Abstract

While ventricular shunts are the main treatment for adult hydrocephalus, shunt malfunction remains a common problem that can be challenging to diagnose. Computer vision-derived algorithms present a potential solution. We designed a feasibility study to see if such an algorithm could automatically predict ventriculomegaly indicative of shunt failure in a real-life adult hydrocephalus population. We retrospectively identified a consecutive series of adult shunted hydrocephalus patients over an eight-year period. Associated computed tomography scans were extracted and each scan was reviewed by two investigators. A machine learning algorithm was trained to identify the lateral and third ventricles, and then applied to test scans. Results were compared to human performance using Sørensen–Dice coefficients, calculated total ventricular volumes, and ventriculomegaly as documented in the electronic medical record. 5610 axial images from 191 patients were included for final analysis, with 52 segments (13.6% of total data) reserved for testing. Algorithmic performance on the test group averaged a Dice score of 0.809 ± 0.094. Calculated total ventricular volumes did not differ significantly between computer-derived volumes and volumes marked by either the first reviewer or second reviewer (p > 0.05). Algorithm detection of ventriculomegaly was correct in all test cases and this correlated with correct prediction of need for shunt revision in 92.3% of test cases. Though development challenges remain, it is feasible to create automated algorithms that detect ventriculomegaly in adult hydrocephalus shunt malfunction with high reliability and accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ventricular shunts remain a common fixture in modern neurosurgical practice. Despite continued attempts at innovation and improvement, shunt failure rates remain high. Some series have estimated lifetime failure rates in excess of 40%1,2 with first year failure rates in adults exceeding 15% and annual failure rates of 5% per year thereafter3 In addition to patient morbidity, ventricular shunts also present a large economic cost to society. The total cost of implanted ventricular shunts in the United States has been estimated to exceed one billion dollars per year as far back as the year 2000, with shunt failure accounting for over 40% of inpatient admissions for shunts2.

Though most cases of shunt failure can be readily recognized, a small subset can be challenging to diagnose. Cases with reduced ventricular compliance, non-classic shunt failure symptoms, a slow onset of failure, or unusual shunt morphology all can increase the difficulty of making a good diagnosis. Moreover, though an armamentarium of methods, such as radionucleotide studies, direct shunt taps, and thermal flow studies, have been developed over the years to help sort through these difficult cases, all have their limitations.

We put forward that machine learning, and specifically computer vision, could potentially help in these scenarios. Computer algorithms can easily assess three-dimensional metrics, such as volume and morphology, whereas traditional manual methods, such as Evan’s ratio and third ventricular width, only capture a single dimension of the ventricular system4. Previous work has shown that three-dimensional analysis improves the sensitivity, inter-rater reliability, and practitioner confidence in detecting changes in ventricular volume5. Moreover, computer algorithms, once trained, have the potential to be fast and consistent, enabling functions that are impractical for a human evaluator. For example, the marginal time to calculate ventricular volume for every scan in a patient’s lifetime is negligible for computerized methods and could allow for a form of longitudinal tracking that would not otherwise be available.

In recent years, a number of studies have looked at using computer vision and machine learning techniques to assess the ventricles in hydrocephalus. Multani et al. have used computer vision techniques to perform “quantitative computed tomography (CT) ventriculography”, demonstrating high sensitivity in predicting eventual need for ventricular shunting in patients undergoing external ventricular drain clamp trials in the intensive care unit6. Quon et al.7 has also examined this in pediatric hydrocephalus patients, using a computer vision model to automatically segment the ventricles of magnetic resonance images (MRI) in pediatric hydrocephalus patients. Moreover, Hale et al.8 has examined using neural networks to look at integrating clinical, surgical, and radiologic variables at the time of initial placement to predict long-term shunt failure within 5 years of placing a shunt, demonstrating high sensitivity for machine learning predictive algorithms.

A number of challenges still remain, however, in translating these techniques to detecting shunt failure in adult hydrocephalus patients. First, much previous work has been done in pediatric hydrocephalus patients, but it remains unclear if similar approaches are applicable to the shunted hydrocephalus adult population as they generally have a different pathology underlying hydrocephalus (e.g., subarachnoid hemorrhage)7,8. In addition, much work has mostly focused on predicting eventual shunt failure6,8 and has not investigated the detection of shunt failure at the point of care, which focuses on a specific use case for the technology. Moreover, most previous work has utilized MRI data as opposed to CT scans, which are more commonly used in adult patients and present their own set of unique challenges in processing including a smaller set of images to make predictions, as well as a unique set of distortion artifacts (e.g., hemorrhage, streak artifact from implanted devices) that algorithms must know how to handle7. Finally, many previous attempts are reliant on inputs that require a human to manually extraction specific parameters from either the clinical chart or imaging data8. This effort is time-intensive and limits the clinical applicability of such algorithms when deployed at scale.

Here, we propose a method for fully automated shunt failure detection that derives directly from the imaging data. This is implemented through training a convolutional neural network for automated segmentation of the lateral and third ventricles, which in turn is used to calculate ventricular volumes for comparison. Our goal was to investigate and highlight how such a method could be applied to an adult hydrocephalus population and serve as a basis for future development and implementation at scale.

Methods

Patient selection

We retrospectively identified a consecutive series of adult hydrocephalus patients (ages 18 and older) who had a history of ventricular shunt implantation at our institution. All serial non-contrasted head CT scans were obtained from these patients that occurred between January 2010 and December 2020. As the nature of our method involved comparison of serial scans, we excluded patients with only one CT scan, as two or more CT scans were needed for comparison in our study. We did not include MRI scans or CT angiography scans. No exclusion was based on gender, underlying etiology of hydrocephalus, length of shunt implantation, or ventricular configuration/morphology.

Scan screening and data partitioning

These scans were then manually segmented by two human reviewers each. Segmentations were performed by either a senior medical student or neurosurgical resident and verified by an attending neurosurgeon. For each scan, the reviewer first confirmed the presence of a ventricular shunt and ensured the study quality allowed for visualization of the third and bilateral lateral ventricles. Thereafter, each human reviewer labeled the ventricular system (i.e., manual segmentation) consisting of the third ventricle and the bilateral lateral ventricles. Reviewers were given a standardized, written set of instructions on how to perform the segmentation to produce as much consistency as possible.

Sørenson–Dice coefficients (i.e., Dice scores) were calculated between the two reviewers’ segmentations. Sørensen–Dice coefficients (i.e., Dice scores) are a commonly used metric for the quality of segmentation that accounts for baseline differences in the class frequency. Scores range from 0.0 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating better performance. For any scan where there was significant disagreement, defined as either disagreement on if the scan was of sufficient quality or if Dice scores between the two humans was less than 0.7, a third human reviewer segmented the scan. Only if two human reviewers could segment the ventricles of a scan with Dice score agreement between themselves greater than 0.7 was the scan included for final analysis. Scans not meeting this threshold were analyzed and possible contributing reasons (e.g., gross ventricular dysmorphia, acute hemorrhage, slit ventricle syndrome, etc.) were recorded.

Once a set of acceptable quality scans was thus identified, 10% of the scans were pseudorandomly selected via a computerized random number generator and reserved for final testing. The remaining 90% were used to train a convolutional neural network, a form of artificial neural network designed for computer vision tasks, for automated ventricular segmentation as specified below.

Patients included in the test set were characterized by demographics and clinical variables. These included baseline age, sex, reasons for original shunting, catheter position, type of valve (programmable vs. fixed pressure), presenting symptoms, whether there was ventriculomegaly documented by the treating clinical team in the electronic medical record, whether the patient went on to have a shunt exploration/revision within 7 days of the scan in question, and whether original symptoms resolved after shunt revision if it was performed.

Deep learning specifications and image pre- and post-processing specifications

Our image processing pipeline is demonstrated in Fig. 1. Our overall approach was to separate each CT scan into axial components for training and classification, and then re-combining them to yield a final volume. For each CT scan, we first separated it out into its individual two-dimensional axial slices. We then trained a convolutional neural network based on the total population of axial slices. During testing, each axial slice was segmented separately, and then the axial images were reassembled to yield a ventricular volume. This is similar to prior two-dimensional convolutional neural network models for ventricular deep learning segmentation7,9.

To standardize images for training of our model, raw three-dimensional head CT images were imported and then windowed to maximize contrast between brain parenchyma and ventricular spaces. Scans were cropped to a central region consisting of 320 × 320 × 17 voxels based on empiric testing, and then the scans were disaggregated in the axial plane and each axial image was in turn down-sized to a 256 × 256-pixel region for training and eventual segmentation. During segmentation a three-dimensional scan, these axial images were then re-expanded back to original size, re-aggregated, and then re-padded to return them the original scan dimensions.

Our specific convolutional neural network was structured as a two-dimensional U-net, which is currently one of the state-of-the-art models for image classification 10. Input images were obtained via random patch extraction (188 × 188 size patches, 8 patches per image), where specific random subsets of images are used to train the model to reduce memory limitations and avoid overfitting. Each training patch was further augmented with one of the following transformations: 90-degree rotation clockwise, 90-degree rotation counterclockwise, vertical reflection, and horizontal reflection. This was done to prevent overfitting of the model to any particular orientation or configuration of the nearby brain parenchyma and increase its robustness to translation and rotations during the testing phase.

The specific optimization function for training the network was cross-entropy loss weighted by median class label frequencies, which was empirically found to achieve the best results. The network was trained over 50 epochs, with an adaptive moment estimation (adam) optimizer, a form of stochastic gradient descent used to find optimal values in a high dimensional space (learning rate 0.001, piecewise learning rate, with a drop learning drop factor of 0.95 every epoch, size 50 mini-batches). Segments were put through post-processing after re-aggregation, including morphologic smoothing and removal of small islands. Skull stripping, where the skull is automatically removed from images to help with certain computer vision tasks for CT scans of the head, was not performed.

Model performance and shunt failure evaluation

We targeted 10% of our data to set aside for final testing. Notably, these scans all consisted of consecutive pairs of scans for a given patient to allow detection of interval change in evaluating for shunt failure. The segmentations from both human reviewers were also excluded from training to minimize over-fitting of the convolutional neural network.

To evaluate the performance of our model, we performed ventricular segmentation on each scan in our testing set. Scans were then compared to each human reviewer’s segmentation using Dice scores and calculated total ventricular volume.

For the purposes of shunt failure detection, we examined the most recent of each pair of scans. We then looked in the medical record to see if the patient required an operative shunt revision within 7 days of that scan, which we considered a shunt failure for the purposes of this study. We then compared the computer-calculated total ventricular volume from the most recent scan to its antecedent scan. Changes in volume (as a percent of total volume) were identified and used to set a threshold for declaring a shunt failure.

Analysis methods and materials

Dice scores and ventricular volumes were summarized with means and standard deviations. Dice scores were analyzed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and when found to significantly departure from normality, compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Ventricular volumes were compared between each of the human-derived and the computer-derived values using the paired t-test after all groups met threshold for normality by the Shapiro-Wilk test. A threshold of p < 0.05 was used for statistical significance.

Manual segmentation was performed with the help of 3D Slicer (3D Slicer, https://www.slicer.org)11. Deep learning software was developed using Matlab version 2021a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Training was conducted on an NVIDIA Geforce GTX 1060 graphics processing unit.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by our local Institutional Review Board (protocol number: 2015P002352). This study follows the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) Reporting Guidelines for diagnostic studies12.

Results

A total of 283 scans were initially screened for study suitability, with inter-reviewer Dice scores averaging 0.702 ± 27.3. Of these scans, 92 (32.7%) could not be included due to poor scan quality and low agreement between human reviewers (max Dice score < 0.7), leaving 191 scans for final analysis. Contributing factors for poor agreement between human reviewers included slit/low volume ventricles (52.1%), ventricular dysmorphia (38.0%), streak artifact (32.6%), acute hemorrhage (23.9%), rotated gantry or motion artifact (6.5%), and intraventricular air (5.4%).

The remaining 191 scans represented 50 unique patients, with 382 unique segmentations. 26 of these scans (13 pairs of scans from 13 patients, representing 13.6% of our dataset) were reserved for final testing, with the rest, consisting of 5610 axial slices once disaggregated, left for model training.

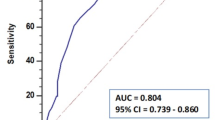

When compared to human reviewers, computer-derived ventricular segmentation had an average Dice score of 0.809 ± 0.094 (Fig. 2). Notably, this was less accurate than human reviewers when compared to each other as measured by Dice coefficients (mean inter-reviewer Dice score on any given scan: 0.902 ± 0.065, p < 0.0001).

However, when we compared computer-derived ventricular volumes to human-derived ventricular volumes, there were no statistically significant differences. Computer-derived ventricular volumes averaged 130.9 ± 67.2 milliliters (mL), which did not differ significantly from those of either the first human reviewer (127.2 ± 64.6 mL, p = 0.4343) or the second human reviewer (128.4 ± 65.0 mL, p = 0.6107).

In our test set of 13 patients, the mean age was 65.8 years (standard deviation: 12.4 years), and 6 of 13 (46.2%) were female (Table 1). The most common indications for shunting were normal pressure hydrocephalus (61.5%) and intracranial hemorrhage (15.4%). The vast majority (92.3%) had programmable valves, and the most common presentations were either asymptomatic (46.2%) or altered mental status (30.8%).

A total of 3 of our 13 patients had a shunt failure within 7 days after their scan (range: 1–3 days after scan). Changes in ventricular volume on computer-derived segmentations ranged from − 28.3 mL to + 51.1 mL, which was equivalent to percentage changes in ventricular volume ranging from − 19 to + 447% (Table 2). Setting thresholds for declaring shunt failure at increases of ventricular volume of + 10%, + 20%, and + 30% resulted in correct classification of ventriculomegaly when compared to electronic medical record documentation in 69.2% (9 of 13), 84.6% (11 of 13), and 100% (13 of 13) and correct prediction of shunt reoperation within 7 days of 69.2% (9 of 13), 76.9%, (10 of 13) and 92.3% (12 of 13) cases respectively.

Discussion

As artificial intelligence and computer vision continue to evolve, there are increasingly powerful tools that can be exploited for clinical use. In this study, we present a method for automated detection of ventricular shunt failure implemented via a deep learning semantic segmentation model to detect interval ventriculomegaly. To our knowledge, this is the first study of a fully automated shunt failure detection system. Our initial results suggest that such a method could potentially work with high (> 90%) accuracy in an adult shunted hydrocephalus population.

Upon examination of the perioperative indications for shunt revision, there were two cases of note. In the first (patient #1), the reading radiologist did not feel there was interval ventriculomegaly, but our algorithm felt there was. Interestingly, the treating neurosurgery team at the time had disagreed with the official radiology report and had felt there was interval ventriculomegaly compared to baseline scan (Fig. 3).

Example of relatively subtle interval ventriculomegaly where such an approach could be useful. Of note, in this example the radiology and neurosurgery teams disagreed on the presence of ventriculomegaly. (a) demonstrates axial images of the scan in question compared to (b) baseline scan two days prior. Our algorithm agreed with the treating neurosurgery team that there was evidence of interval ventriculomegaly.

In the other case (patient #13), our algorithm did not call any interval ventriculomegaly, even though the patient did require shunt revision within 7 days. However, when we examined the clinical specifics of this case, we found the patient had undergone shunt revision for an abdominal infection, and thus neither the treating neurosurgery team nor the radiologist at the time felt there was any interval ventriculomegaly. This highlights both the strength of our ability to detect ventriculomegaly (our algorithm thus agreed with the treating neurosurgery team on interval ventriculomegaly 100% of the time), but also the weakness in using ventriculomegaly as the only criteria for shunt failure.

Several previous studies have examined automated ventricular segmentation of clinical images. Quon et al. developed a deep learning semantic segmentation model for ventricular segmentation using pediatric MRI data7. All patients had obstructive hydrocephalus, and they used a two-dimensional U-net model. They were able to achieve an overall Dice score of 0.901, with better prediction in hydrocephalus patients compared to controls (0.946 vs. 0.856). Huff et al. also used a two-dimensional U-net to perform semantic segmentation on a set of normal head CT scans 9. They performed segmentation for each ventricle separately, achieving Dice scores of 0.92, 0.92, and 0.79 on each lateral ventricle and the third ventricle respectively. Automated ventricular segmentation has been performed by others using a variety of other methods as well, with varying degrees of success13,14,15,16,17.

Our work builds upon these earlier achievements in a few ways. First and foremost, our study sought to apply these deep learning techniques towards an actual heuristic for determining shunt failure. We believe this constitutes a step towards an actual clinical implementation of these deep learning methods. In addition, our model was entirely trained and tested on pathologic adult CT scans. Training and testing on this dataset are important because it more closely resembles actual clinical usage. CT scans lack the multimodal imaging information of MRIs, and very frequently are marred by significant artifact from objects such as aneurysm clips and highly dysmorphic ventricles after intracranial bleeds (Fig. 4). Deliberately including these “imperfections” into our training data may have lowered our measured performance for segmentation accuracy, but we felt it was a necessary step to maximize the robustness of the model to similar imperfections in future scans and takes the study closer to actual feasible implementation. Excluding too many of these scans can lead to inflated accuracy scores without addressing the challenges of real-world datasets.

Examples of barriers that need to be overcome for accurate segmentation. Notably, all of these scans are just above the inter-reviewer threshold for inclusion (i.e., Dice score > 0.7 between two human reviewers) and are included in our final training and test sets. Excluded scans have even lower inter-reviewer Dice scores. (a) An intraparenchymal hemorrhage obscuring and distorting portions of both lateral ventricles. (b) Dysmorphic and slit ventricles exacerbate any small differences in accuracy between labeling systems. (c) Cystic changes, dysmorphic ventricles, and infarcted tissue all can blur the borders between parenchyma and ventricle. (d) Streak artifact from an aneurysm clip can make certain axial slices of a scan unusable.

Indeed, the frequency of scan quality problems was investigated in our study, where nearly a third (32.7%) could not be well segmented by human reviewers, who serve as the current gold standard. We found the highest contributing factors were slit ventricles, severe ventricular dysmorphia, and streak artifact. The high rate of these confounding artifacts likely accounted for some of the differences between our Dice scores and those reported in previous literature, which predominantly used more highly-curated datasets. This highlights the challenges of applying computer vision techniques to highly pathologic datasets and the critical importance of robust algorithms for actual clinical use.

The approach we detail here has several advantages. Neural networks are currently thought of as relatively uninterpretable and more of “black-boxes” in their functioning, which leads to reluctance in adopting them in high-stakes decision making like the decision to undergo intracranial surgery. By using changes in ventricular volume as our criteria for shunt failure, our algorithm still allows for human verification and direct human oversight over surgical decision making. If there is a discrepancy, a surgeon can always go back and remeasure the ventricular volume manually. Indeed, manual or computer-assisted volumetrics have shown to aid in shunt failure detection in the past, just without the degree of automation presented here5,18. At the same time, a fully automated system allows for unique uses in workflow, facilitating triage of high-risk scans for closer and more prompt attention19, while also allowing for easy longitudinal and historical tracking of ventricular volumes. Our approach may also have significant applicability in the dialing of programmable shunt valves, where many subsequent CT scans are obtained and changes in ventricular volume may be a variable of particular interest.

Machine learning and computer vision techniques continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Though convolutional neural networks like the one we used in our model remain popular in a wide array of medical computer vision tasks, newer techniques could potentially inform future design. In particular, more efficient object detection frameworks20 and multimodal integration of deep learning techniques21 have the potential to improve upon our approach and could inform the next generation of design. Several obstacles still need to be overcome before such a system could be put into actual clinical use. We cannot stress enough that our study was designed as a feasibility study and proof-of-concept work, and thus sample size was limited. In particular, 13 unique patients in our test set were too few to truly assess the final performance of such an approach, and the 30% volume cutoff that we used in our analysis is a relatively crude one. Future work that includes more data in both the training and testing set would be better able to assess the true efficacy of such an approach in actual practice and fine-tune the parameters. Moreover, as a single-institutional series the generalizability of our results is unknown and future work will require external validation. In addition, the current work is not exclusively focused on the most difficult to diagnose shunt malfunction cases, where arguably human evaluators could benefit most from assistance. These include the many cases where ventricular volume does not change in the setting of shunt malfunction, which would not be picked up by our current approach. Moreover, as mentioned above, a significant number of our scans (32.7%) were excluded before training due to technical factors limiting the human reviewer’s ability to accurately segment the ventricles, and it remains to be seen if computer vision methods would outperform human reviewers on those more challenging images.

Conclusions

In summary, while shunt malfunction remains a commonly encountered problem that can be challenging to diagnose, computer vision-derived algorithms present a potentially fast, consistent, and accurate solution. Here, we trained a convolutional neural network to perform semantic segmentation of the lateral and third ventricles. Our algorithm did not differ significantly from human reviewers in calculating total ventricular volume in non-contrast head CTs of real-life adult hydrocephalus patients. When trialed on a limited sample of actual patients with ventricular shunts, shunt malfunction could be predicted with high accuracy. Though many development challenges remain, it is feasible to create automated algorithms that may detect shunt malfunction in an adult hydrocephalus population.

Data availability

All data utilized in this study is available upon reasonable request to the senior author, Dr. Kevin T. Huang.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Reddy, G. K., Bollam, P. & Caldito, G. Long-term outcomes of ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery in patients with hydrocephalus. World Neurosurg.81, 404–410 (2014).

Patwardhan, R. V. & Nanda, A. Implanted ventricular shunts in the United States: The billion-dollar-a-year cost of hydrocephalus treatment. Neurosurgery56, 144–145 (2005).

Stein, S. C. & Guo, W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr.1, 40–47 (2008).

Toma, A. K., Holl, E., Kitchen, N. D. & Watkins, L. D. Evans’ index revisited: The need for an alternative in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery68, 939–944 (2011).

Yamin, G. et al. Automated CT registration tool improves sensitivity to change in ventricular volume in patients with shunts and drains. Br. J. Radiol.93, 20190398 (2020).

Multani, J. S. et al. Quantitative computed tomography ventriculography for assessment and monitoring of hydrocephalus: A pilot study and description of method in subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg.104, 136–141 (2017).

Quon, J. L. et al. Artificial intelligence for automatic cerebral ventricle segmentation and volume calculation: A clinical tool for the evaluation of pediatric hydrocephalus. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr.27, 131–138 (2020).

Hale, A. T. et al. Machine learning predicts risk of cerebrospinal fluid shunt failure in children: A study from the hydrocephalus clinical research network. Childs Nerv. Syst.37, 1485–1494 (2021).

Huff, T. J., Ludwig, P. E., Salazar, D. & Cramer, J. A. Fully automated intracranial ventricle segmentation on CT with 2D regional convolutional neural network to estimate ventricular volume. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg.14, 1923–1932 (2019).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science 234–241 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

Bossuyt, P. M. et al. STARD 2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ351, h5527 (2015).

Maragkos, G. A. et al. Automated lateral ventricular and cranial vault volume measurements in 13,851 patients using deep learning algorithms. World Neurosurg.148, e363–e373 (2021).

Zhou, X., Ye, Q. & Jiang, Y. Systematic and comprehensive automated ventricle segmentation on ventricle images of the elderly patients: A retrospective study. Front. Aging Neurosci.12 (2020).

Chen, W., Smith, R., Ji, S. Y., Ward, K. R. & Najarian, K. Automated ventricular systems segmentation in brain CT images by combining low-level segmentation and high-level template matching. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak.9 Suppl 1, 1–4 (2009).

Dubost, F. & Nardin, M. Multi-atlas image registration of clinical data with automated quality assessment using ventricle segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 63 (2020).

Klimont, M. et al. Automated ventricular system segmentation in paediatric patients treated for hydrocephalus using deep learning methods. Biomed Res. Int. 3059170 (2019).

Jha, T. R. et al. Prediction of shunt failure facilitated by rapid and accurate volumetric analysis: A single institution’s preliminary experience. Childs Nerv. Syst.38, 1907–1912 (2022).

Titano, J. J. et al. Automated deep-neural-network surveillance of cranial images for acute neurologic events. Nat. Med.24, 1337–1341 (2018).

Chen, S. et al. Identification and detection of biological information on tiny biological targets based on subtle differences. Machines. 10, 996 (2022).

Zhang, N., Sun, Z., Xie, Y., Wu, H. & Li, C. The latest version ChatGPT powered by GPT-4o: what will it bring to the medical field? Int. J. Surg.https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001754 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This project was conceived by Kevin Ted Huang and Omar Arnaout. All authors contributed in significant fashion to data collection, data analysis, manuscript original draft writing, or review and editing of the paper. All authors agree to the content present in this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, K.T., McNulty, J., Hussein, H. et al. Automated ventricular segmentation and shunt failure detection using convolutional neural networks. Sci Rep 14, 22166 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73167-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73167-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Automated Detection of Hydrocephalus in Pediatric Head Computed Tomography Using VGG 16 CNN Deep Learning Architecture and Based Automated Segmentation Workflow for Ventricular Volume Estimation

Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine (2025)

-

Application of deep neural networks in automatized ventriculometry and segmentation of the aqueduct in pediatric hydrocephalus patients

Neuroradiology (2025)