Abstract

Poterium spinosum L. is a key plant species forming typical shrub communities, distributed across the Mediterranean eastern coasts. The conservation of P. spinosum is thus of the utmost importance, especially due to the ever-increasing environmental pressures like climate changes and habitat fragmentation. This study, in particular, investigated for the first time the germination variability of P. spinosum at intrapopulation level, by analysing the germination behavior of five different subpopulations growing along the coasts of Sicily. For a more exhaustive picture of the main drivers of biodiversity loss affecting the distributional area of P. spinosum, the trends of climate and land-cover changes were also studied over the periods 1931–2020 and 1958–2018, respectively. The results found significant intrapopulation variability in P. spinosum, whose germination parameters showed that fruits and seeds from distinct subpopulations respond differently to diverse temperatures. Seeds showed generally higher values of final germination percentage (FGP) compared to fruits, and at higher temperatures: the highest FGP in seeds was 70% at 20 °C, whereas in fruits was 58.2% at 15 °C. The environmental threats showed worrying trends across the study area: during 1931–2020, the average temperature increased by 1.5 °C, whereas the average rainfall declined from 710 to 650 mm. Similarly, in the period 1958–2018, the analysis of the CORINE land-cover changes showed a highly fragmented agricultural landscape, where natural areas were reduced to 2.5–5.0%. Germination variability at intrapopulation level should be considered as a fundamental adaptation strategy, which can increase the reproductive success of P. spinosum under climate and land-cover changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mediterranean Basin is one of the world’s major hotspots of plant biodiversity1,2,3, which, at the same time, faces a climate and habitat crisis due to ever-increasing warming, drying, deforestation and landscape fragmentation4,5,6,7. It is thus of the utmost urgency to assess the germination processes and the environmental threats that regard keystone plant species. One of these is the monospecific taxon Poterium spinosum L. (Rosaceae family), called “thorny burnet”, which dominates eastern Mediterranean shrublands known as “bathah” in Israel and “phrygana” in Greece8. Because of its severe fragmented distribution and scarce renewal capacity, P. spinosum is considered as “endangered” (EN) on a regional scale9, and as “vulnerable” (VU) on Italy’s scale10. Over the last few decades, massive landscape fragmentation further disrupted the range size of P. spinosum, causing local extinction and making surviving populations more and more scattered and isolated11,12.

Ex situ conservation of existing genetic resources is emerging as a valuable tool to create seed reserves for programs of biodiversity protection and restoration13. Regarding P. spinosum, several studies investigated its ecology and seed germination14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, to our knowledge, no study has ever investigated the germination behavior of P. spinosum at an intrapopulation level. In this study, indeed, we compared the different germination processes of five distinct subpopulations of P. spinosum, growing on the south-eastern coast of Sicily. Although analyzing intrapopulation variability of seed germination could improve our understanding of how plants adapt and survive, especially in unpredictable or changing environments, studies about intrapopulation germination are generally very poor21,22. For an exhaustive picture of the conservation state, germination studies should be also integrated with the investigation of environmental threats such as climate changes and habitat fragmentation, which are primary drivers of biodiversity loss23,24,25,26. The aims of this study were to investigate (a) the intrapopulation germination variability of P. spinosum at different temperatures, and (b) the trends of climate changes and (c) land-cover transformation affecting two different populations of P. spinosum over the periods 1931–2020 and 1958–2018, respectively. The ultimate end of this study was to corroborate the conservation efforts of P. spinosum by shedding further light on its germination ecology poorly known at intrapopulation level, and by providing a scenario that shows the magnitude of the threats posed by climate changes and habitat fragmentation.

Materials and methods

Study area

The distributional range of Poterium spinosum is restricted to the south-eastern part of Sicily, from Portopalo to Villasmundo localities (Fig. 1; Table 1). This area lies mainly on the Hyblean Plateau, which is crossed by numerous deep and narrow torrential canyons (in Italian, the so-called “cave”). Across the Hyblean Plateau, two distinct sectors can be recognized: the eastern sector mainly composed of a Cretaceous-Late Tortonian carbonate succession, with intercalations of vulcanites, and the western sector marked by an Oligocene–Miocene carbonate succession27,28. P. spinosum occurs along the coastline and in inner hilly areas (Fig. 1), both in protected areas (e.g., Natura 2000 sites) and in unprotected sites29,30,31. However, on the basis of direct field surveys, this species has almost disappeared from several localities such as “Costa Reitani” and “Marzamemi”. This study, in particular, analysed climate trends and land-cover changes affecting the populations of P. spinosum distributed across the coastal protected areas of “Plemmirio” (Fig. 1, site A) and “Vendicari” (Fig. 1, site B). The germination experiments focused instead on the subpopulations of P. poterium growing within the “Vendicari” reserve (Fig. 2). The “Plemmirio” area mainly consists of Pleistocene limestone rocks and calcarenites. In turn, the “Vendicari” area is characterized by rocks mixed with sandy dunes, which are inwards and often replaced by large brackish lagoons, such as the so called “Pantano Piccolo” (small quagmire) and “Pantano Grande” (large quagmire). The sedimentary sequence of the “Vendicari” site consists of Pliocene–Quaternary deposits. The climate of the distributional area of P. spinosum is typically Mediterranean, with irregular rainfall events, harsh dry summer (up to 5-month dry periods), and mild winter periods. According to the classification of Rivas-Martínez32, the study area lies in the Macrobioclimate Mediterranean, with thermo-mediterranean thermotype and semiarid ombrotype. The software ArcGIS version 10.2 was used to make Figs. 1 and 2, whose images are orthophotos publicly available from the official website of the Sicilian Regional Government.

Occurrence sites of Poterium spinosum across Sicily, and within the protected areas of “Plemmirio” (A) and “Vendicari” (B) (see Table 1 for the correspondence between number and site name).

Geographical distribution of subpopulations A, B, C, D, E of Poterium spinosum across the “Vendicari” protected area (site B as shown in Fig. 1).

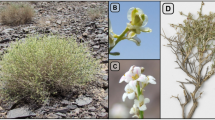

Biology and ecology of Poterium spinosum

The genus Poterium consists only of the species Poterium spinosum L., called “prickly burnet” or “thorny burnet”. Locally known as “spinaporci”, it is a nanophanerophyte belonging to the Rosaceae family (Fig. 3). P. spinosum is a very branchy thorny shrub (60–70 cm high, max 1 m), with young tomentose shoots; the lateral branches are leafless ending in dichotomous, whitish thorns; the leaves are imparipinnate and pubescent. Inflorescences (short spikes) with unisexual flowers are dense; the female flowers, with red–purple feathery stigmas, are in the upper portion, whereas the male flowers (with 10–30 stamens) are in the lower one16,33. Flowering season occurs from March to May, and fruits mature in the period June–August; the fruit is a spongy berry. P. spinosum reproduces by means of anemophily pollination, and autochory or endozoochory dispersal34. The annual fruit production is normally very high, but the rate of seed germination varies among different countries19. Although fire may promote germination and seed dispersal35,36, seedling survival is generally low37. The plant propagates both sexually and vegetatively. The vegetative reproduction occurs via rooting of branches (“ramets”); the production of new ramets can be thought of as growth leading to clonal expansion11.

P. spinosum is a pioneer species typical of shrublands known as “bathah” in Israel, “tomillares” in Spain, and “phrygana” in Greece8. In the eastern part of its distributional range, P. spinosum grows in a wide range of habitats38,39. The species shows a halo-tolerant trait interpreted as adaptation to coastal habitats where it generally grows19. In Italy this plant occurs in few regions33, and grows on a narrow range of habitats (garrigue/scrubland), in isolated and generally small zones near the shoreline, on calcareous rocks or on littoral gravelly areas31,40. In south-eastern Sicily, P. spinosum colonizes areas near the coastline as well as inner areas up to c. 600 m a.s.l., and usually grows on calcareous rocks and sandstones or sandy gravelly substrate.

Germination experiments

The laboratory tests investigated (1) the germination behavior of fruits and seeds of P. spinosum to shed further light on the effects of fruit spongy tissue on germinability; (2) how the germination behavior of P. spinosum varies at intrapopulation level. Regarding the second point, we compared, under four different conditions of temperature, several germination parameters of five different subpopulations of P. spinosum growing within a protected area (Fig. 2), which is also a Natura 2000 site (“Vendicari” ITA090002). To our knowledge, there are no studies that have ever investigated the germination variability of P. spinosum at intrapopulation level by using a comparative approach among subpopulations. Specifically, all fruits of P. spinosum were collected in July 2022 from five different subpopulations distributed across the study site “B” (“Vendicari” reserve, Fig. 2), along 8-km coastline at 0–30 m a.s.l. Large, robust and healthy subpopulations of P. spinosum were selected, with the highest density and quantity of reproductive output. P. spinosum is an evergreen dwarf shrub that dominates the “Vendicari” coastal garigue together with other species like Thymbra capitata, Cytisus infestus, Teucrium fruticans, Thymelaea irsuta, and Chamaerops humilis. In particular, P. spinosum garigue grows between Pistacia lentiscus and Juniperus macrocarpa scrubland, and rocky halophilous vegetation characterized by Limonium syracusanum.

The strategy for seed collection and post-harvest treatments followed the recommendations of national and international protocols41,42,43,44. Fruit clusters were collected, in each subpopulation, from 25–30 randomly chosen different plants of P. spinosum, 3–5 m far from each other to ensure that they were distinct individuals within a relatively large area (minimum 800 m2), thus obtaining an adequate representation of genetic diversity. Fruits were bulked into labelled paper bags and taken to the laboratory on the same day of the collection. After that, some fruits were pressed, and then a cutter was used to manually extract seeds; the other fruits were left untouched. The average mass of fruits and seeds (g ± SD) was calculated by weighing five replicates of 20 fruits and 20 seeds from each subpopulation (Table 2). The average weight (of 100 fruits and 100 seeds) was determined by using a balance with the accuracy of 0.001 g (Mettler AE 50). The dimensions (length and width) of ten random fruits and seeds were measured through a stereoscopic microscope (Olympus SZX 12 stereo microscope). Regarding the kind of embryo, on the basis of Martin’s46 key for the types of seeds47, the embryo may be considered as spatulate fully developed.

Germination tests were performed in the laboratories of the Germplasm Bank (BGS-CT) of the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences, Catania University. The following pretreatments and experiments were carried out according to the germination tests of the plant species Muscari gussonei45. Before starting the germination tests, all fruits and seeds were cleaned and stored at controlled conditions (20 °C, 40% relative humidity) for about two weeks before use; fruits and seeds that were not used in the germination tests were stored at −18/−20 °C for long-term ex situ conservation; fruits and seeds, used in the experiments, were preliminarily washed with sterile distilled water. All germination tests were carried out in growth chambers under controlled temperature and light conditions; the light in each growth chamber was provided by white fluorescent tubes (Osram FL 40 SS W/37), with photosynthetic photon flux density of 40 μmol m-2 s-1. These experiments considered various temperature regimes, including three fixed (10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C) and one alternating (10/20 °C) temperatures, and a photoperiod of 12-h light and 12-h dark (12/12 h light–dark); for each experimental condition and for each of the five subpopulations, four replicates of 25 fruits and of 25 seeds were sown on three layers of filter papers, moistened with distilled water in plastic Petri dishes, 9 cm in diameter. Distilled water was added as needed, and parafilm M® was used for wrapping (sealing) the Petri dishes to limit any moisture loss, and reduce contamination. Fruit/seed germination was checked daily, and the criterion to establish germination was the emergence of a 1-mm long radicle43. The experiments were considered finished after 60 days since the start of the germination tests. At the end of the incubation period, the viability of each remaining fruit/seed was estimated by the cut test, and each fruit/seed was classified as viable/fresh, empty or dead 44. Fruit/seed with white and firm embryos were considered viable; empty and deteriorated (dead) fruits/seeds were excluded from the calculation of the final germination percentages (FGP); viable fruits/seeds, which did not germinate at the end of each test, were not further investigated.

Germination parameters

The following parameters were used to investigate the germination process of P. spinosum:

(a) Final germination percentage (FGP)48,

where

ni = number of seeds germinated on the ith day;

k = 60, number of days of experiment duration;

N = 25, total number of seeds put in a Petri dish;

(b) Mean germination time (MGT)49,

where

ti = number of days between the start of the experiment and the ith day;

(c) Mean germination rate (MGR), calculated as the reciprocal of MGT50,

(d) First day of germination (FDG), expressed as the day on which the first germination event occurs51;

(e) Last day of germination (LDG), expressed as the day on which the last germination event occurs51;

(f) Median germination time (T50)52,

where

N = final number of germinated seeds;

ni and nj are the total number of seeds germinated by adjacent counts at time ti and tj , with ni < N/2 < nj;

(g) Coefficient of variation of the mean germination time (CVt)50,

where the variance of the mean germination time is expressed as:

(h) Coefficient of velocity of germination (CVG)53,

Germination rate index (GR)54,

where G1 is the final germination percentage (FGP1) on day 1, G2 is the final germination percentage (FGP2) on day 2, and so on;

(j) Germination index (GI)55,

where n1, n2,…, n60, are respectively the number of seeds germinated on the first, second,…ith day.

Climate patterns: multi-temporal analysis

Air temperature and rainfall are key parameters to describe climate, which is one of the main elements used to define plant niches and species distribution56,57. In particular, this study investigated the multi-temporal trends of temperature and rainfall in the two protected areas examined. Climate analysis followed the methodology of Bonanno and Veneziano45. The climate oscillations of these areas were analysed over a 90-year period, by considering three 30-year time intervals, namely 1931–1960, 1961–1990, 1991–2020, and the whole investigated period of 90 years (1931–2020) (Figs. 4, 5). The raw data used for the processing were recorded by the weather stations located in the towns and villages near the two protected areas. Such data were obtained from the official website of the Sicilian Regional Government58. In particular, a total of 20 weather stations was selected within a radius of 30 km from the sites “Plemmirio” (site A) and “Vendicari” (site B). Each annual mean value of temperature and rainfall—shown in Figs. 4, 5—was obtained through the kriging interpolation of the annual mean values of the selected weather stations. The annual mean values of the weather stations were first arranged in an excel spreadsheet, and then processed with the software ArcGIS version 10.2.

CORINE Land Cover: multi-temporal analysis

The CORINE Land Cover (CLC) methodology was applied to investigate the multi-temporal variations of soil-use across the two study areas where P. spinosum is mainly distributed45. CLC III level was specifically used to determine land-cover classes in 1990, 2000, 2006, 2012, 2018 (Figs. 6, 7). The CLC GIS data were provided by SINANET59. As regards land-cover data in 1958, the information was collected from the “map of Italy’s soil-use”60. The correspondence between CNR-TCI classes and CLC classes was shown in Figs. 6, 7. All soil-use data were preliminarily transformed into shapefiles, and then processed through the software ArcGIS version 10.2.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used when two related samples were compared. In case of unrelated pairs of samples, the Mann–Whitney U-test was carried out. The Friedman test was instead used when the comparison of multiple related samples was needed. The Kruskal–Wallis H-test was carried out when multiple unrelated samples were compared. To detect significant differences between pairs, contrasts were carried out with the Wilcoxon signed ranks test (related pairs) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (unrelated pairs). We specifically used Kruskal–Wallis H-test and Mann–Whitney U-test to check whether each morphometric parameter of P. spinosum (seeds and fruits) varied significantly among the five studied subpopulations (Table 2). These same tests were also used to verify whether each germination parameter, at the same temperature conditions, was statistically different among the five subpopulations of P. spinosum (Tables 3 and 4). The Friedman test and the Wilcoxon signed ranks test were instead carried out to ascertain whether each germination parameter changed significantly under different temperature conditions and within the same subpopulation (Tables 3 and 4). Similarly, we conducted Friedman and Wilcoxon tests to show whether each CORINE Land Cover class varied significantly over different time intervals (Table 5). Conducting multiple contrasts may increase the Type I error rate. The initial level of risk (α = 0.05) was therefore adapted according to the Bonferroni formula αB = α/k, where αB is the adapted level of risk, and k is the number of comparisons45. The Kendall rank correlation coefficient was applied to check for significant monotonic correlations. The degree of significance was set at 0.05. Statistical processing was performed with the statistical package IBM SPSS Version 27.0.

Results and discussion

Germination response of Poterium spinosum

The germination parameters of P. spinosum showed a general pattern according to which fruits and seeds from distinct subpopulations (subpops) respond differently to diverse temperatures (Tables 3, 4). Specifically, the highest values of FGP were found at 15 °C for the fruits of subpops A, C, D, E, whereas the fruits of subpop B reported their greatest FGP at 10 °C. In turn, the seeds of subpops B, C, D, E reached the highest FGP at 20 °C, except for subpop A, which did so at 15 °C. Seeds showed generally higher values of FGP compared to fruits, and at higher temperatures, namely 20 °C in seeds versus 15 °C in fruits. In particular, the highest FGP in seeds was 70% (subpop C at 20 °C), whereas FGP = 58.2% was the highest value in fruits (subpop C at 15 °C). The results of the other germination parameters further corroborated the significant intrapopulation variability of P. spinosum. For instance, the lowest mean values of MGT in fruits were found in subpops A (10 days) and C (15.9) at 20° C, B at 10/20 °C (12.7), D at 10 °C (16.3), and E at 15 °C (17.4). In seeds, the trend of MGT was (lowest mean values): 14.4 days in subpop A, 12.3 in B and 13 in C at 15 °C, and 14.3 in D and 14.1 in E at 20 °C. Similarly, T50 showed significant variability in fruits and seeds among distinct subpopulations at different temperatures. In particular, the lowest mean values of T50 in fruits were 11 days in subpop A, 12 in C, 13.5 in D and 16 in E at 15 °C, whereas 13.5 days in subpop B at 10/20 °C. In seeds, the lowest mean values of T50 were instead 9.8 days in subpop A at 15 °C, 11.2 in B, 10.5 in C and 11.5 in E at 20 °C, as well as 12.8 days in subpop D at 10/20 °C.

This study showed that the optimum germination temperatures of P. spinosum are mainly in the range of 15–20 °C, in general agreement with previous authors. Santo et al.19 found that P. spinosum seeds reach the highest FGP in the range of 10–20 °C, in different populations from several Mediterranean countries. Similarly, Meloni61 found that 20 °C is the most favorable temperature for P. spinosum germination in populations from Sardinia, Greece and Malta. Lantieri et al.18 investigated instead populations from Sicily, and identified the range of 15–20 °C as the optimum condition for germination. The results of this study corroborated previous research according to which P. spinosum shows the “Mediterranean germination syndrome” that is typical of Mediterranean coastal species62,63, whose germination occurs at low and moderate temperatures (10–20 °C). All these findings suggest that the field germination of P. spinosum is especially favored between autumn and early spring62,64, when the higher water availability may further stimulate seed germination. This study, in particular, showed that germination optimum temperatures are different, namely 15 °C in fruits and 20 °C in seeds. Moreover, seeds showed higher values of germinability compared to fruits (seeds+spongy tissues). These results suggest that spongy tissues may reduce both temperature optimum and germinability. Vahl14 noted that seeds stripped of fruit spongy tissues germinated faster and with greater percentages, suggesting the presence of an inhibitor in the spongy material. Similarly,16 detected a slower germination time in fruits than seeds. Santo et al.19, however, found that the influence of spongy tissues may vary among different populations: for some of them it caused a remarkable reduction in germinating seeds, but for others the effects were not significant. Further light should be shed on the possible presence of an inhibitor in the spongy tissue of P. spinosum fruits, and the associated effects.

Previous studies found a great germination variability at interpopulation level in P. spinosum, thus suggesting that Mediterranean populations of P. spinosum are considerably different among them and highly adapted to local habitat conditions19,61. Latitude, altitude, temperature, rainfall, light, moisture, soil nutrients, proximity to the sea and habitat disturbance are among the numerous factors linked to interpopulation variability of germination 47. This study, however, found that P. spinosum can show significantly different germination patterns also within the same population. If, on the one hand, different abiotic conditions may explain different germinability among populations of P. spinosum from ecologically diverse Mediterranean regions, on the other hand, as shown in this study, a different germination behavior can be also found among subpopulations of P. spinosum distributed along a narrow coastal strip, environmentally homogeneous. The significant germination variability at subpopulation level of this Sicilian population (“Vendicari”, site B) may be associated with the peripheral position of Sicily in the western geographical distribution of P. spinosum. Peripheral populations are usually influenced by evolutionary divergence processes31, which could differentiate them not only from other populations but also within the same population. In particular, several factors such as maternal reproductive phenology and microenvironment, as well as genotype, can be responsible for the variation of germination response among individuals of the same population65,66,67. Germination variability may also exist at intrapopulation level as a bet-hedging strategy for enabling the species to produce numerous seeds optimized for different climatic conditions68. As a result, this intrapopulation variation increases the probability of generational survival in an unpredictable or changing environment21,69. High intrapopulation variability can be thus considered as an adaptation strategy that can increase the reproductive success of P. spinosum under climate and land-use changes. The results of this study shed further light on P. spinosum seed ecology, and therefore contributed to develop new germination protocols than can be used for conservation and restoration programs across a global climate and biodiversity hotspot: the Mediterranean region.

Multi-temporal trends of temperature and rainfall in the study areas of P. spinosum

Climate patterns reported rising temperature and declining rainfall over a 90-year period in site A (Plemmirio reserve) and site B (Vendicari reserve) (Figs. 4 and 5). The values of temperature and rainfall, in particular, showed oscillating values over the three 30-year subperiods. Regarding temperature, in the period 1931–1960, the average values were relatively constant, within the range of 17.1–17.2 °C, whereas in the following period of 1961–1990, the average temperature increased significantly by 0.9 °C (17–17.9 °C). Over the last interval of 1991–2020, the average values declined moderately by 0.3 °C (18.3–18 °C). Overall, in the whole period of 1931–2020, the average temperature increased significantly by 1.5 °C, specifically from 16.8 to 18.3 °C. Regarding rainfall, the oscillations were instead more moderate. In the first period of 1931–1960, the average values ranged from 710 to 790 mm, marking a significant increase of 80 mm. However, in the following two 30-year periods, rainfall showed declining trends: during 1961–1990, the average values decreased from 620 to 580 mm, whereas during 1991–2020, from 700 to 690 mm. In the whole 90-year study period, from 1931–2020, the average rainfall decreased from 710 to 650 mm.

Climate change is already impacting biodiversity and is likely to intensify over the next few decades unless practical mitigation efforts are implemented70. The Mediterranean region, in particular, is not only a hotspot of climate changes7, but also a hotspot of biodiversity, characterized by an endemic flora expected to experience severe global warming71,72. Rising temperatures and declining rainfall can indeed seriously compromise the germinability of most Mediterranean species, especially those with a narrow germination optimum such as P. spinosum, whose best conditions for germination are moderate temperatures at 15–20 °C. In this study, no mitigation trends were found for the climate conditions affecting P. spinosum range, where temperature increase by 1.5 °C during 1931–2020 is equivalent to 0.17 °C/decade, in line with current global warming increase at about 0.2 °C/decade73. According to IPCC70, during 2016–2035, the average global temperature is expected to increase between 0.3 and 0.7 °C, and global warming is likely to reach 1.5 °C between 2030 and 2052. Similarly to this study, in most areas of the Mediterranean region, precipitation is predicted to decrease (− 12%), particularly in summer (− 24%) 74.

Concerns associated with variations in global temperature, rainfall and other climate variables encouraged research addressing the impact of climate changes on species distribution57,75,76. Geographic range shifts, expansions and contractions are indeed some of the main responses of species to climate changes77. In particular, species with wide geographic ranges are expected to be theoretically less vulnerable, as they may find refugia within their distributional area77. However, extreme variability in annual and seasonal patterns of temperature and precipitation can disrupt a wide range of natural processes, especially when changes occur more quickly than species adaptation56,70. As a result, the peculiarities of Mediterranean climate may restrict plant adaptive plasticity. Mediterranean climate can indeed be highly unpredictable, and this can reduce plasticity if environmental signals that trigger adaptive responses are unstable, or maintaining induced phenotypes proves biologically expensive under changeable climatic conditions78,79,80. However, this study found significant differences in the germination behavior of five subpopulations of P. spinosum, thus suggesting both significant within-population genetic diversity, and potential plasticity not only at interpopulation but also at intrapopulation level. Various studies found evidence for significant within-population evolutionary potential for functionally important traits in several Mediterranean species81,82. A highly different germination behavior at intrapopulation level, as found in this study for P. spinosum, may be taken as evidence for the existence of the underlying genetic variation necessary for an effective response to strong selection pressures imposed by climate changes.

Despite the consequences for species survival under global changes83,84, overall, the level of adaptive plasticity and evolutionary potential is poorly known in Mediterranean plants85,86. In particular, the rate at which environmental conditions change can also constrain adaptive evolution if species are not able to track changes, despite the presence of genetic variation84,87. Long-term demographic surveys are also needed to understand how past climatic variations affected population dynamics, and to predict population viability under climate changes88,89,90. Further studies are thus necessary to shed light on how patterns of plasticity vary among and within populations for different traits and ecological factors, and whether current eco-physiological processes will still be adaptive under future environmental conditions.

Land-cover multi-temporal trends in the study areas of P. spinosum

CORINE land-cover (CLC) classes, 3rd level, were reported for the period 1958–2018, in the study areas of “Plemmirio” (site A) and “Vendicari” (site B) (Figs. 6, 7; Table 5). In site A, artificial areas ranged between 18.7% in 1990–2000, and 21.2% in 2012–2018, whereas site B showed a much lower artificial surface, which was only 1.3% in 1990–2000, and 2.0% in 2018. The “discontinuous urban fabric” (1.1.2.) was the dominant CLC class in site A, and the only one in site B. Both site A and site B showed instead a complex and variegated soil-use mosaic mainly characterized by several agricultural classes. Specifically, the total agricultural surface of site A was 93.9% in 1958, and then declined progressively until the stable value of c. 76% during 2012–2018. Similarly, site B showed a very high agricultural surface, which was 98.3% in 1958, and then stabilized at c. 91% in the period 2012–2018. The dominant agricultural classes were “non-irrigated arable land” (class 2.1.1.) and “fruit trees and berry plantations” (class 2.2.2.) in sites A and B, the latter of which was also characterized by “annual crops associated with permanent crops” (class 2.4.1.). Regarding forests and semi-natural areas, although site A showed an appreciable value of 7.7% in the decade 1990–2000, this figure dramatically declined to 2.5% in the period 2012–2018. The trend of site B was similar, with an initial value of 7.3% during 1990–2000, and a final surface of 5.1% in 2012–2018. Sclerophyllous vegetation was the main natural area in both study sites (class 3.2.3.). Overall, salt marshes (4.2.1.) and coastal lagoons (5.2.1.) were negligible respectively in site A (0.5%) and site B (1.9%).

Land-cover transformation as a result of agricultural expansion is one of the most serious drivers of loss and fragmentation of natural habitats, with consequent strong decline in biodiversity91,92,93. Agricultural expansion may especially cause the fragmentation of agricultural landscapes, which become complex, heterogeneous and discontinuous94. Agricultural landscape fragmentation affects biodiversity by impacting on the distribution, migration and movement of species95,96. In particular, by disrupting pollination and diaspore dispersal processes, landscape fragmentation increases genetic drift and inbreeding, thus reducing genetic diversity within plant populations97,98. The consequences of habitat fragmentation for Mediterranean plants are many. Firstly, fragmentation can decrease individual plant fitness and increase population extinction risk due to environmental and demographic stochasticity99,100,101. Secondly, fragmentation can inhibit plant migration if suitable habitat patches are not sufficiently connected to allow gene flow via pollen and seeds102. Thirdly, habitat fragmentation can have interactive and indirect effects on the adaptive potential of plants to other global transformation drivers such as climate changes103,104. This study, in particular, showed that, in Sicily, P. spinosum has a fragmented distribution globally and locally (Figs. 1, 2). This scattered range of P. spinosum may not only reduce genetic variation for fitness-related traits, but also reduce genetic variation for plasticity. Although this hypothesis has been poorly investigated for Mediterranean plants105, the significantly different germination behavior of P. spinosum at subpopulation level suggests that this plant may keep a certain level of plasticity within populations distributed across highly fragmented and impacted agricultural landscapes. Future studies, however, are needed to shed further light on genetic variation and plasticity in P. spinosum along fragmentation gradients, and how these traits can influence the response of Mediterranean plants to climate and land-cover changes.

Landscape changes often lead to habitat fragmentation, affecting both structure and function through loss of original habitat, reduction in habitat patch size, and increasing isolation of patches106,107. Habitat fragmentation is consequently a key conservation concern in many countries, and is strongly associated with loss of biodiversity108,109. In particular, the scattered layout of landscape patches affects the connectivity of the landscape itself, hinders the interaction between different patches, and cause degradation in the quality of natural habitats110. Ecological networks are increasingly accepted as proactive tools for preserving biodiversity by improving landscape connectivity111,112. Conservation on a landscape scale is especially recommended when the populations of a species are highly fragmented across a vast territory such as P. spinosum, whose populations are scattered across south-east Sicily (Fig. 1). Increasing landscape connectivity should be therefore considered as one of the main guiding principles to re-establish the genetic connections within the P. spinosum metapopulation in Sicily.

Conclusions

The highly different germination behavior of P. spinosum at subpopulation level suggests that this species may be characterized by a significant intrapopulation genetic variability. Although this trait is poorly known for Mediterranean plants, it is undeniable that this possible genetic resilience of P. spinosum is encouraging in the face of the ongoing severe climate and land-cover changes. However, the distribution ranges of P. spinosum are generally scattered both locally and across the Mediterranean region. To support genetic fluxes at interpopulation level, at least on a landscape scale, conservation measures should aim to increase the ecological connectivity among highly fragmented natural habitats. P. spinosum communities—the so called “phrygana” or thorny garigue—are distinctive features of Mediterranean landscapes. As a result, their protection and restoration should be a priority for any organization in charge of biodiversity conservation. The germination tests of this study may also contribute to the conservation of P. spinosum. These lab experiments showed indeed that fruits and seeds of P. spinosum not only show different germination optimum but also different germinability. This different germination behavior of fruits and seeds should be considered as an important starting point for any conservation program of P. spinosum, both in situ and ex situ.

Plant materials statement

The permission to collect specimens of Poterium spinosum was granted by the Regional Government of Sicily, which is the managing body of the “Vendicari” Natural Reserve. Plant collection and use were in accordance with all the relevant guidelines. Specifically, in compliance with the collection permission, all specimens of P. spinosum were < 10% of the sampled populations. Voucher specimens were deposited in the public herbarium of the Botanical Garden of Catania University (Italy). Specimens were collected, identified and deposited by the authors of this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences (Catania University, Italy).

References

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions (University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Thompson, J. D., Lavergne, S., Affre, L., Gaudeul, M. & Debussche, M. Ecological differentiation of Mediterranean endemic plants. Taxon 54, 967–976 (2005).

Alados, C. L. et al. Variations in landscape patterns and vegetation cover between 1957 and 1994 in a semiarid Mediterranean ecosystem. Landsc. Ecol. 19, 543–559 (2004).

Blondel, J., Aronson, J., Bodiou, J.-Y. & Boeuf, G. The Mediterranean Region: Biological Diversity through Time and Space 2nd edn. (Oxford University Press, 2010).

AllEnvi. The Mediterranean Region under Climate Change (IRD Editions, 2016).

Ducrocq, V. Climate change in the Mediterranean region. In The Mediterranean Region Under Climate Change 71 (IRD Editions, 2016).

Evenari, M. et al. (eds) Ecosystems of the World: Hot Deserts and Arid Shrublands (Elsevier Science Publishers, 1986).

IUCN. IUCN Red List categories and criteria: version 3.1. Gland, Cambridge: IUCN Species Survival Commission. (2001).

Conti, F., Manzi, A. & Pedrotti, E. Liste Rosse Regionali delle Piante dItalia 139 (WWF Italia, Società Botanica Italiana, CIAS, Univ., 1997).

Seligman, N. & Henkin, Z. Persistence in Sarcopoterium spinosum dwarf-shrub communities. Plant Ecol. 164, 95–107 (2002).

Caruso, G. Una nuova stazione di Sarcopoterium spinosum (Rosaceae) nellʹItalia peninsulare. Inform. Bot. Ital. 45(2), 221–226 (2013).

Haidet, M. & Olwell, P. Seeds of success: A national seed banking program working to achieve long-term conservation goals. Nat. Areas J. 35(1), 165–173 (2015).

Vahl, I. On germination inhibitors. III. Germination inhibitors in the fruit of Poterium spinosum L.. Palest. J. Bot. Jerus. Ser. 2, 28–32 (1940).

Litav, M., Kupernik, G. & Orshan, G. The role of competition as a factor in determining the distribution of dwarf shrub communities in the Mediterranean Territory of Israel. J. Ecol. 51(2), 467–480 (1963).

Litav, M. & Orshan, G. Biological flora of Israel: Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Sp.. Isr. J. Bot. 20, 48–64 (1971).

Roy, J. & Arianoutsou-Faraggitaki, M. Light quality as the environmental trigger for the germination of the fire-promoted species Sarcopoterium spinosum L.. Flora 177, 345–349 (1985).

Lantieri, A., Guglielmo, A., Pavone, P. & Salmeri, C. Seed germination in Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Spach from south-eastern Sicily. Plant Biosyst. 147, 60–63 (2013).

Santo, A. et al. Seed germination ecology and salt stress response in eight Mediterranean populations of Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Spach. Plant Species Biol. 34, 110–121 (2019).

Waitz, Y. et al. Close association between flowering time and aridity gradient for Sarcopoterium spinosum in Israel. J. Arid Environ. 188, 104468 (2021).

Zhao, N. X. et al. Trait differentiation among Stipa krylovii populations in the inner Mongolia Steppe region. Flora 223, 90–98 (2016).

Bhatt, A., Gallacher, D. J., Jarma-Orozco, A. & Pompelli, M. F. Seed mass, dormancy and germinability variation among maternal plants of four Arabian halophytes. Seed Sci. Res. 32, 53–61 (2022).

Tscharntke, T., Klein, A. M., Kruess, A., Steffan-Dewenter, I. & Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity—Ecosystem management. Ecol. Lett. 8, 857–874 (2005).

Selwood, K. E., McGeoch, M. A. & Mac Nally, R. The effects of climate change and land-use change on demographic rates and population viability. Biol. Rev. 90, 837–853 (2015).

Wiens, J. J. Climate-related local extinctions are already widespread among plant and animal species. PLoS Biol. 14, e2001104 (2016).

Song, X.-P. et al. Global land change from 1982 to 2016. Nature 560, 639–643 (2018).

Grasso, M. & Lentini, F. Sedimentary and tectonic evolution of the eastern Hyblean Plateau (southeastern Sicily) during late Cretaceous to Quaternary time. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 39(3–4), 261–280 (1982).

Pedley, H. M., Cugno, G. & Grasso, M. Gravity slide and resedimentation processes in a Miocene carbonate ramp, Hyblean Platcau, southeastern Sicily. Sediment. Geol. 79(1–4), 189–202 (1992).

Barbagallo, C., Brullo, S. & Fagotto, F. Boschi Di Quercus Ilex L. Del Territorio Di Siracusa e Principali Aspetti Di Degradazione 28 (Istituto di botanica dell’Università di Catania, 1979).

Bartolo, G., Brullo, S., Minissale, P. & Spampinato, G. Osservazioni fitosociologiche sulle pinete a Pinus halepensis Miller del bacino del fiume Tellaro (Sicilia Sud-Orientale). Boll. Acc. Gioenia Sci. Nat. 18, 255–270 (1985).

Gargano, D., Fenu, G., Medagli, P., Sciandrello, S. & Bernardo, L. The status of Sarcopoterium spinosum (Rosaceae) at the western periphery of its range: Ecological constraints lead to conservation concerns. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 55, 1–13 (2007).

Rivas-Martínez, S. Global bioclimatics. In Clasificación Bioclimática de la Tierra (Phytosociological Research Center, 2004).

Pignatti, S. Flora dItalia (Edagricole, 1982).

Pignatti, S. Flora dItalia 2nd edn, 1214 (Edagricole Calderini, 2017).

Naveh, Z. Agro-Ecological Aspects of Brush Range Improvement in the Maquis Belt of Israel (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1959).

Baskin, C. C. & Baskin, J. M. Seeds: Ecology, biogeography and evolution of dormancy and germination (Academic Press, 1998).

Henkin, Z., Seligman, N. G., Noy-Meir, I. & Kafkafi, U. Secondary succession after fire in a Mediterranean dwarf-shrub community. J. Veg. Sci. 10, 503–514 (1999).

Eig, A. Synopsis of the phytogeographical units of Palestine. Palest. J. Bot. 3, 183–246 (1946).

Zohary, M. Geobotanical foundations of the Middle East (Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1973).

Biondi, E. & Mossa, L. Studio fitosociologico del promontorio di Capo S. Elia e dei colli di Cagliari (Sardegna). Doc. Phytosoc. 14, 1–44 (1992).

Bacchetta G, Fenu G, Mattana E, Piotto B, Virevaire M Manuale per la raccolta, studio, conservazione e gestione ex situ del germoplasma. Manuali e Linee Guida APAT 37/2006, APAT, Roma. (2006).

Bacchetta G, Fenu G, Mattana E, Piotto B. Procedure per il campionamento in situ e la conservazione ex situ del germoplasma. Manuali e linee guida ISPRA, 118/2014. (2014).

ENSCONET. Germination Recommendations. Updated. (2009).

ISTA. International rules for seed testing 2017. The International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). Bassersdorf, Switzerland. (2017).

Bonanno, G. & Veneziano, V. Rise, fall and hope for the Sicilian endemic plant Muscari gussonei: A story of survival in the face of narrow germination optimum, climate changes, desertification and habitat fragmentation. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169208 (2024).

Martin, A. C. The comparative internal morphology of seeds. Am. Midl. Nat. 36, 513–660 (1946).

Baskin, C. C. & Baskin, J. M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination 2nd edn. (Academic Press, 2014).

Scott, S., Jones, R. & Williams, W. Review of data analysis methods for seed germination. Crop Sci. 24, 1192–1199 (1984).

Orchard, T. Estimating the parameters of plant seedling emergence. Seed Sci. Tech. 5, 61–69 (1977).

Khan, S. et al. Quantifying temperature and osmotic stress impact on seed germination rate and seedling growth of Eruca sativa Mill. via hydrothermal time model. Life 12(3), 400 (2022).

Al-Mudaris, M. A. Notes on various parameters recording the speed of seed germination. J. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 99, 147–154 (1998).

Coolbear, P., Francis, A. & Grieson, D. The effect of low temperature pre-sowing treatment on the germination performance and membrane integrity of artificially aged tomato seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 35(160), 1609–1617 (1984).

Jones, K. & Sanders, D. The influence of soaking pepper seed in water or potassium salt solutions on germination at three temperatures. J. Seed Tech. 11, 97–102 (1987).

Esechie, H. Interaction of salinity and temperature on the germination of Sorghum. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 172, 194–199 (1994).

Benech Arnold, R. L., Fenner, M. & Edwards, P. J. Changes in germinability, ABA content and ABA embryonic sensitivity in developing seeds of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. induced by water stress during grain filling. New Phytol. 118, 339–347 (1991).

Kaky, E. & Gilbert, F. Predicting the distributions of Egypt’s medicinal plants and their potential shifts under future climate change. PLoS One 12, 1–19 (2017).

Ferrarini, A., Dai, J., Bai, Y. & Alatalo, J. M. Redefining the climate niche of plant species: A novel approach for realistic predictions of species distribution under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 671, 1086–1093 (2019).

Sicilian Regional Government. Meteorological records. https://www.regione.sicilia.it/istituzioni/regione/strutture-regionali/presidenza-regione/autorita-bacino-distretto-idrografico-sicilia/annali-idrologici. (2022).

SINANET. CORINE Land Cover. https://groupware.sinanet.isprambiente.it/uso-copertura-e-consumo-di-suolo/library/copertura-del-suolo/corine-land-cover. (2018).

CNR-TCI. Carta dellʹutilizzazione del suolo. Foglio n. 23. Touring Club Italiano. (1958).

Meloni F. Climate change impact on Mediterranean flora: Biological-reproductive study of vulnerable species. Tesi di Dottorato in Botanica ambientale ed applicata. Capitolo, Italy: Università degli Studi di Cagliari, 4: 73-85. (2010).

Thanos, C. A., Kadis, C. C. & Skarou, F. Ecophysiology of germination in the aromatic plants thyme, savory and oregano. Seed Sc. Res. 5, 161–170 (1995).

Kadis, C. & Georghiou, K. Seed dispersal and germination behavior of three threatened endemic labiates of Cyprus. Plant Species Biol. 25, 77–84 (2010).

Thanos, C. A., Georghiou, K., Douma, D. J. & Marangaki, C. J. Photoinhibition of seed germination in Mediterranean maritime plants. Ann. Bot. 68, 469–475 (1991).

Baloch, H. A., Di Tommaso, A. & Watson, A. K. Intrapopulation variation in Abutilon theophrasti seed mass and its relationship to seed germinability. Seed Sci. Res. 11, 335–343 (2001).

Galloway, L. F. The effect of maternal phenology on offspring characters in the herbaceous plant Campanula americana. J. Ecol. 90, 851–858 (2002).

Donohue, K. et al. Environmental and genetic influences on the germination of Arabidopsis thaliana in the field. Evolution 59, 740–757 (2005).

Mitchell, J., Johnston, I. G. & Bassel, G. W. Variability in seeds: Biological, ecological, and agricultural implications. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 809–817 (2017).

Slatkin, M. Competition and regional coexistence. Ecology 55, 128–134 (1974).

IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte, V., et al. (Eds.), Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1–32. (2018).

Beaumont, L. J., Pitman, A., Perkins, S. & Thuiller, W. Impacts of climate change on the world’s most exceptional ecoregions. PNAS 108(6), 2306–2311 (2011).

Bellard, C., Bertelsmeier, C., Leadley, P., Thuiller, W. & Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 15(4), 365–377 (2012).

Yobom, O. Climate change and variability: Empirical evidence for countries and agroecological zones of the Sahel. Clim. Change 159, 365–384 (2020).

Christensen, J. H. et al. Regional climate projections. In Climate Change, 2007: The Physical Science Basis 848–940 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Araujo, M., Pearson, R., Thuiller, W. & Erhard, M. Validation of species-climate impact models under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 1504–1513 (2005).

Márquez, A. L., Real, R., Olivero, J. & Estrada, A. Combining climate with other influential factors for modelling the impact of climate change on species distribution. Clim. Change 108, 135–157 (2011).

Thompson, J. D. Plant evolution in the Mediterranean. In Insights for Conservation 2nd edn (Oxford University Press, 2020).

DeWitt, T. J., Sih, A. & Wilson, D. S. Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 77–81 (1998).

Pigliucci, M. Phenotypic Plasticity: Beyond Nature and Nurture (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Sánchez-Gómez, D., Zavala, M. A. & Valladares, F. Functional traits and plasticity linked to seedlings’ performance under shade and drought in Mediterranean woody species. Ann. For. Sci. 65, 311 (2008).

Sixto, H., Salvia, J., Barrio, M., Ciria, M. P. & Canellas, I. Genetic variation and genotype-environment interactions in short rotation Populus plantations in southern Europe. New For. 42, 163–177 (2011).

Grivet, D. et al. Adaptive evolution of Mediterranean pines. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68, 555–566 (2013).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgrò, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (2011).

Shaw, R. G. & Etterson, J. R. Rapid climate change and the rate of adaptation: Insight from experimental quantitative genetics. New Phytol. 195, 752–765 (2012).

de Luis, M. et al. Cambial activity, wood formation and sapling survival of Pinus halepensis exposed to different irrigation regimes. For. Ecol. Manag. 262, 1630–1638 (2011).

Sánchez-Gómez, D. et al. Inter-clonal variation in functional traits in response to drought for a genetically homogeneous Mediterranean conifer. Environ. Exp. Bot. 70, 104–109 (2011).

Valladares, F. A mechanistic view of the capacity of forest to cope with climate change. In Managing Forest Ecosystems: the Challenge of Climate Change (eds Bravo, F. et al.) (Springer Verlag, 2008).

Zeigler, S. Predicting responses to climate change requires all life-history stages. J. Anim. Ecol. 82, 3–5 (2013).

Huelber, K. et al. Uncertainty in predicting range dynamics of endemic alpine plants under climate warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 2608–2619 (2016).

Franklin, J., Serra-Diaz, J. M., Syphard, A. D. & Regan, H. M. Big data for forecasting the impacts of global change on plant communities. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 6–17 (2017).

Sala, O. E. et al. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287, 1770–1774 (2000).

Williams, D. R. et al. Proactive conservation to prevent habitat losses to agricultural expansion. Nat. Sustain. 4, 314–322 (2021).

Potapov, P. et al. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 3, 19–28 (2022).

Yu, Q., Hu, Q., van Vliet, J., Verburg, P. H. & Wu, W. GlobeLand30 shows little cropland area loss but greater fragmentation in China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 66, 37–45 (2018).

Verhagen, W. et al. Effects of landscape configuration on mapping ecosystem service capacity: A review of evidence and a case study in Scotland. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 1457–1479 (2016).

Dener, E. et al. Direct and indirect effects of fragmentation on seed dispersal traits in a fragmented agricultural landscape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 309, 107273 (2021).

Honnay, O. & Jacquemyn, H. Susceptibility of common and rare plant species to the genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation. Conserv. Biol. 21(3), 823–831 (2007).

Aguilar, R., Quesada, M., Ashworth, L., Herrerias-Diego, Y. & Lobo, J. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in plant populations: Susceptible signals in plant traits and methodological approaches. Mol. Ecol. 17(24), 5177–5188 (2008).

Matesanz, S., Escudero, A. & Valladares, F. Impact of three global change drivers on a Mediterranean shrub. Ecology 90, 2609–2621 (2009).

Gonzalez-Varo, J. P., Albaladejo, R. G., Aparicio, A. & Arroyo, J. Linking genetic diversity, mating patterns and progeny performance in fragmented populations of a Mediterranean shrub. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 1242–1252 (2010).

Pias, B. et al. Transgenerational effects of three global change drivers on an endemic Mediterranean plant. Oikos 119, 1435–1444 (2010).

Leimu, R., Vergeer, P., Angeloni, F. & Ouborg, N. J. Habitat fragmentation, climate change, and inbreeding in plants. In Year in Ecology and Conservation Biology (eds Ostfeld, R. S. & Schlesinger, W. H.) 84–98 (Wiley, 2010).

Ortego, J., Bonal, R. & Munoz, A. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in long-lived tree species: The case of the Mediterranean Holm Oak (Quercus ilex L.). J. Hered. 101, 717–726 (2010).

Aparicio, A., Hampe, A., Fernandez-Carrillo, L. & Albaladejo, R. G. Fragmentation and comparative genetic structure of four Mediterranean woody species: Complex interactions between life history traits and the landscape context. Divers. Distrib. 18, 226–235 (2012).

Matesanz, S. & Valladares, F. Ecological and evolutionary responses of Mediterranean plants to global change. Environ. Exp. Bot. 103, 53–67 (2014).

Fahrig, L. Relative effects of habitat loss and fragmentation on population extinction. J. Wildl. Manag. 61, 603–610 (1997).

Botequilha Leitão, A. & Ahern, J. Applying landscape ecological concepts and metrics in sustainable landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 59, 65–93 (2002).

Olff, H. & Ritchie, M. E. Fragmented nature: Consequences for biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 58, 83–92 (2002).

Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 487–515 (2003).

Zheng, L., Wang, Y. & Li, J. Quantifying the spatial impact of landscape fragmentation on habitat quality: A multi-temporal dimensional comparison between the Yangtze River Economic Belt and Yellow River Basin of China. Land Use Policy 125, 106463 (2023).

Damschen, E. I. Landscape corridors. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 467–475 (Elsevier, 2013).

Modica, G. et al. Implementation of multispecies ecological networks at the regional scale: Analysis and multi-temporal assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 289, 112494 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, National Operation Program (Programma Operativo Nazionale – PON), Research and Innovation, Green Themes, Action IV. 6. Project Title “Conservation of species and habitats of community importance: seed biology, ex situ and in situ conservation” (D.M. 1062, 10/08/2021). The authors are thankful to all the people who gave assistance during field activities and laboratory experiments.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, National Operation Program (Programma Operativo Nazionale—PON), Research and Innovation, Green Themes, Action IV. 6. Project Title “Conservation of species and habitats of community importance: seed biology, ex situ and in situ conservation” (D.M. 1062, 10/08/2021). The authors are thankful to all the people who gave assistance during field activities and laboratory experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that they contributed equally to each part of the manuscript. G. B. and V.V.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing original draft, writing review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the collection of plants were followed. All authors have read, understood, and have complied as applicable with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of Authors”, as found in the Instructions for Authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonanno, G., Veneziano, V. Intrapopulation germinability may help the Mediterranean plant species Poterium spinosum L. to cope with climate changes and landscape fragmentation. Sci Rep 14, 22235 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73021-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73021-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mediterranean mountain germination syndrome: here the story of the endemic plant Anthemis aetnensis (Mt. Etna, Italy) facing climate and land-cover changes

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)