Abstract

Replicating the complex 3D microvascular architectures found in biological systems is a critical challenge in tissue engineering and other fields requiring efficient mass transport. Conventional microfabrication techniques often face limitations in creating extensive hierarchical networks, especially within bulk materials. Here, we report a versatile bioinspired approach to generate optimized 3D microvascular networks within transparent glass matrix by transcribing the natural growth patterns of plants and fungi. Plant seeds or fungal spores are first cultivated on nanoparticle-based culture media. Subsequent heat treatment removes the biological species while sintering the surrounding compound into a solidified chip with replica root/hyphal architectures as open microchannels. A diverse range of architectures, including the hierarchical branching of plant roots and the intricate networks formed by fungal hyphae, can be faithfully replicated. The resultant glass microvascular networks exhibit high chemical and thermal stability, enabling applications under harsh conditions. Fluid flow experiments validate the functionalities of the fabricated channels. By co-cultivating plants and fungi, hierarchical multi-scale architectures mimicking natural vascular systems are achieved. This bioinspired manufacturing technique leverages autonomous biological growth for architectural optimization, offering a complementary approach to existing microfabrication methods. The transparent nature of the glass chips allows for direct optical inspection, potentially facilitating integration with imaging components. This versatile platform holds promise for various engineering applications, such as microreactors, heat exchangers, and advanced filtration systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In biological organisms, efficient transport of oxygen, nutrients, and waste is facilitated by complex 3D vascular networks that have evolved through natural optimization processes1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These biologically optimized microvascular architectures play a crucial role in maintaining tissue functions and enabling life. In the field of tissue engineering, one of the major challenges lies in artificially replicating such vascular structures within engineered scaffolds to create functional tissue constructs with biomimetic properties.

Conventional microfabrication techniques have provided various approaches to realize extensive 3D networks within bulk materials. Methods such as stacking 2D planar microchannels8,9,10,11,12,13 or stereolithography14 have been developed to create complex 3D structures. Other approaches, such as electrospinning15 and melt spinning16,17, have also contributed to the formation of microstructures. Recently, a novel approach utilizing high-energy electrical discharges has emerged, enabling the instantaneous formation of tree-like microvascular networks within scaffold materials18.

In the field of glass microfabrication, significant progress has been made in developing techniques to create transparent microstructures. Similar to ceramics, glass powder metallurgy processes are being actively developed19,20,21,22. The use of fine powders enables the fabrication of intricate structures, with extensive efforts focused on enhancing transparency while maintaining the amorphous state during sintering23,24,25,26. In this context, Kotz and colleagues have reported innovative microfabrication techniques using nanosilica particles27,28,29. Their method combines the dispersion of fine silica particles in plastic or UV-curable resins with advanced fabrication technologies such as two-photon polymerization, achieving high-resolution 3D structures. The formed microstructures were transformed into transparent dense glass products by the subsequent heating process. This technology has made significant progress in the fabrication of precise microstructures.

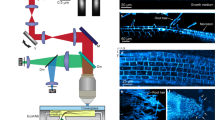

In this study, we report a versatile bioinspired microfabrication technique to create optimized 3D microvascular networks within a transparent glass matrix. By exploiting the natural growth patterns of plants and fungi within nanopowder compounds, their intricate architectures are transcribed into microchannels during a sintering process (Fig. 1). A plant seed or fungal spores are first cultivated on a silica nanoparticle-based culture medium. Upon subsequent sintering, the biological species are removed, leaving behind a replica of their root/hyphal network as hollow channels within a solidified transparent glass chip.

Fabrication of 3D microvascular networks by plant cultivation method. (a) Process flow of the proposed technique. A plant seed is cultivated on a culture medium containing silica nanoparticles. After cultivation, the sample is heat-sintered to remove the plant while transcribing its root structure into hollow microchannels within a transparent glass chip. (b) Sample view during plant cultivation stage. (c) Sintered glass chip containing replicated root channels after heat treatment. (d) Optical micrograph of the transparent glass chip, showing the root-shaped microchannels resembling a live plant.

While Kotz et al. have made significant advances in fabricating microstructures using finely dispersed silica particles in UV-curable resins, our approach differs fundamentally in its biocompatibility and simplicity. We focus on the inherent biocompatibility of silica, prevalent in nature, and have developed a process using entirely non-toxic binders. Unlike conventional methods that often involve organic solvents incompatible with living organisms, or water-soluble binders like PVA that inhibit root growth (see Fig. S2), our method allows for the direct cultivation of living organisms within the fabrication medium. This enables us to harness the natural growth patterns of biological structures directly in the manufacturing process.

Our previous work30 also focused on the fabrication of transparent structures, this study aims to evaluate the functionality of these biologically inspired channels for fluid transport, marking a significant step towards practical applications in microfluidics and other engineering fields.

This bioinspired approach offers several key advantages. First, it leverages the autonomous architectural optimization capabilities of biological systems to generate complex 3D geometries without relying on multi-step lithographic or additive manufacturing processes. Second, the use of glass materials imparts excellent chemical stability, hardness, and thermal resistance, enabling applications under harsh conditions or elevated temperatures. Moreover, the transparency of the final product allows direct optical inspection and integration with imaging components.

Compared to plant roots, fungal hyphae represent an even finer network architecture, allowing the fabrication of hierarchical multi-scale channels by co-cultivating plants and fungi. Such architectures, mimicking the vascular systems in natural tissues, are highly desirable for tissue engineering and other applications requiring efficient mass transport.

This paper presents the development of the proposed bioinspired microfabrication method and characterization of the resultant 3D microvascular networks within glass chips. Subsequent sections detail the fabrication process, structural analysis, fluid flow characterization, and discuss the advantages, potential applications, and future prospects of this versatile technique. This technique has potential applications in various fields. For example, the hierarchical structures inspired by biological circulatory systems could be effectively applied in heat exchangers and catalytic reactors. Moreover, by controlling the porosity of the matrix during sintering, these structures could be adapted for pressure-distributed filtering applications.

Results

Glass channel structures

Figure 2 shows photographs of the sintered glass chip samples. Transparent glass chips contain channel structures closely replicating the morphology of the grown plant roots and fungal hyphae. Figure 2a is a sample using radish, Fig. 2b white clover, and Fig. 2c rye grass. Root architectures are transcribed regardless of plant species. Main roots have thicknesses of 200–300 μm, while root hair channels are commonly 7–9 μm in diameter. Figure 2d shows channels formed by the fungus Aspergillus oryzae, exhibiting a repeatedly branching and reconnecting hyphal network structure within the glass, distinct from plant roots. This demonstrates the ability to replicate diverse topologies. Cross-sections of the root hair channels, prepared by cutting and polishing, are observed in Fig. 2e for white clover, revealing nearly circular shapes. Figure 2f shows the cross-section of an Aspergillus channel with a width of 1–2 μm.

Quantitative analysis of channel dimensions

To quantitatively check the fidelity of our replication process and understand the dimensional changes occurring during sintering, we conducted extensive measurements of both the biological root hairs and the resulting glass microchannels. To ensure consistent conditions, the biological root hairs were cultivated in the same nano-silica dispersed medium used for the fabrication process. After cultivation, the roots were carefully washed in water to remove silica nanoparticles before measurement. Images of these prepared biological samples are shown in Fig. S4. The diameters of 40 biological root hairs were measured following this preparation process. After the sintering process, we measured the diameters of 64 corresponding microchannels within the glass chip using cross-sectional imaging.

Statistical analysis of these measurements revealed that the mean diameter of the glass microchannels was 81.1% of the original root hair diameter. Interestingly, this retention ratio closely matched the macroscopic size reduction of the entire glass chip after sintering, which was also measured to be approximately from 80 to 81%.

Figure 3 shows the histogram of diameters for both the prepared root hairs and the resulting glass microchannels. The consistency in shrinkage across different scales—from individual microchannels to the entire chip—suggests that the biological structures undergo uniform, isotropic contraction during the sintering process.

Histograms of root hair thickness of live plant roots cultured in silica slurry and root hair shape glass channel thickness after sintering. Forty points were evaluated for living organisms and 64 points for glass channels. The mean thickness of the living root hairs was 10.1 μm and the mean thickness of the glass channels was 8.2 μm.

The observed 81% retention of the original dimensions indicates that our process preserves the essential architectural features of the biological template while allowing for some densification of the glass matrix. Moreover, the consistency of shrinkage between the microscopic channels and the macroscopic chip dimensions suggests that the internal structures maintain their relative spatial relationships during sintering. This preservation of topology is essential for accurately replicating the complex, hierarchical architectures found in biological vascular networks.

Fluid flow experiments

While microscopy confirms the presence of root hair and hyphal channel structures, fluid flow experiments were conducted to validate their functionality (Movies S1 and S2), with snapshots shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Figure 4 shows the overview of the glass chip containing the replicated main root channel. A dye solution was introduced at the right end of the channel using a syringe. Snapshots of the dye progression through the channel at different time points are shown. The solution successfully traversed the entire length of the main root channel. While numerous root hair-shaped channels exist, not all of them are filled with fluid in this example due to trapped air in these closed channels.

Figure 5a–c depict dye solution flow within root hair channels, where one side was exposed by polishing to allow capillary injection via a glass micropipette. The solution automatically flows toward the main root driven by capillary action. Figure 3d–e demonstrate flow within the fungal hyphal channels.

Plant root-fungal hypha multilevel structure

Figure 6 shows a sample replicating the symbiotic environment of rye grass and mycorrhizal fungi. Figure6a depicts the cultivation stage with two rye grass plants grown for two weeks. The sintered glass sample's appearance is shown in Fig. 6b. Optical micrographs in Fig. 6c reveal long root extensions within the compound, with numerous root hairs around 10 μm in width branching from the main roots of approximately 150 μm diameter. Simultaneously, channels formed by 2–3 μm wide mycorrhizal fungal hyphae are observed enveloping the roots.

Discussion

Before discussing the main findings, it is important to explain how this work builds on our previous studies. Our earlier work involved replicating biological structures in opaque ceramic materials31, which made it difficult to see the internal structures. We then worked on reducing bubble formation during fabrication of transparent glass structures30. Importantly, we have shown that these channels can actually transport fluids, not just mimic the shape of biological structures. The key advancement in this study is not an improvement in transparency over our previous work, but rather the functional evaluation of these structures as microfluidic channels, including quantitative analysis of their dimensions and demonstration of fluid flow. By recreating both plant roots and symbiotic fungi, we have captured more of the complexity found in natural biological systems. These improvements create a more useful fabrication technique that could be applied in various fields of engineering.

Theoretical studies have been conducted to maximize the transport efficiency of fluids within arbitrary transport networks, considering factors such as fluid viscosity, total circuit length, surface area, and volume. It has been shown that the branching structures of the aorta extending from the heart in animals and the channel structures in plants have optimized configurations that minimize energy consumption32,33,34. The vascular-like network structures obtained in this study, being transcribed from biological structures, inherently possess these optimized channel geometries.

The use of glass material offers excellent chemical and thermal stability, enabling applications in harsh environments or high temperatures. The transparency also allows optical access, facilitating integration with imaging components if required. These properties, combined with the biologically-optimized structures, open up possibilities for applications in fields such as microreactors, heat exchangers, and advanced battery designs, where complex 3D architectures can significantly enhance performance.

The principles and methods developed in this study have potential in various engineering fields. As demonstrated by Bejan and Lorente35, tree-shaped flow structures derived from constructal theory have wide-ranging applications in engineering design. Our work extends this approach, offering novel methods for creating optimized flow structures. Although we do not directly investigate heat exchange applications, it's important to note that microfluidic devices for heat exchange are an active area of research and development. The plant root and fungal hyphal networks replicated in our study exhibit multi-scale structures that coincide with the scale of mammalian vascular systems, which could be beneficial for heat exchanger designs.

Following the multi-objective optimization approach of Nava-Arriaga et al.36, we can envision several potential applications for our technology, including microreactors for enhanced chemical processes, advanced cooling systems for electronic devices, and multi-level filtration systems for industrial applications. The vast diversity of plant and fungal species offers the potential to select structures that align with specific device design parameters, providing a wide range of naturally optimized geometries for various engineering applications. Future work will focus on adapting our fabrication process to materials more suitable for these specific applications, and on quantifying the performance improvements offered by our bioinspired designs in each of these contexts.

Also, the quantitative analysis of channel dimensions provides further insight into the fidelity and predictability of our fabrication process. The observed retention ratio of approximately 81% in our glass chip samples aligns well with theoretical predictions. These samples were prepared using a slurry medium containing 50 vol% silica. Assuming complete densification during sintering, the theoretical linear shrinkage can be calculated as 1–0.51/3, which is approximately 20%. The close agreement between this theoretical value and our observed retention ratio of about 81%, or shrinkage ratio of about 19%, supports the conclusion that our sintered glass chips are nearly fully dense.

Regarding resolution, the sintering process led to shrinkage of features compared to their initial biological sizes. For instance, the 7–9 μm root hair channels originated from ≈10 μm root hairs, and the sub-micron hyphal channels replicated ≈3 μm fungal hyphae. This scaling is influenced by the nanoparticle size (0.5 μm silica used here) and the extent of densification during sintering. The use of finer nanoparticles could potentially improve resolution further, although very fine features below 1 μm were successfully transcribed even with the current materials.

This technique also offers a novel approach to visualize and study the intricate dynamics within the rhizosphere, providing insights into plant-fungi interactions, root architecture development, and other underground biological processes typically challenging to observe directly. The fixation and 3D preservation of such systems could find applications in educational tools, theoretical modeling, and fundamental biological research.

The fluid flow results (Fig. 3) validated the continuity and interconnectivity of the fabricated channels, enabling their implementation in microfluidic devices, micro-reactors, membrane technology, and other applications requiring controlled fluid transport. The hierarchical architecture observed in the plant-fungal symbiotic system (Fig. 4) is particularly promising for tissue engineering, where replicating the multi-scale vascular networks present in natural tissues is crucial for nutrient/waste exchange.

Comparing the scale and structure of the fabricated channel networks with their biological counterparts, it is evident that they cover the range of the mammalian vascular network. The fine capillaries constituting the capillary network have diameters of 6–7 μm37, which is equivalent to the scale of the channels generated by root hairs in this study. Furthermore, while the structure obtained from a single plant individual comprises a multi-level branching architecture emanating from a main vessel, the fungal mycelia can connect multiple plant individuals, enabling the replication of a topology that mimics the multi-level and fine capillary network bridging arteries and veins.

This dimensional similarity between our fabricated structures and biological vasculature is a significant achievement. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of our current approach. While our glass-based structures accurately replicate the dimensions of biological vasculature, including capillaries, direct endothelial cell culture on these glass substrates would not be feasible due to the material properties and fabrication process.

Additional challenges include the control of biological growth patterns. Although we can influence plant structure to some extent using gravitropism and phototropism, this control remains probabilistic. Establishing more precise methods to guide biological growth for predictable structure formation is an area for future research. From an engineering perspective, developing effective post-processing techniques, particularly for connecting inlet and outlet ports to the internal channel structure, is crucial for practical applications of these glass chips.

These limitations present opportunities for future work. Exploring more biocompatible materials that could allow for direct cell integration while maintaining the complex architectures achieved through our bioinspired approach is a promising direction. Additionally, investigating techniques to transfer these intricate channel structures to more cell-friendly substrates could bridge the gap between our current structural achievements and functional biological models.

Despite these challenges, our approach demonstrates the potential of leveraging biological growth patterns to create optimized transport networks. The insights gained from this work could inform the design of future vascular models and find applications in fields ranging from microfluidics to efficient heat exchanger design, even as we continue to address the current limitations.

In summary, the proposed bioinspired approach combines the autonomous architectural optimization by biological systems with the desirable material properties of ceramics/glasses. This synergy enables the fabrication of optimized 3D microvascular networks with potential impacts across diverse fields. The hierarchical structures, directly mimicking biological circulatory systems, offer promising applications in fields such as heat exchange and catalytic reactions. The hierarchical nature of these structures could enhance efficiency in these processes by optimizing flow distribution and surface area. Furthermore, by adjusting the sintering process to maintain a degree of porosity in the matrix, rather than full densification, we can create structures capable of distributed pressure filtering. These potential applications demonstrate how the complex, biologically-inspired structures we've created can be adapted to solve engineering challenges, bridging the gap between natural design principles and technological innovation. Future work will focus on optimizing these structures for specific engineering applications and exploring new fields where these bioinspired designs could offer unique advantages.

Methods

Materials

For the plant culture medium, a compound material consisting of nanosilica particles dispersed in water with a binder was used. The nanosilica powder (SC2500-SQ, Admatechs) had an average particle size of 0.5 μm and was selected for its good dispersibility in water. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a commonly used water-soluble binder, was found to inhibit plant growth in our preliminary experiments (Fig. S2). Therefore, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) was selected as an alternative binder that does not hinder the biological species during cultivation. The biological species used were radish (Raphanus sativus), white clover (Trifolium repens), and rye grass (Secale cereale) seeds for plants, and the fungus Aspergillus oryzae for fungi. For mycorrhizal fungi, a gel-based concentrated mycorrhizal inoculum (Mycogel, Hyponex) containing spores of Rhizophagus irregularis was used.

Cultivation

The compound material was prepared by mixing the nanosilica powder with a 0.5 mass% HPMC aqueous solution in volume ratios of 50:50 or 30:70. To achieve good dispersion, a planetary vacuum mixer (SK-350T, Shashin Kagaku Co., Ltd.) was used. This compound served as the culture medium for growing plants and fungi. For plant seeds, they were first germinated on pre-wetted kimwipes, and the germinated seeds were then transplanted onto the compound medium for cultivation. For Aspergillus oryzae, spores were mixed directly into the compound to initiate growth. The mycorrhizal fungus spores were dispersed in the product gel, which was mixed into the compound as is. Cultivation was carried out in an incubator set at 20 °C for 5 days. For co-cultivation with mycorrhizal fungi, plant seeds were first grown for 2 weeks before inoculation.

Sintering

After cultivation of plants and fungi in the compound medium, the samples were heat-dried in an oven at 50 °C for 5.4 ks (90 min). Subsequently, sintering was performed in air using a box-type electric furnace (BF-1700-II-T, Crystal Systems). The sintering temperature was set to 1400 °C. As shown in Fig. S3, the samples were heated at a rate of 5.0 °C/min up to 1400 °C, held at this temperature for 1.8 ks (0.5 h) or 3.6 ks (1 h), and then cooled at a rate of 2.5 °C /min.

Flow test

After sintering, the obtained transparent glass samples were observed under an optical microscope. Channel cross-sections were prepared by cutting and polishing the glass chips using a grinding/polishing machine (EcoMet30, Buehler). A 0.4 w/v% trypan blue aqueous solution was injected into the open channel ends of the samples. The solution was loaded into a glass capillary and supplied to the open end using a micro-peristaltic pump (RE-C100, Aquatech). Due to surface tension, the solution entered the channel network within the sample, and its progression through the microchannels was observed under the microscope.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Melville, R. Leaf venation patterns and the origin of the angiosperms. Nature 224, 121–125 (1969).

Roth-Nebelsick, A., Uhl, D., Mosbrugger, V. & Kerp, H. Evolution and function of leaf venation architecture: A review. Ann. Bot. 87, 553–566 (2001).

West, G. B., Brown, J. H. & Enquist, B. J. A general model for the structure and allometry of plant vascular systems. Nature 400, 664–667 (1999).

Sack, L. & Scoffoni, C. Leaf venation: Structure, function, development, evolution, ecology and applications in the past, present and future. New Phytol. 198, 983–1000 (2013).

Pries, A. R., Secomb, T. W., Gaehtgens, P. & Gross, J. F. Blood flow in microvascular networks. Exp. Simul. Circ. Res. 67, 826–834 (1990).

LaBarbera, M. Principles of design of fluid transport systems in zoology. Science 249, 992–1000 (1990).

West, G. B., Brown, J. H. & Enquist, B. J. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science 276, 122–126 (1997).

Lee, A. et al. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science 365, 482–487 (2019).

Tien, J. & Dance, Y. W. Microfluidic biomaterials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001028 (2021).

Golden, A. P. & Tien, J. Fabrication of microfluidic hydrogels using molded gelatin as a sacrificial element. Lab Chip 7, 720–725 (2007).

Miller, J. S. et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat. Mater. 11, 768–774 (2012).

Kim, S., Lee, H., Chung, M. & Jeon, N. L. Engineering of functional, perfusable 3D microvascular networks on a chip. Lab Chip 13, 1489–1500 (2013).

Anderson, J. R. et al. Fabrication of topologically complex three-dimensional microfluidic systems in PDMS by rapid prototyping. Anal. Chem. 72, 3158–3164 (2000).

Camp, J. P., Stokol, T. & Shuler, M. L. Fabrication of a multiple-diameter branched network of microvascular channels with semi-circular cross-sections using xenon difluoride etching. Biomed. Microdev. 10, 179–186 (2008).

Gualandi, C., Zucchelli, A., Fernández Osorio, M., Belcari, J. & Focarete, M. L. Nanovascularization of polymer matrix: Generation of nanochannels and nanotubes by sacrificial electrospun fibers. Nano Lett. 13, 5385–5390 (2013).

Bellan, L. M., Pearsall, M., Cropek, D. M. & Langer, R. A 3D interconnected microchannel network formed in gelatin by sacrificial shellac microfibers. Adv. Mater. 24, 5187–5191 (2012).

Bellan, L. M. et al. Fabrication of an artificial 3-dimensional vascular network using sacrificial sugar structures. Soft Matter 5, 1354–1357 (2009).

Huang, J.-H. et al. Rapid fabrication of bio-inspired 3D microfluidic vascular networks. Adv. Mater. 21, 3567–3571 (2009).

Tokumaru, K., Tsumori, F., Kudo, K., Osada, T. & Shinagawa, K. Development of multilayer imprint process for solid oxide fuel cells. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 06GL04 (2017).

Taira, R. & Tsumori, F. Submicron imprint patterning of compound sheet with ceramic nanopowder. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61, 1011 (2022).

Tokumaru, K., Yonekura, K. & Tsumori, F. Imprint process with in-plane compression method for bio-functional surface. J. Photopolymer Sci. Technol. 32, 315–319 (2019).

Taira, R. & Tsumori, F. Fabrication of micro/submicron hierarchical structures on ceramic sheet surfaces combining 2-step imprinting and in-plane compression processes. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 63, 03SP89 (2024).

Yong-Taeg, O., Fujino, S. & Morinaga, K. Fabrication of transparent silica glass by powder sintering. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 3, 297 (2002).

Yong-Taeg, O., Takebe, H. & Morinaga, K. Fabrication condition of transparent OH free sintered silica glass. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 105, 171–174 (1997).

Hiratsuka, D., Tatami, J., Wakihara, T., Komeya, K. & Meguro, T. Fabrication of transparent SiO2 glass from pressureless sintering of floc-cast green body in air. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 115, 392–394 (2007).

Ikeda, H., Fujino, S. & Kajiwara, T. Fabrication of micropatterns on silica glass by a room-temperature imprinting method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 2319–2322 (2011).

Kotz, F. et al. Three-dimensional printing of transparent fused silica glass. Nature 544, 337–339 (2017).

Kotz, F. et al. Fabrication of arbitrary three-dimensional suspended hollow microstructures in transparent fused silica glass. Nat. Commun. 10, 1439 (2019).

Kotz, F. et al. Two-photon polymerization of nanocomposites for the fabrication of transparent fused silica glass microstructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006341 (2021).

Koga, T. & Tsumori, F. Fabrication of glass microchannels using plant roots and nematodes. J. Photopolymer Sci. Technol. 35, 219–223 (2019).

Nakashima, S. et al. Developing a method of fabricating microchannels using plant root structure. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 06HJ07 (2018).

Murray, C. D. The physiological principle of minimum work applied to the angle of branching of arteries. J. Gen. Physiol. 9, 835–841 (1926).

Durand, M. Architecture of optimal transport networks. Phys. Rev. E 73, 016116 (2006).

McCulloh, K. A., Sperry, J. S. & Adler, F. R. Water transport in plants obeys Murray’s law. Nature 421, 939–942 (2003).

Bejan, A. & Lorente, S. Constructal theory of generation of configuration in nature and engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 041301 (2006).

Nava-Arriaga, E. M., Hernandez-Guerrero, A., Luviano-Ortiz, J. L. & Bejan, A. Heat sinks with minichannels and flow distributors based on constructal law. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 125, 105122 (2021).

Cassot, F., Lauwers, F., Fouard, C., Prohaska, S. & Lauwers-Cances, V. A novel three-dimensional computer-assisted method for a quantitative study of microvascular networks of the human cerebral cortex. Microcirculation 13, 1–18 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Admatechs Co., Ltd. for their generous support in providing the silica nanopowder samples that made this research possible.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS Kakenhi Grant Number JP19K21922 and MEXT Kakenhi Grant Number JP21H00371.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. and S.N. contributed equally as co-first authors. They performed the experiments related to cultivation and glass chip fabrication processes. S.N. completed the fundamental fabrication process. T.K. conducted the fluid flow testing experiments. F.T. proposed the original concept, provided guidance to T.K. and S.N., analyzed the experimental data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethical standards

Experimental research on cultivated plants, including the use of plant material, complies with relevant institutional and national guidelines and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koga, T., Nakashima, S. & Tsumori, F. Replicating biological 3D root and hyphal networks in transparent glass chips. Sci Rep 14, 21128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72333-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72333-y

This article is cited by

-

Geometric determinants of sinterless, low-temperature-processed 3D-nanoprinted glass

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2025)