Abstract

C-C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) plays a crucial role in the advancement of human cancer. Nevertheless, little is known about the multi-omics characterisation of CCL5 and its significance for the immune microenvironment and prognosis of tumor patients. The basal expression levels of the CCL5 gene in normal human tissues, aberrant expression in disease, genomic alterations, prognostic roles, pathway enrichment, immune microenvironment, association with immune checkpoints, drug sensitivity, and the ability to predict patients’ immunotherapeutic response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and small molecule drugs were all thoroughly analyzed using data gathered from 33 cancers. Lastly, we were able to validate CCL5’s involvement in renal clear cell carcinoma by experimental means. We discovered that CCL5 has distinct expression patterns and a diagnostic biomarker significance in cancer. Furthermore, we discovered that CCL5 is essential for both the tumor microenvironment and pan-cancer. TMB and MSI are two frequent immunological checkpoints that are significantly correlated with CCL5, and patients who express high levels of CCL5 have stronger immunotherapeutic response and a better prognosis after immunotherapy. Eventually, molecular docking was used to find small molecule inhibitors that can specifically target CCL5. Ultimately, it was shown that CCL5 knockdown impeded renal clear cell carcinoma cells’ ability to proliferate and invade. Our findings demonstrate the significant potential of CCL5 as an immunotherapeutic response biomarker and prognostic indicator, which may pave the way for more studies on the mechanism of tumor infiltration and CCL5’s potential therapeutic applications in cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer patient survival has improved due to advances in cancer treatment options over the past two decades1,2. It is now recognized that the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays an important role in human cancer development and treatment3,4,5. In the TME, cancer cells often modulate the normal environment of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, limiting the immune response thereby favoring tumor progression as well as hindering cancer therapy6,7. It has become clear that the tumor microenvironment is an important factor influencing the success of immunotherapy8,9. Therefore exploring the role of new immunotherapeutic biomarkers in the tumor microenvironment could help develop more effective immunotherapy regimens for cancer patients and achieve a durable immunotherapy response.

C-C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) belongs to the chemokine system and plays an important role in inflammation and immune response. The correlation between chemokines and their receptors is mixed, with many receptors recognizing more than one ligand and multiple ligands activating several receptors10,11,12. CCL5 acts as an inflammatory chemokine that controls immune cell migration and recruitment in basal and inflammatory environments. In addition, since the receptor for CCL5 is expressed on other types, CCL5 has other roles, such as tumorigenesis, antigen presentation, pathogen elimination, and angiogenesis13. However, there are few studies on CCL5 as a cancer diagnostic and prognostic biomarker and as a predictive marker for cancer immunotherapy.

In this study, we based on TCGA and GTEx RNA-seq datasets to reveal the differential expression of CCL5 in human pan-cancer and normal tissues. We used Kaplan-Meier curves and one-way Cox regression to ascertain the predictive significance of CCL5 in a range of cancer types. To identify the pathways linked to CCL5 expression that are cancer flag markers, hallmark gene set enrichment analysis was used. We demonstrated the relationship between CCL5 and immune cell infiltration using a variety of software programs and single-cell sequencing data. Additionally, using immunological checkpoints and datasets treated with immune checkpoint blocking (ICI), we examine the prognostic function of CCL5 in the immunotherapy response. Ultimately, molecular docking was used to identify putative small molecule inhibitors that may specifically target CCL5. In summary, CCL5 is a potential target for cancer therapy and a prognostic and predictive biomarker of the impact of ICI treatment.

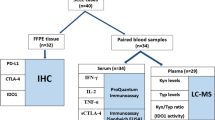

Materials and methods

Data sources

Data from a total of 11,093 normal and tumor tissue samples of 33 cancer types were downloaded from the TCGA database (http://xena.ucsc.edu/), including transcript expression and clinical information14. Differential expression of CCL5 in pan-cancer and normal tissues was analyzed by TIMER database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer) and GEPIA database (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index). Protein expression of CCL5 in pan-cancer Data were obtained from the CPTAC database (https://pdc.cancer.gov/pdc/). We also collected immune checkpoint blockade therapy datasets IMvigor 210 and GSE100797.

Genomic alterations of CCL5 in human cancers

cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/) is a research multifunctional cancer genomics database that analyzes genetic alterations in cancer tissues and understands their genetics, gene expression, epigenetics, and proteome. We analyzed genomic alterations of CCL5 in pan-cancer, including mutations, structural variants, amplifications and deep deletions through the cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/).

Prognostic analysis

Prognosis-related information including overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and disease-specific survival (DSS) of pan-cancer patients was downloaded from the UCSC Xena database. The prognostic role of CCL5 in each cancer was then assessed by one-way Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves.

Functional enrichment analysis

We downloaded the marker gene set from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) and calculated the normalized enrichment score (NES) and p-value of CCL5 for each biological process in each cancer type.

Single-cell analysis and immune infiltration analysis

We performed single-cell analysis by the Tumor Immunity Single Cell Center (TISCH) (http://tisch.comp-genomics.org/home/). CCL5 expression in various immune cell types was quantified and visualized by heatmaps, scatter plots. The Tumor Immunity Estimation Resource (TIMER) database (https://cistrome.org) allowed quantification of the level of immune cell infiltration in tumors by different software analyses, and correlation between mRNA expression of CCL5 and 21 immune cell types was analyzed by Spearman correlation.

Drug sensitivity analysis

The CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/) collects data on the molecular expression of 60 different human cancer cell lines with 100,000 compounds and natural products. The association between CCL5 expression and drug sensitivity was investigated by CellMiner, GDSC and CTRP databases.

Immunotherapy response prediction

We calculate associations between CCL5 and common immunotherapy biomarkers including tumor mutational load (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and common immune checkpoint genes by Spearman correlation analysis. IMvigor 210 dataset to study the treatment outcome of patients with advanced uroepithelial carcinoma treated with anti-PD-L1.GSE100797 GSE100797 dataset investigating the clinical benefit of ACT in melanoma. Patients were divided into low and high CCL5 expression groups by the R package “survminer” to find the optimal cutoff value, and the role of CCL5 in immunotherapy was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival curves and proportional histograms.

Molecular docking

We retrieved FDA-approved small molecule medicines from the zinc15 database and gathered the CCL5 protein structures from the PDB database. Next, using MOE software, we carried out protein-small molecule docking. At a pH of 7 and a temperature of 300 K, the protein’s protonation state and hydrogen bonding orientation were tuned throughout the docking process. After energy reduction, the small molecules were transformed into three-dimensional structures, and docking was used to replicate CCL5’s binding mechanism with small-molecule medications.

Cell culture and transfection

We purchased and used human renal clear cell carcinoma cell lines 769-P and 786-O from the Shanghai Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. 769-P and 786-O cells were cultured in medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum against the wall. Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The Cells at 60% confluency were transfected with siRNA of CCL5 and the negative control obtained from Suzhou Genepharma Co., Ltd(China)by Lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Western blot assay was used to determine siRNA knockdown efficiency. The sequences of siRNA are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent, cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix kit (Takara Bio, China). The PCR panel was obtained using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara Bio, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The qRT-PCR primers are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

CCK8 and plate cloning experiments

Following digestion, counting, and preparation into a cell suspension, each well of a 96-well cell culture plate received a dose of the cell suspension. The 96-well cell culture plate was incubated for 48 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After staining the plate with CCK-8, CCK-8 was added to each well, and the plate was left in the incubator for another two hours. The wells were then gently mixed in a shaker, the entry was measured at 450 nm, and an enzyme labeling instrument was used to read the OD value of each well. After trypan blue dye staining, count the live cells; do a gradient dilution of the single-cell suspension; observe clone development if necessary; fix the fixed solution with methanol; stain the floating color with Giemsa; wash it off; let it air dry; take a picture; and count.

Transwell experiment

Place the chamber inside the culture plate, fill the upper chamber with the heated serum-free medium, let it sit for 15 to 30 min at room temperature, then transfer the cell suspension to the Transwell chamber. In the 24-well subplate chamber, add the medium containing chemokine or FBS to culture the cells. Staining and cell counting were carried out 48 h after the regular culture process.

Wound healing assay

Mark marks the bottom of the six-hole plate with three horizontal lines. Draw two vertical lines perpendicular to the designated line and the orifice plate after comparing the fullness of the cells using a ruler. Using a microscope as a control, take photographs at various periods after cleaning, adding liquid, and scratching. It was raised at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2. The cells were removed after 48 h, and the scratch breadth in the same location was measured, captured on camera, and examined.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare two or more groups, and prognostic curves were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier technique. Pearson’s analysis was used to examine correlations. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. The results of each experiment were repeated three times. R software is available on the official website in 2023.

Results

Aberrant expression of CCL5 in cancer tissues

We integrated the TIMER and GEPIA databases for differences in mRNA expression levels of CCL5 in pan-cancer and normal tissues, and found that CCL5 was significantly highly expressed in 10 tumors, including BRCA, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, KIRC, KIRP, LAML, OV, SKCM, and TGCT. whereas, it was significantly decreased in 8 tumors, including COAD, LUAD, LUSC, PAAD, PRAD, READ, THCA and THYM (Fig. 1A, B). We also analyzed the average mRNA expression of CCL5 in each tumor and normal tissues based on TCGA and GTEx databases. cCL5 was expressed at higher levels in DLBC, TGCT and KIRC and lower in LGG, PCPG and ACC. cCL5 was expressed at higher levels in normal spleen, small intestine and lung and lower in skeletal muscle, brain and testis (Figure S1A). We then analyzed the genetic alterations of CCL5 and found that deep deletions of CCL5 in pan-carcinomas were most frequent in adrenocortical carcinomas and the genomic amplification was highest in cholangiocarcinomas (Figure S1B). Finally, we also analyzed the changes in protein expression levels of CCL5 in pan-cancer and found that CCL5 protein expression levels were significantly increased in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and glioblastoma multiforme, and decreased in breast, lung adenocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 1C).

Aberrant expression of CCL5. (A,B) Differences in mRNA expression levels of CCL5 in tumor and normal tissues. (C) Differences in protein expression levels of CCL5 in breast cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, glioblastoma multiforme and hepatocellular carcinoma.

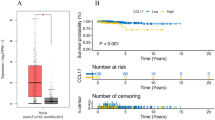

Prognostic analysis of CCL5 in pan-cancer

To assess the prognostic value of CCL5 in various cancer types, we performed uniCox regression analysis. For OS analysis, CCL5 acted as a risk factor in 6 cancer types, including GBM, KIRC, LAML, LGG, THYM, and UVM. whereas it acted as a protective factor in 7 other cancers, including BRCA, CESC, DLBC, HNSC, SARC, SKCM, and UVM (Fig. 2A). We then performed Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of CCL5 in the above cancers, which showed that CCL5 had survival difference analysis in 11 cancer types (Fig. 2B). We further performed DFS, PFS and DSS, and the results all showed that CCL5 played a protective factor in endometrial cancer (UCEC) (Fig. 2C-E), suggesting that our CCL5 plays an important role in the prognosis of patients with UCEC and has the potential to be used as a prognostic biomarker.

Prognostic analysis. (A) Forest plot of overall survival (OS) of CCL5 in pan-cancer by uniCox analysis. (B) UniCox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves analyzing the survival status of patients with high expression of CCL5 and low expression of CCL5 were significant. (C–E) Forest plot analyzing disease-free survival (DFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) of CCL5 in pan-cancer by uniCox regression.

Functional enrichment analysis of CCL5

To understand the biological processes of CCL5 in various cancers, we performed GSEA enrichment analysis of it in pan-cancer. The results showed that CCL5 was significantly enriched and positively correlated in immune-related pathways, including allograft rejection pathway, IL2/STAT5, IL6/JAK/STAT3, inflammatory response, IFN-α response, IFN-γ response and TNFA-signaling-via-NFKB. This suggests that our CCL5 may be closely associated with the tumor immune cell microenvironment and immune checkpoints. In addition, CCL5 was significantly enriched during tumor EMT, which was significantly positively correlated with ACC, BLCA, COAD, GBM, KIRP, LAML, LGG, LIHC, OV, PAAD, PCPG, PRAD, READ, STAD, THCA, UCS, and UCM, and significantly negatively correlated with TGCT, suggesting that CCL5 might play an important role in play an important role in tumor migration and invasion (Fig. 3).

Single-cell data analysis

To further understand which immune cells express CCL5 in the tumor microenvironment, we performed single-cell analysis of CCL5 on single-cell data. The results showed that CCL5 was significantly associated with immune-infiltrating cells, in which it was mainly highly expressed in CD8 + T cells, depleted CD8 + T cells and NK cells, suggesting that CCL5 plays an anti-tumor role in the immune response. In the GSE146771 colorectal cancer (CRC) dataset, CCL5 was broadly expressed with a variety of immune cell types, of which it was highly expressed mainly in CD8 + T cells, depleted CD8 + T cells and NK cells (Fig. 4). In the GSE102130 glioma dataset, CCL5 was highly expressed in monocytes/macrophages and malignant tumor cells. In addition, in the GSE118056 Markel cell carcinoma (MCC) dataset, CCL5 was highly expressed in myofibroblasts in addition to CD8 + T cells, depleted CD8 + T cells and NK cells.

Analysis of immune cell infiltration

To further investigate the relationship between CCL5 and the immune microenvironment, we analyzed the correlation between CCL5 expression and the infiltration of 19 types of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, including B cells, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, regulatory T cells, T follicular helper cells, and γδ T cells, by means of several software, mast cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, monocyte progenitors, Endo, eosinophils, hepatic stellate cells, lymphoid progenitors, NK T cells and myeloid progenitors. The results showed that in most tumors, CCL5 was positively correlated with the level of CD8 + T cell, B cell, dendritic cell, and macrophage infiltration, and negatively correlated with the level of myeloid progenitor cell infiltration (Fig. 5). Subsequently, we performed Spearman’s correlation analysis of CCL5 expression with common immunomodulatory genes and found that CCL5 was significantly positively correlated with immunosuppressive genes, immunostimulatory genes, MHC molecular receptors, cytokines and receptors in pan-cancer (Figure S2). The above results suggest that CCL5 may play a key role in the tumor immune microenvironment and influence cancer development and treatment by affecting immune cells or immunomodulatory genes.

CCL5 correlates with immune infiltrating cells. CCL5 was analyzed using TIMER, EPIC, QUANTISEQ, XCELL, MCPCOUNTER, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT-ABS and XCELL software to correlate CCL5 with B cells, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, regulatory T cells, T follicular helper cells, γδ T cells, mast cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, monocyte progenitors, Endo, eosinophils, hepatic stellate cells, lymphoid progenitors, NK T cells, and myeloid progenitors.

Predictive role of CCL5 in immunotherapy and chemotherapy

Major breakthroughs in cancer therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer treatment15. We first assessed the association between CCL5 in pan-cancer and two common immunotherapy predictors, including tumor mutational load (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI). TMB and MSI are highly correlated with the immunotherapy response of tumor patients, with tumors high in TMB or MSI generating more neoantigens and eliciting stronger T-cell responses and anti-tumor responses16. The results showed that CCL5 was significantly positively correlated with the TMB of BLCA, BRCA, COAD, LGG, THYM, and UCEC, while it was significantly negatively correlated with the TMB of CHOL, HNSC, KIRP, PAAD, PRAD, TGCT, and THCA (Fig. 6A). For MSI analysis in pan-cancer, CCL5 was positively correlated with MSI in COAD, THCA and UCEC, and negatively correlated in ESCA, KIRP, LIHC, LUSC, OV, SARC and TGCT (Fig. 6B). The above results suggest that CCL5 may predict immunotherapy response in cancer.

CCL5 in immunotherapy and chemotherapy. relationship between CCL5 expression and tumor mutational load (A) and microsatellite instability (B). kaplan-Meier curves of patients with high versus low expression of CCL5 in uroepithelial carcinoma in the IMvigor 210 cohort (C), and CCL5 expression between the anti-PD-L1 treatment response group and the non-response group (D). Kaplan-Meier curves of patients with high versus low expression of CCL5 in the GSE100797 cohort with melanoma (E), and differences in CCL5 expression between ACT treatment response and non-response groups (F). (G) Correlation of CCL5 with chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity. correlation of CCL5 with drug sensitivity in GDSC (H) and CTRP (I) databases.

We further came in the immunotherapy dataset to validate the predictive role of CCL5 on immunotherapy response. First in the IMvigor 210 dataset, patients with uroepithelial cancer with high CCL5 expression had a prognosis due to low expression (Fig. 6C). In addition, CCL5 expression levels were significantly higher in patients with urothelial carcinoma responding to anti-PD-L1 therapy than in the non-responder group (Fig. 6D). Similar results were then obtained by analyzing the GSE100797 dataset. the group of melanoma patients with high CCL5 expression and receiving ACT had a better prognosis (Fig. 6E). Similarly for the ACT-responsive group of melanoma patients the CCL5 expression level was significantly higher (Fig. 6F). These data suggest the potential clinical value of CCL5 in immunotherapy response.

To further investigate the association between CCL5 and chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity, we first analyzed the relationship between CCL5 and drug sensitivity from the cellMiner database, where positive correlation indicates that stronger gene expression is more sensitive to drugs, while negative correlation indicates that stronger gene expression is more resistant to drugs, e.g., the stronger the expression of CCL5, the more sensitive the patients were to Pazopanib and Isotretinoin the more sensitive (Fig. 6G). In addition, the GDSC and CTRP databases were utilized to analyze the relationship between mRNA expression used to construct drug sensitivity and CCL5. Contrary to the cellMiner database, a positive correlation indicated that gene expression was associated with drug resistance, whereas a negative correlation indicated that gene expression was associated with drug sensitivity, and CCL5 was found to be significantly associated with most chemotherapeutic drug sensitivities (Fig. 6H-I).

Molecular docking

Research has shown that CCL5 has a significant influence on the advancement of cancer by directly impacting tumors, stifling T cell reactions, and stimulating angiogenesis. Consequently, CCL5 or its receptor focused inhibition may lessen tumor angiogenesis and aid in the therapy of cancer metastasis17. In order to replicate the binding pattern of small molecule medications to CCL5, we also gathered CCL5 and 1379 FDA-approved and certified small molecule pharmaceuticals in MOE utilizing molecular docking. The top eight small molecule medications with the greatest affinity to CCL5 is gadofosveset (-8.0563), Dfo (-7.9033), Tessalon (-7.8265), Atazanavir(-7.6238), Chlorhexidine (-7.5844), and Norvir (-7.5528) (Fig. 7A-H). For instance, Lys-56 and Arg-59, two amino acid residues that both function as hydrogen bond donors, combine with nonoxynol-9 to generate hydrogen bonds.

Molecular docking poses of CCL5 with small molecule drugs. Docking poses of the top eight small molecules with the highest affinity for the active pocket of CCL5, Nonoxynol-9 (A), Gadofosveset (B), Dfo (C), Trypan Blue (D), Tessalon (E), Atazanavir (F), Chlorhexidine (G), and Norvir (H). The images were generated by MOE software(https://www.chemcomp.com/Products.htm).

Knockdown of CCL5 inhibits the proliferation and migration of renal clear cell carcinoma cells

In order to study the function of CCL5 in renal clear cell carcinoma, we created siRNA for CCL5, which we used to suppress the expression of CCL5 in human renal clear cell carcinoma cell lines 769-P and 786-O cells. QPCR was used to identify the CCL5 silencing effect, and it was shown that si-CCL5 could successfully suppress CCL5 expression (Fig. 8A). 769-P and 786-O cells transfected with si-CCL5, respectively, were used for CCK8, plate cloning, Transwell, and wound-healing studies. The proliferation capacity of 769-P and 786-O cells in the si-CCL5 group was much less than that of the NC group at 24, 48, and 72 h, according to the findings of CCK8 studies (Fig. 8B-C). The plate cloning experiment findings similarly showed that 769-P and 786-O cells’ capacity to proliferate after CCL5 knockdown was noticeably less than that of the NC group (Fig. 8D-E).The transwell experiment demonstrated that 769-P and 786-O cells’ capacity for cell migration was greatly diminished after CCL5 knockdown (Fig. 8F-G).The migratory capacity of 769-P and 786-O cells in the si-CCL5 group was considerably lower than that of the NC group 48 h later, according to the wound-healing experiment (Fig. 8H-I).

Knockdown of CCL5 inhibited the proliferation and migration ability of renal clear cell carcinoma cells. (A) QPCR verified the mRNA expression level of CCL5 in 769-P and 786-O cells after transfection with siRNA. CCK8 viability assay (B,C), plate cloning assay (D,E), transwell cell migration ability (F,G) and Wound-healing assay (H,I) in 769-P and 786-O cells after transfection with si-CCL5. Note *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

A growing body of research has shown the clinical significance and pivotal involvement of CCL5 in cancer18. By using multi-omics and pan-cancer data, we thoroughly examined the basal expression levels of the CCL5 gene in normal human tissues as well as abnormal expression in cancer, genomic alterations, diagnostic and prognostic roles, correlation with pathways related to cancer, associations with the immune microenvironment and immune checkpoints, and prediction of patients’ immunotherapeutic responses to ICIs and targeted small molecule drugs. We discovered that the amounts of CCL5 protein and gene expression are unique to different forms of cancer. For instance, glioblastoma, lung adenocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma all had significantly lower levels of CCL5 protein expression than normal tissues, while renal clear cell carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and glioblastoma all had significantly higher levels than normal tissues. Moreover, a prognostic analysis conducted using the TCGA database demonstrated a significant correlation between the CCL5 gene and the prognosis of patients with the majority of cancers, including BRCA, CESC, DLBC, GBM, HNSC, KIRC, LAML, LGG, SARC, SKCM, THYM, UCEC, and UVM. These results suggest that the CCL5 gene may have utility as a prognostic biomarker. Using single-cell sequencing data and other techniques for evaluating the level of immune infiltration, we further examined the function of CCL5 in cancer development and the tumor microenvironment. We discovered that CCL5 was strongly expressed in CD8 + T cells and NK cells. The strong association found between CCL5 and immunological checkpoints suggests that CCL5 has considerable research potential in the field of immunotherapy. In order to identify small molecule medications that can target CCL5, we lastly carried out molecular docking against CCL5.

The majority of inflammatory cells are capable of expressing CCL5, with T cells and monocytes being the most often found cell types to do so. CCL5 has the strongest affinity for CCR5, even though it may also bind to CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CCR519. In recent years, the CCL5/CCR5 axis has been extensively studied in the tumorigenesis of many types of cancers, such as head and neck cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, chondrosarcoma, breast cancer, etc20. The goal of the CCL5/CCR5 axis has always been to improve the milieu that supports the survival of tumor cells. On the one hand, CCL5/CCR5 causes cellular signaling via ERK/MEK, PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, and HIF-α to give tumor cells the ability to proliferate uncontrollably and become immortal20. In contrast, these signaling pathways eliminate obstacles to tumor invasion and metastasis by controlling MMP, growth factors, and inflammatory factors21. In addition, CCL5/CCR5 recruits Tregs, MDSCs and TAM to induce tumor immunosuppression22.

We further explored the role of CCL5 in therapeutic aspects through single-cell data, immunotherapy datasets and molecular docking. We found that CCL5 is strongly expressed in CD8 + T cells and NK cells. the close association between CCL5 and immune checkpoints suggests that CCL5 has considerable research potential in the field of immunotherapy. In order to find small molecule drugs that can target CCL5, we finally performed molecular docking against CCL5. Eight of the top small molecules with the strongest affinity for CCL5 are in clinical trials, including Gadofosveset, which is being studied extensively for its potential use as a contrast agent in the cardiovascular system23.Tessalon can act as a local anesthetic in the peripheral nerves, with both sensory and motor nerve blocking effects24. Atazanavir as an antiretroviral therapy is now widely studied in clinical trials in human immunodeficiency diseases25. Chlorhexidine has an important role in preventing surgical infections26.

The results of this study show that CCL5 has potential as a therapeutic target, biomarker for prognosis and diagnosis, and other uses. Nevertheless, our study does have a few drawbacks. Firstly, there were various biases, including as the study’s retrospective character, its small sample size, and its mixed utilization of tumor specimens that had undergone or had not undergone preoperative treatment. Further validation of our findings’ accuracy requires the collection and evaluation of a large cohort of clinical cases. To conclude, additional in vitro and in vivo investigations will be conducted in future studies to confirm the role of the CCL5 gene in cancer. This will help to comprehensively identify the mechanism by which members of the CCL5 gene might be used as cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Conclusion

In this investigation, we looked at CCL5’s biomarker value and variations in expression in cancer. It was also discovered that CCL5 and the tumor microenvironment are important in pan-cancer. Immunotherapy and common chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity are closely linked to CCL5. Through molecular docking, small molecule inhibitors capable of targeting CCL5 were discovered. Ultimately, it was discovered through experimentation that CCL5 gene expression knockdown impeded renal clear cell carcinoma cell growth and invasion. This study offers a new target for cancer medication therapy by comprehensively analyzing the role and viability of CCL5 as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target using multi-omics.

Data availability

All data utilized in this study are included in this article and all data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. Cancer J. Clin.71(1), 7–33 (2021).

Xu, Y., Li, Q. & Lin, H. Bioinformatics analysis of CMTM family in pan-cancer and preliminary exploration of CMTM6 in bladder cancer. Cell. Signal.115, 111012 (2024).

Bader, J. E., Voss, K. & Rathmell, J. C. Targeting metabolism to improve the tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cell. 78(6), 1019–1033 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 9(1), 132 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Identification of PANoptosis-related signature reveals immune infiltration characteristics and immunotherapy responses for renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 24(1), 292 (2024).

Nagarsheth, N., Wicha, M. S. & Zou, W. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol.17(9), 559–572 (2017).

Do, H. T. T., Lee, C. H. & Cho, J. Chemokines and their receptors: multifaceted roles in cancer progression and potential value as cancer prognostic markers. Cancers. 12(2). (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol. Immunol.17(8), 807–821 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Radiotherapy and immunology. J. Exp. Med.221(7). (2024).

Märkl, F., Huynh, D., Endres, S. & Kobold, S. Utilizing chemokines in cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 8(8), 670–682 (2022).

Alkhatib, G. et al. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 272(5270), 1955–1958 (1996).

Pozzi, S. & Satchi-Fainaro, R. The role of CCL2/CCR2 axis in cancer and inflammation: the next frontier in nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.209, 115318 (2024).

Murphy, P. M. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol.12, 593–633 (1994).

Goldman, M. J. et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat. Biotechnol.38(6), 675–678 (2020).

Topalian, S. L., Taube, J. M. & Pardoll, D. M. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 367(6477). (2020).

Kim, S. T. et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med.24(9), 1449–1458 (2018).

Adler, E. P., Lemken, C. A., Katchen, N. S. & Kurt, R. A. A dual role for tumor-derived chemokine RANTES (CCL5). Immunol. Lett.90(2–3), 187–194 (2003).

Du, J. et al. Research progress of the chemokine/chemokine receptor axes in the oncobiology of multiple myeloma (MM). Cell. Commun. Signal.. 22(1), 177 (2024).

Marques, R. E., Guabiraba, R., Russo, R. C. & Teixeira, M. M. Targeting CCL5 in inflammation. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 17(12), 1439–1460 (2013).

Aldinucci, D., Borghese, C. & Casagrande, N. The CCL5/CCR5 axis in cancer progression. Cancers. 12(7). (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Endothelial cells enhance prostate cancer metastasis via IL-6→androgen receptor→TGF-β→MMP-9 signals. Mol. Cancer Ther.12(6), 1026–1037 (2013).

Schlecker, E. et al. Tumor-infiltrating monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells mediate CCR5-dependent recruitment of regulatory T cells favoring tumor growth. J. Immunol.189(12), 5602–5611 (2012).

Lin, K. et al. T1 contrast in the myocardium and blood pool: a quantitative assessment of gadopentetate dimeglumine and gadofosveset trisodium at 1.5 and 3 T. Invest. Radiol.49(4), 243–248 (2014).

McGuire, A., Ostertag-Hill, C. A., Aizik, G., Li, Y. & Kohane, D. S. Benzonatate as a local anesthetic. PLoS ONE. 18(4), e0284401 (2023).

Waalewijn, H. et al. First pharmacokinetic data of tenofovir alafenamide fumarate and tenofovir with dolutegravir or boosted protease inhibitors in African children: a substudy of the CHAPAS-4 trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.77(6), 875–882 (2023).

Smith, S. et al. Antiseptic skin agents to prevent surgical site infection after clean implant surgery: subgroup analysis of the NEWSkin prep trial. Surg. Infect.24(9), 818–822 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2023-BS-100).;

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJS: formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization, writing—original draft. YX: formal analysis, visualization, software, investigation. YL: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shan, J., Xu, Y. & Lun, Y. Comprehensive analysis of the potential biological significance of CCL5 in pan-cancer prognosis and immunotherapy. Sci Rep 14, 22138 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73251-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73251-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CircRNAs: functions and emerging roles in cancer and immunotherapy

BMC Medicine (2025)

-

Expression and prognosis of CXCL13 in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma based on bioinformatics analysis

Discover Oncology (2025)