Abstract

This study aimed to assess the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in patients with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) by analyzing changes in visual acuity (VA) and enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) parameters. A comparative retrospective study was conducted by reviewing the medical records of all HBO-treated RAO patients in our department and comparing them with matched RAO patients who did not receive HBO treatment. All patients treated with HBO received treatment within 7 days of the onset of visual symptoms. Baseline characteristics were compared, and VA and OCT parameters were evaluated at baseline and follow-up visits. A total of 50 eyes from 50 patients were included, with 29 eyes in the HBOT group and 21 eyes in the control group. The mean BCVA of the HBOT group at the initial visit was 2.03 logMAR, which improved to 1.55 logMAR at 6 months, with the change being statistically significant (P < 0.01), while the control group's BCVA remained almost unchanged, from 2.1 to 2.11 logMAR (P = 0.762). The central choroidal thickness increased significantly in the HBOT group over the subsequent period. The central fovea, and outer retinal layer thickness in the HBOT group were significantly greater than those in the control group at the 6-month follow-up after treatment. HBOT appears to be effective in improving VA and inducing favorable changes in OCT parameters in patients with CRAO. It helps to preserve retinal layer thickness, especially in the outer retinal layer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinal Artery Occlusion (RAO) is an infrequent yet critical eye emergency resulting in painless, unilateral visual and/or visual field impairment1. During the initial presentation, visual acuity varies from counting fingers to light perception in 74% to 90% of cases. In instances of central RAO (CRAO) diagnosis, 90% of patients ultimately exhibit a visual acuity of 20/400 or lower2,3. Consequently, the visual prognosis, particularly in cases of CRAO, is bleak, with minimal prospects for visual enhancement4.

These interventions encompass ocular massage, reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) through anterior chamber paracentesis, or using pressure-lowering medications to facilitate the dislodgment of the embolus downstream5,6. Additionally, vasodilation of retinal vessels can be achieved through sublingual isosorbide dinitrate and inhalation of carbon dioxide or carbogen4. More recent approaches, such as intra-arterial fibrinolysis (LIF), surgical embolectomy, or neodymium:yttrium–aluminium–garnet laser embolysis, have been explored7,8,9. However, none of these treatments has demonstrated both effectiveness and safety, and currently, there is no established standard of care for managing.

In normal breathing conditions with room air, blood oxygen hemoglobin saturation can reach nearly 100%. Approximately 15% of oxygen supply to the retina under normoxic conditions is derived from the choroidal circulation, which nourishes the outer retinal layers10. Inhalation of 100% oxygen at high atmospheric pressure enhances oxygen solubility in the blood (from 0.3 up to 6 vol%)11. This hyperoxia enables the choroidal vasculature to deliver more oxygen to the retinal tissue and vitreous body, potentially sustaining the retina through diffusion in cases of artery occlusion until vascular recanalization occurs12,13,14. This concept has led to the development of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for patients with RAO, allowing oxygen diffusion into the inner retinal layers through the choroidal vessels and the vitreous body. Various authors have reported potential beneficial effects of hyperbaric therapy on visual acuity in cases of CRAO10,15,16,17,18. However, as they have primarily sought to establish the efficacy of HBOT through improvements in visual acuity or subjective symptoms, none of these studies have demonstrated the effects of HBO therapy on anatomical changes or influences on the anatomical structure.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging modality based on interferometry, utilizing low-coherence light to provide in vivo high-resolution quasi-histologic images of the retina19. Given its capability to capture cross-sectional images of the retina, OCT is primarily employed for measuring the thickness of retinal structures. Recent advancements, such as improved speed and enhanced depth imaging (EDI) techniques, have enabled deeper penetration, allowing for the evaluation of the choroid20. OCT stands out as one of the accurate methods for assessing treatment efficacy in various retinal diseases. Several OCT biomarkers have been proposed to predict both functional and anatomical outcomes associated with different treatments21,22,23. Previous studies revealed that CRAO leads to thickening of both inner and outer retinal layers in the acute stages, followed by subsequent atrophic changes in both the inner and outer retina24. However, there is currently no study that systematically evaluates serial OCT changes in patients undergoing HBO treatment and investigates potential prognostic anatomical factors as revealed by OCT.

Therefore, we have initiated a prospective study to analyze changes in the thickness of retinal components using OCT in patients with CRAO who underwent HBOT. The aim is to uncover anatomical differences between patients undergoing HBOT and those without HBOT. The secondary objective of this study is to explore whether baseline OCT anatomical features and biomarkers are linked to the treatment response to HBOT in eyes affected by CRAO.

Methods

The present study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, and adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki was ensured.

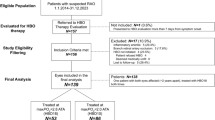

We conducted an analysis of the medical records of all patients admitted to our clinic between December 2015 and December 2023 who presented with visual loss confirmed through angiography as unilateral non-arteritic CRAO. Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) received a diagnosis of complete or subtotal non-arteritic CRAO with symptom onset within 7 days; (2) underwent fluorescein angiography and spectral domain (SD)-OCT (Spectralis OCT; Heidelberg Engineering Inc, Heidelberg, Germany) during the initial visit. Patients with a preserved cilioretinal artery, as well as those with arteritic CRAO, were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of ocular trauma or the presence of macular disease, severe nonproliferative or proliferative diabetic retinopathy, other retinal vascular diseases, glaucoma, myopic retinopathy, ocular surgery other than cataract surgery or any other conditions that could interfere with OCT images in either eye; (2) Patients with a follow-up of less than 6 months.

The primary objective for all patients was to administer emergency HBOT sessions and standard treatment as swiftly as possible. HBOT was implemented as a rescue therapy for patients facing more critical situations and when the urgency for therapeutic success was higher. The standard treatment protocol included ocular massage, along with the administration of intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering agents, specifically topical timolol 0.5%, and oral acetazolamide 500 mg. Patients received standard treatment only in instances where systemic contraindications prevented the administration of HBOT, when patients declined this procedure, or when the medical compression chamber was unavailable. These patients constituted the control group. Treatment is administered at 2.8 atmosphere absolute (ATA) in a mono-place chamber (IBEX M2; Ibex Medical Systems, Seoul, Korea) or multi-place chamber (IBEX; Ibex Medical Systems), utilizing 100% oxygen for 90 min twice daily in the first three days, and 120 min once daily thereafter. The aim of our oxygen therapy was to undergo continuous treatment for 14 days.

All subjects underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination, which included measuring best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using the Snellen chart, assessing intraocular pressure, conducting a slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination, capturing color fundus photography, performing fluorescein angiography, and conducting an OCT examination. EDI-OCT images were acquired using a Spectralis OCT instrument (Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) with seven horizontal lines covering 20 × 20 degrees through the center of the fovea. The eye tracking system in this instrument was utilized to capture each image, and a total of 100 scans were averaged to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. Follow-up scans were automatically conducted in the same location during each visit, and the scan position was verified before comparing the sequential images.

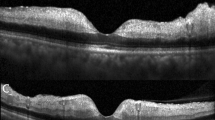

The retinal and choroidal thickness measurements were manually conducted by two graders (D.J.M, I.H.C) using the built-in calipers of the OCT system software (Fig. 1). The graders remained blinded to the patients' identities and the specific times of their visits. The central foveal thickness (CFT) was manually calculated as the distance between the inner surface of the retina and the outer border of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) at the central fovea. Additionally, the central choroid thickness (CCT) was measured as the space between the outer portion of the hyperreflective line corresponding to the RPE layer and the chorioscleral junction. To measure retinal thickness in CRAO eyes, a spot located 1000 um temporally from the fovea was selected. The inner retinal layer (IRL) comprises the ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, and outer plexiform layer. The outer retinal layer (ORL) consists of the remaining layers in the outer retina till the RPE.

The image outlines the regions of interest for measuring retinal layer thickness on enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) scans of an eye with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). These measurements were manually conducted using OCT software. Central foveal thickness (CFT) and central choroid thickness (CCT) were assessed, with CFT representing the distance between the inner retinal surface and the outer border of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) at the central fovea, and CCT indicating the space between the outer portion of the hyperreflective line corresponding to the RPE layer and the chorioscleral junction. The inner retinal layer (IRL) includes the ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, and outer plexiform layer, while the outer retinal layer (ORL) comprises the remaining layers until the RPE. Thickness measurements of ORL and IRL were conducted 1000 μm temporal to the fovea.

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Visual acuity measurements were standardized by converting them to the logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) for all analyses. The primary efficacy outcomes assessed in HBOT included changes in BCVA and OCT features from baseline to month 6. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post hoc analysis, was employed to analyze the time-course of changes in BCVA and OCT features at each examination throughout the observation period, comparing them to the baseline results. Multiple linear regression models were utilized and aimed to identify independent predictors associated with the BCVA at 6 months post-HBOT treatment. Comparison between the HBOT and control groups involved assessing baseline and outcome variables. The normality of data samples was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If data distributions were normal in both groups, Student's t-test was employed for comparison. Alternatively, if the data were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized. The data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics software version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The significance level for all statistical tests was set at a P-value less than 0.05.

Results

The final analysis included a total of 50 eyes from 50 patients. Among them, 29 patients received treatment with HBOT in addition to the acceptable standard treatment (HBOT group), while 21 patients were treated only with the standard treatment without HBOT (control group). Medical reasons for excluding patients from HBOT treatment, thereby placing them in the control group, included congestive heart failure, recent ear surgery or injury, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The baseline characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex distribution, medical backgrounds, duration of symptoms, initial BCVA, CFT, CCT, ORLT and IRLT. In the HBOT group, the average time from the onset of symptoms to the start of HBOT was 86.69 ± 135.76 h. The HBOT group received a median of 11 days of hyperbaric oxygen treatments (range 2–18 days), and no adverse events were documented in any of the patients.

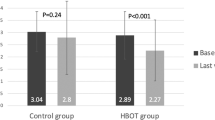

Figure 2 present the VA and OCT outcomes for the HBOT and control groups. HBO-treated patients experienced a significant increase in visual acuity (p < 0.0001). VA demonstrated a consistent and significant improvement with each post-treatment month, consistently surpassing the initial VA (p always < 0.03). In contrast, the visual change in the control group was not statistically significant (p always > 0.1). There were noteworthy reductions in CFT, ORLT, and IRLT (p < 0.0001), with these parameters decreasing significantly with each post-treatment month and consistently being lower than the initial CFT, ORLT, and IRLT (p always < 0.001). The most significant changes in VA, CFT, ORFT and IRLT occurred one month after treatment. CCT increased significantly with each treatment month (p < 0.0001), while there was no significant change in CCT in the control group.

Table 2 presents the mean (± SD) change in BCVA and OCT parameters between the HBOT group and the control group. The VA differs significantly at each post-treatment month, while the CFT and ORLT show significant differences only at the 6-month mark after treatment. The linear regression analysis aimed to identify parameters influencing post-HBOT visual outcomes at 6 months in patients with CRAO (Table 3). The final BCVA exhibited a positive correlation with the initial BCVA, indicating that a higher baseline BCVA is associated with better visual acuity six months after treatment. However, other factors analyzed did not show a significant correlation with the visual outcome at the six-month after treatment.

Discussion

Due to its high oxygen consumption, the retina is particularly susceptible to ischemic damage, leading to irreversible damage to retinal cells after a short period of time2. Vascular recanalization often occurs in retinal vessels after RAO25. Under hyperoxic conditions induced by HBOT, it is noted that the choroid can supply 100% of the oxygen required by the retina, even in cases of retinal artery nonperfusion. Previous studies have reported successful treatment outcomes in eyes suffering from CRAO, which makes HBOT appear to be a promising treatment option for CRAO10,15,16,26. In this study, we conducted functional and structural analyses of the eyes with acute CRAO treated with HBOT, and compared these values between the HBOT treatment group and the non-treatment group.

In the earlier study, the initial HBOT sessions were beneficial and often led to a significant improvement in VA26. Among the parameters we measured post-treatment, significant improvement in VA was observed first. A month after HBOT, VA improvement was observed in fourteen patients (46.67%) and thirteen patients (43.33%) achieved BCVA improvement of more than 0.3 logMAR. These results are consistent with a recent prospective study that reported BCVA improvement of more than 0.3 logMAR was found in 52.6% of CRAO patients after HBOT10. This visual improvement persisted up to 6 months post-treatment, and significant differences were observed compared to the control group throughout the follow-up period. To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared VA results with a control group over a 6-month period following HBOT. Our data demonstrate the effectiveness of HBOT in improving VA in patients with CRAO.

Previous studies investigating OCT findings in eyes with CRAO have consistently shown an initial increase in retinal thickness during the acute phase, followed by a decrease in thickness of the inner retinal layers during follow-up evaluations24,27,28. Our OCT findings align with these previous studies, indicating a significant decrease in retinal layer thickness throughout the follow-up period. However, when we segregated the retinal layers into IRL and ORL and compared their thickness between the treatment and non-treatment groups, we observed no significant difference in IRL thickness. Interestingly, there was a significant difference in ORL thickness. Despite a decrease in ORL thickness observed in the HBOT group, the ORL thickness in this group was significantly thicker than that in the control group. A lesser decrease in ORL thickness suggests the preservation of photoreceptors, which may explain the significant visual recovery observed in the HBOT group.

Outer retinal layer thinning in CRAO is not only associated with vision loss but also with choroidal ischemia, as the choroidal vessels supply the outer retinal layers, including the photoreceptors29. Previous studies using EDI-OCT have shown thinning of the choroid in CRAO24. Choroidal thickness is considered to reflect choroidal blood flow, and choroidal thinning in eyes with CRAO may indicate acute choroidal ischemia, leading to subsequent outer retinal damage and atrophy. However, in the HBOT group, choroidal thickness significantly increased during the follow-up period. These findings suggest that in patients who received HBOT, the less ischemic condition of the choroid may have allowed continuous blood flow to the ORL. This could explain why the ORL thickness was significantly preserved in the HBOT group compared to the control group six months after the procedure.

Although elevated partial pressures of oxygen can cause retinal artery vasoconstriction, it does not reduce oxygen supply when hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is applied12,13,14. Unlike retinal blood flow, choroidal blood flow is not affected by changes in oxygen tension, allowing the significant increase in retinal oxygenation via diffusion from the unaffected choroid. Chiabo J. et al. investigated choroidal thickness a month after HBOT and found no significant difference10. Nejla Tukenmez et al. also examined retinal and choroidal thickness and found that despite a significant decrease in retinal thickness, there was no significant difference in choroidal thickness after HBOT in healthy eyes30. Although there was no statistical difference, choroidal thickness in the nasal area increased. Due to the complex autoregulation system of the retina and choroid31, it is difficult to explain why the choroid thickened after HBOT. However, according to previous studies and our findings, preserved or increased choroidal thickness is associated with preserved or increased choroidal blood flow, potentially preventing outer retinal layer thinning.

Given the significance of choroid function in HBOT, our initial hypothesis posited that a greater CCT might serve as a favorable prognostic factor. This was based on the assumption that increased CCT could enhance oxygen diffusion through the choroidal vasculature. However, the CCT measured on EDI-OCT was not associated with a better visual prognosis in our study. Additionally, other OCT parameters we measured were not associated with visual prognosis either. While several previous studies have indicated that the duration between the onset of initial symptoms and the commencement of HBOT correlates with an improvement in BCVA17,32, our study did not observe this association. The visual prognosis of our patients was solely associated with baseline BCVA. These results are consistent with a recent prospective study10, which also did not find any correlation between OCT parameters, even when including OCT angiography.

It is important to acknowledge that the retrospective nature and the small number of patients in this study are major limitations, which reduce the validity and quality of our results. These limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. Retrospective matching can introduce selection biases, among other limitations. The reasons for patients declining or not receiving hyperbaric oxygen treatment do not appear to be directly related to the pattern or severity of CRAO. Nevertheless, allocation bias might still exist. For example, congestive heart failure in patients who were ineligible for hyperbaric oxygen treatment could have negatively impacted the recovery of retinal perfusion. Additionally, due to the small number of patients, there may be discrepancies between our study and previous studies regarding choroidal thickness, and we were unable to identify associations between visual prognosis and OCT parameters. A previous study detected choroidal thinning in patients categorized as having total CRAO24. Given the small sample size in our study and the fact that nearly all our patients exhibited total CRAO, our results aligned with these previous findings. We suggested that choroidal thinning might be caused by choroidal ischemia, but since we did not perform indocyanine green angiography, we could not provide definitive evidence for this.

There is limited research on the effects of HBOT on the posterior segment of the eye. Gaining insights into how the retina reacts to environmental and physical changes could greatly enhance the development of effective diagnostic and treatment strategies. From this perspective, analyzing OCT images of the contralateral eye would have been beneficial, but we were unable to do so due to a lack of available data. However, our study is the first to compare OCT parameters after HBOT with a control group, revealing significant preservation of the choroid and outer retinal layer compared to the control group. This preservation may contribute to the significant visual recovery observed in HBOT-treated patients.

Data availability

Data is not publicly available due to ethical reasons. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Hayreh, S. S. Acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 30(5), 359–394 (2011).

Brown, G. C. & Magargal, L. E. Central retinal artery obstruction and visual acuity. Ophthalmology 89(1), 14–19 (1982).

Leavitt, J. A., Larson, T. A., Hodge, D. O. & Gullerud, R. E. The incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in Olmsted County Minnesota. Am. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.005 (2011).

Hayreh, S. S. & Zimmerman, M. B. Central retinal artery occlusion: visual outcome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.038 (2005).

Mueller, A. J., Neubauer, A. S., Schaller, U. & Kampik, A. Evaluation of minimally invasive therapies and rationale for a prospective randomized trial to evaluate selective intra-arterial lysis for clinically complete central retinal artery occlusion. Arch. Ophthal. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.121.10.1377 (2003).

Duxbury, O., Bhogal, P., Cloud, G. & Madigan, J. Successful treatment of central retinal artery thromboembolism with ocular massage and intravenous acetazolamide. Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-207943 (2014).

Schumacher, M. et al. Central retinal artery occlusion: local intra-arterial fibrinolysis versus conservative treatment, a multicenter randomized trial. Ophthalmology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.061 (2010).

Garcia-Arumi, J., Martinez-Castillo, V., Boixadera, A., Fonollosa, A. & Corcostegui, B. Surgical embolus removal in retinal artery occlusion. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90(10), 1252–1255 (2006).

Takata, Y., Nitta, Y., Miyakoshi, A. & Hayashi, A. Retinal endovascular surgery with tissue plasminogen activator injection for central retinal artery occlusion. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 9(2), 327–332 (2018).

Chiabo, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of hyperbaric oxygen therapy monitored by fluorescein angiography in patients with retinal artery occlusion. Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2023-323972 (2023).

Piantadosi, C. Physiology of hyperbaric hyperoxia. Respir. Care Clin. N Am. 5(1), 7–19 (1999).

Carlisle, R., Lanphier, E. & Rahn, H. Hyperbaric oxygen and persistence of vision in retinal ischemia. J. Appl. Physiol. 19(5), 914–918 (1964).

Jampol, L. Oxygen therapy and intraocular oxygenation. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 85, 407 (1987).

Landers, M. 3rd. Retinal oxygenation via the choroidal circulation. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 76, 528 (1978).

Menzel-Severing, J. et al. Early hyperbaric oxygen treatment for nonarteritic central retinal artery obstruction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.009 (2012).

Murphy-Lavoie, H., Butler, F. & Hagan, C. Central retinal artery occlusion treated with oxygen: A literature review and treatment algorithm. Undersea Hyperbaric Med. 39(5), 943 (2012).

Ilbasmis, S. & Ercan, E. Long-term evaluation of retinal artery occlusion patients who applied hyperbaric oxygen treatment. J. Health Sci. 6, 148–152 (2018).

Rosignoli, L. et al. The effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in patients with central retinal artery occlusion: A retrospective study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Korean J. Ophthalmol. KJO. 36(2), 108 (2022).

Huang, D. et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science 254(5035), 1178–1181 (1991).

Spaide, R. F., Koizumi, H. & Pozonni, M. C. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 146(4), 496–500 (2008).

Huang, Y.-T. et al. Optical coherence tomography biomarkers in predicting treatment outcomes of diabetic macular edema after dexamethasone implants. Front. Med. 9, 852022 (2022).

Vujosevic, S. et al. Standardization of optical coherence tomography angiography imaging biomarkers in diabetic retinal disease. Ophthal. Res. 64(6), 871–887 (2021).

de Sisternes, L., Simon, N., Tibshirani, R., Leng, T. & Rubin, D. L. Quantitative SD-OCT imaging biomarkers as indicators of age-related macular degeneration progression. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55(11), 7093–7103 (2014).

Ahn, S. J. et al. Retinal and choroidal changes and visual outcome in central retinal artery occlusion: an optical coherence tomography study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.001 (2015).

David, N. J., Norton, E. W., Gass, J. D. & Beauchamp, J. Fluorescein angiography in central retinal artery occlusion. Arch. Ophthal. 77(5), 619–629 (1967).

Schmidt, I. et al. Development of visual acuity under hyperbaric oxygen treatment (HBO) in non arteritic retinal branch artery occlusion. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 258, 303–310 (2020).

Chen, S.-N., Hwang, J.-F. & Chen, Y.-T. Macular thickness measurements in central retinal artery occlusion by optical coherence tomography. Retina 31(4), 730–737 (2011).

Ikeda, F. & Kishi, S. Inner neural retina loss in central retinal artery occlusion. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 54, 423–429 (2010).

Vance, S. K., Imamura, Y. & Freund, K. B. The effects of sildenafil citrate on choroidal thickness as determined by enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Retina 31(2), 332–335 (2011).

Dikmen, N. T. et al. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on retina, choroidal thickness, and choroidal vascularity index. Photodiagnosis. Photodyn. Ther. 38, 102854 (2022).

Linsenmeier, R. A. & Zhang, H. F. Retinal oxygen: from animals to humans. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 58, 115–151 (2017).

Elder, M. J., Rawstron, J. A. & Davis, M. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of acute retinal artery occlusion. Diving Hyperb. Med. 47(4), 233 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions Study design and concept (IHH, SJW); database search (JML), data extracting (SHC), data analysis (GSJ, IBC), manuscript writing (JML, IHH), manuscript revising (JML, SHC, GSJ, IBC, SJW, IHH). All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Statement of Ethics This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved Institutional Review Board/ Ethics Committee Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB no. 2024-03-006). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all parent of participants after explain the nature course. Consent to Publication statement Informed consent was obtained in writing from all parent of participants after explain the nature course. State of data availability Data is not publicly available due to ethical reasons. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Disclosure Statement (Conflicts of Interest). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare Funding Sources Grant: None Funding/Support: None Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures to report

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design and concept (IHH, SJW); database search (JML), data extracting (SHC), data analysis (GSJ, IBC), manuscript writing (JML, IHH), manuscript revising (JML, SHC, GSJ, IBC, SJW, IHH). All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved Institutional Review Board/ Ethics Committee Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB no. 2024-03-006). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all parent of participants after explain the nature course.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.M., Choi, S.H., Jeon, G.S. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in non-arteritic central retinal artery occlusion using enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep 14, 23676 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71895-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71895-1