Abstract

Single-vehicle crashes, particularly those caused by speeding, result in a disproportionately high number of fatalities and serious injuries compared to other types of crashes involving passenger vehicles. This study aims to identify factors that contribute to driver injury severity in single-vehicle crashes using machine learning models and advanced econometric models, namely mixed logit with heterogeneity in means and variances. National Crash data from the Crash Report Sampling System (CRSS) managed by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) between 2016 and 2018 were utilized for this study. XGBoost and Random Forest models were employed to identify the most influential variables using SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), while a mixed logit model was utilized to model driver injury severity accounting for unobserved heterogeneity in the data collection process. The results revealed a complex interplay of various factors that contribute to driver injury severity in single-vehicle crashes. These factors included driver characteristics such as demographics (male and female drivers, age below 26 years and between 35 and 45 years), driver actions (reckless driving, driving under the influence), restraint usage (lap-shoulder belt usage and unbelted), roadway and traffic characteristics (non-interstate highways, undivided and divided roadways with positive barriers, curved roadways), environmental conditions (clear and daylight conditions), vehicle characteristics (motorcycles, displacement volumes up to 2500 cc and 5,000–10,000 cc, newer vehicles, Chevy and Ford vehicles), crash characteristics (rollover, run-off-road incidents, collisions with trees), temporal characteristics (midnight to 6 AM, 10 AM to 4 PM, 4th quarter of the analysis period: October to December, and the analysis year of 2017). The findings emphasize the significance of driving behavior and roadway design to speeding behavior. These aspects should be given high priority for driver training as well as the design and maintenance of roadways by relevant agencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Speeding is a highly dangerous driving behavior that poses a significant risk to traffic safety, leading to devastating consequences in terms of fatalities and serious injuries. In the United States, speeding-related fatalities account for a quarter of all traffic-related deaths. Furthermore, approximately 30% of these fatalities result from single-vehicle crashes caused by speeding1. This issue is not limited to the US alone; speeding has been a major contributing factor in traffic fatalities and injuries worldwide. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) defines a speeding-related crash as one in which the police officer determines that excessive speed, surpassing the posted speed limit, or engaging in a race played a role, or the driver was charged with a speeding-related offense1. Additionally, a speeding-related fatality is defined as any death resulting from a crash related to speeding1. Figure 1 illustrates the trends in fatalities and fatalities per 100 million vehicle miles traveled (VMT) caused by speeding. Notably, there was a 17% increase in speeding-related fatalities in 2020, with 11,258 lives lost, and a further 23% increase in 2021, with 11,780 lives lost, compared to 2019’s figures of 9,5921. These numbers equate to an alarming average of 30 to 32 lives lost every day on our roads in recent years (2020-21), lives that could have been saved through the implementation of practical measures to address the problem. As such, speeding behavior poses a serious safety challenge considering a few critical factors.

The Impact of speeding behavior has been a pervasive safety challenge universally, contributing to a considerable number of traffic fatalities and injuries each year, with societal losses in high-, medium-, and low-income countries. According to the NHTSA, speeding was a factor in 26% of all traffic fatalities in the United States in 2019. This alarming statistic underscores the need to address speeding as a major public safety concern.

Single-vehicle crash dynamics indicate drivers’ losing control due to excessive speed, particularly at risky combinations of factors, such as curves, wet or icy roads, and adverse weather conditions. High speeds influence the driver’s ability to react to unexpected obstacles, sharp turns, or sudden changes in road conditions. Additionally, the kinetic energy of impact in high-speed crashes is significantly greater (square of velocity), leading to more severe injuries or fatalities. Contributing Factors, that lead to the prevalence of speeding-related single-vehicle crashes, include the following:

-

Driver Behavior: Risk-taking behaviors, such as aggressive driving and overestimating driving skills, are common characteristics among those who speed on the road.

-

Road Conditions: Poor Road maintenance, lack of signage, and hazardous weather conditions can contribute to the risks associated with speeding.

-

Vehicle Factors: High-performance vehicles (modern technology of airbags, side curtain, with high horsepower) may encourage drivers to exceed speed limits, while older vehicles might lack modern safety features to mitigate the impact of high-speed crashes.

-

Environmental Factors: Rural roads, which are often less maintained and have higher speed limits, see a higher incidence of speeding-related single-vehicle accidents compared to urban areas.

The consequences and Economic Impact of speeding-related single-vehicle crashes extend beyond the immediate physical harm to the driver and passengers. These crashes impose significant economic costs on society, including medical expenses, lost productivity, property damage, and emergency response costs. According to a study by IIHS, speeding-related crashes cost an estimated $52 billion annually in the United States.

Given the heightened concern surrounding the risky behavior of speeding, it is crucial to investigate the factors that contribute to the injury severities in speeding-related crashes. Speeding, whether it involves exceeding the speed limit or variations in speed, is strongly associated with the risk of crashes and the resulting injury severities. This is primarily due to the excessive kinetic energy dissipated upon impact between vehicles or between a vehicle and a fixed object and rollover crashes. Various factors have been shown to influence the choice of excessive or inappropriate speed, including age, gender, attitudes, safety perception, alcohol consumption, number of occupants in the vehicle, roadway geometry, road-surface conditions, type of vehicle, vehicle power, and ambient weather conditions2,3,4,5.

In this study, unlike previous studies, we approached the analysis of speeding by considering it as an entire data sample, rather than solely as an indicator variable. We measured speeding as the difference between the estimated travel speed (provided by the police officer) and the posted speed limit for the corresponding road segment. Other studies typically utilized ‘speeding’ as an indicator variable obtained from police-reported crash databases. Furthermore, unlike most previous studies6,7,8,9, we established a baseline scenario where the difference between travel speed and the posted speed is zero. This allowed us to compare the effects of various factors on driver injury severities.

Our study focused on developing models for driver injury severity, considering unobserved factors related to independent variables from police-reported crash databases across all states in the country. These factors include roadway-related and crash-specific variables readily available in the database, such as weather conditions, lighting, surface type, roadway classes, roadway characteristics, speed limit, travel speed, roadside information, driver age and gender, physical condition, maneuvers, violation history, vehicle make, model, model year, displacement, and vehicle type. We utilized the Crash Report Sampling System (CRSS) database, which contains sampled crash data from across the entire country, to analyze the potential severity of injuries in single-vehicle crashes related to speeding within a multivariate severity modeling framework. Our analysis employed machine learning algorithms to identify contributing factors to driver injury severity levels, and subsequently utilized advanced econometric techniques that allowed the mean and variance of the random parameters to vary across observations in the dataset. This approach better accounted for unobserved heterogeneity in the dataset extracted from the CRSS database system. Temporal and spatial inability was not the focus of this study. A future study built on the understanding and knowledge from this study will be the motivation for further exploration.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) methods have been widely used for feature selection. While ML methods were once considered black-box approaches, recent advancements and research on interpreting ML models have made them more transparent and interpretable. Among the various ML methods, Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost) and Random Forest (RF) have emerged as the most employed algorithms in traffic crash studies10,11,12,13. To interpret the results of machine learning models, many studies have extensively used SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanation) in recent years14,15,16. SHAP is a visualization measure that provides insight into how different features influence the model.

The application of random parameter logit models, also known as mixed logit models, has garnered significant attention due to their ability to incorporate mixing distributions. These models are considered a promising alternative approach in injury severity analysis. One advantage of this approach is its consideration of unobserved heterogeneity by allowing certain variables to vary across the population. This makes the mixed logit model superior to fixed-parameter models17. Previous research studies have demonstrated the capability of mixed logit models in considering unobserved effects, such as driver behavior, roadway characteristics, and environmental factors18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

The paper is organized as follows: the next section provides a review of the existing literature on driver injury severity in speeding-related crashes, as well as methodological literature on injury severity modeling. It also describes machine learning algorithms and the approach for incorporating heterogeneity. This is followed by details of the CRSS data and the empirical setting. Finally, we explain the results of the machine learning algorithm and econometric modeling, including the marginal effects of the variables. The paper concludes with a summary of our findings.

Literature review

Several studies are identifying speeding as a key contributing factor to severe injuries using crash, naturalistic data, and driver surveys at state or country-level data. In 2022, Se et al.26 researched the causes of severe injuries in crashes in Thailand, revealing that factors such as vehicle type, road conditions, and regional location consistently influenced the likelihood of severe injuries in both speeding and non-speeding incidents. This study found that the use of restraints and certain vehicle types was key in reducing injury severity, while factors like alcohol influence significantly increased the risk. Das et al.9 analyzed Louisiana crash data from 2010 to 2016 to identify patterns leading to speeding-related motorcycle crashes, resulting in six distinct clusters associated with high crash likelihood. These clusters include single motorcycle crashes on low-volume two-lane roadways, older motorcyclists involved in undivided curve crashes, various intersection crashes, fatal left turn intersection incidents, lane splitting sideswipes on busy roads, and crashes on open country at-grade locations during wet pavement conditions. In 2021, Perez et al.8 analyzed naturalistic driving data and driver questionnaire responses to understand the factors affecting speeding likelihood, finding that both age and gender are significant influencers. Their results indicated that younger drivers (16–24 years old) are 1.5 times more likely to speed than those 80 or older, males are more likely to speed than females, and the likelihood of speeding is higher in lower speed limit zones, with odds 9.5 times greater in 10–20 mph zones compared to those over 60 mph. Islam and Mannering27 investigated the too-fast for rainy conditions between male and female drivers in Florida. Another study by Islam and Mannering21 found that drivers who exceeded the speed limit by more than 10 mi/hr were a consistent temporally stable predictor of driver injuries where aggressive driving was identified. Kong et al.28 extracted naturalistic driving data collected by the Safety Pilot Model Deployment (SPMD) program to evaluate the relationship between trip/driving/roadway features and speeding behavior. Hong et al.7 evaluated the effects of socio-demographic factors on motorcycle speeding behavior by developing linear network autocorrelation models. However, in another study by Fernandes et al.29, the researchers concluded that female drivers had more risky behavior in terms of speed violations. In 2019, Cheng et al.30 determined the factors that influence speeding violation behavior using electronic law enforcement data obtained from the public security administration of Wujiang.

Yadav and Velega31 explored the effect of different Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) levels on drivers’ speed and their ability to avoid crashes in case of sudden events by simulating driving experiments in rural and urban conditions. Chen et al.6 used principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering to determine the contributing factors to severe crash injuries in China. Ma et al.32 developed a partial proportional odds model to identify the contributing factors to crash injury severity using crash records collected on rural two-lane highways in China. Moreover, Abegaz et al.33 developed a generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds model to investigate the contributing factors to crash severities using crash data collected from June 2012 to July 2013 on one of Ethiopia’s main and busiest highways. In 2013, Hassan and Al-Falah34 developed a logistic regression model to categorize crashes into fatal and non-fatal crashes and identify the contributing factors to them. Council et al.35 developed a speeding-related crash typology to identify the crash, vehicle, and driver features that increase the probability of speeding-related crashes.

A summary of the key variables used by previous studies, as well as their increasing or decreasing effects on speeding crash severity and frequency, is provided in Table 1.

Data description

Single-vehicle crashes caused by driving above or within the speed limit were extracted from the Highway Safety Information System (CRSS) database between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2018. CRSS is a sample of police-reported crashes involving all types of motor vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists, ranging from property damage-only crashes to those that result in fatalities. CRSS obtains its data from a nationally representative probability sample selected from the estimated 6 to 7 million police-reported crashes that occur annually. This determination of driving within or exceeding was made based on the difference between travel speed and speed limit. The process of determining if a vehicle was speeding involved calculating the difference between its speed and the posted speed limit. A zero difference meant the vehicle was within the speed limit, while a positive difference indicated it was exceeding the speed limit. This method provided a clear and measurable way to categorize driving behavior about speed limits. Records from various datasets, including crash, person, vehicle, violation, distraction, vpicdecode, vpictrailerdecode, and pbtype (providing crash information for pedestrians, bicyclists, and individuals on personal conveyances), were aggregated and filtered. Data from multiple sources, such as crash, person, vehicle, violation, and distraction datasets, were compiled and processed. This included vpicdecode, a data file offering vehicle specifications derived from the Vehicle Identification Number (VIN), and vpictrailerdecode, providing similar information for trailers. Additionally, the pbtype dataset, which offers crash details involving pedestrians, bicyclists, and personal conveyance users, was also incorporated into the aggregated and filtered data set. The crash, vehicle, person, violation, and distraction files were linked based on case and vehicle numbers. The pbtype and person files were integrated, excluding information related to pedestrians, bicyclists, and individuals on personal conveyances. The vpicdecode and vpictrailerdecode files were combined to obtain detailed car information. Throughout the merging process, the unique crash case number and associated vehicle numbers were validated to ensure a high-quality merged dataset. Figure 2 illustrates the data processing and linkage process which resulted in the final data sample for modeling.

After merging, the data was filtered to include only single-vehicle crashes and driver information, considering the total number of vehicles involved in a crash and the seating position of the person. The filtering process for driving within the speed limit (where the difference between travel speed and speed limit was zero) resulted in a dataset of 3,450 crashes. For driving exceeding the speed limit (where the difference was positive), there were 2,299 crashes over the three-year analysis period (2016–2018).

Injury severity was defined as the level of injury sustained by the most severely injured driver in each crash. In the single-vehicle crashes, the five driver injury severity levels (fatal, suspected serious injury, suspected minor injury, possible injury, and no injury/property damage only) were aggregated into three levels: severe injury crashes (37% in exceeding the speed limit vs. 20% in within the speed limit of the respective crash data sample), minor injury crashes (33% in exceeding the speed limit vs. 32% in within the speed limit), and no injury crashes (30% in exceeding the speed limit vs. 48% in within the speed limit) – see Fig. 3. Figure 3 highlights the importance of estimating the effects of factors influencing the severity levels of such crashes, where injury severities are higher for those exceeding the speed limit compared to those within the speed limit.

When examining different types of road facilities, it was observed that on two-way undivided roadways, 47% of crashes involved single vehicles traveling, while 52% of them occurred beyond the speed limit. In comparison, on two-way undivided roadways with a positive median barrier, 25% of crashes were involved, while 18% occurred beyond the speed limit. Furthermore, on two-way roadways with an unprotected median, 11% of crashes involved vehicles at the speed limit, and 9% of them occurred beyond the speed limit.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables found statistically significant in the models. These variables are categorized into temporal, weather, crash, vehicle, roadway, crash, and driver characteristics.

SD = Standard Deviation.

Methodology

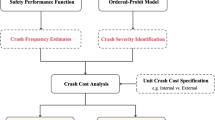

Previously, researchers have developed machine learning and econometric models to compare their performance in predicting crash severities36,37. They concluded each of these methods outweigh the other one in different scenarios. However, these studies are not comprehensive since they did not attempt to explore both severity prediction and driving behavior using machine learning and econometric models simultaneously. The extent of crash information collected and reported by the officers could lead to limited data compiled in the crash database compared to the wealth of information present at the crash scene that could have been extracted. Accounting for unobserved factors (not captured in the reported crash data in the database), injury severity modeling with mixed logit with heterogeneity in means and variances was found to be more promising to uncover contributing factors leading to crash and crash outcomes focusing on driving behaviors. In this study, machine learning and advanced econometric models were implemented to take advantage of the values of both approaches to capture variables in the model estimation. In the advanced machine learning process, XGBoost and Random Forest, with SHAP values, were applied first. A recent study by Hasan et al.38 emphasized the effectiveness of XGBoost and Random Forest algorithms in identifying the importance of variables. Secondly, econometric models were employed to quantify the effect of the variables (marginal effects) on the driver injury severity in single-vehicle crashes. Figure 4 below shows the steps covered with machine learning models and the rest of the process with the advanced econometric model. The link between machine learning and the econometric model is the top variables selection by SHAP values from two algorithms of machine learning (Random Forest and XGBoost) and qualification of some of the overlapping variables including others to estimate the random parameters multinomial logit with heterogeneity in means and variances. In general, a significant advantage of many machine learning algorithms is their ability to autonomously identify pertinent features from a broad array of variables. This capability is instrumental in pinpointing key predictors without the need for predefining a model grounded in theoretical assumptions. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that machine learning techniques serve as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, traditional econometric models. Basically, in this context, machine learning algorithm provides a list of important variables (say, top 10 or 15 variables) to consider in the econometric modeling framework where driver injury severity is modeled with three simultaneous equations. These algorithms would not guarantee that those variables will be statistically significant although checking their descriptive statistics, these variables would be considered as the top variables in the econometric modeling rather than just trying any variables in the model (some sort of context-driven variable). In many instances, simplified variables rather than more classified variables identified in the machine learning algorithm, would stand out as statistically significant in the econometric modeling. These techniques have the potential to reveal patterns and relationships that may not be immediately evident or are typically overlooked in conventional models.

Machine learning models

XGBoost, also known as an ensemble technique, is integrated based on gradient-boosted decision trees. This algorithm was initially proposed in 2002 by Friedman39. XGBoost algorithm has achieved promising results in many research fields40,41,42,43. This algorithm consists of a set of decision trees in which every tree learns from the prior tree and affects the following tree. XGBoost with k tree functions can be formulated as follows44:

where \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) is the estimated crash severity after tth iterations, k is the number of the additive trees, t is the number of iterations, \({f}_{k}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the kth tree function for variables \({x}_{i}\), \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{(t-1)}\) is the predicted response value for the final iteration, and \({f}_{t}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the tree function of ith iteration.

The objective function for minimizing the loss \(l\left({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i}\right)\) can be shown as follows:

where \({\Omega}\left({f}_{t}\right)\) is the regularization term for preventing overfitting and reducing the complexity, T is the number of leaves, \({\omega}_{j}^{2}\) is the L2 norm of jth leaf scores, and n is the total number of crashes in sample data.

Random Forest, also known as the decision forest technique, is an ensemble learning method that was initially created by T. Kam Ho45. This algorithm is comprised of a set of individual decision trees functioning as an ensemble. Each individual decision tree predicts a class, and eventually, the class having the highest vote is selected as the final model prediction. Due to its simplicity, Random Forest can be used for both classification and regression problems, making it one of the most used algorithms.

In this study, SHAP is used to interpret the machine learning output results indicating the importance of each feature on the model. Let us assume that \({x}_{i}\) is the ith sample, \({x}_{ij}\) is the jth feature of the ith sample, and \({y}_{i}\) is the predicted value for the ith sample in the model, and \(\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the baseline of the whole model. The SHAP value can be calculated using the following equation46:

where \(f({x}_{i},1)\) is the SHAP value for the first feature in the ith sample.

Finally, for evaluating the performance of the developed machine learning models, three commonly used evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, and F-1 score, were used. The considered evaluation metrics are defined as follows47:

where TP: Samples are positive and correctly assigned to the positive category. TN: Samples are negative and correctly assigned to the negative category. FP: Samples are negative, but wrongly assigned to the positive category. FN: Samples are positive but wrongly assigned to the negative category.

Econometric models

A random parameter logit model with heterogeneity in means and variances was estimated to account for any possible heterogeneity in the dataset focusing on single-vehicle crashes due to exceeding the speed limit and driving within the speed limit in the US. Restricting the variable effect to be the same across observations (i.e., the standard mixed logit formulation) may cause biased estimates and erroneous inferences. The conventional crash databases extracted from the police reports cover part of a wealth of information originating from the crash scene. Considering the given limitations in the police-reported crash database, the intent of these “heterogeneity” models provides accurate inferences by explicitly accounting for observation-specific variations in the effects of influential factors (as unobserved heterogeneity). The extensive discussions and justifications for accounting for unobserved heterogeneity in crash data modeling are highlighted in a study by Mannering et al.48. Considering the paradigm shift from the other traditional models, if unobserved heterogeneity is ignored, and the effects of observable variables are restricted to be the same across all observations, the model will be mis specified and the estimated parameters will, in general, be biased and inefficient, which could in turn lead to erroneous inferences and predictions.

In this study, a random parameter multinomial logit model that accounts for possible heterogeneity in the means and variances of the random parameters has been utilized to address the possible unobserved heterogeneity in the single-vehicle crash data due to exceeding the speed limit and driving within the speed limit in the analysis period of three years of 2016 to 2018 (inclusive). The injury severity of drivers in single-vehicle crashes is considered with possible injury outcomes of no injury, minor injury (possible injury and non-incapacitating injury), and severe injury (incapacitating injury and fatality). Following the recent work, the modeling approach starts by defining a function that determines injury severity,

where Sin is an injury-severity function determining the probability of injury-severity outcome i in single-vehicle crash n, Xin is a vector of explanatory variables that affect single-vehicle crash injury-severity level i, βi is a vector of estimable parameters, and εin is the error term. If this error term is assumed to be generalized extreme value distributed, a standard multinomial logit model results as McFadden49:

where Pn(i) is the probability that single-vehicle crash n that will result in driver-injury severity outcome i and I is the set of the three injury-severity outcomes. The following form of Eq. 2 allows for the possibility of one or more parameter estimates in the vector βi to vary across each crash (i.e., each observation)50:

where f(βi|φi) is the density function of βi and φi is a vector of parameters describing the density function (mean and variance), and all other terms are as previously defined.

To account for the possibility of unobserved heterogeneity in the means and variances of parameters, let βin be a vector of estimable parameters that varies across single-vehicle crashes defined as (a similar formulation used by20,21,22,23,24,25,51,52 in other injury severity contexts.

where βi is the mean parameter estimate across all single-vehicle crashes, Zin is a vector of crash-specific explanatory variables that captures heterogeneity in the mean that affects injury-severity level i, Θin is a corresponding vector of estimable parameters, Win is a vector of crash-specific explanatory variables that captures heterogeneity in the standard deviation σin with corresponding parameter vector Ψin, and vin is a disturbance term.

During model estimation, several density functions (for example, uniform, triangular, log normal, Weibull, etc.) were empirically evaluated for the term f(βi|φi). However, normal distribution was found to be statistically superior to all and was used in model estimation (this finding is consistent with past work including20,21,51,53. The model estimations used simulated maximum likelihood with 1,000 Halton draws54,55,56.

Results and discussions

This section is explained with the identification of risk factors with machine learning and ranked by SHAP values and likelihood ratio tests on injury severity and estimated model parameters for exceeding the speed limit and driving within the speed limit in the USA.

Identification of top risky factors in speeding with machine learning

Two classification models, including XGBoost and Random Forest, were used to model the injury severity of vehicles driving within the speed limit. Afterward, SHAP values were employed to identify the top risky variables associated with the developed models. In this study, 75% of the data were randomly selected as the training set. The remaining 25% were used to test the models. Moreover, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) algorithm was applied to deal with the imbalanced variables in the dataset. One way of addressing imbalanced variables is to oversample the minority class, which can be done by duplicating examples in the minority class, although these examples do not add any new information to the model. This is a type of data augmentation for the minority class and is referred to as the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique for Handling Edges (SMOTHE)57.

Machine learning estimation results

As mentioned earlier, three evaluation measures, including accuracy, precision, and F-1 score, were selected for evaluating the performance of machine learning models. Random forest models outperform the XGBoost models for both vehicles driving within and beyond the speed limit. Regarding vehicles driving beyond the speed limit, an accuracy of 60.3%, a precision of 60.0%, and an F-1 score of 60.0% were obtained for the Random Forest model. On the other hand, an accuracy of 59.5%, a precision of 59.3%, and an F-1 score of 59.3% were recorded for the XGBoost model. In terms of the vehicles driving within the speed limit, the best accuracy of 73.3%, the precision of 73.0%, and the F-1 score of 72.8% were achieved for the Random Forest model. Finally, for the XGBoost model, the accuracy, precision, and F-1 score were recorded as 71.7%, 71.5%, and 71.3%, respectively. Figures 5 and 6 present the confusion matrix for the developed XGBoost and Random Forest models, respectively.

Top variables

Figures 7 and 8 show the top ten variables and their SHAP values for XGBoost and Random Forest models. Based on the XGBoost model, variables including shoulder and lap belt used (REST), no rollover (ROLLRNA), tree (TRE), body type other (BDYTYPOTHER), drinking (DRK), right or left roadside departure (ROR), newer vehicles (VAGE5), dry surface (DRY), driver age below 26 (DAGE25), and male driver (ML) were found to be the top contributing factors related to the vehicles driving beyond the speed limit. It was also found that variables including shoulder and lap belt used (REST), no rollover (ROLLRNA), on the roadway (RLRDOR), body type other (BDYTYPOTHER such as buses, motor home, snowmobiles, farm vehicles, etc.), two-way, not divided roadway (W2UD), driver age below 26 (DAGE25), one occupant (OCCS1), the crash year 2018 (Y18), live animal (ANML), and male driver are the top factors associated with driving within the speed limit.

Regarding the Random Forest model results, the factors including shoulder and lap belt used (REST), no rollover (ROLLRNA), tree (TRE), rollover (RLLO), body type other (BDYTYPOTHER), motorcycle (MC), rollover, unknown type (ROLLUN), drinking (DRK), right or left roadside departure (ROR), south region of the country (REGION3) are the leading variables in driving beyond the speed limit. Moreover, shoulder and lap belt used (REST), no rollover (ROLLRNA), on the roadway (RLRDOR), live animal (ANML), rollover (RLLO), body type other (BDYTYPOTHER), newer vehicles (VAGE5), driver age below 26 (DAGE25), and motorcycle (MC) were the top variables affecting the vehicles driving within the speed limit. The south region includes Maryland, Delaware, Washington DC., West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas in the South (Region 3) per CRSS user manual.

It was notable that the top three variables were the same for both XGBoost and Random Forest models in driving beyond the speed limit. Similarly, the top three variables for both models were recorded the same in driving within the speed limit.

Test for differences in severity for beyond and within speed limit

After extensively testing for differences between injury severity on exceeding and speed limit and driving within the speed limit, it was determined that statistically significant differences existed in the injury severity data for exceeding and speed limit and driving within the speed limit. This was confirmed by a series of likelihood-ratio tests. To test for differences in injury severity for exceeding the speed limit and within the speed limit further, additional likelihood ratio tests were run as50,

where LL(βWithin Speed Limit, exceeding Speed Limit) is the log-likelihood at the convergence of a model containing converged parameters based on using beyond the speed limit data while using data from within speed limit data, and LL(βExceeding Speed Limit) is the log-likelihood at the convergence of the model using beyond speed limit-data, with parameters no longer restricted to using beyond speed limit converged parameters as is the case for LL(βWithin Speed Limit, Exceeding Speed Limit). Using the converged parameters of the beyond speed limit model as starting values and applying them to the within speed limit data gave X2 = 35.716 and, with 23 degrees of freedom, this also gave a χ2 confidence level of more than 95.9% that the null hypothesis that the injury severity on both segments is the same can be rejected. Similarly, using the converged parameters of the within-speed limit model as starting values and applying them to the beyond-speed limit data gave X2 = 69.028. With 23 degrees of freedom, this gave a χ2 confidence level of more than 99.9% that the null hypothesis that the injury severity in scenarios (within and beyond the speed limit) is the same can be rejected.

Econometric model estimation results

Mixed logit with heterogeneity in mean and variance for single-vehicle crashes for driving within the speed limit and exceeding the speed limit were presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The comparison of the marginal effects of these two models is presented in Table 5. The model has an overall statistical fit with a McFadden pseudo-R-squared value of 0.176 for driving within the speed limit and 0.129 for exceeding the speed limit. We note that the constant term specific to minor injury was found to be the only statistically significant random parameter that is normally distributed in both models. Considering the mean (-2.828) and standard deviation (5.082) of the random parameter (i.e., the constant specific to minor injury) in the model, it implies that the intercept for minor injury is more than zero for 28.89% of the target crashes (i.e., single-vehicle crashes for driving within the speed limit) and tend to increase the likelihood of minor injury. It was found that the mean of the random parameter varied by whether the crashes were on straight segments. In this model, the crashes on the straight segment decreased the mean of the random parameter making minor injury less likely. The variance of the constant for minor injury was a function of clear weather. Crashes in clear weather were less likely to be involved in minor injury making the variance of constant specific to minor injury smaller. Likewise, considering the mean (-4.684) and standard deviation (11.541) of the random parameter (i.e., the constant specific to minor injury) in the model, it implies that the intercept for minor injury is more than zero for 34.24% of the target crashes (i.e., single-vehicle crashes for exceeding the speed limit) and tend to increase the likelihood of minor injury. It was found that the mean of the random parameter varied by whether the drivers were restrained or not. In this model, when drivers were restrained, decreased the mean of the random parameter made minor injury less likely. The variance of the constant for minor injury was a function of clear weather. Crashes in clear weather were more likely to be involved in minor injury making the variance of constant specific to minor injury higher.

In addition to parameter estimates for the mixed logit with heterogeneity in means and variances, estimated marginal effects are also included in Table 3. Marginal effects indicate the effect a one-unit increase in an explanatory variable has on the injury-outcome probabilities.

Temporal characteristics

In comparison to other periods, single-vehicle crashes that exceeded the speed limit between midnight and 6 AM were more likely to result in severe injuries (with an average marginal effect of 0.0095) but less likely to result in minor injuries. On the other hand, single-vehicle crashes within the speed limit between 10 AM and 4 PM were more likely to result in minor injuries but less likely in severe injuries (with a marginal effect of 0.0138 for minor injuries vs. -0.0056 for severe injuries). Similarly, there was an opposite effect for minor injury crashes (with a marginal effect of -0.0016 on curved segments vs. 0.0224 on straight segments). Additionally, single-vehicle crashes in 2017 that occurred within the speed limit were more likely to result in severe injuries (with a marginal effect of 0.0090) but less likely to result in minor injuries.

Environmental characteristics

In comparison to other weather conditions, clear weather conditions were more likely to result in minor injury crashes (with an average marginal effect of 0.0749), but less likely to result in severe or no injury crashes for drivers within the speed limit. Conversely, single-vehicle crashes during daylight conditions, where drivers were within the speed limit, were likely to increase the occurrence of severe and minor injuries.

Crash characteristics

Compared to other crash types, single-vehicle rollover crashes involving drivers within the speed limit were likely to result in minor injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0464). A vehicle running off-road from the left side while driving within the speed limit would be more likely to result in severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0241). However, when drivers exceeded the speed limit, vehicles running off-road would be even more likely to result in severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0827). Notably, single-vehicle crashes involving collisions with trees would likely result in higher severe injuries when exceeding the speed limit compared to driving within the speed limit (average marginal effect of 0.0281 for exceeding the speed limit vs. 0.0244 for driving within the speed limit).

Vehicle characteristics

In comparison to other vehicle types, single-vehicle crashes involving motorcycles were twice as likely to result in higher severe injuries when exceeding the speed limit relative to driving within the speed limit (marginal effect of 0.0040 for exceeding the speed limit vs. 0.0020 for driving within the speed limit). Single-vehicle crashes with vehicle displacement volumes between 5,000 and 10,000 cc were more likely to result in severe injuries when exceeding the speed limit (average marginal effect of 0.0054). Moreover, newer vehicles manufactured within 5 years of the crash were 1.8 times more likely to result in higher minor injuries when exceeding the speed limit relative to driving within the speed limit (average marginal effect of 0.0243 for exceeding the speed limit vs. 0.0135 for driving within the speed limit).

Roadway characteristics

Compared to other types of roadways, single-vehicle crashes on non-interstate roadways involving drivers within the speed limit were more likely to result in minor injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0041). Single-vehicle crashes on two-way roadways with a positive median barrier involving drivers within the speed limit were more likely to increase the occurrence of severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0219). Conversely, single-vehicle crashes on two-way undivided roadways involving drivers exceeding the speed limit were more likely to increase the occurrence of severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0307). Regarding the roadway alignment, single-vehicle crashes on curved roadways involving drivers within the speed limit were more likely to result in severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0098). Conversely, single-vehicle crashes on straight roadways involving drivers exceeding the speed limit were more likely to result in severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0165). It is worth noting that single-vehicle crashes on dry surfaces involving drivers exceeding the speed limit were twice as likely to result in severe injuries compared to driving within the speed limit (average marginal effect of 0.0507 vs. 0.0258), whereas the difference in minor injuries was smaller (average marginal effect of 0.0093).

Driver characteristics

Male drivers involved in single-vehicle crashes were found to be more likely to experience severe injuries than female drivers (with an average marginal effect of 0.2591 vs. 0.0945) when exceeding the speed limit. Among different age groups, drivers between 35 and 45 years old involved in single-vehicle crashes were more likely to experience severe injuries when exceeding the speed limit. In comparison to other risky behaviors, reckless drivers involved in single-vehicle crashes were more likely to experience severe injuries when driving within the speed limit. Drivers who were not intoxicated and exceeded the speed limit in single-vehicle crashes were less likely to experience severe injuries (average marginal effect of -0.0560). Unrestrained drivers who exceeded the speed limit in single-vehicle crashes were more likely to experience severe injuries (average marginal effect of 0.0051). Importantly, restrained drivers in single-vehicle crashes were less likely to experience severe injuries when exceeding the speed limit relative to driving within the speed limit (average marginal effect of -0.1576 for exceeding the speed limit vs. -0.1405 for driving within the speed limit).

Out-of-sample simulation

In the context of this study, from a pragmatic point of view, the aggregate effect of change shifts between two driving behaviors considering the speed limit is of particular interest. Looking at the overall injury severity percentages, driving within the speed limit, the distribution of crashes among severity levels was 47.8% no injury, 32.3% minor injury, and 20.0% severe injury. For crashes involving driving exceeding the speed limit, this distribution among severity levels shifted to 30.2% no injury, 32.6% minor injury, and 37.2% severe injury. Thus, while the percentage of crashes resulting in severe and minor driver injuries declined over this period, there was a shift from severe and no injuries to no injuries (this is also reflected in Fig. 3). To explore this issue further with the estimated models, the parameters from the driving exceeding the speed limit model were used to forecast exceeding the speed limit (using actual crash characteristics from the crashes involving exceeding the speed limit crashes) and these predictions were compared with predictions based on the estimated driving within the speed limit parameters using exceeding the speed limit data. Please note that using driving within the speed limit estimated parameters with exceeding the speed limit data constitutes an out-of-sample prediction. While such prediction is trivial for fixed parameters models, it is much more complex for random parameters models since the full distribution of the random parameters must be considered when predicting. As discussed extensively by24, the prediction undertaken here is done by simulation, in this case using the same procedure as was used with the simulated maximum likelihood estimation. This predictive comparison provides an aggregate assessment of how overall injury severity probabilities have changed between two different driving behaviors while controlling for actual crash characteristics. In this case, driving within the speed limit parameters predicts 34.0% of crashes resulting in no injury in exceeding the speed limit instead of the estimated 29.4% (observed 30.2%), 23.7% of crashes resulting in minor injury instead of the estimated 32.5% (observed 32.6%) and 42.4% of crashes resulting in severe injury as opposed to the estimated 38.0% (observed 37.2%). As mentioned above, in looking at Fig. 2 and comparing driving within the speed limit and exceeding the speed limit, the observed crashes exceeding the speed limit have lower percentages of no injuries a higher percentage of severe injuries, and slightly higher minor injury crashes. The predictive comparison also shows that driving within the speed limit parameters predicts the same trend and is very close to the magnitude that was observed. This suggests that some of the observed injury-proportion trends shown in Fig. 2 are due to the specific characteristics of the observed crashes, but that fundamental differences in driving behavior in the influence that crash characteristics are having on injury probabilities are also playing a role. Some of these changes may be the result of improvements in vehicle safety features over time (lane-departure warning systems), roadway improvements (centerline and edge-line rumble stripes, cable median barriers, guard rails, etc.) or temporal changes in the risk profiles of individuals observed to be involved in crashes as discussed in21,24,27.

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed factors contributing to single-vehicle crashes in the US, considering both driving within the speed limit and exceeding the speed limit. We utilized a machine learning algorithm and a random parameters logit model with heterogeneity in mean and variance. The crash data was extracted from the national CRSS crash database system, covering the period from 2016 to 2018. We focused on three levels of crash injury severity: no injury, minor injury (combining possible and non-incapacitating injury), and severe injury (combining incapacitating and fatal injury). The estimated models incorporated a wide range of factors, including temporal, environmental, vehicular, crash, roadway, and driver characteristics.

In terms of the machine learning models, we identified several common variables that were relevant to both driving within and exceeding the speed limits. These variables included restraint system usage by the drivers, no rollover, vehicle body type as “other,” drivers in the age group younger than 25, and male drivers for the XGBoost models. For the Random Forest models, the common variables included restraint system usage by the drivers, no rollover, right and left road departure, rollover, and vehicle body type as “other.”

On the other hand, the estimated econometric models captured a total of 31 variables that significantly influenced driver injury severity in single-vehicle crashes for both scenarios. Out of these variables, five showed shared effects on both driving within and exceeding the speed limits. Some variables that were significant in driving within the speed limit model did not hold statistical significance in exceeding the speed limit model. The common variables included collisions with trees, motorcycle involvement, newer vehicles (manufactured within five years of the crash), dry road surface conditions, and restraint system usage by the drivers. The effect of these statistically significant variables indicated that the severity of driver injuries was higher when exceeding the speed limit compared to driving within the speed limit. Furthermore, certain driver characteristics, such as being male or female, belonging to the age group of 35 to 45 years, and driving without restraint usage, increased the likelihood of severe injury in single-vehicle crashes when exceeding the speed limit. Potential effective countermeasures include roadway design improvements, such as warning signs on risky road sections with higher speed limits, reassessment of advisory speed limits, and the implementation of appropriate crash cushions around trees. Additionally, drivers with a history of repeated speeding offenses should receive professional training to mitigate the risk of crashes. The findings of this research, based on a data-driven approach, contribute to the expanding body of knowledge in speed safety research.

In future analyses, it will be interesting to explore the speeding behavior by vehicle types which was investigated with distracted driving58. Moreover, we plan to explore the psychological, location-related factors and motivating risk factors utilizing the theory of planned behavior and apply machine learning and econometric models within a similar framework to explore speeding behavior quantitatively59,60,61. This effort aims to capture an important aspect of safety research and enhance our understanding of integrating these two methodologies for more effective future research and the development of new insights to support better countermeasures.

Data availability

This data source, managed by NHTSA, is available here: https://www.nhtsa.gov/file-downloads? p=nhtsa/downloads/CRSS/.

References

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), Traffic Safety Facts 2020: Speeding (DOT HS 813 320). (2022).

Finch, D., Kompfner, P., Lockwood, C. & Maycock, G. Speed, speed limits and accidents (1994).

Neuman, T., Slack, K., Hardy, K., Bond, V. & Potss, I. & Lerner, N. A Guide for Reducing speeding-related Crashes (Guidance for Implementation of the AASHTO Strategic Highway Safety Plan, 2009).

Anastasopoulos, P. C. & Mannering, F. L. The effect of speed limits on drivers’ choice of speed: a random parameters seemingly unrelated equations approach. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2016.03.001 (2016).

World Health Organization (WHO), Road Safety – Speed. (2020). https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/world_report/speed_en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed June 7, 2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Identification methods of key contributing factors in crashes with high numbers of fatalities and injuries in China. Traffic Inj. Prev.17, 878–883. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2016.1174774 (2016).

Hong, V. et al. Socio-demographic determinants of motorcycle speeding in Maha Sarakham, Thailand, PLoS ONE (2020). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243930

Perez, M. A., Sears, E., Valente, J. T., Huang, W. & Sudweeks, J. Factors modifying the likelihood of speeding behaviors based on naturalistic driving data. Accid. Anal. Prev.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106267 (2021).

Das, S., Mousavi, S. M. & Shirinzad, M. Pattern recognition in speeding-related motorcycle crashes. J. Transp. Saf. Secur.14, 1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2021.1877228 (2022).

Gu, T. & Yang, S. Duration Prediction for Truck Crashes Based on the XGBoost Algorithm (in: CICTP, Nanjing, 2019).

Li, F., Chen, C. H. & Khoo, L. P. Information requirements for vessel traffic service options. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng.10 (2016).

Ma, J. et al. Analyzing the leading causes of traffic fatalities using XGBoost and grid-based analysis: a city management perspective. IEEE Access.7, 148059–148072. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2946401 (2019).

Zhao, H., Yu, H., Li, D., Mao, T. & Zhu, H. Vehicle accident risk prediction based on AdaBoost-SO in VANETs. IEEE Access.7, 14549–14557. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2894176 (2019).

Parsa, A. B., Movahedi, A., Taghipour, H., Derrible, S. & Mohammadian, A. Toward safer highways, application of XGBoost and SHAP for real-time accident detection and feature analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2019.105405 (2020).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S. & Guestrin, C. Why should i trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier, in: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1135–1144 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939778

Štrumbelj, E. & Kononenko, I. Explaining prediction models and individual predictions with feature contributions. Knowl. Inf. Syst.41, 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10115-013-0679-x (2014).

Hensher, D. A. & Greene, W. H. The Mixed Logit Model: The State of Practice TITLE: The Mixed Logit Model: The State of Practice (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022558715350

Milton, J. C., Shankar, V. N. & Mannering, F. L. Highway accident severities and the mixed logit model: an exploratory empirical analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev.40, 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2007.06.006 (2008).

Islam, M. & Hernandez, S. Modeling injury outcomes of crashes involving heavy vehicles on Texas highways. Transp. Res. Rec. https://doi.org/10.3141/2388-05 (2013).

Islam, M., Alnawmasi, N. & Mannering, F. Unobserved heterogeneity and temporal instability in the analysis of work-zone crash-injury severities. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2020.100130 (2020).

Islam, M. & Mannering, F. A temporal analysis of driver-injury severities in crashes involving aggressive and non-aggressive driving. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2020.100128 (2020).

Islam, M. An analysis of motorcyclists’ injury severities in work-zone crashes with unobserved heterogeneity. IATSS Res.46, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2022.01.003 (2022).

Islam, M. The effect of motorcyclists’ age on injury severities in single-motorcycle crashes with unobserved heterogeneity. J. Saf. Res.77, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2021.02.010 (2021).

Islam, M. & Mannering, F. An empirical analysis of how asleep/fatigued driving-injury severities have changed over time. J. Transp. Saf. Secur.15, 397–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2022.2070812 (2023).

Islam, M. An empirical analysis of driver injury severities in work-zone and non-work-zone crashes involving single-vehicle large trucks. Traffic Inj. Prev.23, 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2022.2101643 (2022).

Se, C., Champahom, T., Jomnonkwao, S., Karoonsoontawon, A. & Ratanavaraha, V. Analysis of driver-injury severity: a comparison between speeding and non-speeding driving crash accounting for temporal and unobserved effects. Int. J. Inj Control Saf. Promot. 29, 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2022.2081983 (2022).

Islam, M. & Mannering, F. The role of gender and temporal instability in driver-injury severities in crashes caused by speeds too fast for conditions. Accid. Anal. Prev.153, 106039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106039 (2021).

Kong, X., Das, S., Jha, K. & Zhang, Y. Understanding speeding behavior from naturalistic driving data: applying classification based association rule mining. Accid. Anal. Prev.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105620 (2020).

Fernandes, R., Hatfield, J. & SoamesJob, R. F. A systematic investigation of the differential predictors for speeding, drink-driving, driving while fatigued, and not wearing a seat belt, among young drivers. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav.13, 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2010.04.007 (2010).

Cheng, Z., Lu, J., Zu, Z. & Li, Y. Speeding violation type prediction based on decision tree method: a case study in Wujiang, China. J. Adv. Transp.https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8650845 (2019).

Yadav, A. K. & Velaga, N. R. Alcohol-impaired driving in rural and urban road environments: Effect on speeding behaviour and crash probabilities. Accid. Anal. Prev.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105512 (2020).

Ma, Z., Zhao, W., Chien, S. I. J. & Dong, C. Exploring factors contributing to crash injury severity on rural two-lane highways. J. Saf. Res.55, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2015.09.003 (2015).

Abegaz, T., Berhane, Y., Worku, A., Assrat, A. & Assefa, A. Effects of excessive speeding and falling asleep while driving on crash injury severity in Ethiopia: a generalized ordered logit model analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev.71, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.05.003 (2014).

Hassan, H. M. & Al-Faleh, H. Exploring the risk factors associated with the size and severity of roadway crashes in Riyadh. J. Saf. Res.47, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2013.09.002 (2013).

Forrest, M., Council, M., Reurings, R., Srinivasan, S. & Masten Daniel Carter, Development of a Speeding-Related Crash Typology (2010).

Behnood, A. & Mannering, F. L. An empirical assessment of the effects of economic recessions on pedestrian-injury crashes using mixed and latent-class models. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.12, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2016.07.002 (2016).

Wu, Y. W. & Hsu, T. P. Mid-term prediction of at-fault crash driver frequency using fusion deep learning with city-level traffic violation data. Accid. Anal. Prev.150, 105910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105910 (2021).

Hasan, A. S., Jalayer, M., Das, S. & Kabir, M. A. B. Application of machine learning models and SHAP to examine crashes involving young drivers in New Jersey. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtst.2023.04.005 (2023).

Friedman, J. H. Stochastic gradient boosting. Comput. Stat. Data Anal.38, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9473(01)00065-2 (2002).

Ma, J. & Cheng, J. C. P. Identification of the numerical patterns behind the leading counties in the U.S. local green building markets using data mining. J. Clean. Prod.151, 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.083 (2017).

Torlay, L., Perrone-Bertolotti, M., Thomas, E. & Baciu, M. Machine learning–XGBoost analysis of language networks to classify patients with epilepsy. Brain Inf.4, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40708-017-0065-7 (2017).

Zheng, H., Yuan, J. & Chen, L. Short-term load forecasting using EMD-LSTM neural networks with a Xgboost algorithm for feature importance evaluation. Energies (Basel). 10, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10081168 (2017).

Zhang, L. & Zhan, C. Machine learning in rock facies classification: An application of XGBoost, in: International Geophysical Conference, Qingdao, China, 17–20 April 2017, Society of Exploration Geophysicists and Chinese Petroleum Society, pp. 1371–1374 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1190/IGC2017-351

Guo, M. et al. Older pedestrian traffic crashes severity analysis based on an emerging machine learning XGBoost. Sustainability. 13, 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020926 (2021).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests, in: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, IEEE Comput. Soc. Press, pp. 278–282 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.1995.598994

Yang, Y., Wang, K., Yuan, Z. & Liu, D. Predicting freeway traffic crash severity using XGBoost-Bayesian network model with consideration of features interaction. J. Adv. Transp.2022, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4257865 (2022).

Christiana Abikoye, O. et al. Text classification using data mining techniques: a review. Comput. Inf. Syst. J.22, 1–9 (2018).

Mannering, F. L., Shankar, V. & Bhat, C. R. Unobserved heterogeneity and the statistical analysis of highway accident data. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.11, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2016.04.001 (2016).

McFadden, D. Econometric models for probabilistic choice among products. J. Bus. (1981).

Washington, S., Karlaftis, M. G. & Mannering, F. L. Statistical and Econometric Methods for Transportation data Analysis (CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2020).

Alnawmasi, N. & Mannering, F. A statistical assessment of temporal instability in the factors determining motorcyclist injury severities. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2019.100090 (2019).

Waseem, M., Ahmed, A. & Saeed, T. U. Factors affecting motorcyclists’ injury severities: an empirical assessment using random parameters logit model with heterogeneity in means and variances. Accid. Anal. Prev.123, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.10.022 (2019).

Behnood, A. & Mannering, F. Determinants of bicyclist injury severities in bicycle-vehicle crashes: a random parameters approach with heterogeneity in means and variances. Anal. Methods Accid. Res.16, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amar.2017.08.001 (2017).

McFadden, D. & Train, K. Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J. Appl. Econom. 15, 447–470 (2000).

Train, K. E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation (Cambridge University Press, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511753930

Bhat, C. R. Quasi-random maximum simulated likelihood estimation of the mixed multinomial logit model. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol.35, 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-2615(00)00014-X (2001).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res.16, 321–357. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.953 (2002).

Islam, M. Unraveling the differences in distracted driving injury severities in passenger car, sport utility vehicle, pickup truck, and minivan crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev.196, 107444 (2024).

Kim, W., But, J., Anorve, V. & Kelley-Baker, T. Examining U.S. drivers’ characteristics in relation to how frequently they engage in speeding on freeways. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav.85, 195–208 (2022).

Ghasemzadeh, A. & Ahmed, M. Quantifying regional heterogeneity effect on drivers’ speeding behavior using SHRP2 naturalistic driving data: a multilevel modeling approach. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol.106, 29–40 (2019).

Cristea, M., Paran, F. & Delhomme, P. Extending the theory of planned behavior: the role of behavioral options and additional factors in predicting speed behavior. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav.21, 122–132 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was not funded by any funding agency and it is completely conducted based on academic research interest and efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Islam conceptualized and analyzed the data and developed the models, supervised and wrote the manuscript. Dr. Parisa, Anahita, and Deep conducted formal data analysis, wrote part of the manuscript. Dr. Jalayer conceptualized, supervised, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the mansucript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, M., Hosseini, P., Kakhani, A. et al. Unveiling the risks of speeding behavior by investigating the dynamics of driver injury severity through advanced analytics. Sci Rep 14, 22431 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73134-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73134-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Novel Typology of Fatal Crash Behaviors via Natural Language Processing

Data Science for Transportation (2025)