Abstract

Rationally designing distinct acidic and basic sites can greatly enhance performance and deepen our understanding of reaction mechanisms. In our current investigation, we studied the utilization of Brønsted acid sites within layered graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) for the first time to enhance the rate of the Friedländer synthesis. The structural and surface analyses confirm the effective integration of -COOH and -SO3H groups into the g-C3N4 lattice. The surface-functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H exhibits a remarkable acceleration in quinoline formation, surpassing previously mentioned catalysts, and demonstrating notable recyclability under optimized mild reaction conditions. The heightened reaction rate observed over g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H is attributed to its elevated surface acidity. By probing the Friedländer reaction mechanism through surface characterization, examination of reaction intermediates, and investigation of substrate scope, we elucidate the pivotal role of Brønsted acid sites. This study constitutes a comprehensive exploration of metal-free heterogeneous catalysts for the Friedländer reaction, offering a unique contribution to the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quinoline derivatives, commonly found in natural products exert significant influence in medicinal chemistry due to their diverse biological properties1,2,3,4. Additionally, their applications are also extended to polymer chemistry4,5, sensing6 and electrochemistry applications7,8. Despite the exploration of numerous methods, the Friedländer synthesis, discovered in 1882, remains one of the most straightforward approaches to generating polysubstituted quinolines (Fig. 1). This procedure typically involves the condensation and cycloaddition of 2-amino aryl ketones and α-methylene carbonyl derivatives, often catalysed by acids.

The Friedländer annulation, which involves the condensation and cyclodehydration of 2-amino aryl ketones and α-methylene carbonyl derivatives, are generally catalysed by classic homogeneous Brønsted acids such as hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, p-toluenesulfonic acid, and phosphoric acid9,10,11,12. However, the use of homogeneous acid catalysts has drawbacks, including solvent disposal, and waste generation. Heterogeneous acid catalysts have garnered significant attention in various fields of organic synthesis in recent years13,14,15. Recent studies, therefore have explored a variety of heterogeneous Lewis acids such as CeCl3·7H2O16, FeCl3, Mg(ClO4)217, Bi(OTf)318, Y(OTf)319, SnCl220, and In(OTf)321. However, these conventional heterogeneous catalysts encounter issues such as, significant mass transfer resistance, harsh reaction conditions, and susceptibility to the leaching of active sites. Researchers recently focused on developing alternate heterogeneous catalysts for Friedländer synthesis to achieve desired results under milder conditions, and the catalysts, such as as zeolites, metal-organic frameworks, mesoporous silica, zirconia have been explored22,23,24,25. In our previous work, Brønsted acid functionalized metal-organic framework material MIL-53(Al)-SO3H exhibited a very high yield of quinoline under solventless and mild reaction conditions, with a wide substrate scope and good reusability26,27.

Very recently, there has been significant interest in the applications of two-dimensional materials in catalysis28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. g-C3N4 emerges as a particularly significant two-dimensional material, characterized by van der Waals forces between layers composed of tri-s-triazine units interconnected by plane tertiary amino groups36,37. g-C3N4 has attracted attention due to its cost-effectiveness, accessibility, environmental friendliness, and status as a non-metallic organic catalyst38. In this work, we present an innovative method for incorporating Brønsted acid sites into g-C3N4. For the first time, the potential of this metal-free, environmentally friendly green heterogeneous catalyst is studied ameliorating the rate of Friedländer synthesis.

Experimental section

To synthesize the pristine and functionalized g-C3N4, the precursors, such as melamine, 1,3-propanesultone, and glutaric anhydride were purchased from TCI Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. The solvents, including N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), chloroform (CHCl3), isopropyl alcohol (IPA), methanol (MeOH), ethanol (EtOH) and toluene were purchased from Merck Specialties Pvt. Ltd. (India). The Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) solvents, D2O (99.9%), d6-CDCl3 and d6-DMSO were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. For catalytic reactions,2-aminobenzaldhyde, 2-amino Benzophenone, 2-amino-5-chlorobenzophenone, 2-amino-5-nitrobenzophenone, 2-amino-2’,5-dichlorobenzophenone, acetylacetone, ethyl acetoacetate, cyclohexanone, and other necessary chemicals were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. The synthesized compounds were purified with silica gel (60–120 mesh pore size), ethyl acetate and hexane from Avra Synthesis Pvt. Ltd. (India).

The bulk g-C3N4 was produced by heating melamine at a temperature of 550 °C for a duration of 4 h, with a heating rate of 2.3 °C per minute. The obtained g-C3N4 was collected and crushed using a mortar and pestle29. For synthesis of g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H, 300 mg of the as-prepared g-C3N4 was suspended in 5 mL of toluene, followed by the addition of 600 mg of glutaric anhydride into the mixture. The mixture was refluxed under magnetic stirring for 24 h, and the sample was filtered off and washed three times with toluene, EtOH, and H2O to remove the unreacted glutaric anhydride. The functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H was dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C overnight, yielding 310 mg of product. To synthesize g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H, the as-prepared g-C3N4 (300 mg) was suspended in 5 mL of toluene within a 50 mL round-bottom flask. Following this, 600 mg of 1,3-propanesultone was introduced into the mixture. The mixture was refluxed using magnetic stirring for 24 h, and filtered and washed the sample three times with toluene, EtOH, and H2O to remove any unreacted 1,3-propanesultone. The functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H was dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C overnight, yielding 380 mg of product.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies and phase analysis on the synthesized materials were conducted using a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at a scan rate of 1 o/min and step size of 0.01 o. The average crystalline diameters (D) were determined using Scherrer’s formula: \(\:\text{D}=\frac{0.9{\uplambda\:}}{{\upbeta\:}\text{C}\text{O}\text{S}{\uptheta\:}}\), where 0.9 is the shape factor, β is the full-width at half-maxima, λ is the X-ray wavelength, and θ is the corresponding angle. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of the synthesized samples were obtained using a JASCO 4200 spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The thermal decomposition of the catalysts was evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a Shimadzu DTG-60 under an N2 atmosphere, with a scan rate of 10 oC/min within the temperature range of 30–600 oC. To determine the surface morphology of the samples, a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, FEI-Apero S) was utilized. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected using a Thermo Scientific K-ALPHA surface analysis spectrometer with Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) to examine the chemical bonding and surface elemental state of the as-synthesized catalyst. The binding energy of the other elements was adjusted with reference to C 1s of 284.8 eV and elemental analysis was done by using CHNS analysis to find the ratio of sulphur on functionalized g-C3N4.

To prepare the target quinoline derivatives, 2-aminoaryl ketones (1.0 mmol) and α-methylene carbonyl derivatives (1.2 mmol) were dissolved in a solvent, or without a solvent. Pristine and modified g-C3N4 catalysts, containing 10 wt% relative to 2-aminoaryl ketone, were added to the reactants. The reaction mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 4–6 h, while the temperature was varied from 25 to 100 °C. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC, using a mobile phase of 20% ethyl acetate in hexane and quantitative NMR using 1,3,5 trimethoxy benzene as internal standard. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was cooled, and the solid catalyst was separated by centrifugation using dichloromethane. The structure was analysed by1H-NMR using an AV NEO 400 MHz (Bruker) and LC-MS using a Shimadzu-8040. The recovered catalyst was tested for recyclability for up to five cycles. The reaction conditions were optimized by varying the catalyst loading, reaction temperature, time, solvents, and substrate scope.

Results and discussion

Structure and surface properties

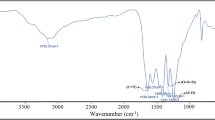

The successful synthesis of pristine g-C3N4 and functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H was confirmed through powder X-ray diffraction. g-C3N4 was synthesized from melamine, followed by a reaction with glutaric anhydride and 1,3-propanesultone to yield crystalline g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, as shown in Fig. 2a. In Fig. 2(b), data reveal distinct diffraction peaks from pristine g-C3N4 at 2θ = 12.4° and 27.6°, corresponding to the (100) and (002) planes, respectively. The (100) plane signifies the in-plane structural39 packing of tri-s-triazine or heptazine units, with an interlayer distance of 0.675 nm, while the (002) plane corresponds to the stacked conjugated aromatic rings between layers, with an interlayer spacing of 0.326 nm29,39,40,41. The powder XRD patterns of the Brønsted acid-functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H catalysts exhibit similar peaks to g-C3N4, indicating remarkable structural consistency after functionalization. The nanocrystalline diameters of both pristine and functionalized g-C3N4 were calculated using Scherer’s formula, resulting in an average size range of 4 to 5 nm. The FTIR spectra in Fig. 2(c), further confirm the chemical structures of the g-C3N4 and acid functionalized g-C3N4. The functionalized g-C3N4 exhibited major characteristic IR spectra similar to bulk g-C3N4. The characteristic peaks in the region 1200–1650 cm− 1 correspond to N–(C)3 and C–N = C stretching vibrations42,43, confirmed that the basic functional units are retrained after functionalization on g-C3N4. The sharp peak at 810 cm− 1 is attributed to tri-s-triazine ring vibrations44,45. In g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, the surface functionalization was further evidenced by the characteristic peaks at 1169 cm− 1 and 1033 cm− 1 ascribed to asymmetric and symmetric stretching of S = O groups, respectively46. The band at 1711 cm− 1 present only in g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H is due to the stretching frequency of C = O in the free carboxylic group. The powder XRD and the FTIR studies confirmed the successful synthesis of bulk g-C3N4 and their functionalized derivatives. From the CHNS analysis (Table S1) we determined that 20% of g-C3N4 has been functionalized with -SO3H.

The thermogravimetric analysis was conducted up to 500 oC to evaluate the thermal stability of pristine and functionalized g-C3N4 catalysts. The TGA results displayed in Fig. 3 exhibit a minor weight loss on the functionalized materials compared to pristine g-C3N4, attributed to the presence of surface functionality. The g-C3N4 bulk catalyst exhibited remarkable stability within the experimental temperature window with a minimal weight loss of 3.0% due to the desorption of physisorbed surface bound species. The g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H exhibited ~ 20% weight loss starting at 150 °C, whereas g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H exhibited a total weight loss of 10%. It is evident from the TGA studies that the stability of functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H is superior to g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H44. The higher stability of g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H could be attributed to the strong N-C bond with respect to the amide type bond in g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H47,48. Additionally, the thermal stability exhibited by the functionalized catalysts is adequate for conducting the Friedländer synthesis reaction at elevated temperatures.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was used to analyse the elemental chemical states of the composite of g-C3N4 and functionalized g-C3N4 catalysts (Fig. 4). The XPS survey spectra of the materials in Fig. 4a demonstrate the existence of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen in all the three catalysts, along with sulphur in g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. The C 1s spectra in Fig. 4(b) deconvoluted in four components. The primary peak at 284.8 eV represents the adventitious carbon from impurities and/or sp3C from g-C3N428,49. The second peak at 286.0 eV is associated with C-NH2 species44. Two additional peaks with higher binding energies, at 287.9 and 288.3 eV are attributed to N = C-N coordination and the N-C-O groups, respectively50,51. After functionalization, the binding energies of C1s of N = C-N and N-C-O species apparently shifts to higher binding energy value owing to the electronegative functional group attachment. In Fig. 4c, the deconvoluted N 1s spectra of pristine g-C3N4 reveal three peaks at 400.8, 399.6 and 398.1 eV corresponding to the C-NHx, N-(C)3, and C-N = C bonding structures, respectively40. Interestingly, the N 1s XPS spectra of functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H catalysts exhibit similar peaks at higher binding energies of 402.0, 400.7, and 399.5 eV. As a result of –SO3H, -COOH functionalization, the peaks corresponding to s-triazine units in C-1s and N-1s XPS spectra of functionalized g-C3N4 nanosheets are shifted to the higher binding energies as compared to pristine g-C3N452. Figure 4(d) shows the XPS spectrum of O 1s in functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. The oxygen atoms in S-OH and S = O were observed at 531.6 eV and 533.0 eV, respectively53. Figure 4(e) displays the S 2p XPS spectrum of functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. The deconvoluted peaks at 168.0 eV and 168.9 eV correspond to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2, respectively from the -SO3H group44,54.

FE-SEM analyses presented in Fig. 5(a–c) elucidated the morphology of pristine g-C3N4 and functionalized g-C3N4 catalysts. g-C3N4 exhibited aggregated and crumbled sheet-like morphology, while g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H along with g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H displayed a stacked sheet morphology. The BET analysis was carried out to measure the surface area of g-C3N4, functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H catalysts. The nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms of the three synthesized catalysts are shown in Fig. 5d. These isotherms exhibited a characteristic Type IV physisorption pattern and an H3 hysteresis loop. Based on the Brunauer-Deming-Teller classification, the g-C3N4 and functionalized-g-C3N4 catalysts have slit-shaped mesopores that resulted from the stacking of thin nanosheets55. The surface area of the g-C3N4 catalyst was 23.53 m2 g− 1, whereas g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H exhibited a surface area of 14.26 and 31.19 m2 g− 1, respectively. The mean pore size for g-C3N4, functionalized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H catalysts was found in the range of 35.00 to 42.00 nm, whereas the mean pore volume for each catalyst was in the range of 0.15 to 0.29 cm3 g− 1.

Catalytic activity

The thoroughly characterized catalysts were screened for synthesis of biologically and physiologically attractive quinoline derivatives from 2-aminoarylketone with acetyl acetone. Initially, catalysts were studied under consistent experimental conditions, specifically without any solvent at a temperature of 100 °C for 4 h of duration. Quantitative NMR analysis with an internal standard 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was carried out to determine the conversion and yield of the reaction. The catalytic results are shown in Fig. 6. The pristine g-C3N4 material facilitated the conversion of 49% of the 2-aminoarylketone, resulting in a 45% yield of the desired product, while the control experiment without any catalyst yielded only 19% of quinoline, with a 23% conversion of 2-aminoarylketone. Apparently, the catalyst played a crucial role in the Friedländer synthesis of quinoline, as demonstrated by the results. The rate of reaction over the pristine g-C3N4 was determined to be 1.19 × 10− 6 mol g− 1 s− 1. Further catalytic screenings were conducted using Bronsted acid functionalized g-C3N4 catalysts. It is apparent from Fig. 6 that g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H could has a marginally impact on enhancing the conversion rate of 2-aminoarylketone to 57% and increasing the yield of quinoline to 49%. Remarkably, g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H demonstrated exceptional efficiency, achieving a 98% conversion rate of 2-aminoarylketone to quinoline, accompanied by a notably elevated yield of 97%. The calculated rate was 1.19 × 10− 6 and 2.77 × 10− 5 mol g− 1 s− 1 over g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, respectively. The atom economy of the conversion of 2-aminoarylketone to the corresponding quinoline over g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H without considering the water was found to be 90.13%. The findings piqued our interest to compare the effectiveness of our material with the catalysts reported in the open literature. Table 1 provides a summary of the efficiency of acid-based heterogeneous catalysts in the Friedländer synthesis of quinoline. The investigations in the table demonstrate an operational reaction temperature of 100 °C or less, with or without solvents. Remarkably, g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H demonstrated exceptional performance, surpassing the catalysts mentioned in previous studies.

Apparently, the pivotal acid sites play a vital role in augmenting the Friedländer synthesis of quinoline, as also suggested by the results from Table 1. Therefore, evaluation of strength of the acid site of the catalysts is very important for corelating the conversion efficiency of 2-aminoarylketone in quinolines. The potentiometric titration technique was used to evaluate the acidity potency of the synthesized pristine and functionalized g-C3N4 catalysts. This method evaluates the acidity of the catalyst, making it possible to determine the total number of acidic sites in addition to the strength of each individual site. The initial electrode potential (E in mV) was employed for assessing the strength of acid sites (in M.eq/g solid catalyst), and Fig. 7 shows the titration curves for the synthesised catalysts. These acid sites are categorized into four groups: E > 100 mV (indicating very strong acid sites), 0 < E < 100 mV (representing moderate acid sites), -100 < E < 0 mV (characterizing weak acid sites), and E < -100 mV (signifying very weak acid sites)61,62. The results clearly demonstrated that g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H exhibited an exceptionally high initial electrode potential of 549 mV, indicative of the presence of very strong Brønsted acid sites. On the contrary, the initial electrode potentials of g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and pristine g-C3N4 were 143 mV and − 44 mV, respectively, indicating the presence of moderate and weak acid sites over the materials. The findings of the acid strength rationalize the effectiveness of converting 2-aminoarylketone and yield of quinoline over pristine g-C3N4 and acid functionalized g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H.

As g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H turned out to be the best catalyst for synthesis of quinoline from 2-aminoarylketone, further the reaction conditions were optimized with this catalyst by changing the solvents, reaction temperature, duration, and catalyst loading. To optimise the solvent condition, the catalytic reactions were conducted with 10.0 wt% of g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst loading for 4 h of duration. Commercially available solvents, such as ethanol (EtOH), Methanol (MeOH), Isopropanol (IPA), acetonitrile (ACN), toluene and N, N dimethyl formamide (DMF) were investigated. Figure 8(a) shows 2-aminoaryl ketone conversion and quinoline yield against different solvents. Among the solvents investigated, ethanol, methanol, and DMF demonstrated a yield of 40–60% for quinoline. In contrast, toluene and acetonitrile showed lower conversion rates for 2-aminoaryl ketones to quinoline derivative. The highest reactivity of g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H was observed in the absence of a solvent with a product yield of 97% and 98% conversion of 2-amino aryl ketone. Therefore, the subsequent experiments were aimed at optimising the reaction conditions without any solvent. Figure 8(b) shows the percentage yield of quinoline without any solvent at different temperatures for 4 h of duration. The conversion of 2-aminoarylketone was initially minimal at room temperature. With a systematic increase of temperature by 25 °C for each successive experiment, the highest yield of quinoline was observed at 100 °C. Consequently, the reaction temperature was optimised at 100 °C thereafter. Further, the reaction duration was varied from 0.5 to 5.0 h under solvent-free conditions while keeping the reaction temperature constant at 100 °C over 10.0% g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. Figure 8(c) displays that a duration of 4 h is the optimal time for the Friedländer synthesis of quinoline. Finally, the optimisation of the g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst loading was achieved by changing the weight% from 0 to 10.0%. The results shown in Fig. 8(d) indicate that there is minimal advancement of the reaction in the absence of catalysts under the given reaction conditions. A 10.0 wt% loading of the g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst achieved the best percentage yield of quinoline.

The optimisation experiments revealed that a 10 wt% loading of g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst at 100 °C could maximise quinoline yield under solvent-free conditions in 4 h of reaction time. When considering the possible practical applications, the main benefit of using heterogeneous acid catalysts is their reusability and stability, in addition to their greater catalytic activity. Therefore, the recyclability of the catalysts g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H under the optimised reaction conditions for up to 6 cycles was investigated. After each catalytic cycle, the catalyst was retrieved by centrifugation, using dichloroethane, and subsequently was dried under normal atmospheric conditions. Figure 9 demonstrates the recyclability of the exhausted catalyst, indicating that the catalytic activity remains intact for up to 6 consecutive cycles. The yield of quinoline was marginally dropped from 97 to 87%. After six cycles, the XRD, XPS, FE-SEM, FTIR and CHNS tests revealed that the catalyst retained its structure, morphology, and surface chemical compositions (Table S1, and Figure S1). The potentiometric titration experiment exhibited a marginal loss of acid strength in the exhausted catalyst. The synthesized g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H with Brønsted acid functionality demonstrated remarkable stability throughout numerous catalytic cycles.

Further experiments were carried out to evaluate the scope of the substrate of the reaction with respect to various α-methylene carbonyl and 2-aminoaryl ketone compounds over the best catalysts g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H at optimized reaction conditions. Different substituted α-methylene carbonyl derivatives were reacted with 2-aminoaryl ketone substituted derivatives, and the NMR and MS data were utilised to characterise all the obtained products (Figures S2-S25), with results summarized in Table 2. When compared with unsubstituted 2-aminoaryl ketone, the yield of quinoline was slightly lower in 2-aminoaryl ketone that has a halogen or nitro group in para position to the amino group on the aromatic ring. When 2-aminobenzaldehyde or 2-aminoacetophenone were reacted instead of 2-aminobenzophenone in the reaction with acetylacetone, the resulting quinoline derivatives were obtained with yields of 77% and 86%, respectively. The corresponding quinoline derivative yield decreased from 97 to 86% when 2’,5-dichlorobenzophenone was combined with ethyl acetoacetate instead of acetyl acetone. Similarly, when ethyl acetoacetate was used instead of acetyl acetone in the reaction with 2-aminoacetophenone, a decrease in yield of the corresponding quinoline derivative from 86 to 80% was observed. When reacting with 2’,5-dichlorobenzophenone, six-membered cyclohexanone and 1,3-dicyclohexanone showed a comparable percentage yield of the desired product (~ 96%) among the cyclic ketones. The high yield observed may be attributed to the stabilization of nucleophiles by six-membered ring ketones. This pattern was consistent in the synthesis of quinoline derivatives when 2-aminoacetophenone reacted with six-membered cyclic ketones as well. However, the presence of ring strain in the five-membered cyclopentanone led to a lower yield of 85% compared to the equivalent quinoline derivative. Interestingly, phenyl substituted α-methylene carbonyl substrates exhibited lower yield of quinoline due to the electro withdrawing nature of the aromatic ring. Our analysis of the likely reaction mechanism is aided by this substrate’s scope investigations.

Numerous experimental and theoretical studies have investigated the Friedländer reaction mechanism over homogeneous as well as metal containing heterogeneous acid catalysts63,64. We probed the Friedländer reaction’s working mechanism over the synthesized metal-free heterogeneous catalyst, g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H with the help of the surface characterization data of the catalyst, reaction intermediates and substrate scope studies. The hot filtration experiments were carried out to establish the importance of the Brønsted acid sites of the g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. After 15 min of the commencement of the reaction in the optimized condition, the catalyst was removed from the reaction mixture by filtration using a hot frit, resulting in only 33% conversion of 2-aminoaryl ketone. The filtrate was then monitored for an additional 4 h to evaluate reaction progress using quantitative1HNMR. The results (Fig. 10) demonstrate that after the removal of the active catalyst, the reaction did not proceed, establishing the importance of the Brønsted acid sites of the catalyst g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H.

In order to obtain the stable reaction intermediates, the Friedländer reaction was conducted under optimized experimental conditions over g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H for four hours at room temperature, and the intermediates were examined using LCMS and HPLC methods. Based on the experimental observation, a probable mechanism is shown in Fig. 11. At the beginning, the reactant acetyl acetone may adsorb on the g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst surface through formation of hydrogen bond with C-NHx of g-C3N4. The terminal tri-s-triazine unit of g-C3N4 comprises different types of nitrogen such as (i) pyridinic nitrogen, (ii) graphitic nitrogen, (iii) oxidic nitrogen, (iv) tertiary and Lewis based nitrogen, and (v) pyrrolic nitrogen as presented schematically in the figure below. The various N-species in g-C3N4 are demonstrated to be very effective for catalytic reactions as they impart H-bonding, tunable basicity, Lewis acidity. It should be noted that the existence of C-NHx species was found to be highest over g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H from XPS studies. The following step is condensation of amine group in 2-aminoaryl ketone derivative and acetyl acetone with the help of protonation from the Brønsted sites of the catalyst g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H, leading to imine intermediate, which can tautomerize to enamines. The LCMS and HPLC data identified the formation of imine intermediate (Figure S26). The intramolecular aldol reaction in the next step produces the cyclized intermediate, which eventually loses water and yields the anticipated quinoline derivative. The reaction scheme prominently shows the importance of the Brønsted acid sites present in g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H. The -SO3H group in g-C3N4-(CH2)3-SO3H played a pivotal role in both the imine production and the cyclization processes.

Conclusion

g-C3N4 was successfully synthesized from melamine, followed by reactions with glutaric anhydride and 1,3-propanesultone, resulting in crystalline g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-CO2H and g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H, as confirmed by powder XRD and FTIR studies. Surface functionalization of g-C3N4 was further supported by detailed XPS analysis. Additional studies revealed no alteration in surface area, porosity after surface functionalization. The Friedländer synthesis of quinoline over pristine g-C3N4 showed a rate of 1.19 × 10− 6 mol g− 1 s− 1, while an order of magnitude higher rate of 2.77 × 10− 5 mol g− 1 s− 1 was observed over the g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst. This rate surpassed catalysts mentioned in previous studies, with notable recyclability. The high rate of Friedländer synthesis over g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H was attributed to its high surface acidity, as determined by potentiometric titration. Optimization experiments revealed that a 10 wt% loading of g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H catalyst at 100 °C maximized quinoline yield under solvent-free conditions within 4 h of reaction time. The Friedländer reaction mechanism over the synthesized metal-free heterogeneous catalyst, g-C3N4-CO-(CH2)3-SO3H, was probed using surface characterization data, reaction intermediates, and substrate scope studies. This study represents a unique and comprehensive exploration of metal-free heterogeneous catalysts for the Friedländer reaction.

Supporting information summary

Supporting Information includes CHNS analysis1, H -NMR and13C- NMR, HPLC, LCMS, and the powder XRD, XPS and FE-SEM.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Solution, S. & Phillips, D. 2,4-Diamino-6,7-dimethoxyquinoline derivatives as. J. Med. Chem. 31, 1031–1035 (1988).

Giardina, G. A. M. et al. Discovery of a novel class of selective non-peptide antagonists for the human neurokinin-3 receptor. 1. Identification of the 4-quinolinecarboxamide framework. J. Med. Chem. 40, 1794–1807 (1997).

Lai, Y. Y. et al. Synthesis of gingerdione derivatives as potent antiplatelet agents. Chin. Pharm. J. 54, 259–269 (2002).

Zhang, X., Shetty, A. S. & Jenekhe, S. A. Electroluminescence and photophysical properties of polyquinolines. Macromolecules. 32, 7422–7429 (1999).

Jenekhe, S. A., Lu, L. & Alam, M. M. New conjugated polymers with donor-acceptor architectures: Synthesis and photophysics of carbazole-quinoline and phenothiazine-quinoline copolymers and oligomers exhibiting large intramolecular charge transfer. Macromolecules. 34, 7315–7324 (2001).

Mondal, S., Krishna, B., Roy, S. & Dey, N. Discerning toxic nerve Gas agents Via Distinguishable ‘Turn-On’ fluorescence response: Multi Stimuli Responsive quinoline derivatives in-action. Analyst. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4an00072b (2024).

Agrawal, A. K. & Jenekhe, S. A. Synthesis and processing of heterocyclic polymers as electronic, optoelectronic, and nonlinear optical materials. 3. New conjugated polyquinolines with electron-donor or -acceptor side groups. Chem. Mater. 5, 633–640 (1993).

Jégou, G. & Jenekhe, S. A. Highly fluorescent poly(arylene ethynylene)s containing quinoline and 3-alkylthiophene. Macromolecules. 34, 7926–7928 (2001).

Edward, A. & Fehnel Friedlander syntheses with o-Aminoaryl ketones. I. Acid-catalyzed condensations of o-Aminobenzophenone with ketones. J. Org. Chem. 31, 2899–2902 (1966).

Wang, G. W., Jia, C. S. & Dong, Y. W. Benign and highly efficient synthesis of quinolines from 2-aminoarylketone or 2-aminoarylaldehyde and carbonyl compounds mediated by hydrochloric acid in water. Tetrahedron Lett. 47, 1059–1063 (2006).

Shaabani, A., Soleimani, E. & Badri, Z. Triflouroacetic acid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of quinoline. Synth. Commun. 37, 629–635 (2007).

Jia, C. S., Zhang, Z., Tu, S. J. & Wang, G. W. Rapid and efficient synthesis of poly-substituted quinolines assisted by p-toluene sulphonic acid under solvent-free conditions: Comparative study of microwave irradiation versus conventional heating. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 104–110 (2006).

Clark, J. H. Solid acids for green chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 791–797 (2002).

Krishna, B. & Roy, S. Synthesis of 2,2,4-trimethyl-1,2-dihydroquinolines over metal-modified 12-tungstophosphoric acid-supported γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Res. Chem. Intermed. 46, 4061–4077 (2020).

Krishna, B., Payra, S. & Roy, S. Synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones via multicomponent reaction route over acid functionalized metal-organic framework catalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 607, 729–741 (2022).

Bose, D. S. & Kumar, R. K. An efficient, high yielding protocol for the synthesis of functionalized quinolines via the tandem addition/annulation reaction of o-aminoaryl ketones with α-methylene ketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 47, 813–816 (2006).

Wu, J., Zhang, L. & Diao, T. N. An expeditious approach to quinolines via Friedländer synthesis catalyzed by FeCl3 or Mg(ClO4)2. Synlett 2653–2657 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-917111

Yadav, J. S., Reddy, B. V. S. & Premalatha, K. Bi(OTf)3-catalyzed Friedländer hetero-annulation: a rapid synthesis of 2,3,4-trisubstituted quinolines. Synlett. 963–966. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-822898 (2004).

De, S. K. & Gibbs, R. A. A mild and efficient one-step synthesis of quinolines. Tetrahedron Lett. 46, 1647–1649 (2005).

Arumugam, P., Karthikeyan, G., Atchudan, R., Muralidharan, D. & Perumal, P. T. A simple, efficient and solvent-free protocol for the friedländer synthesis of quinolines by using SnCl2·2H2O. Chem. Lett. 34, 314–315 (2005).

Kumar, D. et al. In(OTf)3-catalyzed synthesis of 2-styryl quinolines: Scope and limitations of metal Lewis acids for tandem Friedländer annulation-knoevenagel condensation. RSC Adv. 5, 2920–2927 (2015).

Das, B., Damodar, K., Chowdhury, N. & Kumar, R. A. Application of heterogeneous solid acid catalysts for Friedlander synthesis of quinolines. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 274, 148–152 (2007).

Das, B., Krishnaiah, M., Laxminarayana, K. & Nandankumar, D. Silica supported phosphomolybdie acid: An efficient heterogeneous catalyst for friedlander synthesis of quinolines1). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 56, 1049–1051 (2008).

Shaabani, A., Rahmati, A. & Badri, Z. Sulfonated cellulose and starch: New biodegradable and renewable solid acid catalysts for efficient synthesis of quinolines. Catal. Commun. 9, 13–16 (2008).

Pérez-Mayoral, E. et al. Synthesis of quinolines via Friedländer reaction catalyzed by CuBTC metal-organic-framework. Dalt Trans. 41, 4036–4044 (2012).

Krishna, B. & Roy, S. Efficient synthesis of quinolines from 2-aminoaryl ketones with α-methylene carbonyl derivatives: exploiting the dual acid sites of metal organic framework catalyst. ChemistrySelect 8, (2023).

Krishna, B. & Roy, S. Synthesis of quinolines from 2-amino aryl ketones: Probing the Lewis acid sites of metal-organic framework catalyst. J. Chem. Sci. 136, 12–16 (2024).

Chandrasekharan Meenu, P. et al. Polyaniline supported g-C3N4 quantum dots surpass benchmark Pt/C: Development of morphologically engineered g-C3N4 catalysts towards metal-free methanol electro-oxidation. J. Power Sources. 461, 228150 (2020).

Challagulla, S., Payra, S., Chakraborty, C. & Roy, S. Determination of band edges and their influences on photocatalytic reduction of nitrobenzene by bulk and exfoliated g-C3N4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 3174–3183 (2019).

Roy, S. Tale of two layered Semiconductor catalysts toward artificial photosynthesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 37811–37833 (2020).

Li, K., Liu, Y. F., Lin, X. L. & Yang, G. P. Copper-containing polyoxometalate-based metal – Organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts for the synthesis of N–Heterocycles. Inorg. Chem. 61, 6934–6942 (2022).

Li, H., Pan, H., Fan, Y., Bai, Y. & Dang, D. Syntheses, crystal structures, and properties of four polyoxometalate-based metal–organic frameworks based on Ag(I) and 4,4′-dipyridine-N,N′-dioxide. Polyoxometalates. 1, 9140007 (2022).

Xie, Z. et al. Chemistry, Functionalization, and applications of recent Monoelemental two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Chem. Rev. 122, 1127–1207 (2022).

Guengerich, F. P. et al. Copper-containing polyoxometalate-based metal – Organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts for the synthesis of N–heterocycles. Polyoxometalates. 13, 1–10 (2022).

Li, Z. & Wu, Y. 2D early transition metal carbides (MXenes) for catalysis. Small. 15, 1–10 (2019).

Rashidizadeh, A., Ghafuri, H., Zand, E., Goodarzi, N. & H. R. & Graphitic Carbon Nitride nanosheets covalently functionalized with biocompatible vitamin B1: Synthesis, characterization, and its Superior performance for synthesis of Quinoxalines. ACS Omega. 4, 12544–12554 (2019).

Hosseini, S. & Azizi, N. CSA@g-C3N4 as a novel, robust and efficient catalyst with excellent performance for the synthesis of 4H-chromenes derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–16 (2023).

Lin, Q. et al. Efficient synthesis of monolayer carbon nitride 2D nanosheet with tunable concentration and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activities. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 163, 135–142 (2015).

Wang, A., Wang, C., Fu, L., Wong-Ng, W. & Lan, Y. Recent advances of graphitic carbon nitride-based structures and applications in catalyst, sensing, imaging, and leds. Nano-Micro Lett. 9, 1–21 (2017).

Zhu, Z., Pan, H., Murugananthan, M., Gong, J. & Zhang, Y. Visible light-driven photocatalytically active g-C3N4 material for enhanced generation of H2O2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 232, 19–25 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. Fabrication of atomic single layer graphitic-C3N4 and its high performance of photocatalytic disinfection under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 152–153, 46–50 (2014).

Niu, P., Zhang, L., Liu, G. & Cheng, H. M. Graphene-like carbon nitride nanosheets for improved photocatalytic activities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 4763–4770 (2012).

Pawar, R. C. et al. Room-temperature synthesis of nanoporous 1D microrods of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) with highly enhanced photocatalytic activity and stability. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–14 (2016).

Chhabra, T., Bahuguna, A., Dhankhar, S. S., Nagaraja, C. M. & Krishnan, V. Sulfonated graphitic carbon nitride as a highly selective and efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the conversion of biomass-derived saccharides to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in green solvents. Green. Chem. 21, 6012–6026 (2019).

Lotsch, B. V. et al. Unmasking melon by a complementary approach employing electron diffraction, solid-state NMR spectroscopy, and theoretical calculations - structural characterization of a carbon nitride polymer. Chem. - Eur. J. 13, 4969–4980 (2007).

Douzandegi Fard, M. A., Ghafuri, H. & Rashidizadeh, A. Sulfonated highly ordered mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride as a super active heterogeneous solid acid catalyst for Biginelli reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 274, 83–93 (2019).

Kovács, E., Rózsa, B., Csomos, A., Csizmadia, I. G. & Mucsi, Z. Amide activation in ground and excited states. Moleculess 23, (2018).

Guengerich, F. P. & Yoshimoto, F. K. Formation and cleavage of C-C bonds by enzymatic oxidation-reduction reactions. Chem. Rev. 118, 6573–6655 (2018).

Fujimoto, A., Yamada, Y., Koinuma, M. & Sato, S. Origins of sp3C peaks in C1s X-ray photoelectron spectra of carbon materials. Anal. Chem. 88, 6110–6114 (2016).

Li, H. et al. Construction of a well-dispersed Ag/graphene-like g-C3N4 photocatalyst and enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 7, 8688–8693 (2017).

Long, B., Lin, J. & Wang, X. Thermally-induced desulfurization and conversion of guanidine thiocyanate into graphitic carbon nitride catalysts for hydrogen photosynthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2, 2942–2951 (2014).

Verma, S., Baig, R. B. N., Nadagouda, M. N., Len, C. & Varma, R. S. Sustainable pathway to furanics from biomass: Via heterogeneous organo-catalysis. Green. Chem. 19, 164–168 (2017).

Wei, Y. et al. A facile approach toward preparation of sulfonated multi-walled carbon nanotubes and their dispersibility in various solvents. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 482, 507–513 (2015).

Duesberg, G. S. et al. Hydrothermal functionalisation of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Synth. Met. 142, 263–266 (2004).

Gregg, S. J. & Jacobs, J. An examination of the adsorption theory of Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller, and Brunauer, Deming, Deming and Teller. Trans. Faraday Soc. 44, 574–588 (1948).

Palakshi Reddy, B., Iniyavan, P., Sarveswari, S. & Vijayakumar, V. Nickel oxide nanoparticles catalyzed synthesis of poly-substituted quinolines via Friedlander hetero-annulation reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 25, 1595–1600 (2014).

Chan, C. K., Lai, C. Y. & Wang, C. C. Environmentally friendly nafion-mediated Friedländer Quinoline synthesis under microwave irradiation: application to one-Pot synthesis of substituted Quinolinyl Chalcones. Synth. 52, 1779–1794 (2020).

Yadav, J. S., Reddy, B. V. S., Sreedhar, P., Rao, R. S. & Nagaiah, K. Silver phosphotungstate: a novel and recyclable heteropoly acid for Friedländer quinoline synthesis. Synthesis (Stuttg). 2381–2385. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-831185 (2004).

Garella, D. et al. Fast, solvent-free, microwave-promoted Friedländer annulation with a reusable solid catalyst. Synth. Commun. 40, 120–128 (2010).

Yadav, J. S. et al. Sulfamic acid: An efficient, cost-effective and recyclable solid acid catalyst for the Friedlander quinoline synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 46, 7249–7253 (2005).

Villabrille, P., Vázquez, P., Blanco, M. & Cáceres, C. Equilibrium adsorption of molybdosilicic acid solutions on carbon and silica: Basic studies for the preparation of ecofriendly acidic catalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 251, 151–159 (2002).

Pizzio, L. R., Vázquez, P. G., Cáceres, C. V. & Blanco, M. N. Supported Keggin type heteropolycompounds for ecofriendly reactions. Appl. Catal. Gen. 256, 125–139 (2003).

Pe, E. & Soriano, E. Recent advances in the Friedländer reaction recent advances in the Friedländer reaction. Chem. Rev. 109, 2652–2671 (2009).

Khaligh, N. G., Mihankhah, T. & Johan, M. R. Synthesis of quinoline derivatives via the Friedländer annulation using a sulfonic acid functionalized liquid acid as dual solvent-catalyst. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 40, 1223–1237 (2020).

Acknowledgements

B.Krishna would like to thank Adama India Pvt Ltd for financial support. Both the authors acknowledge BITS Pilani Hyderabad Campus.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Birla Institute of Technology and Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. did the investigation, data curation, validation, and also wrote the original draft. S.R. conceptualizied the probelem, wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krishna, B., Roy, S. Promising metal-free green heterogeneous catalyst for quinoline synthesis using Brønsted acid functionalized g-C3N4. Sci Rep 14, 23686 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72980-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72980-1