Abstract

Diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome are closely linked with visceral body composition, but clinical assessment is limited to external measurements and laboratory values including hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Modern deep learning and AI algorithms allow automated extraction of biomarkers for organ size, density, and body composition from routine computed tomography (CT) exams. Comparing visceral CT biomarkers across groups with differing glycemic control revealed significant, progressive CT biomarker changes with increasing HbA1c. For example, in the unenhanced female cohort, mean changes between normal and poorly-controlled diabetes showed: 53% increase in visceral adipose tissue area, 22% increase in kidney volume, 24% increase in liver volume, 6% decrease in liver density (hepatic steatosis), 16% increase in skeletal muscle area, and 21% decrease in skeletal muscle density (myosteatosis) (all p < 0.001). The multisystem changes of metabolic syndrome can be objectively and retrospectively measured using automated CT biomarkers, with implications for diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and GLP-1 agonists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome, also known as insulin resistance syndrome, affects an increasing proportion of the population, including more than 1 in 3 adults in the United States1. Metabolic syndrome is a multisystem condition that increases the risk for many serious health conditions including heart disease, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy complications, and immune system disorders2,3. There are several definitions of metabolic syndrome with small variations in diagnostic criteria, but an association with body composition is a consistent major diagnostic criterion based on external anthropometric proxy measurements such as waist circumference, waist/hip ratio, or body mass index (BMI) which are not direct measurements of body composition2,3,4. Additional major diagnostic criteria include insulin resistance, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia. The World Health Organization definition included microalbuminuria as a separate criterion, requiring urinalysis and implicitly adding renal dysfunction to the major criteria5. Of note, although measurements of visceral and ectopic fat depots (e.g., hepatic steatosis and myosteatosis) are highly relevant to metabolic syndrome, they are not included in current diagnostic criteria but can be assessed at cross-sectional imaging6.

The clinical biomarkers of metabolic syndrome are widely available through external measurements or routine laboratory studies. Insulin resistance is typically assessed with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, but once patients are diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, they are typically followed by the measurement of glycosylated serum hemoglobin or Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). HbA1c is a commonly available serum laboratory test that monitors the proportion of glycosylated hemoglobin carried by red blood cells (RBCs). The constant turnover in red blood cells makes HbA1c a moving average of glycemic control over the last 2–3 months, and is used as a recommended primary efficacy endpoint for clinical trials in diabetes mellitus type 27. This focus on routine and commonly available external and serum values is due in part to their convenience and accessibility. Historical studies regarding multisystem biomarkers in diabetes mellitus such as organ size, organ composition, fat composition, or sarcopenia are limited in their power due to practicality and cost. This information was studied in limited fashion using physical exam, ultrasound, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), or cadavers, with links suggested between the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 2 or glycemic control and multisystem changes from increased kidney size to changes in adipose tissue distribution8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. However, the scientific understanding of the overall multisystem effects of metabolic syndrome on the human body remains limited as these initiatives have been challenged by statistical power and, to date, prior work has been narrowly focused on individual systems or biomarkers.

Recent advancements in computer science and the technical capabilities of computational hardware have enabled and rapidly advanced the fields of deep learning and AI, unlocking the potential of algorithmic assistance in medical image segmentation and analysis16. These new capabilities supplement onerous and error-prone human effort with computational time and make possible routine extraction of biomarkers from medical imaging exams17,18. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) exams are an ideal candidate for this work, as they represent cross-sectional volumetric 3-dimensional images of the human body with consistent data values of X-ray attenuation/density in Hounsfield units (HU)18,19,20,21. The biomarkers that can be derived from CT exams have been shown to be understandable, explainable, and reproducible19. Several biomarkers obtainable from abdominopelvic CT exams have clear relevance to metabolic syndrome, including the size and density of visceral adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, liver, and kidneys. These have been studied in the setting of the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 219, but potential changes with varying glycemic control are not yet established.

This study compares imaging biomarkers extracted from CT exams with glycemic control as measured by HbA1c levels.

Results

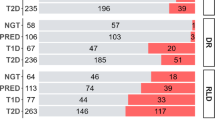

The final study cohort included 10,365 adult subjects with available HbA1c lab values (4932 females, 5433 males) within threshold from the date of their CT exam. The median time between the CT and HbA1c measurements was 3.5 months. The age distribution was nearly normal with mean(± SD) of 59.3 ± 14.4 years. Initially, the range from 45 to 75 was considered to approximate the middle standard deviation. However, to avoid confounding effects from coexisting conditions and age-related atrophy, the analyzed cohort age range was decreased by 5 years to an age range of 40–69 years inclusive. The sub-cohorts were female CT without contrast (n = 1984), female CT with contrast (n = 2948), male CT without contrast (n = 2595), and male CT with contrast (n = 2838). The female CT without contrast cohort will be primarily used for example purposes.

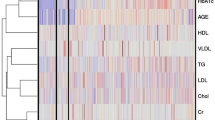

Seven biomarkers of statistical and physiologic interest, as well as the internal control of L1 trabecular density are shown in Table 1. The null hypothesis was accepted for L1 trabecular density, which lacked variance with Hb A1c across all sub-groups. The other biomarkers did show significant changes with glycemic control.

Visceral adipose tissue area increased with HbA1c (Fig. 1), a strongly significant relationship, with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients p < 0.001. The median VAT area between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts increased by 53% (156 cm2 vs. 239 cm2). Pairwise comparisons between groups with differing glycemic control using Dunn’s test revealed highly significant (p < 0.001) differences for all categories save between the diabetic and poorly-controlled groups, which were not significant. The pattern was a stepwise increase in VAT area with HbA1c until the diabetic range, then no further significant change from the diabetic to the poorly-controlled range. These findings were similar regardless of patient sex or the presence of intravenous contrast, with all subgroups shown in Fig. 1.

Distributions and statistical analysis of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) area at the L3 level between groups. For this and all similar figures, women are the top row and men the bottom; CT without IV contrast in the left column and CT with IV contrast in the right column. Box and whisker plots show the median, interquartile range, and the whiskers extend to the 5th and 95th percentile. All four subplots are shown on a consistent Y axis range. Statistically significant findings from the Kruskal-Wallis test are indicated with red font. Except as otherwise noted, all distributions are highly significantly different (p < 0.001). The pattern of significantly increasing VAT with increasing HbA1c to the diabetic category is consistent.

Kidney volume increased with HbA1c (Fig. 2), with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients p < 0.001. This was a monotonic increase with all subgroups highly significant for females with contrast-enhanced CT exams (p < 0.001 throughout), and while a similar pattern emerged for all other groups, not all pairwise tests were significant. The median kidney volume between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts increased by 22% (329 mL vs. 400 mL). Similarly, liver volume overall increased with HbA1c (Fig. 3), with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients p < 0.001. There were significant monotonic increases between all subgroups for females with contrast enhanced CT exams. For the other subgroups there was no significant difference between the non-diabetic and prediabetic groups with Dunn’s test, but a significant breakpoint was observed with increased liver volume between the pre-diabetic and diabetic HbA1c ranges. The median liver volume between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts increased by 24% (1650 mL vs. 2050 mL).

Distributions and statistical analysis of segmented kidney volume in cubic centimeters (= mL) between groups. Except as otherwise noted, all distributions are highly significantly different (p < 0.001). The overall pattern is increasing kidney volume with increasing HbA1c group. From a statistical standpoint this does not plateau above the diabetic range in all groups and continues to significantly increase in the CT exam groups with contrast. While there is a statistical plateau in the unenhanced CT groups, the median does continue to increase but the range broadens slightly.

Distributions and statistical analysis of segmented liver volume in cubic centimeters between groups. The pattern is increasing liver volume with increasing HbA1c. Except as otherwise noted, all distributions are highly significantly different (p < 0.001). In all groups there is a highly statistically significant difference between normal and prediabetic groups versus diabetic and poorly controlled diabetic levels of glycemic control. Only in women with contrast-enhanced CT exams was there also a significant increase in liver volume comparing normal to pre-diabetic groups. Only in men with contrast-enhanced CT exams was there a significant increase in liver volume from the diabetic to poorly- controlled diabetic range.

Liver density decreased with increasing HbA1c (Fig. 4), with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients p < 0.001. The statistically significant trend is decreased liver density with increasing HbA1c across sex and regardless of intravenous contrast, though not all pairwise Dunn’s subgroup tests individually achieved significance. The pattern is best observed in the contrast-enhanced female subgroup. The median liver density between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts decreased by 6% (52.7 HU vs. 49.5 HU).

Distributions and statistical analysis of the median segmented liver density in Hounsfield Units between groups. Except as otherwise noted, all distributions are highly significantly different (p < 0.001). The overall trend is decreasing density of the liver, which is likely due to increasing hepatic steatosis. This is statistically clearer on CT exams with intravenous contrast, owing in part to the decreased enhancement of steatotic livers.

Skeletal muscle area at the L3 vertebral body level increased with HbA1c (Fig. 5), with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients p < 0.001. However, not all individual subgroups were significant with Dunn’s test. For all groups, this effect appears to plateau at the diabetic level of glycemic control, with the muscle area in poorly controlled diabetes not statistically higher than in the diabetic group. The median skeletal muscle area between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts increased by 16% (134.4 cm2 vs. 156.4 cm2).

Distributions and statistical analysis of the muscle area in square centimeters at the representative slice from the L3 vertebral level between groups. Except as otherwise noted, all distributions are highly significantly different (p < 0.001). The overall trend is increasing muscle area, though not all individual subgroups are significant. In all groups this appears to plateau at the diabetic level of glycemic control, with the muscle area in poorly controlled diabetes not statistically higher than in the diabetic group.

Skeletal muscle density at the L3 vertebral body level decreased with increasing HbA1c (Fig. 6), with all Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests p < 0.003. All the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were highly significant (p < 0.001). While not all individual subgroups significantly differed by Dunn’s test, the trend was decreased muscular density with increasing HbA1c, reflecting increased myosteatosis. This was best observed in the female contrast-enhanced cohort. The median skeletal muscle density between the normal and poorly-controlled diabetic female non-contrast CT cohorts decreased by 21% (21.3 HU vs. 16.8 HU).

Discussion

With the exception of BMD, all other analyzed CT body composition biomarkers demonstrated statistically significant changes in at least one analyzed sub-cohort from normal to prediabetic Hb A1c ranges, as well as from the prediabetic to diabetic Hb A1c range. The L1 vertebral body trabecular density did not vary with glycemic control, accepting the null hypothesis (Table 1, also Supplementary Fig. 1), and effectively acting as a control variable. Thus, macroscopic physiologic changes of metabolic syndrome observable with CT biomarkers appear to begin in the pre-diabetic phase.

We observed a significant trend of increasing CT biomarkers for measures of body composition bulk or amount, including visceral adipose tissue (VAT) area, kidney volume, liver volume, and muscle area, with increasing HbA1c (Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 5). Across all groups, the biomarker changes were generally stepwise with increasing HbA1c from normal to pre-diabetic to the diabetic range. However, in at least one sub-cohort, of all seven biomarkers that statistically significantly varied with HbA1c, the biomarker did not significantly change further when comparing the diabetic and poorly controlled diabetic groups. This could be due to the physiologic changes plateauing, biomarker variability from more labile glycemic control in the poorly-controlled group, or perhaps some changes require additional time. As one example, chronic poorly-controlled diabetic patients with renal involvement frequently develop renal atrophy, which would increase the data variance in the higher HbA1c categories.

The pattern of significantly increasing VAT area with increasing HbA1c from the normal range to the diabetic category is consistent, and within expectations. However, in all groups, the VAT area plateaus in the diabetic category and does not significantly differ in patients in the poorly controlled category. The related biomarker ratio of VAT to SAT area related to glycemic control revealed sex-dependent changes in adipose tissue distribution, discussed in the Supplement. We observe a less strong but significant decrease in liver attenuation with increasing HbA1c, compatible with hepatic steatosis, also consistent with prior work22. The differences in liver density between groups were more accentuated after IV contrast as steatotic livers enhance less, in addition to starting at a lower HU level23. The ratio of VAT to SAT area related to glycemic control was sex dependent, explored further in the Supplement and illustrated on Supplementary Fig. 2.

We observe increased muscle area but decreased muscle density with increasing HbA1c, suggesting increased myosteatosis21. The best analogous prior study to this one compared hepatic steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and agrees with our findings, observing that intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) as approximated by paraspinal CT muscle density at L3 level decreased as liver disease worsened24. This is further supported by empiric work with pathologic confirmation showing impaired lipolysis in both adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in the setting of diabetes mellitus and obesity25, also in agreement with recently proposed physiologic mechanisms underlying insulin resistance and ectopic lipid accumulation26. However, the increased muscle area we observe differs from some prior works, predominately using DXA to measure skeletal muscle in various body regions, which reported decreased skeletal muscle with poor glycemic control as an indicator for high cardiometabolic risk27,28. The divergence observed could be due to differences in technique, with partial volume averaging of increased IMAT decreasing the density seen by DXA, or differences in normalization.

We observe increased renal size with increasing HbA1c. This is concordant with complimentary literature, with the mechanism believed to be compensatory increased glomerular filtration as the kidneys excrete glucose. Eventually this compensatory effect fails, leading patients with chronic poor glycemic control to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and renal atrophy. These atrophic changes may underlie the larger observed renal volume variance in the poorly controlled cohort.

The indications and thus populations of patients receiving contrast-enhanced CT exams versus unenhanced CT exams likely differ somewhat. To some degree, patients with unenhanced CT exams are more likely to have contrast deferred due to chronic kidney disease, which is associated with longstanding diabetes mellitus and poor glycemic control. We suspect this may account for the widened distribution of kidney volumes seen in the unenhanced CT groups for both women and men in the poorly controlled category shown in Fig. 2.

Additional limitations of this retrospective study include expected enrichment in patients with or with suspected metabolic syndrome. Although results for the Kruskal-Wallis and Spearman’s rests were generally highly statistically significant, the effect sizes were generally small or medium, limiting the interpretation in individual subjects. Due to retrospective analysis, our cohort is predicated on HbA1c laboratory orders from routine clinical practice. This allows norms to be established for different ranges of glycemic control, but we recognize this does not reflect the general population and may limit generalizability. Another limitation is related to the timing of the HbA1c measurement relative to the analyzed CT exam, which was a median of 3.5 months. This is reasonable for most patients, but in the setting of labile or poor glycemic control a tighter relationship between CT scan time and HbA1c may be beneficial. These limitations could be addressed in the future with prospective or multi-center studies. Additionally, all exams in this cohort are from unique patients. While this was a deliberate choice, future work analyzing pairwise changes in biomarkers from the same patients at different times with differing levels of glycemic control would be illustrative to confirm these relationships and explore if they are reversible. The present work also does not attempt to account for the length of time since diabetic diagnosis, historic glycemic control, or treatment.

The use of HbA1c as our serum biomarker introduces limitations due to lab variability or false elevation in certain settings such as iron-deficiency or sickle-cell anemia, renal or liver failure, sickle-cell anemia, or recent transfusion. As shown in Fig. 7, the glycemic control distribution in our cohort is non-parametric. This is to be expected, with the skewed peak in the well-managed range. However, the tail extends sufficiently into the higher HbA1c range for statistically useful comparison groups.

Histogram of the nearest Hb A1c value to CT scan in our cohort of over 10,000 adults, color coded by the four categories named “Normal” (n = 1984), “Pre-Diabetes” (n = 2948), “Diabetes” (n = 2595), and “Poorly Controlled” (n = 2838). The distribution has an expected peak near the upper limit of normal and pre-diabetic range, reflecting the pre-test probability for ordering Hb A1c in routine practice.

In summary, this work represents the largest cohort analysis to date demonstrating the multisystemic physiologic effects of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome at differing levels of glycemic control. Through a suite of quantitative imaging body composition biomarkers extracted from CT exams, we show the effects of metabolic syndrome largely begin in pre-diabetes and continue into the diabetic range as measured by HbA1c. We confirm several imaging trends with high statistical power and further support the importance of inter- and intra-muscular adipose tissue as a biomarker in metabolic syndrome, which CT is ideal to measure. This and future related work offer the potential to augment and improve the definition and measurement of metabolic syndrome. All of these imaging biomarkers may be repurposed opportunistically from abdominal CT scans performed for any indication, adding value through understanding the physiologic effects of metabolic syndrome and glycemic control, potentially predicting which patients scanned for other reasons would benefit from biochemical evaluation and endocrinology referral, and providing insights into the physiology of new therapies such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists and sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors29,30.

Methods

This consecutive patient series represents a retrospective study which was HIPAA-compliant, approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was waived for this minimal risk retrospective study. Inclusion criteria required adults aged 18 or older with an available abdominal CT exam (without or with intravenous contrast in the portal venous phase) and a HbA1c lab draw within 2 years of the CT exam. Patients were divided into four categories of glycemic control according to the closest HbA1c measurement to the time of their CT exam, defined as: normal: <5.7%; pre-diabetes: 5.7–6.4%; diabetes: 6.5–8.9%; and poorly controlled diabetes: ≥9.0%. For patients where more than one CT was available meeting these criteria, the earliest was included; every CT exam thus represents a unique patient. The proportion of our dataset in each glycemic category is illustrated in Fig. 7. Women and men were analyzed separately, and within these groups unenhanced and contrast-enhanced CT scans were also separately analyzed.

Abdominal CT biomarkers were extracted from these exams using a validated pipeline of fully-automated algorithms using methodology previously described20,21. Patient examples of the CT segmentations for each glycemic control group are illustrated in Fig. 8. The individual CT biomarker tools were previously developed and validated on separate cohorts, with subsequent improvements in algorithm performance and efficiency (see supplementary methods). Biomarkers from a standardized 2D slice at the L3 vertebral level were utilized for visceral adipose tissue (VAT) area, superficial adipose tissue (SAT) area, skeletal muscle (SM) area, and SM density (in HU). The L1 vertebral body was utilized for trabecular bone mineral density (BMD). Volumetric biomarkers included 3D segmentations of the liver and kidneys, which allowed calculation of the organ volumes and median density (in HU).

Representative images illustrating the AI algorithm segmentation and body composition extraction from routine CT exams. For this figure, contrast-enhanced CTs of female patients from each HbA1c category were selected (rows) and segmented axial images with color overlay from the L1 level (left column), L3 level (middle column), and maximum intensity projection (MIP) images in coronal projection (right column) are shown. Color code: Blue is superficial fat, yellow is visceral fat, red is skeletal muscle, brown is liver, orange is spleen, and green is vertebral trabecular region. Progressive changes related to visceral fat and liver volume are most visually apparent from this composite figure.

All CT biomarker measurements were adjusted for age to the mean cohort age of 55 years. The adjusted biomarker results for each HbA1c group were then compared using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test with post-test pairwise comparisons performed with Dunn’s test. Multiple comparisons were accounted for using the Holm-Šidák stepwise adjustment with an overall significance level of a‘ = 0.0531. Overall trends of individual HbA1c levels with adjusted biomarker results were assessed using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Access to limited or deidentified data sets may be obtained after receipt of institutional review board approval and enactment of Data Use Agreements to ensure protection of patient data. Please direct requests to the corresponding author.

References

Hirode, G. & Wong, R. J. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA. 323, 2526–2528. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4501 (2020).

Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P., Shaw, J. & Group, I. D. F. E. T. F. C. The metabolic syndrome—A new worldwide definition. Lancet. 366, 1059–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8 (2005).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 112, 2735–2752. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 (2005).

Expert Panel on Detection. Treatment of high blood cholesterol in, A. Executive Summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 285, 2486–2497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.19.2486 (2001).

Alberti, K. G. & Zimmet, P. Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med.15, 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::aid-dia668>E3.0.co;2-s (1998).

Pickhardt, P. J. Metabolic syndrome: the urgent need for an imaging-based definition. Radiographics. 44, e230230. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.230230 (2024).

King, P., Peacock, I. & Donnelly, R. The UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS): clinical and therapeutic implications for type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.48, 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00092.x (1999).

HEPATOMEGALY and diabetes. J. Am. Med. Assoc.154, 342. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1954.02940380052016 (1954).

Wiseman, M. J., Saunders, A. J., Keen, H. & Viberti, G. Effect of blood glucose control on increased glomerular filtration rate and kidney size in insulin-dependent diabetes. N Engl. J. Med.312, 617–621. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198503073121004 (1985).

Sakkas, G. K. et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on muscle size and strength in patients receiving dialysis therapy. Am. J. Kidney Dis.47, 862–869. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.01.013 (2006).

Park, S. W. et al. Excessive loss of skeletal muscle mass in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 32, 1993–1997. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-0264 (2009).

Molina, D. K. & DiMaio, V. J. Normal organ weights in men: part II-the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol.33, 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad (2012).

Kalyani, R. R., Tra, Y., Egan, J. M., Ferrucci, L. & Brancati, F. Hyperglycemia is associated with relatively lower lean body mass in older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 18, 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0445-0 (2014).

Misra, A. et al. Body fat patterning, hepatic fat and pancreatic volume of non-obese Asian indians with type 2 diabetes in North India: a case–control study. PLoS ONE. 10, e0140447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140447 (2015).

Hancu, A. & Radulian, G. Changes in fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c and triglycerides are related to changes in body composition in patients with type 2 diabetes. Maedica (Bucur). 11, 32–37 (2016).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM. 60, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386 (2017).

Pyrros, A. et al. Opportunistic detection of type 2 diabetes using deep learning from frontal chest radiographs. Nat. Commun.14, 4039. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39631-x (2023).

Pickhardt, P. J., Jee, Y., O’Connor, S. D. & del Rio, A. M. Visceral adiposity and hepatic steatosis at abdominal CT: Association with the metabolic syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.198, 1100–1107. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.11.7361 (2012).

Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Utilizing fully automated abdominal CT-based biomarkers for opportunistic screening for metabolic syndrome in adults without symptoms. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.216, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.20.23049 (2021).

Tallam, H. et al. Fully automated abdominal CT biomarkers for type 2 diabetes using deep learning. Radiology. 304, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.211914 (2022).

Nachit, M., Horsmans, Y., Summers, R. M., Leclercq, I. A. & Pickhardt, P. J. AI-based CT body composition identifies myosteatosis as key mortality predictor in asymptomatic adults. Radiology. 307, e222008. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.222008 (2023).

Yu, R., Shi, Q., Liu, L. & Chen, L. Relationship of Sarcopenia with steatohepatitis and advanced liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol.18, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0776-0 (2018).

Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Detection of moderate hepatic steatosis on portal venous phase contrast-enhanced CT: evaluation using an automated artificial intelligence tool. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.221, 748–758. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.23.29651 (2023).

Kitajima, Y. et al. Severity of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with substitution of adipose tissue in skeletal muscle. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.28, 1507–1514. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12227 (2013).

Jocken, J. W. et al. Insulin-mediated suppression of lipolysis in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic men and men with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetologia. 56, 2255–2265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2995-9 (2013).

Petersen, M. C. & Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev.98, 2133–2223. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00063.2017 (2018).

Chen, L. Y. et al. Skeletal muscle loss is associated with diabetes in middle-aged and older Chinese men without non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Diabetes12, 2119–2129. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i12.2119 (2021).

Hong, S. et al. Relative muscle mass and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 12, e0188650. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188650 (2017).

Nakatani, S. et al. Dapagliflozin administration for 1 year promoted kidney enlargement in patient with ADPKD. CEN Case Rep.https://doi.org/10.1007/s13730-023-00840-4 (2023).

Sinha, F. et al. Empagliflozin increases kidney weight due to increased cell size in the proximal tubule S3 segment and the collecting duct. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1118358. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1118358 (2023).

Dinno, A. Nonparametric pairwise multiple comparisons in independent groups using Dunn’s test. Stata J. Promot Commun. Stat. Stata. 15, 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1501500117 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.W. and P.J.P. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.J.P.: advisor to Bracco Diagnostics, GE HealthCare, Nanox-AI, and ColoWatch; J.W.G.: Advisor to RadUnity, Shareholder in NVIDIA; R.M.S.: Royalties from iCAD, ScanMed, Philips, Translation Holdings, PingAn, MGB; research support through a CRADA with PingAn. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Warner, J.D., Blake, G.M., Garrett, J.W. et al. Correlation of HbA1c levels with CT-based body composition biomarkers in diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep 14, 21875 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72702-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72702-7

This article is cited by

-

Methodology for a fully automated pipeline of AI-based body composition tools for abdominal CT

Abdominal Radiology (2025)