the mechanisms through which rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost might alter plant productivity is through enhanced nitrogen cycling activity in the soil by taxonomic groups such as Gammaproteobacteria.

Fungi play a central role in a variety of rhizosphere processes, including nutrient solubilization, plant nutrient capture, and disease suppression37,38,39. Previous research in tomato has highlighted the beneficial effects of genera such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) on plant growth and stress tolerance40,41. Given the growth promoting effects vermicompost has been shown to have in previous studies, we expected to observe shifts in fungal composition in the vermicompost treatment, including an increase in beneficial fungi such as AMF, that could correspond to enhanced plant productivity. However, we were not able to observe such differences in the dataset from this experiment, largely due to the high variability in our fungal sequencing data. Considering the role of fungal symbionts such as AMF in supporting plant growth and stress tolerance42, further research characterizing fungal communities in vermicompost and their potential influence on host plants such as tomato is needed and will aid in developing a more holistic picture of vermicompost microbiomes.

We hypothesized that rhizosphere microorganisms derived from vermicompost may promote soil nutrient cycling (especially nitrification) and plant nutrient uptake, which would enhance aboveground biomass production and nitrogen capture. From our phenotyping, we observed an increase in aboveground biomass production and foliar δ15N, a proxy for soil nitrogen cycling with higher values generally representing enhanced nitrogen cycling activity43, in both the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments. It is worth considering that the growth promotion observed in these two treatments may have been due to two different mechanisms in our experiment. In the vermicompost treatment, plants could have captured more nutrients via the upregulation of nutrient transporter genes by the microbiome, as shown in our transcriptome data with the upregulation of genes such as Solyc06g074995 (high affinity nitrate transporter) in the vermicompost treatment compared to both control treatments. Additionally, the observed increase in δ15N and aboveground biomass production suggest rhizosphere microbial communities derived from vermicompost may have accelerated nitrification in soil, leading to enhancements in the expression of nitrogen uptake and transport genes in tomato. On the other hand, plants in the sterile vermicompost treatment could have more readily accessible nutrients released during microbial cell lysis as a result of the sterilization process of the vermicompost via autoclaving, which is supported by the observed increase in foliar δ15N.

Fruit maturation and quality traits such as ethylene production and carotenoid content remained largely unchanged between the treatments. However, we did observe a change in phytoene content at the red ripe developmental stage, with fruits from the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatment showing a decrease in phytoene compared to the control treatment. The carotenoid pathway is a complex multistep process that is regulated by numerous genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors44. The accumulation of the predominant downstream carotenoids that accumulate in tomato fruit (lycopene and beta-carotene) remained largely unchanged. The observed difference in phytoene accumulation, the first committed product in carotonogenesis, which in many plant tissues, including ripening tomato fruit, accumulates only transiently, suggests some effect of inoculant treatment on carotenoid pathway flux. As phytoene is the first product in the carotenoid pathway, effects of rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost on carotenoid production could be through reduction of early pathway activities and/or acceleration of later activities prior to lycopene and beta-carotene synthesis or in downstream carotenoid catabolism. However, further experimentation would be needed to verify this possibility.

Analysis of foliar and fruit transcriptomes revealed effects of the vermicompost microbiome that were not directly captured through plant phenotyping but could possibly be related to increased vegetative growth. We observed an enrichment for GO terms associated with nutrient transport and metabolism in the vermicompost treatment compared to both controls. These results suggest rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost may promote foliar growth and developmental processes through altering nutrient cycling and uptake activities, which is supported through our transcriptome data showing the upregulation of genes such as Solyc06g074995 (high affinity nitrate transporter) in the vermicompost treatment. Here, it is worth considering the growth conditions in this experiment. Plants were fertilized three times a week with 150 ppm N Peter’s excel fertilizer, a more liberal fertilizer regime, in order to ensure plants grew to maturity, produced fruit, and survived until harvest. Additionally, no stressors were applied during the experiment to ensure adequate plant growth and survival. Therefore, it is conceivable that the upregulation of nutrient transporter genes mediated by rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost may confer a fitness advantage if abiotic stress were imposed on the plants. Previous research has shown these types of interactions occurring in phytobiomes45,46,47, with the rhizosphere bolstering plant growth and fitness when subjected to various environmental stressors.

Our analysis also revealed enrichment for GO terms associated with photosynthesis in red ripe fruits from the vermicompost treatment compared to both control treatments. Additionally, pairwise comparisons of gene expression between treatments showed chlorophyll a-b binding proteins were upregulated in the vermicompost treatment compared to both controls (Related File 2). These results suggest an effect of inoculant treatment on fruit developmental processes and, specifically, a delay in the chloroplast to chromoplast transition. These data along with our analysis of fruit phytoene content at the red ripe stage further suggests rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost may alter earlier steps of carotenoid production in fruits, possibly steps involving the conversion from chlorophyll to carotenoid accumulation in fruits.

Conclusion

In this study, we compared the rhizosphere microbiome, plant phenotypes, and foliar and fruit transcriptomes between tomato plants grown with either a vermicompost inoculant, a sterile vermicompost inoculant, or a no-compost control to understand potential effects of the rhizosphere microbiome on plant growth and gene expression. Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing data indicated rhizosphere bacterial communities were distinct between the three inoculant treatments in this experiment, and plants from the vermicompost inoculant treatment had increased relative abundance of bacterial phyla such as Gammaproteobacteria in their rhizospheres compared to plants in the no-compost control. In contrast, fungal communities remained highly variable in all three inoculant treatments. While tomato plants in the vermicompost and sterile vermicompost treatments had similar increases in plant productivity compared to the no-compost control, analysis of foliar and fruit transcriptome data revealed rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost enhanced the expression of genes associated with nutrient transport in foliar tissue, in addition to genes associated with altering the transition in fruit maturation to ripening. These results highlight the potential growth altering capabilities of rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost. Altogether, our experiment broadly highlights the effects of plant-associated microbiomes on host transcriptomes and growth and demonstrate the usefulness of molecular techniques such as plant transcriptomics in capturing these effects at a finer level to both help explain phenotypic differences and inform new hypotheses for phytobiome studies.

Data availability

The raw sequence datasets generated in this study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive. Bacterial and fungal sequences can be accessed via accession PRJNA964452. Tomato RNA sequences can be accessed via accession PRJNA965799. Additional datasets generated during this experiment are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Berg, G. et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0 (2020).

Brown, S. P., Grillo, M. A., Podowski, J. C. & Heath, K. D. Soil origin and plant genotype structure distinct microbiome compartments in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00915-9 (2020).

Gopal, M. & Gupta, A. Microbiome selection could spur next-generation plant breeding strategies. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01971 (2016).

Babalola, O. O. et al. The nexus between plant and plant microbiome: Revelation of the networking strategies. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.548037 (2020).

Compant, S., Samad, A., Faist, H. & Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2019.03.004 (2019).

Ulrich, D. E., Sevanto, S., Ryan, M., Albright, M. & Johansen, R. Dunbar J Plant-microbe interactions before drought influence plant physiological responses to subsequent severe drought. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36971-3 (2019).

Hawkes, C. et al. Extension of plant phenotypes by the foliar microbiome. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-080620-114342 (2021).

Swenson, W., Wilson, D. S. & Elias, R. Artificial ecosystem selection. PNAS https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.150237597 (2000).

Panke-Buisse, K., Poole, A., Goodrich, J., Ley, R. & Kao-Kniffin, J. Selection on soil microbiomes reveals reproducible impacts on plant function. ISME J. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.196 (2015).

Garcia, J. et al. Selection pressure on the rhizosphere microbiome can alter nitrogen use efficiency and seed yield in Brassica rapa. Commun. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03860-5 (2022).

Hakim, S. et al. Rhizosphere engineering with plant growth-promoting microorganisms for agriculture and ecological sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.617157 (2021).

Trivedi, P., Leach, J., Tringe, S., Sa, T. & Singh, B. Plant-microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1 (2020).

Qu, Q. et al. Rhizosphere microbiome assembly, and its impact on plant growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00073 (2022).

Neugart, S., Krumbein, A. & Zrenner, R. Influence of light and temperature on gene expression leading to accumulation of specific flavonol glycosides and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives in kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica). Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00326 (2016).

Yan, S., Niu, Z., Yan, H., Zhang, A. & Liu, G. Transcriptome sequencing reveals the effect of biochar improvement on the development of tobacco plants before and after topping. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224556 (2019).

Meng, H. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals resistant and susceptible genes in tobacco cultivars in response to infection by Phytophthora nicotianae. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80280-7 (2021).

Nobori, T. et al. Transcriptome landscape of a bacterial pathogen under plant immunity. PNAS https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800529115 (2018).

Willig, C. J., Duan, K. & Zhang, Z. J. Transcriptome profiling of plant genes in response to Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2018_115 (2018).

Liu, M. et al. Arbuscular myccorhizal fungi inhibit necrotrophic, but not biotrophic, aboveground plant pathogens: A meta-analysis and experimental study. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19392 (2023).

Garcia, J. & Kao-Kniffin, J. Microbial group dynamics in plant rhizospheres and their implications on nutrient cycling. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01516 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Rational management of the plant microbiome for the Second Green Revolution. Plant Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2024.100812 (2024).

Azarmi, R., Ziveh, P. S. & Satari, M. R. Effect of vermicompost on growth, yield and nutrition status of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum). Pak. J. Biol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2008.1797.1802 (2008).

Toor, M., Kizilkaya, R., Anwar, A., Koleva, L. & Eldesoky, G. Effects of vermicompost on soil microbiological properties in lettuce rhizosphere: An environmentally friendly approach for sustainable green future. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117737 (2024).

Bray, N., Kao-Kniffin, J., Frey, S., Fahey, T. & Wickings, K. Soil macroinvertebrate presence alters microbial community composition and activity in the rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00256 (2019).

Nguyen, C. et al. Tomato GOLDEN2-LIKE transcription factors reveal molecular gradients that function during fruit development and ripening. Plant Cell. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.118794 (2014).

Yazdani, M., Croen, M. G., Fish, T. L., Thannhauser, T. W. & Ahner, B. A. Overexpression of native ORANGE (OR) and OR mutant protein in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii enhances carotenoid and ABA accumulation and increases resistance to abiotic stress. Metab. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2021.09.006 (2021).

Zhong, S. et al. High-throughput Illumina strand-specific RNA sequencing library preparation. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011, 940–949 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2013).

Langmead, B. Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi1107s32 (2010).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Tian, T. et al. agriGO v.20: A GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx382 (2017).

Chepsergon, J. & Moleleki, L. Rhizosphere bacterial interactions and impact on plant health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2023.102297 (2023).

Nelson, M., Martiny, A. & Martiny, J. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601070113 (2016).

Ren, Y. et al. Functional compensation dominates the assembly of plant rhizospheric bacterial community. Soil Biol. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107968 (2020).

Singh, H. & Reddy, M. Effect of inoculation with phosphate solubilizing fungus on growth and nutrient uptake of wheat and maize plants fertilized with rock phosphate in alkaline soils. Eur. J. Soil Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2010.10.005 (2011).

Moreau, D., Bardgett, R. D., Finlay, R. D., Jones, D. L. & Philippot, L. A plant perspective on nitrogen cycling in the rhizosphere. Funct. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13303 (2019).

Qiao, Q. et al. Characterization and variation of the rhizosphere fungal community structure of cultivated tetraploid cotton. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207903 (2019).

Begum, N. et al. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01068 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Rhizosphere microbes enhance plant salt tolerance: Toward crop production in saline soil. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2022.11.046 (2022).

Fasusi, O., Babalola, O. & Adejumo, T. Harnessing of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in agroecosystem sustainability. CABI Agric. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-023-00168-0 (2023).

Xu, Y., He, J., Cheng, W., Xing, X. & Li, L. Natural 15N abundance in soils and plants in relation to N cycling in a rangeland in Inner Mongolia. J. Plant Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtq023 (2010).

Liu, L., Shao, Z., Zhang, M. & Wang, Q. Regulation of carotenoid metabolism in tomato. Mol. Plant. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.006 (2015).

Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., Li, P. & Qi, X. Responses of the maize rhizosphere soil environment to drought-flood abrupt alternation stress. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1295376 (2023).

Liao, Z. et al. Chapter Three—Response network and regulatory measures of plant-soil-rhizosphere environment to drought stress. Adv. Agron. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2023.03.002 (2023).

Sharma, K., Gupta, S., Thokchom, S. D., Jangir, P. & Kapoor, R. Arbuscular mycorrhiza-mediated regulation of polyamines and aquaporins during abiotic stress: Deep insights on the recondite players. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.642101 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lynn Marie Johnson, Liang Cheng, Yimin Xu, Julia Vrebalov, Brian Bell, and Jay Miller for their assistance with this research.

Funding

This work was supported by an Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Grant [2016-67013-24414] from the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture. J.G. was supported by fellowships from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF-GRFP) [DGE-1650441] and the McNair State University of New York Diversity Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G., J.K., and J.G. designed the experiment. J.G., M.M., T.F., J.P.S. and T.T. conducted the experiment. J.G. and Z.F. analyzed the data. J.G., J.K., and J.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript preparation and revision. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia, J., Moravek, M., Fish, T. et al. Rhizosphere microbiomes derived from vermicompost alter gene expression and regulatory pathways in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, L.). Sci Rep 14, 21362 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71792-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71792-7