Abstract

Presently, multi-label classification algorithms are mainly based on positive and negative logical labels, which have achieved good results. However, logical labeling inevitably leads to the label misclassification problem. In addition, missing labels are common in multi-label datasets. Recovering missing labels and constructing soft labels that reflect the mapping relationship between instances and labels is a difficult task. Most existing algorithms can only solve one of these problems. Based on this, this paper proposes a soft-label recover based label-specific features learning (SLR-LSF) to solve the above problems simultaneously. Firstly, the information entropy is used to calculate the confidence matrix between labels, and the membership degree of soft labels is obtained by combining the label density information. Secondly, the membership degree and confidence matrix are combined to construct soft labels, and this process not only solves the problem of missing labels but also obtains soft labels with richer semantic information. Finally, in the process of learning specific label features for soft labels. The local smoothness of the labels learned through stream regularization is complemented by the global label correlation, thus improving the classification performance of the algorithm. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, we conduct comprehensive experiments on several datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main task of multi-label learning (MLL) is to learn an effective classification model that assigns an appropriate set of labels to unknown instances. MLL has been widely used in many fields, such as automatic image annotation1, text classification2, protein function prediction3, personalized recommendation4, etc. In MLL, it is not reasonable that label predictions are determined by the same features. For example, in an image recognition task, markers such as “blue sky” and “white cloud” are closely related to color features, while local texture features are not sensitive. These kinds of features that are related to the label to a large extent and have strong discriminative ability are called label-specific features (LSF).

However, most of the existing multi-label datasets are obtained by manual annotation or web crawler. As the volume of data increases, manual annotation becomes increasingly costly. In contrast, web crawlers tend to crawl unknown data, which makes it increasingly difficult to obtain instances with complete labels and relatively easy to obtain instances with incomplete label information. Incomplete label information severely diminishes the performance of MLL algorithms, so missing MLL is of great research value.

Label correlation5 (LC) is an important a priori information. It can effectively improve the performance of missing MLL. However, most existing MLL utilizes cosine similarity to compute LC to recover missing label. Cosine similarity is more dependent on the completeness of the labels. Reliability of MLL algorithms can be improved by using it on the complete dataset. But when labels are missing, the LC calculated by cosine similarity is often mixed with spurious correlation, making it difficult to effectively recover. Thus, the known features and labels in the training data are combined to learn the global and local relevance of the labels and in this way improve the reliability of the labels.

Most of the LSF algorithms are implemented based on logical labels. The either-positive-or-negative label pattern inevitably degrades the accuracy of multi-label classification. Soft label provides a more accurate description of the relationship to which the label belongs than logical labels. Inspired by the label enhancement proposed by Xu et al.6, logical label is subject to artificial division thresholds, which leads to label misclassification problems thus reducing label reliability. Soft label avoids the above problems and effectively improve the reliability of the label space. In single-positive multi-label learning7, both feature selection8 and deep learning9 can improve the performance of the corresponding algorithms.

In Fig. 1, (a) shows the soft labels, while (b), (c), and (d) show the logical labels obtained at different thresholds, where each color represents a class of labels. As shown in (b), the missing labels diminish the label reliability of the label more than the one that appears in (c). Compared with (c), the known labels in (d) are far more than the unknown labels. From Fig. 1, we can observe that it is impossible to classify multiple labels to provide the basis for the construction of soft labels. It is clear to see that soft-labels in (a) can describe the mapping relationship between labels and instances much better than the logical labels in (c). We observe that the confidence matrix makes full use of known label and label density information in the label space. It transforms logical labels into soft labels that describe the mapping relationship between labels and instances, and reduces the impact of artificial division thresholds on multi-label datasets.

Based on the above analysis: this paper proposes a soft label recover based class attribute learning algorithm (SLR-LSF). The main contributions include:

-

(1)

Inspired by the fact that soft labels are more consistent with the nature of the data than logical labels, we used the combination of the confidence matrix and the original label information to construct the soft label and recover the missing labels.

-

(2)

Under the conditions of the process of learning LSF of soft labels, we propose to use the local smoothness of the labels obtained by manifold regularization to complement the global correlation, and therefore improve the performance and robustness of the SLR-LSF algorithm.

-

(3)

The effectiveness of algorithm in this paper is verified by comparing it with several advanced MLL algorithms on multiple datasets at different missing rates.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In “Related work” section, we introduce the process of constructing multi-label models and soft labels. In “Construction and optimization of SLR-LSF model” section, we present the construction and optimization of the SLR-LSF model. The datasets, evaluation metrics, parameter settings of different algorithms and experimental results on full and label-missing datasets are presented in “Evaluation and discussion” section. In “Analysis of the algorithm” section, we validate the proposed method with ablation analysis, parametric sensitivity analysis and statistical hypothesis testing. Finally, we conclude our work in “Conclusion” section.

Related work

Zhang et al. were the first who proposed LSF algorithm LIFT10. In this algorithm, K-means was used to classify the labels into positive and negative classes based on LSF of the labels, and then the SVM classifier was used to classify the labels. However, this algorithm did not consider the correlation between labels. The LLSF-DL11 algorithm proposed by Huang et al. used cosine similarity to calculate the pairwise relationship between labels in the process of LSF learning to classify multi-label. However, this algorithm is incomplete in terms of considering the LC. The MLFC12 algorithm proposed by Zhang et al. considered that similar samples have similar features in similar labels. In this work, to effectively improve the performance of multi-label classification algorithms, similar samples have jointly learned LC and LSF. Regarding this problem, Wang et al.13 have made great improvements to multi-label classification algorithms by mitigating the effect of artificial division thresholds through density labels instead of logical labels. The LSR-LSF14 algorithm proposed by Cheng et al. used a label propagation method to reshape original label space. In this algorithm, the logical labels are converted into digital labels and LSF are extracted for the digital label matrix. However, the numerical matrix extracted by this algorithm has negative probability values for some of the labels, so the relevant information of the labels is inevitably lost. Based on a combination of distributed learning and multi-label LSF learning, Li et al.15 have proposed mapped features to a high-dimensional space. In this algorithm, the non-linear relationship between labels and features is explored to enhance the original labels, and then the LSF of the enhanced labels are learned. Nevertheless, the algorithm does not take the noisy and redundant data in high-dimensional feature space into account, which affects the accuracy of multi-label classification.

Currently, there are three main methods to solve the missing label problem: (1) Ignoring missing labels. In this method, a loss function is constructed on the known labels. The representative one of this method is the ERM16 framework proposed by Yu et al. (2) Treating missing labels as negative labels. However, this method suffers from losing some semantic information. The representative one of this method is the WELL17 algorithm proposed by Sun et al. (3) Recovering missing labels using the latent semantic structure of known labels. This approach adopted LC to recover values of missing labels. Representative ones of this method include the LSML18 algorithm proposed by Huang et al. which recovered missing labels by learning higher-order LC matrices and LSF. This algorithm does not take into account the local correlation of the labels. The GLOCAL19 algorithm proposed by Zhu et al. succeeded to recover the missing labels by learning local and global LC in low-rank space. But this algorithm does not fully utilize the instance correlation. Wang et al. proposed the LE-TLLR20 algorithm that uses a two-level label recovery mechanism to recover the missing labels considering both label and instance correlation. However, this algorithm does not make full use of local correlation. Cheng et al. in GLMAM21 proposed to recover missing labels by combining global and local correlation of instances and labels through an attention mechanism. A low-rank method can also be used to recover missing labels, such as ML-LEML22 algorithm. This algorithm used low-rank structure and instance-level semantic correlation matrix to recover missing labels based on the hypothesis that label sets of the same topic are highly concentrated and label sets of different topics are independent of each other. Nevertheless, in this algorithm, LC is not fully utilized. Ma et al. proposed DM2L-l23 algorithm to recover missing labels by considering the combination of the local and global nature of labels and low-rank structure. Kumar et al. proposed LRMML24 algorithm to recover by low-rank label subspace transformation and global and local LC learning.

Construction and optimization of SLR-LSF model

Multi label model

In MLL, the feature matrix \(\:\varvec{X}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{n\times\:d}\), and the label matrix \(\:\varvec{Y}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{n\times\:\ell}\), where \(\:\ell\) is the number of labels, \(\:n\) is the number of instances, and \(\:d\) is the number of features. The multi-label data set is denoted as \(\:\varvec{D}=\left\{\left({\varvec{x}}_{\varvec{i}},{\varvec{y}}_{\varvec{i}}\right)|1\le\:i\le\:n\right\}\), where \(\:{\varvec{x}}_{i}=\left\{{x}_{i1},{x}_{i2},\dots\:,{x}_{id}\right\}\) represents the feature vector and \(\:{\varvec{y}}_{i}=\left\{{y}_{i1},{y}_{i2},\dots\:,{y}_{i\ell}\right\}\) represents the label vector. The purpose of MLL is to find a mapping relation \(\:f:\varvec{X}\to\:{2}^{\varvec{Y}}\).

Construction of soft labels

In information theory, entropy is an important tool for measuring uncertainty25. Given the sets \(\:A=\left\{{a}_{1},{a}_{2},\dots\:,{a}_{m}\right\}\), \(\:B=\left\{{b}_{1},{b}_{2},\dots\:,n\right\}\), \(\:P\left(a\right)\) and \(\:P\left(b\right)\) are the prior probabilities of the elements in the sets \(\:A\) and \(\:B\) respectively. Then the entropy of the set \(\:A\) is:

The larger \(\:H\left(A\right)\) is, the greater is the uncertainty of the set \(\:A\). Moreover, the conditional entropy of set \(\:B\) in the case of a known set \(\:A\) is:

\(\:H\left({b}_{j}|{a}_{i}\right)\) is the degree of uncertainty of element \(\:{b}_{i}\) when element \(\:{a}_{i}\) is known. If \(\:H\left({b}_{j}|{a}_{i}\right)\) is larger, the uncertainty between the two elements is larger, and vice versa, there is a correlation between the two elements. Denoted as:

where \(\:P\left({a}_{i}{b}_{j}\right)\) is the joint probability of elements \(\:{a}_{i}\) and \(\:{b}_{j}\) and \(\:P\left({b}_{j}|{a}_{i}\right)\) is the conditional probability.

Ambiguity is a characteristic of data. Instead of belonging to only one instance, any label belongs to all instances with a certain probability. Therefore, the real labels are not deterministic logical labels, but soft labels that can reflect the mapping relationship between labels and instances. As the amount of data increases, missing labels will inevitably appear. In this paper, we define + 1 denotes a known label, -1 denotes an unknown label, and 0 denotes an uncertain label. The confidence matrix26,27 and the label density information are combined to calculate the membership degree of the soft labels. The soft labels are constructed by combining the membership degree and the logical labels. The formulas that use to calculate this combination can be expressed as follows:

where \(\:{\ell}_{j}^{-},{\ell}_{i}^{+},{\ell}_{j}^{0},{\ell}_{j}^{+},{\ell}_{i}^{-},{\ell}_{i}^{0}\:\left(i=\text{1,2},.,\ell, j=\text{1,2},.,\ell, i\ne\:j\right)\) represent negative label, positive label, missing label respectively. \(\:{\varvec{a}}_{ij}\) and \(\:{\varvec{b}}_{ij}\) represent the effect of positive labels on negative labels and missing labels. \(\:{\varvec{c}}_{ij}\) and \(\:{\varvec{d}}_{ij}\) represent the effect of negative labels on positive labels and missing labels. \(\:{\varvec{e}}_{ij}\) and \(\:{\varvec{f}}_{ij}\) refer to the effect of missing labels on positive labels and negative labels. To minimize the dependence on the nonequilibrium parameter, we respectively calculate the density values of positive labels, 0 labels and negative labels in the original space as \(\:\varvec{Y}{\varvec{P}}_{+}\), \(\:{\varvec{Y}\varvec{P}}_{0}\), and \(\:\varvec{Y}{\varvec{P}}_{-}\). Due to the number of original labels of a certain type being zero, we propose to use one extra-base label for each category as a default to avoid the construction of soft labels.

Our dataset was downloaded from the official website and is the complete multi-label public dataset by default. The missing dataset is generated using a random missing function to obtain a random missing matrix, simulating the missing dataset based on the labels from the complete dataset in the form of the Hadamard product. In the missing dataset, + 1 denotes a known label, −1 denotes an unknown label, and 0 denotes an uncertain label. In multi-label datasets, known labels are much fewer than unknown labels, so here we should focus on exploring the semantic information implied by unknown labels.

Furthermore, in the known multi-label dataset, + 1 labels are much more numerous than − 1 labels. To increase the weight of + 1 labels, we multiply the confidence matrix of known positive labels by the probability of −1 labels existing in the labels, obtaining \(\:-\left({\varvec{a}}_{ij}+{\varvec{b}}_{ij}\right) \odot \varvec{Y}{\varvec{P}}_{-}\) and similarly obtaining \(\:+\left({\varvec{c}}_{ij}+{\varvec{d}}_{ij}\right) \odot \varvec{Y}{\varvec{P}}_{+}\).The confidence matrix \(\:\left({\varvec{e}}_{ij}+{\varvec{f}}_{ij}\right)\) represents uncertain information, so when constructing soft labels, we should also reduce the influence of uncertain labels on the soft label matrix, that is, decrease the weight of uncertain labels. Thus, we obtain \(\:-\left({\varvec{e}}_{ij}+{\varvec{f}}_{ij}\right) \odot \varvec{Y}{\varvec{P}}_{0}\). Therefore, Eq. (7) can be written as:

where \(\:\varvec{Y}\) is the logical label matrix and \(\odot\) denotes the Hadamard product.

Construction of the model

Based on the Combination of Eq. (1), Eq. (7), and the LLSF28, the SLR-LSF algorithm base model will be as follows:

where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\:\)is the regularization parameter, \(\:\varvec{W}=\left[{\varvec{w}}_{1},{\mathbf{w}}_{2},{\mathbf{w}}_{3},\dots\:,{\mathbf{w}}_{\ell}\right]\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{d\times\:\ell}\) is the weight coefficient, \(\:{\mathbf{w}}_{\ell}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{d\times\:1}\) represents the specific features of each label.

The model in this paper uses the \(\:{l}_{1}\)-norm to constrain \(\:\varvec{W}\) which enables feature sparsity. The parameter \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\) can shrink some of the values of \(\:\varvec{W}\) to zero to extract LSF. Assuming that samples with similar labels are similar in features, the corresponding class labels \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:{y}_{j}\) are similar, and their corresponding LSF \(\:{\varvec{w}}_{i}\) and \(\:{\varvec{w}}_{j}\) are similar too. Based on the Euclidean distance used to measure the similarity between \(\:{\varvec{w}}_{i}\) and \(\:{\varvec{w}}_{j}\), Eq. (8) can be rewritten as follows:

where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) is the regularization parameter of the global correlation, \(\:\varvec{C}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{\ell\times\:\ell}\) denotes the global correlation matrix of the labels. Since \(\:\varvec{C}\) is an asymmetric matrix, we make \(\:\varvec{C}=\frac{\varvec{C}+{\varvec{C}}^{\mathbf{T}}}{2}\) to make the matrix \(\:\varvec{C}\) symmetric in order to avoid the undesirable effect of Eq. (9) on Eq. (8).

In the SLR-LSF model, labels not only include global correlations, but also local smoothing. In this model, we use manifold regularization to learn the local smoothness, and global correlation of the labels to enhance the robustness of our algorithm. The SLR-LSF model proposed in this paper is shown below:

where \(\:\varvec{L}\) is the Laplacian matrix, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\) is the regularization parameter for local smoothness and the manifold regularization preserves the manifold structure of instance similarity and LC.

Optimization of SLR-LSF model

The SLR-LSF model is a convex optimization problem with two variable matrices, the weight matrix \(\:\varvec{W}\) and the LC matrix \(\:\varvec{C}\). Due to the non-smoothness of the \(\:{l}_{1}\)-norm, we adopt the alternating iterations addressed in the accelerated proximal gradient descent method29 to solve the optimal problem of non-smoothness of the objective function.

The objective function is:

where \(\:\mathcal{H}\) is the Hilbert space. \(\:f\left(\varvec{W}\right)\) and \(\:g\left(\varvec{W}\right)\) are both convex functions and satisfy the Lipschitz condition. The expressions are shown in Eq. (12) and Eq. (13).

For any matrix\(\:{\varvec{W}}_{1}\), \(\:{\varvec{W}}_{2}\)

where \(\:{L}_{g}\) is the Lipschitz constant. \(\:\varDelta\:\varvec{W}={\varvec{W}}_{1}-{\varvec{W}}_{2}\). Introducing \(\:\varvec{Q}\left(\varvec{W},{\varvec{W}}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\) as a quadratic approximation to \(\:F\left(\varvec{W}\right)\), then \(\:\varvec{Q}\left(\varvec{W},{\varvec{W}}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\):

Let \(\:{\varvec{q}}_{t}\left(\varvec{W}\right)={\varvec{W}}_{t}-\frac{1}{{L}_{g}}\nabla\:f\left(\varvec{W}\right)\), then

According to the study given in the literature30:

In Eq. (18), \(\:{\theta\:}_{t}\) satisfies \(\:{\theta\:}_{t+1}^{2}-{\theta\:}_{t+1}\le\:{\theta\:}_{t}^{2}\), while the convergence rate of \(\:\varvec{O}\left({t}^{-2}\right)\) is improved. \(\:{\varvec{W}}_{t}\) is the result of the \(\:\varvec{t}\)th iteration of \(\:\varvec{W}\). The soft threshold function for performing iterative operations is shown in Eq. (19):

where \(\:{\varvec{S}}_{\epsilon\:}\left[\cdot\:\right]\) is the soft threshold operator. For any one parameter \(\:{w}_{ij}\) and \(\:\epsilon\:\), then:

The Lipschitz constant can be calculated as follows:

Therefore, the Lipschitz constant of the SLR-LSF model is:

Next, optimizing LC matrix \(\:\varvec{C}\). The objective function is:

The LC matrix \(\:\varvec{C}\) is obtained as

Finally, we propose a linear model to derive the forecast label vector \(\:{\varvec{\delta\:}}_{t}\), \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{t}={\varvec{X}}_{t}\varvec{W}\):

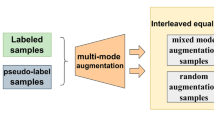

The framework of SLR-LSF algorithm is shown below:

Evaluation and discussion

Data sets

To validate the efficacy of the proposed algorithm in this paper, we utilized 12 publicly available multi-label datasets spanning diverse domains. One notable dataset is the Birds dataset, initially employed in the MLSP competition for concurrent acoustic classification of multiple bird species amidst noisy conditions. Another dataset, Medical, comprises text-based records originally intended for clinical medical diagnoses. Additionally, the Genbase dataset delineates various proteins alongside their structural categories. Detailed descriptions of these datasets are provided in Table 1.

Evaluation metrics

We select five metrics in MLL algorithms to measure the advantages of the SLR-LSF algorithm, namely Hamming Loss (HL), Average Precision (AP), One-error (OE), Ranking Loss (RL), and Coverage (CV). A larger value for AP metrics indicates better algorithm performance, while smaller values for the other metrics indicate better. Each indicator is defined below:

-

(1)

HL: HL is a metric used to examine how many times a sample is mis-classified in a single label. The formula of HL is:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{HL}_{D}\left(f\right)=\frac{1}{n}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}\frac{{Y}_{i}\varDelta\:{Z}_{i}}{M}\end{array}$$(26)where \(\:M\) is the total number of labels, \(\:{Y}_{i}\) is the set of true labels of sample \(\:i\), \(\:{Z}_{i}\) is the set of predicted labels of sample \(\:i\), \(\:\varDelta\:\) is the symmetric difference between the two sets and \(\:{rank}_{f}\) is the ranking function.

-

(2)

AP: AP is the average fraction of evaluated labels \(\:y\in\:{Y}_{i}\) and correctly sorted. The formula of AP is:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{AP}_{D}\left(f\right)=\frac{1}{n}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}\frac{1}{\left|{Y}_{i}\right|}\times\:\sum\:_{y\in\:{Y}_{i}}\frac{\left|\left\{y|{rank}_{f}\left({x}_{i},y\right)\le\:{rank}_{f}\left({x}_{i},y\right)y\in\:{Y}_{i}\right\}\right|}{{rank}_{f}\left({x}_{i},y\right)}\end{array}$$(27) -

(3)

OE: OE indicates the number of incorrect sorting in the instances category marker sort. The formula of OE is:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{OE}_{D}\left(f\right)=\frac{1}{n}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}g\left[\left[arg\underset{y\in\:Y}{{max}}f\left({x}_{i},y\right)\right]\notin\:{Y}_{i}\right],\:g\left(x\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\:0\:\:\:\:x\:is\:false\\\:\:1\:\:\:\:x\:is\:\:\:true\end{array}\right.\end{array}$$(28) -

(4)

RL: RL can represent the case where the category label of a sample is incorrectly ordered ahead of the correct label. The formula of RL is:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{RL}_{D}\left(f\right)=\frac{1}{n}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}\frac{1}{\left|{Y}_{i}\right|\left|\stackrel{-}{{Y}_{\ell}}\right|}\times\:\left|\left\{\left({y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)|f\left({x}_{i},{y}_{1}\right)\le\:f\left({x}_{i},{y}_{2}\right),\left({y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\in\:{Y}_{i}\times\:\stackrel{-}{{Y}_{\ell}}\right\}\right|\end{array}$$(29) -

(5)

CV: CV can examine how well the desired label covers all the labels in the category label ranking of the instances. The formula of CV is:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{CV}_{D}\left(f\right)=\frac{1}{n}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}\underset{y\in\:{Y}_{i}}{{max}}{rank}_{f}\left({x}_{i},y\right)-1\end{array}$$(30)

Comparison algorithm and parameter settings on the complete label

To verify the performance of our proposed algorithm, we select five multi-label classification algorithms to compare with the SLR-LSF algorithm:

-

(1)

The GroPLE31 algorithm is a multi-labeling algorithm for LSF by embedding feature and label groups into a low-dimensional space with parameters set to \(\:\alpha\:,\:\beta\:\in\:\left[{10}^{-4}{,10}^{4}\right]\), \(\:\gamma\:\in\:\left[{10}^{-2}{,10}^{2}\right]\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\in\:\left[{10}^{-3}{,10}^{2}\right]\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\in\:\left[{10}^{-3}{,10}^{2}\right]\).

-

(2)

The GLSFL-LDCM13 algorithm expands the classification margin by label density information and uses spectral clustering to extract the group-label-specific features of each label. The parameters are set as follows: the number of clusters \(\:K\)=\(\:\left[1:1:10\right]\), \(\:\epsilon\:=0.01\), \(\:\alpha\:=1\), \(\:\mu\:\in\:\left\{0.1,1,10\right\}\), penalty factor \(\:C\) and RBF kernel parameter \(\:\gamma\:\in\:\left\{1,\text{10,100}\right\}\).

-

(3)

The LLSF28 algorithm improves the classification performance by learning the cosine similarity between the labels with parameters set to \(\:\alpha\:={2}^{-4}\), \(\:\beta\:={2}^{-6}\), \(\:\gamma\:=1\).

-

(4)

The LSI-CI32 algorithm improves the classification performance of label-specific feature learning by learning inter-feature and inter-label correlation information separately. Where parameters are set as follows: \(\:\alpha\:={2}^{10}\), \(\:\beta\:={2}^{8}\), \(\:\gamma\:=1\), \(\:\theta\:={2}^{-8}\).

-

(5)

The LSR-LSF14 algorithm improves the classification performance of LSF by learning the numerical labels after label propagation. The parameters are set as follows: \(\:\alpha\:\in\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{6}\right]\), \(\:\beta\:\in\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{4}\right]\), \(\:\gamma\:\in\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{10}\right]\), \(\:\theta\:\in\:\left\{0.1,1,10\right\}\).

-

(6)

The SLR-LSF algorithm converts the logical labels into soft labels by using the confidence matrix and the density information of the original labels and recovering the missing labels at the same time. Finally learning LSF for soft labels. The parameters are set to \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1},{\lambda\:}_{2},{\lambda\:}_{3}\in\:\left[{10}^{-10},{10}^{10}\right]\).

-

(7)

SLR-LSF-SVM are extensions of the SLR-LSF algorithm that input the learned \(\:\varvec{W}\) into two classifiers. The parameter settings are both the same as SLR-LSF.

The experimental results of our algorithm and five advanced comparison algorithms on the complete data set are shown in Table 2. The five tables correspond to HL, AP, OE, RL, and CV metrics, respectively. Experimental results are given in the form of the \(\:\left(\text{m}\text{e}\text{a}\text{n}\pm\:\text{s}\text{t}\text{d}\right)\), “↑” (“↓”) represents the larger or smaller the metrics is the better. The superior experimental results in each data set are bolded and enlarged. From the Table 2, we can draw the following conclusions.

-

(1)

SLR-LSF is much better than LLSF and LSR-LSF algorithms. This indicates that more LSF can be extracted for soft labels. And, LSR-LSF algorithm loses critical semantic information when converting logical labels to numerical labels, leading to lower learned class discriminative attributes than LSR-LSF.

-

(2)

SLR-LSF algorithm significantly outperforms 5 comparison algorithms in the HL, AP, RL, and CV metrics. In terms of the OE metric, SLR-LSF algorithm doesn’t have more advantages than GLSFL-LDCM on 12 datasets, but the number of datasets where SLR-LSF-SVM is superior is the same as that of GLSFL-LDCM. From the perspective of average ranking, SLR-LSF is significantly better than SLR-LSF-SVM and GLSFL-LDCM.

-

(3)

Among the five evaluation metrics, SLR-LSF and SLR-LSF-SVM ranked mostly in the top in the average ranking, which proves that the algorithm proposed in this paper still has better experimental results on SVM classifiers. SLR-LSF-SVM combines the interval-maximizing linear classifier model with soft labels to further improve the algorithm’s classification performance. This also demonstrates that the SLR-LSF algorithm has strong robustness.

Comparison algorithm and parameter settings on the missing label

To demonstrate that the algorithm in this paper still has a good classification effect for missing labels, five state-of-the-art missing label algorithms are experimentally compared. \(\:\rho\:\) of the labels in the complete dataset are randomly selected as missing labels. \(\:\rho\:=0\) indicates that the label is complete. We choose HL, AP, OE, and RL metrics to reflect the performance of our algorithm. The parameters are set as follows:

-

(1)

The LSML18 algorithm recovers missing labels by learning higher-order LC matrices and LSF. The parameters are set to \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}={10}^{1}\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}={10}^{-5}\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}={10}^{-3}\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{4}={10}^{-5}\).

-

(2)

The JLCLS33 algorithm completes the missing labels by LC and learns LSF of the completed labels. The parameters \(\:\alpha\:,\:\:\beta\:,\:\:\theta\:,\:\:\gamma\:\) are searched in \(\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{10}\right]\), \(\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{10}\right]\), \(\:\left[{2}^{-10}{,2}^{10}\right]\), \(\:\left\{0.1,1,10\right\}\) respectively.

-

(3)

The GLOCAL19 algorithm recovers the missing labels by learning local and global LC in low-rank space with parameters set to \(\:\lambda\:=1\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\sim{\lambda\:}_{5}\in\:\left[{10}^{-1},{10}^{1}\right]\), \(\:k\in\:\left\{0.1\ell,0.2\ell,\dots\:,0.6\ell\right\}\), \(\:g\in\:\left\{\text{5,10,15,20}\right\}\).

-

(4)

The MNECM27 algorithm recovers the missing labels by measuring the LC through information entropy. Parameter \(\:C\) is set to 1 and the RBF kernel is used in the extreme learning machine.

-

(5)

The LRMML24 algorithm recovers the missing labels by low-rank label subspace transformation and global and local LC learning with parameters set to \(\:\delta\:=0.005\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{R},{\lambda\:}_{L}{,\lambda\:}_{T}\in\:\left\{{10}^{-10},{10}^{-9},\dots\:,{10}^{5}\right\}\).

Figures 2 and 3 present the experimental results of SLR-LSF and the comparison algorithms GLOCAL, LSML, MNECM, LRMML, and JLCLS, comprising a total of 128 experiments (4 metrics * 4 missing rates * 8 datasets). Across the HL, AP, and OE metrics, SLR-LSF outperforms the other five comparison algorithms significantly. In terms of the RL metric, SLR-LSF is slightly inferior to LRMML in terms of the number of superior experimental groups; however, it is still the second-best option for some non-superior datasets. This analysis indicates that the experimental performance of SLR-LSF is significantly better than that of other comparison algorithms. Like the other algorithms, the proposed method’s performance decreases as the missing rate increases. This is because as the missing rate increases, the label space becomes sparser, and there is less available information. Both SLR-LSF and MNECM use entropy-based methods to calculate a confidence matrix using known information, making them more dependent on the label space. SLR-LSF performs better than MNECM because it extracts class discriminative attributes by utilizing global and local correlations to complete the soft label matrix.

SLR-LSF outperforms JLCLS, LSML, and GLOCAL because they recover missing labels using LC and perform classification, while soft labels contain more semantic information and provide better experimental results than traditional logical labels. LRMML’s performance is closest to that of SLR-LSF because LRMML uses a label-assisted matrix to recover missing labels and perform classification, similar to our algorithm’s functionality. However, LRMML also performs classification using logical labels, resulting in lower experimental performance than SLR-LSF.

Analysis of the algorithm

Ablation analysis

We conducted an ablation analysis to demonstrate that the LSF learned by soft labels is superior to that learned by logic labels. The SLR-LSF algorithm was used to learn the LSF for soft labels, while the LR-LSF algorithm was used to learn the LSF for logic labels. We evaluated the performance of these two algorithms on 12 datasets using five metrics, as shown in Fig. 4. The results indicated that the performance of learning LSF from soft labels was significantly better than that of learning LSF from logic labels across all five metrics. This demonstrates that soft labels contain more semantic information than logic labels and can provide richer LSF.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

There are three important parameters in SLR-LSF. Parameter \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) is used to adjust the global correlation of label prediction, parameter \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\) is used to adjust the local smoothing term of label prediction, and parameter \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\) is used to adjust the sparsity of LSF. In our experiments, we tune the parameters on the Birds dataset, let one parameter vary within a certain range and fix the other parameters, and record all the experimental results. The effect of \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\), and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\) on the SLR-LSF algorithm is analyzed by the variation of HL, AP, OE, RL, and CV metrics. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 5. From this figure, we can observe that the variations of \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\) have little effect of the SLR-LSF algorithm, but when the value of \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\) is large, the performance of SLR-LSF algorithm becomes very poor, which is due to the selected features being too sparse. Therefore, we suggest setting the range of the parameters as follows: \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\in\:\left[{10}^{-10},{10}^{1}\right]\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\in\:\left[{10}^{-10},{10}^{1}\right]\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{3}\in\:\left[{10}^{-10},{10}^{0}\right]\).

Statistical hypothesis testing

In this paper, we first evaluate the SLR-LSF algorithm on each dataset using the Friedman test34. Supposing the number of experimental data sets is \(\:N\), the number of experimental algorithms is \(\:K\), and the sorting matrix \(\:R={\left[{r}_{1},{r}_{2},{r}_{3},\dots\:,{r}_{K}\right]}^{\mathbf{T}}\in\:{R}^{N\times\:K}\). \(\:S\) is obtained from Eq. (31). And the Friedman statistic \(\:{F}_{F}\) is found by applying the result of \(\:S\) in Eq. (32).

The obtained \(\:{F}_{F}\) is compared with the critical value of F test. If \(\:{F}_{F}\) is greater than the critical value, the null hypothesis is rejected; otherwise, the null hypothesis is accepted. The critical value of the F test was obtained by checking the table after calculating \(\:F\left(K-1,\left(K-1\right)\left(N-1\right)\right)\). The following table shows the result of the test with a significance level of α = 0.05.

From Tables 3 and 4, we can see that all evaluation metrics of the SLR-LSF algorithm on the complete and missing data set are much larger than the critical values, so all original hypotheses have been rejected. This proves that there is a significant difference between the proposed algorithm and other algorithms, which reflects the feasibility and effectiveness of the SLR-LSF algorithm.

The Nemenyi test35 at a significance level of \(\:\alpha\:=0.05\) is used to compare the performance of SLR-LSF with other algorithms on the several data sets. Two algorithms are considered to be significantly different when the difference between their average rankings is greater than the critical difference (CD). Conversely, there is no significant difference. The CD value is \(CD = q_{\alpha } \sqrt {K\left( {K + 1} \right)/6N}\). And in complete datasets \(\:{K}_{1}=7\), \(\:{N}_{1}=12\), \(\:{q}_{\alpha\:1}=2.9480\), \(\:{CD}_{1}=2.5999\) and in missing datasets \(\:{K}_{2}=6\), \(\:{N}_{2}=32\), \(\:{q}_{\alpha\:2}=2.8501\), \(\:{CD}_{2}=1.3330\). The comparison results of our proposed algorithm with five state-of-the-art complete algorithms and missing algorithms are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. From left to right, the performance of the algorithm decreases accordingly.

In the complete algorithm shown in Fig. 6, SLR-LSF and SLR-LSF-SVM rank first or second in all five metrics, with no significant differences between them. Regarding the HL metric, there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and GLSFL-LDCM. In terms of the AP and RL metrics, there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and LSR-LSF or GLSFL-LDCM. As for the OE metric, there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and LSR-LSF, GLSFL-LDCM, or LLSF. In the CV metric, there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and LSR-LSF. However, SLR-LSF differs significantly from other algorithms in all five metrics. In the missing algorithm shown in Fig. 7, we can see that there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and LRMML in the HL and OE metrics. In the AP and RL metrics, there is no significant difference between SLR-LSF and LRMML or GLOCAL. In addition, in all four metrics, SLR-LSF differs significantly from other algorithms. From the analysis of the above two statistical hypothesis tests, it is clear that SLR-LSF algorithm is significantly different from other algorithms, which further illustrates the effectiveness of our proposed algorithm.

Convergence analysis of SLR-LSF

In this paper, Arts and Computers datasets are selected for convergence analysis36. As can be seen from Fig. 8, the convergence trend is reached quickly on both datasets. We perform the same experiment on other datasets. The same is true on other datasets.

Conclusion

In this paper, the logical labels are converted into soft labels that can reflect the mapping relationship by combining the confidence matrix and the label density information. The obtained soft labels are then learned from LSF. Extensive experiments have demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. The strength of our proposed algorithm lies in the impact of the artificial division threshold on the datasets being reduced. Our proposed algorithm also has better results for datasets with missing labels. However, the weaknesses of this approach are equally obvious. Compared to other algorithms, using information entropy is more time-consuming. Conducting experiments at high missing rates always results in less effectiveness. Therefore, in future, we will try using graph-based approach to convert logical labels into soft labels to reduce the time-consuming. If the labels are heavily missed, only one-sided information can be obtained through the labels alone. Next, we will try to use the complete instance and feature information to recover the severely missing label information.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wei, W. et al. Automatic image annotation based on an improved nearest neighbor technique with tag semantic extension model. Procedia Comput. Sci.183, 616–623 (2021).

Qian, T. et al. Contrastive learning from label distribution: A case study on text classification. Neurocomputing507, 208–220 (2022).

Xia, W. Q. et al. PFmulDL: A novel strategy enabling multi-class and multi-label protein function annotation by integrating diverse deep learning methods. Comput. Biol. Med.145, 105465 (2022).

Liu, S. H., Wang, B., Liu, B. & Yang, L. T. Multi-community graph convolution networks with decision fusion for personalized recommendation. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, vol. 13282, 16–28 (2022).

Zhao, D. W. et al. Multi-label weak-label learning via semantic reconstruction and label correlations. Inf. Sci.623, 379–401 (2023).

Xu, N., Liu, Y. P. & Geng, X. Label enhancement for label distribution learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.33, 1632–1643 (2019).

Xu, N., Qiao, C. Y., Lv, J. Q., Geng, X. & Zhang, M. L. One positive label is sufficient: Single-positive multi-label learning with label enhancement. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS’22) 21765–21776 (2022).

Wang, F., Zhu, L., Li, J. J., Chen, H. B. & Zhang, H. X. Unsupervised soft-label feature selection. Knowl. Based Syst.219, 106847 (2021).

Jiang, Y. L., Weng, J. W., Zhang, X. T., Yang, Z. & Hu, W. J. A CNN-based born-again TSK fuzzy classifier integrating soft label information and knowledge distillation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst.31, 1843–1854 (2023).

Zhang, M. L. & Wu, L. Multi-label learning with label-specific features. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.37, 107–120 (2015).

Huang, J., Li, G. R., Huang, Q. M. & Wu, X. D. Learning label-specific features and class-dependent labels for multi-label classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.28, 3309–3323 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. Multi-label learning with label-specific features by resolving label correlations. Knowl. Based Syst.159, 148–157 (2018).

Wang, Y. B., Pei, G. S. & Cheng, Y. S. Group-label-specific features learning method based on label-density classification margin. J. Electron. Inform. Technol.42, 1179–1187 (2020).

Cheng, Y. S., Zhang, C. & Pang, S. F. Multi-label space reshape for semantic-rich label-specific features learning. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet.13, 1005–1019 (2022).

Li, W. W., Chen, J., Gao, P. X. & Huang, Z. Q. Label enhancement with label-specific feature learning. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet.13, 2857–2867 (2022).

Yu, H. F., Jain, P., Kar, P. & Dhillon, I. Large-scale multi-label learning with missing labels. In 2014 Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 32, 593–601 (2014).

Sun, Y. Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhou, Z. H. Multi-label learning with weak label. In 2010 AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 593–598 (2010).

Huang, J. et al. Improving multi-label classification with missing labels by learning label-specific features. Inform. Sci.492, 124–146 (2019).

Zhu, Y., Kwok, J. T. & Zhou, Z. H. Multi-label learning with global and local label correlation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.30, 1081–1094 (2017).

Wang, Y. B., Zheng, W. J., Cheng, Y. S. & Zhao, D. W. Two-level label recovery-based label embedding for multi-label classification with missing labels. Appl. Soft Comput.99, 106868 (2021).

Cheng, Y. S., Qian, K. & Min, F. Global and local attention-based multi-label learning with missing labels. Inform. Sci.594, 20–42 (2022).

Ma, J. H., Tian, Z. Y., Zhang, H. J. & Chow, T. W. S. Multi-label low-dimensional embedding with missing labels. Knowl. Based Syst.137, 65–82 (2017).

Ma, Z. C. & Chen, S. C. Expand globally, shrink locally: Discriminant multi-label learning with missing label. Pattern Recogn.111, 107675 (2021).

Kumar, S. & Rastogi, R. Low rank label subspace transformation for multi-label learning with missing labels. Inform. Sci.596, 53–72 (2022).

Miao, J. L., Wang, Y. B., Cheng, Y. S. & Chen, F. Parallel dual-channel multi-label feature selection. Soft. Comput.27, 7115–7130 (2023).

Cheng, Y. S., Zhao, D. W., Zhan, W. F. & Wang, Y. B. Multi-label learning of non-equilibrium labels completion with mean shift. Neurocomputing. 321, 92–102 (2018).

Cheng, Y. S., Qian, K., Wang, Y. B. & Zhao, D. W. Missing multi-label learning with non-equilibrium based on classification margin. Appl. Soft Comput.86, 105924 (2020).

Huang, J., Li, G. R., Huang, Q. M. & Wu, X. D. Learning label specific features for multi-label classification. In IEEE International Conference on Data Mining 181–190 (2015).

Ge, W. X., Wang, Y. B., Xu, Y. T. & Cheng, Y. S. Causality-driven intra-class non-equilibrium label-specific features learning. Neural Process. Lett.56, 120 (2024).

Lin, Z. et al. Fast convex optimization algorithms for exact recovery of a corrupted low-rank matrix. Coordinat. Sci. Lab. Rep.246, 2214 (2009).

Kumar, V., Pujari, A. K., Padmanabhan, V. & Kagita, V. R. Group preserving label embedding for multi-label classification. Pattern Recogn.90, 23–34 (2019).

Han, H. R., Huang, M. X., Zhang, Y., Yang, X. G. & Feng, W. G. Multi-label learning with label specific features using correlation information. IEEE Access19, 11474–11484 (2019).

Wang, Y. B., Zheng, W. J., Cheng, Y. S. & Zhao, D. W. Joint label completion and label-specific features for multi-label learning algorithm. Soft. Comput.24, 6553–6569 (2020).

Cheng, Y. S. et al. Multi-view multi-label learning for label-specific features via glocal shared subspace learning. Appl. Intell.54, 11054–11067 (2024).

Demsar, J. Statistical comparisons of classifiers over multiple data sets. J. Mach. Learn. Res.7, 1–30 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Gong, D. W., Sun, X. Y. & Guo, Y. N. A PSO-based multi-objective multi-label feature selection method in classification. Sci. Rep.7, 376 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology on Parallel and Distributed Processing Laboratory (No. WDZC202252501), National Natural Science Foundation of Anhui under Grant (No. 2108085MF216), Anqing Normal University Graduate Innovation Fund (No. 2021yjsXSCX017), Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Educational Committee of Anhui Province (No. 2024AH051099) and 2024 University Research Priorities (No. KJYB2024010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiansheng Jiang and Wenxin Ge; analysis and interpretation of results: Jiansheng Jiang, Yibin Wang and Yusheng Cheng; draft manuscript preparation: Wenxin Ge, Yuting Xu and Yibin Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J., Ge, W., Wang, Y. et al. Soft-label recover based label-specific features learning. Sci Rep 14, 23099 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72765-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72765-6