Abstract

This paper discusses the design process toward new lumped chaotic systems that originates in higher-order ordinary differential equations commonly used as description of ideal oscillators. In investigated third-order case, two chaotic oscillators were constructed. These systems are dual in the sense of vector field geometry local to fixed points. The existence of robust chaos was proved by both standard routines of numerical analysis and practical measurement. For the fourth-order oscillatory equation, the concept based on interaction between superinductor and supercapacitor was examined in detail. Since both “superelements” are active, the nonlinearity essential to the evolution of chaos is fully passive. It is demonstrated that complex motion is robust and does not represent long transient behavior or numerical artefact. The existence of chaos was verified using standard quantifiers of the flow, such as the largest Lyapunov exponents, recurrence plots, approximate entropy and sensitivity calculation. A good final agreement between theoretical assumptions and practical results will be concluded, on a visual comparison basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Harmonic oscillators belong to the most common building blocks in signal processing systems. Pure, smooth, undistorted sinusoidal signal forms a core engine for other, more complex analog systems such as modulators, mixers, frequency synthesizers, etc. Oscillator´s stability in time and frequency domain are key factors for robustness and reliability of radiofrequency communication systems. From a mathematical point of view, sinusoidal oscillators are quasi-linear autonomous deterministic dynamical systems with at least two degrees of freedom. From a practical perspective, analog lumped circuit is designed such that conditions for stable oscillations working regime is satisfied only for predefined singular frequency. Because of linearity, derivation (integration) processes can be modeled by operator s (1/s) and these circuits are analyzed using Laplace transform (LT). Oscillation frequency can be derived directly from evaluation of characteristic equation (CE), i.e., polynomial in complex frequency s. Inverse LT can be easily used to show circuit´s time domain response to short impulse, unity step function, etc.

There are different concepts and topologies of sinusoidal oscillator depending on the frequency band for generated waveform. For low frequency and unpretentious applications, RC feedback oscillators probably represent a good choice. These simple structures utilize looped connection of passive ladder RC feedback and frequency independent amplifiers, inverting or noninverting. In the first case, feedback path comprises, for example, cascade connection of three RC low-pass filters or three RC high-pass filters. These filters are commonly denoted as phase shift oscillators. Noninverting amplifier is used, for example, if feedback RC two-port is realized by band-pass or band-reject second-order filter. Sinusoidal oscillators dedicated for high frequency bands are based on resonant LC circuit, where negative resistance compensates losses. Negative resistance is usually implemented as cross-coupled transistor pair, or two transistor connections known as lambda diode. For generation of large amplitudes, negative resistors can be constructed using a single operational amplifier and three resistors1. The slope of this two-terminal circuit element stands negative until operational amplifier saturates. In this sense, several voltages usually represent usable dynamical range, i.e., it is wide enough even for more complicated shapes of final ampere-voltage characteristics.

Sinusoidal oscillators are supposed to generate the same patterns of waveforms in time domain within a long-term stable period. In contrast to this feature, chaotic signal is entropic and there is no fixed time interval where individual time domain pattern is the same. In addition, closed form analytic solution cannot be derived for potentially chaotic dynamical system. Numerous cases where naturally sinusoidal oscillator switch into generation of more complex dynamics have already been reported. For example, paper2 describes Wien bridge oscillator modified only by adding resistor, capacitor, and Chua´s diode within feedback path. Resulting circuit structure is a combination of original and Chua´s oscillator. There, the authors provide only simulation outputs. Replacement of one linear resistor with JFET transistor connected as nonlinear resistor in typical structure of Wien bridge-based oscillators is topic of work3. Both circuit simulations and experimental results are provided. Comprehensive review paper showing many examples of chaotified Wien bridge oscillator is given in paper4. Chaotic behavior of Wien bridge-based oscillator containing fractional-order memristor is described in work5. There, mem-element is applied in feedback path, modifying second-order sinusoidal oscillator into nonlinear dynamical system with mathematical order between two and three. Even simpler structures of RC feedback chaotic oscillators are given in brief paper6, together with basic verification via circuit simulations. Individual structures contain only a single passive nonlinear two-terminal circuit element, with ampere-voltage characteristics close to conventional diode. Authors in paper7 analyze diode coupling of two RC feedback systems known as phase shift oscillators. The existence of chaos is demonstrated by gallery of screenshots coming from laboratory experiments. Chaotic phenomena in phase shift oscillator are discussed also in paper8. There, standard one-transistor self-biasing circuit topology was modified by additional transistor and is powered from single supply DC voltage. This inductorless realization of chaotic lumped oscillator was verified by simulation and real measurement. As mentioned above, RC feedback oscillators can be considered as closed loop of two-ports, frequency dependent passive feedback and active frequency independent amplifier in direct path. This concept can be interchanges by interaction of higher-order passive immittance and active nonlinear resistor. For the case with resistor–capacitor ladder two-terminal immittance, evolution of chaos is described in paper9. The famous Chua´s oscillator and be understood as the same concept, with RLC immittance implementing linear part of vector field10. This very simple chaotic circuit was also the first one where chaos has been confirmed numerically, experimentally as well as on theoretical basis. Conventional single-stage transistor-based sinusoidal oscillators are also subject to chaotic motion if the nonlinear nature of active three-port is considered. Preliminary study of basic topology of Colpitts oscillator is topic of work11, where, among standard components, single voltage controlled nonlinear resistor is supposed. Chaotic phenomena rising in common emitter high frequency Colpitts oscillator is discussed in paper12 where both numerical and experimental results are provided. Two unconventional structures of Colpitts oscillator with coupled inductors and variable resistor are addressed in paper13. Authors provide accurate mathematical models of these situations and show a full gallery of numerical routines to prove that observed complex dynamics represents structurally stable solution. Authors in work14 demonstrate that two Colpitts oscillators weakly coupled by two linear resistors can exhibit hyperchaotic self-oscillations. It is shown that evolved strange attractor is characterized by two positive Lyapunov exponents (LE). This means that the system exhibits unique features of very high complexity of motion together with low time predictability; and this can be handy in many practical applications of chaotic system. By adding one transistor and single capacitor one can obtain a two-stage Colpitts oscillator. Under specific working conditions, this modification can generate chaotic waveform with “better chaotic fingerprints” than single-stage original network. This fact is proved in paper15. By substituting inductor with series resonant circuit Colpitts oscillator changes into the so-called Clapp oscillator. If all accumulation elements have similar normalized numerical values, this circuit structure can also be chaotified. For hypothetical bias point of bipolar transistor, this situation is described in paper16. Required nonlinearity is introduced by forward trans-conductance, which has odd-symmetrical cubic polynomial form. The so-called Hartley oscillator rises after mutual change of inductors and capacitors in Colpitts structure. Chaos was discovered in this case as well, consult paper17 for more details. Contribution18 shows extremely simple network structure closely related to Hartley oscillator that is still able to generate chaos. Of course, the provided list of publications dealing with chaotic behavior of naturally sinusoidal oscillator is by no means complete. Research focused on chaos localization within mathematical model of analog signal processing block continues, and intensity of these investigations even rises with advances with increasing computational capabilities of personal computers. Curious readers can find many examples of analog systems where robust chaos were detected in paper19.

Besides autonomous chaotic systems, chaos can be observed within internal dynamics of systems excited by periodic forcing. A necessary condition for this kind of behavior is the presence of nonlinearity and, at least, two degrees of freedom. The first studies are dated from almost twenty years ago. From the beginning, driven chaos was analyzed from theoretical as well as practical viewpoint. For example, authors in paper20 focus to find the simplest mathematical model of second order chaotic system perturbed by periodical external force. There, it is pointed out that optimal frequency needs to be used to maximize LE. Paper21 presents searching for a three-dimensional driven system with periodic disturbances, leading to either chaos or bursting oscillations. Paper22 brings a mature study of suppressive impulsive forcing applied on Duffing oscillator. Finally, author in work23 showed that conventional analog circuits with periodic sinusoidal input signal such as frequency filters are also subject to robust chaotic dynamics. Of course, many relevant works can be mentioned here.

Switching back to autonomous systems, Chua´s oscillator inspires researchers and design engineers to construct simple chaotic systems with nonlinearity introduced fully passive circuit element. Nice example of such approach is demonstrated in work24 where second order immittance known as frequency dependent negative resistor (FDNR) is utilized as the only active device. Paper25 shows that a pair of FDNRs nonlinearly coupled by generalized bipolar transistor can generate weakly hyperchaotic waveforms. There, both numerical analysis and laboratory experiments validate this idea, leading to good agreement between expectations and reality. Authors in preliminary study26 show that chaos can be induced in sinusoidal oscillator simply by adding second order diode-inductor composite. This interesting discovery leads to pronunciation of systematic design procedure, that includes also other composites, such as FET-capacitor27,28. Both simulation and experimental results are provided, designed chaotic oscillators are very simple, suitable for home-made construction. As follows from papers20,21,22,23,24 and many others, second-order immittance two-terminals are well-established elements in design process toward chaotic oscillators. However, for design of fourth- and higher-order hyperjerk functions29,30,31,32 with potential chaotic solution, several FDNRs or combination of FDNR with other dynamic circuit element need to be utilized. Thus, complexity of final circuit as well as number of active elements increases. To solve this issue, new versatile topologies of active linear two-terminals described by simple arbitrary-order (up to let’s say sixth order) immittance function in Laplace transform become sought after. Especially those function with simple relations between circuit component values and coefficients of polynomial of full immittance function are welcomed.

This paper is organized as follows. The upcoming section studies several different forms of CE from the viewpoint of possible nonzero oscillating solution of the circuit. Possible circuit structures up to fourth order are considered linear and corresponding oscillation frequency is calculated. The third section describes derivation process toward chaotic systems that are directly related to prototypes of sinusoidal oscillators. Two chaotic systems are analyzed in detail, showing robustness of chaotic steady state. The fourth section is focused on thorough numerical analysis of discovered chaotic oscillators. Standard numerical routines based on numerical integration process have been adopted, such as spectrum of Lyapunov exponents (LE), bifurcation diagrams, signal entropy, recurrence plots, basins of attraction, etc. Next section deals with practical construction of lumped chaotic oscillator, based on findings in theoretical part of this paper. Designed examples are verified in frame of sixth section. It is demonstrated that duality principle allows us to design different circuit topologies with the same global dynamical behavior. Finally, some concluding remarks are provided, along with future possible research directions.

Analysis of quasi-linear circuit

Fundamental configuration of ideal sinusoidal oscillator consists of parallel connection of inductor and capacitor. In practice, both accumulation elements exhibit some losses, and this fact can be modeled by additional parallel resistance. Doing so, under zero initial conditions, single second order ordinary differential equation (ODE) of this network and associated oscillation frequency for infinite value of parallel resistor can be expressed as

Suppose following “typical” values of passive circuit components: resistor in hundreds of kΩ, inductor in units of mH and capacitor in units of nF. Then, oscillation frequency lies within MHz band and time constant is in microseconds, which can be impractical for numerical analysis. Mathematical models in upcoming paper sections will be considered normalized with respect to both angular frequency ωres (reciprocal to time) and impedance ξres. This can be done by substitution

where small letters represent normalized values of passive circuit components, applied on ODE (1). For example, choice of values \({\xi }_{res}\sim {10}^{5}\) and \({\omega }_{res}\sim {10}^{6}\) lowers oscillation frequency to 1 rad/s and increases time constant to seconds. In this short example, resistor has large but finite value. Thus, oscillations will be exponentially dumped (quite slowly). Of course, starting amplitude depends on the initial conditions.

For zero initial conditions, higher order ODE can be transformed into CE polynomial in two steps: Firstly, substitution of complex frequency symbol s instead of time derivative, such that k-th time derivative turns into k-th power of s. Secondly, the resulting equation is divided by main state variable v, leading to polynomial in s. Order of CE is equal to the highest derivative of state variable v in original ODE. Of course, the second order dynamical system cannot exhibit complex, random-like motion known as chaos. It is because exponential divergence of neighboring orbits and boundedness of attractor cannot be created in systems with only two degrees of freedom. Two state trajectories cannot cross each other since different future evolution in deterministic system is forbidden. Therefore, higher-order CE should be considered as the starting equation for the design of chaotic oscillator.

Let suppose the most general form of ODE associated with third-order dynamical system, that is

where the state variable marked as x is either voltage or current depending on structure of circuit. Obviously, this ODE contains ideal oscillation system (1) under assumption \(\beta =0, \delta =0\). Straightforward analysis yields following condition for stable oscillation and corresponding oscillation frequency

There exists a special case of third-order system that is still capable of generating steady state sinusoidal signal, namely for \(\gamma =0, \varepsilon =0\) we get oscillation frequency \(\omega =\sqrt{\delta /\beta }\).

Now, let’s turn our attention to fourth-order dynamical systems. For starters, let’s suppose the most general fourth-order oscillatory equations associated with quasilinear autonomous circuit. It can be expressed as

where x is some circuit quantity. Assume zero initial conditions and all coefficients \(\left\{\alpha , \beta , \gamma , \delta , \varepsilon \right\}\) real positive numbers. This leads to following oscillation frequency and condition for stable oscillation

Sinusoidal steady state signal is solution of fourth-order oscillatory equations also in the case of reduction of some terms, such as

or

In the case

Oscillation frequency can be calculated as positive real value coming from following formula

Note that fourth-order dynamical systems described by ODE (7), (8) and (9) do not involve formula that specifies condition for stable oscillation. These systems work in self-oscillating steady state automatically. For single ODE having only odd time derivatives of leading state variable, the situation is the same and system can generate stable unconditioned oscillations. Note that this is only hypothetical case; in practical application, some amplitude stabilization mechanism will be necessary.

For higher-order linear ODE, conditions for stable oscillations and corresponding frequency of oscillation can be obtained analogically. Suppose that our circuit is fully passive, i.e., contains only resistors, capacitors and inductors. Then, corresponding CE will have only positive real coefficients and time-domain response to time-limited excitation force will be always exponentially damped.

Nonlinear circuit analysis

In this section, single higher-order ODE will be addressed with respect to evolution of chaotic dynamics. Analysis of nonlinear jerk functions based on harmonic balance method is presented in paper33. Using this analytic approach, periodic solutions can be found. This paper section is dedicated to synthesis of chaotic oscillators based on ideal oscillating network of the same mathematical order. Basic idea behind this transformation is to include simple three segment odd-symmetrical piecewise linear (PWL) scalar function into oscillating circuit. In an upcoming text, two third order and two fourth order chaotic systems will be addressed. For individual cases, as part of this section, stability analysis necessary for revealing the so-called self-excited chaotic attractors is provided.

It is well known that single third-order ODE with scalar polynomial nonlinearity belongs to the simplest mathematical model able to generate robust chaotic behavior34,35. Algebraical simplicity predetermines these dynamical systems for numerical algorithms capable of localizing chaotic motion within lower-dimensional hyperspace of internal system parameters36,37,38. For example, assume following concrete form of ODE that describes first Kirchhoff law of some lumped circuit

where parameter γ has units in F⋅s, parameter δ represents standard capacity in F, v is the main nodal voltage and PWL function is

where Vbreak stands for breakpoint voltage and gout is differential transconductance in outer segments of PWL function (slope in inner segment is zero). Note that expression (11) is closely related to linear ODE (3). The vector field of analyzed dynamical system exhibits three affine segments where analytic closed-form solution can be found. Namely, for inner region of vector field we have state equations

and in both outer regions of vector field where either v < –Vbreak or v > Vbreak

Individual state matrices represent Jacobi matrices simultaneously. Dynamical system (11) with nonlinearity (12) possesses three fixed points, one is always placed in origin of state space and two mirrored equilibrium points located in positions

Parameter β can be fixed unity and, in the case of circuit realization of dynamical system, it has the meaning of scaling parameter. Note that eigenvalues in inner segments are defined by ε while eigenvalues in both outer segments are calculated by sum ε + gout. Based on slopes of PWL resistor in individual segments, two different cases can be described. Let denote variant with plus sign in (11) as case A and system with minus sign as case B. Circuit realization of function (12) for case A and case B is visualized in Figs. 2 and 3 respectively (region labeled as PWL resistor). We experience chaos for following default choice of vector field \(\dot{\mathbf{v}}={\varvec{\Psi}}\left(\mathbf{v}\right)\)

Note that both systems are dissipative with the same volume contraction coefficient γ providing fundamental limit cycles that evolve in different places in vector field. For numerical values (16) and case A system, we have eigenvalues associated with fixed point at origin λ1,2 = –0.594 ± j1.16, λ3 = 0.588 and in both outer segments of vector field we have two mirrored fixed points characterized by eigenvalues λ1,2 = 0.329 ± j1.31, λ3 = –1.258. For case B dynamical system, we have fixed point located at origin of state space with associated eigenvalues λ1,2 = 0.118 ± j1.088, λ3 = –0.836 while equilibria in outer segments exhibit saddle-spiral movement with “the opposite stability index”, namely eigenvalues λ1,2 = –0.77 ± j1.362, λ3 = 0.94.

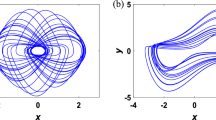

Figure 1 is graphical demonstration how state attractor varies with change of coefficients ε and gout. Starting with ε = –1 S and gout = 3.3 S we are experiencing chaotic attractors for both cases of analyzed dynamical systems. Case A possesses local vector field geometry in all segments of vector field typical for famous double-scroll attractor39,40, i.e., unstable spiral in both outer segments. A final strange attractor visits all segments of vector field and can be considered as two spirals merged. The chaotic attractor of case B system is like the so-called dual double-scroll attractor41, that is geometry decomposition ℜ3 = ℜunstable1 ⊕ ℜstable2 in both outer and ℜ3 = ℜunstable2 ⊕ ℜstable1 in inner segment of vector field respectively. Now let’s focus on what happens if parameter gout will be decreased. Case B starts to generate limit cycle for values gout < 2.7 S without local bifurcations of fixed points. Within interesting range of parameter ε ∈ (3.2, 1.5) S, case A system exhibits gallery of chaotic attractors interrupted by periodic windows, and complex behavior finally ends with pure imaginary eigenvalues that corresponds to two mirrored limit cycles as show in Fig. 1g. If parameter gout is decreased below threshold value gout = 1.6, outer fixed points become stable, see Fig. 1h. For trajectories given in Fig. 1a to h initial conditions were chosen as x0 = (± 0.1, 0, 0)T. Combinations of pairs ε, gout for Fig. 1a to q) are following: {–1, 3.3} S, {–1, 2.8} S, {–1, 2.7} S, {–1, 2.1} S, {–1, 2} S, {–1, 1.7} S, {–1, 1.6} S, {–1, 1.5} S, and {–0.5, 3.3} S, {–0.6, 3.3} S, {–0.7, 3.3} S, {–1.2, 3.3} S, {–1.6, 3.3} S, {–2.3, 3.3} S, {–2.51, 3.3} S, {–2.7, 3.3} S, {–2.8, 3.3} S. Some evolved attractors are put into context of eigenvalues in individual segments of vector field. Figure 1 provides insight into what is called sensitive dependance on initial conditions. Group of 104 initial conditions are randomly spread (using uniform distribution, cube with edge 0.1) around origin of state space. Then, final states after short time evolution 1 s (red points), 10 s medium time (green points) and longtime evolution 100 s (blue dots) are stored and visualized. It is obvious that in the latter case full geometric shape of strange attractor is revealed, for both cases A and B.

Attractor evolution with respect to parameters: (a)–(q), axis system is included. Orange orbits represent case A system, blue trajectories correspond to case B dynamical systems, grey planes are boundaries between individual affine state space segments and black dots denote fixed points. Sensitivity dependance of solution to small changes in initial conditions: (r) case A and double-scroll, (s) typical chaotic attractor of case B dynamical system, (t) case A and one single scroll attractor, corresponding axis system is provided. More details about individual subplots can be found in the text.

This is the right place to state that, besides double-scroll and dual double-scroll, double-hook42 can be generated (as the most complex strange attractor) by class of three-segment PWL vector field. The difference with famous double-scroll is in geometry of inner segment of vector field, which is composed by three eigenvectors, namely ℜ3 = ℜunstable1 ⊕ ℜstable1 ⊕ ℜstable1. From visual point of view, the difference starts to be obvious after zooming in dynamic motion near origin of state space. However, the necessary bifurcation scenario has not been observed in the case of class A/B dynamical system.

The simplest possible circuit realization of mathematical model (11) with (12) should not be the only feature we are looking for. One-to-one relations between coefficients of ODE and value of resistor also belongs to important circuit property. This is the case of implementation depicted in Fig. 2a. Input admittance of this two-terminal network can be expressed as

where Zk for k = 1, …, 5 are general impedances considered as either resistor or capacitor. Suppose choice of same valued capacitor C as Z1, Z2, capacitor CX as Z5 and resistor RA and RB as impedance Z3 and Z4 respectively. These yields following simplification written in Laplace transform (symbol s represents complex frequency)

Case A third-order autonomous chaotic electronic system: (a) linear third-order two-terminal element with general impedances, (b) circuitry realization, (c) typical chaotic attractor produced by this chaotic oscillator, (d) wideband frequency spectrum of generated signals, (e) kinetic energy distribution over state space, f) rainbow color scale for LE plots. The largest LE as function of PWL resistor shape: (g)–(o) gin ∈ (0.2, 1.4) S, gout ∈ (2, 3.2) S.

Assume this impedance terminated by passive circuit element. Such configuration cannot generate chaos since all coefficients of CE will be positive while its roots are negative, leading to damped oscillations. However, two-terminal (18) is still suitable for implementation of single third-order ODE with chaotic motion if completed (terminated) by single linear negative resistor and passive nonlinear resistor composed by two pairs of conventional diodes. In this sense, passive nonlinearity means that realization contains only resistors and conventional diodes. Real numerical values of final chaotic oscillator can be obtained after application of time and impedance denormalization. By adopting time norm τ = 100 μs and impedance norm ξ = 103 we obtain numerical values of circuit components provided by means of final schematic in Fig. 2b. Based on this interconnection, following ODE can be derived for case A chaotic oscillator

where VT is threshold voltage of forward biased diode (about 750 mV for single BAT 18 diode). Similarly for case B (Fig. 3) we get single third-order ODE of the form

Case B third-order chaotic system, snippets from numerical analysis. Circuit simulation results: (a) practical realization, (b) plane projections of typical strange attractors, (c) frequency spectrum of chaotic signals, (d) kinetic energy distribution over state space plotted as projection in v vs dv/dt plane, (e) RP for state variable d2v/dt2, (f) possibility for attractor’s size rescaling using breakpoints of PWL function: Vbp = 700 mV (blue curve), Vbp = 1 V (orange attractor) and Vbp = 1.3 V (green attractor), (g) PS (black dots) visualized in v vs dv/dt plane.

Note that each circuit is very simple, suitable for practical demonstrations and educational purposes, and contains only two operational amplifiers. Figure 2c shows transient circuit simulation of developed chaotic oscillator using Orcad Pspice software. Final time was set to 300 ms with maximum time step 1 μs. By considering the same waveforms, their transformations into frequency domain are provided in Fig. 2d. Figure 2 also illustrates direct computer-aided analysis of mathematical model (11) with nonlinear function (12), namely case A. For example, Fig. 2e shows rainbow scaled distributions of dynamic energy visualized in plane d2v/dt2 = 0 for ε = –1 and two cases: gout = 1.6 (mirrored limit cycles) and gout = 2.7 (merged strange attractor). There is a visible drop of energy between segments of vector field, but it is not the main reason for chaos disappearance. Both ε and gout can be used as natural bifurcation parameters. It is proved via calculation of the largest LE as two-dimensional function of these parameters in range ε ∈ (0.2, 1.4) S, gout ∈ (2, 3.2) S and plotted as high-resolution surface-contour graphs. Rainbow inspired color scale is specified in Fig. 2f, while individual 101 × 101 = 10,201 valued plots are provided as Fig. 2g–o. Areas leading to chaotic behavior are wide, such that robust chaotic oscillator can be constructed as lumped electronic circuit. The largest LE is about 0.232 leading to Kaplan-Yorke dimension 2.28. Maximizing the largest LE was done by nature-inspired optimization technique43,44. During this numerical investigation, initial conditions were kept as x0 = (0.1, 0, 0)T. Since numerical values of eigenvalues are known, optimal time step for numerical integration process can be chosen45. LE are calculated with parameters that guarantee accuracy of dynamical flow classification46,47.

From the circuit realization point of view, negative resistor is supposed to work in linear regime such that diode-resistor composite represents the only nonlinearity. Series connection of two diodes is utilized to increase breakpoint voltage in (11) and enlarge an evolved strange attractor. If a small-sized pattern is required, two single diodes should be used. If diode threshold voltage is about 150 mV, double-scroll attractor occupies very small volume of state space (cube with edge smaller than 500 mV centered around state space origin). This could be welcomed for practical applications where small power supply voltage is necessary.

Figure 3 briefly uncovers dynamical features system (11) class B. Starting with intuitive circuit realization in Fig. 3a plane projections of typical strange attractors are provided in Fig. 3b and frequency spectra of generated waveforms are visualized in Fig. 3c. Obviously, circuit realization consists of parallel connection of linear third-order two-terminal element (15), resistor R3 and negative resistor R2. The latter case will be active only for input voltages above or below constant threshold voltages given as two times voltage drop across BAT18 silicon diode. Kinetic energy distribution, understood in the same sense as in Fig. 2e, is shown in Fig. 3d. Again, places with high energy are red; lowering energy goes through yellow, green and ending with very low energy areas marked by magenta color. One example of recurrence plot and attractor rescaling property is demonstrated via Fig. 3e and f respectively. Recurrence plot (RP) shows similarity of signal patterns, in our case, for 1000 s long time sequence. If different segments of state trajectories come closer than 0.01, point is stored. The upper subplot of RP clearly shows systematic pattern of periodic behavior. On the other hand, the lower subplot reveals randomness of truly chaotic waveform. Figure 3f demonstrate proportionality of strange attractor size and value of breakpoint of PWL function. It means that volume occupied by desired attractor can be decreased by using diode with low forward drop voltage. Figure 3g is visualization of Poincaré sections (PS) associated with typical chaotic attractor generated by class B third-order dynamical system. From left to right, individual cross sections are given by formulas: v = 0 V, v = ± 1 V, dv/dt = 0 V/s, d2v/dt2 = 0 (V/s)2, and d2v/dt2 = ± 1 (V/s)2. For this numerical investigation, final time was set to 1000 s with time step 1 ms.

Four state variables are needed to observe hyperchaotic self-oscillations. Obviously, the corresponding single ODE description will be of fourth order. However, some of its coefficients can be zero. Suppose parallel connection of FDNR (element primarily developed for inductorless active filter design after application of Bruton transformation), super-inductor and resistor. Under zero initial conditions, this simple interconnection can be described by following CE in Laplace transform

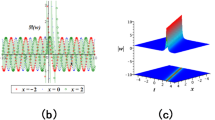

where s is complex radian frequency (jω), parameters D and E represent super-capacity in F⋅s and super-inductance (F⋅s)–1 respectively. This is the right place to rename FDNR as super-capacity (SPC) since super-inductance (SPI) is, in fact, also frequency dependent negative resistor. The only difference is that module of impedance of SPC decreases with square of angular frequency while module of impedance of SPI increases with angular frequency squared. Phase shift for both SPC and SPI is the same, namely 180 degrees. Because of the relation between Laplace transform and linear ODE with constant coefficients (and simple solution of ODE through tabularized inverse Laplace transform), both SPI and SPC can be used as building blocks for circuit synthesis. Following relations between time domain and frequency domain description of linear SPC and SPI was adopted in upcoming text

Suppose simple interconnection of circuit elements visualized in Fig. 4a. Describing ODE can be derived easily based on first Kirchhoff´s law saying that iE + iD + iN = 0. Single fourth-order ODE with scalar PWL function in the form of admittance (is valid in each segment of vector field) can be expressed as

where voltage represents the main state variable and PWL function can be expressed as

where Vbreak are breakpoint voltages, gout and gin are admittances in outer and inner segment of PWL function respectively. Let introduce state vector

where vD is voltage across SPC and iE stands for current flowing through SPI respectively. Then, matrix expression of set of ODE becomes

Novel network concepts of fourth-order autonomous deterministic chaotic oscillators: (a) parallel connection of dual super-elements and fully passive nonlinear resistor, (b) real circuit implementation of this kind of circuit with three-segment PWL resistor, (c) flow-equivalent realization of fourth-order dynamical system (24), (d) analog computer-based construction of flow-equivalent oscillating circuit by following duality principle.

Dynamical system (19) possesses only one fixed point located at origin of state space. Symbolic formulas for eigenvalues are following

where J is linearization matrix in vicinity of state space origin and E is unity matrix. Chaos can be observed for simple choice

leading to interaction of stable and unstable spiral movement within inner region of vector field, and this dynamic is governed by following eigenvalues

Straightforward practical realization of this kind of self-oscillating circuit is provided in Fig. 4b. This chaotic system is composed of parallel connection of SPC (subcircuit with R1, R2, R3, C1, C2), block SPI (part with R4, R5, R6, C3, C4) and passive nonlinear resistor. Since time constants in second as well as currents in amperes are not practical for both implementation and measurement, rescaling of values of passive circuit elements needs to be applied. Numerical values provided in the final schematic deal with time and impedance scaling factor 10–3 and 103 respectively. Note that only one integrated circuit is required; TL084 comprises four operational amplifiers in one package.

Alternative design technique is based on integrator black schematic of dynamical system and its example is given in Fig. 4c. This is a favorite design method among electrical engineers because of its universality but, on the other hand, final circuit can be very complicated with many active devices48,49. Dynamical behavior of designed circuit is uniquely determined by following set of first-order ODE.

where iD = 0 A in inner segment and iD = vx/(R7 + RD) in both outer segments of vector field. Note that mathematical model (30) is slightly different than original expression (26). However, system (30) can be obtained from (26) by application of trivial transformation of coordinates, namely inverse of the last state variable. Doing so, dynamical phenomena remain unchanged.

Thanks to duality principle, chaos can be generated by circuitry depicted in Fig. 4d where series combination of SPC, SPI and nonlinear resistor is proposed. Behavior of this dynamical system in each linear segment of vector field is uniquely determined by following ODE

where three segment PWL function is

where Ibreak are breakpoint currents. Note that ODE (31) is the same as (23) after interchange of “dual circuit-oriented symbols”. Therefore, its linear analysis is analogical. Duality principle is a handy tool also for nonlinear circuit analysis since time domain solution of dual systems is formally the same. It follows from matrix expression of circuit given in Fig. 4d, that is

Symbolic formulas for eigenvalues are following

Circuit realization of dual chaotic oscillator is analogical to original system. SPI and SPC can be grounded and therefore implemented by the same blocks as in Fig. 4b. Fourth-order dynamical system (33) can be preferred over (26) if floating PWL resistor turns to be more convenient for practical experiments. Note that mathematical expression (33) directly represents the so-called hyperjerk function, i.e., has connection to classical mechanics. To observe chaos, normalized values of admittances are the same as impedances, that is rout = 3 Ω and rin = 0 Ω.

Now we can mention the main advantage of the proposed design method over the widely preferred analog computer concept. Subcircuit given in Fig. 2a can be reused as grounded two-terminal in place of impedance Z5 such that fourth and higher order hyperjerk functions can be easily implemented. Considering only capacitors as accumulation elements, fifth-order hyperjerk systems can be implemented using only two operational amplifiers. Secondary, relations between math model parameters and circuit component values remain very simple.

Numerical results for fourth-order systems

Upcoming numerical results have been obtained for dimensionless mathematical model while considering normalized value of super-inductance E = 1 (F·s)–1 and super-capacitance D = 1 F·s. For numerical integration process, which forms key part for all kinds of analysis, fourth-order Runge–Kutta method with fixed time step has been utilized. To get a better overview on individual aspects of dynamics and for comparison purposes, all dynamical systems were analyzed using procedures with the same input parameters. Recurrence plots (RP) were calculated for time sequences of all state variables, evolved between 1000 and 2000s, i.e., with transient behavior omitted. Points are stored if enter a neighborhood represented by a sphere with radius 0.05. Approximate entropy (AE) is quantity also calculated from generated signals in time domain50, namely for 1000 s long sequence. For dual fourth-order dynamical systems, embedded dimension is chosen as four, tolerance of AE was set to 0.2 times standard deviation of first state variable. For RP and AE, initial conditions were x0 = (0.1, 0, 0, 0)T. Positive results in the sense of identified chaotic solution can be obtained using spectral entropy as well51.

Time evolution of system solution and system states can be quantified using different energies. Position energy can be established as distance between system state and origin of state space calculated along state space attractor.

From the viewpoint of chaotic oscillator, an interesting feature is power generation watched over all two-terminal elements presented in circuit. For case B dynamical system, we have

Figure 5 provides a few numerical results associated with dynamical system (25). Besides visualization of typical chaotic attractor, PS for selected plane projections are provided (red points). There, state space is reduced to two by choosing the remaining state variables equal zero. RPs are provided for 1000 samples of all state variables. Significant randomness of generated waveforms is obvious from the non-systematic nature of stored and visualized intersection points. Plots of AE, visualized using rainbow color scale, reveal that parametric regions leading to chaotic motion are wide, maximal calculated value of AE is 0.32 (the reddest point in all plots).

Numerical integration results for fourth-order chaotic system given by ODE (26): (a) typical chaotic attractor visualization in 3D and 2D (geometrical shape is not fully revealed), (b) vD(t) vs dvD(t)/dt, (c) vD(t) vs iE(t), (d) vD(t) vs diE(t)/dt, (e) iE(t) vs diE(t)/dt. RP for individual state waveforms: (f) vD(t), (g) dvD(t)/dt, (h) iE, and (i) diE/dt. Contour plots of AE associated with generated signals calculated with respect to shape of PWL resistor: (j) gin ∈ (–1, 1) S, gout ∈ (3, 7) S.

Figure 6, in fact, contains selected results coming from numerical analysis of dynamical system (30). Besides generated chaotic attractor and its plane projections, sensitivity dependance on small changes of initial conditions is demonstrated. Group of 104 randomly generated initial states was spread with uniform distribution and maximal deviation 0.01 in a close neighborhood of state space origin (black dots). Figure 6b for initial expansion of dynamical flow; red points are stored after 1 s of system evolution, green dots for 2 s and blue points for 3s time evolution. Similarly, Fig. 6c, d shows long time evolution of system states, final states are stored after 10 s (red points), 20 s (green dots) and 50 s (blue points) of system evolution. Note that after 50 s final states are already spread over strange attractors. In frame of this figure, all power issues (35–37) have been calculated and put into context of vD-iE plane projection, see Fig. 6e, f and g. Color scale is chosen such that magenta represents the lowest value and red marks the highest value. Even for high values of position energy state orbits are attracted to state space object with limited volume and do not diverge to infinity. The maximum value of AE for this system is about 0.29 (red areas in all plots).

Numerical integration results for fourth-order chaotic system given by ODE (33): (a) typical chaotic attractor visualization in 3D and 2D, (b) short time evolution of randomly generated system states along chaotic attractor, (c) (d) long time system evolution in visualized from two perspectives. Position energy is provided in (e), power generation of SPC and SPI is in plot (f) and (g) respectively. RP calculated for state variables: (h) vD(t), (i) dvD(t)/dt, (j) iE, and (k) diE/dt. AE of generated signals calculated with respect to PWL resistor slope gin ∈ (–1, 0) S, gout ∈ (7, 11) S.

Experimental results and comparison

This section contains results coming from experimental measurement of designed chaotic oscillators. Figure 7 shows selected plane projections of state attractors obtained as bifurcation sequence while changing value of resistor R2 in Fig. 2b approximately within range from 800 Ω down to 200 Ω. In fact, there are three measurable node voltages in the third-order linear admittance network given in Fig. 2b, namely Va, Vb and Vc. If we denote input voltage as v (our main state variable) these voltages represent

Thus, first and second time derivative of the main state variable v is accessible as linear combination. However, formulas (38) are correct only if an active element close to ideal operational amplifier is involved.

Figure 8 has the same meaning but captured oscilloscope screenshots are associated with case B third-order dynamical system; and resistor R2 in Fig. 3a was supposed as variable circuit parameter (lowering its value from 1 kΩ down to 200 Ω). For both third-order chaotic systems, very good correspondence between numerical analysis and experimental outputs can be concluded. Of course, curious readers can observe and capture the entire period-doubling bifurcation scenario. Interesting bifurcation sequence can be traced via change of resistors R3, i.e., slope of PWL function in inner segment of vector field (this proposition holds for both case A and case B dynamical systems). For case A and B dynamical systems, period doubling bifurcation scenario is expected.

Figure 9 shows measurement results associated with fourth-order chaotic system, namely case given by ODE (26). Captured oscilloscope screenshots demonstrate one-sided transition between periodic orbit into chaotic working regime via change of shape of PWL function. Numerical integration counterparts are assigned to selected chaotic attractors, proving good agreement between theory and experiment (check subplots with the same red symbols in right upper corner). Similarly, as it is for third-order chaotic oscillators, some state variables of original mathematical model are “hidden” inside SPC and SPI blocks. For ideal operational amplifiers involved, accessible node voltages are

from which complete state vector (25) can be reconstructed. In other words, by measuring internal node voltages of SPC and SPI we can gain full idea about shape of generated state space attractor. Time constants of all constructed chaotic oscillators are chosen such that frequency spectrum of generated signals mostly fits audio bandwidth. Thus, the working values of capacitors are high if compared to capacitors that reflect parasitic properties of used active devices52. Operational amplifiers are treated as close to ideal and error terms in describing set of ODE are neglected. If chaotic oscillator is intended for some practical application, the effect of non-ideal properties of active elements to global dynamics need to be investigated.

Captured plane projections of state attractors changing during route-to-chaos scenario. Plane projection vD vs dvD/dt: (a) (b) limit cycle, (c)–(e) chaotic attractor. Plane projection vD vs iE: (f) (g) limit cycle, (h)–(j) chaotic attractor. Plane projection vD vs diE/dt: (k) (l) periodic trajectory, (m)–(o) chaotic attractor. Plane projection dvD/dt vs iE: (p)–(r) limit cycle, (s) (t) chaotic attractor. Plane projection iE vs diE/dt: (u) periodic orbit, (v)–(y) strange attractor.

Conclusion

This paper is a retrospective look at the chaos evolution in jerk functions (higher order derivatives of position in mechanics) and graphical demonstration (via several practical examples) of how chaotic oscillations evolve in naturally sinusoidal oscillators if simple PWL nonlinearity is involved. It is demonstrated that single, nonlinear, eventually passive, and properly placed circuit element can push naturally sinusoidal oscillator into robust chaos generation working regime. Moreover, numerical values of passive circuit components can be established such that chaotic operation is not vulnerable to fabrication tolerances, value shifts or temperature drifts.

Analyzed situations represent non-exceptional cases of autonomous deterministic dynamical systems that exist in nature and artificial environments. The same mathematical descriptions occur not only in analog electrical engineering, but model common phenomena also in mechanics, biology, social, biological models and others.

Content of this work meets standards mentioned in paper53. Analysis of dynamical systems does not rely only on approximate methods (model and circuit simulations) but is supported by true measurement. Smooth integration together with relatively short time constants (if compared with original dimensionless mathematical model) guarantee that chaos represents steady state. There is no need to impose a specific set of initial conditions to reach the desired chaotic attractor.

As part of concluding remarks, future research topics can be mentioned. Some questions that should be answered are following:

-

1.

Is it possible to track evolution of structurally stable hyperchaotic attractors in the case of coupled SPI and SPC? So far, structurally stable hyperchaotic self-oscillations have not been detected.

-

2.

Is it possible to generalize proposed method (termination of higher-order two-terminal immittance function with PWL resistor to observe chaos) for single fractional order ODE? If this question is going to be answered on a true experimental basis, following fact needs to be respected: chaos is wideband signal. Therefore, frequency domain approximation of fractional-order circuit element needs to be wideband as well. More details can be found in paper54.

-

3.

Are there some interestingly shaped strange attractors for chaotic oscillators composed by series–parallel interconnections of single PWL resistor and superelements only? Note that part of this question has been already answered by this paper.

-

4.

Is it possible to transform analyzed dynamical systems and replace operational amplifier-based PWL resistors with single circuit component such as resonant tunneling diode or properly biased transistor?

-

5.

Can some parts of the proposed third and fourth order chaotic oscillators be replaced by memristor55,56 or memelement in general5 while circuit dynamics remain unchanged? Memristor can take function as either nonlinearity combined with inertia or nonlinearity only.

Data availability

Key data is provided within the manuscript. Supplementary data (numerical analysis of mathematical model, computer-aided analysis of chaotic circuits, detailed measurement results) can be shared with readers based on their request using email (addressed to corresponding author).

References

Itoh, M. Synthesis of electronic circuits for simulating nonlinear dynamics. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 11(3), 605–653. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218127401002341 (2001).

Morgul, O. Wien bridge based RC chaos generator. Electron. Lett. 31(24), 2058–2059. https://doi.org/10.1049/EL:19951411 (1995).

Elwakil, A. S. & Kennedy, M. P. A family of Wien-type oscillators modified for chaos. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 25(6), 561–579 (1997).

Kilic, R. & Yildrim, F. A survey of Wien bridge-based chaotic oscillators: design and experimental issues. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 38, 1394–1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2008.02.016 (2008).

Rajagopal, K. et al. Chaotic dynamics of modified Wien bridge oscillator with fractional order memristor. Radioengineering 28(1), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.13164/re.2019.0165 (2019).

Bernat, P. & Balaz, I. RC autonomous circuits with chaotic behavior. Radioengineering 11(2), 1–5 (2002).

Hosokawa, Y., Nishio, Y. & Ushida, A. Analysis of chaotic phenomena in two RC phase shift oscillators coupled by a diode. IEICE Trans. Fundam. E84–A(9), 2288–2295. https://doi.org/10.1109/81.331536 (2001).

Keuninckx, L., Van der Sande, G. & Danckaert, J. Simple two-transistor single-supply resistor-capacitor chaotic oscillator. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 62(9), 891–895. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2015.2435211 (2015).

Ogorzalek, M. J. Order and chaos in a third-order RC ladder network with nonlinear feedback. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 36(9), 1221–1230. https://doi.org/10.1109/31.34668 (1989).

Matsumoto, T. A chaotic attractor from Chua´s circuit. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 31(12), 1055–1058. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCS.1984.1085459 (1984).

Kennedy, M. P. Chaos in the Colpitts oscillator. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 41(11), 771–774. https://doi.org/10.1109/81.331536 (1994).

Wafo Tekam, R. B., Kengne, J. & Kenmoe, G. D. High frequency Colpitts oscillator: a simple configuration for chaos generation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 126, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2019.07.020 (2019).

Kamdoum Tamba, V., Fotsin, H. B., Kengne, J., Kapche Tagne, F. & Talla, P. K. Coupled inductor based chaotic Colpitts oscillators: mathematical modeling and synchronization issues. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 130, 137. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2015-15137-x (2015).

Cernys, A., Tamasevicius, A., Baziliauskas, A., Krivickas, R. & Lindberg, E. Hyperchaos in coupled Colpitts oscillators. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 17, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(02)00373-9 (2003).

Kengne, J., Chedjou, J. C., Fono, V. A. & Kyamakya, K. On the analysis of bipolar transistor based chaotic circuits: case of a two-stage Colpitts oscillator. Nonlinear Dyn. 67, 1247–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-011-0066-7 (2012).

Petrzela, J. Chaotic and hyperchaotic dynamics of a Clapp oscillator. Mathematics 10(11), 1868. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10111868 (2022).

Kvarda, P. Chaos in Hartley´s oscillator. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 12(10), 2229–2232. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218127402005777 (2011).

Tchitnga, R., Fotsin, H. S., Nana, B., Fotso, P. H. L. & Woafo, P. Hartley´s oscillator: The simplest chaotic two-component circuit. Chaos Solitons Fractals 45, 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2011.12.017 (2012).

Petrzela, J. Chaos in analog electronic circuits: Comprehensive review, solved problems, open topics and small example. Mathematics 10(21), 4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10214108 (2022).

Gottlieb, H. P. W. & Sprott, J. C. Simplest driven conservative chaotic oscillator. Phys. Lett. A 29(6), 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(01)00765-4 (2001).

Wang, M., Li, J., Zhang, X., Ho-Ching, Lu. & H., Fernando, T., Li, Z., Zeng, Y.,. A novel non-autonomous chaotic system with infinite 2-D lattice of attractors and bursting oscillations. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 68(3), 1023–1027. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2020.3020816 (2020).

Martinez, P. J., Euzzor, S., Gallas, J. A. C., Meucci, R. & Chacón, R. Identification of minimal parameters for optimal suppression of chaos in dissipative driven systems. Sci. Rep. 7, 17988 (2017).

Petrzela, J. On the existence of chaos in the electronically adjustable structures of the state variable filters. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 44(10), 1779–1797. https://doi.org/10.1002/cta.2193 (2016).

Elwakil, A. S. & Kennedy, M. P. Chaotic oscillator configuration using a frequency dependent negative resistor. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 9(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218126699000190 (1999).

Petrzela, J. Canonical hyperchaotic oscillators with single generalized transistor and generative two-terminal elements. IEEE Access 10, 90456–90466. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3201870 (2022).

Elwakil, A. S. & Kennedy, M. P. Novel chaotic oscillator configuration using a diode-inductor composite. Int. J. Electron. 87(4), 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/002072100132057 (2000).

Elwakil, A. S. & Kennedy, M. P. A semi-systematic procedure for producing chaos from sinusoidal oscillators using diode-inductor and FET-capacitor composites. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 47(4), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1109/81.841862 (2000).

Elwakil, A. S. & Kennedy, M. P. Construction of classes of circuit-independent chaotic oscillators using passive-only nonlinear devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 48(3), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1109/81.915386 (2001).

Chlouverakis, K. E. & Sprottt, J. C. Chaotic hyperjerk systems. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 28(3), 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2005.08.019 (2006).

Leutcho, G. D., Kengne, J. & Kengne, R. Remerging Feigenbaum trees, and multiple coexisting bifurcations in a novel hybrid diode-based hyperjerk circuit with offset boosting. Int. J. Dyn. Control 7, 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-018-0438-7 (2019).

Kengne, J., Folifak Signing, V. R., Chedjou, J. C. & Leutcho, G. D. Nonlinear behavior of a novel chaotic jerk system: antimonotonicity, crises, and multiple coexisting attractors. Int. J. Dyn. Control 6, 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-017-0318-6 (2018).

Fonzin Fonzin, T. et al. On the dynamics of simplified canonical Chua´s oscillator with smooth hyperbolic sine nonlinearity: hyperchaos, multistability and multistability control. Chaos 29, 113105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5121028 (2019).

Gottlieb, H. P. W. Harmonic balance approach to periodic solutions of non-linear jerk equations. J. Sound Vib. 271(3–5), 671–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-460X(03)00299-2 (2004).

Sprott, J. C. Some simple chaotic jerk functions. Am. J. Phys. 65, 537–543. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.18585 (1997).

Sprott, J. C. A new class of chaotic circuit. Phys. Lett. 266, 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(00)00026-8 (2000).

Petrzela, J. & Gotthans, T. New chaotic dynamical system with a conic-shaped equilibrium located on the plane structure. Appl. Sci. 7(10), 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7100976 (2017).

Jafari, S., Sprott, J. C., Pham, V.-T. & Golpayegani, S. M. R. H. A new cost function for parameter estimation of chaotic systems using return maps as fingerprints. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 24(10), 1450134. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021812741450134X (2014).

Petrzela, J. Strange attractors generated by multiple-valued static memory cell with polynomial approximation of resonant tunneling diodes. Entropy 20(9), 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/e20090697 (2018).

Chua, L. O., Komuro, M. & Matsumoto, T. The double-scroll family. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 33(11), 1072–1118. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCS.1986.1085869 (1986).

Matsumoto, T. A chaotic attractor from Chua´s circuit. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 31(12), 1055–1058. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCS.1084.1085459 (1984).

Parker, T. & Chua, L. O. The dual double-scroll equation. IEEE Trans. Circuit Syst. 34(9), 1059–1073. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCS.1987.1086267 (1987).

Bartissol, P. & Chua, L. O. The double hook. IEEE Trans. Circuit Syst. 35(12), 1512–1522. https://doi.org/10.1109/31.9914 (1988).

Nuñez-Perez, J.-C., Adeyemi, V.-A., Sandoval-Ibarra, Y., Perez-Pinal, F.-J. & Tlelo-Cuautle, E. Maximizing the chaotic behavior of fractional order Chen system by evolutionary algorithms. Mathematics 9(11), 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9111194 (2021).

Adeyemi, V.-A., Tlelo-Cuautle, E., Perez-Pinal, F.-J. & Nuñez-Perez, J.-C. Optimizing the maximum Lyapunov exponent of fractional order chaotic spherical system by evolutionary algorithms. Fractal Fract. 6(8), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract6080448 (2022).

Valencia-Ponce, M. A., Tlelo-Cuautle, E. & de la Fraga, L. G. Estimating the highest time-step in numerical methods to enhance the optimization of chaotic oscillators. Mathematics 9(16), 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9161938 (2021).

Kvarda, P. Identifying the deterministic chaos by using the Lorenz maps. Radioengineering 9(4), 32–33 (2000).

Kvarda, P. Identifying the deterministic chaos by using the Lyapunov exponents. Radioengineering 10(2), 38–40 (2001).

Qiu, H., Xu, X., Jiang, Z., Sun, K. & Cao, C. Dynamical behaviors, circuit design, and synchronization of a novel symmetric chaotic system with coexisting attractors. Sci. Rep. 13, 1893. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28509-z (2023).

Lu, R., Natiq, H., Ali, A. M. A., Abdolmohammadi, H. R. & Jafari, S. Synchronization of dissipative Nosé-Hoover systems: circuit implementation. Radioengineering 32(4), 511–522. https://doi.org/10.13164/re.2023.0511 (2023).

Delgado-Bonal, A. & Marshak, A. Approximate entropy and sample entropy: A comprehensive tutorial. Entropy 21(6), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21060541 (2019).

Xiaong, P.-Y. et al. Spectral entropy analysis and synchronization of a multi-stable fractional-order chaotic systems using a novel neural network-based chattering-free sliding mode technique. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 144, 110576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110576 (2021).

Munoz-Pacheco, J. M., Tlelo-Cuautle, E., Toxqui-Toxqui, I., Sanchez-Lopez, C. & Trejo-Guerra, R. Frequency limitations in generating multi-scroll chaotic attractors using CFOAs. Int. J. Electron. 101(11), 1559–1569. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207217.2014.880999 (2014).

Sprott, J. C. A proposed standard for the publication of new chaotic systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 21(9), 2391–2394. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021812741103009X (2011).

Petrzela, J. Fractional-order chaotic memory with wideband constant phase elements. Entropy 22(4), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22040422 (2020).

Biolek, Z., Biolek, D. & Biolkova, V. Differential equations of ideal memristors. Radioengineering 24(2), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.13164/re.2015.0369 (2015).

Muthuswamy, B. & Chua, L. O. Simplest chaotic circuit. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 20(5), 1567–1580. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218127410027076 (2010).

Funding

Brno University of Technology, Czechia, FEKT-S-23-8191.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

There is only one author of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrzela, J. Chaotic systems based on higher-order oscillatory equations. Sci Rep 14, 21075 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72034-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72034-6

This article is cited by

-

Chaos-enhanced manganese electrolysis: nodule suppression and improved efficiency using controllable chaotic electrical signals

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Study of Stability and Chaotic Behavior of a Parametrically Forced Oscillator Under Extreme Resonance

Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies (2025)