Abstract

The impact of preterm babies’ admission at the Neonatal Intensive Care (NICU) on the mental health of mothers is a global challenge. However, the prevalence and predictors of Common Mental Disorders (CMDs) among this population remain underexplored. This study assessed the predictors of CMDs among mothers of preterm infants in the NICUs in the Upper East Region of Ghana. A cross-sectional study was conducted, targeting mothers of preterm babies in two hospitals in the Upper East Region. The Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ-20) was used to collect data from 375 mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICUs. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 20. The study found a prevalence of 40.9% for CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the two NICUs. The predictors of CMDs were unemployment (aOR 2.925, 95% CI 1.465, 5.840), lower levels of education (aOR 5.582, 95% CI 1.316, 23.670), antenatal anxiety (aOR 3.606, 95% CI 1.870, 6.952), and assisted delivery (aOR 2.144, 95% CI 1.083, 4.246). Conversely, urban residence (aOR 0.390, 95% CI 0.200, 0.760), age range between 25 and 31 (aOR 0.238, 95% CI 0.060, 0.953), and having a supportive partner (aOR 0.095, 95% CI 0.015, 0.593) emerged as protective factors. This study emphasizes the imperative of addressing maternal mental health within the NICU setting for preterm births.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preterm birth, defined as the delivery of a baby before thirty-seven completed weeks of gestation, has been acknowledged as a global epidemic with significant implications for child health and development1. The worldwide incidence of preterm births is staggering, reaching 15 million cases, with a prevalence ranging from 5 to 18%2,3. This condition, characterized by gestational age, is further classified into extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks), very preterm (28 to < 32 weeks), and moderate to late preterm (32 to < 37 weeks)4.

Disparities in the gestational age of viability between Global-North and Global-South countries highlight the influence of healthcare infrastructure5. While the Global-North benefits from lower gestational age of viability due to well-established Neonatal Intensive Care services and expertise, the Global-South faces challenges with limited facilities and expertise, resulting in a higher gestational age of viability6,7.

Preterm babies are predisposed to various health complications, including respiratory, cardiovascular, metabolic, and gastrointestinal issues, contributing to a significant number of deaths among children under 5 years8,9. Beyond the direct health challenges faced by preterm babies, their families endure additional burdens. Studies, such as the one by Barsisa et al.10, reveal that families of preterm babies experience psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, and headaches, further exacerbated by the financial strain of treatment in intensive care setting11. Preterm babies require intensive care where they are properly managed by neonatal care physicians and nurses to ensure that they survive this period of their lives. In many Low- and Middle-income Countries (LMICs) like Ghana, preterm babies are not admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) alone since their mothers must be there with them expressing breast milk, provide support with kangaroo mother care (KMC) and perform other duties to ensure the survival of their babies. This period is a very stressful part of the postnatal period for all mothers with preterm neonates, but especially those who might have undergone caesarean section12. This then increases the risk of these mothers developing common mental disorders (CMDs)13.

Common mental disorders comprise of posttraumatic stress disorders, depression, generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders, social anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorders, and phobia14. Unfortunately, the female gender appears to be the worst hit bearing the brunt of mental disorders in LMICs15. The situation is however exacerbated during the postpartum period with evidence showing high prevalence of various mental health conditions including depression16. Daliri et al.17 reported the prevalence of depression among postpartum mothers as 50.4%.

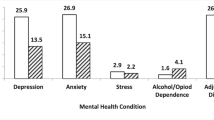

Mothers of preterm babies, in particular, face heightened levels of depression and anxiety compared to those with full-term babies18. This phenomenon is not limited to specific regions, as evidenced by an Indian study reporting significant prevalence rates of anxiety (66.2%) and depression (45.4%) among mothers with babies in the NICU19. Also, a Nigerian study reported the prevalence of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies to be 24%20. Ionio et al.21 in Italy and Roque et al.22 in the United States of America (USA) support these findings, emphasizing the elevated levels of tension-anxiety, depression, hostility, and anger experienced by mothers of preterm babies.

Crucially, the psychological challenges faced by mothers have a reciprocal impact on premature babies’ well-being and recovery. McGowan et al.23 found that mothers with psychological challenges were less prepared to take their preterm babies home, leading to prolonged hospital stays. This does not only affect the immediate recovery of the babies but also influences the long-term mental health and bonding between the mother and the child22,24.

Though these challenges exist, not all mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICU may develop CMDs. Studies have identified factors such as partner support, level of education, and employment status among others as associated factors in the development of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies20. A meta-analysis conducted in Iran identified factors such as maternal anxiety, mothers’ educational level and lack of prenatal care as predictors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies25. Studies from the US also confirmed maternal anxiety, chronic mental illness as predictors while social support and satisfaction with birth were identified as protective factors26. Furthermore, Mukabana et al.27 identified housing conditions and being on chronic medications as predictors of poor mental health outcomes among mothers of preterm babies admitted at the NICU. The above review points to the fact that various settings have some peculiar predictors of CMD and this calls for the identification of these factors in Ghana.

While institutional studies in Ghana report varying prevalence rates of preterm births, with figures ranging from 18.9% to 37.3%, the national perspective remains unclear28,29. Given that prematurity is a leading cause of infant mortality, addressing maternal mental health challenges becomes imperative for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3) target 3.4 which seeks to reduce by one-third preterm mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and to promote mental health and well-being. This study aimed to fill a crucial gap by focusing on the mental state of mothers with preterm infants in NICUs in the Upper East Region of Ghana, providing evidence to advocate for the presence of mental health professionals at NICUs to offer psychosocial support30. While several studies have explored the prevalence of CMDs among mothers with NICU babies, there is a notable dearth of research specifically addressing the unique challenges faced by mothers of preterm babies in the Upper East Region and probably Ghana as a whole, making this study a valuable contribution to the existing body of knowledge. Thus, this study assessed the prevalence and predictors of CMDs among mothers with preterm babies admitted to the NICUs at selected hospitals in the Upper East Region of Ghana. The study sought to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

What is the prevalence of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICUs?

-

2.

What are the predictors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICUs?

Methods

Study design & setting

This study employed a cross-sectional study design to collect data from mothers of preterm babies at the two NICUs.

The study was conducted in the Upper East region of Ghana. The region has a population of 1,301,22131. The region is made up of 15 districts with seven district hospitals, over 20 health centres and Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), and one regional hospital which is the only secondary-level hospital and the major referral hospital in the region. The regional hospital located in the Bolgatanga municipality provides services such as Obstetrics and gynecology, general surgery, psychiatry, internal medicine, and pediatrics with NICU services providing comprehensive care to all patients who attend the facility. The NICU has about 30 beds with 8 incubators and a space for mothers to undertake Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC). Being the only secondary facility in the region, it also serves parts of some neighboring countries like Burkina Faso and the Republic of Togo. Also, the Talensi District Hospital is one of the seven district hospitals in the region that provide NICU services. The NICU is made up of 15 beds with 4 incubators and is manned by a medical officer in conjunction with Pediatric nurses. They, however, refer more critical cases to the NICU of the regional hospital for specialist care. Due to logistic and human resource constraints, the NICUs do not provide palliative care. Therefore, extreme preterm babies who require palliative care are referred to tertiary hospitals for appropriate management. These two facilities were purposively selected because they manage the highest number of preterm babies in the region according to data from the District Health Information Management System (DHIMS-2).

Study population

Mothers of preterm babies admitted at the NICU of the Upper East Regional Hospital and the Talensi District Hospital.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

Mothers of preterm babies who were on admission at the Upper East Regional Hospital and the Talensi District Hospital and were 18 years and above.

Exclusion

-

(i)

Mothers who were mental health service users were excluded. This was excluded to ensure homogeneity in the sample and avoid confounders in the analysis.

-

(ii)

Mothers who did not consent to participate in the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size required for this study was calculated using the ‘Raosoft software’ (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html). Using a previously determined estimated 24% prevalence of CMDs among mothers with preterm babies admitted to the NICU, at a 95% confidence level, 5% (0.05) acceptable margin of error, and a 10% non-response rate, a sample size of 375 was obtained20. This sample was then distributed proportionally among the two hospitals involved in the study. Therefore, 230 respondents were selected from Upper East Regional Hospital and 145 were selected from the Talensi District Hospital.

Sampling method

The study employed a consecutive sampling technique to capture all women whose preterm babies were admitted to the NICU of the Upper East Regional Hospital and the Talensi District Hospital within the study period (1st November 2023 to 30th January 2024) until the sample size for each study site was achieved. This method was used to ensure that mothers of such admitted babies were captured while the babies were still on admission at the NICU. Also, none of the NICUs was large enough to have this number of mothers at a given time hence a probability sampling method wasn’t appropriate for this study.

Data collection tool and method

The study used an interviewer-administered questionnaire which had two sections. The first section was made up of the sociodemographic characteristics of the mother and the preterm baby. This section contained variables such as age, employment status, educational level, marital status, partner support, living with partner, maternal medical condition, parity, type of pregnancy, planned pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, mode of delivery, and duration of admission as identified from previous studies26,32. The second section contained 20 questions of the Self-report questionnaire (SRQ-20). This is a standardized tool developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to assess CMDs33. It is made up of 20 questions with binary responses (Yes/No) which assesses CMDs (Depression, anxiety-related disorders, and somatoform disorders). The SRQ has been described as the appropriate tool for assessing CMDs34 in LMICs. The SRQ was found to have a Cronbach Alpha of 0.85 among women in Rwanda35, a LMIC like Ghana. In Ghana, a cutoff point of 5 for the SRQ-20 has been found to be adequate in identifying mental distress among women36 and this was used as the cutoff in this study. In this study, SRQ scores < 5 was considered unlikely to have CMDs (Depression, anxiety-related disorders, and somatoform disorders). The tool was translated into Grune which is the popular language of the people in the region and translated back to English by a professional linguist. Respondents who could neither read nor write were interviewed using the Grune version. A pretest of the tool was conducted among 10 mothers and all the necessary adjustments to the tool were made.

All interviews were conducted in private rooms in the NICUs of both hospitals. The study was explained to the participants and those who consented were recruited into the study. Data collected from this study were stored on a password-protected computer accessible only to the researchers.

Outcome and explanatory variables

The outcome variable was mental distress which was grouped into “CMD” not mentally distressed” and “No CMD” using the SRQ-20. Mothers whose SRQ-20 score was < 5 were considered mentally distressed. The explanatory variables were demographic characteristics (age, employment status, Level of education, marital status, partner support, living with a partner, type of residence), obstetric characteristics (parity, type of pregnancy, planned pregnancy, maternal medical condition, gestational age,) neonatal characteristics (birth weight, mode of delivery length of admission (from the day of admission to the day of the interview)), and maternal mental health characteristics (antenatal anxiety, substance use in pregnancy, passive smoking during pregnancy).

Data analysis

Data collected were cleaned and imported onto SPSS version 20 and analysed. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of respondents and estimated the prevalence of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies at the NICUs. Chi square test was used to establish the association between the outcome variable (CMDs) and the independent variables. Multivariate logistic (binary) regression analysis was used to establish the predictors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies. The results of the multicollinearity test indicated that all explanatory variables had a variance inflation factor (VIF) below 10, thus none required exclusion according to Chatterjee et al.37, as shown in Appendix S1. The outcomes of the multivariate logistic regression analysis were expressed as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) along with their corresponding confidence intervals (CIs). A P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

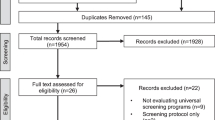

A total of 375 mothers of preterm babies admitted at the NICU were recruited with a 97.6% response rate. Data from 9 participants were incomplete hence data from 366 participants were included in the analysis.

The mean age of participants was 34.41 ± SD 6.69. Out of this number, most participants (38%) were in the age range of 25–31 years. More than half of the participants (63.7%) were employed and 12.3% of participants had no formal education. Also, an overwhelming majority (87.5%) were married with 53.0% being multiparous and most of the pregnancies being singleton (83.9%). Concerning gestational age at delivery, a little over half (54.1%) of the pregnancies terminated between 28 and 32 weeks resulting in 61.2% of babies with low birth weight. Substance use in pregnancy was positive among 6.8% of the mothers and the majority (65.8%) lived in urban communities. Further details have been presented in Table. 1.

Prevalence of common mental disorders among mothers of preterm babies

The prevalence of common mental disorders among participants was 40.4% as shown in Fig. 1.

Factors associated with CMDs among mothers of preterm babies

In terms of age, there was generally a lower number of participants with CMDs in all age ranges except those between the ages of 18–24. The same was recorded for educational status as fewer mothers rated positive for CMDs compared to those who scored negative except for people with tertiary education. Among the employment group, more unemployed people rated positive for CMDs as compared to those employed. Most married people rated negative for CMDs compared to single and divorced/widowed. Parity, type of pregnancy, partner support, maternal medical condition, substance abuse, and type of residence showed a lower number of positives for CMDs compared to those who rated negative. However, there were variations in responses in terms of antenatal anxiety, length of admission, mode of delivery, birth weight, gestational age, living with partner, and partner support. Further details are presented in Table 2.

In the multivariate analysis, unemployed mothers had higher odds of developing CMDs compared with those employed (aOR 2.925, 95% CI 1.465, 5.840). Also, mothers with primary education (aOR 5.582, 95% CI 1.316, 23.670), Senior high school (aOR 4.61, 95% CI 1.517, 14.318), tertiary education (aOR 3.689, 1.260, 10.804), living with a partner (aOR 13.073, 95% CI 2.114, 80.856), assisted delivery (aOR 2.144, 95% CI 1.083, 4.246), antenatal anxiety (aOR 3.606, 95% CI 1.870, 6.952) had higher odds for CMD. Despite these, people living in Urban areas (aOR 0.390, 95% CI 0.200, 0.760), partner support (aOR 0.095, 95% CI 0.060, 0.953), age range between 25 and 31 (aOR 0.238, 95% CI 0.015, 0.593) were less likely to develop CMDs (Table 3).

Discussion

This study was a multicenter study that assessed the prevalence and predictors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICU of selected hospitals in the Upper East region of Ghana.

The prevalence of CMDs among the participants in the selected facilities was 40.4% implying that 2 out of 5 mothers in this study had CMDs. This underscores the significant psychological burden faced by mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICU. This aligns with global research indicating that mothers of preterm babies are at an increased risk of mental health issues38. Studies from various countries, such as the United States (USA)39, the United Kingdom (UK)40, and Australia13, have consistently reported elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and stress among mothers of preterm babies, emphasizing the universality of this concern. This finding is consistent with findings by Rogers et al.41 who reported a prevalence of CMDs of 43% among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICU in the US. This prevalence is however lower than the findings by Mukabana et al.27 who reported a prevalence of 83.5% of negative mental health outcomes among mothers of preterm babies admitted at the NICU in Kenya. This difference may have emanated from the low sample size (182) used in their study. The finding is higher than the prevalence rate (24%) reported in a similar study in Nigeria by Alao et al.20. This may have been influenced by the cut-off point used. In this study, a cut-off point of 5 was used while in the Nigerian study, a cut-off point of 8 was used.

Findings from this study showed that unemployment was a predictor of CMDs, and this is consistent with existing literature. Unemployment has been identified as a risk factor for poor mental health outcomes, and this finding aligns with studies worldwide42,43. Our findings highlight a vulnerable group of mothers who may have fewer resources (both through internal coping mechanisms as well as external support) to deal with the challenges of having a preterm baby.

The educational status of mothers also emerged as a significant risk factor, with those having only primary education exhibiting higher odds for CMDs. This echoes findings from global studies emphasizing the role of education in maternal mental health. Higher levels of education are often associated with better mental health outcomes, including lower rates of depression and anxiety44. The finding is consistent with previous studies in Nigeria20. However, findings from this study showed that apart from Junior high school, all other levels of education were significantly associated with CMDs. This finding indicates that some intrinsic factors may be accountable for the increased risk of mothers in this study despite their higher levels of education. A possible explanation to this might be the fact that people with higher educational levels may understand the implications of prematurity and its associated sequelae better hence very much likely to be mentally distressed compared to mothers who may not have better appreciation of the condition and its sequelae.

The findings related to antenatal anxiety and assisted delivery as predictors of CMDs align with existing literature on the association between pregnancy-related factors and maternal mental health45. These results emphasize the importance of addressing maternal mental health throughout the entire perinatal period, from antenatal care to delivery and beyond. These findings are consistent with Dolatian et al.25 in a meta-analysis in Iran who reported that antenatal anxiety and type of delivery increased the risk of CMDs among Mothers of preterm babies.

In this study, urban residence was found to be a protective factor against CMDs among mothers of preterm babies. This finding however contrasts with some global trends46. Urban areas may offer better access to healthcare services and support networks, buffering against the stressors associated with preterm birth 47.

Also, partner support emerged as a protective factor for mothers of preterm babies against CMDs. This aligns with extensive research demonstrating the positive impact of social support on maternal mental health48,49,50. This result is consistent with previous research showing that having a spouse in the home improves a mother’s mental health and level of life satisfaction51. Also, the age range 24–31 was found to be protective. This is supported by previous studies that reported higher odds of CMD among older mothers with preterm babies52. It is however contradicted by Alao et al.20.

Conclusion

This study sought to examine the prevalence and risk factors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted to the NICUs in the Upper region of Ghana. The study provides valuable insights into the mental health challenges faced by mothers of preterm infants in the Upper East Region of Ghana. The identified risk factors and protective factors contribute to the evidence base for designing targeted interventions aimed at improving maternal mental health in similar settings. Policymakers and healthcare professionals can utilize these findings to inform the development of strategies that address the unique socio-economic and cultural context of the region, ultimately enhancing the well-being of mothers and their babies in the NICU.

Implications for practice

Considering the prevalence of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies admitted at the NICU, healthcare providers in NICU settings should prioritize screening for maternal mental health conditions, particularly among vulnerable populations such as unemployed or less-educated mothers. Interventions aimed at promoting social support, addressing financial stressors, and providing education and resources for coping with preterm birth should be integrated into NICU care protocols. Additionally, policymakers should prioritize investments in mental health services and social support programs targeted at high-risk populations to mitigate the burden of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies at the NICU.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is probably the first study assessing the prevalence and risk factors of CMDs among mothers of preterm babies on admission at the NICU in the Ghanaian setting. This study used a standardized tool, the SRQ-20 to assess CMDs among mothers of preterm babies. This study captures a diverse sample, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the prevalence and risk factors for common mental disorders (CMDs).

The findings, however, must be interpreted with some caveats. The use of self-reported data, especially for mental health assessment, may introduce response bias. Participants might underreport or overreport symptoms due to social desirability or recall bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of CMDs prevalence estimates. However, this was minimized by ensuring that interviewers were properly trained to avoid judgmental questions and postures. Also, the study only considered information of one twin if both twins were on admission. Since twins may have different characteristics, settling on the information of one twin might affect the outcomes of the study. This was however minimized since most mothers of twins only had one twin on admission.

The study also employed non-probability sampling (consecutive sampling). While this approach may be practical, it could introduce selection bias. This was however minimized by ensuring that the researchers abided by the exact inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its Supplementary information files].

References

Shapiro-Mendoza, C. K. et al. CDC grand rounds: Public health strategies to prevent preterm birth. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65(32), 826–830 (2016).

Blencowe, H. et al. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod. Health 10(Suppl 1), S2 (2013).

Ohuma, E. O. et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: A systematic analysis. The Lancet 402(10409), 1261–1271 (2023).

Barfield, W. D. Public health implications of very preterm birth. Clin. Perinatal. 45(3), 565–577 (2018).

Kornhauser Cerar, L. & Lucovnik, M. Ethical dilemmas in neonatal care at the limit of viability. Children 10(5), 784 (2023).

Breborowicz, G. H. Limits of fetal viability and its enhancement. Early Pregnancy (Cherry Hill) 5(1), 49–50 (2001).

Aniedu, P. N. et al. Successfully managed extremely low birth weight baby in a resource limited setting. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 17(1), 783–789 (2023).

Muhe, L. M. et al. Major causes of death in preterm infants in selected hospitals in Ethiopia (SIP): A prospective, cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Glob. Health 7(8), e1130–e1138 (2019).

Behrman, R. E. & Butler, A. S. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention (National Academies Press, Washington, 2007).

Barsisa, B., Derajew, H., Haile, K., Mesafint, G. & Shumet, S. Prevalence of common mental disorder and associated factors among mothers of under five year children at Arbaminch Town, South Ethiopia, 2019. PLOS ONE 16(9), e0257973 (2021).

Lakshmanan, A. et al. The impact of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: A cross-sectional study in the 2 years after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15(1), 38 (2017).

Carter, J. D., Mulder, R. T. & Darlow, B. A. Parental stress in the NICU: The influence of personality, psychological, pregnancy and family factors. Personal. Mental Health 1(1), 40–50 (2007).

Vigod, S. N., Villegas, L., Dennis, C. L. & Ross, L. E. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: A systematic review. BJOG Int. J. Obst. Gynaecol. 117(5), 540–550 (2010).

Prescott, S.L., Greeson, J.M., El-Sherbini, M.S. Health PHCCbtNIf: No health without mental health: Taking action to heal a world in distress—with people, places, and planet ‘in mind’. In: MDPI (2022).

Abdullahi, A. T., Farouk, Z. L. & Imam, A. Common mental disorders in mothers of children attending out-patient malnutrition clinics in rural North-western Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1–9 (2021).

Rai, S., Pathak, A. & Sharma, I. Postpartum psychiatric disorders: Early diagnosis and management. Indian J. Psychiatry 57(Suppl 2), S216-221 (2015).

Daliri, D. B., Afaya, A., Afaya, R. A. & Abagye, N. Postpartum depression: The prevalence and associated factors among women attending postnatal clinics in the Bawku municipality, Upper East Region of Ghana. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. Rep. 2(3), e143 (2023).

Trumello, C. et al. Mothers’ depression, anxiety, and mental representations after preterm birth: A study during the infant’s hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front. Public Health 6, 359 (2018).

Deshwali, A. et al. Prevalence of mental health problems in mothers of preterm infants admitted to NICU: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 160(3), 1012–1019 (2023).

Alao, M. A. et al. Factors associated with common mental disorders among breastfeeding mothers in tertiary hospital nurseries in Nigeria. PLOS ONE 18(3), e0281704 (2023).

Ionio, C. et al. Mothers and fathers in NICU: The impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur. J. Psychol. 12(4), 604 (2016).

Roque, A. T. F., Lasiuk, G. C., Radünz, V. & Hegadoren, K. Scoping review of the mental health of parents of infants in the NICU. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 46(4), 576–587 (2017).

McGowan, E. C. et al. Maternal mental health and neonatal intensive care unit discharge readiness in mothers of preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 184, 68–74 (2017).

Friedman, S. H., Yang, S. N., Parsons, S. & Amin, J. Maternal mental health in the neonatal intensive care unit. NeoReviews 12(2), e85–e93 (2011).

Dolatian, M. et al. Preterm delivery and psycho-social determinants of health based on world health organization model in Iran: A narrative review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 5(1), 52–64 (2012).

Gong, J. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal mental health problems in mothers of infants admitted to neonatal care: Analysis of two population-based surveys in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23(1), 370 (2023).

Mukabana, B., Makworo, D. & Mwenda, C. Mental health outcomes and associated predictors among mothers of preterm infants: A cross-sectional study. East Afr. Med. J. 100(4), 5776–5786 (2023).

Adu-Bonsaffoh, K., Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Oppong, S. A. & Seffah, J. D. Determinants and outcomes of preterm births at a tertiary hospital in Ghana. Placenta 79, 62–67 (2019).

Anto, E. O. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of preterm birth among pregnant women admitted at the labor ward of the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital, Ghana. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 3, 801092 (2022).

Hynan, M. et al. Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. J. Perinatol. 35(1), S14–S18 (2015).

Service, G.S. 2021 Population and Housing Census General Report. Ghana Statistical Service, Accra, Ghana; 2021 (2021).

Deshwali, A. et al. Prevalence of mental health problems in mothers of preterm infants admitted to NICU: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 160(3), 1012–1019 (2023).

Beusenberg, M., Orley, J.H., Organization WH. A user’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ/compiled by M. Beusenberg and J. Orley). (1994).

Ali, G. C., Ryan, G. & De Silva, M. J. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One 11(6), e0156939 (2016).

Scholte, W. F., Verduin, F., van Lammeren, A., Rutayisire, T. & Kamperman, A. M. Psychometric properties and longitudinal validation of the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20) in a Rwandan community setting: a validation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11(1), 116 (2011).

Amoako, Y. A. et al. Mental health and quality of life burden in Buruli ulcer disease patients in Ghana. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10(1), 109 (2021).

Chatterjee, S. & Hadi, A. S. Regression Analysis by Example (Wiley, New Jersey, 2015).

Adu-Bonsaffoh, K. et al. Women’s lived experiences of preterm birth and neonatal care for premature infants at a tertiary hospital in Ghana: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2(12), e0001303 (2022).

Field, T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 33(1), 1–6 (2010).

Treyvaud, K. et al. Parenting behavior at 2 years predicts school-age performance at 7 years in very preterm children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57(7), 814–821 (2016).

Rogers, C. E., Kidokoro, H., Wallendorf, M. & Inder, T. E. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J. Perinatol. 33(3), 171–176 (2013).

Paul, K. I. & Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 74(3), 264–282 (2009).

Olesen, S. C., Butterworth, P., Leach, L. S., Kelaher, M. & Pirkis, J. Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health: Findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry 13(1), 1–9 (2013).

Ross, C. E. & Mirowsky, J. The interaction of personal and parental education on health. Soc. Sci. Med. 72(4), 591–599 (2011).

Canário, C. & Figueiredo, B. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in women and men from early pregnancy to 30 months postpartum. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 35(5), 431–449 (2017).

Blazer, D. et al. Psychiatric disorders: A rural/urban comparison. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 42(7), 651–656 (1985).

Evans, G. W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health 80, 536–555 (2003).

Schetter, C. D. & Tanner, L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25(2), 141 (2012).

Antoniou, E., Stamoulou, P., Tzanoulinou, M. D. & Orovou, E. Perinatal mental health; the role and the effect of the partner: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 9(11), 1572 (2021).

Atif, M., Farooq, M., Shafiq, M., Ayub, G. & Ilyas, M. The impact of partner’s behaviour on pregnancy related outcomes and safe child-birth in Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23(1), 516 (2023).

Levis, B. et al. Using marital status and continuous marital satisfaction ratings to predict depressive symptoms in married and unmarried women with systemic sclerosis: A Canadian scleroderma research group study. Arthritis Care Res. 68(8), 1143–1149 (2016).

Nguyen, P. H. et al. Maternal mental health is associated with child undernutrition and illness in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr. 17(6), 1318–1327 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all mothers of preterm babies in the NICU of both hospitals who agreed to participate in this study. We are also grateful to the management of the hospitals for their permission to conduct the study in their facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.B.D. conceived the study with A.A. M.J., B.G., G.B., M.A., S.A.O., T.T.L., R.D., A.S.S., F.K.W., A.A.A., M.A.A., N.A., B.A., and M.S., collected the data and contributed to reviewing the manuscript. D.B.D. analyzed the data in consultation with A.A. D.B.D. and T.T.L. wrote the manuscript. A.A. supervised the study. All the authors read, reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology with approval number CHRPE/ AP/997/23. Also, written institutional permission was obtained from the Upper East Regional Hospital and the Talensi District Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian of respondents who were minors. The respondents were informed about their rights to voluntarily participate and withdraw without penalties. All the respondents were required to give a written consent before being included in the study. The privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity of respondents were protected throughout the study. The student adhered to all the relevant ethical principles and guidelines in conducting human research..

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daliri, D.B., Jabaarb, M., Gibil, B.V. et al. Prevalence and predictors of common mental disorders among mothers of preterm babies at neonatal intensive care units in Ghana. Sci Rep 14, 22746 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72164-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72164-x