Abstract

Enhancement of plant growth at early growth stages is usually associated with the stimulation of various metabolic activities, which is reflected on morphological features and yield quantity and quality. Vitamins is considered as anatural plant metabolites which makes it a safe and ecofriendly treatment when used in appropriate doses, for that this research aimed to study the effect of two different vitamin B forms (thiamine and pyridoxine) on Vicia faba plants as agrowth stimutator in addition to study it’s effect on plant as astrong antioxidant under salinity stress.Our findings demonstrated that both vitamin forms significantly increased seedling growth at germination and early growth stages, especially at 50 ppm for pyridoxine and 100 ppm for thiamine. Pyridoxine at 50 ppm increased seedling length by approximately 35% compared to control, while thiamine at 100 ppm significantly promoted seedling fresh and dry wt by 4.36 and 1.36 g, respectively, compared to control seedling fresh wt 2.17 g and dry weight 1.07 g. Irrigation with 100 mM NaCl had a negative impact on plant growth and processes as well as the uptake of several critical ions, such as K+ and Mg+2, increasing Na uptake in comparison to that in control plants. Compared to control plants irrigated with NaCl solution, the photosynthetic pigments, soluble sugars, soluble proteins, and total antioxidant capacity increased in the presence of pyridoxine and thiamine, both at 50 and 100 ppm salinity. The proline content increased in both treated and untreated plants subjected to salt stress compared to that in control plants. Thiamine, especially at 50 ppm, was more effective than pyridoxine at improving plant health under saline conditions. An increase in Vicia faba plant tolerance to salinity was established by enhancing antioxidant capacity via foliar application of vitamin B through direct and indirect scavenging methods, which protect cell macromolecules from damage by oxidative stress, the highest antioxidant capacity value 28.14% was recorded at 50 ppm thiamine under salinity stress.The provided results is aguide for more researches in plant physiology and molecular biology to explain plant response to vitamins application and the suggest the sequence by which vitamins work inside plant cell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Broad bean or faba bean (Vicia faba) is an important edible crop in Egypt. It was first cultivated and utilized as a human food and stock feed in North Africa and Southwest Asia, where it is a member of the Fabaceae family1. Currently, faba beans are grown practically everywhere in the world. Most agricultural research focus on enhancing plant growth and productivity or helping plants adapt to various conditions2. The nutritional, agronomic, and financial benefits of faba beans are receiving increasing amounts of attention. This legume has a high protein content and a well-balanced amino acid profile,with the exception of low levels of methionine and cysteine3. However, lysine is particularly abundant4. Additionally, it is a plentiful source of additional healthy nutrients, such as dietary fibers5, ash6, and phenolic compounds2,7. Due to its reduced endogenic lipoxygenase activity8 and low lipid content9, faba beans are also less likely to acquire off tastes than soybeans and peas.

One of the most common abiotic stresses affecting plant physiology is salinity, caused by increase of NaCl concentration in soil10,11,12. Several plant problems (nutrient ion imbalance, reduction in stomatal conductance, and reduced photosynthetic activity) are caused by salt stress13,14. Osmotic stress, causes toxicity by increasing Na + and Cl- ions concentrations as well as increasing ROS production that cause oxidative stress15, secondary metabolite alterations (signal molecules, hormones, and oxidant chemicals), as well as morphological alterations (decreases in leaf number, plant size, root length, and fruit output)12,16. According to several studies on various plants, NaCl stress decreases plantsfresh and dry weights of roots and shoots17,18,19,20.

Vitamins play a crucial role in both plant and animal metabolism; hence, supplementation with vitamin B in various forms may be a suitable first step in increasing plant tolerance to abiotic conditions such as salt. Because of their redox chemistry, role as cofactors, and strong antioxidant potential21,22,23,24,25,26. Studies on the application of vitamin B forms on plants is not enough and more researches are needed in this point to explain it’s vital role in plant and make use of it in agriculture field.

Thiamine, also known as vitamin B1, was the first vitamin B identified27. Free thiamine, thiamine monophosphate (TMP) and thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) are the three most predominant forms of B1 that exist in cells28.

Thiamine is a colorless, water-soluble vitamin that is predominantly produced by plants and microorganisms and is crucial for human nutrition29.Thiamine is widely distributed across plant organs, namely, leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, roots, tubers and bulbs21. Thiamine pyrophosphate, the cofactor form of vitamins, is by far the most prevalent form of vitamin B1 in plants. It is a crucial component required in many metabolic activities, such as acetyl-CoA biosynthesis, amino acid biosynthesis, the Krebs cycle, and the Calvin cycle30. Thiamine has been shown to alleviate the effects of several environmental stresses on Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), presumably by protecting the plant from oxidative damage31. Because oxidative stress is required for the renewal of antioxidants such as glutathione and ascorbate, thiamine may indirectly function as an antioxidant in plants by supplying NADH and NADPH to counteract these conditions21,32,33 also play a significant role in the transketolation processes of the pentose phosphate cycle, which provides pentose phosphate for nucleotide synthesis and produces the reduced form of NADP required for several metabolic pathways34,35. However, thiamine also functions as a coenzyme in the decarboxylation of keto acids such as pyruvic acid and keto-glutamic acid and plays a role in carbohydrate and fat metabolism30. Thiamine is a powerful scavenger of superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals36 that helps in protecting membranes from lipid peroxidation. Numerous studies have revealed that the application of thiamine to plants increases their vegetative growth and chemical content. The growth of mustard plants was significantly accelerated by soaking seeds in thiamine hydrochloride.

Thiamine builds up in plants under various abiotic conditions, and its exogenous administration confers a degree of tolerance to salt and oxidative stresses23,37. Indeed, Sayed and Gadallah38 demonstrated that the beneficial effects of thiamine administered topically to shoots or subcutaneously to roots of sunflower plants were offset by salt stress. In comparison to those of untreated plants, thiamine-treated plants under salt stress presented higher chlorophyll levels, greater relative water contents, lower leaf water potential, higher concentrations of soluble sugars and total free amino acids, lower concentrations of Na+, Ca+2, and Cl-, and higher concentrations of K+. This finding is in agreement with the findings of Fallahi et al.39, who showed that foliar thiamine spraying, particularly at a concentration of 750 M, improved vegetative growth, leaf nutrient content (N, P, and Ca+2), and chlorophyll content in basil plants. The same results were also observed in Vicia faba40, Oryza sativa41, and Lupinus termis42. Similarly, research on maize showed that foliar application of thiamine (100 ppm) increased the number of green leaves, the leaf area index (LAI), and postponed leaf senescence. In comparison to the corresponding control, thiamine also increased the antioxidant capacity43.

Vitamin B6 comprises a group of compounds that include pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine, and their phosphorylated derivatives. All organisms require the important metabolite pyridoxine (vitamin B6) in its active form, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate44. Numerous metabolic enzymes may utilize it as a coenzyme, and recent research has revealed that it is also an effective antioxidant45. A de novo synthesis pathway for vitamin B6 exists in both plants and microbes. It has been found that some plant species need it for growth and differentiation46.

Foliar treatment may be a useful option for these plants since, while certain plant species’ roots can synthesize vitamin B, the roots of other plant species cannot47 and are dependent on transfer from the shoot48. Many metabolic enzymes, such as those involved in the metabolism of amino acids and the production of antibiotics, are crucial cofactors. The pyridoxine (vitamin B6) concentration increased to some extent (1750 mg) according to Mahdi et al.49.Desouky50 and Hamada and Khulaef40 showed that soaking Vicia faba seeds in pyridoxine (vitamin B6) stimulated both photosynthetic pigment and the net photosynthetic rate. Similarly, Khan et al.51 noted that applying vitamin B6 to wheat plants at a particular limit resulted in the highest increase in growth parameters.

The objective of this study was to assess the physiological impact of two forms of vitamins (B) thiamine and pyridoxine, on Vicia faba vegetative growth under salt stress in order to improve plant tolerance to stress.

Materials and methods

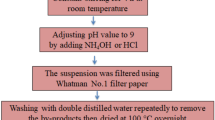

In March 2022, a pot experiment established at the Helwan University farm. Broad bean seeds were supplied by Egypt’s Giza Agricultural Research Centre. First, a preliminary experiment was performed on bean seeds to study the response to a wide range of pyridoxine and thiamine concentrations. Seeds were soaked in pyridoxine and thiamine (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 ppm) for 12 h and subsequently sown in small pots filled with clay, with 6 replicates for each treatment and five seeds per pot. After 2 weeks,the seedling length and fresh and dry weights were measured. From these preliminary experimental results, the most effective concentrations were selected for the pilot experiment. In pots filled with loamy soil, uniform bean seeds were planted, and 21 days after planting, the plants were divided into two groups: one group was irrigated with tap water, and the other group was irrigated with 100 mM NaCl solution. The plants in each group were divided into five subgroups (Fig. 1), each represented by five pots containing three seedlings. Pyridoxine and thiamine were applied as foliar sprays twice on the leaves at 50 and 100 ppm, and distilled water was applied as a foliar spray for controls.

Growth criteria

Two weeks after the last foliar spray, the stem and root length, shoot and root fresh and dry weights and number of leaves were recorded, and samples were taken for chemical analysis.

Photosynthetic pigment content

The method of Metzener et al.52 was used to assess the photosynthetic pigment content in faba bean leaves. The concentrations of chlorophyll a and b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids were calculated using the following equations:

Chl. a = 10.3 E664- 0.918 E645.

Chl. b = 19.7E645-3.87E664.

Total chlorophyll (a + b) = Chl a + Chl b.

Carotenoids = 4.3 E452 (0.0265 Chl.a + 0.426 Chl.b).

Total soluble sugars

As described by Umbriet et al.53,theanthrone approach was used to measure the total amount of soluble sugars. Three milliliters of sample was treated with six milliliters of anthrone solution (2 g/L H2SO4 95%) and kept in a boiling water bath for three minutes.After cooling, the generated color was spectrophotometrically measured at 620 nm.

Total soluble proteins

Total soluble protein was measured according to the methods of Lowry et al.54. Briefly, 2% sodium carbonate in 4% sodium hydroxide, 0.5% copper sulfate in 1% sodium tartrate, and 1 ml of faba bean extract were combined in a freshly mixed solution (50:1 v/v). After standing for 10 min, the mixture was diluted to a specific volume with 0.5 ml of Folin-Phenol reagent (1:3). After 30 min, the optical density of the mixture was measured at 750 nm.

Proline

Ten milliliters of sulfo-salicylic acid (3%) was used to homogenize approximately 0.5 g of faba bean leaves before filtering the mixture using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Using the technique outlined by Bates et al.55, free proline was measured. From a standard curve, the proline concentration was calculated as mg proline/g dry weight.

Phosphomolybdenum assay

The antioxidant activity of the fractions was assessed using the phosphomolybdenum method following the methods of Prieto et al.56. One milliliter of the reagent solution (0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate) was added to an aliquot of 0.1 ml of each fraction that had been dissolved in its corresponding solvent. The vial was sealed and left to sit at 95 ℃ in a water bath for 90 min. The samples were cooled to room temperature after incubation, and the absorbance of the mixture at 765 nm was measured in comparison to that of the control. The following formula was used to determine the percent inhibition, and the software Graph Prism Pad was used to determine the IC50.

% inhibition = (1– absorbance of sample/absorbance of control) × 100.

Mineral ions

A 15 ml acid mixture of HNO3: HCl (1:1, v/v) was used to digest approximately 0.5 g of oven-dried leaves, and the digest was heated on a hot plate until it was clear. The digest was double deionized water diluted to 25 ml, cooled, and filtered. At the Ecology Lab, Helwan University’s Faculty of Science, phosphorus, potassium, sodium and magnesium concentrations were measured using microwave plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (Agilent Technologies 4210 MP-AES). Mineral ions were expressed as ppm on a dry matter basis.

Statistical analysis

The least significant difference (LSD at the 5% level) was used to determine statistical significance for the compared means via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple comparison test using IBM Statistical Version 21.

Results

The preliminary experiment results (Table 1 and Fig. 2) showed that soaking faba beans seeds in pyridoxine at concentrations up to 250 ppm and thiamine at concentrations up to 200 ppm significantly improved the growth criteria of bean plants, represented by shoot and root length and fresh and dry weight. Compared with corresponding control plants, the most effective concentrations of both vitamin B forms were 50 and 100 ppm. Pyridoxine at 50 ppm was more effective than thiamine at increasing seedling length by approximately 35%, while thiamine at 100 ppm significantly promoted seedling fresh and dry wt by 4.36 and 1.36 g, respectively, compared to that of the control seedling fresh wt 2.17 g and dry weight 1.07 g.

The main pot experiment data presented in Table 2 show that, compared to control plants, the tested pyridoxine and thiamine concentrations increased all the measured growth parameters in Vicia faba,represented by stem and root length;the fresh and dry weights of shoots and roots; and the number of leaves. The highest growth parameters were recorded for 100 ppm thiamine, followed by 50 ppm pyridoxine. Salinity negatively affected the morphological growth of Vicia fabaplants compared to the corresponding control plants. In addition to the promotive effect of vitamins under normal conditions, there was a significant increase in all growth criteria under salt stress compared to those in untreated salt-stressed plants.

Foliar spraying with vitamin B alleviated the negative effect of salinity on essential ion uptake and controlled the uptake of Na+ ions. Thiamine and pyridoxine foliar sprays on Vicia faba enhanced the absorption of the mineral ions Mg andK, while the sodium uptake decreased in these plants compared to that in untrated plants affected by salinity.The best concentration was 100 ppm for both vitamin B forms (Table 3).

The data presented in Fig. 3 show that salinity decreased the total photosynthetic pigment content (1.15 mg g−1d.m.) compared to the corresponding control (1.49 mg g−1d.m.). The application of pyridoxine and thiamine at 50 and 100 ppm increased the chlorophyll a, b and carotenoid contents in faba bean leaves under normal and salt-stressed conditions, especially at 50 ppm thiamine in both normal plants and plants subjected to salinity stress (1.73 and 1.6 mg g−1d.m.), respectively.

Effect of two different vitamin B forms: Py (Pyridoxine) Th (Thiamine) on Total photosynthetic pigment of Vicia faba plant grown under salinity stress. Values represent the mean of three replicates. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e and f) indicate statistical differences at 5% probability according to Duncan’s test. Error bars are standard errors of the mean.

The effect of salinity on photosynthetic pigments is strongly related to plant primary metabolites and the ratio of soluble to insoluble contents in plants. Soluble sugars and proteins accumulated under saline conditions in faba bean leaves compared to those in control plants. In addition, vitamin B in both forms significantly increased the soluble sugar and protein contents compared to those of the control and untreated salt-stressed plants. The highest content was recorded at 50 ppm thiamine in normal and salt-stressed plants (10.56 and 12.4 mg g−1d.m soluble sugars) and (147.57 and 183.33 mg g−1d.m for soluble proteins) (Fig. 4). Proline, also known as a stress marker, increased under 100 mM NaCl. Vitamin B in both forms helped plants overcome stress, and there was a significant decrease in proline content (Fig. 5A). The lowest proline content was 0.55 g−1d.m at 100 ppm thiamine under normal conditions compared to that in control plants 0.65 g−1d.m. Treatment decreased the proline content in the salt-stressed plants from 0.76 g−1d.m to approximately the same level as that in the control leaves.

Effect of two different vitamin B forms : Py (Pyridoxine) Th (Thiamine) on (A) total soluble sugars and (B) total soluble protein contents of Vicia faba plant grown under salinity stress. Values represent the mean of three replicates. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e, f an g) indicate statistical differences at 5% probability according to Duncan’s test. Error bars are standard errors of the mean.

Effect of two different vitamin B forms on : Py (Pyridoxine) Th (Thiamine) (A) Proline content and (B) Total antioxidant capacity % of Vicia faba plant grown under salinity stress. Values represent the mean of three replicates. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e and f) indicate statistical differences at 5% probability according to Duncan’s test. Error bars are standard errors of the mean.

Total antioxidant capacity is an important screen for evaluating plant tolerance. Under salinity, the total antioxidant capacity increased to 22%, whereas it was 19.4% for control plants. After foliar application of both thiamine and pyridoxine, the antioxidant capacity increased both under normal conditions and under 100 mM NaCl, with the highest value reaching 28.14% recorded at 50 ppm thiamine (Fig. 5B). Both vitamin B forms helped Vicia faba plants tolerate salinity, while thiamine was more effective than pyridoxine.

Discussion

Vitamins use in maintenance of plant growth, development and adaptation may be asuitable solution in agriculture for many severe problems affecting plants productivity nowadays. Pyridoxine and thiamine significantly promoted vicia faba growth at both early seedling stage and vegetative growth under both normal and salt stress conditions. The findings of the present study on vicia faba plant are in agreement with those of prior research showing Na toxicity in wheat55, Pisum sativum L.56, vicia faba57, chickpea species58,and Oenanthe javanica species59. Increased Na+ and Cl- concentrations in plants are a result of soil salinity, which also affects the ratio of Na+/K+ and the regular ionic activities of plants60. This increase in osmotic stress decrease water uptake and transport. The hormone-induced sequential responses that result from water uptake inhibition might decrease stomatal opening, carbon dioxide assimilation, and the photosynthetic rate60,61. A decrease in nitrate reductase activity, inhibition of photosystem II62, and chlorophyll breakdown63,64 have been also observed. A reduction in the efficiency of photosynthesis and carbon gains and a shift in energy from growth to the homeostasis of salt stress could also contribute to a decrease in growth59,63. Photosynthesis is impacted by high NaCl concentrations, and longer-term salt stress reduces the production of the chlorophyll protein-lipid complex65.

Salinity reduces the production of new proteins that connect chlorophyll by enhancing the activity of the enzyme chlorophyllase66. During this process, K + is a known enzyme stimulant for a number of photosynthesis-related enzymes. Therefore, decreases in K + levels prevent photosynthesis, which ultimately results in decreased growth67. In addition to increasing antioxidant capacity through enzymatic and nonenzymatic mechanisms, plants overcome oxidative damage by accumulating osmoregulatory and osmoprotectants such as soluble sugars and soluble proteins such as proline, which are key stress markers. This enables plants to tolerate stress and protects them from harm caused by unchecked ROS production.

Vitamins are regarded as vital antioxidants in plants, and exogenous vitamin administration may work in conjunction with endogenous vitamin levels to help plants withstand and respond to environmental challenges. Vitamins had positive effects on plant nutrition, and growth certainly influenced the yield of the components. Mainly vitamin B positive effect is generally related to it’s high antioxidant and protective role on plant macromolecules, improvemevt of chlorophyll content, hormonal and nutrient balance, all these effects improves plant metabolism during seed germination and vegetative growth.

B-group vitamins are quite effective at increasing ion absorption68. Similar findings were made by Youssef and Talaat69, who reported that foliar thiamine enhanced the contentof total nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in rosemary plants. Thiamine applied topically to leaves has been shown to help mustard plants better absorb nitrogen70. Abd El-Aziz et al.71 also stated an increase in phosphorus and nitrogen uptake. The function of thiamine in dividing meristematic stem cells and organ starting cells may be related to its role in promoting basal growth and seed development, according to Martinis et al.72.In addition, it plays a role in the growth and division of cells, the production of nucleic acids, and the control of the assimilation of carbon73. Thiamine may protect cell membranes and their binding transporters, which leads to increased absorption and translocation of minerals38,74. In addition, an increase in nutrient solubility in the rhizosphere of vitamin-treated plants through the secretion of organic acids into the soil is another reason for increased nutrient uptake by the plant71.

A notable increase in plant height, biomass and chlorophyll content was observed in wheat by thiamine application both under control and water stress conditions. Moreover, reduction in oxidative stress markers viz., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), malondialdehyde and electrolyte leakage was found with thiamine application under stress. In addition, cellular antioxidants, mineral contents and yield attributes were also enhanced by thiamine application especially at 100 mg/L under water stress75 the same result was repoted on Pisum sativum L. at 250, 500 ppm76.

According to Kaya et al.77, increased growth in plants treated with thiamine is linked to decreased membrane ermeability; decreased malondialdehyde (MDA) and H2O2 levels; altered antioxidant enzyme activities, such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and peroxidase; and increased photosynthetic pigment and PSII activity. Exogenous thiamine administration increased antioxidant enzyme activity in Gerbera jamesonii, according to Mansouri et al.78. The results reported by Abdel-Monaim et al.79 on soybeans demonstrated that plants treated with thiamine and riboflavin had higher antioxidant enzyme activity than controls, including peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, and phenylalanine ammonia lyase. These findings could be explained by the function of thiamine in a number of metabolic pathways, including photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and sugar and protein metabolism.Thi application counteracts the inhibitory effect of ROS on chlorophyll content77. The promotion of carotenoid synthesis as a protector of chlorophyll against oxidation by Thi is another reason for the increase in chlorophyll concentration in plants treated with Thi41. Moreover, the overexpression of the 2-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate enzyme, which is strongly dependent on Thi-diphosphate, correlates with the accumulation of chlorophyll31.

Thiamine may lead to an increase in the accumulation of certain osmoregulatory agents in plant tissues, which may have an impact on water potential and, in turn, may increase the turgor pressure required for cell expansion and, ultimately, plant development38. Additionally, proper regulation of photosynthesis and energy generation is purportedly responsible for the improved growth and yield of plants treated with thiamine72. Under different abiotic stress the effect of thiamine also was reported, thiamine acid application improves length, biomass, leaf area, photosynthetic pigment and mineral nutrition, and reduces H2O2, Na, and Pb accumulation in roots and shoots under lead stress80.

Researches on the effect of pyridoxine on plant are limited compared to thiamine. Dalatabadian and Modarressanavy81 reported that growing sunflower plants with pyridoxine concentrations up to 400 ppm resulted in a significant increase in plant dry weight. It appears that pyridoxine also plays a significant role in cell division. Asli and Houshmandfar82 reported that soaking seeds in pyridoxine solution might enhance the growth of maize plants. Mahdi et al.49 also reported that the application of pyridoxine (vitaminB6) at a certain concentration (1750 mg. L-1can protect wheat plants and increase their resistance to salinity stresses.Treatment of wheat plants with pyridoxine improved cell division, root growth, and nutrient uptake, which improved the efficiency of the photosynthetic surface and increased the formation of dry matter. Additionally, according to Hamada and Khulaef40, pyridoxine seed pretreatment and foliar treatments of beans increased the biosynthesis of photosynthetic pigment fractions. Additionally, Hendawy and Ezz El- Din83 and Nassar et al.84 both supported the elevated levels of photosynthetic pigments found in Foeniculum vulgare var. azoricum and sesame plants. The endogenous levels of plant growth regulators have also been demonstrated to be enhanced by vitamins. Endogenous IAA and phenolic levels were markedly elevated by exogenous therapy, such as foliar spraying of thiamine vitamin on lupine plants. These increases could be attributed to pyridoxine’s role in IAA production and its ability to slow the breakdown of the compound85. In general, the improvements in ion uptake, growth promoter levels, protection of photosynthetic pigments, and enhancement of plant antioxidant capacity may be the causes of the overall increase in plant vegetative growth caused by the application of vitamin B. All these processes control and regulate plant photosynthetic capacity, which is the primary source of all macromolecules used in plant adaptation to stress.

Osmoregulation is one of the most significant strategies for adapting to salt stress. According to our findings, during salt stress, soluble sugar and protein concentrations in faba bean plants increase with both vitamin types. Reduced photosynthetic pigments caused by salinity have an impact on the generation of sugars during photosynthesis. Instead of growing more, certain tolerant plants store soluble carbohydrates and proteins as an osmoprotectant mechanism to boost water intake and prevent harm from high salt concentrations in soil. In addition to serving as ROS scavengers, these solutes may be crucial storage carbon and nitrogen supplies86.

By promoting osmosis in the cytoplasm, balancing proteins and membranes, and maintaining higher water levels needed for plant growth and cell activities, osmoprotectants (total soluble sugars, proline, and free amino acids) significantly impact how well cells adapt to varying unfavorable environmental stresses. An increased TSS enhances cell membrane maintenance and turgor maintenance. The accumulation of proline and soluble sugars under stress conditions protects cells by maintaining the osmotic strength of the cytosol in combination with that of vacuoles and the external environment. In addition to its osmoprotective role, proline is commonly used as a ROS scavenger and provides protection to enzymes and stabilizes their structures87,88. Proline accumulation is suggested to be a symptom of stress in various plants, acting as an osmotic barrier and assisting in cell turgor stability89. Free amino acid buildup associated with stress can be a part of the adaptive technique that assists with osmotic equilibrium.

Conclusion

Vicia faba is an economically important plant that is sensitive to salinity stress, which is one of the main abiotic factors affecting plant productivity. Increased plant resistance to salt stress may increase the use of agricultural land, which is frequently exposed to high salt concentrations while overcoming yield loss. In addition to improving plant tolerance and yield quality and quantity. Vitamins such as vitamin B(thiamine and pyridoxine) are safe, affordable and inexpensive to farmers. Both vitamin forms improved bean plant growth especially at 50 and 100 pm leading to significant increases in seed germination, vegetative plant growth; photosynthetic pigment content; sugar and protein content;and ion uptake and antioxidant capability in Vicia faba plants under normal or salt stress conditions. More physiological and genetical studies are still needed in this point to understand the effect of vitamins based on gene expression and sequence of plant adaptation steps to stress.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

L’Hocine, L., Martineau-Côté, D., Achouri, A., Wanasundara, J. P. D. & Arachchige, L. H. G. W. Broad bean (Faba bean). In Pulses (eds Manickavasagan, A. & Thirunathan, P.) (Springer, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41376-7_3.

Sadak, M. S. & Abdelhamid, M. T. Influence of amino acids mixture application on some biochemical aspects, antioxidant enzymes and endogenous polyamines of vicia faba plant grown under seawater salinity stress. Gesunde Pflanz. 67, 119–129 (2015).

Raikos, V., Neacsu, M., Russell, W. & Duthie, G. Comparative study of the functional properties of lupin, green pea, fava bean, hemp, and buckwheat flours as affected by pH. Food Sci. Nutr. 2(6), 802–810. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.143 (2014).

Hood-Niefer, S. D., Warkentin, T. D., Chibbar, R. N., Vandenberg, A. & Tyler, R. T. Effect of genotype and environment on the concentrations of starch and protein in, and the physicochemical properties of starch from, field pea and faba bean. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4552 (2012).

Çalışkantürk Karataş, S., Günay, D. & Sayar, S. In vitro evaluation of whole faba bean and its seed coat as a potential source of functional food components. Food Chem. 230, 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.03.037 (2017).

Khan, M. A. et al. Comparative nutritional profiles of various faba bean and chickpea genotypes. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 17(3), 449–457. https://doi.org/10.17957/IJAB/17.3.14.990 (2015).

Amarowicz, R. & Shahidi, F. Antioxidant activity of broad bean seed extract and its phenolic composition. J. Funct. Foods 38, 656–662 (2017).

Chang, P. R. Q. & McCurdy, A. R. Lipoxygenase activity in fourteen legumes. Can. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. J. 18(1), 94–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0315-5463(85)71727-0 (1985).

Mattila, P. et al. Nutritional value of commercial protein-rich plant products. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 73(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-018-0660-7 (2018).

Fageria, N. K., Stone, L. F. & Santos, ABd. Breeding for salinity tolerance. In Plant Breeding for Abiotic Stress Tolerance (eds Fritsche-Neto, R. & Borém, A.) (Springer, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-30553-5_7.

Rady, M. M., Sadak, M. S., El-Bassiouny, H. M. S. & Abd El-Monem, A. A. Alleviation the adverse effects of salinity stress in sunflower cultivars using nicotinamide and α-tocopherol. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 5(10), 342–355 (2011).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681 (2008).

Ivanova, K., Anev, S., Tzvetkova, N., Georgieva, T. & Markovska, Y. Influence of salt stress on stomatal, biochemical and morphological factors limiting photosynthetic gas exchange in Paulownia elongata × fortunei. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 68, 217–224 (2015).

Sadak, M. S. & Dawood, M. G. Biofertilizer role in alleviating the deleterious effects of salinity on wheat growth and productivity. Gesunde Pflanz. 75, 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-022-00783-3 (2023).

El-Mahdy, R. E., Abd El-Azeiz, E. H. & Faiyad, R. M. N. Enhancement yield and quality of faba bean plants grown under salt affected soils conditions by phosphorus fertilizer sources and some organic acids. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. Mansoura Univ 12, 89–98 (2021).

Sadak, M. S., Hanafy, R. S., Elkady, F. M. A. M., Mogazy, A. M. & Abdelhamid, M. T. Exogenous calcium reinforces photosynthetic pigment content and osmolyte. Enzym. Non Enzym. Antioxid. Abundance Alleviates Salt Stress Bread Wheat Plants 12, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12071532 (2023).

Kapoor, N. & Pande, V. Effect of salt stress on growth parameters, moisture content, relative water content and photosynthetic pigments of fenugreek variety RMt-1. J. Plant Sci. 10, 210–221 (2015).

Mahajan, M. M., Goyal, E., Singh, A. K., Gaikwad, K. & Kanika, K. Shedding light on response of Triticum aestivum cv. Kharchia local roots to long-term salinity stress through transcriptome profiling. Plant Growth Regul. 90, 369–381 (2020).

Kumar, P. et al. Salinity stress tolerance and omics approaches: Revisiting the progress and achievements in major cereal crops. Heredity 128, 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-022-00516-2 (2022).

Sadak, M. S. et al. Exogenous aspartic acid alleviates salt stress induced decline in growth b enhancing antioxidants and compatible solutes while reducing reactive oxygen species in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 987641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.987641 (2022).

Asensi-Fabado, M. & Munné-Bosch, S. Vitamins in plants: Occurrence, biosynthesis and antioxidant function. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.07.003 (2010).

Abdelhamid, M. T., Sadak, M. S., Schmidhalter, U. R. S. & El-Saady, A. M. Interactive effects of salinity stress and nicotinamide on physiological and biochemical parameters of faba bean plant. Acta Biol. Colomb. 18(3), 499–510 (2013).

El-Bassiouny, H. M. S. & Sadak, M. S. Impact of foliar application of ascorbic acid and α- tocopherol on antioxidant activity and some biochemical aspects of flax cultivars under salinity stress. Acta Biol. Colomb. 20(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.15446/abc.v20n2.43868 (2015).

El-Bassiouny, H. M. S., Sadak, M. S., Mahfouz, Sh. A., El-Enany, M. A. M. & Elewa, T. A. Use of thiamine, pyridoxine and bio stimulant for better yield of wheat plants under water stress: growth, osmoregulations, antioxidantive defence and protein pattern Egypt. J. Chem. 66(4), 407–424 (2023).

Noordally, Z. et al. The coenzyme thiamine diphosphate displays a nuclear rhythm independent of the circadian clock. Commun. Biol. 3, 209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0927-z (2020).

Fitzpatrick, T. B. & Chapman, L. M. The importance of thiamine (vitamin B1) in plant health: From crop yield to biofortification. J. Biol. Chem. 295(34), 12002–12013. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.REV120.010918 (2020).

Funk, C. The role of thiamine in plants and current perspectives in crop improvement. The etiology of the deficiency. Anal. Chim. Acta 76, 176–177 (1975).

Bettendorff, L. et al. Discovery of a natural thiamine adenine nucleotide. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 211–212 (2007).

Pourcel, L., Moulin, M. & Fitzpatrick, T. B. Examining strategies to facilitate vitamin B1 biofortification of plants by genetic engineering. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 160 (2013).

Du, Q., Wang, H. & Xie, J. Thiamin (vitamin B1) biosynthesis and regulation: A rich source of antimicrobial drug targets?. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7(1), 41–52 (2011).

Rapala-Kozik, M., Wolak, N., Kujda, M. & Banas, A. K. The upregulation of thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings under salt and osmotic stress conditions is mediated by abscisic acid at the early stages of this stress response. Plant Biol. 12(2), 1–14 (2012).

Carole, L. & Steven, C. L-Ascorbate biosynthesis in higher plants: the role of VTC2. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.005 (2008).

Raviv, A. et al. Light signaling genes and their manipulation toward modulation of phytonutrient content in tomato fruits. Biotechnol. Adv. 28, 108–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.10.003 (2009).

Yusof, Z. N. B. Thiamine and its role in protection against stress in plants (enhancement in thiamine content for nutritional quality improvement). In Nutritional Quality Improvement in Plants Concepts and Strategies in Plant Sciences (eds Jaiwal, P. et al.) (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95354-0_7.

Kartal, B. & Palabiyik, B. Thiamine leads to oxidative stress resistance via regulation of the glucose metabolism. Cell. Mol. Biol. 65(1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2019.65.1.13 (2019).

Ahn, I. P., Kim, S., Lee, Y. H. & Suh, S. C. Vitamin B1-induced priming is dependent on hydrogen peroxide and the NPR1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 143, 838–848 (2007).

SajjadSamiullah, A. Enhancement of growth and yield of mustard (Brassica Juncea L.) var. varuna by thiamine hydrochloride (Vitamin-B1) application. J. Funct. Environ. Bot. https://doi.org/10.5958/2231-1750.2015.00004.9 (2015).

Sayed, S. A. & Gadallah, M. A. A. Effects of shoot and root application of thiamin on salt-stressed sunflower plants. Plant Growth Regul. 36, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014784831387 (2002).

Fallahi, Hamid-Reza., Aminifard, Mohammadhossein & Jorkesh, Abbas. Effects of thiamine spraying on biochemical and morphological traits of basil plants under greenhouse conditions. J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. https://doi.org/10.22077/jhpr.2018.1114.1001 (2018).

Hamada, A. M. & Khulaef, E. M. Simulative effects of ascorbic acid, thiamin or pyridoxine on Vicia faba growth and some related metabolic activities. Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 3(8), 1330–1332. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2000.1330.1332 (2000).

Farouk, S., Youssef, S. A. & Ali, A. A. Exploitation of biostimulants and vitamins as an alternative strategy to control early blight of tomato plants. Asian J. Plant Sci. 11(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajps.2012.36.43 (2012).

El-Awadi, M. E., Abd Elbaky, Y. R., Dawood, M. G., Shalaby, M. A. & Bakry, B. A. Enhancement quality and quantity of lupine plant via foliar application of some vitamins under sandy soil conditions. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chemical Sci. 7(4), 1012–1024 (2016).

Sahu, M., Solanki, N. & Dashora, L. Effects of thiourea, thiamine and ascorbic acid on growth and yield of maize (Zea mays L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 171, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.1993.tb00437.x (2008).

Percudani, R. & Peracchi, A. A genomic overview of pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzymes. EMBO Rep. 4(9), 850–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.embor914 (2003).

Havaux, M. et al. Vitamin B6 deficient plants display increased sensitivity to high light and photooxidative stress. BMC Plant Biol. 9, 130 (2009).

Studart, Marina Titiz et al. Vitamin B6 biosynthesis in higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 13687–92. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506228102 (2005).

Mozafar, A. & Oertli, J. J. Uptake and transport of thiamin (vitamin B1) by barley and soybean. J. Plant Physiol. 159, 436–442 (1992).

Bonner, J. Transport of thiamin in the tomato plant. Am. J. Bot. 29, 136–142 (1942).

Mahdi, W., Ali, M., Albadry, S. & Ibrahim, I. Effect of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and saline stress on the growth and antioxidant enzymes of wheat Triticum aestivum L.. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 25, 4470–4476 (2021).

- Desouky, S. A. (1995). Effect of some organic additives on salinized Chlorella vulgaris (Doctoral dissertation, Ph. D. Thesis, Faculty of Science, Assiut University, Egypt).

Khan, M. A., Gul, B. & Weber, D. J. Seed germination characteristics of Halogeton glomeratus. Can. J. Bot. 79(10), 1189–1194 (2001).

Metzener, H., Rauand, H. & Senger, H. Unter suchungenzursynchronisierbarteiteinzelner pigment angel mutanten von Chlorella. Planta 65, 186 (1965).

Umbriet, W. W., Burris, R. H. & Stauffer, J. F. Monometric Technique, A Manual Describing Methods Applicable to the Study of Tissue Metabolism - 4th edn, 239 (Burgess Publ. Co., 1959).

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L. & Randell, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 (1951).

Hussein, M. A. A. et al. Exploring salinity tolerance mechanisms in diverse wheat genotypes using physiological, anatomical, agronomic and gene expression analyses. Plants (Basel) 12(18), 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12183330 (2023).

Khan, M. A. H. et al. Salinity-induced physiological changes in pea (Pisum sativum L.): Germination rate, biomass accumulation, relative water content, seedling vigor and salt tolerance index. Plants (Basel) 11(24), 3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11243493 (2022).

Ziche, Z. I., Belouchrani, A. S. & Drouiche, N. Study of the effect of salt stress on a legume faba bean (Vicia faba L). Gesunde Pflanz. 75, 1897–1903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-023-00857-w (2023).

Zawude, Seyoum & Shanko, Diriba. Effects of salinity stress on chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) landraces during early growth stage. Int. J. Sci. Rep. 3, 214. https://doi.org/10.18203/issn.2454-2156.IntJSciRep20173093 (2017).

Kumar, S. et al. Effect of salt stress on growth, physiological parameters, and ionic concentration of water dropwort (Oenanthe javanica) cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 660409. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.660409 (2021).

Sarker, U. & Oba, S. The response of salinity stress-induced A. tricolor to growth, anatomy, physiology, nonenzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 559876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.559876 (2020).

Menezes, R. V., Azevedo Neto, A. D. D., Ribeiro, M. D. O. & Cova, A. M. W. Growth and contents of organic and inorganic solutes in amaranth under salt stress. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 47, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632016v4742580 (2017).

Orcutt, D. M. & Nilsen, E. T. The Physiology of Plants under Stress: Soil and Biotic Factors (New York, 2000).

Anbazhagan, K. R. M. & Bhagwat, K. A. Effect of NaCl toxicity of chlorophyll breakdown in rice. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 57, 567–570 (1987).

Bose, Jayakumar et al. Chloroplast function and ion regulation in plants growing on saline soils: Lessons from halophytes. J. Exp. Bot. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erx142 (2017).

GhogdiE, A., Izadi-Darbandi, A. & Borzouei, A. Effects of salinity on some physiological traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 5, 1901–1906. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2012/v5i1.23 (2012).

Jaleel, C. A. et al. Alterations in os-moregulation, antioxidant enzymes and indole alkaloid levels in Catharanthus roseus exposed to water deficit. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 59, 150–157 (2007).

Cui, J. & Tcherkez, G. Potassium dependency of enzymes in plant primary metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 166, 522–530 (2021).

Rao, D. R., Reddy, A. V., Pulusani, S. R. & Cornwell, P. E. Biosynthesis and utilization of folic acid and vitamin B12 by lactic cultures in skim milk. J. Dairy Sci. 67(6), 1169–1174 (1984).

Youssef, A. A. & Talaat, I. M. Physiological response of rosemary plants to somevitamins. Egypt. Pharm. J. 1, 81–93 (2003).

Sajjad, Y., Jaskani, M. J., Qasim, M., Akhtar, G. & Mehmood, A. Foliar application of growth bioregulators influences floral traits, corm associated traits and chemical constituents in Gladiolus grandiflorus L. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 33(6), 812–819 (2015).

Abd El-Aziz, N. G., El-Quensi, F. E. M. & Farahat, M. M. Response of vegetative growth and some chemical constituents of Syngonium podophyllum L. to foliar application of thiamine, ascorbic acid and kinetin at Nubaria. World J. Agric. Sci. 3(3), 301–305 (2007).

Martinis, J. et al. Long-distance transport of thiamine (vitamin B1) is concomitant with that of polyamines. Plant Physiol. 171, 542–553 (2016).

Andrew, W. J., Youngkoo, C., Chen, X. & Pandalai, S. G. Vicissitudes of a vitamin. Recent Res. Dev. Phytochem. 4, 89–98 (2000).

Mady, M. A. Effect of foliar application with salicylic acid vitamin E on growth and productivity of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants. J. Agric. Sci. Mansoura Univ. 34(6), 6735–6746 (2009).

Bashir, R. et al. Thiamine (vitamin B1) helps to regulate wheat growth and yield under water limited conditions by adjusting tissue mineral content, cytosolutes and antioxidative enzymes. Plant Growth Regul. 101, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-023-01045-6 (2023).

Kausar, A. et al. Alleviation of drought stress through foliar application of thiamine in two varieties of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Plant Signal Behavior 18(1), 2186045. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2023.2186045 (2023).

Kaya, C. et al. Exogenous application of thiamin promotes growth and antioxidative defense system at initial phases of development in salt-stressed plants of two maize cultivars differing in salinity tolerance. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37, 1–12 (2015).

Mansouri, M., Shoor, M., Tehranifar, A. & Selahvarzi, Y. The effect of foliar application of salicylic acid and thiamine on the biochemical characteristics of Gerbera jamesonii cv. Pink elegance. J. Hortic. Sci. 29(1), 127–133 (2015).

Abdel- Monaim, M. F. Role of riboflavin and thiamine in induced resistance against charcoal rot disease of soybean. African J. Biotechnol. 10(53), 10842–10855 (2011).

Bouhadi, M. et al. Exogenous application of thiamine and nicotinic acid improves tolerance and morpho-physiological parameters of lens culinaris under lead (Pb) exposure. J. Plant Growth Regul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-024-11383-y (2024).

Dolatabadian, A. & SANAVY, S. A. M. M. Effect of the ascorbic acid, pyridoxine and hydrogen peroxide treatments on germination, catalase activity, protein and malondialdehyde content of three oil seeds. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj Napoca 36(2), 61–66 (2008).

Asli, D. E. & Alireza Houshmandfar, A. Seed Germination and Early Seedling Growth of Corn (Zea Mays L.) As Affected by Different Seed Pyridoxine-priming Duration. (2011). https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Seed germination and early seedling growth of corn (Zea Mays L.) as...-a0256863987. Accessed 13 Sep 2024.

Hendawy, S. & Ezz, A. Growth and yield of Foeniculum vulgare var.azoricum as influenced by some vitamins and amino acids. Ozean J. Appl. Sci. 3, 113–123 (2010).

Nassar, R., Arafa, S. & Farouk, S. Effect of foliar spray with pyridoxine on growth, anatomy, photosynthetic pigments, yield characters and biochemical constituents of seed oil of sesame plant (Sesamum indicum L.). Middle East J. Appl. Sci. 7, 80–91 (2017).

Sadak, M. S. Physiological role of arbuscular mycorrhizae and vitamin B1 on productivity and physio-biochemical traits of white lupine (Lupinus termis L.) under salt stress. Gesunde Pflanz. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-023-00855-y (2023).

Paliwal, Ashutosh et al. Effect and Importance of Compatible Solutes in Plant Growth Promotion under Different Stress Conditions (Springer, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80674-3_10.

Rahneshan, Z., Nasibi, F. & Moghadam, A. A. Effects of salinity stress on some growth, physiological, biochemical parameters and nutrients in two pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) rootstocks. J. Plant Interact. 13, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2018.1424355 (2018).

Alzahrani, S. M. et al. Physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant properties of two genotypes of Vicia faba grown under salinity stress. Pak. J. Bot. 51, 786–798. https://doi.org/10.30848/PJB2019-3(3) (2019).

Strizhov, N. et al. Differential expression of two P5CS genes controlling proline accumulation during salt-stress requires ABA and is regulated by ABA1, ABI1 and AXR2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 12, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.00557.x (1997).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors participated in practical work and wrote and revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, E.Z., Sattar, A.M.A.E. Improvement of Vicia faba plant tolerance under salinity stress by the application of thiamine and pyridoxine vitamins. Sci Rep 14, 22367 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72511-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72511-y