Abstract

Hormone therapy, especially androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), is effective against prostate cancer (PC), whereas long-term ADT is a risk for metabolic/cardiovascular disorders including diabetes (DM), hypertension (HT) and dyslipidemia (DL), and might result in progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). We thus conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study to ask whether CRPC progression would be associated positively with HT, DM or DL and negatively with statins prescribed for treatment of DL. In this study, 1,112 nonmetastatic PC patients undergoing ADT were enrolled. Univariate statistical analyses clearly showed significant association of HT or DM developing after ADT onset, though not preexisting HT or DM, with early CRPC progression. On the other hand, preexisting DL or statin use, but not newly developed DL or started statin prescriptions following ADT, was negatively associated with CRPC progression. Multivariate analysis revealed significant independent association of the newly developed DM or HT, or preexisting statin use with CRPC progression [adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals): 3.85 (1.65–8.98), p = 0.002; 2.75 (1.36–5.59), p = 0.005; 0.25 (0.09–0.72), p = 0.010, respectively]. Together, ADT-related development of HT or DM and preexisting statin use are considered to have positive and negative impact on CRPC progression, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is now one of the major cancers in Japanese males, which is expected to remain constant at least until 20501. Accumulating evidence suggests some acquired risk factors that might affect the onset or unfavorable prognosis of PC, e.g. lifestyle-related ailments including obesity, hypertension (HT) and diabetes mellitus (DM), but not hypertriglyceridemia2,3,4. Nonetheless, there is plenty of conflicting evidence5,6,7,8 that sparks the ongoing debates regarding the association between lifestyle-related diseases and PC. In general, initial treatment options for PC include hormone therapy, particularly androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)9. Over 10–20% patients with PC subjected to ADT eventually tend to develop a resistance known as castration-resistant PC (CRPC) within 5 years of follow-up10,11. Males with metastatic PC appear to have a higher risk of earlier CRPC progression than nonmetastatic PC patients12,13. Cancer cell proliferation in CRPC is associated with overexpression of androgen receptors (ARs), AR mutations involved in ligand-independent constitutive AR activity or promiscuous ligand activation of ARs, intracrine steroidogenesis and acceleration of AR-independent mitogenic signals14,15,16.

Long-term ADT is associated with various adverse events, such as metabolic syndrome including obesity and DM accompanied by cardiovascular diseases, in addition to osteoporosis and sarcopenia17,18,19. A cross sectional clinical study showed that 55% of PC males undergoing long-term (12 months or longer) ADT developed metabolic syndrome, while the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 20% in age-matched PC patients who underwent prostatectomy and/or radiotherapy but not ADT, and 22% in age-matched healthy males, respectively20, essentially in agreement with a report from an independent group21. Some reports also suggest the increased development of HT following ADT22,23, although there exists rebutting evidence20,24. It is emphasized that various clinical studies suggest a molecular link between cardiovascular diseases and prostate cancer/hormone therapy25.

Interestingly, there is evidence that nonmetastatic PC patients with DM receiving ADT progressed to CRPC faster than those without DM3. Most recently, our retrospective study at a single center demonstrated that PC patients who developed DM after the initiation of ADT, but not ones diagnosed as DM before ADT, exhibited significantly earlier progression to CRPC than non-DM PC patients12. In the same study, HT developing after ADT initiation, but not preexisting HT, also tended to be associated with early CRPC progression, but the results were not statistically significant. It is also to be noted that no such association between dyslipidemia (DL) and CRPC progression was detected. Importantly, statins may improve the overall and prostate cancer-specific mortality in PC patients receiving ADT26, so that the prescription of statins might obscure the effect of DL on CRPC progression in the previous study12.

In the present study, we thus conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study, in order to examine the association of hormone therapy-related metabolic/cardiovascular disorders and preexisting or delayed use of statins with the progression from nonmetastatic PC to CRPC.

Methods

Patient selection, data collection, and definition of CRPC

Medical records of patients diagnosed with PC between January 2012 and March 2020 were extracted and collected from Kindai University Nara Hospital, Kansai Medical University Hospital, and Fuchu Hospital. PC patients without distant metastasis who underwent ADT, irrespective of surgical intervention, were enrolled in this study, and their clinical data were analyzed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ADT duration of less than two months, and (2) inadequate or abnormal ADT, such as ADT limited to the preoperative period and interruptions of ADT for six months or longer. Medicines used for ADT in this study were leuprorelin and goserelin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor agonists that desensitize GnRH receptors, and degarelix, a GnRH receptor antagonist. CRPC was defined essentially in accordance with the criteria of the European Urology Association guidelines27, i.e. a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level higher than 2.0 ng/mL and two consecutive increases in PSA levels by at least 50% from the PSA nadir in patients with a castrate level of testosterone (≤ 50 ng/dL). In addition to PC patients who were clearly diagnosed with CRPC by a physician as mentioned above, ones who received second-generation anti-androgen agents, such as abiraterone, apalutamide and enzalutamide, or cytotoxic anticancer drugs, such as docetaxel and cisplatin, were also included in the CRPC category.

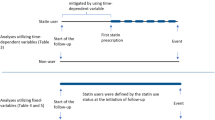

Study design, statistical analyses of clinical data and ethical approval

Nonmetastatic PC patients receiving ADT were classified according to tumor stage (T1–T3), Gleason score (≥ 6, 7, and ≥ 8), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, and risk classification of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (“low” or “intermediate” risk versus “high” risk)28. Preexisting DM, HT, DL and statin use (preDM, preHT, preDL and preStatin, respectively) before and newly developed/started DM, HT, DL and statin use (postDM, postHT, postDL and postStatin, respectively) after ADT initiation in the PC patients were detected by checking physicians’ diagnosis and prescribed medications for treatment of DM, HT and DL in their medical records. CRPC progression in PC patients who had preexisting or newly developed/started DM, HT, DL and statin use were compared with ones who did not have DM, HT, DL and statin use before or after ADT initiation (nonDM, nonHT, nonDL and nonStatin, respectively).

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the difference in the duration of ADT between the patients who did and did not have progression to CRPC. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank test were used to examine the effects of different factors, such as DM, HT, DL and statin use, as well as PSA levels or PC characteristics at initial diagnosis, on the time-related CRPC progression. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated to investigate the correlation between PSA levels and the time to CRPC progression. The association of DM, HT, DL statin use, PSA levels or PC characteristics with CRPC progression was statistically analyzed using univariate and/or multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional hazards model. Explanatory variables included in the multivariate analysis were DM (nonDM, preDM, postDM), HT (nonHT, preHT, postHT), statin use (nonStatin, preStatin, postStatin) and PSA (≥ 13.5 ng/mL), while T Stage, Gleason score and NCCN risk group, known to be closely correlated with PSA values, were not selected as explanatory variables. The hazard ratio (HR) and adjusted HR are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All reported p values were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan)29, a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 3.6.1).

This study was approved by the ethics committees of Kindai University Nara Hospital (Approval No. 620), Kansai Medical University Hospital (Approval No. 2021258), and Fuchu Hospital (Approval No. 20211010), and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the Helsinki Declaration (No. 4934). Due to its retrospective nature, the need for patient consent was waived by the above-mentioned three ethics committees, i.e. Kindai University Nara Hospital Certified Review Board, Kansai Medical University Hospital Research Ethics Review Committee, and The Fuchu Hospital Ethical Committee, which approved the use of the opt-out method with respect to patient consent.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 1,294 PC patients undergoing hormone therapy at the three hospitals in Japan, 1,112 patients with nonmetastatic PC were enrolled in this study (Table 1), according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The median age of the patients was 76 years and the median PSA level at the time of initial diagnosis was 13.5 ng/mL. Of the enrolled 1,112 PC participants, 138 (12.4%) had DM including 110 (9.9%) preDM and 28 (2.5%) postDM, 375 (33.7%) had HT including 298 (26.8%) preHT and 77 (6.9%) postHT, and 219 (19.7%) had DL including 163 (14.7%) preDL and 56 (5.0%) postDL. Of note is that, of the 219 PC patients with DL, statin users were 201 (18.1%) including 151 (13.6%) preStatin and 50 (4.5%) postStatin. The median duration of ADT for all patients was 18.8 months (range 2.10–109), and 74 (6.7%) PC patients developed CRPC during the observation period (Table 1). There was no significant difference (p = 0.0695) in the duration of ADT between patients who did and did not develop CRPC, and the respective median durations of ADT were 24.6 months (range 2.80–80.7) and 18.2 months (range 2.10–109).

Relationship of metabolic/cardiovascular disorders, statin use and initial diagnosis with time to CRPC progression in nonmetastatic PC patients, as assessed by univariate analyses

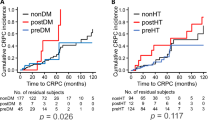

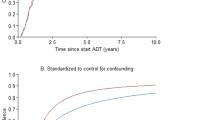

The Kaplan–Meier curves indicated that the postDM, though not preDM, patients exhibited a faster progression to CRPC than the non-DM patients, which was statistically significant, as assessed by the log-rank test (p < 0.001) and the univariate Cox proportional hazard model (HR 4.41; 95% CI, 2.10–9.25; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A), in agreement with our previous report from a single center study12. The present analysis of the data from the three hospitals also showed that the postHT, but not preHT, patients had the clearly accelerated progression to CRPC than non-HT patients, which was statistically significant, as analyzed by the log-rank test (p = 0.001) and the univariate Cox hazard model (HR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.53–5.02; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). This evidence is new and very important, because our previous single-center study failed to detect statistically significant association between CRPC progression and postHT12. Thus, the present study, though the relatively small sample size, showed the association of the development of both metabolic and cardiovascular disorders with CRPC progression. On the other hand, the Kaplan–Meier curves showed that the CRPC progression was not different between postDL and nonDL patient groups, but apparently delayed in preDL patients as compared with nonDL patients, although the log-rank test did not detect statistically significant differences (Fig. 2A). The univariate analysis using the Cox hazard model showed that the risk of CRPC progression was significantly lower in the preDL group (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.12–0.94; p = 0.037) (Fig. 2A). Of 163 preDL patients, 151 (92.6%) received statin medication before and after ADT initiation (see Table 1). The Kaplan–Meier curves depicted a tendency toward the delayed CRPC progression in the preStatin group, which was also supported by the univariate Cox hazard model (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.14–1.03; p = 0.056). Thus, it is likely that preStatin rather than preDL impacted the progression to CRPC in nonmetastatic prostate cancer patients.

Kaplan-Meier curves and statistical analysis for the association of CRPC progression following ADT with DM or HT in nonmetastatic PC patients. DM (A) and HT (B) were separated into preexisting DM and HT at the initial PC diagnosis (preDM and preHT), newly developed DM and HT after ADT initiation (postDM and postHT), and none of them (nonDM and nonHT), respectively. Statistical differences among and between three patient groups were analyzed using the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazard regression model, respectively. The p values from the log-rank test are given above line graphs, and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs and p values from the Cox regression analysis are shown in square boxes.

Kaplan-Meier curves and statistical analysis for the association of CRPC progression following ADT with DL or statin use in nonmetastatic PC patients. DL (A) and statin use (B) were separated into preexisting DL and statin use at initial PC diagnosis (preDL and preStatin), newly developed DL and statin use onset after ADT initiation (postDL and postStatin), and none of them (nonDL and nonStatin), respectively. Statistical differences among and between three patient groups were analyzed using the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazard regression model. The p values from the log-rank test are given above line graphs, and the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs and p values from the Cox regression analysis are shown in square boxes.

The association between the PC characteristics at the initial diagnosis and time to CRPC progression was also ascertained in the present nonmetastatic PC participants. A significant negative correlation was observed between the initial PSA level and the time to progress to CRPC (rs = − 0.249; p = 0.035) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Kaplan-Meier curves and statistical analyses using the log-rank test and univariate Cox hazard model detected significant association of higher initial PSA levels, T-stages and Gleason scores, and also the high-risk group in NCCN guideline with early progression to CRPC (Supplementary Fig. 1B and 2).

Multivariate analysis of the association of postDM/postHT and preStatin with time-related progression to CRPC in nonmetastatic PC patients

To further examine the impact of ADT-related DM and HT, and preexisting statin use on the progression of nonmetastatic PC to CRPC, the data were subjected to Cox proportional multivariate analysis. Factors that were independently and positively correlated with time-related progression to CRPC were: postDM (adjusted HR, 3.85; 95% CI, 1.65–8.98; p = 0.002), postHT (adjusted HR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.36–5.59; p = 0.005) and PSA ≥ 13.5 ng/mL (median) at the initial diagnosis (adjusted HR, 3.49; 95% CI: 1.90–6.39; p < 0.001) (Table 2). On the other hand, preStatin was independently and negatively associated with the progression to CRPC (adjusted HR, 0.25; 95% CI: 0.09–0.72; p = 0.010) (Table 2).

Discussion

This multicenter retrospective cohort study demonstrates that progression to CRPC in patients with nonmetastatic PC is positively associated with postDM and postHT, rather than preDM and preHT, and negatively associated with preStatin. The impact of postDM in the present study is consistent with our previous single center study showing significant association of postDM with CRPC progression in metastatic and nonmetastatic PC patients12. The impact of postHT on the progression to CRPC, as observed in the present multicenter study, was not clearly detected in the previous single center study12. However, it is not clear whether the development of postHT and postDM was really caused by ADT itself. The negative association of preDL, but not postDL, with the progression to CRPC (see Fig. 2A) is considered to reflect the preventive effect of preexisting statin use on CRPC progression (see Fig. 2B), because the majority of PC patients with preexisting DL received statins before and after ADT initiation, i.e. preStatin (see Table 1). Nonetheless, the possibility cannot be ruled out that preDL itself would contribute to the delayed CRPC progression. Further, the present evidence for the association of preStatin, but not postStatin, on the delayed CRPC progression supports the recent studies suggesting that statin use might be beneficial in the early hormone-sensitive phases but not in the advanced hormone-resistant phases30,31. Together, our present study strongly suggests that not only DM but also HT developing after the onset of ADT is a risk factor for progression to CRPC in nonmetastatic PC patients, which can be prevented by preexisting statin use. Thus, there is an urgent need to conduct prospective studies to address the question whether statin therapy starting immediately before ADT onset and after initial PC diagnosis could prevent CRPC progression.

The association of DM or HT with PC has been investigated several times, but no definitive conclusions have been drawn so far2,3,5,6,7,8. Clinical studies demonstrated a correlation between DM and the progression to CRPC in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer3, and an association of increased risk of PC mortality with elevated fasting blood glucose levels following PC diagnosis32. However, these studies did not separately analyze the effects of preexisting DM and newly developed DM following ADT initiation on the disease progression of PC. On the other hand, plenty of studies have reported that long-term ADT leads to type 2 DM in PC patients20,33,34,35, in agreement with the evidence that testosterone maintains the function of β cells36 and insulin sensitivity, and its deficiency is associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 DM37. Some reports have also reported the increased development of cardiovascular disorders including HT following ADT22,23,25,38, in agreement with the evidence that low testosterone levels are predictive of HT39. Collectively, our present findings suggest that ADT-related, but not preexisting, DM and HT are risk factors for early progression to CRPC in nonmetastatic PC patients.

There is evidence that ADT causes DL in PC patients40,41. However, the present multicenter study showed the lack of association between postDL and CRPC progression following ADT, in agreement with our previous single center study12. Nonetheless, significant negative association of preDL and preStatin with CRPC progression was detected in nonmetastatic PC patients (see Fig. 2A; Table 2, respectively). There is evidence that long-term use of statins is associated with a lower risk of PC itself42, and that concurrent statin use with ADT is associated with reduced PC-specific mortality26. Given that most preDL and postDL patients used statins (see Table 1), it is likely that preStatin, rather than preDL, contributed to the delayed CRPC progression, and that postStatin overcame postDL-related, if any, acceleration of CRPC progression.

Molecular mechanisms responsible for the association between the development of DM and HT following ADT initiation and CRPC progression are still open to question. One of the possible molecular candidates that might increase in response to metabolic or cardiovascular disorders and mediate CRPC progression is the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family. Some FGFs including FGF9, FGF15, FGF19, FGF21 and basic FGF (bFGF) have antihyperglycemic, antihyperlipidemic or anti-inflammatory activities, and increases in responses to type 2 DM, obesity, renal dysfunction and ischemic heart diseases43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Interestingly, there is evidence for the involvement of the FGF family including FGF9, FGF19 and bFGF in the growth and/or CRPC progression of PC50,51,52,53,54,55. Signaling through FGF receptors has also been shown to be important for PC cell growth in AR-negative human prostate cancer cells collected from patients with CRPC54,56,57. Therefore, it is possible that FGFs might be key molecules in the interaction between the hormone therapy-related HT/DM and progression to CRPC in nonmetastatic PC patients.

The limitations of the present multicenter study are: (1) it was a retrospective study, (2) the number of patients was still limited, although it was improved from the previous single center analysis12, (3) the lack of detailed patient information including obesity, and (4) the difficulty of separate analysis of the effects of DL and statin use on CRPC progression. Hence, future prospective studies employing a greater number of participants including statin-naïve PC patients with DL should address the unanswered questions in this study.

This multicenter retrospective cohort study demonstrates the positive association of the development of DM and/or HT following ADT with CRPC progression and the negative association of preexisting statin use with CRPC progression in nonmetastatic PC patients. Thus, ADT-related development of HT as well as DM is considered a risk factor for early progression to CRPC, and the preexisting statin use and possibly initiation of statin prescription before ADT might be beneficial to delay CRPC progression.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available to protect patients’ privacy but are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Nguyen, P. T., Saito, E. & Katanoda, K. Long-term projections of cancer incidence and mortality in japan and decomposition analysis of changes in cancer burden, 2020–2054: an empirical validation approach. Cancers14 (2022).

Dickerman, B. A. et al. Midlife metabolic factors and prostate cancer risk in later life. Int. J. Cancer. 142, 1166–1173 (2018).

Shevach, J. et al. Concurrent diabetes mellitus may negatively influence clinical progression and response to Androgen Deprivation Therapy in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Front. Oncol.5, 129 (2015).

Ma, C. et al. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus increases the risk of deaths and castration-resistance in locally advanced prostate cancer patients. Cancer Invest.41, 345–353 (2023).

Suarez Arbelaez, M. C. et al. Association between body mass index, metabolic syndrome and common urologic conditions: a cross-sectional study using a large multi-institutional database from the United States. Ann. Med.55, 2197293 (2023).

Shiota, M. et al. Prognostic significance of antihypertensive agents in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol.37, 813 e821–813e826 (2019).

Monroy-Iglesias, M. J. et al. Metabolic syndrome biomarkers and prostate cancer risk in the UK Biobank. Int. J. Cancer. 148, 825–834 (2021).

Dickerman, B. & Mucci, L. Metabolic factors and prostate cancer risk. Clin. Chem.65, 42–44 (2019).

Schaeffer, E. et al. NCCN guidelines insights: prostate cancer, Version 1.2021. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw.19, 134–143 (2021).

Denmeade, S. R., Sena, L. A., Wang, H., Antonarakis, E. S. & Markowski, M. C. Bipolar androgen therapy followed by androgen receptor inhibition as sequential therapy for prostate cancer. Oncologist. 28, 465–473 (2023).

Kirby, M., Hirst, C. & Crawford, E. D. Characterising the castration-resistant prostate cancer population: a systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract.65, 1180–1192 (2011).

Hayashi, T., Miyamoto, T., Nagai, N. & Kawabata, A. Development of diabetes mellitus following hormone therapy in prostate cancer patients is associated with early progression to castration resistance. Sci. Rep.11, 17157 (2021).

Tamada, S. et al. Time to progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer after commencing combined androgen blockade for advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 9, 36966–36974 (2018).

Recouvreux, M. V. et al. Androgen receptor regulation of local growth hormone in prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology. 158, 2255–2268 (2017).

Mukherjee, R. et al. Upregulation of MAPK pathway is associated with survival in castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 104, 1920–1928 (2011).

Rebello, R. J. et al. Prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 9 (2021).

Fui, M. N. T. & Grossmann, M. Hypogonadism from androgen deprivation therapy in identical twins. Lancet. 388, 2653 (2016).

Corona, G. et al. Cardiovascular risks of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate Cancer. World J. Mens Health. 39, 429–443 (2021).

Mitsuzuka, K. & Arai, Y. Metabolic changes in patients with prostate cancer during androgen deprivation therapy. Int. J. Urol.25, 45–53 (2018).

Braga-Basaria, M. et al. Metabolic syndrome in men with prostate cancer undergoing long-term androgen-deprivation therapy. J. Clin. Oncol.24, 3979–3983 (2006).

Bosco, C., Crawley, D., Adolfsson, J., Rudman, S. & Van Hemelrijck, M. Quantifying the evidence for the risk of metabolic syndrome and its components following androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 10, e0117344 (2015).

Wu, Y. H. et al. Risk of developing hypertension after hormone therapy for prostate cancer: a nationwide propensity score-matched longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm.42, 1433–1439 (2020).

Swaby, J. et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with metabolic disease in prostate cancer patients: an updated meta-analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 21, e182–e189 (2023).

Smith, M. R. et al. Metabolic changes during gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy for prostate cancer: differences from the classic metabolic syndrome. Cancer. 112, 2188–2194 (2008).

Kakkat, S. et al. Cardiovascular Complications in Patients with Prostate Cancer: Potential Molecular Connections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 242023).

Jayalath, V. H. et al. Statin use and survival among men receiving androgen-ablative therapies for advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open.5, e2242676 (2022).

Heidenreich, A. et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol.65, 467–479 (2014).

Mohler, J. L. et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw.17, 479–505 (2019).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl.48, 452–458 (2013).

Lee, Y. H. A. et al. Statin use and mortality risk in Asian patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: a population-based cohort study. Cancer Med.132023).

Peltomaa, A. I. et al. Statin use and outcomes of oncological treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci. Rep.13, 18866 (2023).

Murtola, T. J. et al. Blood glucose, glucose balance, and disease-specific survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the Finnish randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.22, 453–460 (2019).

Basaria, S., Muller, D. C., Carducci, M. A., Egan, J. & Dobs, A. S. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in men with prostate carcinoma who receive androgen-deprivation therapy. Cancer. 106, 581–588 (2006).

Jhan, J. H. et al. New-onset diabetes after androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a nationwide propensity score-matched four-year longitudinal cohort study. J. Diabetes Complications. 32, 688–692 (2018).

Xu, W. et al. Androgen receptor-deficient islet beta-cells exhibit alteration in genetic markers of insulin secretion and inflammation. A transcriptome analysis in the male mouse. J. Diabetes Complications. 31, 787–795 (2017).

Navarro, G. et al. Extranuclear actions of the androgen receptor enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the male. Cell. Metab.23, 837–851 (2016).

Kelly, D. M. & Jones, T. H. Testosterone: a metabolic hormone in health and disease. J. Endocrinol.217, R25–45 (2013).

Hupe, M. C. et al. Retrospective analysis of patients with prostate cancer initiating GnRH Agonists/Antagonists therapy using a German claims database: epidemiological and patient outcomes. Front. Oncol.8, 543 (2018).

Torkler, S. et al. Inverse association between total testosterone concentrations, incident hypertension and blood pressure. Aging Male. 14, 176–182 (2011).

Smith, M. R. et al. Changes in body composition during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.87, 599–603 (2002).

Gupta, D., Salmane, C., Slovin, S. & Steingart, R. M. Cardiovascular complications of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med.19, 61 (2017).

Xu, M. Y. et al. Association of Statin Use with the Risk of Incident Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Oncol. 7827821 (2022). (2022).

Woo, Y. C., Xu, A., Wang, Y. & Lam, K. S. Fibroblast growth factor 21 as an emerging metabolic regulator: clinical perspectives. Clin. Endocrinol.. 78, 489–496 (2013).

Iglesias, P., Selgas, R., Romero, S. & Diez, J. J. Biological role, clinical significance, and therapeutic possibilities of the recently discovered metabolic hormone fibroblastic growth factor 21. Eur. J. Endocrinol.167, 301–309 (2012).

Chavez, A. O. et al. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-21 is elevated in impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes and correlates with muscle and hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 32, 1542–1546 (2009).

Zhang, C. Y. & Yang, M. Roles of fibroblast growth factors in the treatment of diabetes. World J. Diabetes. 15, 392–402 (2024).

Liu, J. J., Foo, J. P., Liu, S. & Lim, S. C. The role of fibroblast growth factor 21 in diabetes and its complications: a review from clinical perspective. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.108, 382–389 (2015).

Jin, L., Yang, R., Geng, L. & Xu, A. Fibroblast growth factor-based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of obesity-related metabolic complications. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol.63, 359–382 (2023).

Singla, D. K., Singla, R. D., Abdelli, L. S. & Glass, C. Fibroblast growth factor-9 enhances M2 macrophage differentiation and attenuates adverse cardiac remodeling in the infarcted diabetic heart. PLoS ONE. 10, e0120739 (2015).

Teishima, J. et al. Relationship between the localization of fibroblast growth factor 9 in prostate cancer cells and postoperative recurrence. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.15, 8–14 (2012).

Teishima, J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor family in the progression of prostate cancer. J. Clin. Med.8, 183 (2019).

Tuomela, J. & Harkonen, P. Tumor models for prostate cancer exemplified by fibroblast growth factor 8-induced tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Reprod. Biol.14, 16–24 (2014).

Feng, S., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Creighton, C. J. & Ittmann, M. FGF23 promotes prostate cancer progression. Oncotarget. 6, 17291–17301 (2015).

Bluemn, E. G. et al. Androgen receptor pathway-independent prostate cancer is sustained through FGF signaling. Cancer Cell.32, 474–489e476 (2017).

Saylor, P. J. et al. Changes in biomarkers of inflammation and angiogenesis during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Oncologist. 17, 212–219 (2012).

Li, Z. G. et al. Androgen receptor-negative human prostate cancer cells induce osteogenesis in mice through FGF9-mediated mechanisms. J. Clin. Invest.118, 2697–2710 (2008).

Labrecque, M. P. et al. Targeting the fibroblast growth factor pathway in molecular subtypes of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 84, 100–110 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H., A.K.; Data curation, T.H.; Formal analysis, T.H., T.M., S.I.; Investigation, T.H., T.M., S.I., A.K.; Methodology, T.H., T.M., S.I., A.K.; Project administration, T.H., A.K.; Writing-original draft, T.H., A.K.; Writing-review & editing, T.H., T.M., S.I., M.F., K.U., Y.K., A.H., H.K., A.K.; Supervision, A.K. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Atsufumi Kawabata.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, T., Miyamoto, T., Iwane, S. et al. Opposing impact of hypertension/diabetes following hormone therapy initiation and preexisting statins on castration resistant progression of nonmetastatic prostate cancer: a multicenter study. Sci Rep 14, 23119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73197-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73197-y